Abstract

Aims

The study of the intracellular oxido-reductive (redox) state is of extreme relevance to the dopamine (DA) neurons of the substantia nigra pars compacta. These cells possess a distinct physiology intrinsically associated with elevated reactive oxygen species production, and they selectively degenerate in Parkinson's disease under oxidative stress conditions. To test the hypothesis that these cells display a unique redox response to mild, physiologically relevant oxidative insults when compared with other neuronal populations, we sought to develop a novel method for quantitatively assessing mild variations in intracellular redox state.

Results

We have developed a new imaging strategy to study redox variations in single cells, which is sensitive enough to detect changes within the physiological range. We studied DA neurons' physiological redox response in biological systems of increasing complexity—from primary cultures to zebrafish larvae, to mammalian brains—and identified a redox response that is distinctive for substantia nigra pars compacta DA neurons. We studied simultaneously, and in the same cells, redox state and signaling activation and found that these phenomena are synchronized.

Innovation

The redox histochemistry method we have developed allows for sensitive quantification of intracellular redox state in situ. As this method is compatible with traditional immunohistochemical techniques, it can be applied to diverse settings to investigate, in theory, any cell type of interest.

Conclusion

Although the technique we have developed is of general interest, these findings provide insights into the biology of DA neurons in health and disease and may have implications for therapeutic intervention. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 15, 855–871.

Innovation

Currently available techniques to study cellular redox state often employ genetic manipulation; assess the GSH/GSSG redox couple, thereby neglecting the contribution of protein thiols; and are incompatible with simultaneous studies of redox-associated phenomena (e.g., signaling). The redox histochemistry method we describe herein overcomes these limitations and can be used on tissue biopsies and thus has substantial clinical relevance.

Introduction

Cellular metabolism is associated with oxido-reductive (redox) reactions, in which electrons flow among various chemical species—according to a gradient in their redox potential (Eh)—to reach the final acceptor, oxygen. Under physiological conditions, the cell maintains redox homeostasis by controlling the ratio of oxidized to reduced chemical species. While fluctuations in this balance occur under normal conditions, an excessive shift toward more oxidized states—oxidative stress—can be lethal for the cell (28, 29). The redox homeostasis of the cell is tightly controlled and the responsible regulatory mechanisms principally rely on thiol groups of cysteine (cys) residues. Because of their unique chemical properties, this functional group is extremely reactive toward reactive oxygen species (ROS), rendering cys primary ROS sensors (62). Thiol groups buffer the oxidation in the cellular environment by undergoing an oxidative condensation of two thiols to form a disulfide. Therefore, in a given redox state, cys-containing species coexist in a dynamic equilibrium between the reduced and oxidized forms, in a ratio that reflects the intracellular redox state (59). Extensive attention has been dedicated to the role of the small tri-peptide glutathione (GSH) in redox homeostasis. However, it is now very clear that protein thiols (pr-SH)—which are present in specialized proteins such as thioredoxins and in other proteins that possess primary functions other than controlling the redox state—also significantly contribute to redox homeostasis (1, 35, 59). In several cases, the reversible oxidation of pr-SH also performs a fundamental regulatory function and acts as a molecular switch, whereby protein activity is modulated through oxidation or reduction of thiols in critical positions. In this respect, thiol oxidation constitutes the major mechanism of integration between ROS and signaling (17, 21, 62). In summary, understanding how ROS modulate the intracellular thiol redox state in health and disease is critical to unraveling the responses activated by the cell to preserve normal function and prevent pathogenesis under conditions of redox imbalance.

Dopamine (DA) neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNpc) are part of the basal ganglia circuitry and selectively degenerate in Parkinson's disease (PD) (10, 58). The study of redox homeostasis in SNpc DA neurons is of extreme interest to understand the biology of these cells, as their particular physiology is intrinsically associated with elevated ROS production. DA neurons are spontaneous pacemaking cells, and generate rhythmic action potentials in the absence of synaptic inputs. While most neuronal types use Na+ to generate their action potentials, SNpc DA neurons rely on Ca2+, which enters the cytoplasm through L-type channels (12, 52, 55). Over time, the spontaneous activity of these neurons could lead to elevated and harmful concentrations of cytosolic Ca2+. This potential harm can be prevented by the buffering activity of certain organelles, such as mitochondria. However, this activity is invariably associated with ROS production (14, 15). In addition, excess ROS could derive directly from DA metabolism, which generates harmful by-products such as semiquinones and hydrogen peroxide (33). The overall result is an increase in the basal levels of ROS in SNpc DA neurons that impairs their ability to tolerate further oxidative insults. In fact, systemic administration of pro-oxidants—which in principle target every cell in the brain—results in the selective damage of the DA system, and chronic administration of ROS producers, such as rotenone and paraquat, successfully mimic PD pathogenesis (9, 47). Taken together, the above evidence supports the concept that SNpc DA neurons must manage ROS in a particular manner. We hypothesize that the effects of mild, physiological amounts of ROS on the cellular redox state will be different in SNpc DA neurons as compared with other types of neurons that do not share the same physiology.

This hypothesis is testable if the redox state can be determined in specific single neurons of interest, with a method sensitive enough to detect mild variations in the intracellular redox state, within the physiological range. For this purpose, we developed a novel histochemical strategy for fluorescence imaging, in which oxidized and reduced thiol residues are labeled differentially. The technique provides a sensitive and ratiometric read-out of the redox state, which is expressed as the ratio between the signals of oxidized and reduced thiols. We applied this method to study the physiological redox response in DA neurons, which was elicited by nonlethal doses of the pro-oxidant rotenone. Our results indicate that the response in DA neurons is distinctive, and presents features that were not observed in cortical neurons. Moreover, sublethal doses of rotenone induce a reaction in SNpc DA neurons, but not in those in the ventral tegmental area (VTA) or cortical ones. Finally, we studied simultaneously, in the same cells, the intracellular redox state and the activation of the mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway. We found that signaling activation is multiphasic and synchronized with the redox variations, with oxidation anticipating MAPK phosphorylation. Importantly, these features are hallmarks of DA neurons, as they were not observed in cortical neurons.

In summary, we have developed a new imaging approach to study redox homeostasis, and provided direct evidence in primary culture, zebrafish larvae, and rat that pro-oxidants elicit a distinctive response in DA neurons. While our new methodology is of general interest, and is broadly applicable to any study involving redox biology, our findings provide new important elements to understand the biology of DA neurons in health and disease, and to test future treatments for PD.

Materials and Methods

Materials

All reagents were from Sigma, unless otherwise specified. All animal use followed the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee–approved protocols. Lewis rats were treated with rotenone as previously described (9). TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) was purchased from ProSpec (Protein-Specialists).

Cell cultures

Primary cocultures

Astrocyte-neuron cocultures were prepared as previously described (23, 56), with minor modifications. Cells were plated in poly-D-lysine coated plates. Astrocyte cultures were prepared at least 1 week in advance of neuronal cultures. Newborn P1 rat pups were anesthetized by hypothermia. Brains were extracted and immersed in cold Leibovitz's L-15 Medium (Sigma), 200 I.U./ml Pennicillin, 200 μg/ml Streptoycin (Cellgro), where the dissections were performed. Following anatomical landmarks, the SN, without the VTA, was dissected from a coronal midbrain slice. For the preparation of cortical neurons and astrocytes, the frontal cortex was used. The tissue was cut into small pieces and enzymatically dissociated in 2.5 g/l of Trypsin, 0.38 g/l of ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) (0.25% Trypsin-EDTA, Cellgro), 0.5 mM of kynureic acid in Hanks' Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS) without Ca2+ and Mg2+ for 30 min at 37°C. For astrocytes preparation, kynureic acid was omitted from the enzymatic solution. Cells were triturated with a fire-polished Pasteur pipette and washed three times with Neurobasal medium (neuronal cultures; Invitrogen), or with Leibowitz's L-15 medium containing 15% horse serum (astrocytes). Cells were plated at a density of 5×104 cells/cm2 in neurobasal medium (neurons), or Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium containing 15% horse serum (astrocytes). Astrocyte cultures were washed after 4 h from plating with cold medium to remove neurons. Neurons were plated on top of a glial layer. Three hours before neurons were plated, glial culture L-15 medium was replaced with neurobasal medium. After 1 day, glial cell-derived neurotrophic factor 10 ng/ml was added to the neuronal cultures. The next day the growth of non-neural cells was inhibited with 5-fluorodeoxyuridine 6.7 μg/ml and uridine 16.5 μg/ml. Cultures were used after 14 days in vitro.

Secondary cell cultures

SH-SY5Y, HEK 293T, and NIH-3T3 cell lines were cultured according to standard procedure in 37°C, 5%CO2 atmosphere. Endoplasmic reticulum in NIH-3T3 cells was labeled using ER-targeted red fluorescent protein (CellLight™; Invitrogen) according to the directions of the manufacturer.

