Abstract

Small Heterodimer Partner (SHP) inhibits numerous transcription factors that are involved in diverse biological processes, including lipid and glucose metabolism. In response to increased hepatic bile acids, SHP gene expression is induced and the SHP protein is stabilized. We now show that the activity of SHP is also increased by posttranslational methylation at Arg-57 by protein arginine methyltransferase 5 (PRMT5). Adenovirus-mediated hepatic depletion of PRMT5 decreased SHP methylation and reversed the suppression of metabolic genes by SHP. Mutation of Arg-57 decreased SHP interaction with its known cofactors, Brm, mSin3A, and histone deacetylase 1 (HDAC1), but not with G9a, and decreased their recruitment to SHP target genes in mice. Hepatic overexpression of SHP inhibited metabolic target genes, decreased bile acid and hepatic triglyceride levels, and increased glucose tolerance. In contrast, mutation of Arg-57 selectively reversed the inhibition of SHP target genes and metabolic outcomes. The importance of Arg-57 methylation for the repression activity of SHP provides a molecular basis for the observation that a natural mutation of Arg-57 in humans is associated with the metabolic syndrome. Targeting posttranslational modifications of SHP may be an effective therapeutic strategy by controlling selected groups of genes to treat SHP-related human diseases, such as metabolic syndrome, cancer, and infertility.

INTRODUCTION

Small Heterodimer Partner (SHP) (NR0B2) was discovered as a unique member of the nuclear receptor superfamily that lacks a DNA binding domain but contains a putative ligand binding domain (32). SHP forms nonfunctional heterodimers with DNA binding transcriptional factors, including nuclear receptors, and thereby acts as a transcriptional corepressor in diverse biological processes, including metabolism, cell proliferation, apoptosis, and sexual maturation (1, 3, 11, 35, 36, 39). Well-studied hepatic functions of SHP are the inhibition of bile acid biosynthesis, fatty acid synthesis, and glucose production in response to bile acid signaling (1, 3, 4, 12, 19, 22, 37, 38). We previously showed that SHP inhibits the expression of a key bile acid biosynthetic gene, the CYP7A1 (cholesterol 7α hydroxylase) gene, by coordinately recruiting chromatin-modifying repressive cofactors, mSin3A/histone deacetylase 1 (HDAC1), NCoR/HDAC3, methyltransferase G9a, and the Swi/Snf-Brm remodeling complex, to the CYP7A1 gene promoter (9, 16, 25). GPS2, a subunit of the NCoR corepressor complex, was recently shown to act as a SHP cofactor and participates in differential regulation of bile acid biosynthetic genes, the CYP7A1 and CYP8B1 (sterol 12α hydroxylase) genes (31).

Consistent with its important functions in metabolic pathways, naturally occurring heterozygous mutations in the SHP gene have been associated with human metabolic disorders (7, 8, 27). About 30% of these reported mutations occur at arginine residues, implying that functionally relevant posttranslational modification (PTM) at these sites may be important for SHP function. In response to elevated hepatic bile acid levels, SHP gene induction by the nuclear bile acid receptor Farnesoid X receptor (FXR) has been established (12, 22). We recently found that SHP undergoes rapid degradation in hepatocytes and that SHP stability is increased by bile acid-activated extracellular signal-related kinase (ERK)-mediated phosphorylation, which inhibits its ubiquitination (26). In addition to these changes in the levels of SHP, it is possible that the repression activity of SHP is also regulated in response to elevated hepatic bile acid levels.

Protein arginine methyltransferases (PRMTs) are enzymes that catalyze the transfer of methyl groups from S-adenosyl methionine (SAM) to the guanidino nitrogen of Arg (2, 21). Type I or type II PRMTs catalyze asymmetric or symmetric dimethylation of Arg, respectively. Both types of PRMTs also catalyze monomethylation of Arg. PRMT5 is a type II enzyme that methylates nonhistone proteins, as well as histones (2, 21). PRMT5 acts as a transcriptional repressor by methylating histones H3 and H4 and transcriptional elongation factor SPT5 (20, 28). Recent studies have shown that PRMT5 plays an essential role in Brg1-dependent chromatin remodeling and gene activation during myogenesis (6) and that PRMT5 is required for early gene expression in the temporal control of myogenesis (5). Arg methylation of Piwi proteins also plays an important role in the small noncoding piwi-interacting RNA (piRNA) pathway in germ cells (34). PRMT5 was recently shown to regulate the function of p53 in response to DNA damage by catalyzing Arg methylation (15). However, the functional roles of PRMT5 as an important transcriptional coregulator of metabolic pathways have not been reported.

Using molecular, cellular, and in vivo mouse studies, we demonstrate that posttranslational methylation by PRMT5 enhances SHP activity in response to bile acid signaling. PRMT5 methylated SHP at Arg-57, which is the site of a naturally occurring mutation associated with the metabolic syndrome in humans (7, 8, 27).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials and reagents.

Antibodies for SHP (sc30169), lamin A (sc-20680), tubulin (sc-8035), HDAC1 (sc-7872), mSin3A (sc-994), Brm (sc6450), liver receptor homologue 1 (LRH-1) (sc-5995 X), PolII (sc-9001), and green fluorescent protein (GFP) (sc-8334) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology; M2 antibody was from Sigma; and antibodies for PRMT5, G9a, and dimethyl symmetric Arg (SYM10) were purchased from Upstate Biotechnology. Purified recombinant PRMT5 protein was purchased from Abnova.

Construction of plasmids and adenoviral vectors.

The expression plasmids, pcDNA3 Flag-R57W, and R57K mutants were generated using a QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene), and positive clones were identified by DNA sequencing. For constructing adenovirus (Ad)-Flag-human SHP wild-type (WT) and R57W mutant adenoviral vectors, the 0.9-kb fragment from pCDNA3-flagSHP was inserted into the Ad-Track-cytomegalovirus (CMV) vector digested with XbaI. For Ad-siPRMT5 construction, small interfering RNA (siRNA) sequences for PRMT5 were used as described previously (29). Annealed siRNA oligonucleotides were inserted into the BamHI/HindIII sites of the pRNATin-H1.2/Hygro vector. A 4.5-kb fragment with the H1 promoter and siRNA oligonucleotides was cut from pRNATin-siPRMT5 and inserted into the BglII/HindIII sites of the Ad-Track vector.

Cell culture and transfection reporter assay.

HepG2 cells (ATCC HB8065) were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM)/F12 (1:1). Cos-1 cells were maintained in DMEM. The cells were transfected with plasmids or infected with adenoviral vectors, incubated with serum-free medium overnight, and treated with 50 μM chenodeoxycholic acid (CDCA) for the times indicated in the figure legends.

