Abstract

Antigen-specific immunotherapy and vascular disrupting agents, such as 5,6-dimethylxanthenone-4-acetic acid (DMXAA), have emerged as attractive approaches for the treatment of cancers. In the current study, we tested the combination of DMXAA treatment with therapeutic human papillomavirus type 16 (HPV-16) E7 peptide-based vaccination for their ability to generate E7-specific CD8+ T-cell immune responses, as well as their ability to control E7-expressing tumors in a subcutaneous and a cervicovaginal tumor model. We found that the combination of DMXAA treatment with E7 long peptide (amino acids 43–62) vaccination mixed with polyriboinosinic:polyribocytidylic generated significantly stronger E7-specific CD8+ T-cell immune responses and antitumor effects compared with treatment with DMXAA alone or HPV peptide vaccination alone in the subcutaneous model. Additionally, we found that the DMXAA-mediated enhancement of E7-specific CD8+ T-cell immune responses generated by the therapeutic HPV peptide-based vaccine was dependent on the timing of administration of DMXAA. Treatment with DMXAA in tumor-bearing mice was also shown to lead to increased dendritic cell maturation and increased production of inflammatory cytokines in the tumor. Furthermore, we observed that the combination of DMXAA with HPV-16 E7 peptide vaccination generated a significant enhancement in the antitumor effects in the cervicovaginal TC-1 tumor growth model, which closely resembles the tumor microenvironment of cervical cancer. Taken together, our data demonstrated that administration of the vascular disrupting agent, DMXAA, enhances therapeutic HPV vaccine-induced cytotoxic T-lymphocyte responses and antitumor effects against E7-expressing tumors in two different locations. Our study has significant implications for future clinical translation.

Vascular disrupting agents such as 5,6-dimethylxanthenone-4-acetic acid (DMXAA) have emerged as a new class of potential anticancer drugs that selectively destroy the established tumor vasculature and shut down blood supply to solid tumors. In this study, Zeng and colleagues test the combination of DMXAA treatment with E7 long peptide vaccination mixed with poly(I:C) to enhance cellular immunity against E7-expressing tumors in mice.

Introduction

Cervical cancer is the second leading cause of cancer deaths in women worldwide (Parkin et al., 2005), with approximately 11,982 cases in the United States and 3,976 deaths annually (U.S. Cancer Statistics Working Group, 2010). It is now clear that cervical cancer is attributed to infection with a high-risk type of human papillomavirus (HPV) (Walboomers et al., 1999; Bosch et al., 2002). Among the high-risk types, HPV type 16 (HPV-16) is the most common, accounting for around 50% of invasive cervical cancers worldwide. The role of HPV as the necessary causative agent of cervical carcinogenesis provides the opportunity to control cervical cancer through effective vaccination against HPV.

Currently, the two commercial preventive HPV vaccines have been shown to effectively prevent persistent infection and associated disease by the induction of neutralizing antibodies against the L1 capsid proteins of HPV-16 and HPV-18 (Harper et al., 2004, 2006; Paavonen et al., 2009; for review, see Harper, 2009). However, these preventive vaccines exert no therapeutic effects (Garland et al., 2007; Hildesheim et al., 2007). In contrast to the antibody responses elicited by preventive HPV vaccines, therapeutic HPV vaccines aim to generate cell-mediated adaptive T-cell immunity for direct killing of virus-infected cells. HPV E6 and E7 oncoproteins represent potentially ideal targets for therapeutic HPV vaccine development, as E6 and E7 are constitutively expressed in HPV-infected cells. Hence, immunotherapy capable of inducing robust E6/E7-specific CD8+ T-cell immunity is highly desirable for eradication of established HPV-associated infection.

Peptide-based therapeutic HPV vaccines have emerged as an attractive form of therapeutic HPV vaccination due to stability, safety, and ease of production (for reviews, see Roden and Wu, 2003; Hung et al., 2008). However, they suffer from low immunogenicity and are limited by the polymorphic nature of human leukocyte antigen (HLA) molecules. The need to identify specific immunogenic epitopes of HPV antigens for many different HLA haplotypes may make it difficult to produce a peptide-based vaccine that will cover the whole population, making it impractical for large-scale vaccination treatments.

Recently, overlapping long peptides have renewed interest in therapeutic HPV peptide-based vaccines (for review, see Melief and van der Burg, 2008). Overlapping long peptides can circumvent the obstacle of MHC restriction by broadening the range of antigenic epitopes through inclusion of immunogenic peptides or peptides that direct CD4+ T-helper or CD8+ cytotoxic immune responses. In animal models, vaccination with HPV-16 E7 long peptides with adjuvants was shown to generate antigen-specific CD8+ T-cell immune responses, translating to eradication of established HPV-16+ tumors in vaccinated mice (Zwaveling et al., 2002). Preclinical studies have also shown that a cottontail rabbit papillomavirus (CRPV) E6/E7 long peptide vaccine suppressed CRPV-induced skin papillomas and generated HPV-16 E6- and E7-specific T-cell immune responses in vaccinated rabbits (Vambutas et al., 2005). E6 and E7 overlapping peptides have also shown significant E6/E7-specific T-cell responses in patients with HPV-associated lesions (Kenter et al., 2008, 2009; Welters et al., 2008). Thus, promising data for the use of overlapping peptides has renewed enthusiasm for therapeutic HPV E6/E7 peptide-based vaccines. It has been shown that the antitumor immune responses against a peptide-based vaccine can be enhanced using polyriboinosinic:polyribocytidylic acid [poly(I:C)]. Studies have shown that E7 peptide vaccines mixed with poly(I:C) induced strong E7-specific CD8+ T-cell immune responses and caused significant therapeutic antitumor effects against E7-expressing murine tumors (Cui and Qiu, 2006). Poly(I:C) has also been used to successfully enhance the HPV-specific immune responses in a rhesus macaque model (Stahl-Hennig et al., 2009). Thus, vaccination with E7 long peptide-based therapeutic HPV vaccines mixed with adjuvants such as poly(I:C) represents a potentially promising approach for the control of cervical cancer. However, the control of established tumors may require additional therapeutic approaches in addition to peptide-based therapeutic HPV vaccines.

Vascular disrupting agents such as 5,6-dimethylxanthenone-4-acetic acid (DMXAA) have emerged as a new class of potential anticancer drugs that selectively destroy the established tumor vasculature and shut down blood supply to solid tumors, causing extensive tumor cell necrosis (for reviews, see Baguley, 2003; Cai, 2007). DMXAA is a synthetic flavonoid that induces the production of local cytokines, including tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α). DMXAA has been shown to induce antitumor effects in animal models, as well as in clinical trials, especially in combination with established treatment such as chemotherapy (McKeage et al., 2009; Head and Jameson, 2010).

