Abstract

The ability to probe for catalytic activities of enzymes and to detect their abundance in complex biochemical contexts has traditionally relied on a combination of kinetic assays and techniques such as western blots that use expensive reagents such as antibodies. The ability to simultaneously detect activity and isolate a protein catalyst from a mixture is even more difficult and currently impossible in most cases. In this manuscript we describe a chemical approach that achieves this goal for a unique family of enzymes called sirtuins using novel chemical tools, enabling rapid detection of activity and isolation of these protein catalysts. Sirtuin deacetylases are implicated in the regulation of many physiological functions including energy metabolism, DNA-damage response, and cellular stress resistance. We synthesized an aminooxy-derivatized NAD+ and a pan-sirtuin inhibitor that reacts on sirtuin active sites to form a chemically stable complex that can subsequently be crosslinked to an aldehyde-substituted biotin. Subsequent retrieval of the biotinylated sirtuin complexes on streptavidin beads followed by gel electrophoresis enabled simultaneous detection of active sirtuins, isolation and molecular weight determination. We show that these tools are cross reactive against a variety of human sirtuin isoforms including SIRT1, SIRT2, SIRT3, SIRT5, SIRT6 and can react with microbial derived sirtuins as well. Finally, we demonstrate the ability to simultaneously detect multiple sirtuin isoforms in reaction mixtures with this methodology, establishing proof of concept tools for chemical studies of sirtuins in complex biological samples.

The sirtuin enzymes are NAD+ dependent protein deacetylases broadly distributed in biology and implicated in the regulation of diverse processes within cells.1 Mammalian sirtuins SIRT1-7 regulate apoptosis,2 proliferation,3 stress resistance,4,5 and metabolism.6,7 Sirtuin localization in cells is compartmentalized. For example SIRT1, SIRT6 and SIRT7 are thought to be nuclear,8 whereas SIRT3, SIRT4 and SIRT5 are mitochondrial9 and SIRT2 is predominantly cytosolic although it can be nuclear as well.10 Sirtuins are expressed at different levels in distinct tissues, and stresses such as calorie restriction or fasting can affect their abundance.11 Current methods to detect sirtuin biochemical activity in complex mixtures such as lysates are cumbersome, and detection and quantification of individual sirtuins in lysed cells requires western blots. Problematically, current biochemical assays do not distinguish between the activities of sirtuin isoforms. Moreover, to detect each individual sirtuin, a distinct and relatively expensive antibody is required. Importantly, the ability to detect activity and determine identities of sirtuins in cells and tissues in a manner that is straightforward, simultaneous and rapid could provide accelerated investigation into sirtuin functions in a variety of disease states and physiological conditions.

