Abstract

Background

Lymph node metastases are prognostically significant in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Little is known about the significance of direct lymph node invasion.

Aim

The aim of this study is to find out whether direct lymph node invasion has the same prognostic significance as regional nodal metastases.

Methods

Retrospective review of patients resected between 1/1/1993 and 7/31/2008. “Direct” was defined as tumor extension into adjacent nodes, and “regional” was defined as metastases to peripancreatic nodes.

Results

Overall, 517 patients underwent pancreatic resection for adenocarcinoma, of whom 89 had one positive node (direct 26, regional 63), and 79 had two positive nodes (direct 6, regional 68, both 5). Overall, survival of node-negative patients was improved compared to patients with positive nodes (N0 30.8 months vs. N1 16.4 months; p<0.001). There was no survival difference for patients with direct vs. regional lymph node invasion (p=0.67). Patients with one positive node had a better overall survival compared to patients with ≥2 positive nodes (22.3 and 15 months, respectively; p<0.001). The lymph node ratio (+LN/total LN) was prognostically significant after Cox regression (p<0.001).

Conclusions

Isolated direct invasion occurs in 20% of patients with one to two positive nodes. Node involvement by metastasis or by direct invasion are equally significant predictors of reduced survival. Both the number of positive nodes and the lymph node ratio are significant prognostic factors.

Keywords: Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, Direct lymph node invasion, Lymph node ratio

Introduction

Pancreatic cancer is the fourth leading cause of cancer death in the USA. The American Cancer Society estimates that 42,470 people will be diagnosed with pancreatic cancer and 35,240 will die of the disease in 2009.1 Approximately 10–20% of patients diagnosed with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma harbor resectable tumors. However, overall survival continues to be poor even for resected patients, with a median survival of 17 to 18 months and a 5-year survival of 12–18%.2–6

Many studies have documented the prognostic significance of positive lymph nodes. Patients with lymph node metastases have a significantly lower 5-year survival rate than patients with node negative disease.3–5,7 The number of positive lymph nodes also appears to influence patient survival with two or more positive nodes associated with a worse outcome.6,8 Prospective randomized trials have evaluated the role of extended lymph node dissections. Despite the increased number of lymph nodes resected, there was no survival benefit but an increased morbidity.9–11

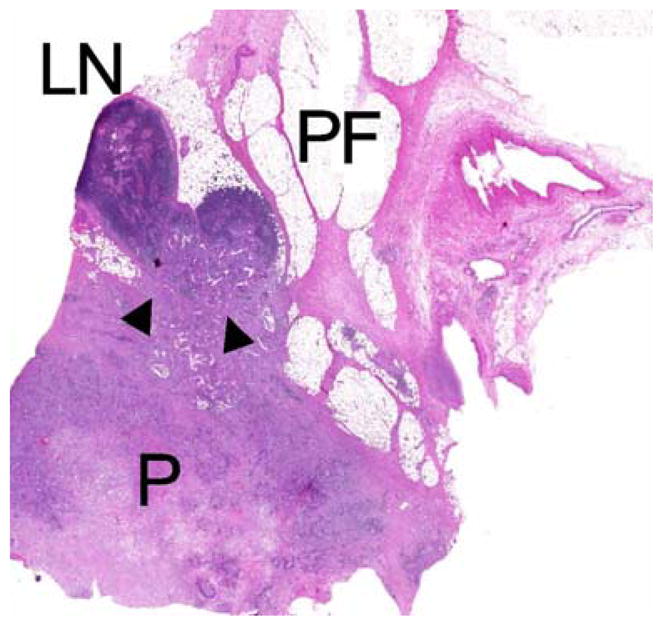

There are no studies addressing the significance of direct lymph node invasion by pancreatic adenocarcinoma (Fig. 1). Our first aim was to determine the frequency and prognostic impact of direct lymph node invasion. Our second aim was to determine the impact of the lymph node ratio (LNR, ratio of positive nodes to total nodes) on overall survival.

Figure 1.

In direct invasion (arrowheads) the tumor is directly invading lymph nodes situated in the peripancreatic fat (P pancreas, PF peripancreatic fat, LN lymph node).