In the current study, we aim to test the combination of DMXAA treatment with E7 long peptide vaccination mixed with poly(I:C) to enhance the E7-specific CD8+ T-cell immune responses and antitumor effects against E7-expressing tumors in a subcutaneous tumor model, as well as a cervicovaginal tumor model. We found that the coadministration of DMXAA significantly enhanced the E7-specific CD8+ T-cell immune responses, as well as the therapeutic antitumor effects against TC-1 tumors generated by E7 long peptide vaccination in both tumor models. The clinical implications of the current study are discussed.

Materials and Methods

Drug, peptide, cells, and mice

DMXAA (Sigma–Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was reconstituted with 5% NaHCO3 to the concentration of 2 mg/ml and kept at −80°C in the refrigerator. The E7 peptide [amino acids (aa) 43–62] was constructed in our lab at a purity of ≥70%. Poly(I:C) was purchased from Sigma (Sigma–Aldrich) and diluted with PBS into 1 mg/ml stock before operating. The production and maintenance of TC-1 cells (Lin et al., 1996) and TC-1/luciferase (Huang et al., 2007) have been described previously. All of the mice were used in compliance with institutional animal health care regulations, and all animal experimental procedures were approved by the Johns Hopkins Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Intracellular cytokine staining and flow cytometry analysis

Splenocytes were harvested from mice (five per group) 1 week after the last vaccination. Prior to intracellular cytokine staining, 5 × 106 pooled splenocytes/ml from each vaccination group were incubated for 16 hr with 1 μl/ml E7 epitope (aa 49–57). To detect E7-specific CD81 (CD8+) T-cell precursor cell responses, CD81 (CD8+) cytotoxic T-lymphocyte (CTL) epitopes aa 49–57 and aa 30–67 were used, respectively. Golgistop (Pharmingen, San Diego, CA) was added 6 hr before the cells were harvested from the culture. Cells were then washed once in FACScan buffer and stained with phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated monoclonal rat anti-mouse CD8 antibody (Pharmingen). Cells were subjected to intracellular cytokine staining using the Cytofix/Cytoperm kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Pharmingen) as described in our previous studies (Hung et al., 2001; Kim et al., 2004). Analysis was performed on a FACScan with CELLQuest software (Becton Dickinson Immunocytometry Systems, Mountain View, CA).

In vivo imaging system

Mice were imaged with the IVIS 200 system (Xenogen Corp., Alameda, CA) at different time points for monitoring the therapeutic effects of the various treatments. The bioluminescence signals were analyzed by using the Living Image software (Xenogen).

In vivo subcutaneous tumor treatment experiments

For the tumor treatment experiments, C57BL/6 mice (five per group) were challenged with 1 × 105 TC-1 tumor cells per mouse by subcutaneous injection into the right flank. Mice were immunized with 10 μg of peptide per mouse [E7 (aa 43–62), 2.5 μg/μl, dissolved in 10 μg of poly(I:C) together with PBS to the amount of 100 μl] twice with a 1-week interval. The mice that were treated with peptide vaccine had their abdomens shaved before vaccination. DMXAA (dissolved in 5% NaHCO3) was administered via intraperitoneal injection at the dose of 20 μg/g of body weight, as specified in Figs. 1 and 4. Based on tumor perfusion studies in previous publications using a similar dose and route of administration of DMXAA (Wang et al., 2009), the DMXAA concentration in the tumor would be approximately 100 mM at 5 hr after treatment with DMXAA. A group of tumor-challenged mice with no treatment was used as the control group. Tumor growth was monitored by visual inspection and palpation and checked with the Vernier caliper twice weekly as described previously (Hung et al., 2001). Tumor volumes were estimated using the formula V (mm3) = 3.14 × [largest diameter × (perpendicular diameter)2]/6.

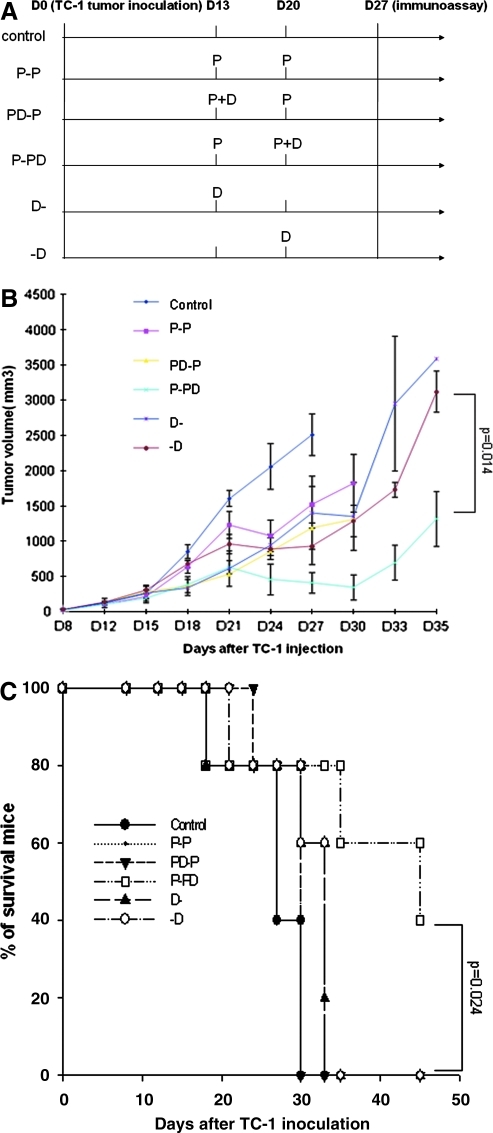

FIG. 1.

In vivo tumor treatment experiments. (A) Schematic diagram of the treatment regimen of E7 peptide vaccine and/or DMXAA. Groups of C57BL/6 mice (five per group) were subcutaneously challenged with 1 × 105 TC-1 tumor cells per mouse on day 0. The peptide vaccine is designated as P, and the DMXAA treatment is designated as D. Thirteen days after tumor challenge, mice of P-P, PD-P, and P-PD groups were immunized with 10 μg of peptide per mouse [E7 (aa 43–62), 2.5 μg/μl, dissolved in 10 μg of poly(I:C) together with PBS to the amount of 100 μl] twice with a 1-week interval. The PD-P and (D-) groups were treated with intraperitoneal injection of DMXAA (dissolved in 5% NaHCO3) at the dose of 20 μg/g of body weight) on day 13, whereas P-PD and (-D) groups were treated on day 20. A group of tumor-challenged mice with no treatment was used as the control group. Mice were monitored for evidence of tumor growth by inspection and palpation, and tumor size was measured twice a week starting from day 8 after tumor challenge. (B) Line graph depicting the tumor volume in TC-1 tumor-bearing mice treated with E7 peptide vaccine with or without DMXAA (means ± SE) (p = 0.014). (C) Kaplan–Meier survival analysis of TC-1 tumor-bearing mice treated with E7 peptide vaccine with or without DMXAA (p = 0.024). Data shown are representative of two experiments performed. Color images available online at www.liebertonline.com/hum.