Detection of ROS

ROS were detected using the probe MitoSOX (Invitrogen), as described by Johnson-Cadwell and co-workers (34). For live imaging analysis of primary neurons, neurobasal medium was replaced with HBSS. MitoSOX was used at a final concentration of 0.2 μM, and was added at the beginning of the imaging session. For fluorescence recording, a Leica microscope was used. Fluorescence was recorded using excitation light (510 nm) provided by a 75 W xenon lamp-based monochromator (T.I.L.L. Photonics GmbH); emission (580 nm) was detected using a CCD camera (Orca; Hamamatsu). Alternatively, ROS were measured with the probe chloromethyl (CM)-H2-2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCFDA) (Invitrogen). Here primary neurons were incubated 30 min in 10 μM CM-H2-DCFDA in HBSS, 37°C, 5%CO2. The cultures were washed once in warm HBSS (37°C), and incubated with the pro-oxidants prepared in HBSS for 30 min. CM-H2-DCFDA becomes fluorescent after exposure to ROS, and its emission at 523 nm after excitation at 495 nm was measured with a SpectraMax Gemini EM multiplate reader (Molecular Devices).

Redox immunohistochemistry

The redox immunohistochemistry (RHC) was developed from a previous protocol we had developed and published (46). Alexa680 maleimide and Alexa 555 maleimide were purchased from Invitrogen. IR-Dye 800 maleimide was purchased from LiCor.

Cell cultures

Cells were fixed for 30 min in 4% paraformaldehyde, 1 mM N-ethylmaleimide, 2 μM Alexa680 maleimide, and 0.05% Triton X-100 prepared in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (pH 7.0). It is critical to control the pH of PBS to avoid nonspecific reactions (45). Cells were washed three times for 5 min in PBS to remove excess unreacted dye and then incubated for 30 min in 5 mM tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP) in PBS. Because TCEP reacts minimally with maleimide, it was possible to wash cells very quickly (<30 s) in PBS; this step prevented air-induced re-oxidation of previously reduced thiols. The second labeling step was performed by incubating cells for 30 min in 1 mM N-ethylmaleimide and 2 μM Alexa555 maleimide prepared in PBS. After three additional washing steps in PBS (three times for 5 min), the staining was completed and cells were ready for further immunochemical staining.

Zebrafish larvae

Stocks of adult Tg(eno2:egfp) (7) and Tg(slc6a3:egfp) (6) zebrafish were maintained at 28.58°C. Embryos were raised in E3 buffer (5 mM NaCl, 0.17 mM KCl, 0.33 mM CaCl2, and 0.33 mM MgSO4) at 28.5°C. Transgenic heterozygote embryos, obtained by crossing homozygote Tg(Eno2:GFP) or Tg(slc6a3:egfp) with wild-type AB* strain, were used for experiments. The RHC in zebrafish is very similar to that in cell cultures, with minor modification. In particular, while the concentration of the reagents is identical, the protocol involves longer incubation times. Larvae were fixed overnight at 4°C in 4% paraformaldehyde, 1 mM N-ethylmaleimide, 2 μM Alexa680 maleimide, and 0.05% Triton X-100 prepared in PBS pH 7.0. Excess of alkylating agents was removed with several washes of 30 min each in PBS. The reducing step was performed for 6 h in 5 mM TCEP in PBS. Excess TCEP was removed with five washes of 15 min each in PBS. The second labeling step was performed by incubating the larvae overnight at 4°C in 1 mM N-ethylmaleimide and 2 μM Alexa555 maleimide prepared in PBS. After a final set of washes to remove excess of alkylating agents, three times for 20 min each, the larvae were embedded in 1.5% low-melting-point agarose in E3 buffer and analyzed by laser scanning confocal microscopy.

Brain tissues

Rats were deeply anesthetized and euthanized by decapitation. Brains were removed and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen. For RHC, brains from control and rotenone-treated animals (n=2) were processed the same day, with the same solutions. Brains were cut on a cryostat (20 μm sections) and once on the slide the sections were immediately fixed and the redox state blocked in 4% paraformaldehyde, 1 mM N-ethylmaleimide, and 2 μM Alexa680 maleimide for 30 min. In a set of control sections, which were used to test the effects of air oxidation (Supplementary Fig. S1a; Supplementary Data are available online at www.liebertonline.com/ars), this step was delayed, and fixed, but unblocked sections (i.e., 4% paraformaldehyde, but not maleimide and Alexa680 maleimide) were exposed to atmospheric oxygen for 2 h. After this time, sections were treated as above with the Alexa680-maleimide solution and TCEP. In the second labeling step, IR-Dye 800-maleimide was used instead of Alexa555 maleimide (LiCor) because the sections were imaged with an Odyssey infrared scanner (LiCor), which allows the simultaneous analysis of a large number of sections. After the first labeling step, excess alkylating reagents were removed with three washes of 5 min, and sections were reduced with 5 mM TCEP in PBS, for 30 min. After a quick wash in PBS, the second labeling step and the following washes were performed as in the cell cultures. At this point, sections were ready for further immunochemical staining.

RHC in cells incubated in redox buffers

Cells were fixed in redox buffers as previously described, with minor modifications (46). Briefly, different amounts of oxidized and reduced GSH were combined in 4% paraformaldehyde (0.5 M Tris-HCl, pH 7.4) and 0.02% Triton X-100 to obtain solutions at the desired redox potential (−180 mV: GSH 3.5 mM, oxidized glutathione [GSSG] 1.5 mM; −210 mV: GSH 4.75 mM, GSSG 0.25 mM; −240 mM: GSH 4.98 mM, GSSG 0.02 mM; −270 mM: GSH 4.998 mM, GSSG 2 μM; −300 mM: GSH 4.9998 mM, GSSG 0.2 μM). Cells were fixed in the redox buffered paraformaldehyde for 1 h, and then the RHC was performed.

Measure of the redox state of GSH and protein thiols

Levels of oxidized and reduced GSH were measured with the GSH, GSSG, and total assay kit from Biovision.

To measure the ratio between oxidized and reduced protein thiols, cells were lysed in 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.0, 2% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), 1 mM EDTA, and 5μM Alexa680-maleimide, containing a protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma). The lysate was heated at 65°C for 5 min to denature proteins and incubated 20 min at room temperature. Proteins were precipitated in ice-cold acetone to remove un-reacted reagents; resuspended in 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7, 2% SDS, and 10 mM TCEP; heated at 65°C for 5 min; and incubated 20 min at room temperature to label free thiols. Proteins were precipitated again and the pellet was resuspended in 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7, 2% SDS, and 5 μM IRDye-800 maleimide (LiCor) to label the formerly oxidized thiols. After 20 min of incubation, the proteins were precipitated and spotted on a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (0.2 μm Immobilon PSQ; Millipore); the membrane was scanned, acquired, and imaged with an Odyssey infrared scanner (LiCor), and the signal was quantified with the scanner's software.

Immunohistochemistry

After RHC, specimens were washed in PBS and processed for immunohistochemistry (IHC) according to standard procedures (45). Samples were fixed and then blocked in 10% donkey serum. Primary antibodies were used at the following concentrations: tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) (AB1542; Millipore) 1:2000; DA transporter (DAT) (AB369; Millipore) 1:2000; microtubule associated protein 2 (AB5622; Millipore) 1:2000; extracellular signal-regulated kinases (Erk) 1/2 (4695; Cell Signaling) 1:500; phospho-Erk1/2 (9106; Cell Signaling) 1:500; PDI (ab2792; Abcam) 1:800; GSH (Ab5010; Millipore) 1:500; and mitochondrial Hsp60 (Spa807; Stressgen) 1:500.

The specificity of the anti-GSH antibody was tested by performing negative control experiments in which cellular GSH was depleted by the following means: (i) overnight incubation in 50 μM buthionine sulphoximine; (ii) 10-min incubation with 5 μM digitonin or with 5 μM digitonin with 1 mM DL-dithiothreitol. An additional control was performed by preabsorbing the antibody with GSH (Supplementary Fig. S1l).

Image acquisition and analysis

Specimens were acquired with an Olympus Fluoview 1000 laser scanning confocal microscope. The pinhole was adjusted to obtain a 1-μm-thick optical slice. The detection parameters were set in the control reaction and were kept constant across specimens. The ratio between the SS and the SH signal was calculated by the confocal software, which also generated the ratio images. The ratio was set equal to 1 in the control specimen, which was the control reaction of cortical neurons for all the experiments. For the analysis within DA neurons, only DAT+ neurons were considered in cell cultures (Supplementary Fig. S2), and only TH+ neurons in tissue sections. In zebrafish, only neurons in the anterior aspect of the midbrain GFP+ cluster were used for the analysis, as they have been shown to be dopaminergic (6). Images were analyzed in a semi-automated fashion with Metamorph software (Molecular Devices). The signal of the cellular markers (i.e., DAT, microtubule associated protein 2, and TH) was used by the software to automatically generate regions of interest (ROI) around the cells of interest. The software measures the signal intensity within the ROIs and each ROI represents a dot in the scatter plots. 4Pi microscopy (50) was performed with a Leica TCS 4Pi unit equipped with argon and a Mai Tai tunable multiphoton laser. Cells enclosed in two quartz coverslips were observed with two HCX PL APO 100×glycerol N.A. 1.35 0.22/0.22 objectives. Optical thickness was set to 0.09 μm. Three-dimensional reconstruction was performed with Amira® 5 software (Visage Imaging GmbH), applying a threshold of 50 (over a maximum of 255) to the signal to eliminate reduced regions.

