Abstract

This study presents the case of a shih tzu puppy, in which a rare congenital Morgagni diaphragmatic hernia was diagnosed. The diagnosis was based on abdominal and thoracic radiographs, including a contrast study of the gastrointestinal tract, which revealed a co-existing umbilical hernia. Both hernias were repaired by surgery.

Résumé

Hernie diaphragmatique rétrosternale (de Morgagni). Cette étude présente le cas d’un chiot Shih Tzu, chez lequel une rare hernie diaphragmatique congénitale de Morgagni a été diagnostiquée. Le diagnostic s’est fondé sur des radiographies abdominales et thoraciques, incluant une étude de contraste du tractus gastrointestinal, qui a révélé une hernie ombilicale coexistante. Les deux hernies ont été réparées par chirurgie.

(Traduit par Isabelle Vallières)

A 1-month-old female shih tzu puppy was referred to the Laboratory of Radiology and Ultrasonography, Department and Clinic of Animal Surgery, University of Life Science in Lublin, Poland. The puppy was reluctant to eat without assistance, and when fed milk or a small amount of food it vomited immediately. Before the occurrence of these symptoms, the puppy had developed normally, as had the other puppies from the same litter. It was the only animal from this litter in which an umbilical hernia had developed, which had been observed by the owner 3 to 4 d after the puppy was born.

Case description

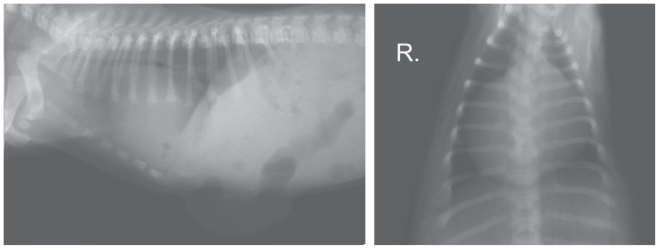

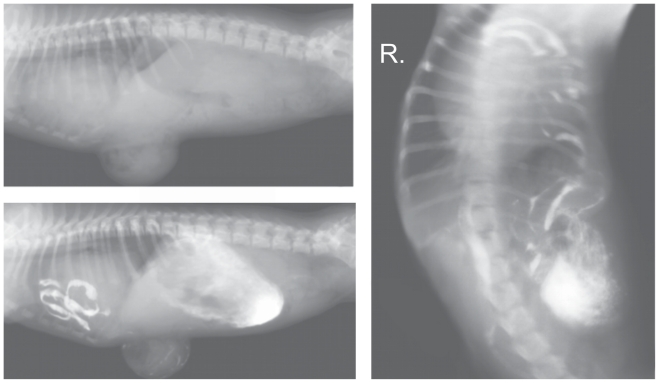

Radiographs were taken with the puppy in right lateral recumbency (Figure 1). A survey radiograph of the thorax showed a slight increase in lung opacity and narrowing of the tracheal lumen. The cardiac silhouette was considerably enlarged and rounded; it occupied 4 intercostal spaces, and its width in the dorso–ventral view at the level of the 6th and 7th ribs was almost equal to the width of the thorax. Individual small round gas shadows were visible over the cardiac silhouette, adjacent to the cardiophrenic angle. The ventral diaphragmatic surface was obscured. The abdominal radiograph showed the presence of round gas shadows of various sizes in the anterior part of the abdomen, below the liver shadow. Outside the peritoneal space below the skin surface, a gas-distended segment of intestine was observed inside a large umbilical hernia which extended caudally from the sternal xiphoid process. Close to the hernia at the level of the 7th to the 12th ribs the outline of the abdominal wall was obscured. The remaining intestinal loops were partly filled with what appeared to be semi-liquid and gas. The visceral organs remained in their normal positions.

Figure 1.

Survey radiographs of the abdominal cavity and the thorax of the puppy taken at 1 mo of age.