In vivo experiments.

Male BALB/c mice were injected in the tail vein with Ad-Flag-SHP, control Ad-empty, Ad-siPRMT5, or control scrambled RNA (0.5 × 109 to 1.0 × 109 active viral particles in 200 μl phosphate-buffered saline [PBS]). Five to 7 days after infection, the mice were fed normal or 0.5% cholic acid (CA)-supplemented chow for 3 h starting at 5 p.m., and tissues were collected at 8 p.m. for further analysis. Feeding mice with CA chow for 3 h increased Shp mRNA levels and decreased Cyp7a1 mRNA levels (25). For in vivo methylation assays, Flag-SHP was immunoprecipitated under stringent conditions with SDS-containing RIPA buffer, and methylated SHP at Arg was detected by Western analysis using SYM10 antibody. All animal use and adenoviral protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use and Institutional Biosafety Committees at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and were in accordance with National Institutes of Health guidelines.

Measurement of bile acid pool and liver triglyceride levels.

The bile acid pool from the gallbladder, liver, and small intestine was measured by colorimetric analysis (Trinity Biotechnology). Liver triglyceride levels were measured using Sigma kit TR0100 according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Glucose and insulin tolerance test.

Male BALB/c mice were injected in the tail vein with control Ad-empty, Ad-Flag-SHP WT, or R57W (0.5 × 109 to 1.0 × 109 active viral particles in 200 μl PBS). Seven days after infection, the mice were fasted for 6 h and intraperitoneally (i.p.) injected with glucose solution (Sigma, Inc.; 2 g/kg of body weight) or insulin (Sigma, Inc.; 2 units/kg), and glucose levels were measured using an Accu-chek Aviva glucometer (Roche, Inc.).

qRT-PCR.

Total RNA was isolated using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen), cDNA was synthesized using a reverse transcriptase kit (Promega), and quantitative reverse transcription (qRT)-PCR was performed with an iCycler iQ (Bio-Rad). The amount of mRNA for each gene was normalized to that of 36B4 mRNA. Primer sequences are available on request.

Mass spectrometry analyses.

Flag-human SHP was expressed in HepG2 cells (three 15-cm plates per group) by adenovirus infection, and 48 h later, the cells were treated with 5 μM MG132 for 4 h to inhibit degradation and then further treated with CDCA for 1 h. Flag-SHP was isolated in RIPA (SDS) lysis buffer using M2 agarose and then incubated with purified PRMT5 (purchased from Abnova) and unlabeled SAM at 30°C for 1 h. Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and visualized by colloidal staining, and Flag-SHP bands were excised and subjected to liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC–MS-MS) analysis. To identify SHP-interacting proteins in vivo, mice were infected with Ad-Flag-human SHP; 5 days later, the mice were fed normal chow or CA chow for 3 h, and liver extracts were prepared. The Flag-SHP complex was isolated in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM EDTA, and 0.1% NP-40) using M2 agarose, and interacting proteins were identified using LC–MS-MS.

In vitro and in-cell methylation assays.

HepG2 cells (one 15-cm plate/group) infected with Ad-Flag-SHP were treated with MG132 for 4 h and further treated with CDCA or vehicle for 1 h. Flag-SHP was isolated using M2 agarose and then incubated with purified PRMT5 and radioactively labeled or unlabeled SAM in methylation buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 2 mM EDTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol [DTT]) at 30°C for 1 h as previously described (9). Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE, and methylated SHP was detected by autoradiography or Western analysis. For in vitro assays, glutathione S-transferase (GST)-SHP was incubated with purified PRMT5 and SAM in methylation buffer at 30°C for 1 h.

GST pulldown and CoIP assays.

Standard GST pulldown assays and coimmunoprecipitation (CoIP) were performed as described previously (9, 10, 25). Briefly, for CoIP assays, cells were transfected with expression plasmids or infected with adenoviral vectors and treated with vehicle or CDCA for 1 to 3 h. Cell extracts were prepared in CoIP buffer (50 mM Tris, pH. 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 0.3% NP-40, 10% glycerol) supplemented with protease inhibitors, DTT, and phosphatase inhibitors (Na orthovanadate, sodium fluoride, sodium orthophosphate, and sodium molybdate). The cell pellets were briefly sonicated and centrifuged. The supernatant was incubated with 1 to 2 μg antibodies for 30 min, and 30 μl of 25% protein G agarose was added. Two hours later, samples were washed with the CoIP buffer 3 times, and the proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and detected by Western analysis.

In vivo ChIP and re-ChIP assays.

Chromatin IP (ChIP) assays in mouse liver were carried out essentially as described previously (9, 10, 18, 24, 25). Re-ChIP assays were performed as described previously (10). Briefly, chromatin precipitated by M2 antibody was extensively washed, eluted by adding 50 μl of 10 mM DTT at 37°C for 30 min, diluted (20-fold) with buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100), and reprecipitated using antibodies to SHP and its interacting proteins. The occupancy of proteins at the target gene promoters was examined using semiquantitative PCR. Primer sequences are available on request.

RESULTS

PRMT5 interacts with SHP in response to bile acid signaling.

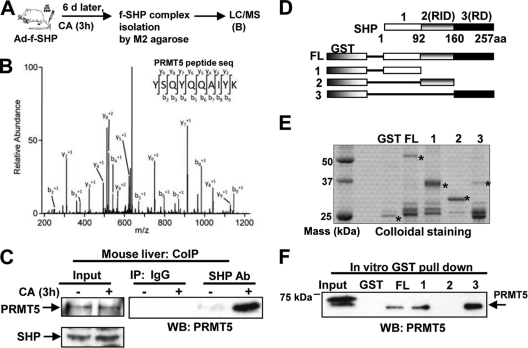

The association of mutations in Arg residues of SHP with the metabolic syndrome in humans (7, 8, 27) led us to examine whether PTMs at Arg might be important for regulating SHP activity. To identify enzymes that catalyze PTMs and interact with SHP, human Flag-SHP was expressed in mouse liver by infection with an adenoviral expression vector, Flag-SHP was affinity purified, and associated proteins were identified by mass spectrometric analysis (Fig. 1 A). PRMT5 was associated with SHP in mice fed a primary bile acid-CA diet (Fig. 1B). To confirm this result, endogenous SHP was immunoprecipitated from liver nuclear extracts, and PRMT5 in the anti-SHP immunoprecipitates was detected by Western analysis. Interaction of SHP with PRMT5 was dramatically increased in mice fed CA (Fig. 1C). Similar results were observed in HepG2 cells treated with a primary bile acid-CDCA (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