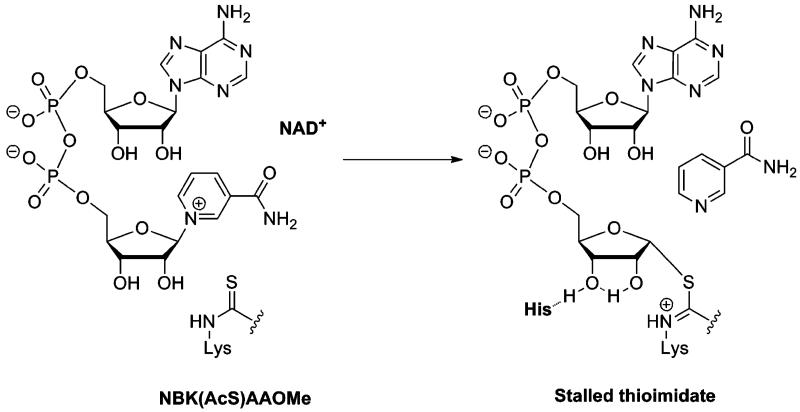

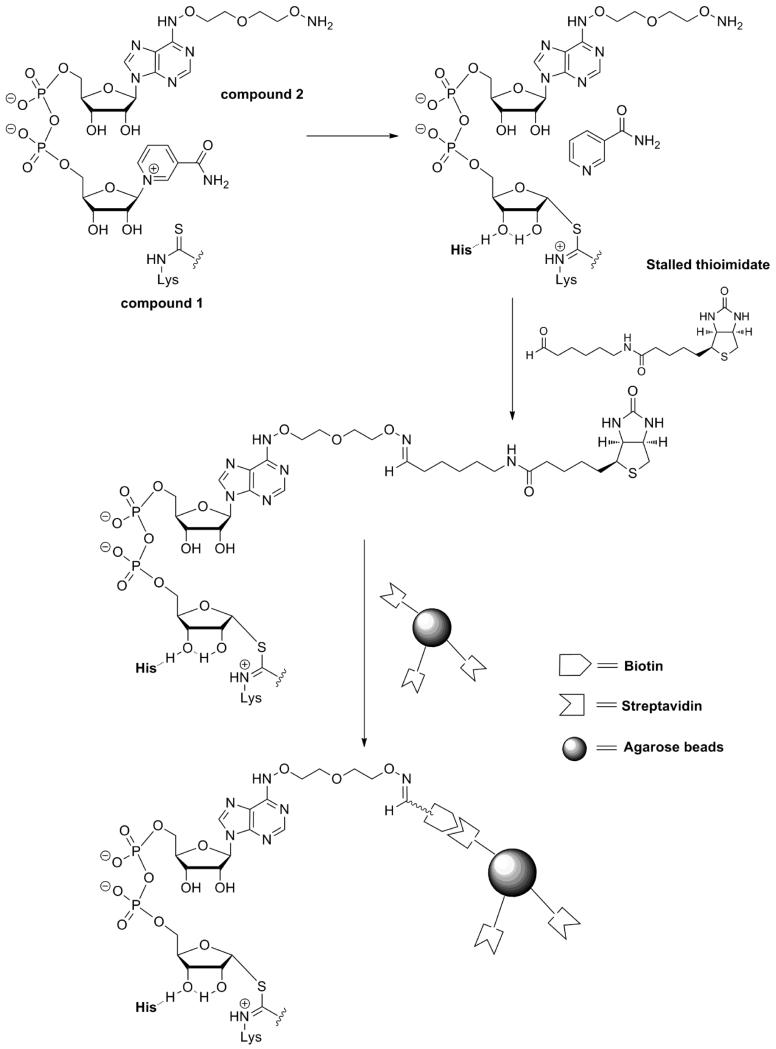

We sought to develop a technology that could simultaneously detect sirtuin activity in complex mixtures and to isolate the sirtuin thus detected. We required chemicals that could react at a sirtuin active site using the enzyme mechanism (detection of activity) to form a stable complex which could then be harvested (isolation of sirtuin). In principle, such a technology has the means to assess for isoform activity and could be used for quantitation and identification of the isolated sirtuins, by standard SDS-PAGE techniques. Interestingly, thioacetylated peptides react with NAD+ on sirtuin active sites to form kinetically stable thioimidate complexes,12 which have been characterized by X-ray crystallography13,14 (Scheme 1). The reaction that forms the thioimidate is analogous to the reactivity proposed for the reactions of NAD+ with acetylated substrates13,15 which react on sirtuin active sites to form reactive O-imidate complexes16,17 that are intermediates in deacetylation chemistry (Scheme 2).16 In considering desired properties of the thioacetyl-peptide, we realized that cross-reactivity against multiple sirtuin isoforms would be beneficial, so that one reagent could work for multiple sirtuins. The general reagent approach has been the basis of ‘activity-based profiling’ as pioneered by Cravatt and co-workers.18-20 Interestingly, N-thioacetyl-lysine peptide analogues of sirtuin substrates have already been reported to inhibit SIRT1, SIRT2 and SIRT3 catalyzed deacetylations with affinities in the nanomolar to low micromolar range.12,15,21 Thus, we were encouraged to identify a simple peptide sequence that could achieve broad cross-reactivity with human sirtuin isoforms.

Scheme 1.

Mechanism for sirtuin inhibition by thioacetylpeptides and 1.

Scheme 2.

Mechanism of sirtuin catalyzed deacetylation.