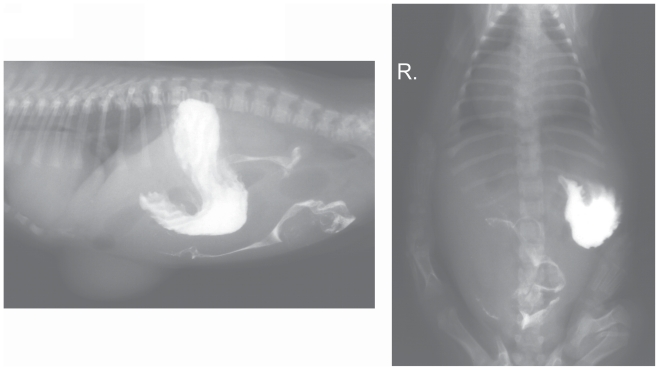

The radiographs suggested a diaphragmatic hernia. In order to confirm this diagnosis, a contrast study of the gastrointestinal tract with the use of barium sulfate suspension (1 g/mL) (Barium Sulfuricum; Medana Pharma Terpol Group S. A., Sieradz, Poland) was conducted. The contrast medium in 1:1 solution (as recommended by the producer) was administered orally at a single dose of 10 mL. Radiographs in right lateral and dorso-ventral recumbency were obtained after 30 min (Figure 2), and subsequently at 1-hour intervals (Figures 3 and 4). The contrast study showed a vertical positioning of the stomach with dislocation to the left but it did not reveal dislocation of abdominal contents into the thorax. A loop of small intestine was present within the umbilical hernia. The rest of the small intestine, together with the large intestine, was normally placed within the abdominal cavity. No gas shadows, such as those visible on the survey radiographs, were observed in the area of the cardiophrenic angle. The time for passage of the contrast medium was normal.

Figure 2.

Radiographs taken 30 min after barium administration.

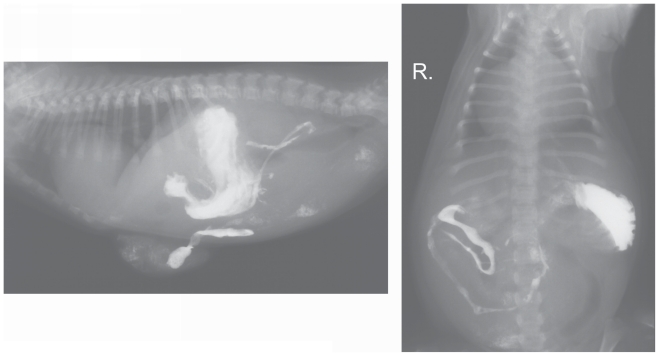

Figure 3.

Radiographs taken 2 h after barium administration.

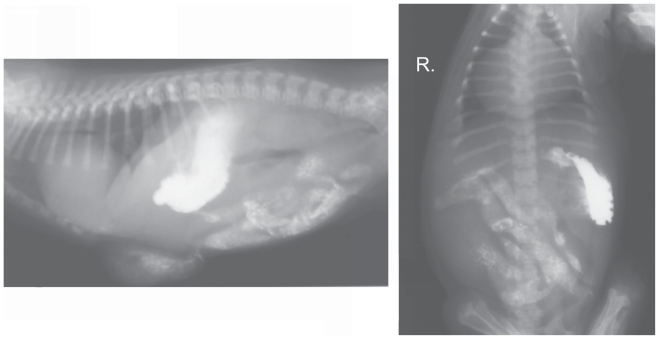

Figure 4.

Radiographs taken 3 h after barium administration.

The owner decided against the recommended surgery and the puppy was returned to the veterinary clinic in which it had been treated previously. Two months later the animal was again referred to the Laboratory of Radiology and Ultrasonography. The dog’s condition had worsened considerably during the interval. The animal did not accept any food and was much smaller than its litter mates. It was apathetic and had low exercise tolerance.

