Abstract

Human embryonic stem cells (hESC) require a balance of growth factors and signaling molecules to proliferate and retain pluripotency. Conditioned medium (CM) from a human embryonic germ-cell-derived cell culture, SDEC, was observed to support the growth of hESC on type I collagen (COL I) and on Matrigel (MAT) biomatricies. After 1 month, the population doubling of hESC grown in SDEC CM on COL I was equivalent to that of hESC grown in mouse embryonic fibroblast (MEF) CM on MAT. hESC grown in SDEC CM on COL I expressed OCT4, NANOG, SSEA-4, alkaline phosphatase (AP), and TRA-1-60; retained a normal karyotype; and were capable of forming teratomas. DNA microarray analysis was used to compare the transcriptional profiles of SDEC and the less supportive WI38 and Detroit 551 human cell lines. The mRNA level of secreted frizzled-related protein (sFRP-1), a known antagonist of the WNT/β-catenin signaling pathway, was significantly reduced in SDEC as compared with the other 2 cell lines, whereas the mRNA levels of prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2 (PTGS2 or COX-2) and prostaglandin I2 synthase (PGIS), two prostaglandin biosynthesis genes, were significantly increased in SDEC. The level of sFRP-1 protein was significantly reduced, and levels of 2 prostaglandins that are downstream products of PTGS2 and PGIS, prostaglandin E2 and 6-keto-prostaglandin F1α, were significantly elevated in SDEC CM compared with WI38, Detroit 551, and MEF CM. Further, addition of purified sFRP-1 to SDEC CM reduced the proliferation of hESC grown on COL I as well as MAT in a dose-dependent manner.

Introduction

Therapies developed using human embryonic stem cells (hESC) have the potential to transform the treatment for a wide variety of diseases [1], including Parkinson's [2], diabetes [3–6], and heart disease [7–9]. These cells could also provide a source of cellular therapies for the replacement of damaged or destroyed tissues [10–15], and tissues derived from hESC could be used in drug discovery and toxicology studies [16,17]. The success of these applications, however, depends on our capacity to provide an adequate supply of hESC for research and development purposes. Critical to this goal is the specification of well-defined and reproducible culture conditions that will allow for large-scale expansion of these cells while providing efficient self-renewal, maintenance of pluripotency, and chromosomal stability.

Currently, hESC are often cocultured with feeder layers of mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEF). Cells grown in this manner are not ideal for transplantation into humans due to the risk of xenogenic-based rejection by the immune system [18] as well as the potential for cross-species transfer of viruses or pathogens [19]. MEF feeder layers can be replaced with human-derived cell lines to avoid hESC contact with murine cells, but the presence of additional cell lines in hESC culture inevitably contributes to variability and increased cost during the expansion and scale-up of stem cells [19–21]. As a result, direct coculture has been replaced by medium conditioning, where hESC are grown on an acellular support matrix in the medium that has been conditioned by a separate, supporting cell line [19,20,22,23].

hESC grown in feeder-free culture require a solid growth matrix on which to proliferate, the most common being Matrigel™ (MAT), a complex basement membrane extract derived from Engelbreth-Holm-Swarm mouse sarcoma whose composition is not well defined [22,24,25]. MAT is used because most hESC do not grow well on more defined matrices like fibronectin, laminin, or collagen [26–28]. A simple, completely defined matrix that could support hESC growth and maintenance of pluripotency would provide significant advantages over the use of MAT or feeder layers in terms of reproducibility, scale-up, cost, and applicability to human therapies [29]. Type I collagen (COL I) offers significant potential as a hESC growth biomatrix because it is well defined, widely available, and FDA approved for several applications [30–36].

There have been several attempts to eliminate the undefined and animal-derived elements in both the hESC liquid medium and solid growth matrix. In one study, replacing the undefined MAT matrix required a complex and expensive combinatorial matrix composed of multiple constituents, including collagen IV, fibronectin, laminin, and vitronectin. The inconvenience in using such a complex matrix was noted as a drawback to the system, as were its expense and its potential as a source of contamination [25,29]. This led the authors to conclude that development of the support matrix is one area of stem cell culture that requires improvement [25]. Even with this complex matrix, the hESC eventually became karyotypically abnormal, a fact that may be due, at least in part, to the absence of a proper balance of growth factors [37]. In a more recent study, Brafman et al. utilized an array-based technology to screen hundreds of hESC growth microenvironments composed of various extracellular matrix proteins and signaling molecules. They found that optimal hESC growth conditions required a combination of collagen I, collagen IV, fibronectin, and laminin [38].

Xu et al. observed that MEF-conditioned media (CM) supported undifferentiated hESC growth on MAT or laminin surfaces, but that hESC underwent spontaneous differentiation when added to a fibronectin or type IV collagen matrix [28]. Laminin and fibronectin, along with defined supplements, can sometimes support stem cell growth, but these matrices may not be as effective as growth on MAT or direct coculture with MEF [20,28,39–41]. One study found that fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF2) and Noggin would help support hESC growth on MAT, but the use of a laminin matrix was subject to significant batch-to-batch variability and an inability to support clonal hESC growth [20,39]. Subsequent work done using similar growth conditions found that another hESC line remained undifferentiated on MAT for up to 15 passages but only for 3 confirmed passages on laminin [20]. Amit et al. [40] were able to maintain hESC on a fibronectin matrix using transforming growth factor β, FGF2, and leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF) along with the addition of 15% serum replacement [40]. However, growth on fibronectin exhibited lower growth rates, reduced cloning efficiency, and a higher rate of spontaneous differentiation compared with growth on MEF [20,40]. Recently, another group achieved hESC growth on a vitronectin matrix using a chemically defined media formulation [42]. These more defined culture systems often require CM, serum replacement products, added growth factors, or complex matrix components. Due to the difficulties involved in using more defined matrices, the great majority of studies, including the derivation of embryonic stem-cell-like iPS cells from adult fibroblasts, utilize the undefined MAT matrix along with MEF CM to maintain the cells in an undifferentiated state [26,27].

In this study we investigate the ability of CM from a human embryonic germ-cell-derived cell culture, SDEC [43], to support the growth of hESC on both MAT and COL I. We screened 15 different embryonic germ-cell-derived cultures [43] and SDEC was found to be the most supportive of hESC growth (unpublished data). To begin to identify the factors that allow CM from SDEC to support hESC growth on COL I and to obtain insights into the roles that these factors play in maintaining robust hESC self-renewal, we compared the transcriptional profiles of SDEC and two other nonsupportive feeder cell lines. Human fetal foreskin fibroblast line Detroit 551 and human fetal lung fibroblast line WI38 were previously reported to be supportive and nonsupportive, respectively, of hESC growth when used as direct feeder layers [44]; however, we found that CM from neither cell line could support long-term hESC growth.

Microarray data indicated that secreted frizzled-related protein (sFRP-1) expression was significantly downregulated in SDEC compared with the other 2 cell lines. sFRP-1 is a known antagonist of the WNT/β-catenin signaling pathway, which has been shown to play a role in maintaining hESC proliferation and pluripotency. Two genes in the prostaglandin synthesis pathway, prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2 (PTGS2) and prostaglandin I2 synthase (PGIS), were significantly upregulated in the SDEC culture, suggesting that this pathway is activated in SDEC. The microarray data were confirmed by quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) as well as western blot analysis. To examine prostaglandin biosynthesis further, the levels of prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) and 6-keto-prostaglandin F1α (6-k-PGF1α) were monitored in SDEC, WI38, Detroit 551, and MEF CM. The possible role of sFRP-1 in affecting stem cell growth was also investigated further. SDEC medium was supplemented with varying concentrations of purified sFRP-1 and the effect on hESC proliferation was monitored. Analysis of the factors present in SDEC CM may aid in the development of a defined cell culture system that permits hESC growth and expansion in a chemically defined liquid medium on a simple, fully defined matrix such as COL I.

Materials and Methods

Feeder cell derivation and culture

The SDEC cell culture was derived from human embryonic germ cells as described [43]. Briefly, cells were derived and maintained on a matrix of type I bovine collagen (10 μg/cm2; Collaborative Biomedical Products) in EGM-2 MV medium (Clonetics) supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum, hydrocortisone, human basic FGF, human vascular endothelial growth factor, insulin-like growth factor I, ascorbic acid, human epidermal growth factor, gentamycin, and amphotericin. All experiments were carried out using medium conditioned by SDEC cells on passage 8 through 10. Detroit 551 (ATCC, CCL-110) and WI38 (ATCC, CCL-75) cell lines were obtained from ATCC. Detroit 551, WI38, and MEF (strain CF1; Chemicon) were maintained at 37°C, 5% CO2, 95% humidity in DMEM (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Hyclone), 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, and 2 mM L-glutamine.