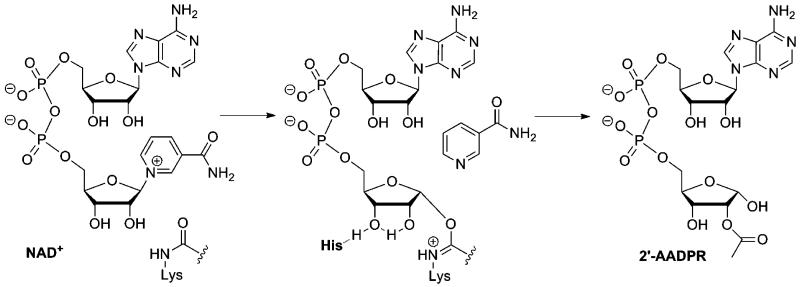

The simple benzoylated tripeptide: Nα-4-nitrobenzoyl-Nε-thioacetyl-lysinyl-alaninyl-alanine methyl ester, 1, (Fig. 1, See synthesis in Supplementary Information) was found to have suitable properties as a minimal structure that inhibits sirtuin enzymes. In Table 1, we report data that shows it inhibits SIRT1, SIRT2, SIRT3 with IC50 values in the low μM range although the IC50 for SIRT3 is above 100 μM. The compound also inhibits the Archaeoglobus fulgidus Af2Sir216 and Saccharomyces cerevisiae Sir2 with IC50 values in the same range, indicating we have identified a general sirtuin inhibitor (Table 1). These data provide evidence that this simple structure can act as a general reagent capable of reacting on sirtuin active sites, and inhibiting enzymatic activity presumably via thioimidate formation (Scheme 1). Consistent with this notion, inhibition by 1 was shown to be competitive with an acetylated peptide substrate on SIRT1 with Ki = 611 nM ± 248 nM (Fig. S2).

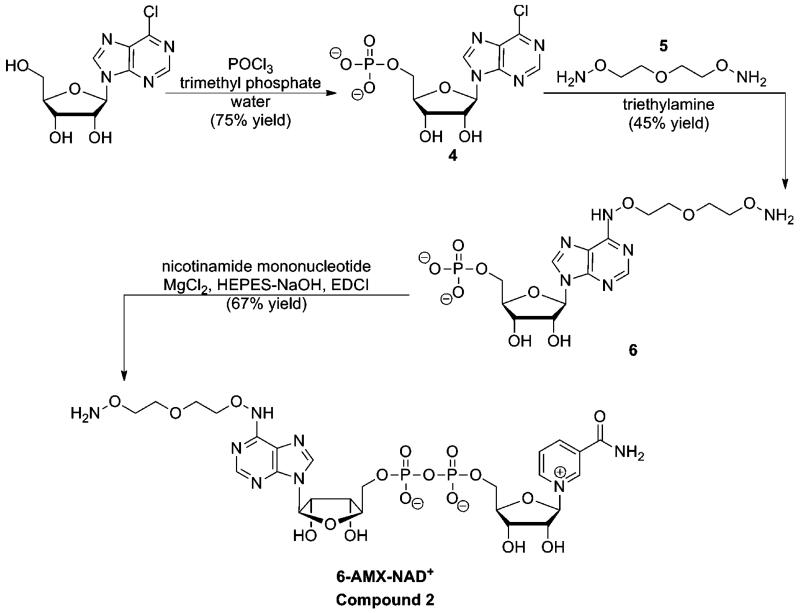

Fig. 1.

Structures of (1), 6-AMX-NAD+ (2)and N-biotinyl-6-aminohexanal (3).

Table 1.

Inhibition of sirtuin-catalyzed deacetylation by 1

| Sirtuin | Acetylated substrate | IC50 (μM) |

|---|---|---|

| Af2Sir2 | NBK(Ac)AAOMe | 131 ± 26.0 |

| Yeast Sir2 | H3mer | 19.5 ± 5.80 |

| SirT1 | p53mer | 6.5 ± 1.00 |

| SirT2 | p53mer | 13.1 ± 0.54 |

| SirT3 | H3mer | 272 ± 80.3 |

Assays were carried out at 37 °C for 30 to 60 min using purified sirtuin enzyme,NAD+, inhibitor, and substrates as specified in the Supplementary Information. Acetylated peptides are fully defined in the Supplementary Information and NBK(Ac)AAOMe is the acetylated peptide isostructural to 1. Data was plotted as percent enzyme activity remaining as a function of log[1] in nanomolar. Curve fits were generated using the following equation: v(%) = v(%)I − [v(%)I(10x)/(10x + IC50)]. v(%) represents percent enzyme activity remaining and v(%)I represents the initial enzyme activity of 100%. The variable x represents log[1] in nanomolar; where 10x is the concentration of 1 in nanomolar. IC50 values were calculated from this equation with relevant curves and data found in Fig. S1.

