Abstract

A functional simulation of hearing loss was evaluated in its ability to reproduce the temporal modulation transfer functions (TMTFs) for nine listeners with mild to profound sensorineural hearing loss. Each hearing loss was simulated in a group of three age-matched normal-hearing listeners through spectrally shaped masking noise or a combination of masking noise and multiband expansion. TMTFs were measured for both groups of listeners using a broadband noise carrier as a function of modulation rate in the range 2 to 1024 Hz. The TMTFs were fit with a lowpass filter function that provided estimates of overall modulation-depth sensitivity and modulation cutoff frequency. Although the simulations were capable of accurately reproducing the threshold elevations of the hearing-impaired listeners, they were not successful in reproducing the TMTFs. On average, the simulations resulted in lower sensitivity and higher cutoff frequency than were observed in the TMTFs of the hearing-impaired listeners. Discrepancies in performance between listeners with real and simulated hearing loss are possibly related to inaccuracies in the simulation of recruitment.

INTRODUCTION

The functional simulation of sensorineural hearing impairment is an important research tool that can help to elucidate the nature of hearing impairments and suggest or eliminate compensatory signal-processing schemes. In such a simulation, the sound that reaches the ear of the normal-hearing (NH) listener is transformed to achieve specific changes in auditory abilities that mimic those experienced by listeners with real hearing impairment. A successful hearing-loss simulation should be capable of reproducing in NH listeners the performance of hearing-impaired (HI) listeners on a wide range of psychoacoustic and speech-reception tasks. The current study assessed the validity of a particular hearing-loss simulation technique (Desloge et al., 2010) for reproducing the modulation-detection performance observed in hearing-impaired listeners by normal-hearing listeners with simulated hearing loss.

Several approaches to hearing-loss simulation have been used in studies of the psychoacoustic and speech-reception abilities of HI listeners. One class of approaches is concerned with simulating aspects of cochlear hearing loss related to audibility. Additive masking noise (e.g., Milner et al., 1984; Zurek and Delhorne, 1987; Florentine et al., 1988; Dubno and Schaefer, 1992; Florentine et al., 1993) has been used to reproduce the elevated thresholds, reduction in dynamic range, and loudness recruitment observed in sensorineural hearing loss. With an additive-noise simulation, signals can be delivered to listeners with real and simulated hearing loss at equivalent levels expressed both as sound-pressure level (SPL) and sensation level (SL). Because of the levels of required masking noise, however, this simulation technique is limited to losses less than roughly 70 dB hearing level (HL). Another technique, known as multiband amplitude expansion (Villchur, 1973,1974; Duchnowski, 1989; Moore and Glasberg, 1993; Duchnowski and Zurek, 1995; Graf, 1997; Lum and Braida, 1997), employs level-dependent attenuation of the input signal to achieve elevated thresholds and recruitment. This method can thus be used to simulate impairments that are more severe than those that can be comfortably simulated using masking noise. A second class of approaches to hearing-loss simulation has focused on the reproduction of various aspects of the suprathreshold consequences of sensorineural loss and has examined these effects in isolation or in combination with each other. For example, the reduced frequency selectivity observed in HI listeners has been simulated through spectral smearing of signals applied to NH listeners and has been studied by itself (Baer and Moore, 1993) or in combination with a multiband expansion (MBE) simulation of loudness recruitment (Moore et al., 1995; Nejime and Moore, 1997; Moore et al., 1997).

Previous research concerned with simulating aspects of temporal processing in sensorineural hearing loss has been conducted using simulations based on additive-noise or multiband expansion (see review by Reed et al., 2009). These studies indicate that the performance of HI listeners can be well reproduced in some temporal tasks such as gap detection (Florentine and Buus, 1984; Glasberg and Moore, 1992; Moore et al., 2001), gap-duration discrimination (Buss et al., 1998), and the detection of brief tones in modulated noise (Humes, 1990), but not in others such as temporal integration in tonal detection (Florentine et al., 1988) and the detection of tones as a function of the phase curvature of a harmonic masker (Oxenham and Dau, 2004).

The current study examined the degree to which a hearing-loss simulation based on the use of additive noise and MBE is capable of reproducing the temporal modulation transfer functions (TMTFs) of HI listeners with broadband noise carriers. The TMTF assesses temporal-processing ability through measurement of the minimal amount of sinusoidal amplitude modulation (SAM) necessary for discriminating between modulated and unmodulated carriers as a function of the frequency of modulation (Viemeister, 1979).1 Such temporal fluctuations in the amplitude envelopes of speech signals have been shown to provide cues to properties such as fundamental frequency, voicing, and manner of consonant production (e.g., Van Tasell et al., 1987; Shannon et al., 1995; Turner et al., 1995). Further, it has been proposed (e.g., Festen and Plomp, 1990) that difficulties experienced by HI persons when listening to speech in noise may be related to deficits in temporal processing.

The TMTF has been hypothesized to be linked to speech reception in temporally fluctuating noise (e.g., Takahashi and Bacon, 1992). Previous studies have demonstrated that the release from masking enjoyed by NH listeners in temporally fluctuating compared to continuous background noise is often reduced for HI listeners (Shapiro et al., 1972; Festen and Plomp, 1990; Bacon et al., 1998; Peters et al., 1998; Summers and Molis, 1994; Eisenberg et al., 1995; George et al., 2006; Lorenzi et al., 2006; Bernstein and Grant, 2009; Desloge et al., 2010). Takahashi and Bacon (1992) have hypothesized that the ability to follow the modulations in temporally varying interference (and thus take advantage of the improved speech-to-interference ratios during gaps in the interference) may be related to the ability to detect the modulation of a sinusoidally modulated noise as a function of the frequency of modulation. Takahashi and Bacon (1992), however, did not find correlations between modulation-detection ability and either masking release or age in a study employing young normal-hearing listeners and elderly listeners with normal hearing or mild cochlear loss. It is nonetheless possible that correlations between the TMTF and masking release may be observed in listeners with greater degrees of hearing impairment and thus a greater range of performance on both these measures.

The current study employed a hearing-loss simulation based on a combination of additive noise masking and multiband expansion. This approach to hearing-loss simulation permits the specification of frequency-dependent threshold elevations associated with a given hearing loss as well as effects of loudness recruitment and allows consideration of losses in excess of 70 dB HL. Furthermore, the simulation permits signals to be presented at roughly equivalent sensation and loudness levels for HI and NH listeners. The effects of age were also controlled by testing NH listeners with simulated hearing loss who were matched roughly in age to each individual HI listener.

Previous studies of the TMTF for HI listeners have typically compared their performance to that of NH listeners for carrier stimuli presented at equal SPL (Bacon and Viemeister, 1985; Moore and Glasberg, 2001; Moore et al., 1992; Bacon and Gleitman, 1992; Grant et al., 1998), equal SL (Lamore et al., 1984; Moore et al., 2001; Moore et al., 1992; Bacon and Gleitman, 1992), or equal loudness (Formby, 1987). For NH listeners, detection of SAM in a broadband-noise carrier (expressed as the threshold value of modulation depth in dB) is relatively constant over a wide range of overall levels. The modulation threshold is constant at roughly −25 dB for modulation rates in the range 2 to 10 Hz, increases by roughly 3 dB at 50 Hz, and then increases at a rate of roughly 4 dB∕oct in the range 50 to 1000 Hz (Viemeister, 1979; Bacon and Viemeister, 1985; Bacon and Gleitman, 1992). Typically, the shape of the TMTF is similar between NH and HI listeners with some reported differences in sensitivity, including cases of both higher and lower sensitivity for HI than for NH listeners (Bacon and Viemeister, 1985; Bacon and Gleitman, 1992; Moore et al., 1992). A more rapid deterioration in the performance of HI than NH listeners with an increase in modulation frequency has also been observed (Bacon and Viemeister, 1985; Formby, 1987; Lamore et al., 1984; Grant et al., 1998). Bacon and Viemeister (1985) simulated the effects of reduced bandwidth in listeners with high-frequency hearing impairment through the use of lowpass-filtered noise signals. Results for NH listeners in the lowpass condition simulated both the decreased overall sensitivity and the reduction in the lowpass cutoff frequency observed for the TMTF curves of the HI listeners than for NH listeners in the broadband condition. Even at equal SLs, modulation thresholds were roughly 5 dB higher for the lowpass than for the broadband condition. These authors thus concluded that reduced bandwidth may be responsible for the decreased TMTF sensitivity observed for some HI listeners.