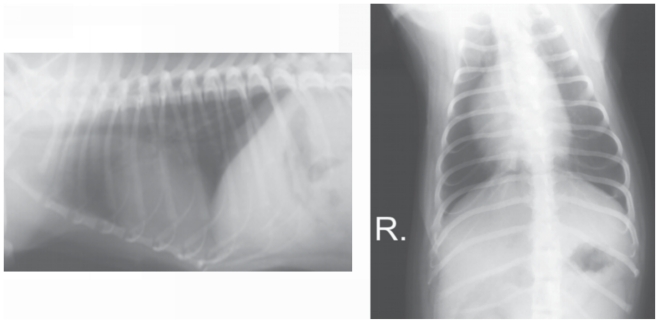

Thoracic and abdominal survey radiographs were repeated (Figure 5). An enlarged silhouette of the heart with non-homogeneous opacity extended to 6 intercostal spaces. Within the silhouette of the heart there were visible gas shadows. The thoracic diaphragmatic surface was indistinguishable ventrally. The appearance of the lungs and the trachea was similar to that of 2 mo earlier. Within the umbilical hernia there were numerous loops of small intestine. In comparison to the previous observations, the hernia was considerably enlarged due to the growth of the dog. However, its relative anatomical size had not changed and it was located at the level of the 7th to the 12th ribs on the lateral radiograph.

Figure 5.

Survey radiograph and radiographs taken 25 min after barium administration, when the dog was 3 mo old.

A contrast study was carried out by administering barium sulfate per os in a single dose of 15 mL. Lateral and dorso-ventral radiographs made after 25 min confirmed the presence of numerous loops of the small intestine in the pleural space, between the cardiac silhouette and the thoracic wall, on the left side (Figure 5). Loops of the small intestine were also found in the area of the umbilical hernia and between the liver and the considerably enlarged and abnormally located stomach, which occupied 2/3 of the peritoneal space.

After examination the animal underwent surgery to repair the diaphragmatic and umbilical hernias. Intraoperatively, in the ventral part of the diaphragm on the left side a regular opening of approximately 3 cm was found, as well as a 5-cm defect in the ventral body wall, which was continuous with the defect in the diaphragm. Small intestine was present in both the diaphragmatic hernia and the umbilical hernia. The duodenum was found within the peritoneal space.

Six months after the surgery a follow-up radiographic examination showed a normal outline of the diaphragm and an absence of abnormalities associated with the organs located in the abdomen and the thorax, except for slightly enlarged heart ventricles (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Follow-up radiographs of the thorax of the dog at 9 mo of age.

Discussion

Diaphragmatic hernias resulting from congenital defects constitute 15% of all defects in the diaphragm (1). They may occur as a consequence of failure of the pleuroperitoneal folds to fuse with other parts of the developing diaphragm (particularly the septum transversum) or as a result of an incomplete closure of the pleuroperitoneal canals on the ventral part of the diaphragm (1–4). Among the described cases there are also examples of congenital diaphragmatic hernias resulting from intrauterine fetal injury (1,2,4). The most frequent places for congenital hernias are the sterno-costal triangle (the Morgagni’s foramen, the Larrey’s space) and the lumbocostal triangle (the Bochdalek’s foramen) (5–7).

In animals, peritoneopericardial hernia is the most common type of congenital defect of the diaphragm and pericardium (2,8). Lack of separation between the peritoneal and pleural spaces results in visceral organs herniating through Morgagni’s foramen into the pericardial sac (9). Hernias through the ventral diaphragm into the pleural space are less common. This type includes the (Morgagni) retrosternal hernia. Another type is Bochdalek’s diaphragmatic hernia, in which visceral organs move through the foramen in the muscular part of the diaphragm, created in embryonic life in the sternocostal triangle (7,10). In most cases the herniated viscera are located within a hernial sac in the pleural space, surrounded by parietal diaphragmatic pleura and sometimes by peritoneum. This type of hernia, due to the presence of the hernial sac, is called a true hernia (4,11). In addition to hernias of the ventral diaphragm, a second group of congenital diaphragmatic hernias consists of esophageal hiatal hernias and sliding perivascular hernias (of the opening of the aorta and the jejunal vein on the side of the cauda) (2,3,11).

This paper presents the case of a Morgagni retrosternal hernia, which is rarely reported in the veterinary literature. It is classified in the group of true diaphragmatic hernias (3,12,13). Clinical signs of the hernia vary widely. Cases of postnatal death have been described (5,14), but clinical signs may be mild or absent altogether, or may develop over a relatively long period. Diaphragmatic defects resulting from developmental disorders can be so small that they never result in hernia (1). Where clinical signs are present, their intensity depends on the size of the diaphragmatic defect and the type and volume of herniated organs (4,9). A sudden increase in intra-abdominal pressure, adipose tissue deposits within the peritoneal cavity, or later occurrence of trauma may result in dislocation of intestines into the thorax, and then the occurrence of various clinical symptoms characteristic of a traumatic diaphragmatic hernia: dyspnea, abdominal pain, vomiting, regurgitation, muffled cardiac sound, and weakened pulse (1,4,6).