The ability of 1 to react at the active site to form a stable thioimidate complex on a variety of sirtuins accomplished a key criterion for our technology, with the next requirement that the thioimidate complexes could be cross-linked via peptide or by another feature of the thioimidate complex to a pulldown reagent, such as biotin which can be harvested by binding to avidin beads. To achieve crosslinkable thioimidate complexes, a chemically modified NAD+ was designed that could react to form the desired thioimidate, but could be chemically reacted to biotin after thioimidate formation. A modified NAD+ with a linker appended to the adenine ring at the 6 position was designed which is abbreviated 6-AMX-NAD+ (2, Fig. 1). Synthesis of this derivative is shown in Scheme 3. The presence of a terminal aminooxy functionality on the linker provides a reactive group that enables 6-AMX-NAD+ or thioimidate complexes derived from it to be crosslinked to a biotin modified with a reactive carbonyl. A condition for the linker is that it should not interfere with NAD+ function as a substrate, and inspection of several crystallographically determined sirtuins with NAD+22 or thioimidate bound13 convinced us that the 6-exocyclic-N position of the adenine ring of substrate is solvent accessible, and would readily accommodate the linker.

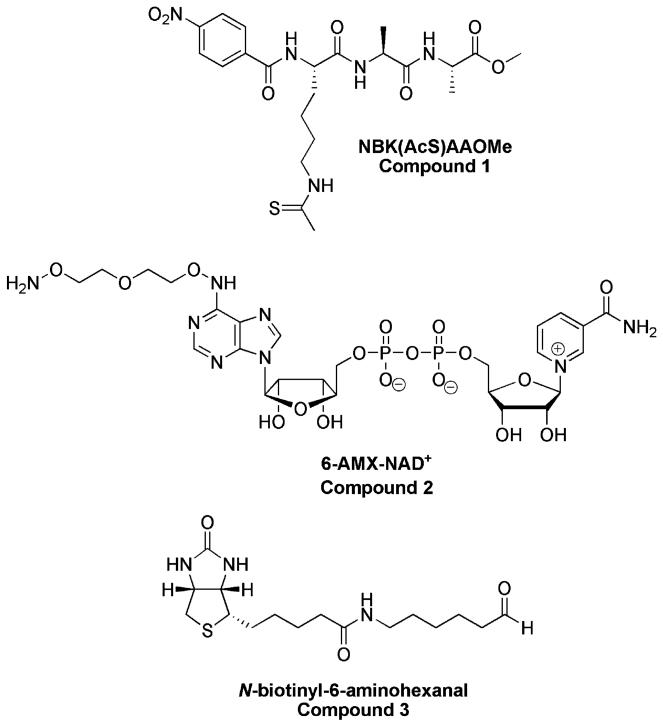

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of 6-AMX-NAD+.

In the imagined use of 6-AMX-NAD+, it would readily form the thioimidate 1 to form a kinetically stable complex (Scheme 4) that could be crosslinked to an aldehyde modified biotin (3, Fig. 1).23 Conjugate formation involving aminooxy or hydrazino groups24-26 has previously been used to interrogate functionalized sugars bearing reactive carbonyls.24-26 Based on precedent, in situ conjugate formation with an aminooxy group and an aldehyde was concluded to enable a proof of concept test of the technology. A specific advantage of aminooxy groups is their low predicted pKa, 6–7, allowing us to cross link NAD+ to biotin at neutral to slightly acidic pH, where chemistry on sirtuins occurs and where the thioimidate complexes are predicted to be stable. Subsequent capture of sirtuin-thioimidate-biotin conjugates could be obtained by avidin beads (Scheme 4). Subsequent analysis on gels provides molecular weights and abundance of captured sirtuins.

Scheme 4.

Model of avidin-biotin affinity capture of sirtuin enzymes using compounds 1–3.