In addition to examining the ability of the hearing-loss simulation to reproduce the TMTFs of HI listeners, the current research was also concerned with relating the TMTF to speech reception in temporally fluctuating background noise. In a previous study employing the same hearing-loss simulations, Desloge et al. (2010) measured speech-reception thresholds for 50%-correct intelligibility of sentences in continuous and fluctuating background noise for listeners with real and simulated hearing impairment. In general, the simulation was capable of reproducing the performance of the HI listeners in both types of noise. The magnitude of the masking release (i.e., S∕N in dB for reception of sentences in continuous noise minus S∕N for interrupted noise) for the HI listeners was generally less than that observed in NH listeners, but was well-reproduced by the simulations.

In the present study, the TMTF was measured for listeners with mild-to-profound sensorineural loss of various configurations. For each individual HI listener, three age-matched NH listeners completed the same task while listening to stimuli processed through a simulation of hearing loss that used a combination of threshold-elevating masking noise and multiband expansion. The TMTFs obtained for listeners with real and simulated hearing impairment were compared statistically and through use of a simple lowpass-filter model (Bacon and Gleitman, 1992) to estimate the maximal sensitivity and time constants of the functions. Performance on the TMTF task was then related to previous measurements of speech reception in a temporally fluctuating background noise reported by Desloge et al. (2010) using the same set of HI and NH listeners and the same hearing-loss simulations.

METHODS

Hearing-loss simulation techniques

In the current study, hearing loss was simulated initially using additive threshold noise (TN) that was spectrally shaped to yield the desired threshold shifts. For severe threshold shifts (> 60–70 dB HL), however, the required amount of threshold noise could be unacceptably loud (i.e., > 80 dB SPL). In these cases, TN was combined with multiband expansion (MBE) to produce the desired threshold shifts. Each of these methods (TN and TN∕MBE) is described below.

Simulation using additive threshold noise (TN)

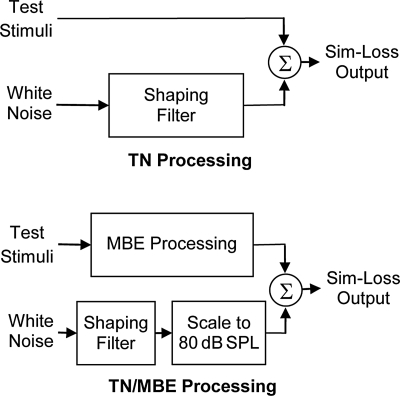

For this hearing-loss simulation technique, the desired frequency-dependent threshold shifts were obtained using shaped threshold noise that was added to each stimulus prior to listener presentation (see top panel of Fig. 1). The specific frequency-dependent noise necessary to simulate a particular hearing loss was derived as follows. The desired hearing thresholds were specified in terms of dB SPL at a minimum of six audiometric frequencies including 250, 500, 1000, 2000, 4000, and 8000 Hz. If necessary, the lowest and highest measured thresholds were extended so that the threshold specification covered frequencies ranging from 80 Hz to 12,500 Hz. Linear interpolation (in the log-frequency versus dB-SPL domain) was then used to estimate thresholds at all third-octave-band center frequencies within this range. The spectrum level of the threshold-shifting noise, SpecLev(f1∕3-oct), was calculated at each third-octave frequency by subtracting the critical ratio, CR(f1∕3-oct) (Hawkins and Stevens, 1950), which establishes the minimal signal-to-noise ratio at which a particular tone can be heard, from the desired threshold, THR(f1∕3-oct):

| (1) |

The CR values employed in these computations were 17.75, 16.3, 17.25, 18.5, 19.25, 20.5, 22.5, 25.1, 26, and 27 dB at 125, 250, 500, 1000, 1500, 2000, 3000, 4000, 6000, and 8000 Hz, respectively. These CR values were extended and linearly interpolated (in the log-frequency versus dB domain) to cover the third-octave-band frequencies ranging from 80 to 12,500 Hz. Finally, these spectrum levels were used to determine the magnitude response of the filter required to transform white noise into additive threshold noise that yielded the threshold shift associated with the simulated loss. This magnitude response was inverse-Fourier-transformed and Hanning-windowed to yield a 128-ms-duration finite-impulse-response shaping filter (indicated in the top panel of Fig. 1) that was used to create the actual TN in the experiment.

Figure 1.

Panel on top: Block diagram of system used for hearing-loss simulation based on additive threshold noise. Panel on bottom: Block diagram of system used for hearing-loss simulation based on a combination of additive threshold noise and multiband expansion (MBE) processing. The upper path processes the signal with MBE level-dependent gain while the lower path generates the threshold-shifting noise.

Because of the matching threshold shift, the test stimuli were presented to HI and simulated-loss NH listeners at the same sound pressure level (SPL) and sensation level (SL). Further, because the additive threshold noise produces a growth of loudness similar to that experienced by HI listeners with the same threshold shift (e.g., Steinberg and Gardner, 1937), this method of simulating hearing loss simulated loudness recruitment as well.

Simulation using additive threshold noise and multiband expansion (TN∕MBE)

Multiband expansion (MBE) produced threshold shifts by attenuating the stimulus dynamically. This process involved passing the signal through a multiband filterbank, monitoring short-time band signal levels, and applying a level-dependent attenuation to each band signal (Duchnowski, 1989; Duchnowski and Zurek, 1995; Graf, 1997; Lum and Braida, 1997; Moore and Glasberg, 1993). The level-dependent attenuation used for hearing loss simulation was designed to yield the desired threshold shift as well as the loudness growth associated with sensorineural hearing loss. Specifically, MBE applied band attenuations that translated an input signal at the level of the simulated threshold so that it was presented at the listener’s actual hearing threshold. The degree of attenuation then decreased as input level increased above the simulated threshold until full recruitment was reached and the attenuation was equal to 0 dB. For input levels above the full recruitment level, no attenuation was used.

TN and MBE were combined (bottom panel of Fig. 1) in the following manner to produce a desired threshold shift. First, the wideband level, TNlev, of the threshold noise required to yield a TN-only simulation of the desired loss was calculated. TN∕MBE simulation was adopted only when TNlev exceeded 80 dB SPL. In this case, the TN was attenuated by a factor of

| (2) |

to yield a scaled TN with a wideband level of exactly 80 dB SPL. Given that the unscaled TN was designed to produce the desired threshold shifts of THR(f), the attenuated noise then yielded threshold shifts of up to α dB below the desired threshold shifts but not lower than the normal-hearing threshold of 0 dB SL:

| (3) |

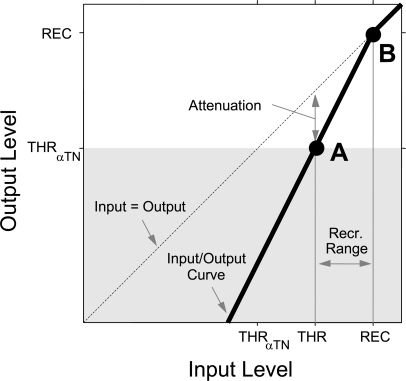

MBE was then used to recreate the remaining threshold shift necessary to restore the simulated thresholds to the desired levels. Figure 2 illustrates how the scaled TN and MBE were combined to yield the complete desired threshold shift in a particular frequency band. The solid line shows the mapping between input and output level. The MBE attenuation is equal to the vertical difference between this input∕output mapping curve and the input-equals-output curve shown in the plot. At point A, the mapping attenuates inputs at a desired threshold of THR so that the corresponding output level is exactly equal to THRαTN, i.e., the hearing threshold in the presence of the scaled threshold noise. The MBE attenuation then decreases as input level increases until the level of full recruitment (REC) is reached at point B and no MBE attenuation occurs. In this way, MBE attenuates input sound levels that are below THR into output sound levels that are below THRαTN and that are inaudible in the presence of the scaled-down threshold noise. MBE output levels corresponding to input levels above REC are not attenuated. For the current research, the full-recruitment level REC was always fixed at 100 dB HL.

Figure 2.

Example MBE input∕output level mapping curve used to demonstrate how MBE processing is combined with TN processing to yield the TN∕MBE method of hearing-loss simulation.

The specific MBE implementation used in this research was based upon the work of Moore and Glasberg (1993). The input signal was first divided into 13 frequency bands using a fourth-order gammatone filterbank with center frequencies ranging from 100 to 5837 Hz and bandwidths in the range 106.5 to 1964 Hz. The bandpass filter impulse responses were time-aligned so that all impulse response peaks were coincident. The Hilbert transform was computed and used to separate each band signal into an envelope (Hilbert-transform-output magnitude lowpass filtered at 100 Hz) and fine-structure (Hilbert-transform output divided by the Hilbert-transform-output magnitude) components. The input envelopes in each band were converted into output envelopes via the MBE input-to-output mapping described above. The output envelopes were combined with the input fine-structure and the inverse Hilbert transform was applied to obtain output band signals. Finally, the output band signals were summed to form the output signal.