PRMT5 interacts with SHP after bile acid treatment. (A) Mice were injected via tail veins with adenoviral vector expressing Flag-SHP (f-SHP), and 6 days (d) later, the mice were fed 0.5% CA-supplemented chow for 3 h, and liver extracts were prepared. The Flag-SHP complex was isolated using M2 agarose, and interacting proteins were identified by LC–MS-MS. (B) Tandem-MS spectrum of a PRMT5 peptide identified in the SHP complex. seq, sequence. (C) Mice were fed normal or CA chow for 3 h, and the interaction of endogenous SHP with PRMT5 in liver extracts was examined by CoIP. Ab, antibody; WB, Western blotting. (D) Schematic diagrams of the receptor-interacting domain (RID) and intrinsic repression domain (RD) in SHP. aa, amino acids. (E) Amounts of GST or GST-SHP full-length (FL) or deletion mutants used in the reactions were visualized by staining. GST and GST-SHP proteins are indicated by asterisks. (F) Interaction of PRMT5 with GST-SHP proteins was detected by Western analysis using PRMT5 antibody.

To test whether PRMT5 directly interacts with SHP, in vitro GST pulldown assays were performed (Fig. 1D to F). PRMT5 directly interacted with N-terminal and C-terminal fragments, as well as full-length SHP, indicating two independent PRMT5 binding domains were present in SHP (Fig. 1F). Similar results were obtained with GST pulldown assays using 35S-labeled PRMT5 (data not shown). These results show that PRMT5 interacts with SHP in mouse liver in vivo in response to bile acid signaling.

PRMT5 augments SHP repression activity.

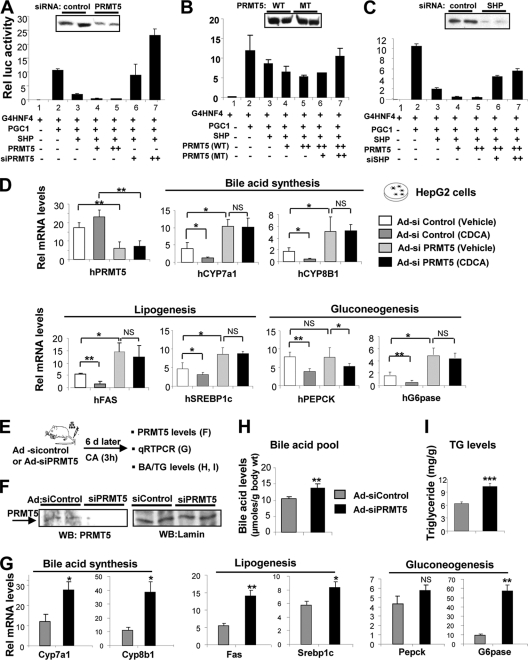

To test whether PRMT5 interaction with SHP is functionally relevant, cell-based reporter assays were performed using gain- or loss-of-function experiments. In a Gal4 reporter system, overexpression of SHP inhibited the transactivation mediated by Gal4-hepatocye nuclear factor 4 (HNF-4) (Fig. 2 A, lanes 2 and 3) and Gal4–LRH-1 (data not shown). Exogenous expression of PRMT5 augmented SHP-mediated inhibition of HNF-4/PGC-1α (Fig. 2A, lanes, 3 to 5) and LRH-1 (data not shown). Conversely, depletion of endogenous PRMT5 by siRNA or overexpression of catalytically inactive PRMT5 mutant reversed SHP inhibition of HNF-4/PGC-1α (Fig. 2A and B). Importantly, enhancement of SHP repression by PRMT5 was not observed when SHP was downregulated by siRNA (Fig. 2C). These results, together with CoIP studies (Fig. 1), suggest that PRMT5 enhances repression of HNF-4/PGC-1α and LRH-1 transactivation, probably through its interaction with SHP.

Fig. 2.

PRMT5 augments repression activity by SHP. (A to C) HepG2 cells were transfected with a Gal4-TATA-luc reporter and expression plasmids as indicated, and 36 h later, the cells were treated with CDCA overnight and reporter assays were performed. The values for firefly luciferase (luc) activities were normalized by dividing by the β-galactosidase activities. The means and standard errors of the mean (SEM) (n = 3) are plotted. Rel, relative; MT, mutant. ++ increasing amount. (D) HepG2 cells were infected with Ad-siPRMT5 or control Ad-siRNA, and then 2 days later, the cells were treated with vehicle or 50 μM CDCA overnight and the mRNA levels of bile acid synthetic, lipogenic, and gluconeogenic genes were measured by qRT-PCR. h, human. (E to I) Effects of hepatic PRMT5 depletion on expression of known SHP target genes and metabolic outcomes. (E) Experimental outline for in vivo PRMT5 depletion experiments. BA, bile acid; TG, triglyceride. (F) Endogenous PRMT5 levels were detected by Western analysis. (G) Expression of SHP target genes was examined. (H and I) Bile acid pool and hepatic triglyceride levels were measured. (G to I) The means and SEM (n = 3) are plotted. Statistical significance was determined using Student's t test. *, **, and NS indicate P values of <0.05 and <0.01 and statistically not significant, respectively.

Effects of hepatic PRMT5 depletion on expression of SHP metabolic target genes.

To determine the functional role of PRMT5 in metabolic regulation by SHP, endogenous PRMT5 in HepG2 cells was downregulated, and the expression of known SHP metabolic target genes was examined. CDCA treatment resulted in decreased mRNA levels of the bile acid biosynthetic CYP7A1 and CYP8B1 genes, lipogenic FAS and SREBP-1c genes, and the gluconeogenic glucose-6-phosphatase and PEPCK genes (Fig. 2D). Downregulation of PRMT5 reversed these effects on expression of the metabolic genes, except that of PEPCK (Fig. 2D). These results indicate that PRMT5 plays a role in the regulation of lipid and glucose metabolism by SHP.

To explore the in vivo significance of PRMT5 in metabolic regulation by SHP, endogenous PRMT5 in mouse liver was depleted by adenoviral-vector-mediated expression of siRNA, and the expression of known SHP metabolic target genes was examined (Fig. 2E). Hepatic PRMT5 protein levels were markedly decreased, whereas control lamin levels were not changed (Fig. 2F). Depletion of PRMT5 resulted in increased mRNA levels of the bile acid biosynthetic Cyp7a1 and Cyp8b1 genes, lipogenic Fas and Srebp-1c genes, and the gluconeogenic glucose-6-phosphatase gene, but not the PEPCK gene (Fig. 2G). Consistent with these results, bile acid pools from liver, gallbladder, and intestine and liver triglyceride levels were significantly increased in these mice (Fig. 2H and I). These results demonstrate that PRMT5 plays a role in the regulation of liver metabolism by SHP.