Statistics

Experiments were performed in four to six independent biological replicates. Statistical analysis was performed with Prism4 (GraphPad Software). The values of the redox state at different time points did not exhibit a Gaussian distribution, for either DAT+ or cortical neurons, as calculated with the D'Agostino and Pearson omnibus normality test normality test (p<0.0001). Under these conditions the analysis of variance test cannot be applied, and therefore the statistical significance between time points was calculated with a Kruskal-Wallis test, followed by a Dunn's multiple comparison test. The significance of variances was calculated using the f-test. Frequency distribution was calculated using a 0.2 bin width.

Results

Description and validation of the technique

The redox imaging technique—or RHC—takes advantage of the ability of thiol groups in GSH and proteins to sense the cellular redox environment, which therefore can be studied by monitoring the ratio of oxidized to reduced thiols (Fig. 1a). This task can be accomplished by performing step-wise differential labeling, in which reduced (SH) and oxidized thiol (SS) groups are sequentially tagged with two different fluorophores (Fig. 1b). The technique is described in detail in the Materials and Methods section.

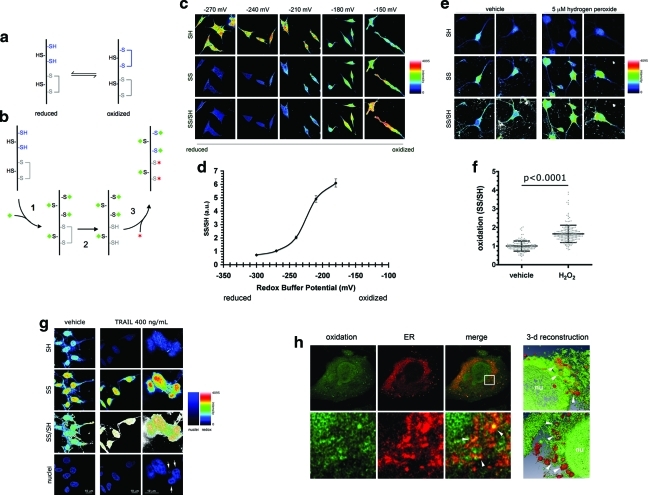

FIG. 1.

Validation of the redox histochemistry method. (a) Schematic of the equilibrium between reduced (left) and oxidized (right) thiol-containing chemical species in the cellular environment. The equilibrium will shift toward one or the other of the species depending upon the physiological or pathophysiological state of the cell (27). Only certain thiols are redox sensitive (depicted in blue); other thiols are always present in a reduced (black) or in an oxidized (gray) form, and are not involved in redox regulation. (b) Schematic describing the strategy used to perform the differential labeling of oxidized and reduced thiols for redox immunohistochemistry (RHC). In the initial step, thiols in the reduced form are labeled with the first maleimide-conjugated dye (shown in green). In the second step, thiols are released from oxidized disulfides using the reducing agent tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP), whose chemistry interferes minimally with the maleimide-thiol reaction. In the final step, the newly formed reduced thiols are labeled with a second maleimide-conjugated dye (shown in red). (c) Differential labeling of total thiols senses artificially induced changes in the redox state. SH-SY5Y cells were fixed in solutions of known redox potential (Eh), obtained by mixing the redox couple glutathione (GSH)/oxidized glutathione (GSSG) in different proportions. As the conditions are set at less negative, that is, more oxidizing Eh values, a decrease in the signal of reduced thiols (SH) is paralleled by an increase in the signal of the oxidized thiols (SS). As expected, the ratio signal SS/SH increases with oxidation. (d) Quantitative analysis of the imaging data indicates that the approach can detect variations in a wide range Eh values, including physiological Eh values. (e) Exposure of primary mesencephalic neurons to 5 μM hydrogen peroxide induces detectable variations in the total thiols redox state (t-test, p<0.0001). (f) Quantitative analysis of the imaging data indicates that hydrogen peroxide exposure causes a significant increase in oxidation. In the scatter plot graph, each point corresponds to a different region of interest localized in the cytosol of a neuron. (g) Detection of intracellular oxidation as a consequence of apoptosis induced by the TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL). Exposure to TRAIL for 16 h induces apoptotic fragmentation of nuclei (arrows) and is accompanied by a remarkable increase in the intracellular redox state. (h) RHC detects areas of higher oxidation at the subcellular level. 4Pi microscopy was performed on cells expressing ER-targeted RFP (red) and prepared for RHC to label only the oxidized disulfides (green). Yellow colocalization indicates ER areas with higher oxidation. Lower panel depicts a zoom of the area enclosed in the white square in which oxidation signal appears as a heterogeneous network overlapping with ER (arrowheads). The right portion of the panel depicts two different three-dimensional reconstructions of oxidation (green) in ER-labeled (red) cells. Arrowheads point to areas in which oxidation and ER overlap. In these images empty portions represent reduced areas. nu, nucleus. (To see this illustration in color the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertonline.com/ars).

Initially, we sought to determine the accuracy and sensitivity of the method. For this purpose, we performed RHC in SH-SY5Y cells that had been fixed in solutions of known redox potential (Eh), buffered by varying ratios of GSH/GSSG. The final concentration Cfin=[GSH]+[GSSG] was kept constant and equal to 5 mM, which is comparable with observed physiological values (59). As expected, at more oxidizing (i.e., less negative) Eh values, we observed an increase in the SS signal, which was paralleled by a decrease in the intensity of the SH signal. When the ratio between signals (SS/SH)—which is proportional to the oxidation levels—was calculated, an increase was observed at less negative Eh values (Fig. 1c). When calculated on the basis of the GSH/GSSG redox couple, the intracellular Eh has been estimated to be −260 mV in undifferentiated cells and −200 mV in differentiated cells; in cells under oxidative stress conditions, Eh has been estimated to be around −160 mV (36). Over this range of values, our method can clearly sense variations in the cellular redox state (Fig. 1d), and we therefore concluded that the approach is adequate to investigate the cellular redox state in physiological and pathological situations. On these premises, we sought to determine if the redox staining was able to detect an increase in oxidation in cells treated with low doses of pro-oxidants. When ventral mesencephalic (VM) primary neurons were treated with 5 μM H2O2, a significant increase in oxidation was detected after 30 min of treatment (Fig. 1e, f). Importantly, in physiological conditions the intracellular concentration of H2O2 has been estimated to be in the low micromolar range (4); therefore, the working concentration we used in this set of experiments is of physiological relevance. Under these conditions, we did not detect any apoptosis, necrosis, or neurite fragmentation (data not shown).

H2O2 can directly oxidize thiols (63), and therefore the signal detected in the latter experiment could be due to depletion of SH because of their interaction with the oxidant. To validate the method also in those conditions where redox changes are caused indirectly, we explored the ability of our system to detect oxidation occurring during apoptosis. This is a well-described phenomenon caused by increased ROS production and, to some extent, by active extrusion of GSH (20, 22). For this purpose, we used the tumor necrosis factor member TRAIL, which has been used for the same purpose in other studies (26). As expected, treatment with TRAIL induced apoptosis in HEK293 cells, as revealed by fragmentation of nuclei; cell death was associated with a remarkable increase in oxidation within dying cells (Fig. 1g). The method was also able to detect air-induced thiol oxidation in tissues (Supplementary Fig. S1a). As a general control, if thiols were preblocked with the nonfluorescent alkylating agent maleimide or if the reducing step were omitted, no signal was detected (Supplementary Fig. S1b). The method measures the state of the total thiol pool in the cell and is not bound to any particular redox couple (i.e., GSH or protein thiols [pr-SH]), as suggested by the parallel assay of GSH/GSSG, pr-SH/pr-SS, and RHC (Supplementary Fig. S1c, d). When tested in PC12 cells, the RHC followed the redox trend of the GSH/GSSG couple, whereas the pr-SH redox state did not change (Supplementary Fig. S1c). On the contrary, in primary VM cultures and DA neurons—in which GSH depletion appears to be less harmful than in other cultures (25, 51, 61)—the redox state of the GSH/GSSG couple was rather stable, the pr-SH redox state changed during the treatment, and the pattern of the measures provided by RHC was different from the trend of both GSH and pr-SH (Supplementary Fig. S1d). In summary, the measure provided by RHC determines the general redox state, which will largely depend on the dominant redox buffering couples in the experimental system under analysis. Taken together, these findings demonstrate that the method is suitable to image intracellular variations in the redox state under physiological levels of oxidation. Moreover, when used in combination with higher resolution imaging techniques such as 4Pi microscopy (50), the method can detect differences in oxidation at the subcellular level. As expected, the endoplasmic reticulum appears as an area of higher oxidation (Fig. 1h). It is intriguing that higher magnification images generated with 4Pi microscopy reveal that the signal of oxidation is a heterogeneous network; this evidence, which was undetectable by conventional confocal microscopy (Supplementary Fig. S1m), is consistent with the notion that intracellular redox state differs substantially between subcellular compartments (Fig. 1h).