As shown in the block diagram (bottom panel of Fig. 1), the input signal (upper path) was modified via MBE processing and added to spectrally shaped noise (lower path), which, as stated above, was scaled to a level of 80 dB SPL, for presentation to the listener. The scaling term α from Eq. 2 defines the relative contributions of TN and MBE to the combined TN∕MBE simulation. Specifically, the threshold shifts obtained with the scaled TN, THRαTN(f), were up to α dB lower than the desired threshold shift. This gap was then recovered using MBE processing.

Relative to the HI listeners, simulated-loss NH listeners using a TN∕MBE simulation experienced stimuli at the equivalent SL but at a lower SPL, of up to α dB.

Stimulus generation

Experiments were controlled by a PC equipped with a high-quality, 24-bit PCI sound card (either LynxOne by LynxStudios or E-MU 0404 by Creative Professional). Stimulus signals (including the hearing-loss simulation, if present) were: generated and played out using MATLAB™; passed through a pair of Tucker–Davis (TDT) PA4 programmable attenuators and a TDT HB6 stereo headphone buffer; and presented to the listener in a soundproof booth via a pair of Sennheiser HD580 headphones. The system was calibrated to compensate for the HD580 frequency response over the range of 80 Hz to 12,500 Hz so that precise sound levels could be presented as measured at the eardrums of a KEMAR manikin. Peak output levels of approximately 117 dB SPL were attainable with this system.2

The experimental stimuli were generated and adaptively modified using the AFC software package for MATLAB™ provided by Stephan Ewert and developed at the University of Oldenburg, Germany. A monitor, keyboard, and mouse located within the sound-treated booth allowed interaction with the control PC.

Listeners

Listeners with hearing impairment

Nine listeners with bilateral sensorineural hearing loss who were native speakers of American English participated in the study. Each listener was required to have had a recent clinical audiological examination (within one year of entry into the laboratory study) to verify that the hearing loss was of cochlear origin on the basis of air- and bone-conduction audiometry, tympanometry, speech-reception thresholds, and word-discrimination scores. On the listener’s first visit to the laboratory, informed consent was obtained and an audiogram was readministered for comparison with the listener’s most recent evaluation from an outside clinic. In all cases, good correspondence was obtained between these two audiograms.

These nine HI listeners are a subset of the ten listeners who participated in the study of Desloge et al. (2010). Specifically, listener HI-5 from the previous study did not participate in the current study. For continuity with the previous paper, the original labels HI-1 through HI-10 were preserved for the current study. Information on the nine HI listeners is provided in Table TABLE I., which contains data on sex, test ear, hearing-aid use, history∕etiology, age, method used to simulate hearing loss, and, for TN∕MBE simulations only, the α term [Eq. 2] that represents the maximum attenuation provided by the MBE. The listeners (who ranged in age from 21 to 69 years) were selected to have bilateral losses that were roughly symmetrical. The audiometric thresholds of the nine listeners are provided in Table TABLE I. of Desloge et al. (2010) and are consistent with laboratory-based measurements of their absolute-detection thresholds (described in Sec. 2D below and reported in Sec. 3A and Fig. 3).

Table 1.

Description of hearing-impaired subjects in terms of sex, test ear, hearing-aid (HA) use, history∕etiology, and age in years. Also provided are the mean ages of the AM-SIM group, the method used to simulate the hearing loss, and the α factor for the TN∕MBE simulations.

| Listener | Sex | Test ear | HA use in test ear? | Etiology | Age | AM-SIM group age | Sim. method | α term for TN∕MBE (dB) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HI-1 | M | L | No | Hereditary | 24 | 23.0 | TN | |

| HI-2 | M | R | Yes | Congenital? | 21 | 20.3 | TN | |

| HI-3 | M | R | No | Unknown∕adult-onset | 64 | 61.7 | TN∕MBE | 4 |

| HI-4 | F | L | Yes | Congenital | 59 | 53.0 | TN∕MBE | 7 |

| HI-6 | F | L | Yes | Unknown | 55 | 55.3 | TN | |

| HI-7 | M | R | Yes | Hereditary∕congenital | 69 | 61.3 | TN∕MBE | 13 |

| HI-8 | M | R | Yes | Hereditary | 68 | 64.0 | TN∕MBE | 10 |

| HI-9 | F | R | Yes | Congenital | 21 | 22.0 | TN∕MBE | 30 |

| HI-10 | F | L | Yes | Congenital | 43 | 44.7 | TN∕MBE | 26 |

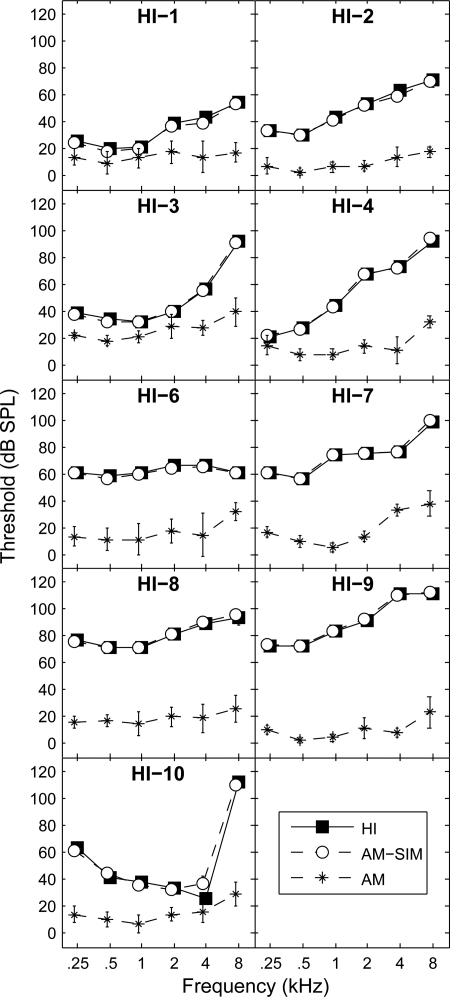

Figure 3.

Threshold in dB SPL as a function of frequency. In each subplot, absolute thresholds are shown for a given HI listener (solid squares). For each HI listener, simulated-loss thresholds are averaged across the three NH listeners in the AM-SIM group (unfilled circles). Also shown are average quiet (without simulated loss) thresholds for the AM-SIM group (asterisks).

Audiometric thresholds across ears were within 20 dB of each other at each test frequency in all but two listeners. For HI-6, this symmetry criterion was relaxed at 8000 Hz. For HI-9, thresholds for the left ear were 30–35 dB greater than those in the right ear for frequencies between 250 and 2000 Hz (and left-ear thresholds were above the limits of the audiometer at frequencies greater than 2000 Hz). For each listener, a test ear was selected for monaural listening in the experiments (shown in Table TABLE I.). Typically, this was the ear with better average thresholds across test frequencies. Hearing losses ranged from mild∕moderate to severe∕profound across listeners. The audiometric configurations observed across the hearing losses of these listeners included: (i) sloping high-frequency loss (HI-1, HI-2, HI-3, HI-4), (ii) relatively flat loss with no more than a 20-dB difference between adjacent audiometric frequencies (HI-6, HI-7, HI-8), (iii) severe low-frequency loss advancing to profound high-frequency loss (HI-9), and (iv) inverted “cookie-bite” loss characterized by near-normal thresholds in the mid-frequency range and moderate loss at low and high frequencies (HI-10). All but two of the listeners (HI-1 and HI-3) were regular or occasional hearing-aid users at the time of entry into the study.

Listeners with normal hearing

Twenty-seven NH listeners3 who were native speakers of English were recruited to participate in the hearing-loss simulation component of the study. Listeners provided informed consent and a clinical audiogram was then obtained to screen for normal hearing in at least one ear, defined as 25 dB HL or better at frequencies in the range 250 to 4000 Hz and 30 dB HL at 8000 Hz. Listeners ranged in age from 18 to 65 years and were selected as age-matched controls to each of the nine HI listeners. These listeners’ ages were in the range plus or minus 9 years relative to that of the HI listener to whom they were assigned. The mean age of the three age-matched listeners with hearing-loss simulation (referred to as the “AM-SIM” group) associated with each HI listener is provided in Table TABLE I..

For each NH listener, a test ear was selected for conducting the hearing-loss simulation testing. This was typically the same ear as that of the HI listener whose loss was being simulated. In cases where only one ear of a given listener met the audiometric criteria defined above, that ear was selected as the test ear regardless of whether or not it was the same ear as that tested for the HI listener being simulated.

A subset of five of these AM-SIM listeners also participated in the experiment without the use of hearing-loss simulation. These listeners (referred to as the “NH” group) ranged in age from 47 to 60 years with a mean age of 54 yr.