Preparation of CM

Feeder cells were grown to confluence in their respective growth media, and then medium was changed to human embryonic stem cell (huES) medium [45] consisting of Knockout DMEM (Invitrogen), 10% knockout serum replacement (Invitrogen), 10% Plasmanate® (Bayer), 2 mM L-glutamine (Invitrogen), 0.1 mM nonessential amino acids (Invitrogen), 1 mM sodium pyruvate (Invitrogen), 0.1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, and 8 ng/mL FGF2 (R&D systems). After 24 h the CM was collected, filtered over a 0.22 μm filter, and stored at −80°C for up to 2 months. CM harvesting was repeated for up to 2 weeks or until feeder layers degraded and pooled before use to ensure uniformity. CM was supplemented with an additional 8 ng/mL FGF2 immediately before use.

hESC culture

For long-term maintenance, hESC lines H1 and H9 (WiCell) were maintained in huES medium [45] on irradiated MEF and passaged with 1 mg/mL collagenase. Before initiation of CM experiments, hESC lines were passaged 3 times using 0.05% trypsin–ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) and plated on growth-factor-reduced MAT (BD Biosciences)–coated plates (1:20 dilution in base media) in the presence of MEF-conditioned huES medium as described [28]. For routine passage, cells were digested with 0.05% trypsin-EDTA for 5 min at 37°C, and then trypsin neutralizing solution was added and cells were triturated gently to form small clumps of cells. Cells were centrifuged at 100 g for 5 min and resuspended in media. For cell counts, the same procedure was followed except that cells were triturated until a single-cell suspension was formed. In between passages, the medium was replaced with fresh CM every day and 8 ng/mL FGF2 was added immediately before use. For CM experiments, hESC lines were passaged 1:3 every 3–5 days using 0.05% trypsin-EDTA and plated on dishes coated with either growth-factor-reduced MAT or COL I. Equal numbers of cells were plated each passage. Cells were counted on a Nucleocounter (New Brunswick Scientific) on triplicate wells. Population doubling (PD) was calculated as 3.32 × (log10 cell countfinal − log10 cell countstarting). Statistical significance was calculated using the heteroscedastic Student's t-test.

Cell proliferation assay

hESC previously passaged on MAT were plated at 5 × 103 cells/well in a 96-well dish coated with COL I or MAT in SDEC CM. After 24 h, SDEC CM was supplemented with various concentrations of sFRP-1 (R&D Systems) and used to replace the cell medium daily. Proliferation data are reported as a mean of 4 biological replicate cultures ± standard error for each dosage. Control wells were supplemented with sFRP-1 resuspension buffer [phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) with 0.1% bovine serum albumin (BSA)]. After a total of 3 days, CellTiter 96 AQueous (Promega) MTS reagent was added, the plate was incubated for 1 h, and the optical density at 490 nm was determined. A standard curve of cell number per well was done in parallel to insure that readings were within the linear range of the assay. Statistical significance was calculated directly from the optical density data using the heteroscedastic Student's t-test.

Immunocytochemistry

hESC were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 5 min at room temperature, blocked in 5% donkey serum and 1% BSA for 30 min at room temperature, and then incubated with antibodies to SSEA-4 (Chemicon), OCT4 (Chemicon), Nanog (Chemicon), or Tra-1-60 (Chemicon). Staining for OCT4 and Nanog were carried out in the presence of 0.1% Triton X-100. Secondary antibodies were donkey anti-mouse conjugated to either Alexafluor-488 or Alexafluor-594 (Invitrogen). Cells were counterstained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) to detect the nuclei. The percentage of cells expressing each marker was determined by viewing 5 randomly acquired fields with a total of >1,000 nuclei per well using a microscope-equipped frame capturing software. Each percentage was calculated by dividing the number of cells with positive staining for the marker by the total number of cells (determined via DAPI staining). Data are reported as a mean of triplicate wells ± standard error. Statistical significance was calculated using the heteroscedastic Student's t-test.

Karyotype analysis

hESC prepared for cytogenetic analysis were incubated in growth media with 0.1 mg/mL of Colcemid for 1 h, washed in PBS, trypsinized, resuspended in 0.075 M KCl, and incubated for 20 min at 37°C, and then fixed in 3:1 methanol/acetic acid. A minimum of 5 metaphase spreads were analyzed manually by Johns Hopkins scientists with cytogenetics expertise.

Teratoma formation

hESC were passaged in SDEC CM on COL I for at least 20 PD over a 1-month period, and then ∼3 × 106 hESC were injected into the calf muscle of NOD/SCID mice. After 1 month, tumors were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS and then processed for paraffin embedding. Sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin.

RNA isolation and DNA microarray analysis

Total RNA was isolated from confluent 10 cm dishes of SDEC, WI38, and Detroit 551 cells (maintained in huES medium for at least 48 h) using the RNeasy Total RNA isolation kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Three biological replicate dishes of each cell type were used. Using 5 μg of total RNA, cDNA was synthesized using the GeneChip® One-Cycle cDNA Synthesis Kit (manufactured by Invitrogen for Affymetrix). The cDNA was used as a template to synthesize biotin-labeled cRNA using the GeneChip® IVT Labeling Kit (Affymetrix). Hybridization to the Human Genome U133 Plus 2.0 DNA microarrays (Affymetrix), washing, and scanning were completed according to the manufacturer's instructions. The program dChip [46,47] was used to normalize and compare the data from the 9 samples with minimal criteria set as ± fold change of 2, a P value of 0.02, and a signal presence percentage of 30%. Fold change values were recalculated with respect to the supportive feeder layer, SDEC.

Quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA isolated from SDEC, WI38, and Detroit 551 was reverse transcribed into cDNA using oligo(dT) primers and Moloney Murine Leukemia Virus Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen). Quantitative RT-PCR was carried out using TaqMan reagents and primer/probe sets (Applied Biosystems) for sFRP-1 (Hs00610060_m1) and PTGS2 (Hs01573471_m1) using a 7900HT sequence detector (Applied Biosystems), standard cycling parameters, and the Ct quantification method. Levels of cyclophilin A (PPIA; Applied Biosystems Endogenous Control) were used to normalize expression data. Standard curves were created by serial dilution of pooled samples. Data are reported as a mean of triplicate cultures ± standard error. Statistical significance was calculated using the heteroscedastic Student's t-test.

Western blot analysis of PTGS2

Confluent dishes of SDEC, WI38, and Detroit 551 cells were used to condition huES medium for 24 h. The CM was collected and cell cytoplasmic lysates were obtained using the NE-PER cell lysis kit (Pierce Scientific). The total protein in the lysate was quantified using the BCA™ Protein Assay Kit (Pierce). Equal amounts (20–30 μg) of protein were separated on 4%–12% NuPAGE Bis-Tris gels (Invitrogen) and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Membranes were blocked in 5% nonfat dried milk in Tris-buffered saline supplemented with 0.1% Tween-20 (TTBS), and then incubated with antibodies to PTGS2 (Calbiochem) or β-actin (Abcam) in blocking buffer and observed by using chemiluminescence (Supersignal West Pico; Pierce).

Analysis of sFRP-1 in CM

sFRP-1 was purified as previously described [48]. Briefly, frozen CM from SDEC, Detroit 551, WI38, and MEF cells were thawed, precleared by centrifugation, and loaded on separate 1 mL HiTrap Heparin HP columns (GE Healthcare) that had been equilibrated with 0.05 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) containing 0.2 M NaCl. After washing the columns with 30 mL of equilibration buffer, retained protein was eluted with 10 mL each of 0.05 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) solutions containing increasing concentrations of NaCl (0.3, 0.7, 1.0, and 1.2 M). During the elution steps, 1 mL fractions were collected and aliquots of each fraction (24 μL) were resolved on 10% polyacrylamide–sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) Tris-HCl gels (Criterion Precast Gel; Bio-Rad) under reducing conditions. Proteins were transferred to Immobilon-P membranes (Millipore) that were blocked in 5% nonfat dried milk dissolved in TTBS. Membranes were then incubated with 2.5 μg/mL of an sFRP-1 N-terminal peptide antibody [49] in blocking buffer, followed by donkey anti-rabbit IgG (1:10,000; GE Healthcare), and the sFRP-1 protein was observed with chemiluminescent reagents (Supersignal West Femto; Pierce). Subsequently, aliquots of the peak fractions from each cell type were pooled, resolved by SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and immunoblotted alongside corresponding pools from the other cell types. Varying amounts of recombinant human sFRP-1 [48] were included in all blots to facilitate quantitative analysis of sFRP-1 concentration.

Analysis of prostaglandins in CM

Levels of 6-k-PGF1α (Oxford Biomedical Research) and PGE2 (Cayman Chemical) in CM were determined by commercially prepared enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) from CM collected from 3 independent cultures of each cell type. Data are reported as a mean of triplicate wells ± standard error. Significance was determined by one-way analysis of variance with Bonferroni–Holm post hoc testing.