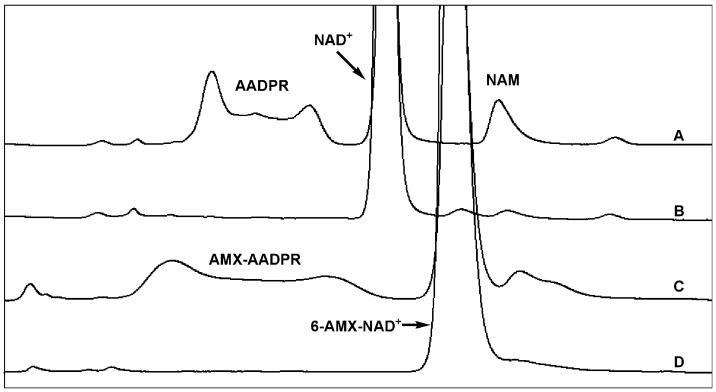

To validate our tools, several control experiments were performed to provide evidence that the constructs could function together. For example, evaluation of 6-AMX-NAD+ as a substrate proved its ability to support sirtuin catalysis. 6-AMX-NAD+ was able to support SIRT1 catalyzed deacetylation as evident from formation of 6-AMX-2′-and 3′-O-acetyl-ADPR (Fig. 2C), which was further verified by isolation and MALDI-MS (Fig. S3). Evaluation of steady state parameters for 6-AMX-NAD+ on SIRT1 provided a Km value of 231 μM (Fig. S4), which compares favorably with the Km value of NAD+, of 165 μM.27 Comparison of reaction under identical concentrations, substrates and conditions (Fig. 2A and 2C) established that 6-AMX-NAD+ reacts at a rate of 0.91 relative to the rate of NAD+ for SIRT1 catalysed deacetylation. Collectively, these data indicate that 6-AMX-NAD+ can act as a substrate in a manner that is highly similar to NAD+. In addition, to acting as a substrate, we demonstrate that 6-AMX-NAD+ supports full inhibition of SIRT1 by 1 (Fig. 2), consistent with the effective ability of 6-AMX-NAD+ to form a stabilized thioimidate complex. We further showed that 6-AMX-NAD+ and the thioacetyl-lysine inhibitor 1 form a thioimidate complex on SIRT1, as shown by detection of the thioimidate species by MALDI-TOF MS (Supplementary Information Fig. S6†).

Fig. 2.

HPLC chromatograms showing 6-AMX-NAD+, 2, is a substrate for SirT1: (A) reaction containing 500 μM NAD+, 500 μM of p53mer in 100 mM phosphate buffer pH 7.5 was initiated by addition of SirT1 to a final concentration of 10.7 μM. After incubation at 37 °C for 20 min, AADPR and NAM were formed; (B) reaction performed as in (A), with addition of 250 μM of 1; (C) reaction containing 500 μM 2, 500 μM of p53mer in 100 mM phosphate buffer pH 7.5 was initiated by addition of SirT1 to a final concentration of 10.7 μM. After incubation at 37 °C for 20 min, 6-AMX-AADPR and NAM were formed; (D) reaction performed as in (C), with addition of 250 μM of 1.

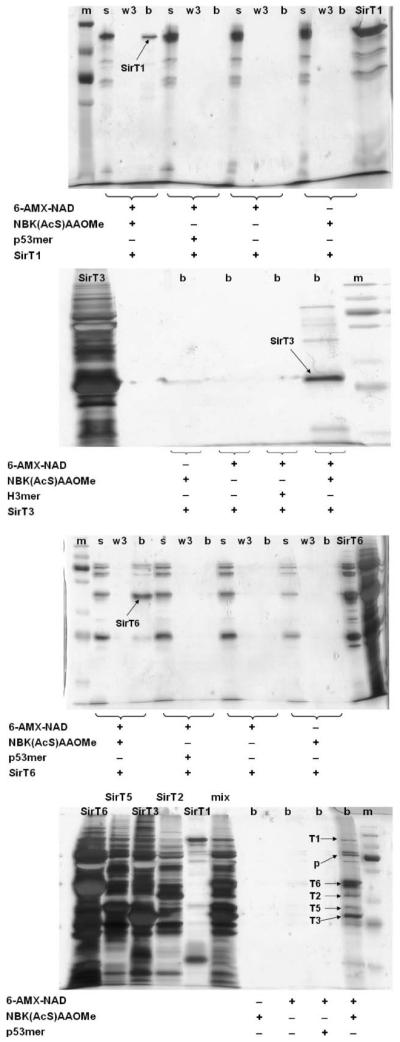

‘Sirtuin capture’ using the described chemical tools was demonstrated according to the sequence described in Scheme 4. 6-AMX-NAD+ was combined with 1 in a variety of reaction mixtures containing recombinantly expressed sirtuins SIRT1, SIRT3 and SIRT6 as shown in Fig. 3. Reaction conditions and procedures are provided in the legend. Recovered beads were loaded directly onto SDS-PAGE gels and proteins eluted from beads were visualized by silver staining. As evident from gel images, only reaction mixtures containing 1 and 6-AMX-NAD+ yielded beads containing bound sirtuins, likely because of the formation of stable thioimidates on the bound sirtuins. Acetylated peptide substrates could not function as effective reagents, presumably because O-imidate complexes are less kinetically stable (Fig. 3). Similar results were obtained with SIRT2 and SIRT5 (See Fig. S5). The same procedures were also able to capture recombinant S. cerevisiae Sir2, and the A. fulgidus sirtuin, Af2Sir2 (See Fig. S5). These data provide the first demonstration, to our knowledge, of general reagents that can be used to detect sirtuin biochemical reactivity and that can also capture the reactive sirtuins via a biotin conjugation strategy.