Rotenone induces different responses in dopaminergic and cortical neurons in primary cultures

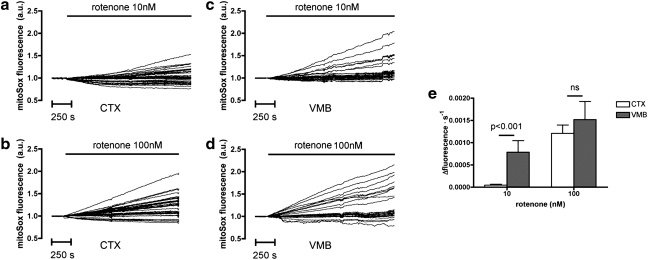

The pesticide rotenone—an inhibitor of the mitochondrial respiratory chain complex I—induces selective toxicity in DA neurons of the SNpc in various animal models of PD (2, 9). While inhibition of mitochondrial respiration might lead to bioenergetic defects caused by depletion of ATP, the mechanisms responsible for the selective toxicity of rotenone have been shown to lie rather in the increased production of ROS associated with blocking of complex I (60). On these premises, we reasoned that rotenone administration would constitute an ideal experimental approach to describe the specific characteristics of the response of DA-neurons to oxidative insults. Therefore, we compared—during a 24-h (1440 min) time-course study—the variations in the redox state induced by 10 nM rotenone, in DAT-positive (DAT+) neurons from VM neuronal primary cultures (Supplementary Fig. S2), and in cortical neurons. Initially, we sought to determine the amount of ROS generated in our experimental system. When we used the probe mitoSOX to measure the production of superoxide (O2−) in mitochondria, which are the specific site of rotenone-mediated ROS generation, we found that the rate of O2− generation induced by low rotenone concentrations (10 nM) was significantly higher in VM than in cortical (CTX) cultures (Fig. 2a–e). Conversely, using the probe CM-H2-DCFDA, which is neither specific for any particular ROS nor for any subcellular compartment, we were not able to detect any significant difference between VM and CTX cultures (Supplementary Fig. S3c). However, our RHC method reliably detected rotenone-induced variations in intracellular redox state (Fig. 3a), and the time-course analysis revealed several interesting differences between DAT+ and cortical neurons. In these conditions we did not observe any signs of neurite fragmentation or cell death, in the form of necrosis or apoptosis, as evidenced by SytoxGreen cell death assay—a test for necrosis-induced permeabilization of plasma membranes (60)—and by the absence of caspase-3 cleavage (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Real-time measurement of rotenone-induced superoxide production in neurons using the MitoSox probe. (a–d) Representative traces of individual neurons showing changes in MitoSox fluorescence following rotenone administration. The signal is normalized with baseline fluorescence detected before rotenone application. In the studied time frame (30 min) the increment in fluorescence is linear, and, as expected, administration of higher concentrations of rotenone (100 nM) induces a more robust increment in the MitoSox signal. (e) Bar graph showing the average rate of increment in MitoSox fluorescence. Treatment with 10 nM rotenone induces a significantly higher rate of reactive oxygen species production in ventral mesencephalic (VM) cultures (left bars). The trend is also observed when cells are treated with 100 nM rotenone, even though statistical significance is not reached. ns, not significant.

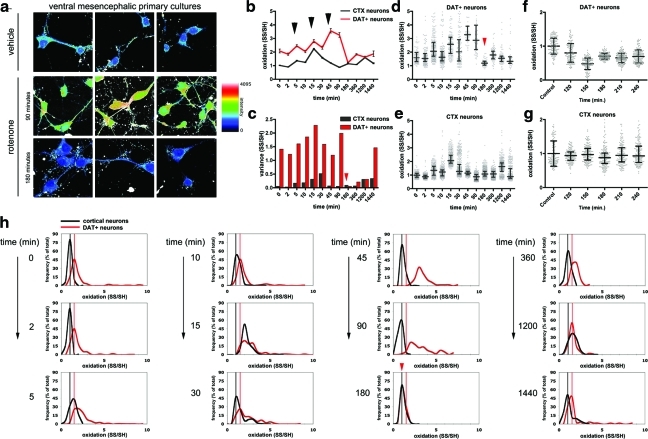

FIG. 3.

Rotenone induces different redox response in primary midbrain dopaminergic neurons versus primary cortical neurons. (a) Representative images of primary rat mesencephalic cultures stained for oxidized and reduced thiols. The montage depicts the ratio SS/SH in neurons treated with vehicle or with 10 nM rotenone for 90 and 180 min, which represent a peak of oxidation and the clamped reduced state, respectively. In the scale, more oxidized states are shown in red, whereas less oxidized states are shown in blue. While a significant increase in oxidation is detected after 90 min, at the 180 min time-point the cellular redox state is in a relatively reduced state. (b) Comparison of the variations in redox state between dopamine transporter-positive (DAT+) neurons and cortical neurons in response to 10 nM rotenone treatment. Black arrowheads indicate the peaks of oxidation. Data represent the mean with standard error of the mean. Differences (except for the 180 and 1200 min time-points) are statistically significant when analyzed with Kruskal-Wallis test (p<0.0001), followed by Dunn's post-test (p<0.001). (c) Graph of the variances observed during rotenone treatment in DAT+ and cortical neurons. The clamped, reduced state observed in DAT+ neurons is indicated by the red arrowhead. (d, e) The scatter plots, in which each dot represents a different neuron, reveal that DAT+ neurons have a wider redox state spread over much of the course of rotenone treatment. Medians with the interquartile range are superimposed on the scatter plots. The clamped, reduced state observed in DAT+ neurons is indicated by the red arrowhead. Variances are significantly different (p<0.001, Kruskal-Wallis test, followed by a Dunn's multiple comparison test). (f, g) Time points around 180 min, during which DAT+ neurons are in a reduced state, were analyzed in greater detail. In the graphs, means with standard deviation are superimposed on the scatter plots. In DAT+ neurons, a reduced state is observable after 120 min of treatment, as indicated by the mean and the standard deviation values, respectively. A minimum in SS/SH values is observed at 150 min, and a minimum in variance is observed after 180 min. No significant differences are observed in cortical neurons. (h) Frequency distribution graphs as a function of cellular redox state. As a reference, the value of the redox state possessed by the majority of neurons in untreated cultures is marked with gray (cortical) or black (DAT+) lines parallel to the y-axes. Shorter and wider curves indicate a heterogeneous redox state in the population of cells, whereas taller and narrower curves indicate homogeneous redox state. The rotenone-induced oxidation is more profound in DAT+ neurons, as indicated by the more pronounced changes in the frequency distribution. The red arrowhead indicates the narrow and tall peak observed during the reduced, clamped state (180 min). (To see this illustration in color the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertonline.com/ars).

In general, DAT+ neurons are more oxidized than cortical neurons (Fig. 3b, d, e, and Supplementary Fig. S2, p<0.001 for all time points, with the exception of the nonsignificant differences at 180 and 1200 min). Rotenone administration induced a multiphasic response, with alternating cycles of oxidation and reduction (Fig. 3b). Three peaks of oxidation were observed in DAT+ neurons (at 5, 15, and 45 min), and only two peaks in cortical neurons (5 and 15 min; Fig. 3b, arrowheads).

The variance of the cellular redox state in the populations under study represents a further major difference between DAT+ and cortical neuron redox homeostasis. The spread of the intracellular redox state values is significantly greater in DAT+ neurons, as indicated by the strikingly larger variance (Fig. 3c, significance was determined with Bartlett's test for equal variances p<0.0001), and by the larger standard deviation (Supplementary Fig. S3d, e). Both these statistical measures reflect the wider spread of values observed in the scatter plot (Fig. 3d, e). The differences in variance and in the redox spread were significant (p<0.0001) between the time-points of the time-course, and exhibited a multiphasic pattern, with two peaks (at 15 and 90 min) in DAT+ neurons (Fig. 3c) and a single peak at 30 min in cortical neurons (Fig. 3c).

In DAT+ neurons the major peak of oxidation was followed by a robust antioxidant response, after 180 min of treatment, which brought the redox state to a more reduced level than what was observed in control cultures (Fig. 3b–d, asterisk). Perhaps more interesting, at this time point, the redox state of the population was very homogeneous, with minimal spread, as shown in the scatter plot (Fig. 3d, arrowhead), and indicated by the very low variance value (Fig. 3c, arrowhead). We define this condition as “redox clamping.”

Finally, at the time-course endpoint, after 24 h (1440 min) of treatment, the redox state of DAT+ neurons was still significantly more reduced than their respective controls (Fig. 3d and Supplementary Fig. S3f, g), suggesting a sustained antioxidant response. Conversely, the endpoint redox state in cortical neurons was slightly more oxidized than the respective control (Fig. 3e and Supplementary Fig. S3g). Because no significant cell death was detected at this stage, this result supports the notion that cortical neurons can better tolerate intracellular oxidized states.

To better represent the distribution of the individual cells' redox states within the studied populations, we expressed the data according to frequency distribution plots (Fig. 3h). This form of representation plots on the y-axis the fraction of neurons (in percent) that are present at a certain redox state (x-axis); the shape of the curve provides a depiction of the distribution of the measures. In this plot—due to its mathematical construction—the total sum of the y-values is always constant, and equal to 100; therefore, taller curves are necessarily narrower, and vice versa. Tall and narrow curves represent populations with a homogeneous redox state, whereas wide and low curves correspond to populations with a wide redox state spread. Peaks represent values of the redox state in which the largest fraction of the neuronal population exists.