All listeners, both HI and NH, were paid for their participation in the study.

Absolute threshold and simulated-loss threshold testing

Conditions

Measurements of absolute-detection thresholds for pure tones were obtained for the test ear of each HI and NH listener without simulated hearing impairment at frequencies of 250, 500, 1000, 2000, 4000, and 8000 Hz. Thresholds at these frequencies were also measured for the NH listeners in the presence of simulated hearing impairment designed to duplicate the threshold shifts of the corresponding HI listener.

Procedure

Threshold measurements were obtained using a three-interval, three-alternative, adaptive forced-choice procedure with trial-by-trial correct-answer feedback. Tones were presented with equal a priori probability in one of the three intervals and the listener’s task was to identify the interval containing the tone. Each interval was cued on the visual display during its 500-ms presentation period with a 500-ms interstimulus interval. Tones were windowed to have a 500- ms total duration with a 10-ms Hanning-window ramp on and off (yielding a 480-ms steady-state portion). During the experimental run, the level of the tone was adjusted adaptively using a one-up, two-down rule to estimate the stimulus level required for 70.7% correct (Levitt, 1971). The step size was 8 dB for the first two reversals, 4 dB for the next two reversals, and 2 dB for the remaining six reversals. The final threshold estimate was the mean presentation level at the final six reversals. Listeners had unlimited response time and were provided with visual trial-by-trial feedback following each response.

When measuring thresholds for NH listeners with simulated hearing loss, each stimulus was processed by the hearing loss simulation immediately preceding each presentation. In both cases, the threshold-elevating noise was initiated 500 ms before the first stimulus interval and terminated 50 ms after the final interval, for a total noise-onset time of 3050 ms per trial.

Thresholds were measured in blocks of 12 runs, with each block consisting of two 6-run sub-blocks where each sub-block measured the 6 test frequencies in random order. The HI listeners typically completed two blocks of runs measuring thresholds in quiet. Each NH listener completed two blocks of runs measuring thresholds in quiet and another two blocks of runs measuring thresholds under the hearing-loss simulation. Thresholds were averaged across the two runs at each frequency under each type of listening condition.

TMTF testing

Conditions

TMTFs for broadband noise were measured in the designated test ear for all listeners using sinusoidal amplitude modulation at frequencies of 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64, 128, 256, 512, and 1024 Hz.

Procedure

The TMTF for a specific modulation frequency was estimated using a three-interval, three-alternative, adaptive forced-choice procedure with trial-by-trial correct-answer feedback. Each interval was cued on the visual display during its 500-ms duration and intervals were separated by a 500-ms interstimulus interval. On each trial, each interval contained a signal that was based on a 500-ms white noise pulse with a 10-ms Hanning-window onset and offset ramp, yielding a 480-ms steady-state portion. The white noise was band-limited to a maximum frequency of 10,000 Hz using a digital lowpass filter with a stop-band that was attenuated by 60 dB at 10,020 Hz. One of the three interval stimuli, selected at random with equal a priori probability, was further modified through the application of a 500-ms SAM window to the noise pulse. Specifically, the modulation window, W(t), consisted of a raised sine wave described by

| (4) |

where fm was the modulation frequency, Am was the modulation depth, and c was the multiplicative compensation factor of 1∕(1+Am2∕2)0.5 that was necessary to give the modulated pulses an overall level equal to that of the unmodulated pulses (Viemeister, 1979). The modulation depth Am ranged from 0.0 ( = −∞ dB) to 1.0 ( = 0 dB). In terms of the overall envelope, Am = 0.0 corresponded to a flat, “no modulation” envelope equal to the compensation term c, while Am = 1.0 corresponded to a “full modulation” envelope that cycled from 0.0 to 2.0c in value. For example, a modulation depth of −20 dB corresponded to Am = 0.1, in which case W(t) cycled from 0.9c to 1.1c, where c = 0.9975.

All three noise pulses (two without modulation and one with modulation) were scaled for presentation at a level that was chosen for each HI listener and his or her corresponding AM-SIM group. The level was whichever was greater of either 70 dB SPL or the level derived from setting the spectrum level of the broadband noise at 10 dB above the listener’s minimum hearing threshold level across the six pure-tone test frequencies up to a maximum presentation level of 100 dB SPL. The levels employed for each HI listener and the corresponding AM-SIM group are indicated together with the results in Fig. 5 below. For the AM-SIM groups, the TN was played continuously throughout the duration of each trial.

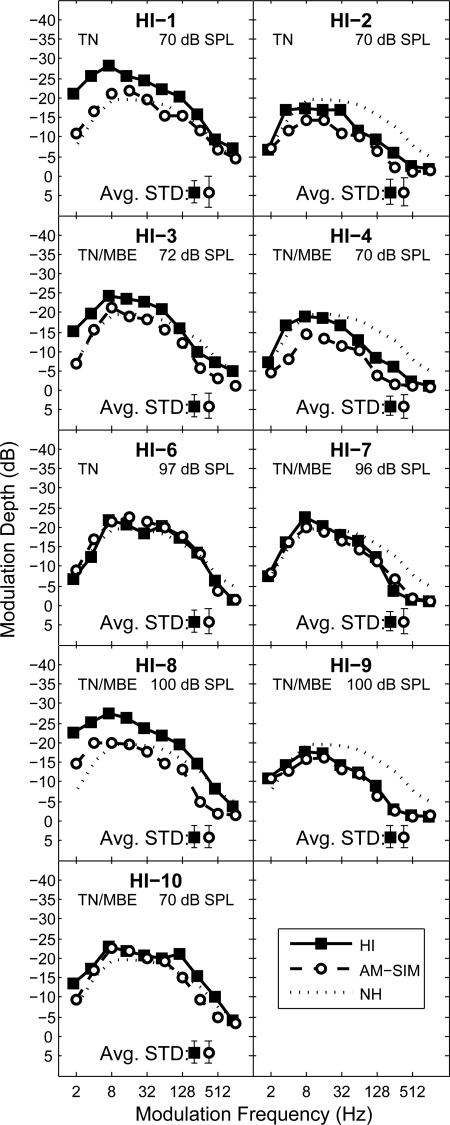

Figure 5.

Measured TMTFs as a function of modulation frequency. Each panel provides results for an individual HI listener (filled squares) and mean data for the corresponding AM-SIM group (unfilled circles). Also plotted in each panel is the average NH TMTF copied from Fig. 4 (dotted line). The hearing-loss-simulation method (TN or TN∕MBE) and the TMTF stimulus level (in dB SPL) employed for each HI listener are provided within each of the nine panels. Average STD across modulation frequency is shown for the HI listeners and average STD across modulation frequency and listener is shown for the AM-SIM groups.

The task for each trial was to select the interval containing the modulated noise burst. Modulation depth in dB [i.e., 20 log(Am)] was adjusted using a one-up, two-down rule to estimate the value that yielded 70.7% correct (Levitt, 1971). The initial step size was 4 dB for the first two reversals and was reduced to 2 dB for an additional six reversals. The threshold was calculated as the mean modulation depth at the final six reversals. Four repetitions were conducted at each modulation frequency. Each repetition consisted of one run at each of the 10 modulation frequencies presented in random order. For each listener, thresholds were averaged across the four measurements obtained at each modulation frequency.

RESULTS

Absolute thresholds and simulation thresholds

The measured HI-listener and simulated-loss thresholds are shown in Fig. 3. The HI-listener data points are the average of two measurements, while the AM-SIM group points are the average of six measurements (two measurements for each of the three listeners within a group). In addition to these two sets of data points, each panel also shows the average thresholds for each AM group without simulated loss. As with the simulated-loss data points, these data points are the average of six measurements (two per listener).

In general, the simulated-loss listeners show elevated thresholds that are within 5 dB (and, in the majority of cases, within 2 dB) of the desired, HI-listener thresholds. The one exception to this behavior involves the thresholds for HI-10 at 4 kHz. In this case the AM-SIM group has thresholds that are approximately 10–12 dB higher than those of the HI listener. This discrepancy resulted from the steep increase (over 80 dB) in hearing threshold between 4 and 8 kHz. The energy of the TN in the frequency region around 8 kHz led to downward masking at 4 kHz.