Results

SDEC CM supports hESC maintenance and proliferation

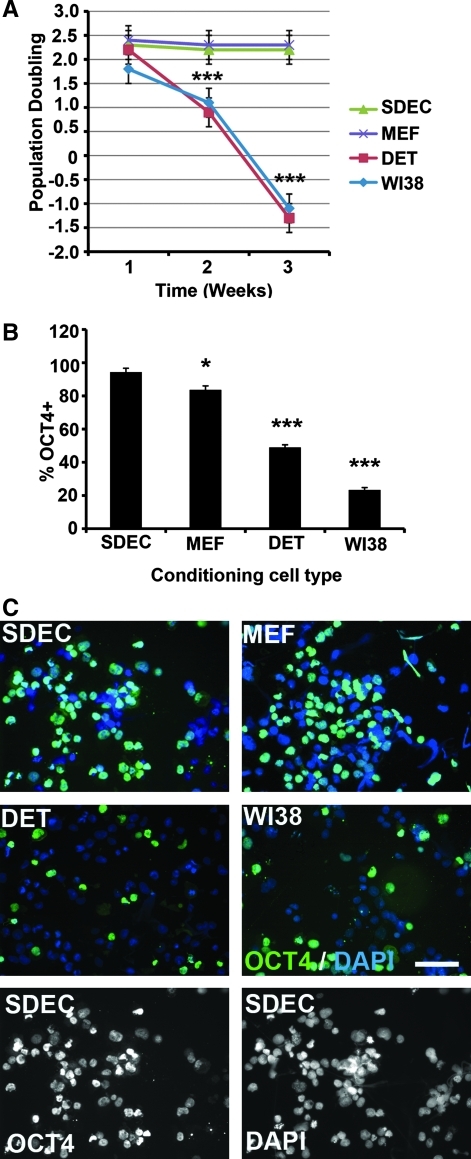

CM from the human cell types SDEC, WI38, and Detroit 551 were compared with MEF CM for their capacity to support hESC self-renewal and pluripotency over a 3-week period (5 passages) when plated on MAT-coated plates. There were no significant differences in hESC line H1 PD during the first week of growth in the various CM (Fig. 1A). However, by week 2, H1 cells proliferated significantly less in WI38 (PD = 1.1) or Detroit 551 (PD = 0.9) CM than in SDEC (PD = 2.2) or MEF (PD = 2.3) CM. By week 3, hESC numbers decreased in WI38 (PD = −1.1) and Detroit 551 (PD = −1.3) CM while maintaining the week 2 PD in SDEC and MEF CM. There was no significant difference between PD in SDEC and MEF CM (Fig. 1A). After the third week of growth under these conditions, hESC were immunostained to determine the percentage of cells expressing OCT4. There was a small but significant difference (P < 0.05) between the percentage of OCT4+ hESC grown in SDEC CM (94 ± 2.3) compared with MEF CM (84 ± 2.4) (Fig. 1B). However, there was a large significant difference (P < 0.001) between the percentage of OCT4+ cells in SDEC and either Detroit 551 (49 ± 1.5) or WI38 (23 ± 1.5) CM. Representative OCT4 immunostains of hESC grown in each of the CM types are shown in Fig. 1C. The experiment was terminated after 3 weeks because of insufficient stem cell numbers in the WI38 and Detroit 551 CM treatments. The PD and OCT4 protein expression data suggest that SDEC CM is capable of supporting hESC proliferation and maintenance on MAT at least as well as MEF CM. In contrast, WI38 and Detroit 551 CM are not capable of maintaining long-term hESC growth. These trends were observed in multiple replicate experiments and similar results were found using another hESC line, H9 (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

hESC proliferation and OCT4 expression for cells grown in SDEC-, MEF-, WI38-, and DET-conditioned medium on Matrigel. (A) Population doubling (mean ± SE, N = 3) of hESC over 3 weeks. (B) Percentage of OCT4-positive cells (mean ± SE, N = 3) after 3 weeks. (C) Immunofluorescent staining of hESC with OCT4 after 3 weeks. Nuclei stained with DAPI. Scale bar = 50 μm (magnification × 400). Significance: *P < 0.05 and ***P < 0.001. DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; DET, Detroit 551; hESC, human embryonic stem cells; MEF, mouse embryonic fibroblast; SE, standard error.

SDEC CM allows for hESC growth on COL I

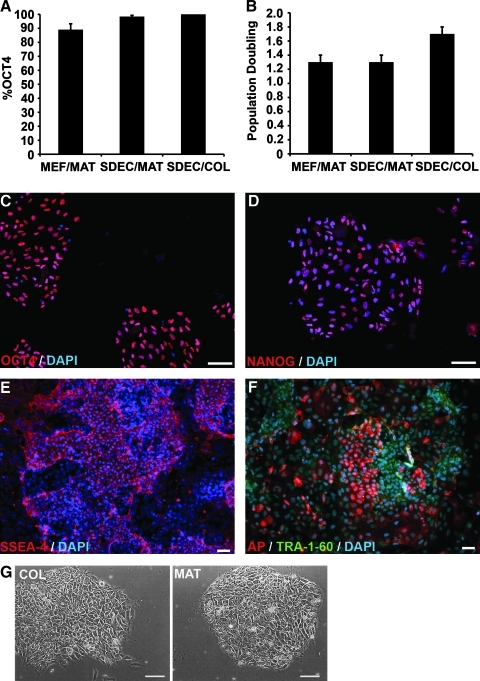

To investigate the ability of SDEC CM to support hESC growth and maintain hESC pluripotency on different growth matrices, we compared H1 hESC grown in either SDEC or MEF CM on both MAT and COL I over a 1-month period (at least 20 PD). There were no statistically significant differences between the percentage of cells expressing OCT4 for MEF CM on MAT (89% ± 4.2), SDEC CM on MAT (98.4 % ± 0.9), and SDEC CM on COL I (100%) (Fig. 2A). The PD per week after 1 month in MEF or SDEC CM on MAT was 1.3, whereas the PD for the SDEC CM on COL I was 1.7, but this difference was not statistically significant (Fig. 2B). Unlike SDEC CM, MEF CM was unable to support the growth of hESC on COL I (data not shown). After 1 month, hESC growing in SDEC CM on COL I also expressed pluripotency markers Nanog, SSEA-4, AP, and TRA-1-60 (Fig. 2C–F). The hESC colonies grown on COL I resembled those grown on MAT, with typical cellular morphology and clearly defined colony borders (Fig. 2G). These general results were seen in 4 replica experiments and similar findings were also observed using hESC line H9 (data not shown). At the end of this 1-month period, both hESC lines retained a normal karyotype (data not shown) and were capable of forming teratomas containing differentiated tissues from all 3 embryonic germ layers following transplantation into immunocompromised mice (Fig. 3).

FIG. 2.

hESC proliferation and expression of pluripotency markers for cells grown in SDEC or MEF CM on MAT or COL. (A) Percentage of OCT4-positive cells (mean ± SE, N = 4) after 1 month. (B) Population doubling (mean ± SE, N = 3) of hESC at the end of 1 month. (C–F) Immunofluorescent staining of hESC grown in SDEC CM on COL after 1 month. Nuclei stained with DAPI. (C) OCT4, (D) NANOG, (E) SSEA-4, and (F) AP and TRA-1-60. (G) Phase microscopy of hESC colonies growing on COL and MAT. Scale bars = 50 μm (magnification × 400 for C, D, and G; magnification × 200 for E and F). AP, alkaline phosphatase; CM, conditioned medium; DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; hESC, human embryonic stem cells; MAT, Matrigel; MEF, mouse embryonic fibroblast; SE, standard error.

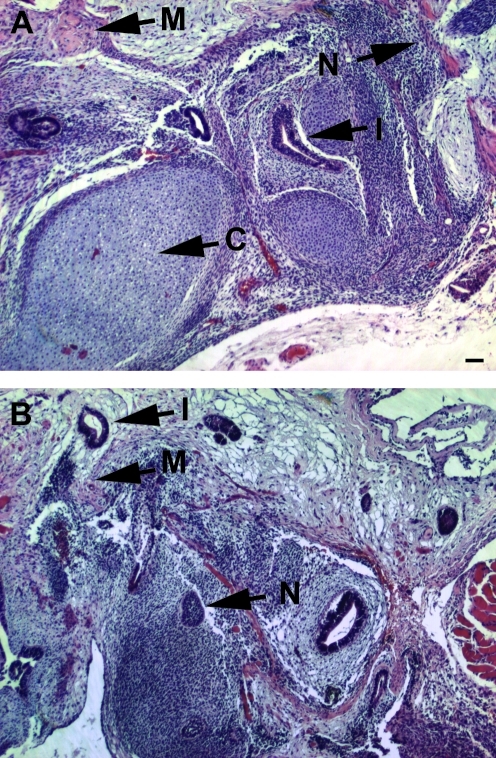

FIG. 3.

Hematoxylin and eosin–stained sections of teratomas formed following transplantation of hESC into NOD/SCID mice. hESC lines (A) H1 and (B) H9. Tissue features marked: M, muscle; N, neuroectoderm; I, intestinal epithelia; C, cartilage. Scale bars = 100 μm (magnification × 100). hESC, human embryonic stem cells.