The distribution curves confirm that oxidation induced by rotenone is more pronounced in DAT+ neurons; in fact, during the time-course, the distribution curves become progressively wider (Fig. 3h), indicating that a large fraction of the population reaches states of higher oxidation. The climax is reached between 45 and 90 min. In cortical neurons, this effect is not as pronounced, even though a shift in the peak toward higher oxidation is detected (Fig. 3h). During the reduced state with low variance, which is observed after 180 min of treatment, the frequency distribution of DAT+ neurons is very narrow, confirming that the cellular population is very homogeneous in its redox state. Also, the frequency distribution curves confirm that the redox state of DAT+ neurons in their clamped state is more reduced than the redox state of the respective control (Fig. 3h, red arrowhead in the 180 min graph).

Finally, the distinctive redox response is not specific for rotenone treatment in that hydrogen peroxide treatment induces similar effects (Supplementary Fig. S3h, i).

The redox response observed in primary cultures is confirmed by studies in zebrafish larvae

The redox state of neurons in situ is profoundly influenced by the surrounding environment, which includes cross talk between neurons and glial cells. Therefore, we wanted to extend the observations gained studying in vitro dissociated cultures to an experimental model of higher biological complexity, where the investigation can be performed in intact physiological conditions. For this purpose, we used zebrafish larvae, which are transparent and therefore can be studied by fluorescence microscopy in whole-mount preparations, without loss of tissue integrity. In this setting, the penetration of the fluorescent dyes for the redox staining was ensured by mild permeabilization of the larvae during the fixation step (see Materials and Methods section). To track neuronal type unequivocally, we utilized transgenic animals expressing enhanced green fluorescent protein under either (i) an 11 kb fragment of the slc6a3 (dat) promoter, which expresses in neurons of the dopaminergic pretectal nucleus in addition to some nondopaminergic neurons in the adjacent midbrain (6) (Fig. 4a), or (ii) the pan-neuronal 12 kb eno2 promoter (Supplementary Fig. S4a) (7). These animals enabled us to identify DA neurons and non-DA neurons—which are identified as eno2:egfp-positive cells located in anatomical regions of the larvae that do not contain DA neurons—in whole-mount samples without using additional stains. We exposed larvae to rotenone (10 nM), and performed a time-course analysis of variations in cellular redox status in dopaminregic neurons of the pretectal region and compared the responses to nondopaminergic neurons. Surprisingly, the results were strikingly similar to those obtained in primary culture. In dopaminergic neurons, we observed a multiphasic response to rotenone, with three peaks of oxidation at 5, 15, and 90 min (Fig. 4b, arrowheads), and the spread in the redox values increased during the treatment (Fig. 4b, d). After 180 min of treatment, the intracellular redox state of DA neurons was in a reduced state with small variance (Fig. 4b, arrowhead). In non-DA neurons, the response was much less pronounced, similar to that observed in cortical neuronal cultures (Fig. 4c). At the end of the experimental time-course (24 h), dopaminergic neurons were in a reduced state compared with controls (Fig. 4b and Supplementary Fig. S4b), whereas nondopaminergic neurons did not show significantly different cellular redox state from controls (Fig. 4c and Supplementary Fig. S4c). In agreement with the observations obtained in primary cultures, the variance in redox state in DA neurons significantly increased during rotenone treatment, whereas this effect was not detected in non-DA neurons (Fig. 4d).

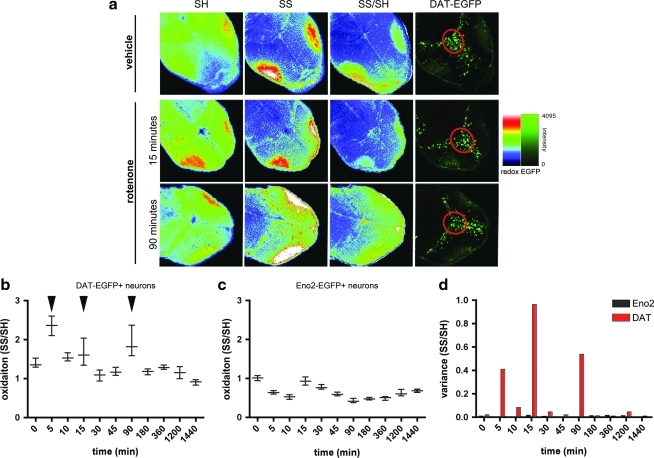

FIG. 4.

Redox time course in zebrafish embryo neurons treated with rotenone mirrors the findings in primary cultures. (a) Representative images of Tg(slc6a3[11kb]:egfp) transgenic zebrafish larvae stained for oxidized and reduced thiols. The image shows the oxidation levels in vehicle-treated larvae, and at two time points after rotenone treatment, when a peak of oxidation was detected. The pretectal nucleus of dopaminergic neurons (circled in red) was identified at the anterior end of the GFP+ cluster, and was used to delineate the region of interest in which the signal of the reduced and oxidized thiols was measured. (b) Time-course analysis of the variation of DA neurons' redox state following administration of 10 nM rotenone. The pattern is multiphasic, with three peaks of oxidation (black arrowheads). At the 180 min time point DA neurons are in a clamped, reduced state. Data are plotted as median with the interquartile range. (c) The fluctuations in the redox state in nondopaminergic neurons are less pronounced, with a single peak of oxidation at the 15 min time-point. Data are plotted as median with the interquartile range. In (b) and (c) medians are significantly different (p<0.001, Kruskal-Wallis test, followed by a Dunn's multiple comparison test). (d) The variance of the redox state in DA neurons is significantly higher than in non-DA neurons (p<0.001). At the time-points when oxidation peaks, the variance of DA neurons redox state is remarkably high. (To see this illustration in color the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertonline.com/ars).

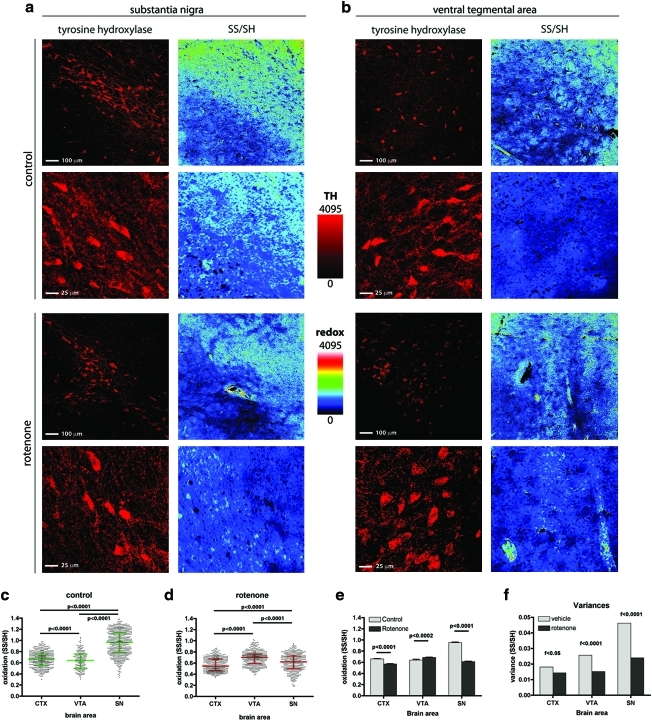

Redox analysis of rat brain sections indicates that DA neurons in the substantia nigra respond differently to oxidative challenge than those in the VTA

In the pathogenesis of PD, DA neurons in the SNpc degenerate more severely than DA neurons in the adjacent VTA, which are relatively spared (19, 30, 58). Importantly, such selectivity is reproduced in animal models of PD as well, where the pathogenesis is mimicked through the systemic administration of pro-oxidant compounds (9, 18, 37, 47). This suggests that DA neurons in different brain regions may manifest different degrees of tolerance to oxidative insults. We therefore compared the redox response elicited by rotenone in the DA neurons of the SNpc to the DA neurons of the VTA, examining the redox state in brain specimens from rotenone-treated rats. Since the present work is focused on the early redox response, we performed our investigations in animals treated only for 5 days, which were nonsymptomatic, and showed no evidence of striatal denervation upon TH immunostaining (data not shown). After 5 days of systemic rotenone treatment, DA neurons are still alive, and are likely utilizing antioxidant systems to cope with the oxidative insult. Therefore, this condition can be compared to the endpoint (24 h or 1440 min) of our previous time-course experiments, where we found DA neurons in a reduced state (Figs. 2d and 3b and Supplementary Fig. S3b, 3f) and did not observe any cell death. The redox histochemistry was performed in conjunction with TH staining in fresh cut slices from flash-frozen brains; the redox state was preserved by immediately blocking the slices' thiol groups with fluorescent alkylating agents (see the Materials and Methods section for detailed description). Under basal conditions, in vehicle-treated rats, we found that DA neurons in the SNpc were significantly more oxidized than both DA neurons in the VTA, and cortical neurons (Fig. 5c). The response of cortical neurons and DA neurons in the VTA was very mild in rotenone-treated rats; in contrast, DA neurons in the SNpc exhibited a robust reductive response (Fig. 5d, e). In our previous experiments, we observed a peculiar reductive clamping in DA neurons, which was reflected in a drastic decrease in the spread of the redox state, and therefore in the variance of the data sets. Since this effect was a unique feature of DA neurons, we sought to understand whether this particular response could be observed in the rat brain as well. The calculated variances indicate that rotenone induces a significant and striking decrease in the variance of the redox state in DA neurons of the SNpc, whereas it does so to only a lesser extent in the VTA and in cortical neurons (Fig. 5f). The redox clamping effect is also apparent as decreased spread in the scatter plot graphs (Fig. 5c, d). Overall, these results indicate that oxidative inputs to the mammalian brain induce effects of greater magnitude in DA neurons of the SNpc than in those of the VTA.