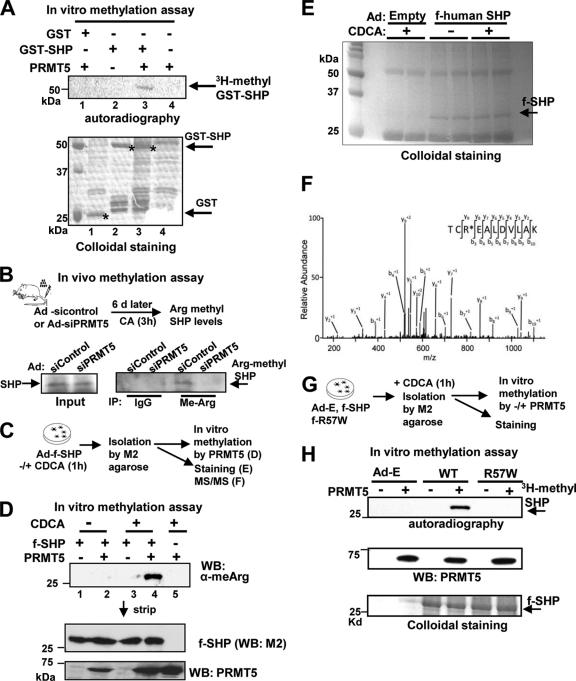

PRMT5 methylates SHP in vitro and in vivo.

To test if PRMT5 can methylate SHP, GST-SHP or control GST was incubated with purified PRMT5 and [3H]SAM in vitro. GST-SHP was methylated by PRMT5 in the presence of [3H]SAM (Fig. 3 A, lane 3). Similar results were observed with unlabeled SAM and detection by Western analysis using antisera to methylated Arg (data not shown). To directly test whether endogenous SHP in mouse liver is a target of posttranslational methylation by PRMT5, endogenous PRMT5 in mouse liver was depleted using adenoviral siRNA as described above (Fig. 2D), and then, methylation of endogenous SHP was detected by immunoprecipitation under stringent conditions with SDS-containing buffer, followed by Western analysis (Fig. 3B, top). Arg-methylated SHP levels were markedly decreased in PRMT5-depleted liver compared to control mice (Fig. 3B, bottom).

Fig. 3.

PRMT5 methylates SHP at Arg-57 after bile acid treatment. (A) (Top) GST-SHP or GST was incubated with purified PRMT5 and 3H-labeled S-adenosyl methionine, and methylated SHP was detected by autoradiography. (Bottom) Similar GST-SHP amounts were used in the reaction. (B) (Top) Experimental outline for in vivo SHP methylation assays. (Bottom) Hepatic PRMT5 was downregulated by adenovirus-expressed siRNA for PRMT5, and endogenous SHP was immunoprecipitated under stringent conditions using SDS-containing buffers. Arg-methylated SHP was detected by Western analysis. (C) Experimental outline for MS/MS analysis. Flag-human SHP was isolated from HepG2 cells treated with vehicle or CDCA for 1 h and incubated with PRMT5 and SAM. (D) Methylated SHP was detected by Western analysis. The membrane was stripped, and Flag-SHP and PRMT5 levels were determinted. (E) After in vitro methylation, proteins were separated by PAGE and visualized by colloidal staining. Flag-SHP bands (arrow) were excised for LC–MS-MS analysis. (F) MS/MS spectrum of the SHP peptide containing methylated Arg-57. (G) Experimental outline. HepG2 cells infected with Ad-Flag-SHP WT or Ad-Flag-R57W were treated with CDCA for 1 h, and Flag-SHP was isolated for in vitro assays. (H) 3H-methylated SHP was detected by autoradiography (top) and PRMT5 (middle) and f-SHP levels (bottom) by Western analysis and colloidal staining, respectively.

SHP methylation at Arg-57 by PRMT5 is substantially increased after CDCA treatment.

In order to determine the functional roles of posttranslational methylation of SHP, an Arg residue(s) methylated by PRMT5 was identified using MS-MS (Fig. 3C). Methylated SHP was dramatically increased by CDCA treatment of HepG2 cells (Fig, 3D, lane 4). Only methylation at Arg-57 was detected in purified SHP after CDCA treatment by tandem mass spectrometry (Fig. 3E and F). Arg-57 is highly conserved in mammals (data not shown), and intriguingly, a natural mutation, R57W, is associated with the metabolic syndrome in humans (7, 8, 27). Mutation of Arg-57 abolished the methylation of SHP (Fig. 3G and H), confirming that Arg-57 is the major site methylated by PRMT5. These proteomic and biochemical studies demonstrate that PRMT5 methylates SHP at Arg-57 and suggest that bile acid signaling substantially increases SHP methylation.

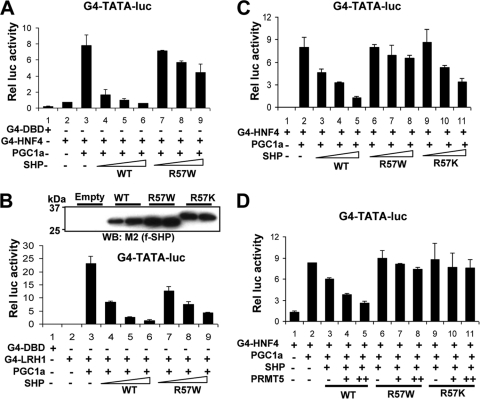

Arg-57 methylation augments the SHP repression function.

To test the functional relevance of Arg-57 methylation, the activity of the R57W SHP mutant was examined by cell-based reporter assays. Enhancement of SHP repression of HNF-4 (Fig. 4 A) and LRH1 (Fig. 4B) by the R57W mutant was substantially less than by the WT protein. The repression effects of SHP were markedly reduced, although not completely abolished, by a more conservative R57K mutation (Fig. 4C). The continued, but markedly decreased, effects of the R57K mutant suggest that methylation enhances, but is not absolutely required for, SHP activity. Further, these data strengthen the conclusion that decreased methylation of R57, rather than nonspecific conformational changes, largely contributes to decreased SHP activity. Comparable expression levels of WT SHP and the mutant proteins were detected, although the mobility of the R57K mutant was slightly altered (Fig. 4B, inset). Importantly, enhancement of SHP repression by PRMT5 was not observed with the R57W and R57K mutants (Fig. 4D). These results suggest that methylation at Arg-57 by PRMT5 augments the SHP repression function.