Transcriptional profiling of supportive and nonsupportive feeder cells

On the basis of our finding that SDEC CM is supportive of hESC growth and pluripotency, we compared the transcriptional profile of this cell culture to those of the nonsupportive human feeder cell lines, WI38 and Detroit 551, using DNA microarray analysis. MEF cells were not included in this comparison due to their non-human origin. The microarray data have been deposited in NCBI's Gene Expression Omnibus [50] and is accessible through GEO Series accession No. GSE15400 (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc = GSE15400). For our initial analysis of these data, we calculated the fold change in gene expression level with respect to the SDEC culture. We then ranked these values and looked at the 20 genes that were the most highly overexpressed by the nonsupportive cell lines compared with SDEC (Table 1) and the 20 genes that were the most highly overexpressed by SDEC compared with the nonsupportive lines (Table 2). sFRP-1 was the most highly overexpressed gene in WI38 and Detroit 551 compared with SDEC. Conversely, 2 enzymes in the prostaglandin synthetic pathway, PTGS2 and PGIS, were both highly overexpressed by SDEC compared with the nonsupportive feeder lines. Interestingly, the gene for LIF was also upregulated in SDEC, although unlike in mouse embryonic stem cell culture, this protein is not sufficient to prevent differentiation in hESC culture [51,52].

Table 1.

Top Twenty Genes Overexpressed by the Nonsupportive Feeder Layers

| |

|

Fold difference |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Gene | Accession No. | Detroit 551/SDEC | WI38/SDEC |

| Secreted frizzled-related protein 1 | AI332407 | 55.35 | 153.14 |

| SIX homeobox 1 | NM_005982 | 13.47 | 81.76 |

| Hepatocyte growth factor | X16323 | 22.90 | 62.37 |

| Matrix metallopeptidase 3 | NM_002422 | 58.88 | 13.44 |

| Pentraxin-related gene, rapidly induced by IL-1 beta | NM_002852 | 16.12 | 44.43 |

| Fibulin 1 | NM_006486 | 45.72 | 12.31 |

| Endothelin receptor type A | NM_001957 | 46.85 | 7.91 |

| Cell adhesion molecule 1 | NM_014333 | 11.52 | 31.76 |

| Forkhead box F2 | NM_001452 | 11.57 | 29.07 |

| Sema domain, 7 thrombospondin repeats, TM and short cytoplasmic domain (semaphorin) 5A | NM_003966 | 30.36 | 9.06 |

| Paired-related homeobox 1 | AA775472 | 28.41 | 10.80 |

| PR domain containing 1, with ZNF domain | AI692659 | 28.58 | 7.98 |

| Homeobox B5 | NM_002147 | 7.94 | 21.07 |

| Hephaestin | NM_014799 | 17.84 | 5.14 |

| Plasminogen activator, urokinase | NM_002658 | 6.67 | 14.96 |

| Forkhead box F1 | NM_001451 | 5.87 | 14.49 |

| Syndecan 1 | NM_002997 | 14.37 | 3.89 |

| Sema domain, immunoglobulin domain (Ig), short basic domain, secreted (semaphorin) 3A | NM_006080 | 3.78 | 13.43 |

| Runt-related transcription factor 1; translocated to, 1 (cyclin D-related) | NM_004349 | 13.08 | 3.55 |

| Suppressor of cytokine signaling 2 | NM_003877 | 3.53 | 12.21 |

Table 2.

Top Twenty Genes Overexpressed by the Supportive Feeder Layer

| |

|

Fold difference |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Gene | Accession No. | SDEC/Detroit 551 | SDEC/WI38 |

| Prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase | NM_000963 | 26.37 | 230.22 |

| Adhesion molecule with Ig-like domain | AC004010 | 27.10 | 180.58 |

| Prostaglandin I2 (prostacyclin) synthase | NM_000961 | 24.09 | 161.50 |

| Cytochrome P450, family 1, subfamily B, polypeptide 1 | AU144855 | 13.49 | 151.47 |

| Serglycin | NM_002727 | 24.26 | 122.90 |

| Interleukin 8 | AF043337 | 21.75 | 87.01 |

| Protocadherin 10 | AI640307 | 7.66 | 94.38 |

| ADAM metallopeptidase domain 12 | NM_003474 | 5.18 | 60.66 |

| CDNA FLJ44429 | AI088063 | 6.73 | 52.08 |

| Ras-related associated with diabetes | NM_004165 | 39.78 | 8.38 |

| Serum/glucocorticoid regulated kinase | NM_005627 | 11.58 | 31.28 |

| Chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2 | S69738 | 9.45 | 27.56 |

| Cadherin 2, type 1, N-cadherin | M34064 | 8.47 | 27.39 |

| Tumor necrosis factor superfamily, member 4 | NM_003326 | 24.37 | 7.15 |

| Dipeptiyl-peptidase 4 (CD26) | M74777 | 6.38 | 24.38 |

| Leukemia inhibitory factor | NM_002309 | 21.17 | 5.50 |

| Coiled-coil domain containing 80 | AA570507 | 5.06 | 21.35 |

| HEG homolog 1 | AI148659 | 6.85 | 17.14 |

| Aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 family, member A3 | NM_000693 | 5.30 | 18.61 |

| Chromosome 3 ORF | AU157304 | 5.40 | 13.94 |

Validation of microarray results

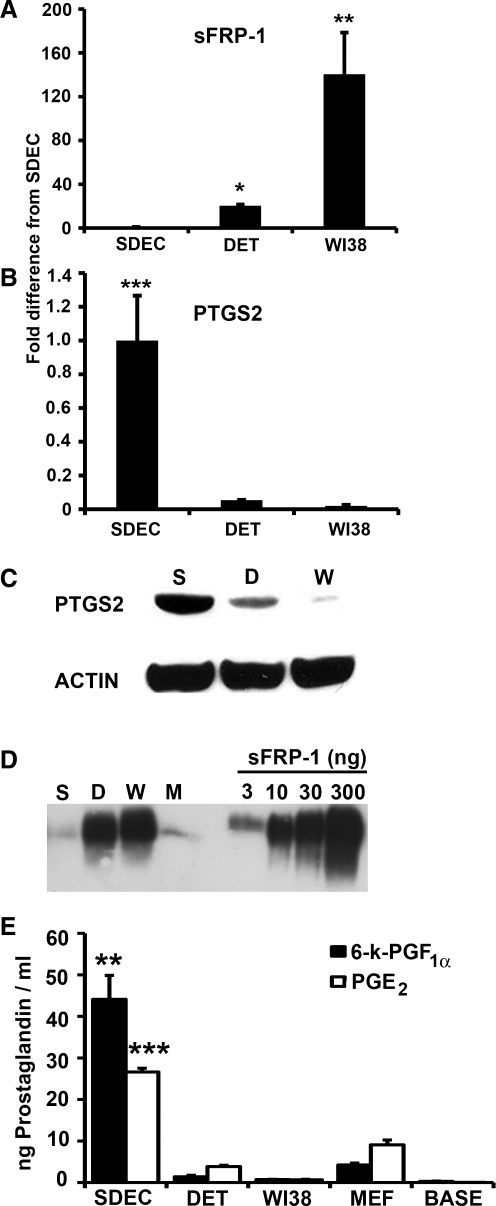

To validate differential expression of sFRP-1 and PTGS2 in SDEC compared with WI38 and Detroit 551, we used quantitative RT-PCR. In agreement with our microarray results, the mRNA level of sFRP-1 in WI38 cells increased 140 ± 38-fold (P < 0.01) over the level detected in SDEC and sFRP-1 expression in Detroit 551 cells increased 20 ± 1.1-fold (P < 0.05) over the level in SDEC (Fig. 4A). Conversely, the PTGS2 mRNA level was significantly lower (P < 0.001) in Detroit 551 (18.6 ± 0.03-fold) and in WI38 (51.2 ± 0.4-fold) than in the SDEC cells (Fig. 4B). Thus, the quantitative RT-PCR data for these two genes correlate well with differences observed in the microarray data.

FIG. 4.

Expression of sFRP-1 and PTGS2 and prostaglandins by DET, WI38, and SDEC cell types. Quantitative RT-PCR was done to determine the fold difference in mRNA expression level (mean ± SE, N = 3) for (A) sFRP-1 and (B) PTGS2. mRNA levels were normalized using PPIA mRNA (housekeeping gene). Semiquantitative western blots were done on (C) intercellular PTGS2 (using β-actin to control for protein loading) and (D) sFRP-1 recovered from CM (180 mL from SDEC and DET, 150 mL from WI38). sFRP-1 recovered from MEF CM (180 mL) was also included in this western blot. The indicated amounts of recombinant human sFRP-1 were included for comparison. (E) Levels (mean ± SE, N = 3, ng/mL) of 6-k-PGF1α (black) and PGE2 (white) in CM from the 3 human cell types, MEF CM, and unconditioned human embryonic stem cells medium (BASE). Significance: **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001. CM, conditioned medium; DET, Detroit 551; MEF, mouse embryonic fibroblast; PGE2, prostaglandin E2, PTGS2, prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2; RT-PCR, reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction; sFRP-1, secreted frizzled-related protein; 6-k-PGF1α, 6-keto-prostaglandin F1α; SE, standard error.

Expression of sFRP-1 and PTGS2 proteins

To examine the expression levels of sFRP-1 and PTGS2 at the protein level, we carried out semiquantitative western blot analysis. The intracellular levels of PTGS2 in SDEC, WI38, and Detroit 551 cells were compared using cell cytoplasmic extracts. Equivalent amounts of total protein were used in each lane and β-actin was used as a loading control. As shown in Fig. 4C, SDEC expressed the most PTGS2, followed by Detroit 551, whereas the PTGS2 in WI38 was barely detectable.