TMTF results

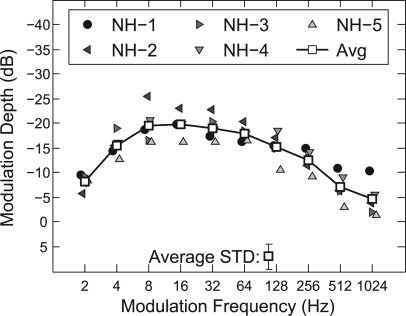

Figure 4 shows the measured TMTFs for each of the five NH listeners who were tested without simulated loss and their average results at each modulation frequency. The mean standard deviation (STD) across modulation frequencies and listeners, also shown on the plot, was 2.6 dB. Lower levels of modulation depth indicate better performance in the SAM detection task. These results show that modulation detection is best for modulation frequencies in the range 8 to 64 Hz and decreases for frequencies both above (at a rate of roughly 3 dB∕oct) and below (at a rate of roughly 6 dB∕octave) this range. The shape of the TMTF curve for the NH group is similar to that reported by Viemeister (1979) for NH listeners using gated 500-ms stimuli (see Fig. 5 from that paper). The low-frequency roll-off in performance observed here is characteristic of the use of gated shorter-duration signals and does not occur for continuous noise carriers or longer-duration periods of modulation (see Viemeister, 1979; Sheft and Yost, 1990). The maximal sensitivity in our NH group (−19 dB averaged across the 8–64 Hz range of modulation frequencies) was roughly 2 dB worse than that of Viemeister (1979) for a similar stimulus configuration, and the rate of decline in performance for modulation rates in the range 64 to 1024 Hz was similar (roughly 3–4 dB∕oct) for the two sets of data.

Figure 4.

Measured TMTFs as a function of modulation frequency for a subset of five NH listeners without simulated hearing loss. The solid line and open-squares indicate the average TMTF of these listeners. Average STD across modulation frequency and listener is also shown.

Figure 5 shows the measured TMTFs for the nine HI listeners and their corresponding AM-SIM groups. The average TMTF of the NH group from Fig. 4 is also shown as a dotted line in each of these plots. The mean STD across modulation frequencies and listeners within each group is also shown on the plots. These STDs, which ranged from 2.7 to 4.1 dB, were similar across HI listeners and between HI-listeners and their corresponding AM-SIM groups. For each of the nine HI listeners, a separate two-way ANOVA was conducted on the TMTF threshold measurements of the HI listener, the AM-SIM listeners corresponding to that listener, and the NH listeners. The ANOVAs tested for significance at the 0.01 level for the two main factors of modulation frequency and listener group (HI, AM-SIM, and NH), as well as for their interaction.

As expected, the effect of modulation frequency was highly significant for each of the nine analyses (F values ranged from 60.94 to 157.52, df (9,230), p < 0.01). The shape of the TMTF for the HI listeners generally followed that of the NH listeners. Differences in the shape of the TMTFs among the HI, AM-SIM, and NH listeners, however, are reflected in the significance of the interaction between the two main factors, and are discussed along with the group effect for each HI listener below.

For HI-6, no group effect was present [F(2, 230) = 2.45, p = 0.08] indicating statistical equivalence of the performance of HI-6, the AM-SIM group, and the NH group. A significant effect of group was observed in the remaining eight listeners [in all cases, F(2, 230) > 20.89, p < 0.01] and was further assessed using a post hoc Scheffe test of significance at the 0.05 level. For the comparisons between the mean for NH listeners and the individual HI listeners, performance was significantly better than NH for HI-1, HI-3, HI-8, and HI-10, and significantly worse for HI-2, HI-4, and HI-9. For the comparison of the HI listeners versus their AM-SIM groups, performance was significantly better for six of the nine HI listeners: HI-1, HI-2, HI-3, HI-4, HI-8, and HI-10, and equivalent for the remaining three HI listeners: HI-6, HI-7, and HI-9. For the first six listeners, the mean RMS difference between the HI and AM-SIM TMTFs was 4.9 dB, and for the remaining three listeners, the RMS difference was 1.7 dB.

A significant effect for the interaction between modulation frequency and group was observed for listeners HI-2 through HI-10 [with F(18, 230) > 2.26, p < 0.01], but not for HI-1 [F(18, 230) = 1.40, p = 0.13)]. The significant interaction implies a difference in the shapes of the TMTFs across the three groups. For the most part, these differences in the shape of the TMTFs arise from differences in performance at the higher modulation rates, as seen both in the modulation frequency at which performance begins to decline as well as in the rate of decline.

Another option for analyzing the TMTF data is to fit the TMTFs with a lowpass filter function (see Bacon and Gleitman, 1992):

| (5) |

where y(fm) is the fitted function (dB), fm is the modulation frequency (Hz), and (k,γ) are the parameters that describe the lowpass filter function. The parameter k represents overall performance and the value γ is analogous to a lowpass cut-off frequency. A lowpass filter fit to a specific, measured TMTF(fm) is generated by determining values of k and γ that minimize the squared error between TMTF(fm) and y(fm). The optimal-fit (k,γ) parameters may then be transformed into an informationally equivalent pair of parameters that describe the lowpass filter: the filter dc value and the filter time constant τ:

| (6) |

| (7) |

where fc = lowpass cutoff frequency= 0.414 γ.

The dc value of the filter is the value of the TMTF extrapolated to a modulation frequency of 0 Hz. The time constant τ describes the modulation frequency above which the sensitivity begins to decrease (i.e., the −3 dB frequency of the lowpass filter).

Table TABLE II. lists the dc and τ values for filters fitted to the TMTFs of the 9 individual HI listeners and the corresponding average AM-SIM groups for modulation frequencies ranging from 8 to 1024 Hz. TMTF data for fm = 2 and 4 Hz were disregarded to prevent the low-frequency TMTF roll-off from influencing the filter fit. The final rows of Table TABLE II. show mean and STDs of the dc and τ values over all HI listeners and over all AM-SIM listeners. For reference, parameters that fit the average NH data over the same frequency range are dc = −20.3 dB and τ = 2.2 ms.

Table 2.

Parameters describing the lowpass-filter fit to TMTF data for modulation frequencies from 8–1024 Hz.

| dc (dB) | τ (ms) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Filter parameter | HI | AM-SIM | HI | AM-SIM |

| LISTENER | ||||

| HI-1 | −27.7 | −21.1 | 4.5 | 2.7 |

| HI-2 | −17.1 | −12.9 | 2.8 | 1.9 |

| HI-3 | −25.1 | −20.1 | 4.8 | 4.8 |

| HI-4 | −18.7 | −12.6 | 3.9 | 2.0 |

| HI-6 | −22.5 | −23.9 | 3.4 | 4.6 |

| HI-7 | −22.9 | −19.7 | 7.1 | 4.1 |

| HI-8 | −28.2 | −20.4 | 6.0 | 4.7 |

| HI-9 | −17.2 | −15.4 | 3.6 | 2.8 |

| HI-10 | −23.3 | −23.2 | 2.5 | 4.6 |

| Mean | −22.5 | −18.8 | 4.3 | 3.6 |

| STD | 4.2 | 4.2 | 1.5 | 1.2 |

Averaged across listeners, the dc values were −22.5 dB for the HI listeners and −18.8 dB for the AM-SIM groups and the τ values were 4.3 and 3.6 ms, respectively. The effectiveness of the two types of simulations in reproducing the TMTF results of the HI listeners was examined by averaging dc and τ values for the three TN simulations (HI-1, HI-2, and HI-6) and for the six TN∕MBE simulations (the remaining listeners). For the TN simulations, the mean dc values were −22.4 dB for HI and −19.3 dB for AM-SIM and the mean τ values were 3.6 and 3.1 ms, respectively. For the TN∕MBE simulations, the mean dc values were −22.6 dB for HI and −18.6 dB for AM-SIM and the mean τ values were 4.6 and 3.8 ms, respectively. For both types of simulations, the dc sensitivity of the HI listeners was greater (by 3–4 dB) than for the AM-SIM groups and the τ values were larger (indicating lower cutoff frequencies).

The fits shown in Table TABLE II. were also considered across all HI listeners by calculating the Pearson correlation coefficients between the HI and average AM-SIM for the filter-fit parameter values. These calculations revealed that, although on average the HI listeners exhibited dc values that were 3.7 dB more sensitive than those of the AM-SIM listeners, the dc values of the HI and AM-SIM listeners were significantly correlated (ρ = 0.74, p = 0.023). The τ values of the HI listeners were somewhat higher than those of the AM-SIM listeners (averaging 4.3 ms versus 3.6 ms) and indicative of lower values of the cutoff frequency of the lowpass filter. No correlation was found between the τ values of the HI and AM-SIM listeners (ρ = 0.3, p = 0.43).