Fig. 4.

Arg-57 methylation is important for SHP repression activity. (A to D) HepG2 cells transfected with plasmids as indicated (for plasmid amounts, see Materials and Methods) were treated with CDCA overnight, and reporter assays were performed. The triangles represent increasing amounts of the Flag-SHP vectors. The values for firefly luciferase activities were normalized by dividing them by the β-galactosidase activities. The means and SEM are plotted (n = 3). In panel B, expression levels of Flag-SHP WT, R57W, and R57K from duplicate samples are shown at the top.

Methylation of SHP increases interactions with its known cofactors.

To identify the molecular mechanisms by which Arg-57 methylation augments SHP repression activity, we first tested whether methylation might stabilize SHP. The half-life of the R57W mutant, however, was similar to that of WT SHP, and if anything, the stability of the R57W mutant increased, since its steady-state levels were increased compared to those of the WT protein (Fig. 5 A). The decreased SHP activity of R57W thus cannot be explained by reduced protein stability.

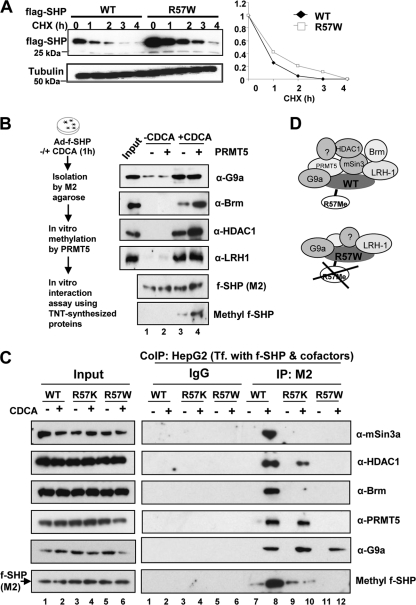

Fig. 5.

Mutation of R57 in SHP does not affect stability but selectively impairs interaction with its known chromatin-modifying cofactors. (A) HepG2 cells infected with Ad-Flag-SHP WT or R57W were treated with cycloheximide (CHX) (10 μg/ml), and Flag-SHP levels were detected by Western analysis. Band intensities were measured by densitometry, and the intensities relative to the 0-min time point were plotted (right). (B) (Left) Experimental outline. Flag-SHP was isolated by affinity binding to M2 agarose and incubated with the indicated proteins synthesized from the transcription and translation (TNT) system. (Right) Flag-SHP was immunoprecipitated, and SHP-interacting proteins and methylated SHP were detected by Western analysis. (C) HepG2 cells were cotransfected with expression plasmids for Flag-SHP WT or mutants as indicated. Proteins were immunoprecipated with M2 antibody for Flag or IgG control, and proteins in the immunoprecipitates were detected by Western analysis using each of the indicated antibodies or SYM10 for methylated SHP. (D) Schematic diagram of transcription regulators interacting with Flag-SHP WT (top) or the R57W mutant (bottom).

Next, we examined whether methylation of SHP increases interaction with its known chromatin-modifying repressive cofactors, mSin3A, HDAC1, G9a, and Brm (9, 16, 25). Interaction with a well-known SHP-interacting DNA binding factor, LRH-1, was also examined. Flag-SHP was isolated from untreated or CDCA-treated HepG2 cells and incubated in vitro with PRMT5. Treatment of cells with CDCA resulted in increased methylation of SHP and interaction with its cofactors (Fig. 5B, lane 3) and substantially increased the in vitro methylation of SHP by PRMT5 (Fig. 5B, lane 4). The increased methylation correlated with increased interactions of SHP with Brm and HDAC1, but not with G9a and LRH-1 (Fig. 5B). These results suggest that increased methylation of SHP by CDCA treatment selectively increases its interaction with cofactors.

To further test if R57 methylation is important for increased interaction between SHP and its cofactors, we performed CoIP studies using the R57K and R57W mutants. HepG2 cells were transfected with expression plasmids for Flag-SHP and its cofactors, and the interactions between SHP and these cofactors were examined. CDCA treatment dramatically increased the methylation of WT SHP and interaction with mSin3A, HDAC1, Brm, PRMT5, and G9a (Fig. 5C). In contrast, these increased interactions were not observed with R57W and largely decreased with the R57K mutant. Consistent with in vitro CoIP studies (Fig. 5B), decreased SHP interaction with G9a was not observed with R57K and R57W (Fig. 5C and data not shown), suggesting that G9a is present in a SHP complex in hepatic cells and that this interaction is independent of methylation at Arg-57. These data demonstrate that methylation of SHP is important for enhanced interaction with some, but not all, of its cofactors (Fig. 5D).

Occupancy of PRMT5 and SHP at the Cyp7a1 promoter in vivo is increased after bile acid treatment.

To test whether PRMT5 occupancy at the Cyp7a1 promoter, a well-known SHP target (4, 12, 22, 30), is increased after bile acid treatment in mouse liver and whether the Cyp7a1 promoter is cooccupied by SHP and PRMT5, we performed re-ChIP assays. Chromatin was immunoprecipitated first with SHP antisera, and then, eluted chromatin was reprecipitated with antisera to PRMT5 and other known SHP-interacting cofactors. Occupancy of SHP, PRMT5, G9a, and Brm at the promoter was increased by CA feeding, while that of the transcriptional activity marker RNA polymerase II was decreased (Fig. 6 A). Occupancy of PRMT5 at the human CYP7A1 gene promoter was also increased after CDCA treatment of HepG2 cells (Fig. 6B). These results suggest that PRMT5, as well as G9a, Brm, and SHP, are recruited to the Cyp7a1 promoter after bile acid treatment in vivo, resulting in gene repression.

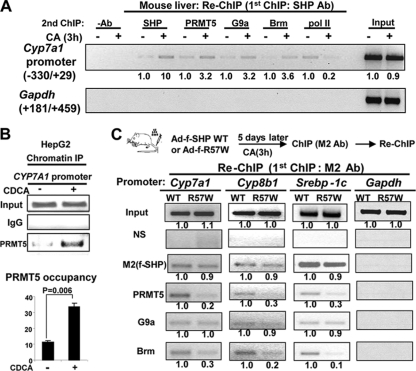

Fig. 6.