Fig. 3.

Representative SDS-PAGE results for sirtuin capture by 1 and 2. (A) SirT1; (B) SirT3; (C) SirT6; (D) mixed sirtuins. Reactions were typically performed in 300 mM phosphate buffer pH 7.5 in a total volume of 50 μL. A typical reaction contained 800 μM of 2 and 400 μM of 1, three control experiments were run at the same time: the first one contained 800 μM of 2 and 500 μM of an acetylated peptide substrate, p53mer for SirT1, H3mer for SirT3, p53mer for SirT6 and p53mer for sirtuin mixture (Sequences are found in Supplementary Information); the second control sample contained 800 μM of 2 only; and the third control had 400 μM of 1 only. Reactions were initiated by addition of enzyme, final concentrations 16.5 μM for SirT1, 11.5 μM for SirT3, 17.1 μM for SirT6. For the sirtuin mixture, final enzyme concentrations were 16.5 μM for SirT1, 12.5 μM for SirT2, 11.5 μM for SirT3, 13.6 μM for SirT5 and 17.1 μM for SirT6. Reactions were incubated at 37 °C for 30 min and then adjusted to pH 6 by addition of 25 μL of 300 mM phosphate buffer pH 4.25. Compound 3 was added to each sample to a final concentration of 1 mM, incubations were continued at room temperature for one hour. Then 50 μL of avidin agarose beads were added to each sample, and the reactions were allowed to incubate at room temperature for another hour. After removal of the supernatant, the beads were washed with 1 mM NAD+ in 300 mM phosphate buffer (3 × 100 μL), the washes were removed and saved for gel analysis. The beads were boiled in SDS-PAGE sample buffer for 10 min and subject to gel electrophoresis for analysis. s = supernatant; w3 = wash 3; b = beads; m = molecular weight marker, p = putative proteolyzed sirtuin fragments.

A further demonstration of the versatility of the sirtuin capture methodology is shown in the bottom gel of Fig. 3. In this instance, multiple partially purified recombinant sirtuins SIRT1, SIRT2, SIRT3, SIRT5 and SIRT6 were combined together and subjected as a mixture to the thioimidate sirtuin capture procedure. As can be seen, all relevant forms of sirtuins were recovered, including what appear to be proteolysis-cleaved forms of sirtuins.

This paper describes the first chemical method to isolate sirtuins intact from complex protein mixtures based on their reactivity to a common sirtuin inhibitor, wherein the mechanism of inhibition utilizes the catalytic mechanism to achieve stable complex formation. This methodology provides important proof of concept demonstration that it is possible to isolate multiple intact sirtuins from impure protein mixtures. In theory this methodology permits simultaneous assessment of reactivity, abundance, and determination of molecular weight of multiple sirtuin isoforms in a single assay. Conceivably the method could also be utilized to re-interogate isolated sirtuin biochemical properties since the sirtuin thioimidate complexes are thought to be only temporally stable, and are likely to release free enzyme after extended incubation in solution.15 As a demonstration of this possibility, the capture and subsequent rerelease of Af2Sir2 from beads was examined. Rereleased enzyme is active and recovery occurs in a time-dependent manner (Supplementary Information, Fig. S7†) consistent with slow reaction of the thioimidate to release enzyme.

Some improvements are still required, such as being able to show that the method is quantitative in capturing distinct sirtuins available in a reaction mixture, which would allow for isoform quantitation. Improvements could include use of a more efficient conjugation strategy, such as a clickable alkyne/azide pairing which would form a stable bond in the conjugate, thus improving quantitative recovery. The peptide could also be made to be crosslinkable which could make the technology cell permanent and more sirtuin specific. We anticipate that this technology could allow increased understanding of sirtuin activities in cells and could provide novel insights into enzymatic activity, regulation and how sirtuin levels and activities differ in tissues, in various physiological states and in pathologies. The isolation procedure can also be potentially helpful to identify unique splice variants or novelties such as post-translational modifications.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by R01 DK 73466 and Anthony A. Sauve is an Ellison Medical Foundation New Scholar (2007).