Absence of pathognomonic signs of Morgagni retrosternal hernia hinders diagnosis, which is often accidental and is based mainly on thoracic and abdominal radiographs. In order to determine which organs have been herniated, a contrast study of the gastrointestinal tract and an ultrasonographic examination are recommended (1,6). The ultrasonographic examination is particularly useful in cases in which parenchymal organs herniate into the thorax. In radiographs these organs have a homogenous opacity, which hinders diagnosis; therefore, they should be differentiated from mass lesions (1,12,15). Ultrasound examination should be conducted if survey radiographs show local outline loss of the diaphragmatic surface (1,15,16). In order to detect small defects of the diaphragm, it is crucial to use positive contrast peritoneography, which may reveal passage of the contrast medium from the peritoneal cavity into the pleural cavity (1,2,17). Both these latter methods may produce false negative results, if diaphragmatic defects have been blocked by visceral organs (2,16). In order to reach a definitive diagnosis, computed tomography (CT) scanning may be necessary. Contrast media and magnetic resonance are commonly applied to locate the hernial ring and to determine its size, as well as to evaluate the hernial sac and its location against the diaphragm (6,18). Other methods of imaging diagnostics, such as selective angiography, pneumoperitoneography and pleurography, are mentioned in the literature (2,3,19).

In the present case, nonspecific clinical symptoms in the form of regurgitation and vomiting occurred, but did not suggest a diaphragmatic hernia. It was not the occurrence of clinical symptoms characteristic of other disease entities that caused a diagnostic problem but rather difficulties with the initial interpretation of the radiographs. A survey radiograph of the 1-month-old puppy could suggest the occurrence of diaphragmatic hernia; however, this diagnosis was not confirmed by a contrast study of the gastrointestinal tract. Gas shadows initially seen associated with the diaphragm did not appear on subsequent radiographs. The presence of the large umbilical hernia also hindered the diagnosis. Intestinal loops within the hernial sac were located cranioventrally from the liver, close to the cardiophrenic angle, which may have partly obscured the image of the diaphragm on the radiograph. The presence of the diaphragmatic hernia with numerous intestinal loops of the small intestine in the pleural space was not confirmed until the next radiographic study carried out 2 mo later. It represents a gradual dislocation of visceral organs to the thorax, which may have been triggered by short incidents of increased intra-abdominal pressure, possibly as a result of recurring vomition. In this case, within the period between the 2 examinations, no injuries that could have contributed to the hernia’s development were observed.

A follow-up examination carried out 6 mo after the surgery did not reveal any changes in location of organs in the abdominal cavity and in the thorax. The diaphragmatic outline was normal and there were no irregularities of lung tissue. One theory of the pathogenesis of congenital diaphragmatic hernias suggests that they may be caused by slower development of the primordium and lung hypoplasia on the left side. However, in the present case, the increase in lung opacity visible during previous examinations was probably caused by pressure on the caudal lobes by organs herniated into the thorax, manifested clinically only by reduced exercise tolerance.

Congenital diaphragmatic hernias are described as co-existing with other developmental disorders, including umbilical hernias, which often result from an abnormal fusion of the umbilical ring and the linea alba (2,4,20). The typical location of displaced organs within the sternocostal triangle on the left side, along with the occurrence of the umbilical hernia itself, and the appearance of clinical signs shortly after birth, firmly indicate that the disease is congenital (2). The dog has not developed any clinical signs related to the gastrointestinal and respiratory tracts, or any health problems, in the 2 y since the surgical correction of her hernia.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. Janusz Karpinski and Dr. Wieslaw Janiszewski, who carried out surgery on the puppy and made data available for inclusion in this publication. CVJ

Footnotes

Use of this article is limited to a single copy for personal study. Anyone interested in obtaining reprints should contact the CVMA office (hbroughton@cvma-acmv.org) for additional copies or permission to use this material elsewhere.