Mutation of R57 in SHP impairs recruitment of Brm and PRMT5, but not G9a, to metabolic target genes. (A) Mice were fed normal or CA chow, and re-ChIP assays were performed. Chromatin was first immunoprecipitated with SHP antibody, eluted, and then reprecipitated with a second antibody as indicated. Semiquantitative PCR was performed to detect occupancy at the Cyp7a1 promoter (top) and the control GAPDH (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase) coding region (bottom). Band intensities were determined using Image J, with the values for control samples from mice fed normal chow set to 1 (below). Consistent results were observed for two re-ChIP assays. (B) HepG2 cells were treated with 50 μM CDCA for 3 h, and ChIP assays were performed. Band intensities were measured, and the intensities relative to those of untreated samples were plotted with the SEM (n = 3) indicated (bottom). (C) Mice were injected via tail veins with Ad-Flag-SHP WT or the R57W mutant and 5 days later were fed CA chow for 3 h. Livers were then collected for re-ChIP assays. Chromatin was first immunoprecipitated with M2 antibody, eluted, and then reprecipitated with the indicated antibody (left). NS, normal serum. Semiquantitative PCR was performed to detect occupancy of the proteins at the Cyp7a1, Cyp8b1, and Srebp-1c gene promoters, with the GAPDH coding region as a control. Band intensities were determined using Image J, with values for samples from mice infected with Ad-SHP WT set to 1 (below).

A methylation-defective R57W mutant shows impaired recruitment of its cofactors to metabolic target genes.

Using re-ChIP assays in mouse livers expressing Flag-SHP WT or the R57W mutant, we next examined the effect of the R57W mutation on recruitment of SHP cofactors to the promoters of three well-known metabolic target genes, the Cyp7a1, Cyp8b1, and Srebp-1c genes (9, 16, 25, 31, 38). At each promoter, similar occupancy of Flag-SHP or R57W was detected, which is consistent with similar interactions of both to the DNA binding protein LRH-1 (Fig. 5B). Occupancy of PRMT5 and Brm was markedly decreased with the R57W mutant for all three genes (Fig. 6C). Consistent with the CoIP studies (Fig. 5C), occupancy of G9a at these promoters was not decreased in mice expressing the R57W mutant (Fig. 6C), suggesting that Arg-57 methylation is not required for G9a recruitment. These in vivo re-ChIP studies, together with CoIP studies (Fig. 5C), suggest that methylation of Arg-57 is important for interaction of SHP with HDAC1 and Brm, but not with G9a, and recruitment of these cofactors to SHP's target gene promoters.

Hepatic overexpression of the R57W mutant reverses repression of SHP metabolic targets in a gene-selective manner.

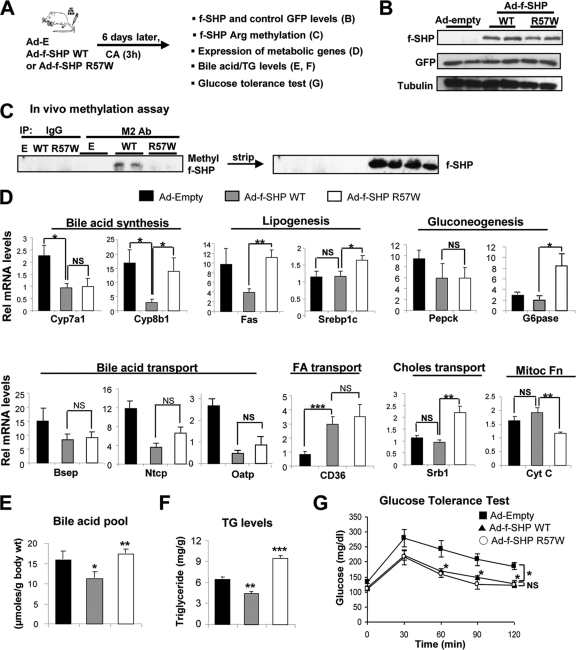

To determine the physiological significance of Arg-57 methylation in metabolic regulation, the effects of the methylation-defective R57W mutant on mRNA levels of SHP target metabolic genes was examined in vivo using adenoviral expression vectors (Fig. 7 A). As in the cell culture studies (Fig. 3H), methylation of SHP was severely impaired in mice expressing the R57W mutant compared to the WT (Fig. 7B and C). Hepatic expression of SHP WT led to decreased expression of the bile acid biosynthetic Cyp7a1 and Cyp8b1 genes, the lipogeneic Fas and Srebp-1c genes, and the bile acid transporter Bsep and Ntcp genes (Fig. 7D), as previously reported (1, 3). Exogenous expression of SHP WT decreased expression of the gluconeogenic Pepck and G-6-pase genes, but the effects were not statistically significant. Interestingly, mutation of Arg-57 reversed the effects in some target genes, but not others, like Cyp7a1 (Fig. 7D and data not shown), suggesting Arg-57 methylation affects SHP function in a gene-specific manner. Consistent with gene expression studies, liver triglyceride levels and the total bile acid pool were decreased in mice exogenously expressing SHP WT protein but substantially elevated in mice expressing the R57W mutant (Fig. 7E and F). In contrast, glucose and insulin tolerance were similarly increased in mice overexpressing either SHP WT or the R57W mutant (Fig. 7G and data not shown). These in vivo studies demonstrate a novel function of PRMT5 as a critical regulator of SHP in metabolic function and further suggest that R57 methylation by PRMT5 may contribute to gene-specific and perhaps metabolic-pathway-specific repression, possibly by differential interaction with and recruitment of known SHP chromatin-modifying cofactors (Fig. 5 and 6).

Fig. 7.

Hepatic overexpression of the methylation-defective R57W mutant reverses repression of known SHP metabolic targets in a gene-selective manner. (A) Experimental outline. (B) Protein levels in liver extracts were detected by Western analysis. (C) Flag-SHP was immunoprecipitated, and methylated SHP was detected by Western analysis using SYM10 antibody in duplicate samples. (D) Expression of SHP target genes in different metabolic pathways was detected by qRT-PCR. The mean and SEM (n = 5) are shown. FA, fatty acid; Choles, cholesterol; Mitoc fn, mitochondrial function; Cyt C, cytochrome c. (E and F) Total bile acid pool levels in liver, gallbladder, and intestines and liver triglyceride levels were measured (n = 5). (G) Glucose tolerance tests in mice infected with control Ad-empty, Ad-SHP WT, or Ad-R57W (n = 3 to 4). The means and SEM are plotted. Statistical significance was measured using Student's t test. *, **, ***, and NS indicate P values of <0.05, <0.01, and <0.001 and statistically not significant, respectively.