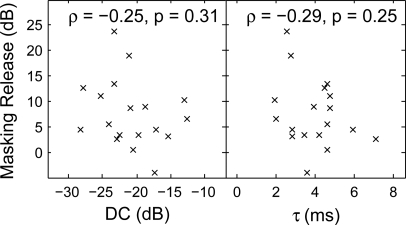

Relation between TMTF and masking release

The relationship between performance on the TMTF task and speech-reception thresholds in noise was examined using speech-intelligibility data from Desloge et al. (2010) on the same set of HI and AM-SIM listeners. Individual dc or τ values were compared with the S∕N required for 50%-correct reception of HINT sentences (Nilsson et al., 1994) in 10-Hz interrupted noise and with the magnitude of release from masking (defined as the difference between S∕N in continuous and interrupted noise) in a condition employing speech in 80-dB noise under NAL-RP amplification (Dillon, 2001, pp. 239–242). Masking release is plotted as a function of dc and τ values for individual HI listeners and for mean AM-SIM results in Fig. 6. Neither of these correlations was found to be significant (dc values: ρ = −0.25, p = 0.31; τ values: ρ = −0.29, p = 0.25). A similar lack of correlation was observed between S∕N in interrupted noise and either of the TMTF parameters (dc values: ρ = 0.23, p = 0.35; τ values: ρ = 0.32, p = 0.20).

Figure 6.

Masking release (MR; defined as the difference in speech thresholds for continuous and temporally fluctuating noise) plotted as a function of dc sensitivity in dB (left panel) and τ in ms (right panel). The ρ and p values of a cross-correlation analysis of MR to both dc and τ are also indicated.

DISCUSSION

The hearing-loss simulations were capable of reproducing the threshold elevations associated with the hearing losses of the individual HI listeners. In nearly all cases, the simulated hearing losses were within 5 dB of the target loss, with the exception of the 4000 Hz threshold for HI-10 in which the simulation resulted in a 10-dB greater loss than the target.

Despite this agreement with threshold elevation, the simulation was only partially successful in reproducing the TMTFs of the HI listeners. On average, the TMTFs of the HI listeners showed higher sensitivity than those of the NH listeners (without hearing-loss simulation) in terms of fitted dc values (−22.5 dB for HI versus −20.3 dB for NH) but exhibited substantially larger-than-normal values of τ (4.3 ms versus 2.1 ms). Thus, the cutoff frequency of the lowpass filter fit to the TMTFs was nearly an octave lower for the HI than the NH listeners (37.0 Hz versus 72.3 Hz). A comparison of the HI listeners to the AM-SIM groups also showed higher sensitivity in terms of fitted dc values (−22.5 dB for HI versus −18.8 dB for AM-SIM) and larger τ values (4.3 ms versus 3.6 ms corresponding to cutoff frequencies of 37.0 Hz versus 44.2 Hz). The dc values were well correlated between the hearing-impaired listeners and their simulated-loss counterparts, although τ values were not. Both methods of hearing loss simulation (TN and TN∕MBE) led to similar patterns in predicting the performance of the HI listeners: a lower overall sensitivity but a higher cutoff frequency.

To identify possible reasons why the individual HI listeners might outperform the corresponding AM-SIM group in the TMTF task, it is useful to consider why HI listeners might outperform NH listeners without simulated hearing loss on the same task. Generally, previous studies of TMTFs in HI listeners have indicated that HI performance is either similar to or slightly inferior to that of NH listeners when comparisons are made at equivalent SLs or SPLs (e.g., Bacon and Viemeister, 1985; Formby, 1987). Some studies, however, have reported cases of superior performance for HI than for NH listeners (Bacon and Gleitman, 1992; Moore et al., 1992). Bacon and Gleitman (1992) measured TMTFs as a function of level for NH listeners and for listeners with relatively flat mild-to-moderate hearing loss over a 30- to 40-dB range of broadband noise levels. For comparisons of NH and HI listeners for signals presented at equal SPL, there was substantial overlap in the performance of the two groups. For comparisons made at equal SL, however, the HI listeners tended to be more sensitive than the NH listeners for stimuli presented at 20 dB SL, although the two groups were similar at 30 dB SL. Moore et al. (1992) also found slightly better modulation detection for HI than for NH listeners using a narrowband noise carrier, when tested at equal SLs that ranged from 8 to 25 dB. Moore et al. (1996) performed a modulation-matching task between the normal and impaired ears of three listeners with unilateral hearing loss. The reference stimuli were 1000-Hz tones that were modulated at rates in the range 4–32 Hz at three modulation depths ranging from 6 to 18 dB in peak-to-valley ratio. The stimuli were presented at equal-loudness levels in the two ears, as derived from a loudness-matching experiment using unmodulated 1000-Hz tones. The results of the modulation-matching task indicated that, for a given modulation depth in dB in the impaired ear, the mean matching modulation depth in the normal ear was 2.4–2.5 times as large (averaged over modulation rates and listeners) and was roughly equivalent to the slopes of the recruitment functions. Moore et al. thus concluded that loudness recruitment played a strong role in the higher sensitivity to modulation observed for the impaired ear of listeners with unilateral loss.

If loudness recruitment does play a strong role in superior HI-listener performance on the TMTF task relative to NH listeners, then one explanation of the inferior AM-SIM performance in the current study is that the hearing-loss simulations failed to reproduce adequately the loudness recruitment of the corresponding HI listener. Recall that the current study simulated hearing loss using either TN or TN∕MBE depending upon the severity of the hearing loss. Although both TN and MBE simulations of hearing loss have been shown to reproduce some of the effects of loudness recruitment (Villchur, 1974), the two techniques do so in different ways.

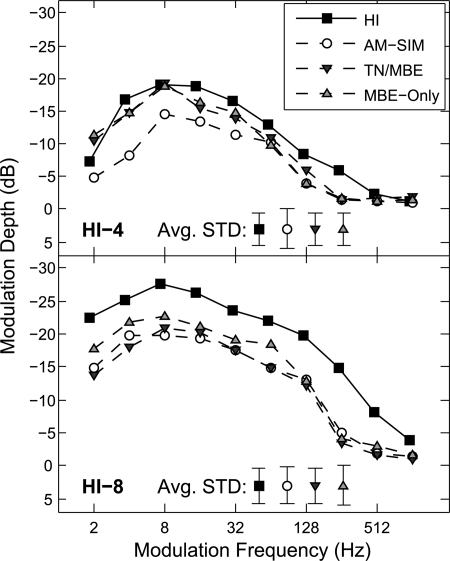

To determine whether the method of simulation may have played a role in the results obtained with the AM-SIM groups in the current study, we conducted further tests simulating the loss of two HI listeners whose modulation sensitivity exceeded that of their AM-SIM groups (HI-4 with a high-frequency loss and HI-8 with a flat loss). The losses of both these listeners were originally simulated using a combination of TN∕MBE. In the follow-up testing, we examined TMTF performance using both the original simulation and a simulation employing only MBE. For each of three highly experienced NH listeners (ranging in age from 39 to 61 years with a mean age of 52.3 years), two modulation-detection threshold measurements were obtained at each modulation frequency under each mode of simulation for each of the two HI listeners.

The mean results are shown in Fig. 7, which repeats the HI and AM-SIM data from Fig. 5 together with the additional TN∕MBE and MBE-only data from the additional NH listeners. For HI-4 (top panel), the lowpass filter fits to the new data yielded dc values of −16.2 and −16.6 dB and τ values of 3.3 and 4.0 ms for the TN∕MBE and MBE-only simulations, respectively. These simulations produced TMTFs that were similar to each other and to that of HI-4, which indicates that individual differences among listeners in the AM-SIM groups may have been responsible for the poor AM-SIM match seen originally. For HI-8 (bottom panel), the lowpass filter fits for the new data yielded dc values of −21.4 and −23.4 dB and τ values of 6.0 and 6.8 ms for the TN∕MBE and MBE-only simulations. These simulations produced TMTFs that were similar to each other and showed similar τ to that of HI-8 (6.0 ms). The dc values, however, showed lower sensitivity than that of HI-8 (−28.2 dB versus −21.4 and −23.4 dB for TN∕MBE and MBE-only, respectively); thus, the new simulation based on multiband expansion alone was still not capable of reproducing the sensitivity of HI-8 on the TMTF task.

Figure 7.

Measured TMTFs as a function of modulation frequency for HI-4 (top panel) and HI-8 (bottom panel) and for their corresponding AM-SIM groups. Two other sets of simulated-loss data are provided on a different set of NH listeners: TN∕MBE and MBE-only.

Another possibility for the decreased sensitivity of the AM-SIM groups lies in the use of masking noise for the hearing loss simulations. The random amplitude fluctuations of additive masking noise are known to affect modulation detection (Dau et al., 1997a,b). This issue can be addressed by examining the results associated with HI-4 in Fig. 7 for the additional listeners using TN∕MBE and MBE-only simulations. Specifically, the TN∕MBE simulation for this listener was achieved primarily using TN. The MBE α factor for this loss was only 7 dB, which meant that the MBE component of the TN∕MBE simulation accounted for a maximum of 7 dB of the threshold shifts. Thus, comparing TN∕MBE and MBE-only performance is roughly equivalent to comparing the TN (with 80-dB-SPL additive masking noise) and MBE-only (with no masking noise) simulations. In this case, the performance was indistinguishable for these two very different simulations, which suggests that fluctuations in the additive masking noise had only a minimal impact on the TMTF. A similar pattern was observed in the TN∕MBE and MBE- only data for HI-8 shown in Fig. 7, although the HI-8 α factor was somewhat higher at 10 dB.