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary information (ESI) available: Detailed experimentals of enzyme production and kinetic assays, sirtuin capture assays, synthetic procedures and 1H and 13C NMR data. See DOI: 10.1039/c0ob00774a

References

- 1.Haigis MC, Guarente LP. Genes Dev. 2006;20:2913–2921. doi: 10.1101/gad.1467506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vaziri H, Dessain SK, Ng Eaton E, Imai SI, Frye RA, Pandita TK, Guarente L, Weinberg RA. Cell. 2001;107:149–159. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00527-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chua KF, Mostoslavsky R, Lombard DB, Pang WW, Saito S, Franco S, Kaushal D, Cheng HL, Fischer MR, Stokes N, Murphy MM, Appella E, Alt FW. Cell Metab. 2005;2:67–76. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brunet A, Sweeney LB, Sturgill JF, Chua KF, Greer PL, Lin Y, Tran H, Ross SE, Mostoslavsky R, Cohen HY, Hu LS, Cheng HL, Jedrychowski MP, Gygi SP, Sinclair DA, Alt FW, Greenberg ME. Science. 2004;303:2011–2015. doi: 10.1126/science.1094637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lombard DB, Chua KF, Mostoslavsky R, Franco S, Gostissa M, Alt FW. Cell. 2005;120:497–512. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schwer B, Bunkenborg J, Verdin RO, Andersen JS, Verdin E. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2006;103:10224–10229. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603968103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nakagawa T, Lomb DJ, Haigis MC, Guarente L. Cell. 2009;137:560–570. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Michishita E, Park JY, Burneskis JM, Barrett JC, Horikawa I. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2005;16:4623–4635. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-01-0033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang JY, Hirschey MD, Shimazu T, Ho L, Verdin E. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1804:1645–1651. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2009.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vaquero A, Scher MB, Lee DH, Sutton A, Cheng HL, Alt FW, Serrano L, Sternglanz R, Reinberg D. Genes Dev. 2006;20:1256–1261. doi: 10.1101/gad.1412706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen D, Bruno J, Easlon E, Lin SJ, Cheng HL, Alt FW, Guarente L. Genes Dev. 2008;22:1753–1757. doi: 10.1101/gad.1650608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fatkins DG, Monnot AD, Zheng W. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2006;16:3651–3656. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.04.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hawse WF, Hoff KG, Fatkins DG, Daines A, Zubkova OV, Schramm VL, Zheng W, Wolberger C. Structure. 2008;16:1368–1377. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2008.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jin L, Wei W, Jiang Y, Peng H, Cai J, Mao C, Dai H, Choy W, Bemis JE, Jirousek MR, Milne JC, Westphal CH, Perni RB. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:24394–24405. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.014928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith BC, Denu JM. Biochemistry. 2007;46:14478–14486. doi: 10.1021/bi7013294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sauve AA, Celic I, Avalos J, Deng H, Boeke JD, Schramm VL. Biochemistry. 2001;40:15456–15463. doi: 10.1021/bi011858j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sauve AA, Wolberger C, Schramm VL, Boeke JD. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2006;75:435–465. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.74.082803.133500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Adam GC, Cravatt BF, Sorensen EJ. Chem. Biol. 2001;8:81–95. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(00)90060-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kidd D, Liu Y, Cravatt BF. Biochemistry. 2001;40:4005–4015. doi: 10.1021/bi002579j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu Y, Patricelli MP, Cravatt BF. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1999;96:14694–14699. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.26.14694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fatkins DG, Zheng W. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2008;9:1–11. doi: 10.3390/ijms9010001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hoff KG, Avalos JL, Sens K, Wolberger C. Structure. 2006;14:1231–1240. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2006.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Allart B, Lehtolainen P, Yla-Herttuala S, Martin JF, Selwood DL. Bioconjugate Chem. 2003;14:187–194. doi: 10.1021/bc0255992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nauman DA, Bertozzi CR. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2001;1568:147–154. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(01)00211-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Howarth M, Ting AY. Nat. Protoc. 2008;3:534–545. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jacobs CL, Yarema KJ, Mahal LK, Nauman DA, Charters NW, Bertozzi CR. Methods Enzymol. 2000;327:260–275. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(00)27282-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sauve AA. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1804:1591–1603. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2010.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.