DISCUSSION

Our studies have identified PRMT5 as an important in vivo regulator of SHP in metabolic function. First, proteomic and CoIP studies revealed that the interaction of PRMT5 with SHP was dramatically increased in the liver in response to bile acid signaling. Second, tandem mass spectrometry and biochemical studies showed that methylation of SHP at Arg-57 by PRMT5 was substantially increased after bile acid treatment. Third, re-ChIP and CoIP studies revealed that mutation of Arg-57 led to selectively decreased interaction of SHP with Brm, mSin3A, and HDAC1, but not with G9a, and subsequent recruitment of these cofactors to SHP's target genes. Finally, functional in vivo experiments showed that hepatic overexpression of methylation-defective R57W or depletion of PRMT5 both reversed the repression of SHP metabolic target genes in a gene-selective manner. Consistent with gene expression studies, the inhibitory effects of SHP WT on bile acid pool and liver triglyceride levels were impaired with the mutation of Arg-57, but interestingly, the effects on glucose and insulin tolerance were not altered.

Naturally occurring heterozygous mutations, including R57W, in the SHP gene have been reported in humans with type II diabetes, obesity, and fatty liver (7, 8, 27), confirming the important metabolic functions of SHP. The effects of the R57W mutation on gene expression and triglyceride and bile acid levels in mice are consistent with its association with human metabolic disease. Hepatic expression of the R57W mutant markedly increased lipogenic and bile acid synthetic gene expression in comparison to expression of wild-type SHP. These changes in gene expression resulted in elevated hepatic triglyceride and total bile acid pool levels. Similar effects were observed with the depletion of PRMT5, which further strengthens the conclusion that PRMT5 enhances the SHP repression function by methylation of Arg-57. In addition, conformational changes in R57W may contribute to the reduced activity of SHP, since the more conservative R57K mutation resulted in smaller effects on SHP activity. Taken together, these results provide a possible explanation of why the R57W mutation is associated with metabolic syndrome in humans.

How transcription factors regulate their target genes in a gene-specific manner has been a longstanding question. PTMs, including methylation, may provide distinct protein-interacting interfaces that allow differential interaction with transcriptional cofactors and may contribute to gene-specific regulation (15, 17, 21). Previous studies have shown that posttranslational methylation of p53 by PRMT5 is important for determining whether cells enter cell cycle arrest or apoptosis by repressing different sets of target genes (15). In this study, we found that mutation of Arg-57 reversed the suppression of some, but not all, metabolic genes by SHP in mouse liver. Such gene-specific effects may be partly due to differential interaction of methylated SHP with its cofactors, as observed from CoIP and re-ChIP studies. For example, regulation of genes specifically dependent on the cofactor G9a, such as the Cyp7a1 gene (9), might be independent of Arg-57 methylation, since the mutation does not reduce levels of G9a in the SHP complex. In contrast, regulation of genes more dependent on the cofactors Brm and HDAC1, such as the Cyp8b1 and Srebp1-c genes, would be affected by methylation, since mutation of Arg-57 reduces the interaction of SHP with these cofactors. Similar effects were observed with both the R57W mutant of SHP (Fig. 7D) and the downregulation of PRMT5 (Fig. 2F), which provides strong evidence that PRMT5-catalyzed Arg methylation enhances SHP repression of metabolic genes. An exception was the effects on Cyp7a1, for which the R57W mutant was similar to wild-type SHP (Fig. 7D), while downregulation of PRMT5 increased Cyp7a1 expression (Fig. 2F). PRMT5 may regulate Cyp7a1 by other indirect mechanisms in addition to methylation of Arg-57 in SHP, such as histone methylation at the target genes.

The activities of most nuclear receptors are regulated by ligand binding (23), but SHP was discovered as an orphan receptor (32), and its endogenous ligand is not known. In this regard, modulation of SHP activity by PTMs in response to physiological stimuli would be an effective alternative way to control its activity and/or stability. SHP is a well-known component of cellular sensor systems for bile acid signaling (1, 3). Bile acids not only play dietary roles in the absorption of fat-soluble nutrients, but also function as endocrine signaling molecules that trigger genomic and nongenomic signaling pathways (4, 13, 30, 33). We recently reported that bile acid signaling activates ERK, which phosphorylates SHP at Ser-26, which increases SHP stability in hepatocytes (26). Thus, in addition to SHP gene induction by the bile acid-activated nuclear receptor FXR (12, 22), modulation of SHP stability and repression activity by PTMs are likely to be important in the mediation of bile acid signaling by SHP. To our knowledge, this study is the first demonstration that SHP repression activity is increased by posttranslational modification in response to bile acid signaling.

Since this study demonstrates increased methylation of SHP in response to elevated bile acid levels, it will be important to determine whether a specific kinase(s) in bile acid signaling pathways is involved in Arg methylation by PRMT5 and whether methylation of SHP affects or is affected by other PTMs. FGF15/19 signaling is activated in response to elevated bile acid levels in the enterohepatic system in vivo (14), so it will also be important to determine whether FGF15/19 signaling enhances SHP activity via Arg methylation by PRMT5. Furthermore, it will be interesting to determine whether decreased methylation of SHP is associated with metabolic disease, which is analogous to our recent findings that acetylation of FXR is normally dynamically regulated by p300 acetylase and SIRT1 deacetylase but highly elevated in metabolic disease states (17, 18).

SHP plays an important role in controlling lipid and glucose levels by inhibiting metabolic target genes in the liver and other metabolic tissues and is also involved in cell proliferation, apoptosis, and reproduction (1, 3, 11, 35, 36, 39). Given that SHP plays important roles in such diverse mammalian physiology, PTMs may provide a mechanism for selective regulation of genes in biological processes. Further, targeting posttranslational modifications of SHP may be an effective therapeutic strategy by controlling selected groups of genes to treat SHP-related human diseases, such as metabolic syndrome, cancer, and infertility.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Bert Vogelstein for the adenoviral expression system, Richard Gaynor for PRMT5 expression plasmids, Stephane Richard for pSuper-si-PRMT5, Johan Auwerx for GST-SHP constructs, and Anthony Imbalzano and Said Sif for the Brm and Brg-1 expression plasmids. We also thank B. Kemper for helpful comments on the manuscript.