Another concern regarding recruitment of the MBE used in the original TN∕MBE AM-SIM simulations and the additional MBE-only simulations described above is that the MBE processing uses smoothed signal envelopes when determining the level-dependent gain that is applied to the processed signal. Specifically, the envelopes are filtered by a 100-Hz lowpass filter, which smoothes the MBE-simulation gains over time to prevent “choppiness” in the processed signal. For SAM stimuli such as those used in this TMTF study, the main effect of this smoothing is that, for the higher modulation frequencies, the MBE simulation output exhibits a lower modulation expansion characteristic than expected based on the MBE input-to-output level mapping curve. A similar effect was shown for a real-time MBE system by Lum and Braida (1997). This reduction in SAM expansion for the higher modulation frequencies may explain the behavior evident in Fig. 7 for the additional NH listeners under a simulation of HI-8. As described above, the MBE simulation yielded TMTF performance that was 1–4 dB more sensitive than that with the TN∕MBE simulation for the lower modulation frequencies. For the higher modulation frequencies, however, the MBE simulation provided no TMTF performance benefit. This may also explain the original data for HI-10, where the AM-SIM performance was similar to that of the HI listener for modulation frequencies below 64 Hz but worse for modulation frequencies above 128 Hz.

Finally, the hearing-loss simulations used in the current study did not attempt to match the individual loudness-recruitment patterns of the HI listeners. Instead, a “standard” recruitment range spanning from each HI listener’s threshold-of-hearing to 100 dB HL was used. Had loudness recruitment been more precisely matched, it is possible that the TMTFs of the AM-SIM listeners would have more closely mimicked the TMTFs of the HI listeners. The effect of the recruitment function can be addressed in future work by adjusting the level of full recruitment (the REC point in Fig. 2) in TN∕MBE simulations of a given hearing loss. Lowering the REC points below the level used in the current simulations (100 dB HL within each band) will result in a higher expansion ratio than that used here. Such an adjustment may lead to lower TMTF thresholds and a better match of the simulation to the HI data.

Although the ability to follow amplitude modulation has been hypothesized to be a potential factor in the ability to take advantage of momentary increases in S∕N in temporally fluctuating noise (Takahashi and Bacon, 1992), no significant correlations were observed between the TMTFs and release from masking (see Fig. 7). This result corroborates that reported previously by Takahashi and Bacon (1992) who also found no correlation between modulation-detection ability and release from masking in elderly listeners. Other types of measurements of temporal-processing ability, however, have been shown to be correlated to masking release in HI listeners. George et al. (2006), for example, showed that the magnitude of masking release for speech reception in HI listeners was significantly correlated with a measurement of the width of a temporal gap necessary for detecting a frequency-swept signal in an interrupted noise with a 50% duty cycle. It may be that the measurements of George et al. are related to different auditory abilities in the temporal domain than those required for modulation detection.

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

The current study examined the use of simulation techniques based on the use of additive noise and multiband expansion to reproduce the TMTFs of HI listeners. Despite the accuracy of the simulations for reproducing the threshold elevations associated with cochlear hearing loss, the simulations were not capable of reproducing the TMTFs of individual HI listeners. On average, compared to NH listeners without simulated loss, the HI-listener TMTFs were characterized by 2.5 dB higher modulation-depth sensitivity and modulation cutoff frequencies that were half as large (72.3 Hz for NH versus 37.0 Hz for HI). Compared to AM-SIM listeners, the HI-listener TMTFs were characterized by 3.7 dB higher sensitivity and modulation cutoff frequencies that were roughly 20% lower (44.2 Hz for AM-SIM versus 37.0 Hz for HI). These results indicate that the hearing-loss simulations were able to reproduce some of the lowered modulation cutoff frequency evident in the HI listeners compared to NH listeners but failed to reproduce their increased modulation-depth sensitivity. Estimates of sensitivity were well correlated between the hearing-impaired listeners and their simulated-loss counterparts, although estimates of cutoff frequency were not.

The greater sensitivity of the HI listeners may be related to a more rapid loudness growth than what was achieved by the simulations. One approach to improving the simulations may be through more faithful reproduction of loudness growth. The MBE simulation of recruitment might be improved through the use of more accurate input-to-output mapping functions as well as less temporal envelope smoothing. It should be noted that increased use of MBE hearing-loss simulations would increase the difference between absolute stimulus levels presented to the HI and simulated-loss listeners. Further, results from the current study suggest that the use of MBE-only simulations as opposed to a primarily TN simulation would yield little difference in TMTF performance.

These simulation techniques have been previously shown to be generally effective for reproducing the speech-reception performance of HI listeners in terms of S∕N required for 50%-correct intelligibility of sentences in backgrounds of continuous and temporally modulated noise and in terms of release from masking (Desloge et al., 2010). Even though one might assume that the ability to detect amplitude modulation (as measured by the TMTF) would relate to speech reception ability in a temporally fluctuating noise background, no significant correlations were found between TMTF performance (either in terms of overall sensitivity or cutoff frequency) and release from masking. Perhaps the accurate simulation of threshold elevation was more important than details of the simulation of TMTFs for speech reception in noise.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by Grant No. R01 DC00117 from the National Institutes of Health, NIDCD. The authors wish to thank Stephan Ewert for the AFC Software Package developed at the University of Oldenburg, Germany and Patrick M. Zurek for his helpful comments on previous versions of this manuscript. We also wish to thank Michael Akeroyd, Brian Moore, and an anonymous reviewer for their help in revising the manuscript.

Footnotes

In addition to broadband-noise carriers, TMTFs have also been obtained using sinusoidal carriers (Moore and Glasberg, 2001) and narrowband-noise carriers (Moore et al., 1992; Dau et al., 1997a,b).

Only sounds up to 100 dB SPL were presented in the current study.

Twenty-six of the twenty-seven listeners in the AM-SIM groups were the same as those who participated in the study of Desloge et al. (2010). The exception is the replacement of one listener in the AM-SIM group for HI-10.

References

- Bacon, S. P., and Gleitman, R. M. (1992). “Modulation detection in subjects with relatively flat hearing loss,” J. Speech Hear. Res. 35, 642–653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bacon, S. P., and Viemeister, N. F. (1985). “Temporal modulation transfer functions in normal and hearing-impaired listeners,” Audiology 24, 117–134. 10.3109/00206098509081545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bacon, S. P., Opie, J. M., and Montoya, D. Y. (1998). “The effects of hearing loss and noise masking on the masking release in temporally complex backgrounds,” J. Speech Hear. Res. 41, 549–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer, T., and Moore, B. C. J. (1993). “Effects of spectral smearing on the intelligibility of sentences in noise,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 94, 1229–1241. 10.1121/1.408176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein, J. G. W., and Grant, K. W. (2009). “Auditory and auditory-visual intelligibility of speech in fluctuating maskers for normal-hearing and hearing-impaired listeners,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 125, 3358–3372. 10.1121/1.3110132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buss, E., Hall, J. W., Grose, J. H., and Hatch, D. R. (1998). “Perceptual consequences of peripheral hearing loss: Do edge effects exist for abrupt cochlear lesions?,” Hear. Res. 125, 98–108. 10.1016/S0378-5955(98)00131-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dau, T., Kollmeier, B., and Kohlraush, A. (1997a). “Modeling auditory processing of amplitude modulation. I. Detection and masking with narrow- band carriers,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 102, 2892–2905. 10.1121/1.420344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dau, T., Kollmeier, B., and Kohlraush, A. (1997b). “Modeling auditory processing of amplitude modulation. II. Spectral and temporal integration,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 102, 2906–2919. 10.1121/1.420345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desloge, J. G., Reed, C. M., Braida, L. D., Perez, Z. D., and Delhorne, L. A. (2010). “Speech reception by listeners with real and simulated hearing impairment: Effects of continuous and interrupted noise,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 128, 342–359. 10.1121/1.3436522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillon, H. (2001). Hearing Aids (Thieme, New York: ), pp. 239–242. [Google Scholar]

- Dubno, J. R., and Schaefer, A. B. (1992). “Comparison of frequency selectivity and consonant recognition among hearing-impaired and masked normal-hearing listeners,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 91, 2110–2121. 10.1121/1.403697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duchnowski, P. (1989). “Simulation of sensorineural hearing impairment,” M.S.E.E. thesis, Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, MIT, Cambridge. [Google Scholar]