FIG. 5.

Rotenone induces region-specific alterations in neuronal redox state in the rat brain. Representative images of RHC applied to rat brain sections containing the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNpc) (a) or the ventral tegmental area (VTA) (b). The sections were counterstained for tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) to identify DA neurons. (c) Intracellular redox state of TH+ neurons in vehicle-treated rats. The basal intracellular redox state of DA neurons in the SNpc is more oxidized than that of DA neurons of the VTA or cortical neurons. (d) Intracellular redox state in rotenone-treated rats. (e) Direct comparison of the redox state levels in tissues from vehicle- (gray bars) or rotenone-treated (black bars) animals. Rotenone induces a robust response in DA neurons in the SNpc, which results in a more reduced intracellular redox state. DA neurons of the VTA, and cortical neurons react to a smaller extent. (f) Rotenone administration induces a decrease in the variance of the redox state values, which is analogous to the redox clamping observed in primary mesencephalic neurons, and zebrafish larvae. The magnitude of variance reduction is greater in the DA neurons of the SNpc. The decreased spread in redox state is also notable in the scatter plots (c, d), in which each dot represents an individual neuron. Variances are significantly different (p<0.001). (To see this illustration in color the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertonline.com/ars).

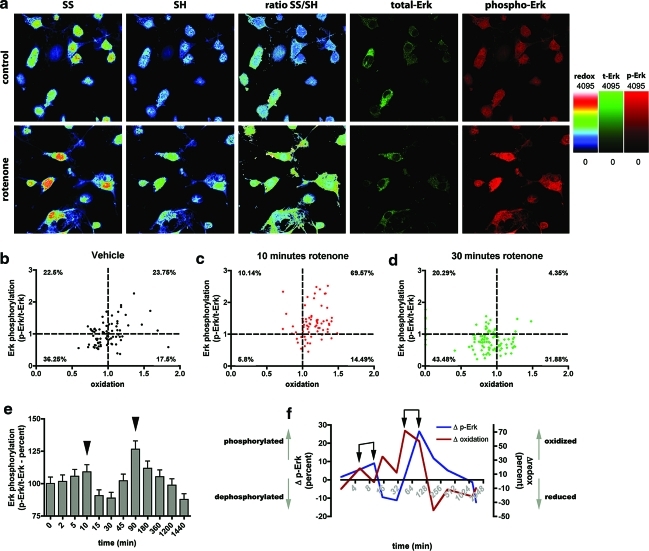

The variations in intracellular redox state precede and are synchronized with MAPK mediated signaling

Changes in redox state are associated and integrated with signaling processes. In particular, the MAPK pathways—including the Erk—are activated during oxidative stress (48) as well as in PD and models thereof (40, 64). The causal relationship between an oxidative insult and the phosphorylation of MAPKs is well established; however, studies directly comparing the dynamics of MAPK phosphorylation levels with associated fluctuations in intracellular redox state have been lacking thus far. In this regard, our RHC method could provide important insight into how the intracellular redox environment is integrated into the MAPK signaling cascades. Therefore, we applied our redox-histochemistry method to VM cultures, in combination with immunocytochemical staining for phosphorylated Erk1/2 (p-Erk1/2). This strategy allowed us to measure concurrently, in individual cells, the redox state, and the normalized levels of Erk phosphorylation (expressed as the signal ratio of p-Erk1/2 to total Erk1/2) (Fig. 6a). In a first set of experiments, we represented the data on scatter dot plots. To facilitate the visualization of the results, the graph has been divided into four quadrants by two perpendicular lines indicating the mean values of redox state (x-axis) and phosphorylation (y-axis) of the control cultures (Fig. 6b–d). In control cultures the data points are equally divided among the four quadrants (Fig. 6b). After 10 min of rotenone exposure we found a transient increase in oxidation—confirming our previous observations—and this correlated with high levels of Erk1/2 phosphorylation. In fact, 69.57% of the data-points were found the top-right portion of the graph, indicating high-oxidation and high phosphorylation states (Fig. 6c). This phase was followed by a reductive phase, where 43.48% of the cells are in a reduced state with low p-Erk1/2 (Fig. 6d, lower-left portion of the graph), and only 4.35% of the cells occupied the top-right portion of the graph. To investigate in greater detail the association between Erk1/2 activation and redox state, we performed a full time-course analysis and found, just as the variations in the redox state are multiphasic, Erk1/2 phosphorylation is likewise multiphasic, with a minor peak at 10 min and a major peak at 90 min (Fig. 6e, arrowheads). Interestingly, these peaks follow the minor and the major peak of oxidation, respectively (Fig. 6f, arrows). No significant changes in Erk phosphorylation were observed in cortical neuron cultures.

FIG. 6.

Time-dependent variation in cellular redox state correlates with variations in ERK signaling. (a) Representative images of RHC applied in combination with phosphorylated extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1/2 (p-Erk1/2) and total Erk1/2 (t-Erk1/2) labeling in VM primary cultures. Rotenone induces an increase in oxidation—as indicated by the SS/SH ratio—as well as an increase in p-Erk1/2 (red channel). (b–d) Scatter plot graphs show that p-Erk1/2 levels correlate with the intracellular redox state. The dashed lines mark the mean values of the redox state (vertical) and of Erk1/2 phosphorylation (horizontal) in the vehicle-treated sample, and define four quadrants in the plot. The graphs depict that rotenone treatment induces simultaneous variations in p-Erk1/2 and the redox state. (c) Ten minutes of rotenone administration induces increases in p-Erk1/2 and in oxidation (69.57% of the cells are in the top-right quadrant). (d) After 30 min, the majority of the cells are in a reduced state, with low levels of p-Erk1/2 (43.48% of the cells in the bottom-left quadrant). (e) Time-course analysis in primary rat VM neurons indicates that rotenone induction of Erk1/2 phosphorylation is multiphasic, with peaks at 10 and 90 min (arrowheads). (f) Variations in p-Erk1/2 and intracellular redox state during rotenone treatment in primary rat VM neurons. The control is set equal to zero in both cases, and the graph represents variations as percent of control during the treatment. Peaks in oxidation (red line) precede those in p-Erk1/2 (blue line), SD is indicated by the pairs of black arrows. Means are significantly different (p<0.001). (To see this illustration in color the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertonline.com/ars).

In conclusion, these results highlight a temporal correlation between Erk phosphorylation and the intracellular redox state (Fig. 6f), and indicate that peaks in oxidation precede the activation of the MAPKs signaling pathways.

Discussion

In this study, we investigated the neuronal redox response elicited by nonlethal amounts of ROS using various in vitro and in vivo systems. Since our interest was to examine small changes in the intracellular redox state, which are associated with signaling events, it was necessary to develop a new imaging approach, which measures the redox state as the ratio between oxidized and reduced thiols. The technique accurately and sensitively detects mild changes in intracellular redox state in situ.

In agreement with the particular physiology of DA neurons, the redox response observed in these cells is distinctive in many respects. Under basal conditions, and in untreated samples, the intracellular redox state is more oxidized in DA neurons than in non-DA neurons. The redox alterations elicited by pro-oxidants are of greater magnitude in DA neurons, even though some of these cells do not respond, as demonstrated by the changes in variance. After cycles of oxidation and reduction, DA neurons are forced into a reduced redox state, a more homogeneous condition in which the entire population of DA neurons shows very similar intracellular redox states. The reduced state is persistent, and is maintained until the endpoint of our time-course. Importantly, the reductive response was observed only in SNpc DA neurons, and not in VTA DA neurons. Finally, redox variations are synchronized with signaling, and cycles of oxidation and reduction anticipate, respectively, phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of the MAPK member Erk1/2.