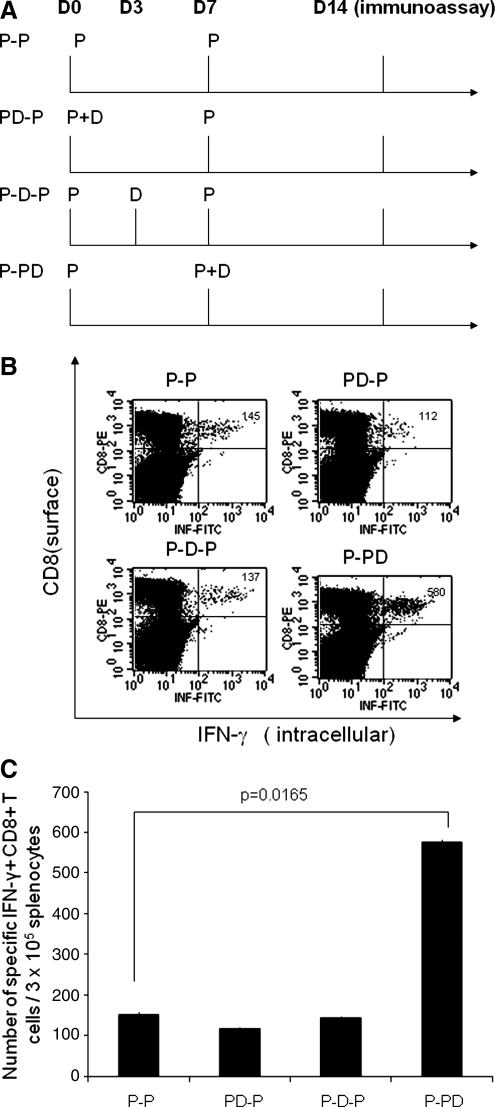

FIG. 4.

Intracellular cytokine staining followed by flow cytometry analysis to determine the number of E7-specific CD8+ T cells in naive mice treated with the E7 peptide vaccine with or without DMXAA. (A) Schematic diagram of the immunization regimen of the E7 long peptide vaccine and/or DMXAA. Groups of C57BL/6 mice (five per group) were injected subcutaneously with 10 μg of the E7 peptide vaccine [E7 (aa 43–62), 2.5 μg/μl, dissolved in 10 μg of poly(I:C) together with PBS to the amount of 100 μl] (designated as P) twice with a 1-week interval. The mice from groups PD-P, P-D-P, and P-PD were treated with intraperitoneal injection of DMXAA (dissolved in 5% NaHCO3) at the dose of 20 μg/g of body weight on days 0, 3, and 7, respectively. One week after the last vaccination, splenocytes from mice were harvested and stained for CD8 and intracellular IFN-γ and then characterized for E7-specific CD8+ T cells using intracellular IFN-γ staining followed by flow cytometry analysis. (B) Representative data of intracellular cytokine staining followed by flow cytometry analysis showing the number of E7-specific IFN-γ+CD8+ T cells in the various groups (right upper quadrant). (C) Bar graph depicting the numbers of E7-specific IFN-γ-secreting CD8+ T cells per 3 × 105 pooled splenocytes (means ± SE). Data shown are representative of two experiments performed.

Characterization of maturation status of dendritic cells

Five- to 8-week-old C57BL/6 mice (five mice per group) were injected with 1 × 105 TC-1 cells per mouse subcutaneously. On day 13 after tumor injection, each mouse was vaccinated with 10 μg of HPV-16 E7 (aa 43–62) peptide plus 10 μg of poly(I:C) in 100 μl of volume subcutaneously. Seven days later, the mice were boosted with the same dose and regimen. At the time of booster, the experimental group of mice was given 20 mg/kg DMXAA intraperitoneally, and the control group was given the same volume of vehicle (5% NaHCO3). Twenty-four hours later, the tumor-draining lymph nodes were harvested from treated mice and single-cell preparation was prepared. The cells were then stained with anti-mouse CD45-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC), anti-mouse CD11c-APC, plus one of the following PE-conjugated antibodies: anti-mouse intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1), CD40, CD80, and CD86. The samples were acquired using a FACS Calibur flow cytometer and analyzed with CellQuest software. The cells were gated on CD45+ and CD11c+ population.

Characterization of cytokine and chemokine levels in the tumors of vaccinated mice

Five- to 8-week-old C57BL/6 mice (three or four mice per group) were injected with 1 × 105 TC-1 cells per mouse subcutaneously. On day 13 after tumor injection, each mouse was vaccinated with 10 μg of HPV-16 E7 (aa 43–62) peptide plus 10 μg of poly(I:C) in 100 μl of volume subcutaneously. Seven days later, the mice were boosted with the same regimen. At the time of booster, one group was given 20 mg/kg DMXAA intraperitoneally, and another group was given the same volume of vehicle (5% NaHCO3). Five hours later, the tumors were harvested, minced into small pieces, and sonicated for 30 sec in 1 ml of PBS containing protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche, Indianapolis, IN). The tumor tissue supernatant was collected by centrifugation and filtering through a syringe filter. Total protein concentration was measured with the BCA protein assay kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL). ELISA was performed to measure TNF-α, interferon-γ (IFN-γ) (ELISA kit from eBioscience, San Diego, CA), and interferon-inducible protein 10 (IP-10) (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) concentrations according to the manufacturer's protocols. All cytokine concentration was normalized to total protein concentration. The nitric oxide (NO) level was measured using the QuantiChrom Nitric Oxide assay kit from BioAssay Systems (Hayward, CA) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Vaginal model setting and treatment

C57BL/6 mice (five per group) were first given Depo-Provera by subcutaneous injection on the back and just behind the ears (3 mg/mouse). Four days after the injection, 3 × 105 TC-1/luciferase cells were implanted into the intravaginal cavity. For the tumor model setting, the reproductive organs were extracted at different time points for luminescent imaging and histological staining. Mice were administered peptide as the vaccine, or PBS as the negative control, by subcutaneous injection or intraperitoneal injection of DMXAA according to different regimens. Mice were examined by luminescence imaging at different time points.