To compare the amounts of sFRP-1 secreted into the CM by the 3 human cell types as well as MEF cells, we used heparin-Sepharose chromatography to purify sFRP-1 from similar quantities of CM from each cell type. sFRP-1 was recovered in the 1.0 M NaCl fractions, as previously reported [49]. Quantitative analysis of western blots indicated that the level of sFRP-1 in the WI38 CM was greater than the level in Detroit 551 CM, and that the CM from both of these lines contained 10–20 times more sFRP-1 than SDEC or MEF CM (Fig. 4D). In agreement with our microarray data, SDEC expressed significantly less sFRP-1 and significantly more PTGS2 than the 2 less-supportive human feeder cell lines.

Levels of prostaglandins in CM

To determine whether the expression level of the intracellular protein PTGS2 would affect the levels of its soluble downstream products, PGE2 and prostacyclin (PGI2), in the CM, we performed ELISAs to probe the concentrations of these compounds in SDEC, Detroit 551, WI38, and MEF CM. PGI2 is unstable (t1/2 = 2–3 min.), so its stable hydrolysis product, 6-k-PGF1α, is typically monitored. The mean concentrations (N = 3) of 6-k-PGF1α were 44 ± 6, 1.4 ± 0.4, 0.7 ± 0.1, and 4.3 ± 0.4 ng/mL for SDEC, Detroit 551, WI38, and MEF CM, respectively. Levels of PGE2 were 26.6 ± 0.9, 3.9 ± 0.3, 0.7 ± 0.1, and 9.1 ± 1.2 ng/mL for SDEC, Detroit 551, WI38, and MEF CM, respectively (Fig. 4E). These data indicate that the levels of both PGE2 and 6-k-PGF1α were significantly increased in the supportive SDEC CM compared with both the nonsupportive CM and MEF CM.

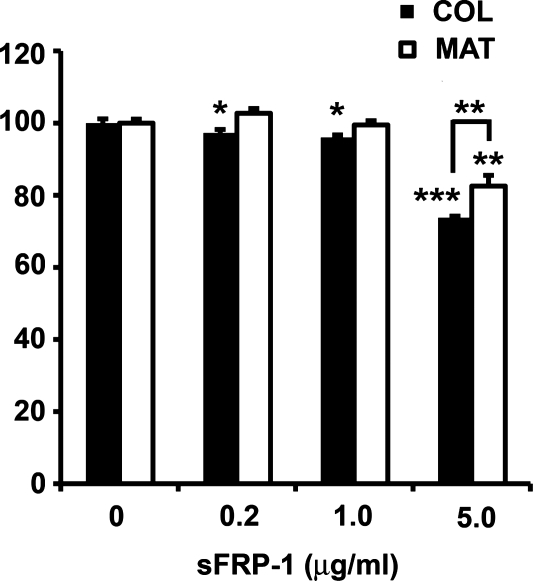

Effect of sFRP-1 on hESC proliferation

A cell proliferation assay was performed to determine the impact of exogenous sFRP-1 on hESC line H9 growth on different biomatrices. Cells grown in SDEC CM on either MAT or COL I were exposed to different concentrations of sFRP-1 for 3 days, and then hESC proliferation was measured. After the 3-day exposure to SDEC CM supplemented with 5 μg/mL sFRP-1, the highest concentration tested, there was a significant reduction in the number of cells growing on MAT (82% ± 1.1% of control, P < 0.01) or on COL I (74% ± 1.2% of control, P < 0.001) compared with CM without any added sFRP-1 (Fig. 5). Further, there were significantly fewer cells on COL I than on MAT (P < 0.01). At sFRP-1 concentrations of 1.0 and 0.2 μg/mL, there was a small but significant difference (P < 0.05) between the number of hESC growing in the presence versus absence of sFRP-1 but only for cells growing on COL I. Similar results were seen in replica experiments on hESC H1 cells (data not shown).

FIG. 5.

Cell proliferation assay of H9 human embryonic stem cells grown on COL or MAT matrices in SDEC-conditioned medium supplemented with various concentrations of sFRP-1. Proliferation of control (no added sFRP-1) was set to 100% and the percent of control proliferation (mean ± standard error, N = 4) for each sFRP-1 concentration is reported. Significance: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001. MAT, Matrigel; sFRP-1, secreted frizzled-related protein.

Discussion

Maintaining hESC in culture requires a complex mixture of soluble and extracellular matrix components. Current hESC culture techniques often involve hESC contact with medium components that are undefined or of animal origin, such as MEF, MAT, or CM, from feeder cell lines. Unfortunately, these incompletely defined culture conditions limit our ability to grow pluripotent hESC in a reproducible and scalable manner for both laboratory and clinical applications. There is significant interest in understanding the contributions of medium composition, growth matrix, and feeder cell line to overall hESC growth and pluripotency, both to understand the mechanisms and functional roles of these components in hESC self-renewal, and as a means of developing a more defined culture environment that would be suitable for future clinical phase expansion of hESC.

Significant progress has been made in developing more defined medium formulations and in eliminating undefined or xenogenic components such as animal serum and contamination by mitotically inactivated but viable feeder cells [39,40,53,54]. These defined medium formulations sometimes require conditioning by supporting cells, such as MEF [28,41] or human fibroblasts [20,39,55,56], for karyotypically stable long-term maintenance of hESC. Further, hESC growth in these CM often still requires the use of complex and poorly defined xenogenic biomatricies, such as MAT. In a step toward identifying a more defined hESC growth environment, we describe a human cell type, SDEC, that produces CM capable of maintaining hESC growth on a matrix of simple COL I. COL I is widely used in humans in health and beauty care applications [30–36]. SDEC is one example of a cell type generically termed embryoid body derived (EBD) [43]. EBD cells such as SDEC are capable of high rates of proliferation, have multilineage gene expression profiles, and have been used directly in cell transplantation studies [57–59]. The hESC grown in SDEC CM on MAT or COL I have equal or superior cell proliferation rates, maintenance of pluripotency, and karyotypic stability compared with hESC grown in MEF CM on MAT.

To begin to understand the complex nature of hESC supportive CM, we compared the transcriptional profiles of the highly supportive SDEC cell culture and 2 human fibroblast cell lines, WI38 and Detroit 551, which do not produce supportive CM. A large number of genes were differentially regulated across the 3 cell types, but in this study we chose to focus on 2 of the most highly differentially expressed genes: PTGS2 and sFRP-1.

The protein sFRP-1 is a secreted protein that is a known antagonist of the WNT/β-catenin signaling pathway [60]. In this pathway, WNT binds to frizzled protein (Fzd) and activates the pathway by disrupting a complex of inhibitor proteins (including axin, CKIα, GSK-3, and APC), resulting in the stabilization of β-catenin [61]. β-catenin can then enter the nucleus and interact with other proteins to promote transcription [61,62]. sFRP-1 contains a domain homologous to the cysteine-rich domain of Fzd and will bind to WNT, inhibiting WNT's interaction with Fzd and blocking activation of the β-catenin pathway [60]. This pathway is known to have a key role in stem cell proliferation and maintenance of pluripotency through activation of NANOG and other factors such as OCT4 [61,63–69], although increased WNT signaling has also been associated with hESC differentiation [70]. Thus, disruption of this pathway is a plausible mechanism for sFRP-1's inhibitory activity in our hESC growth assays. However, sFRP-1 also modulates other signaling pathways and is known to interact with matrix molecules and other receptors, so it remains possible that its effect on hESC growth could involve additional mechanisms [71,72].

Our data show high levels of sFRP-1 in the nonsupportive WI38 and Detroit 551 CM relative to the supportive SDEC and MEF CM. These high levels of sFRP-1 could be inhibiting WNT signaling and negatively impacting the growth of hESC grown in these CM. Indeed, a recent microarray study found increased expression of sFRP-1 (3.3-fold increase) and other inhibitors of WNT signaling in MEF feeder layers that were less supportive of hESC growth compared with those that were highly supportive of hESC growth [73]. Our data extend the inhibitory role of sFRP-1 on stem cell proliferation to human feeder layers. An even more dramatic change in sFRP-1 expression was seen in this study with the nonsupportive WI38 and Detroit 551 cell lines expressing 153- and 55-fold more sFRP-1, respectively, than the SDEC culture.

To further investigate the role sFRP-1 plays in affecting hESC growth, we increased the sFRP-1 concentration in SDEC CM growth media by supplementing the media with exogenous sFRP-1. These studies confirmed the inhibitory role of sFRP-1 on stem cell proliferation on both COL I and MAT. Our findings are consistent with a recent report indicating that the addition of sFRP family members to culture media caused a decrease in the percentage of undifferentiated hESC colonies grown on MEF feeder layers [73]. Interestingly, the negative effect of sFRP-1 on hESC proliferation seen in our study was more pronounced on COL I than it was on MAT. It is notable that heparin sulfate proteoglycan is one of the major components of MAT, along with laminin and type IV collagen [24,74]. sFRP-1 is known to bind strongly to heparin, which is widely utilized to purify sFRP-1 from culture media [48,49,75,76]. Indeed, the procedure used to purify the sFRP-1 from the conditioned culture media in this study employed a heparin affinity column. The presence of the heparin sulfate proteoglycan in MAT may serve to bind to sFRP-1 in the CM, effectively sequestering it and reducing its inhibitory activity. In contrast, COL I lacks heparin sulfate and its potential capacity to sequester sFRP-1. One of the reasons that MAT is such a highly effective hESC growth matrix may be its capacity to absorb compounds, such as sFRP-1, that negatively impact stem cell self-renewal.