References

- 1.Park RD. The Diaphragm. In: Thrall DE, editor. Textbook of Veterinary Diagnostic Radiology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders Company; 1998. pp. 294–307. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Suter PF. A Text Atlas of Thoracic Diseases of the Dog and Cat. 1st ed. Wettswil: 1984. Thoracic Radiography; pp. 179–203. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Auger JM, Riley SM. Combined hiatal and pleuroperitoneal hernia in a shar–pei. Can Vet J. 1997;38:640–642. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kelmer G, Kramer J, Wilson DA. Diaphragmatic hernia: Etiology, clinical presentation, and diagnosis. Compend Cont Ed Equine Edition. 2008;3:28–35. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dillon E, Renwick M, Wright C. Congenital diaphragmatic herniation: Antenatal detection and outcome. Br J Radiol. 2000;73:360–365. doi: 10.1259/bjr.73.868.10844860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Minneci PC, Deans KJ, Kim P, Mathisen DJ. Foramen of Morgagni hernia: Changes in diagnosis and treatment. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;77:1956–1959. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2003.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ubee SS, Gokul K, Artioukh DY. Congenital malformation of the diaphragm and left colon: Strangulated Bochdalek hernia in an adult. Surgical Practice. 2009;13:24–25. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Statz GD, Moore KE, Murtaugh RJ. Surgical repair of a peritoneopericardial diaphragmatic hernia in a pregnant dog. J Vet Emerg Crit Care. 2007;17:77–85. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ozer K, Guzel O, Devecioglu Y, Aksou O. Diaphragmatic hernia in cats: 44 cases. Medycyna Wet. 2007;63:1564–1567. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rahal SC, Mamprim MJ, Muniz LMR, Teixeira CR. Type–4 esophageal hiatal hernia in a Chinese shar–pei dog. Vet Radiol Ultrasound. 2003;44:646–647. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-8261.2003.tb00524.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim ES, Kang JY, Pyo CH, Jeon EY. A Morgagni diaphragmatic hernia found after removal of mediastinal tumor. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2008;14:175–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spuzak J, Kubiak K, Jankowski M, Dubinski B, Nicpon J, Sikorska A. Zastosowanie endoskopii w rozpoznawaniu przepukliny wslizgowej rozworu przelykowego u psow. Medycyna Wet. 2008;64:684–685. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Voges AK, Bertrand S, Hill RC, Neuwirth L, Schaer M. True diaphragmatic hernia in a cat. Vet Radiol Ultrasound. 1997;38:116–119. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-8261.1997.tb00825.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stevenson DE. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia in beagle pups. J Small Anim Pract. 1963;4:339–340. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Debiak P, Lojszczyk – Szczepaniak A, Komsta R. Diagnostics of canine peritoneal — pericardial diaphragmatic hernia (PPDH) Medycyna Wet. 2009;65:181–183. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spattini G, Rossi F, Vignoli M, Lamb CR. Use of ultrasound to diagnose diaphragmatic rupture in dogs and cats. Vet Rad Ultrasound. 2003;44:226–230. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-8261.2003.tb01276.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Choi J, Kim H, Kim M, Yoon J. Imaging diagnosis — Positive contrast peritoneographic features of true diaphragmatic hernia. Vet Rad Ultrasound. 2009;50:185–187. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-8261.2009.01514.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dancewicz M, Kowalewski J, Pepilinski J. Przepuklina przeponowa Morgagniego — trudny problem diagnostyczny. Pol Merk Lek. 2006;121:90–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koper S, Mucha M, Silmanowicz P, Karpinski J, Zilo T. Selective abdominal angiography as a diagnostic method for diaphragmatic hernia in the dog: An experimental study. Vet Radiol Ultrasound. 1982;23:50–55. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lew M, Jalynski M, Kasprowicz A, Brzeski W. Leczenie przepuklin brzusznych, zewnetrznych z zastosowaniem siatki chirurgicznej u psow. Medycyna Wet. 2006;62:1148–1151. [Google Scholar]