Statistical analysis

All data, expressed as means ± SE, are representative of at least two different experiments. Comparisons between individual data points were made using Student's t test. Kaplan–Meier survival curves for tumor treatment experiments were applied; for differences between curves, p values were calculated using the log-rank test. The value of p < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Combination of HPV E7 peptide vaccination with DMXAA generates the best therapeutic effects against TC-1 tumors in a subcutaneous tumor model

To determine the antitumor effects of treatment with DMXAA combined with therapeutic HPV peptide-based vaccination, we first challenged groups of C57BL/6 mice (five per group) with TC-1 tumor cells subcutaneously. Mice were then treated with a mixture of E7 peptide (aa 43–62) and poly(I:C) subcutaneously with or without intraperitoneal DMXAA treatment at different time points as illustrated in Fig. 1A.

We first characterized the concentration of DMXAA in the tumor of TC-1 tumor-bearing mice at 6 hr following DMXAA treatment. We used the high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) technique for the quantitative determination of DMXAA in homogenates of tumor using the method as described previously (McPhail et al., 2005). We found that the concentration of DMXAA in TC-1 tumors at 6 hr following treatment was 13.53 ± 2.87 μM (see Supplementary Fig. 1; supplementary data are available online at www.liebertonline.com/hum). Mice were monitored for evidence of tumor growth by inspection and palpation. Tumor size was measured twice a week starting from day 8 after tumor challenge. As shown in Fig. 1B, tumor-bearing mice treated with the E7 peptide in combination with DMXAA at the second dose of peptide vaccination (P-PD) showed significantly lower tumor volumes over time compared with tumor-bearing mice treated with any of the other regimens. Furthermore, tumor-bearing mice treated with E7 peptide with DMXAA at the second dose of peptide vaccination (P-PD) showed significantly improved survival compared with tumor-bearing mice treated with the other regimens (Fig. 1C). Thus, our data suggest that the combined treatment using DMXAA with E7 peptide vaccination generates the best therapeutic antitumor effects and long-term survival in TC-1 tumor-bearing mice. Furthermore, the timing of the treatment with DMXAA plays an important role in the enhancement of antitumor effects generated by HPV peptide-based vaccine.

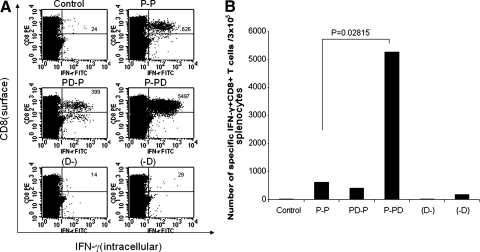

Combination of E7 peptide vaccination with DMXAA treatment generates the strongest E7-specific CD8+ T-cell immune responses in tumor-bearing mice

To determine the E7-specific CD8+ T-cell immune responses in TC-1 tumor-bearing mice treated with E7 peptide vaccination with or without DMXAA, we first challenged groups of C57BL/6 mice (five per group) with TC-1 tumor cells subcutaneously and then treated them with a mixture of E7 peptide (aa 43–62) and poly(I:C) with or without DMXAA at different time points as illustrated in Fig. 1A. Seven days after the last treatment, splenocytes from vaccinated mice were harvested and characterized for E7-specific CD8+ T-cell immune responses using intracellular cytokine staining for IFN-γ followed by flow cytometry analysis. As shown in Fig. 2, tumor-bearing mice that were administered E7 peptide vaccination in combination with DMXAA at the second dose of peptide vaccination (P-PD) generated a significantly higher number of E7-specific CD8+ T-cells compared with tumor-bearing mice that were administered any of the other regimens. In comparison, treatment with DMXAA alone did not significantly increase the number of E7-specific CD8+ T cells in tumor-bearing mice compared with untreated mice. Furthermore, we did not find any significant difference in the frequency of E7-specific CD4+ T cells in the treated mice (data not shown). Thus, our results suggest that treatment of tumor-bearing mice with DMXAA enhances the systemic E7-specific CD8+ T-cell immune responses generated by E7 peptide vaccination.

FIG. 2.

Intracellular cytokine staining followed by flow cytometry analysis to determine the number of E7-specific CD8+ T cells in tumor-bearing mice treated with the E7 peptide vaccine with or without DMXAA. Groups of C57BL/6 mice (five per group) were challenged with TC-1 tumor cells and treated with the E7 peptide vaccine with or without DMXAA using the regimen as illustrated in Fig. 1A. One week after the last vaccination, splenocytes from tumor-bearing mice were harvested and characterized for E7-specific CD8+ T cells using intracellular IFN-γ staining followed by flow cytometry analysis. (A) Representative data of intracellular cytokine staining followed by flow cytometry analysis showing the number of E7-specific IFN-γ+CD8+ T cells in the various groups (right upper quadrant). (B) Bar graph depicting the numbers of E7-specific IFN-γ-secreting CD8+ T cells per 3 × 105 pooled splenocytes (means ± SE). Data shown are representative of two experiments performed.

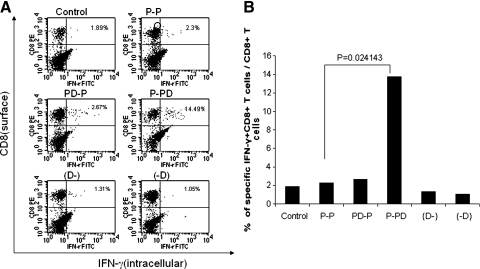

We further determined the E7-specific CD8+ T-cell immune response in the tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) of TC-1 tumor-bearing mice. As shown in Fig. 3, tumor-bearing mice that were administered E7 peptide in combination with DMXAA at the second dose of peptide vaccination (P-PD) generated a significantly higher percentage of E7-specific CD8+ T-cells in the TILs compared with tumor-bearing mice that were treated with the other regimens. Thus, our results suggest that treatment of tumor-bearing mice with DMXAA enhances the local E7-specific CD8+ T-cell immune responses in the tumors generated by E7 peptide vaccination. Furthermore, the timing of the treatment with DMXAA plays an important role in the enhancement of E7-specific CD8+ T-cell immune responses generated by HPV peptide-based vaccine.

FIG. 3.

Intracellular cytokine staining followed by flow cytometry analysis to determine the number of E7-specific CD8+ T cells in the TILs of tumor-bearing mice treated with the E7 peptide vaccine with or without DMXAA. Groups of C57BL/6 mice (five per group) were challenged with TC-1 tumor cells and treated with the E7 peptide vaccine with or without DMXAA using the regimen as illustrated in Fig. 1A. One week after the last vaccination, TILs from tumor-bearing mice were harvested and characterized for E7-specific CD8+ T cells using intracellular IFN-γ staining followed by flow cytometry analysis. (A) Representative data of intracellular cytokine staining followed by flow cytometry analysis showing the number of E7-specific IFN-γ+ CD8+ T cells in the various groups (right upper quadrant). (B) Bar graph depicting the numbers of E7-specific IFN-γ-secreting CD8+ T cells among the CD8+ T cells in the TILs (means ± SE). Data shown are representative of two experiments performed.