Interestingly, our western blot data also indicate low levels of sFRP-1 in the MEF CM that was supportive of hESC proliferation on MAT. We recognize that the sFRP-1 antiserum used in the western blot analysis was generated against human sFRP-1 and that there might be a difference in its binding specificity with human versus mouse sFRP-1. However, the 14 amino acid synthetic peptide used to synthesize the antiserum differs by only 1 amino acid from the mouse sequence, and the entire sequences of the human and mouse proteins are 94% identical at the amino acid level. Therefore, the western blot is likely to be an appropriate indicator of the level of sFRP-1 in the MEF CM used in this study. Low levels of sFRP-1 in MEF CM would be expected since this medium is also highly supportive of hESC growth.

We estimate the sFRP-1 concentrations in the nonsupportive Detroit 551 and WI38 CM to be 25–50 ng/mL, whereas the sFRP-1 concentration required to negatively impact hESC growth in a 3-day assay was at least 200 ng/mL. The lower concentrations of sFRP-1 could affect hESC proliferation if the cells were exposed to it over a longer time period, such as the 3- to 4-week-long experiments done in this study. This idea is supported by the fact that we began seeing the negative effect of WI38 and Detroit 551 CM on hESC proliferation only after 2–3 weeks of exposure (Fig. 1). It is also likely that factors other than sFRP-1 in the CM affect hESC proliferation.

Western blot analysis also revealed an increase in the intracellular levels of PTGS2 in the SDEC culture compared with the nonsupportive feeder lines. PTGS2 is not a secreted protein and is therefore unlikely to be present in CM, but it is involved in the biosynthesis of prostaglandins, which are secreted. Following PTGS2 (or homologous prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 1) activity, the precursor prostaglandin H2 can be converted to different prostaglandins, including PGE2 and PGI2, which is generated by PGIS [77]. The microarray results also detected very high expression of PGIS in the SDEC culture compared with the nonsupportive feeder lines, suggesting that this prostaglandin synthesis pathway is elevated in SDEC. Our results support this notion, as SDEC CM contained 7- and 40-fold higher levels of PGE2 than Detroit 551 and WI38 CM, respectively. Likewise, SDEC CM contained 30- and 60-fold higher levels of 6-k-PGF1α (the stable hydrolysis product of PGI2) than Detroit 551 and WI38 CM, respectively. Taken together, our data indicate that increased expression of genes involved in prostaglandin synthesis, such as PTGS2 and PGIS, can indeed lead to increased secretion of certain prostaglandins into CM. Additionally, we found that PGE2 and 6-k-PGF1α levels were 3- and 10-fold higher in SDEC CM than in MEF CM, respectively.

The levels of PGE2 and PGI2 increase in the fallopian tubes (oviduct) following pregnancy, and these 2 prostaglandins, also produced in embryos, enhance embryo cell numbers, hatching, and implantation [77–83]. PGE2 was found to have a positive affect on the growth of hematopoietic stem cell progenitors obtained from zebrafish and mouse embryonic stem cells [84]. PTGS2 activity and PGE2 have also been associated with mouse embryonic stem cell proliferation [85–87] and prevention of apoptosis [88]. These data are in agreement with our findings of increased PTGS2 activity and PGE2 secretion in cells that are supportive of hESC growth. In this study, we also detected high expression of PGIS in cells that were supportive of hESC growth and found significantly higher concentrations of 6-k-PGF1α in hESC supportive CM than in nonsupportive CM. In a study on mouse embryonic stem cells, however, no PGIS was detected in the cell lysate and no 6-k-PGF1α was detected in the CM of undifferentiated cells [88]. Increased levels of PGI2 have also recently been associated with inducing hESC to form cardiomyocytes [89], indicating varying roles for PGI2 depending on the species and specific microenvironment. To our knowledge, our study is the first to indicate that both PTGS2 and PGIS may be associated with hESC self-renewal or survival.

Interestingly, downregulation of sFRP-1 and the increase in PTGS2 gene expression observed in the SDEC cells may not be unrelated. Recently, a link between the prostaglandin and WNT signaling pathways was reported in mouse hematopoietic stem cells [90]. Goessling et al. found that PGE2 regulates WNT signaling by direct phosphorylation of β-catenin and GSK-3 via cAMP/PKA signaling [90]. Increased levels of PTGS2 led to the stabilization of β-catenin and consequently to the enhanced formation and growth of hematopoietic stem cells [84,90]. In another study, increased expression of WNT (increased WNT signaling) led to increased levels of PTGS2 and increased PGE2 synthesis, suggesting that PTGS2 may be a transcriptional target for β-catenin or that transcription of PTGS2 is regulated by β-catenin-activated transcription factors [91]. Here, we found increased expression of genes involved in prostaglandin biosynthesis (PTGS2 and PGIS) and decreased expression of genes involved in inhibiting WNT signaling (sFRP-1) in the hESC-supportive SDEC cells. Thus, our work extends these previous studies by suggesting that the coordinated downregulation of WNT inhibitors (sFRP-1) and upregulation of factors that stimulate WNT signaling (PTGS2) had a positive impact on hESC proliferation.

In terms of optimizing medium conditions for hESC proliferation, the results presented here have begun to address the complexity of this issue. By eliminating direct contact with feeder cell lines and the use of the MAT, we are restricting the potential sources of variability to only those factors that are secreted by SDEC into the CM. The insights provided in this study by gene expression profiling of supportive and nonsupportive feeder layers suggest additional components that may facilitate hESC growth and may aid in the development of more defined medium conditions in the future. In addition, implementation of a collagen growth matrix may represent a significant advance for the expansion of hESC, as this matrix is defined, inexpensive, and readily scalable for clinical development.

Acknowledgments

Funding for the study described in this article was provided by Maryland Stem Cell Research Fund Award 2009MSCRF-E-0081.

Author Disclosure Statement

Under a licensing agreement between National Stem Cell, Inc., and the Johns Hopkins University, Dr. Shamblott is entitled to a share of royalty received by the University on sales of products/technologies described in this article. Dr. Shamblott was a paid consultant to National Stem Cell, Inc., at the time this work was carried out. The terms of this arrangement are being managed by the Johns Hopkins University in accordance with its conflict of interest policies.