- Duchnowski, P., and Zurek, P. M. (1995). “Villchur revisited: Another look at AGC simulation of recruiting hearing loss,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 98, 3170–3181. 10.1121/1.413806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg, L. S., Dirks, D. D., and Bell, T. S. (1995). “Speech recognition in amplitude-modulated noise of listeners with normal and listeners with impaired hearing,” J. Speech Hear. Res. 38, 222–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Festen, J. M., and Plomp, R. (1990). “Effects of fluctuating noise and interfering speech on the speech-reception threshold for impaired and normal hearing,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 88, 1725–1736. 10.1121/1.400247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Florentine, M., and Buus, S. (1984). “Temporal gap detection in sensorineural and simulated hearing impairments,” J. Speech Hearing Res. 27, 449–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Florentine, M., Fastl, H., and Buus, S. (1988). “Temporal integration in normal hearing, cochlear impairment, and impairment simulated by masking,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 84, 195–203. 10.1121/1.396964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Florentine, M., Reed, C. M., Rabinowitz, W. M., Braida, L. D., and Durlach, N. I. (1993). “Intensity perception. XIV. Intensity discrimination in listeners with sensorineural hearing loss,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 94, 2575–2586. 10.1121/1.407369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Formby, C. (1987). “Modulation threshold functions for chronically impaired Meniere patients,” Audiology 26, 89–102. 10.3109/00206098709078410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George, E. J., Festen, J. M., and Houtgast, T. (2006). “Factors affecting masking release for speech in modulated noise for normal-hearing and hearing-impaired listeners,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 120, 2295–2311. 10.1121/1.2266530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasberg, B. R., and Moore, B. C. J. (1992). “Effects of envelope fluctuations on gap detection,” Hear. Res. 64, 81–92. 10.1016/0378-5955(92)90170-R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graf, I. J. (1997). “Simulation of the effects of sensorineural hearing loss,” M.S.E.E. thesis, Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, MIT, Cambridge. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, K. W., Summers, V., and Leek, M. R. (1998). “Modulation rate detection and discrimination by normal-hearing and hearing-impaired listeners,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 104, 1051–1060. 10.1121/1.423323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins, J. E., and Stevens, S. S. (1950). “The masking of pure tones and of speech by white noise,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 22, 6–13. 10.1121/1.1906581 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Humes, L. E. (1990). “Masking of tone bursts by modulated noise in normal, noise-masked normal, and hearing-impaired listeners,” J. Speech Hearing Res. 33, 3–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamore, P. J. J., Verweij, C., and Brocaar, M. P. (1984). “Reliability of auditory function tests in severely hearing-impaired and deaf subjects,” Audiology 23, 453–466. 10.3109/00206098409070085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitt, H. (1971). “Transformed up-down methods in psychoacoustics,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 49, 467–477. 10.1121/1.1912375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzi, C., Husson, M., Ardoint, M., and Debruille, X. (2006). “Speech masking release in listeners with flat hearing loss: Effects of masker fluctuation rate on identification scores and phonetic feature reception,” Int. J. Audiol. 45, 487–495. 10.1080/14992020600753213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lum, D. S., and Braida, L. D. (1997). “DSP implementation of a real-time hearing loss simulator based on dynamic expansion,” in Modelling Sensorineural Hearing Loss, edited by Jesteadt W. (Erlbaum L., Mahwah, NJ: ), pp. 113–130. [Google Scholar]

- Milner, P., Braida, L. D., Durlach, N. I., and Levitt, H. (1984). “Perception of filtered speech by hearing-impaired listeners,” in Speech Recognition by the Hearing Impaired, edited by Elkins E. (American Speech Language Hearing Association, Rockville, MD: ), pp. 30–41. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, B. C. J., and Glasberg, B. R. (1993). “Simulation of the effects of loudness recruitment and threshold elevation on the intelligibility of speech in quiet and in a background of speech,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 94, 2050–2062. 10.1121/1.407478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore, B. C. J., and Glasberg, B. R. (2001). “Temporal modulation transfer functions obtained using sinusoidal carriers with normally hearing and hearing-impaired listeners,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 110, 1067–1073. 10.1121/1.1385177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore, B. C. J., Glasberg, B. R., Alcántara, J. I., Launer, S., and Kuehnel, V. (2001). “Effects of slow- and fast-acting compression on the detection of gaps in narrow bands of noise,” Br. J. Audiol. 35, 365–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore, B. C. J., Glasberg, B. R., and Vickers, D. A. (1995). “Simulation of the effects of loudness recruitment on the intelligibility of speech in noise,” Brit. J. Audiol. 29, 131–143. 10.3109/03005369509086590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore, B. C. J., Shailer, M. J., and Schooneveldt, G. P. (1992). “Temporal modulation transfer functions for band-limited noise in subjects with cochlear hearing loss,” Brit. J. Audiol. 26, 229–237. 10.3109/03005369209076641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore, B. C. J., Vickers, D. A., Glasberg, B. R., and Baer, T. (1997). “Comparison of real and simulated hearing impairment in subjects with unilateral and bilateral cochlear hearing loss,” Brit. J. Audiol. 31, 227–245. 10.3109/03005369709076796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore, B. C. J., Wojtczak, M., and Vickers, D. A. (1996). “Effect of loudness recruitment on the perception of amplitude modulation,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 100, 481–489. 10.1121/1.415861 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nejime, Y., and Moore, B. C. J. (1997). “Simulation of the effect of threshold elevation and loudness recruitment combined with reduced frequency selectivity on the intelligibility of speech in noise,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 102, 603–615. 10.1121/1.419733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson, M., Soli, S. D., and Sullivan, J. A. (1994). “Development of the Hearing in Noise Test for the measurement of speech reception thresholds in quiet and in noise,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 95, 1085–1099. 10.1121/1.408469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oxenham, A. J., and Dau, T. (2004). “Masker phase effects in normal-hearing and hearing- impaired listeners: Evidence for peripheral compression at low signal frequencies,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 116, 2248–2257. 10.1121/1.1786852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters, R. W., Moore, B. C. J., and Baer, T. (1998). “Speech reception thresholds in noise with and without spectral and temporal dips for hearing-impaired and normally hearing people,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 103, 577–587. 10.1121/1.421128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed, C. M., Braida, L. D., and Zurek, P. M. (2009). “Review of the literature on temporal resolution in listeners with cochlear hearing impairment: A critical assessment of the role of suprathreshold deficits,” Trends Amplif. 13, 4–43. 10.1177/1084713808325412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon, R. V., Zeng, F.-G., Kamath, V., Wygonski, J., and Ekelid, M. (1995). “Speech recognition with primarily temporal cues,” Science 270, 303–304. 10.1126/science.270.5234.303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro, M. T., Melnick, W., and VerMeulen, V. (1972). “Effects of modulated noise on speech intelligibility of people with sensorineural hearing loss,” Ann. Otol. 81, 241–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheft, S., and Yost, W. A. (1990). “Temporal integration in amplitude modulation detection,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 88, 796–805. 10.1121/1.399729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg, J. C., and Gardner, M. B. (1937). “The dependence of hearing impairment on sound intensity,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 9, 11–23. 10.1121/1.1915905 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Summers, V., and Molis, M. R. (2004). “Speech recognition in fluctuating and continuous maskers: Effects of hearing loss and presentation level,” J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 47, 245–256. 10.1044/1092-4388(2004/020) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi, G. A., and Bacon, S. P. (1992). “Modulation detection, modulation masking, and speech understanding in noise in the elderly,” J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 35, 1410–1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner, C. W., Souza, P. E., and Forget, L. N. (1995). “Use of temporal envelope cues in speech recognition by normal and hearing-impaired listeners,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 97, 2568–2576. 10.1121/1.411911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Tasell, D. J., Soli, S. D., Kirby, V. M., and Widin, G. P. (1987). “Speech waveform envelope cues for consonant recognition,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 82, 1152–1161. 10.1121/1.395251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viemeister, N. F. (1979). “Temporal modulation transfer functions based upon modulation thresholds,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 66, 1364–1380. 10.1121/1.383531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villchur, E. (1973). “Signal processing to improve speech intelligibility in perceptive deafness,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 53, 1646–1657. 10.1121/1.1913514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villchur, E. (1974). “Simulation of the effect of recruitment on loudness relationships in speech,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 56, 1601–1611. 10.1121/1.1903484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zurek, P. M., and Delhorne, L. A. (1987). “Consonant reception in noise by listeners with mild and moderate sensorineural hearing impairment,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 82, 1548–1559. 10.1121/1.395145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]