Treatment with DMXAA enhances the E7-specific CD8+ T-cell immune responses generated by E7 peptide vaccination in naive mice

To determine whether the E7-specific CD8+ T-cell immune responses in naive mice vaccinated with E7 peptide vaccine can be enhanced by treatment with DMXAA, we treated C57BL/6 mice (five per group) with E7 peptide vaccination with or without DMXAA at different time points as illustrated in Fig. 4A. One week after the last vaccination, splenocytes from vaccinated mice were harvested and characterized for the presence of E7-specific CD8+ T cells using intracellular cytokine staining for IFN-γ followed by flow cytometry analysis. As shown in Fig. 4B and C, treatment of naive mice with DMXAA at the second dose of peptide vaccination (P-PD) significantly enhances the E7-specific CD8+ T-cell responses generated by E7 peptide vaccination compared with treatment with DMXAA with the first peptide vaccination or between the two vaccinations. We also characterized the E7-specific CD4+ T-cell immune responses in naive mice vaccinated with E7 peptide vaccine in combination with DMXAA treatment. However, we observed only background levels of E7-specific CD4+ T cells in the treated mice (data not shown). Thus, our results suggest that treatment of naive mice with DMXAA leads to enhanced E7-specific CD8+ T-cell immune responses generated by E7 peptide vaccination when administered with the second dose of peptide vaccination.

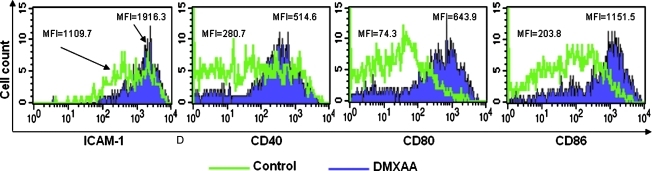

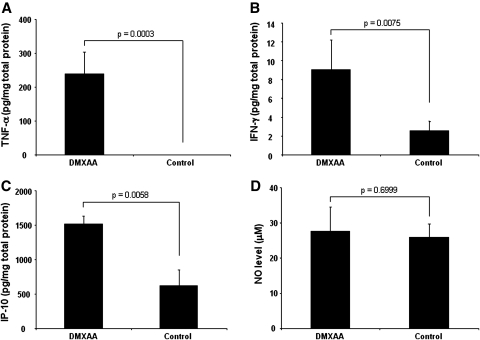

Treatment with DMXAA in tumor-bearing mice leads to increased dendritic cell maturation and increased production of inflammatory cytokines in the tumor

To determine the potential mechanisms for the observed enhancement of antigen-specific CD8+ T-cell immune responses and antitumor effects in tumor-bearing mice treated with or without DMXAA, C57BL/6 mice were injected with 1 × 105 TC-1 tumor cells subcutaneously. On day 13 after tumor injection, the mice were vaccinated with E7 peptide with poly(I:C) subcutaneously twice with a 1-week interval. Mice were then treated with or without DMXAA. One week later, the mice were boosted with the same regimen. Twenty-four hours later, the tumor-draining lymph nodes were harvested and cells were characterized by flow cytometry for the expression of dendritic cell maturation markers. As shown in Fig. 5, we found that DMXAA treatment led to increased maturation of dendritic cells in the tumor-draining lymph nodes of the treated mice. Furthermore, we characterized the levels of TNF-α, IFN-γ, IP-10, and NO by ELISA analysis in the tumor of vaccinated mice with or without DMXAA treatment. As shown in Fig. 6, we found that DMXAA treatment led to a significant increase in TNF-α, IFN-γ, and IP-10 levels in the tumors of vaccinated mice compared with mice without DMXAA treatment, whereas there was no difference in the NO levels. Thus, our data suggest that treatment with DMXAA in tumor-bearing mice leads to increased dendritic cell maturation and increased production of inflammatory cytokines in the tumor.

FIG. 5.

Characterization of the effect of DMXAA on the maturation of dendritic cells in the tumor-draining lymph nodes. Five- to 8-week-old C57BL/6 mice (five mice per group) were injected with 1 × 105 TC-1 cells subcutaneously. On day 13 after tumor injection, the mice were vaccinated with 10 μg of HPV-16 E7 (aa 43–62) peptide plus 10 μg of poly(I:C) in 100 μl of volume subcutaneously. Seven days later, the mice were boosted with the same dose and regimen. At the same time, mice were treated with 20 mg/kg DMXAA or the same volume of vehicle (5% NaHCO3) intraperitoneally. Twenty-four hours later, the tumor-draining lymph nodes were harvested from treated mice, and cells were stained with anti-mouse CD45-FITC, anti-mouse CD11c-APC, plus one of the following PE-conjugated antibodies: anti-mouse ICAM-1, CD40, CD80, and CD86. Representative flow cytometry data indicate the expression levels and the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of ICAM-1, CD40, CD80, and CD86 in tumor cells from vaccinated mice treated with or without DMXAA. Color images available online at www.liebertonline.com/hum.

FIG. 6.

Characterization of the effect of DMXAA on cytokine and chemokine levels in the tumors of vaccinated mice. Five- to 8-week-old C57BL/6 mice were injected with 1 × 105 TC-1 cells subcutaneously. On day 13 after tumor injection, the mice were vaccinated with 10 μg of HPV-16 E7 (aa 43–62) peptide plus 10 μg of poly(I:C) in 100 μl of volume subcutaneously. Seven days later, the mice were boosted with the same regimen. At the same time, mice were treated with 20 mg/kg DMXAA or the same volume of vehicle (5% NaHCO3) intraperitoneally. Five hours later, the tumors were harvested and characterized by ELISA analysis for the levels of TNF-α, IFN-γ, IP-10, and NO in the tumor cells. Representative bar graphs indicate the levels of TNF-α (A), IFN-γ (B), IP-10 (C), and NO (D) in the tumor cells from vaccinated mice treated with or without DMXAA.