References

- 1.Odorico JS. Kaufman DS. Thomson JA. Multilineage differentiation from human embryonic stem cell lines. Stem Cells. 2001;19:193–204. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.19-3-193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ho HY. Li M. Potential application of embryonic stem cells in Parkinson's disease: drug screening and cell therapy. Regen Med. 2006;1:175–182. doi: 10.2217/17460751.1.2.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Porat S. Dor Y. New sources of pancreatic beta cells. Curr Diab Rep. 2007;7:304–308. doi: 10.1007/s11892-007-0049-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shamblott MJ. Clark GO. Cell therapies for type 1 diabetes mellitus. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2004;4:269–277. doi: 10.1517/14712598.4.3.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scharfmann R. Alternative sources of beta cells for cell therapy of diabetes. Eur J Clin Invest. 2003;33:595–600. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2362.2003.01190.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nierras CR. Stallard J. Goldstein RA. Insel R. Human embryonic stem cell research and the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation International—a work in progress. Pediatr Diabetes 5 Suppl. 2004;2:94–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-543X.2004.00085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gallo P. Condorelli G. Human embryonic stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes: inducing strategies. Regen Med. 2006;1:183–194. doi: 10.2217/17460751.1.2.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sharma R. Raghubir R. Stem cell therapy: a hope for dying hearts. Stem Cells Dev. 2007;16:517–536. doi: 10.1089/scd.2006.0070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zweigerdt R. The art of cobbling a running pump—will human embryonic stem cells mend broken hearts? Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2007;18:794–804. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2007.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aberdam D. Gambaro K. Medawar A. Aberdam E. Rostagno P. de la Forest Divonne S. Rouleau M. Embryonic stem cells as a cellular model for neuroectodermal commitment and skin formation. C R Biol. 2007;330:479–484. doi: 10.1016/j.crvi.2007.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coutts M. Keirstead HS. Stem cells for the treatment of spinal cord injury. Exp Neurol. 2008;209:368–377. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2007.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Christou YA. Moore HD. Shaw PJ. Monk PN. Embryonic stem cells and prospects for their use in regenerative medicine approaches to motor neurone disease. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2007;33:485–498. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.2007.00883.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vugler A. Lawrence J. Walsh J. Carr A. Gias C. Semo M. Ahmado A. da Cruz L. Andrews P. Coffey P. Embryonic stem cells and retinal repair. Mech Dev. 2007;124:807–829. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2007.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Soto-Gutierrez A. Kobayashi N. Rivas-Carrillo JD. Navarro-Alvarez N. Zhao D. Okitsu T. Noguchi H. Basma H. Tabata Y. Chen Y. Tanaka K. Narushima M. Miki A. Ueda T. Jun HS. Yoon JW. Lebkowski J. Tanaka N. Fox IJ. Reversal of mouse hepatic failure using an implanted liver-assist device containing ES cell-derived hepatocytes. Nat Biotechnol. 2006;24:1412–1419. doi: 10.1038/nbt1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schwartz RE. Linehan JL. Painschab MS. Hu WS. Verfaillie CM. Kaufman DS. Defined conditions for development of functional hepatic cells from human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells Dev. 2005;14:643–655. doi: 10.1089/scd.2005.14.643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ameen C. Strehl R. Bjorquist P. Lindahl A. Hyllner J. Sartipy P. Human embryonic stem cells: current technologies and emerging industrial applications. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2008;65:54–80. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2007.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sartipy P. Bjorquist P. Strehl R. Hyllner J. The application of human embryonic stem cell technologies to drug discovery. Drug Discov Today. 2007;12:688–699. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2007.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martin MJ. Muotri A. Gage F. Varki A. Human embryonic stem cells express an immunogenic nonhuman sialic acid. Nat Med. 2005;11:228–232. doi: 10.1038/nm1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lei T. Jacob S. Ajil-Zaraa I. Dubuisson JB. Irion O. Jaconi M. Feki A. Xeno-free derivation and culture of human embryonic stem cells: current status, problems and challenges. Cell Res. 2007;17:682–688. doi: 10.1038/cr.2007.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mallon BS. Park KY. Chen KG. Hamilton RS. McKay RD. Toward xeno-free culture of human embryonic stem cells. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2006;38:1063–1075. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2005.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhan X. Hill C. Brayton CF. Shamblott MJ. Cells derived from human umbilical cord blood support the long-term growth of undifferentiated human embryonic stem cells. Cloning Stem Cells. 2008;10:513–522. doi: 10.1089/clo.2007.0087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chase LG. Firpo MT. Development of serum-free culture systems for human embryonic stem cells. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2007;11:367–372. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2007.06.421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oh SK. Choo AB. Human embryonic stem cells: technological challenges towards therapy. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2006;33:489–495. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2006.04397.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kleinman HK. McGarvey ML. Liotta LA. Robey PG. Tryggvason K. Martin GR. Isolation and characterization of type IV procollagen, laminin, and heparan sulfate proteoglycan from the EHS sarcoma. Biochemistry. 1982;21:6188–6193. doi: 10.1021/bi00267a025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ludwig TE. Levenstein ME. Jones JM. Berggren WT. Mitchen ER. Frane JL. Crandall LJ. Daigh CA. Conard KR. Piekarczyk MS. Llanas RA. Thomson JA. Derivation of human embryonic stem cells in defined conditions. Nat Biotechnol. 2006;24:185–187. doi: 10.1038/nbt1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Takahashi K. Tanabe K. Ohnuki M. Narita M. Ichisaka T. Tomoda K. Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell. 2007;131:861–872. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yu J. Vodyanik MA. Smuga-Otto K. Antosiewicz-Bourget J. Frane JL. Tian S. Nie J. Jonsdottir GA. Ruotti V. Stewart R. Slukvin II. Thomson JA. Induced pluripotent stem cell lines derived from human somatic cells. Science. 2007;318:1917–1920. doi: 10.1126/science.1151526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xu C. Inokuma MS. Denham J. Golds K. Kundu P. Gold JD. Carpenter MK. Feeder-free growth of undifferentiated human embryonic stem cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2001;19:971–974. doi: 10.1038/nbt1001-971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ludwig TE. Bergendahl V. Levenstein ME. Yu J. Probasco MD. Thomson JA. Feeder-independent culture of human embryonic stem cells. Nat Methods. 2006;3:637–646. doi: 10.1038/nmeth902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Peterson B. Zhang J. Iglesias R. Kabo M. Hedrick M. Benhaim P. Lieberman JR. Healing of critically sized femoral defects, using genetically modified mesenchymal stem cells from human adipose tissue. Tissue Eng. 2005;11:120–129. doi: 10.1089/ten.2005.11.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shen JT. Falanga V. Innovative therapies in wound healing. J Cutan Med Surg. 2003;7:217–224. doi: 10.1007/s10227-002-0106-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Klein AW. Collagen substances. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2001;9:205–218. viii. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Klein AW. Techniques for soft tissue augmentation: an “a to z.”. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2006;7:107–120. doi: 10.2165/00128071-200607020-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Izumi K. Song J. Feinberg SE. Development of a tissue-engineered human oral mucosa: from the bench to the bed side. Cells Tissues Organs. 2004;176:134–152. doi: 10.1159/000075034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dinh TL. Veves A. The efficacy of Apligraf in the treatment of diabetic foot ulcers. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;117:152S–157S. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000222534.79915.d3. discussion 158S–159S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baumann L. Kaufman J. Saghari S. Collagen fillers. Dermatol Ther. 2006;19:134–140. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8019.2006.00067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moore H. The medium is the message. Nat Biotechnol. 2006;24:160–161. doi: 10.1038/nbt0206-160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brafman DA. Shah KD. Fellner T. Chien S. Willert K. Defining long-term maintenance conditions of human embryonic stem cells with arrayed cellular microenvironment technology. Stem Cells Dev. 2009;18:1141–1154. doi: 10.1089/scd.2008.0410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xu RH. Peck RM. Li DS. Feng X. Ludwig T. Thomson JA. Basic FGF and suppression of BMP signaling sustain undifferentiated proliferation of human ES cells. Nat Methods. 2005;2:185–190. doi: 10.1038/nmeth744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Amit M. Shariki C. Margulets V. Itskovitz-Eldor J. Feeder layer- and serum-free culture of human embryonic stem cells. Biol Reprod. 2004;70:837–845. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.103.021147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brimble SN. Zeng X. Weiler DA. Luo Y. Liu Y. Lyons IG. Freed WJ. Robins AJ. Rao MS. Schulz TC. Karyotypic stability, genotyping, differentiation, feeder-free maintenance, and gene expression sampling in three human embryonic stem cell lines derived prior to August 9, 2001. Stem Cells Dev. 2004;13:585–597. doi: 10.1089/scd.2004.13.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Braam SR. Zeinstra L. Litjens S. Ward-van Oostwaard D. van den Brink S. van Laake L. Lebrin F. Kats P. Hochstenbach R. Passier R. Sonnenberg A. Mummery CL. Recombinant vitronectin is a functionally defined substrate that supports human embryonic stem cell self-renewal via alphavbeta5 integrin. Stem Cells. 2008;26:2257–2265. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2008-0291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shamblott MJ. Axelman J. Littlefield JW. Blumenthal PD. Huggins GR. Cui Y. Cheng L. Gearhart JD. Human embryonic germ cell derivatives express a broad range of developmentally distinct markers and proliferate extensively in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:113–118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.021537998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Richards M. Tan S. Fong CY. Biswas A. Chan WK. Bongso A. Comparative evaluation of various human feeders for prolonged undifferentiated growth of human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells. 2003;21:546–556. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.21-5-546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cowan CA. Klimanskaya I. McMahon J. Atienza J. Witmyer J. Zucker JP. Wang S. Morton CC. McMahon AP. Powers D. Melton DA. Derivation of embryonic stem-cell lines from human blastocysts. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1353–1356. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr040330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li C. Wong WH. Model-based analysis of oligonucleotide arrays: expression index computation and outlier detection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:31–36. doi: 10.1073/pnas.011404098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li C. Hung Wong W. Model-based analysis of oligonucleotide arrays: model validation, design issues and standard error application. Genome Biol. 2001;2:RESEARCH0032.1–RESEARCH0032.11. doi: 10.1186/gb-2001-2-8-research0032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Uren A. Reichsman F. Anest V. Taylor WG. Muraiso K. Bottaro DP. Cumberledge S. Rubin JS. Secreted frizzled-related protein-1 binds directly to Wingless and is a biphasic modulator of Wnt signaling. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:4374–4382. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.6.4374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Finch PW. He X. Kelley MJ. Uren A. Schaudies RP. Popescu NC. Rudikoff S. Aaronson SA. Varmus HE. Rubin JS. Purification and molecular cloning of a secreted, Frizzled-related antagonist of Wnt action. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:6770–6775. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.13.6770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Edgar R. Domrachev M. Lash AE. Gene Expression Omnibus: NCBI gene expression and hybridization array data repository. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:207–210. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.1.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Daheron L. Opitz SL. Zaehres H. Lensch MW. Andrews PW. Itskovitz-Eldor J. Daley GQ. LIF/STAT3 signaling fails to maintain self-renewal of human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells. 2004;22:770–778. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.22-5-770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Humphrey RK. Beattie GM. Lopez AD. Bucay N. King CC. Firpo MT. Rose-John S. Hayek A. Maintenance of pluripotency in human embryonic stem cells is STAT3 independent. Stem Cells. 2004;22:522–530. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.22-4-522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Li Y. Powell S. Brunette E. Lebkowski J. Mandalam R. Expansion of human embryonic stem cells in defined serum-free medium devoid of animal-derived products. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2005;91:688–698. doi: 10.1002/bit.20536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Xu C. Rosler E. Jiang J. Lebkowski JS. Gold JD. O'Sullivan C. Delavan-Boorsma K. Mok M. Bronstein A. Carpenter MK. Basic fibroblast growth factor supports undifferentiated human embryonic stem cell growth without conditioned medium. Stem Cells. 2005;23:315–323. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2004-0211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Xu C. Jiang J. Sottile V. McWhir J. Lebkowski J. Carpenter MK. Immortalized fibroblast-like cells derived from human embryonic stem cells support undifferentiated cell growth. Stem Cells. 2004;22:972–980. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.22-6-972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Stojkovic P. Lako M. Przyborski S. Stewart R. Armstrong L. Evans J. Zhang X. Stojkovic M. Human-serum matrix supports undifferentiated growth of human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells. 2005;23:895–902. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2004-0326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kerr DA. Llado J. Shamblott MJ. Maragakis NJ. Irani DN. Crawford TO. Krishnan C. Dike S. Gearhart JD. Rothstein JD. Human embryonic germ cell derivatives facilitate motor recovery of rats with diffuse motor neuron injury. J Neurosci. 2003;23:5131–5140. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-12-05131.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mueller D. Shamblott MJ. Fox HE. Gearhart JD. Martin LJ. Transplanted human embryonic germ cell-derived neural stem cells replace neurons and oligodendrocytes in the forebrain of neonatal mice with excitotoxic brain damage. J Neurosci Res. 2005;82:592–608. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Frimberger D. Morales N. Shamblott M. Gearhart JD. Gearhart JP. Lakshmanan Y. Human embryoid body-derived stem cells in bladder regeneration using rodent model. Urology. 2005;65:827–832. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2004.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shih YL. Hsieh CB. Lai HC. Yan MD. Hsieh TY. Chao YC. Lin YW. SFRP1 suppressed hepatoma cells growth through Wnt canonical signaling pathway. Int J Cancer. 2007;121:1028–1035. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rao M. Conserved and divergent paths that regulate self-renewal in mouse and human embryonic stem cells. Dev Biol. 2004;275:269–286. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Huang H. He X. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling: new (and old) players and new insights. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2008;20:119–125. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2008.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Miyabayashi T. Teo JL. Yamamoto M. McMillan M. Nguyen C. Kahn M. Wnt/beta-catenin/CBP signaling maintains long-term murine embryonic stem cell pluripotency. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:5668–5673. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701331104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pan G. Thomson JA. Nanog and transcriptional networks in embryonic stem cell pluripotency. Cell Res. 2007;17:42–49. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7310125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cai L. Ye Z. Zhou BY. Mali P. Zhou C. Cheng L. Promoting human embryonic stem cell renewal or differentiation by modulating Wnt signal and culture conditions. Cell Res. 2007;17:62–72. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7310138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Noggle SA. James D. Brivanlou AH. A molecular basis for human embryonic stem cell pluripotency. Stem Cell Rev. 2005;1:111–118. doi: 10.1385/SCR:1:2:111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sato N. Meijer L. Skaltsounis L. Greengard P. Brivanlou AH. Maintenance of pluripotency in human and mouse embryonic stem cells through activation of Wnt signaling by a pharmacological GSK-3-specific inhibitor. Nat Med. 2004;10:55–63. doi: 10.1038/nm979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Katoh M. WNT signaling pathway and stem cell signaling network. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:4042–4045. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Dreesen O. Brivanlou AH. Signaling pathways in cancer and embryonic stem cells. Stem Cell Rev. 2007;3:7–17. doi: 10.1007/s12015-007-0004-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Dravid G. Ye Z. Hammond H. Chen G. Pyle A. Donovan P. Yu X. Cheng L. Defining the role of Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in the survival, proliferation, and self-renewal of human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells. 2005;23:1489–1501. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bovolenta P. Esteve P. Ruiz JM. Cisneros E. Lopez-Rios J. Beyond Wnt inhibition: new functions of secreted Frizzled-related proteins in development and disease. J Cell Sci. 2008;121:737–746. doi: 10.1242/jcs.026096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kawano Y. Kypta R. Secreted antagonists of the Wnt signalling pathway. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:2627–2634. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Villa-Diaz LG. Pacut C. Slawny NA. Ding J. O'Shea KS. Smith GD. Analysis of the factors that limit the ability of feeder cells to maintain the undifferentiated state of human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells Dev. 2009;18:641–651. doi: 10.1089/scd.2008.0010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kleinman HK. McGarvey ML. Hassell JR. Star VL. Cannon FB. Laurie GW. Martin GR. Basement membrane complexes with biological activity. Biochemistry. 1986;25:312–318. doi: 10.1021/bi00350a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Chong JM. Uren A. Rubin JS. Speicher DW. Disulfide bond assignments of secreted Frizzled-related protein-1 provide insights about Frizzled homology and netrin modules. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:5134–5144. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108533200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zhong X. Desilva T. Lin L. Bodine P. Bhat RA. Presman E. Pocas J. Stahl M. Kriz R. Regulation of secreted Frizzled-related protein-1 by heparin. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:20523–20533. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609096200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wu KK. Liou JY. Cellular and molecular biology of prostacyclin synthase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;338:45–52. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Huang JC. Arbab F. Tumbusch KJ. Goldsby JS. Matijevic-Aleksic N. Wu KK. Human fallopian tubes express prostacyclin (PGI) synthase and cyclooxygenases and synthesize abundant PGI. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:4361–4368. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-020199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Huang JC. Wun WS. Goldsby JS. Wun IC. Noorhasan D. Wu KK. Stimulation of embryo hatching and implantation by prostacyclin and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor delta activation: implication in IVF. Hum Reprod. 2007;22:807–814. doi: 10.1093/humrep/del429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Huang JC. Goldsby JS. Arbab F. Melhem Z. Aleksic N. Wu KK. Oviduct prostacyclin functions as a paracrine factor to augment the development of embryos. Hum Reprod. 2004;19:2907–2912. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Huang JC. Wun WS. Goldsby JS. Matijevic-Aleksic N. Wu KK. Cyclooxygenase-2-derived endogenous prostacyclin enhances mouse embryo hatching. Hum Reprod. 2004;19:2900–2906. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Huang JC. Wun WS. Goldsby JS. Wun IC. Falconi SM. Wu KK. Prostacyclin enhances embryo hatching but not sperm motility. Hum Reprod. 2003;18:2582–2589. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deg490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Huang JC. Wun WS. Goldsby JS. Egan K. FitzGerald GA. Wu KK. Prostacyclin receptor signaling and early embryo development in the mouse. Hum Reprod. 2007;22:2851–2856. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dem304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.North TE. Goessling W. Walkley CR. Lengerke C. Kopani KR. Lord AM. Weber GJ. Bowman TV. Jang IH. Grosser T. Fitzgerald GA. Daley GQ. Orkin SH. Zon LI. Prostaglandin E2 regulates vertebrate haematopoietic stem cell homeostasis. Nature. 2007;447:1007–1011. doi: 10.1038/nature05883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kim YH. Han HJ. High-glucose-induced prostaglandin E(2) and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor delta promote mouse embryonic stem cell proliferation. Stem Cells. 2008;26:745–755. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Lee SH. Na SI. Heo JS. Kim MH. Kim YH. Lee MY. Kim SH. Lee YJ. Han HJ. Arachidonic acid release by H2O2 mediated proliferation of mouse embryonic stem cells: involvement of Ca2+/PKC and MAPKs-induced EGFR transactivation. J Cell Biochem. 2009;106:787–797. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Yun SP. Lee MY. Ryu JM. Han HJ. Interaction between PGE2 and EGF receptor through MAPKs in mouse embryonic stem cell proliferation. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2009;66:1603–1616. doi: 10.1007/s00018-009-9076-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Liou JY. Ellent DP. Lee S. Goldsby J. Ko BS. Matijevic N. Huang JC. Wu KK. Cyclooxygenase-2-derived prostaglandin e2 protects mouse embryonic stem cells from apoptosis. Stem Cells. 2007;25:1096–1103. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Xu XQ. Graichen R. Soo SY. Balakrishnan T. Rahmat SN. Sieh S. Tham SC. Freund C. Moore J. Mummery C. Colman A. Zweigerdt R. Davidson BP. Chemically defined medium supporting cardiomyocyte differentiation of human embryonic stem cells. Differentiation. 2008;76:958–970. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.2008.00284.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Goessling W. North TE. Loewer S. Lord AM. Lee S. Stoick-Cooper CL. Weidinger G. Puder M. Daley GQ. Moon RT. Zon LI. Genetic interaction of PGE2 and Wnt signaling regulates developmental specification of stem cells and regeneration. Cell. 2009;136:1136–1147. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Howe LR. Subbaramaiah K. Chung WJ. Dannenberg AJ. Brown AM. Transcriptional activation of cyclooxygenase-2 in Wnt-1-transformed mouse mammary epithelial cells. Cancer Res. 1999;59:1572–1577. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]