The technique

The brain is characterized by extraordinary histological complexity. Likely, the intracellular redox state and its homeostasis differ among cell types. In this respect, DA neurons are paradigmatic: they have been hypothesized to be intrinsically prone to oxidation because of their physiology, and they have been shown to be particularly vulnerable to pro-oxidant xenobiotics (14, 15, 32, 33). For these reasons, redox studies should be performed at the level of individual cells; however, there is a general lack of techniques to perform single-cell redox analyses. Most of the available tools rely on modified redox-sensitive versions of fluorescent proteins (rsFPs), which are used for live imaging studies. Certainly, these approaches are extremely valuable, despite some weaknesses. These sensors measure the redox state of the couple GSH/GSSG, which represents just one aspect of the total intracellular redox state (49). In fact, emerging evidence clearly indicates that intracellular redox state is not solely governed by GSH/GSSG, and that protein thiols provide an essential contribution as well (1, 41, 57). A further limitation of rsFPs-based redox imaging methods is that the use of rsFPs in association with other fluorescent markers is rarely achievable. It could be possible to use expression vectors for markers for the cell types (e.g., reporters under the DAT promoter to recognize DA neurons) for cotransfection with rsFPs. Nevertheless, it would be impossible to use markers for signaling events such as phosphorylation. Because redox state and signaling are deeply interrelated, this latter issue constitutes a serious limitation for rsFPs-based methods. Also, the live imaging approach—despite its indisputable usefulness—suffers additional limitations. Live imaging experiments are not always easy to perform: data acquisition is time consuming, and studies in deep areas of the brain (such as the SNpc) cannot be performed. Finally, rsFPs emit in a very limited range of wavelengths, in the green–yellow region. This feature could represent an issue when several cellular functions are measured in the same imaging session, using multiple fluorescent probes.

To circumvent these limitations and implement the panel of available redox techniques, we developed an imaging protocol to determine the intracellular redox state. The protocol is based on maleimide derivatization of thiols, an approach that has already been shown to be specific and applicable to histological preparations (46). The ratiometric labeling of thiols to determine the redox state has already been used for proteomic studies; however, to the best of our knowledge, it has never been applied to histological studies (38, 39, 41). Unlike rsFPs, our method is not confined to the GSH/GSSG redox couple, and instead measures the total thiol redox state. It can be used in combination with several other markers, whose number solely depends on the channels available in the emission detecting apparatus of the acquiring instrument. The technique can be applied to different types of specimen and thus is extremely versatile; we successfully used it in cell cultures, zebrafish larvae, and tissue sections from mammalian brains. Finally, maleimide can be conjugated to a great variety of fluorophores, and therefore the wavelength of the thiol modifying tags can be chosen according to experimental needs.

The measure of the intracellular redox state provided by RHC is not bound to a particular redox couple and it instead measures the general redox state of the cell, as indicated by the experiments in which RHC was paralleled by assays to determine the GSH/GSSG and pr-SH/pr-SS redox state (Fig. 1). In these studies, PC12 cells and primary VM cultures provide very different outcomes (Supplementary Fig. S1c, d), which can be explained, at least in part, by the different nature of these cultures and by some fundamental technical differences between RHC and GSH/GSSG or prSH/pr-SS assays. In particular, the GSH and pr-SH redox assays measure redox levels in a mixed sample (i.e., cellular homogenate) deriving from and a heterogeneous population of cells (i.e., glia and different neuronal types), and therefore the provided measure is an average value reflecting the complexity of the specimen. In contrast, RHC measures the redox state in individual cells and here it was used to analyze specifically DA neurons; in this case, the measure concerns a sample of relatively small complexity. When the specimen being examined is a relatively homogeneous population—such as clonal cultures—the measures of RHC might converge with those obtained analyzing cell homogenates, as observed in PC12 cells. On the contrary, in a heterogeneous population such as primary VM cultures (which contain various neuronal and glial cell types), these measures could vary substantially. Nevertheless, the experiments in Supplementary Figures S3c and 3d serve to demonstrate that RHC is not bound to a specific redox couple in all cell types, and thus it measures the redox state of total thiols. It is quite clear that there is no unique and universal assortment of redox couples to control homeostasis and some cell types may rely on certain redox couples more than others. Thus, the redox couples contributing to the total thiol redox state, and to the RHC signal, will depend upon the specific biological sample under study.

In its present version, the method does not discriminate nitrosothiols (-SNO), as at this stage, our investigations deliberately focused on the redox couple thiols/disulfide. However, we envision that the technique could be easily adapted to study these important modifications, using different reducing agents, such as ascorbate, that specifically target SNO (31).

As with any novel technique, our redox histochemistry method requires further improvement and validation, particularly with respect to its ability to distinguish compartmental redox status at the subcellular level. Among the various experimental avenues to do so, we anticipate that investigating the following issues in greater detail—eventually, varying timing and concentrations of reagents in a systematic manner—will possibly improve the method. First, milder yet effective detergents or fixatives could be used in the initial fixation/permeabilization procedure to further preserve the integrity of subcellular structures and to retain low-molecular-weight molecules (e.g., GSH). The technique can be refined using membrane-permeable maleimide-conjugated fluorophores, which could block the redox state and obviate membrane permeabilization. Second, detergents that improve the access of the reducing agent to disulfides, thereby achieving a more complete reduction, could potentially improve the labeling. Third, further studies may identify alkylating fluorophores with minimal sterical hindrance and greater hydrophobicity, which would ensure superior ability to access and label buried cys residues; in fact, we have already demonstrated that, under nondenaturing conditions, some maleimide dyes modify thiols more efficiently (46). Fourth, in tissue analyses, the morphology would greatly benefit from prefixation steps, eventually using membrane-permeable maleimide dyes, before tissue sectioning. Finally, future studies should compare the results provided by our method with those generated with other available tools such as rsFPs, or in combination with genetic manipulation of pathways that are relevant for redox control (e.g., glutaredoxins or thioredoxins).

ROS generation

We measured rotenone-induced ROS production using two different approaches, which provided different results. The use of the mitoSOX probe, which is specific for mitochondrial superoxide, demonstrated that low (10 nM), not high (100 nM), doses of rotenone generate ROS at a significantly higher rate in VM cultures as compared with CTX cultures. Conversely, the less specific probe CM-H2-DCFDA did not highlight any significant difference between the two types of cultures. This discrepancy is only apparent. In fact, rotenone is well known to induce superoxide production in mitochondria (53), and thus mitoSOX allows the measure of the specific ROS induced by rotenone in close proximity its site of generation. This is a great advantage in terms of sensitivity, because the diffusion ability of ROS is severely limited by their reactivity (62) and therefore measures in close proximity of the site of generation, such as those performed with mitoSOX, will likely provide a signal of higher intensity. However, it should be noted that ROS other than O2− have a better reactivity with thiols (62) and therefore might exert greater influence on disulfide formation. In this respect, CM-H2-DCFDA provides interesting insights because it is not limited to O2− and thus provides a more general estimate of ROS. Moreover, several proteins responsible for redox signaling, including members of the MAPK family such as those studied in this work, are localized in the cytoplasm; therefore, the measure accomplished with CM-H2-DCFDA, which is not confined to mitochondria, provides an estimate of the amount of ROS that will reach the cytoplasmic effectors of the redox-signaling cascade. In this respect, the measure provided by the RHC is more sensitive than that of CM-H2-DCFDA. This evidence can be explained, at least in part, by the different nature of the measured entities. Thiol/disulfide couples act as molecular switches, influencing the properties and localization of modified proteins; for these events to occur, chemical stability is required. In addition, thiol oxidation occurs on proteins and GSH, which are highly expressed in the cell and can exceed stable concentrations of 10−2 M. Conversely, ROS are intrinsically transient and, because of the limited diffusion ability, very elusive; the concentration can also constitute an issue as the rate of rotenone induced ROS production has been estimate in the order of 10−9mol·mg−1·min−1 (53). Finally, the molecular mechanisms responsible for the higher production of ROS in VM neurons are unknown and could be attributed to intrinsic features of DA neurons' mitochondria. Certainly, further studies are necessary to specifically address this important issue.

Higher oxidation in SNpc DA neurons

The more oxidized intracellular redox state observed in DA neurons of the SNpc under basal conditions may be explained by their particular physiology. In fact, these neurons govern their pacemaking activity—which is spontaneous and does not require synaptic inputs—using L-type Ca2+ channels (52, 55). This mechanism appears to be specific for SNpc DA neurons as DA neurons in other regions (15, 54), as well as other neuronal types (8), do not rely upon Ca2+ and mostly use Na+ to generate their action potentials. Therefore, in SNpc DA neurons, each action potential is associated with a robust Ca2+ influx into the cytosol. The spontaneous and rhythmic nature of the pacemaking activity could lead to elevated cytosolic Ca2+ concentrations, which could be harmful for the cell. This undesirable condition is prevented by extrusion of Ca2+, and its uptake by ER and mitochondria. However, this protective action comes at a cost as the internalization of Ca2+ into the mitochondrial matrix neutralizes the transmembrane electromotive proton gradient (ΔΨ). To preserve ΔΨ—which is essential for ATP production—mitochondria need to augment proton pumping by the respiratory complexes, which is achieved by increasing electron transport. Intrinsic to this process is an increased production of ROS. Over time, the continuous activity of SNpc DA neurons may lead to increased ROS levels and thus to a more oxidized intracellular redox state (14). In line with this hypothesis, recently published work demonstrated how the L-type Ca2+ channel blocker isradipine reduces oxidation in DA neurons (27). Interestingly, in the same study, the authors demonstrated that SNpc DA neurons are more oxidized than those in the VTA. This evidence—which was obtained by an approach different from ours, based on rsFPs—strongly corroborates our findings obtained in rat brain (Fig. 5).