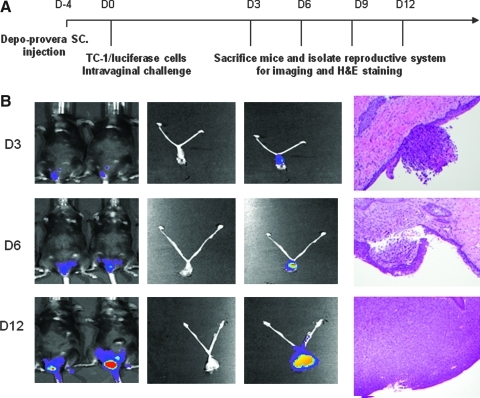

Intravaginal challenge of TC-1 tumors leads to implantation of the tumor in the epithelium of the cervicovaginal tract and results in invasive tumor

We then determined the antitumor effects of treatment with DMXAA combined with vaccination with the E7 peptide with poly(I:C) using a cervicovaginal tumor model. We have developed a novel aggressive cervicovaginal TC-1 tumor where the HPV-16 E6/E7-expressing, luciferase-expressing TC-1 tumor cells (TC-1/luciferase) are established in the cervicovaginal tract of mice and the tumor load can be measured using luminescence imaging. Figure 7A depicts the schematic diagram of the preparation of the mice for TC-1/luciferase tumor challenge and the schedule for imaging and histological examination. As shown in Fig. 7B, on day 3, the tumor implant was observed within the epithelium of the cervicovaginal tract. The tumor began to invade the underlying stroma on day 6 and formed a significant tumor mass on day 12. We also observed that the luminescence intensity correlates well with the tumor load in the cervicovaginal tract. Thus, this orthotopic implanted TC-1 tumor model recapitulates many aspects of cervical cancer tumor progression in the cervicovaginal tract.

FIG. 7.

Development of the cervicovaginal model. C57BL/6 mice were inoculated with luciferase-expressing TC-1 tumor cells intravaginally. The tumor growth was monitored by luminescence imaging using the IVIS 200 system. Four days before TC-1 tumor challenge, mice were treated with Depo-Provera, a contraceptive drug, via subcutaneous injection. The mice were sacrificed on days 3, 6, 9, and 12 following tumor challenge, and their reproductive systems were extracted and imaged. (A) Schematic diagram of the imaging of the cervicovaginal tumor model. (B) First column: representative luminescence images of tumor-bearing mice to demonstrate the tumor load in the cervicovaginal tract; second column: images of the extracted reproductive systems from tumor-bearing mice; third column: luminescence images of the extracted reproductive systems from tumor-bearing mice; and fourth column: representative histological figures depicting TC-1 tumor growth in the cervicovaginal tract over time.

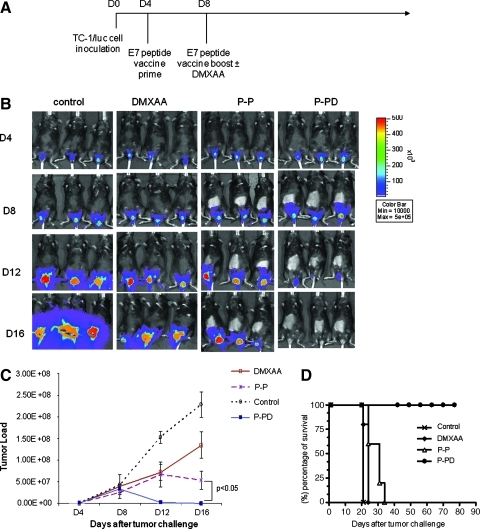

Combination of E7 peptide vaccination with DMXAA treatment generates the best therapeutic effects against TC-1 tumors in tumor-bearing mice using a cervicovaginal tumor model

To explore if the combination of therapeutic HPV peptide vaccination with DMXAA can lead to the control of TC-1 tumors implanted in the cervicovaginal tract, we challenged C57BL/6 mice (five per group) with TC-1/luciferase cells intravaginally and then treated them with the mixture of E7 peptide (aa 43–62) and poly(I:C) with or without DMXAA at different time points as illustrated in Fig. 8A. Mice were monitored for evidence of tumor growth by luminescence imaging using the IVIS 200 system. As shown in Fig. 8B and C, tumor-bearing mice treated with the E7 peptide in combination with DMXAA at the second dose of peptide vaccination (P-PD) showed significantly lower tumor volumes over time, as demonstrated by the significant reduction in luminescence intensity compared with tumor-bearing mice treated with the other regimens. Furthermore, tumor-bearing mice treated with E7 peptide with DMXAA at the second dose of peptide vaccination (P-PD) showed significantly improved survival compared with tumor-bearing mice treated with any of the other regimens (p < 0.001) (Fig. 8D). Thus, our data suggest that the combined treatment using DMXAA with E7 peptide vaccination generates the best therapeutic antitumor effects and long-term survival in TC-1 tumor-bearing mice.

FIG. 8.

In vivo tumor treatment experiments using the cervicovaginal model. (A) Schematic diagram of the treatment regimen of E7 peptide vaccine and/or DMXAA. Groups of C57BL/6 mice (five per group) were challenged with 3 × 105 TC-1/luciferase cells intravaginally on day 0. Four days later, mice were administered E7 long peptide vaccine or PBS as the negative control by subcutaneous injection. Mice were boosted with the vaccine and treated with or without intraperitoneal injection of DMXAA on day 8. Mice were monitored for evidence of tumor growth by luminescence imaging using the IVIS 200 system. (B) Luminescence images of representative mice intravaginally challenged with TC-1/luciferase cells and treated with E7 peptide vaccine with or without DMXAA. (C) Line graph depicting the tumor volume in TC-1 tumor-bearing mice treated with E7 peptide vaccine with or without DMXAA (means ± SE) (p < 0.05). (D) Kaplan–Meier survival analysis of TC-1 tumor-bearing mice treated with E7 peptide vaccine with or without DMXAA (p < 0.001). Data shown are representative of two experiments performed. Color images available online at www.liebertonline.com/hum.

Discussion

In the current study, we tested the combination of E7 long peptide vaccination with DMXAA treatment for their ability to generate E7-specific CD8+ T-cell immune responses as well as antitumor effects in treated mice. We found that the coadministration of DMXAA with E7 peptide vaccination significantly enhanced E7-specific CD8+ T-cell immune responses as well as therapeutic antitumor effects against TC-1 tumors in a subcutaneous tumor model as well as in a cervicovaginal tumor model. Furthermore, we found that the DMXAA-mediated enhancement of E7-specific CD8+ T-cell immune responses as well as antitumor effects was dependent on the timing of administration of DMXAA. In addition, treatment with DMXAA in tumor-bearing mice was shown to lead to increased dendritic cell maturation and increased production of inflammatory cytokines in the tumor. Our observations serve as an important foundation for further exploration of this combinational therapy for the control of HPV-associated tumors in future clinical trials.