This study was supported by NIH DK062777, NIH DK080032, and an American Diabetes Association Basic Science Award to J.K.K. This project has been funded in whole or in part with federal funds from the National Cancer Institute and the National Institutes of Health and under contract N01-CO-12400 to T.D.V.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 24 January 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Båvner A., Sanyal S., Gustafsson J. A., Treuter E. 2005. Transcriptional corepression by SHP: molecular mechanisms and physiological consequences. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 16:478–488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bedford M. T., Clarke S. G. 2009. Protein arginine methylation in mammals: who, what, and why. Mol. Cell 33:1–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chanda D., Park J. H., Choi H. S. 2008. Molecular basis of endocrine regulation by orphan nuclear receptor Small Heterodimer Partner. Endocr. J. 55:253–268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chiang J. Y. 2004. Regulation of bile acid synthesis: pathways, nuclear receptors, and mechanisms. J. Hepatol. 40:539–551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dacwag C. S., Bedford M. T., Sif S., Imbalzano A. N. 2009. Distinct protein arginine methyltransferases promote ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling function at different stages of skeletal muscle differentiation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 29:1909–1921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dacwag C. S., Ohkawa Y., Pal S., Sif S., Imbalzano A. N. 2007. The protein arginine methyltransferase Prmt5 is required for myogenesis because it facilitates ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling. Mol. Cell. Biol. 27:384–394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Echwald S. M., et al. 2004. Mutation analysis of NR0B2 among 1545 Danish men identifies a novel c. 278G>A (p.G93D) variant with reduced functional activity. Hum. Mutat. 24:381–387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Enya M., et al. 2008. Mutations in the small heterodimer partner gene increase morbidity risk in Japanese type 2 diabetes patients. Hum. Mutat. 29:E271–E277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fang S., et al. 2007. Coordinated recruitment of histone methyltransferase G9a and other chromatin-modifying enzymes in SHP-mediated regulation of hepatic bile acid metabolism. Mol. Cell. Biol. 27:1407–1424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fang S., et al. 2008. The p300 acetylase is critical for ligand-activated farnesoid X receptor (FXR) induction of SHP. J. Biol. Chem. 283:35086–35095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Farhana L., et al. 2007. Adamantyl-substituted retinoid-related molecules bind small heterodimer partner and modulate the Sin3A repressor. Cancer Res. 67:318–325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Goodwin B., et al. 2000. A regulatory cascade of the nuclear receptors FXR, SHP-1, and LRH-1 represses bile acid biosynthesis. Mol. Cell 6:517–526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hylemon P. B., et al. 2009. Bile acids as regulatory molecules. J. Lipid Res. 50:1509–1520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Inagaki T., et al. 2005. Fibroblast growth factor 15 functions as an enterohepatic signal to regulate bile acid homeostasis. Cell Metab. 2:217–225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jansson M., et al. 2008. Arginine methylation regulates the p53 response. Nat. Cell Biol. 10:1431–1439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kemper J., Kim H., Miao J., Bhalla S., Bae Y. 2004. Role of a mSin3A-Swi/Snf chromatin remodeling complex in the feedback repression of bile acid biosynthesis by SHP. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24:7707–7719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kemper J. K. Regulation of FXR transcriptional activity in health and disease: Emerging roles of FXR cofactors and post-translational modifications. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, in press [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18. Kemper J. K., et al. 2009. FXR acetylation is normally dynamically regulated by p300 and SIRT1 but constitutively elevated in metabolic disease states. Cell Metab. 10:392–404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kerr T. A., et al. 2002. Loss of nuclear receptor SHP impairs but does not eliminate negative feedback regulation of bile acid synthesis. Dev. Cell 2:713–720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kwak Y. T., et al. 2003. Methylation of SPT5 regulates its interaction with RNA polymerase II and transcriptional elongation properties. Mol. Cell 11:1055–1066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lee Y. H., Stallcup M. R. 2009. Minireview: protein arginine methylation of nonhistone proteins in transcriptional regulation. Mol. Endocrinol. 23:425–433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lu T. T., et al. 2000. Molecular basis for feedback regulation of bile acid synthesis by nuclear receptors. Mol. Cell 6:507–515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mangelsdorf D. J., Evans R. M. 1995. The RXR heterodimers and orphan receptors. Cell 83:841–850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Miao J., Fang S., Bae Y., Kemper J. K. 2006. Functional inhibitory cross-talk between car and HNF-4 in hepatic lipid/glucose metabolism is mediated by competition for binding to the DR1 motif and to the common coactivators, GRIP-1 and PGC-1alpha. J. Biol. Chem. 281:14537–14546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Miao J., et al. 2009. Functional specificities of Brm and Brg-1 Swi/Snf ATPases in the feedback regulation of hepatic bile acid biosynthesis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 29:6170–6181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Miao J., et al. 2009. Bile acid signaling pathways increase stability of Small Heterodimer Partner (SHP) by inhibiting ubiquitin-proteasomal degradation. Genes Dev. 23:986–996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Nishigori H., et al. 2001. Mutations in the small heterodimer partner gene are associated with mild obesity in Japanese subjects. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98:575–580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Pal S., et al. 2003. mSin3A/histone deacetylase 2- and PRMT5-containing Brg1 complex is involved in transcriptional repression of the Myc target gene cad. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23:7475–7487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Richard S., Morel M., Cleroux P. 2005. Arginine methylation regulates IL-2 gene expression: a role for protein arginine methyltransferase 5 (PRMT5). Biochem. J. 388:379–386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Russell D. W. 2003. The enzymes, regulation, and genetics of bile acid synthesis. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 72:137–174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sanyal S., et al. 2007. Involvement of corepressor complex subunit GPS2 in transcriptional pathways governing human bile acid biosynthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104:15665–15670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Seol W., Choi H., Moore D. D. 1996. An orphan nuclear hormone receptor that lacks a DNA binding domain and heterodimerizes with other receptors. Science 272:1336–1339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Thomas C., Pellicciari R., Pruzanski M., Auwerx J., Schoonjans K. 2008. Targeting bile-acid signalling for metabolic diseases. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 7:678–693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Vagin V. V., et al. 2009. Proteomic analysis of murine Piwi proteins reveals a role for arginine methylation in specifying interaction with Tudor family members. Genes Dev. 23:1749–1762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Volle D. H., et al. 2009. The orphan nuclear receptor small heterodimer partner mediates male infertility induced by diethylstilbestrol in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 119:3752–3764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Volle D. H., et al. 2007. The small heterodimer partner is a gonadal gatekeeper of sexual maturation in male mice. Genes Dev. 21:303–315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wang L., et al. 2002. Redundant pathways for negative feedback regulation of bile acid production. Dev. Cell 2:721–731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Watanabe M., et al. 2004. Bile acids lower triglyceride levels via a pathway involving FXR, SHP, and SREBP-1c. J. Clin. Invest. 113:1408–1418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Zhang Y., et al. 2010. Nuclear receptor SHP, a death receptor that targets mitochondria, induces apoptosis and inhibits tumor growth. Mol. Cell. Biol. 30:1341–1356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]