The particular mitochondrial physiology, influenced by a particular use of Ca2+, could also provide a partial explanation for the amplified response observed in DA neurons, when compared to cortical neurons. In fact, the higher rate of ROS production observed in rotenone-challenged VM cultures is not sufficient to fully explain the DA neurons redox response. In fact, the overall thiol redox state is the result of the combined action of ROS and the subsequent antioxidants defenses. This argument is also supported by the evidence that H2O2 treated DA neurons exhibit an amplified response (Supplementary Fig. S3h, i) despite that fact that no differences in H2O2-mediated ROS production could be detected with CM-H2-DCFDA (Supplementary Fig. S3a, b). Further studies will be necessary to evaluate the contribution of these two elements to the redox state in DA versus non-DA neurons.

Spread in redox state and variance

The electrophysiological properties of SNpc DA neurons may also explain our observation that only a subset of DA neurons respond to pro-oxidant inputs; this is evident as the variance in the intracellular redox state increases during treatment. In fact, previous and elegant studies showed that DA neurons in the SNpc differ in their sensitivity to rotenone. Rotenone administration—in concentrations that are comparable to what was used in our studies—leads to cell depolarization through the activation of ATP-sensitive potassium channels (K-ATP). Interestingly, K-ATP activation is not homogeneous within the population of DA neurons. The differences between responders and non-responders might be ascribed to the particular assortment in the subunits composing the channel (5, 42, 44). Importantly, variations in the intracellular redox state anticipate and regulate the activation of K-ATP channels. In fact, these proteins have redox-sensitive thiols (16) and their conductance is modulated by ROS—possibly hydrogen peroxide—which can open and activate the channel even in the presence of high levels of ATP (5). K-ATP channel activation has been directly correlated with the pathogenesis of PD (43); in this scenario the sustained reductive response we observed in SNpc DA neurons might reflect the countermeasure of these cells to prevent redox imbalance from initiating pathogenic cascades.

Redox signaling and Erk phosphorylation

Thiol oxidation is the principal mechanism integrating intracellular redox state with signaling pathways (62). To understand the correlation between these two elements in our experimental system, we performed single-cell imaging to measure simultaneously the redox state and the phosphorylation of Erk1/2, a member of the MAPK pathway that is known to promote cell survival and is activated during redox imbalance (40, 48). In our experimental system, we observed two distinct peaks in Erk1/2 phosphorylation; importantly, these data are in agreement with previous findings showing that the PD-related toxin, 6-hydroxydopamine, induces a bi-phasic activation of Erk1/2 (40). The data showing that oxidation anticipates Erk1/2 phosphorylation and that these events are synchronized (Fig. 6f) strongly support the concept that the intracellular redox state regulates this signaling pathway.

The oscillatory response

Further studies will be required to understand the redox systems governing the alternation of oxidation and reduction cycles initiated by pro-oxidant administration. However, it is reasonable to hypothesize that this trend reflects the sequential engagement of different anti-oxidant pools. In such a scenario, a peak in oxidation would reflect the exhaustion of the reductive capacity of the redox pool in use; the subsequent reduction indicates the intervention of a new redox pool. Likely, during the first cycle, which is observed within minutes of toxin administration, the cell deploys the readily available antioxidant resources (e.g., GSH). The second cycle, which is anticipated by a minor peak in Erk phosphorylation, could involve moderate transcriptional activity to generate further antioxidant resources. The final cycle, during which the highest peak of oxidation and the sharp and homogeneous reduction in redox state variance (redox clamping) are observed, likely involves a sustained transcription-based antioxidant response, as supported by the robust phosphorylation of Erk1/2. Indeed, Erk1/2 is known to activate transcription factors under oxidative conditions, leading to cytoprotection (40).

The overall importance of redox studies

The redox state of thiols exerts a profound effect on the physiology of neurons; for instance, it regulates fundamental processes such as synaptic plasticity (11) and controls the conductance of several ion channels involved in neuronal excitability (13, 24). Additionally, thiol oxidation has been involved in PD pathogenic events such as K-ATP-mediated neuronal depolarization (3, 16, 43) and transferring-mediated iron accumulation (45). Therefore, investigating the variations in thiol redox state and the associated signaling events will provide crucial information for understanding the healthy and diseased brain. Importantly, the intracellular redox state both depends upon and influences the general physiology of the cell. Here we provide a novel, versatile, and sensitive method to carry out these kinds of studies. Importantly, this method is compatible with simultaneous analysis of signaling activation in the same cell, and can be used across a wide range of in vitro and in vivo systems. Of particular clinical importance, the method will also be useful in assessing the effects of antioxidant therapies, which has long been considered an appealing strategy to balance the redox alterations observed during neurodegeneration. In such a context, this redox imaging method will allow investigators to determine the drug's effects directly in the neuronal types that are specifically affected in the neurological disease under study.

Supplementary Material

Abbreviations Used

- BSO

buthionine sulphoximine

- CM

chloromethyl

- cys

cysteine

- DA

dopamine

- DAT

dopamine transporter

- DCFDA

2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate

- EDTA

ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid

- Erk

extracellular signal-regulated kinases

- GDNF

glial cell-derived neurotrophic factor

- GSH

glutathione

- GSSG

oxidized glutathione

- HBSS

Hanks' Buffered Salt Solution

- MAP2

microtubule associated protein 2

- MAPK

mitogen activated protein kinase

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- p-Erk1/2

phosphorylated extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1/2

- PFA

paraformaldehyde

- pr-SH

protein thiol

- RHC

redox immunohistochemistry

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- rsFPs

redox-sensitive versions of fluorescent proteins

- SDS

sodium dodecyl sulfate

- SNpc

substantia nigra pars compacta

- TCEP

tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine

- t-Erk1/2

total extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1/2

- TH

tyrosine hydroxylase

- TRAIL

TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand

- VM

ventral mesencephalic

- VTA

ventral tegmental area

Acknowledgments

P.G.M. was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (K99-ES016352), an administrative supplement under the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 from the NIEHS, a Marie Curie International Reintegration Grant, and by the Netherlands Genomics Initiative (NGI/NWO 05040202). This work was also supported by NIH grant 1P01NS059806 (J.T.G.), American Parkinson Disease Center for Advanced Research at the University of Pittsburgh (J.T.G.), and NIH grant 1F30ES019376 (M.P.H.). V.T. is postdoctoral fellow from the Ministry of Education and Science, Madrid, Spain (Fulbright Fellowship).

Author Disclosure Statement

The authors have no financial conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Adimora NJ. Jones DP. Kemp ML. A model of redox kinetics implicates the thiol proteome in cellular hydrogen peroxide responses. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2010;13:731–743. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alam M. Schmidt WJ. Rotenone destroys dopaminergic neurons and induces parkinsonian symptoms in rats. Behav Brain Res. 2002;136:317–324. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(02)00180-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anantharam V. Lehrmann E. Kanthasamy A. Yang Y. Banerjee P. Becker KG. Freed WJ. Kanthasamy AG. Microarray analysis of oxidative stress regulated genes in mesencephalic dopaminergic neuronal cells: relevance to oxidative damage in Parkinson's disease. Neurochem Int. 2007;50:834–847. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2007.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Antunes F. Cadenas E. Estimation of H2O2 gradients across biomembranes. FEBS Lett. 2000;475:121–126. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)01638-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Avshalumov MV. Chen BT. Koós T. Tepper JM. Rice ME. Endogenous hydrogen peroxide regulates the excitability of midbrain dopamine neurons via ATP-sensitive potassium channels. J Neurosci. 2005;25:4222–4231. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4701-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bai Q. Burton EA. Cis-acting elements responsible for dopaminergic neuron-specific expression of zebrafish slc6a3 (dopamine transporter) in vivo are located remote from the transcriptional start site. Neuroscience. 2009;164:1138–1151. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bai Q. Garver JA. Hukriede NA. Burton EA. Generation of a transgenic zebrafish model of Tauopathy using a novel promoter element derived from the zebrafish eno2 gene. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:6501–6516. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bean BP. The action potential in mammalian central neurons. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8:451–465. doi: 10.1038/nrn2148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Betarbet R. Sherer TB. MacKenzie G. Garcia-Osuna M. Panov AV. Greenamyre JT. Chronic systemic pesticide exposure reproduces features of Parkinson's disease. Nat Neurosci. 2000;3:1301–1306. doi: 10.1038/81834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Björklund A. Dunnett SB. Dopamine neuron systems in the brain: an update. Trends Neurosci. 2007;30:194–202. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2007.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bodhinathan K. Kumar A. Foster TC. Intracellular redox state alters NMDA receptor response during aging through Ca2+ /calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. J Neurosci. 2010;30:1914–1924. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5485-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bonci A. Grillner P. Mercuri NB. Bernardi G. L-Type calcium channels mediate a slow excitatory synaptic transmission in rat midbrain dopaminergic neurons. J Neurosci. 1998;18:6693–703. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-17-06693.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cai S-Q. Sesti F. Oxidation of a potassium channel causes progressive sensory function loss during aging. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:611–617. doi: 10.1038/nn.2291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chan CS. Gertler TS. Surmeier DJ. A molecular basis for the increased vulnerability of substantia nigra dopamine neurons in aging and Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 2010;25(Suppl 1):S63–S70. doi: 10.1002/mds.22801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]