In our study, we have introduced a novel aggressive tumor model where the HPV-16 E6/E7-expressing TC-1 tumor cells are implanted in the cervicovaginal tract of mice, in addition to the conventional subcutaneous TC-1 tumor model. This orthotopic implanted TC-1 tumor model recapitulates many aspects of cervical cancer tumor progression in the cervicovaginal tract (Lyons, 2005). The tumor first gets implanted into the epithelium, which resembles carcinoma in situ (precancerous lesions) (Fig. 5B). With time, the tumor invades the underlying stroma and forms a significant tumor mass. Thus, the cervicovaginal tumor model shares a similar tumor microenvironment and bears a close resemblance to HPV-associated tumors in humans. Therefore, we believe this model may serve as a potentially more ideal preclinical model than the subcutaneous tumors to test therapeutic approaches against HPV-associated lesions.

In our study, we have used a vaccination strategy using the E7 long peptide (aa 43–62). This synthetic E7 long peptide includes the immunodominant CTL epitope (aa 49–57) (Feltkamp et al., 1993) as well as the T-helper epitope (aa 48–54) (Tindle et al., 1991) of the E7 protein. Thus, this long peptide can potentially induce HPV-16–specific CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell responses. Furthermore, previous clinical trials using HPV-16 E6 and/or E7 overlapping long peptides have shown significant E6/E7-specific CD4+ as well as CD8+ T-cell responses in patients with HPV-associated lesions (Kenter et al., 2008, 2009; Welters et al., 2008). The inclusion of CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell epitopes is most likely important for the ability of the peptide to elicit potent E7-specific CD8+ T-cell immune responses and antitumor effects against E7-expressing tumors. However, in our study, we have observed only E7-specific CD8+ T-cell immune responses (see Figs. 2 and 4), but not E7-specific CD4+ T-cell responses using this long peptide by intracellular cytokine staining followed by flow cytometry analysis (data not shown). One potential reason that may account for the lack of CD4+ T-cell immune responses in our study may be related to the assay used to characterize the E7-specific CD4+ T-cell immune responses. In the original publication by Tindle et al. (1991), the T-cell proliferation assay was used as a readout for the characterization of E7-specific CD4+ T cells. In comparison, we used intracellular cytokine staining followed by flow cytometry analysis, which is a more quantitative immunological assay for characterization of antigen-specific T cells.

Our data indicate that the timing of administration of DMXAA plays an essential role in the enhancement of antigen-specific immune responses and antitumor effects generated by E7 peptide vaccination. We observed that treatment with the E7 peptide in combination with DMXAA at the second dose of peptide vaccination (P-PD) generated the strongest immune responses and antitumor effects compared with the other treatment regimens (Figs. 1–4). This suggests that DMXAA may be involved in increasing the number of CD8+ T-cell precursors that are generated by the first peptide vaccination, thus resulting in an enhanced antigen-specific CD8+ T-cell immune response.

In our study, we have observed that treatment with DMXAA is capable of enhancing the E7-specific CD8+ T-cell immune responses generated by E7 peptide vaccination in tumor-bearing mice (Fig. 2) as well as in naive mice without tumor (Fig. 4). DMXAA has been shown to destroy the established tumor vasculature to cause tumor-cell necrosis. The released tumor antigen may subsequently be processed by dendritic cells and result in the priming of tumor antigen-specific CD8+ T cells, so-called “cross-priming.” Thus, treatment with DMXAA in tumor-bearing mice may contribute to the enhancement of tumor antigen-specific CD8+ T-cell immune responses through cross-priming mechanisms.

Another potential mechanism for the enhancement of E7-specific CD8+ T-cell immune responses mediated by DMXAA in E7 peptide-vaccinated mice may be related to the direct activation of dendritic cells by DMXAA (see Fig. 5). It has been shown that DMXAA directly activates dendritic cells through a MyD88-independent mechanism, thus leading to the activation of tumor-specific CD8+ T cells (Wallace et al., 2007). Thus, it is quite likely that the activation of dendritic cells generated by treatment with DMXAA may contribute to the enhancement of E7-specific CD8+ T-cell immune responses in E7 peptide-vaccinated mice.

For eventual clinical translation, it is essential to determine the safety profile of the drugs used and to address any safety concerns that may arise. In this respect, our current treatment approach appears to be highly translatable. The E7 long peptide vaccine has been tested in several clinical trials and has proven to be safe (Kenter et al., 2008, 2009; Welters et al., 2008). DMXAA has demonstrated a good safety profile and has been shown to be promising in phase I clinical trials (McKeage et al., 2006). Poly(I:C) has also been used in clinical trials and shown to have minimal toxicity (Thompson et al., 1996). Thus, all the reagents used in our study have proven to be clinically safe.

In summary, our study demonstrated that the combination of E7 peptide vaccination with DMXAA treatment generates potent E7-specific CD8+ T-cell immune responses, resulting in significant therapeutic effects against E7-expressing tumors in two different locations. It would be important to further determine the optimal dose and regimen of DMXAA and E7 long peptide vaccine treatment in order to generate the best therapeutic effects in a preclinical model. Furthermore, DMXAA and peptide vaccination lead to enhanced antitumor effects through different mechanisms compared with other therapeutic interventions, such as chemotherapy and radiation. The combination of DMXAA with peptide-based vaccination does not lead to the direct killing of tumor cells, but instead acts mainly on vascular disruption and tumor antigen-specific immune responses. In comparison, chemotherapy and radiation mainly lead to direct killing of tumor cells. This creates the opportunity to combine DMXAA with these interventions as well as immunotherapy for further enhancement of the therapeutic antitumor effects.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge Ms. Barbara Ma for assistance in preparation and critical review of the manuscript. This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute SPORE in Cervical Cancer P50 CA098252, 1 RO1 CA114425-01, P20 CA118770, and 1 RO1 CA140746-01.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- Baguley B.C. Antivascular therapy of cancer: DMXAA. Lancet Oncol. 2003;4:141–148. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(03)01018-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosch F.X. Lorincz A. Munoz N., et al. The causal relation between human papillomavirus and cervical cancer. J. Clin. Pathol. 2002;55:244–265. doi: 10.1136/jcp.55.4.244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai S.X. Small molecule vascular disrupting agents: potential new drugs for cancer treatment. Recent Pat. Anticancer Drug Discov. 2007;2:79–101. doi: 10.2174/157489207779561462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui Z. Qiu F. Synthetic double-stranded RNA poly(I:C) as a potent peptide vaccine adjuvant: therapeutic activity against human cervical cancer in a rodent model. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2006;55:1267–1279. doi: 10.1007/s00262-005-0114-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feltkamp M.C. Smits H.L. Vierboom M.P., et al. Vaccination with cytotoxic T lymphocyte epitope-containing peptide protects against a tumor induced by human papillomavirus type 16-transformed cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 1993;23:2242–2249. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830230929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garland S.M. Hernandez-Avila M. Wheeler C.M., et al. Quadrivalent vaccine against human papillomavirus to prevent anogenital diseases. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007;356:1928–1943. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper D.M. Currently approved prophylactic HPV vaccines. Expert Rev. Vaccines. 2009;8:1663–1679. doi: 10.1586/erv.09.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper D.M. Franco E.L. Wheeler C., et al. Efficacy of a bivalent L1 virus-like particle vaccine in prevention of infection with human papillomavirus types 16 and 18 in young women: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;364:1757–1765. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17398-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper D.M. Franco E.L. Wheeler C.M., et al. Sustained efficacy up to 4.5 years of a bivalent L1 virus-like particle vaccine against human papillomavirus types 16 and 18: follow-up from a randomised control trial. Lancet. 2006;367:1247–1255. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68439-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Head M. Jameson M.B. The development of the tumor vascular-disrupting agent ASA404 (vadimezan, DMXAA): current status and future opportunities. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs. 2010;19:295–304. doi: 10.1517/13543780903540214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hildesheim A. Herrero R. Wacholder S., et al. Effect of human papillomavirus 16/18 L1 viruslike particle vaccine among young women with preexisting infection: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2007;298:743–753. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.7.743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang B. Mao C.P. Peng S., et al. Intradermal administration of DNA vaccines combining a strategy to bypass antigen processing with a strategy to prolong dendritic cell survival enhances DNA vaccine potency. Vaccine. 2007;25:7824–7831. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.08.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hung C.F. Cheng W.F. Chai C.Y., et al. Improving vaccine potency through intercellular spreading and enhanced MHC class I presentation of antigen. J Immunol. 2001;166:5733–5740. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.9.5733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hung C.F. Ma B. Monie A., et al. Therapeutic human papillomavirus vaccines: current clinical trials and future directions. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 2008;8:421–439. doi: 10.1517/14712598.8.4.421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenter G.G. Welters M.J. Valentijn A.R., et al. Phase I immunotherapeutic trial with long peptides spanning the E6 and E7 sequences of high-risk human papillomavirus 16 in end-stage cervical cancer patients shows low toxicity and robust immunogenicity. Clin. Cancer Res. 2008;14:169–177. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenter G.G. Welters M.J. Valentijn A.R., et al. Vaccination against HPV-16 oncoproteins for vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009;361:1838–1847. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J.W. Hung C.F. Juang J., et al. Comparison of HPV DNA vaccines employing intracellular targeting strategies. Gene Ther. 2004;11:1011–1018. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin K.Y. Guarnieri F.G. Staveley-O'Carroll, et al. Treatment of established tumors with a novel vaccine that enhances major histocompatibility class II presentation of tumor antigen. Cancer Res. 1996;56:21–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons S.K. Advances in imaging mouse tumour models in vivo. J. Pathol. 2005;205:194–205. doi: 10.1002/path.1697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKeage M.J. Fong P. Jeffery M., et al. 5,6-Dimethylxanthenone-4-acetic acid in the treatment of refractory tumors: a phase I safety study of a vascular disrupting agent. Clin. Cancer Res. 2006;12:1776–1784. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKeage M.J. Reck M. Jameson M.B., et al. Phase II study of ASA404 (vadimezan, 5,6-dimethylxanthenone-4-acetic acid/DMXAA) 1800 mg/m2 combined with carboplatin and paclitaxel in previously untreated advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2009;65:192–197. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2009.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPhail L.D. Chung Y.L. Madhu B., et al. Tumor dose response to the vascular disrupting agent, 5,6-dimethylxanthenone-4-acetic acid, using in vivo magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Clin. Cancer Res. 2005;11:3705–3713. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melief C.J. van der Burg S.H. Immunotherapy of established (pre)malignant disease by synthetic long peptide vaccines. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2008;8:351–360. doi: 10.1038/nrc2373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paavonen J. Naud P. Salmeron J., et al. Efficacy of human papillomavirus (HPV)-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine against cervical infection and precancer caused by oncogenic HPV types (PATRICIA): final analysis of a double-blind, randomised study in young women. Lancet. 2009;374:301–314. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61248-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkin D.M. Bray F. Ferlay J. Pisani P. Global cancer statistics, 2002. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2005;55:74–108. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.55.2.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roden R. Wu T.C. Preventative and therapeutic vaccines for cervical cancer. Expert Rev. Vaccines. 2003;2:495–516. doi: 10.1586/14760584.2.4.495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stahl-Hennig C. Eisenblätter M. Jasny E., et al. Synthetic double-stranded RNAs are adjuvants for the induction of T helper 1 and humoral immune responses to human papillomavirus in rhesus macaques. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000373. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson K.A. Strayer D.R. Salvato P.D., et al. Results of a double-blind placebo-controlled study of the double-stranded RNA drug polyI:polyC12U in the treatment of HIV infection. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 1996;15:580–587. doi: 10.1007/BF01709367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tindle R.W. Fernando G.J. Sterling J.C. Frazer I.H. A “public” T-helper epitope of the E7 transforming protein of human papillomavirus 16 provides cognate help for several E7 B-cell epitopes from cervical cancer-associated human papillomavirus genotypes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1991;88:5887–5891. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.13.5887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Cancer Statistics Working Group. (United States Cancer Statistics: 1999–2006) Incidence and Mortality Web-based Report. Atlanta, GA: Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and National Cancer Institute; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Vambutas A. DeVoti J. Nouri M., et al. Therapeutic vaccination with papillomavirus E6 and E7 long peptides results in the control of both established virus-induced lesions and latently infected sites in a pre-clinical cottontail rabbit papillomavirus model. Vaccine. 2005;23:5271–5280. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.04.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walboomers J.M. Jacobs M.V. Manos M.M., et al. Human papillomavirus is a necessary cause of invasive cervical cancer worldwide. J. Pathol. 1999;189:12–19. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199909)189:1<12::AID-PATH431>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace A. LaRosa D.F. Kapoor V., et al. The vascular disrupting agent, DMXAA, directly activates dendritic cells through a MyD88-independent mechanism and generates antitumor cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Cancer Res. 2007;67:7011–7019. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L.C. Ching L.M. Paxton J.W., et al. Enhancement of the action of the antivascular drug 5,6-dimethylxanthenone-4-acetic acid (DMXAA; ASA404) by non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Invest. New Drugs. 2009;27:280–284. doi: 10.1007/s10637-008-9167-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welters M.J. Kenter G.G. Piersma S.J., et al. Induction of tumor-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell immunity in cervical cancer patients by a human papillomavirus type 16 E6 and E7 long peptides vaccine. Clin. Cancer Res. 2008;14:178–187. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwaveling S. Ferreira Mota S.C. Nouta J., et al. Established human papillomavirus type 16-expressing tumors are effectively eradicated following vaccination with long peptides. J. Immunol. 2002;169:350–358. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.1.350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.