Materials and Methods

Study Design

Review of a retrospectively created database (1/1/1993–1/1/2001) and a prospectively maintained database (1/1/2001–7/31/2008) was performed to identify patients who underwent surgical resection of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma arising within intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms were excluded. Clinical data evaluated included gender, age, race, family history, presenting symptoms (presence of abdominal pain and jaundice), operative procedures, neoadjuvant and adjuvant therapy, and disease-specific survival. Pathological data evaluated included TNM stage, size of the tumor, histological type, degree of differentiation, perineural, lymphatic, perivascular invasion, and surgical margin status. Tumors were graded as poorly, moderately, or well differentiated. Operative mortality was defined as death within 30 days of the operation. Overall survival was measured from the date of surgery until the time of death or last follow-up. Patients were staged according to the AJCC 6th edition.

Patients with positive lymph nodes were divided into two groups, direct and regional. Direct invasion of a node by tumor was defined by the presence of a continuous column of tumor cells extending from the intra- or extrapancreatic portion of the primary lesion to the involved lymph node. Regional nodal metastasis lacked this continuity between the primary pancreatic lesion and the lymph node. For lymph nodes directly invaded by the tumor, the available pathology slides were reviewed by a single GI pathologist (V.D.). For node-positive patients, the ratio of the number of positive nodes to the total number of nodes resected was calculated (LNR). The period from 1/1/1993 to 7/31/2008 was divided into three time periods (A: 1993–1997, B: 1998–2002, and C: 2003–2008) in order to assess changes in the number of assessed lymph nodes.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Massachusetts General Hospital.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis of the data was done utilizing SPSS 11.0 for windows (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, Inc., Chicago, IL). Continuous variables including age, tumor size, and LNR were dichotomized at their median values for the purpose of statistical analysis. Comparisons for continuous variables with normal distributions were conducted with the t test and for continuous variables without normal distributions by the Mann–Whitney test or Kruskal–Wallis test. Categorical variables were analyzed using the chi-square test. Survival curves were constructed with the Kaplan–Meier method. Univariate comparisons were performed with the log-rank method. Cox proportional hazards model was used for those factors found to be significant in the univariate analysis. Level of statistical significance was set at p=0.05.

Results

Clinicopathologic Characteristics

A total of 517 patients underwent resection for a pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, of whom 52.8% were females. The clinicopathologic characteristics of the patients and the operations performed are listed in Table 1. The median age of the cohort was 67 years old. Pancreaticoduodenectomy was the most frequent operation performed (84.3%). The majority of patients (67.5%) had Stage IIB disease with a median tumor size of 3 cm (range 0.3–12.5 cm).

Table 1.

Clinicopathologic Characteristics of 517 Patients with Resected Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma

| All Patients | Direct | Regional | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients (%) | 517 | 32 | 131 | |

| Age median (range) | 67 (33–90) | 69.5 (47–82) | 68 (43–90) | 0.85 |

| Female gender | 273 (52.8) | 21 (65.6) | 66 (50.3) | 0.12 |

| Abdominal pain | 225 (43.5) | 13 (40.6) | 54 (41.2) | 0.94 |

| Jaundice | 345 (66.7) | 21 (65.6) | 83 (63.3) | 0.64 |

| Operations | ||||

| Pancreaticoduodenectomy | 436 (84.3) | 25 (78.1) | 109 (83.2) | 0.5 |

| Distal pancreatectomy | 73 (14.1) | 7 (21.9) | 22 (16.8) | |

| Total pancreatectomy | 8 (1.5) | 0 | 0 | |

| Surgical margins R0 | 360 (69.6) | 24 (75) | 97 (74) | 0.91 |

| Median tumor size, cm (range) | 3 (0.3–12.5) | 2.6 (1–7) | 3 (0–7) | 0.43 |

| T stage | ||||

| T1 | 19 (3.7) | 0 | 1 (0.8) | 0.23 |

| T2 | 40 (7.7) | 0 | 10 (7.6) | |

| T3 | 458 (88.6) | 32 (100) | 120 (91.6) | |

| Grade | ||||

| Well | 18 (3.5) | 1 (3.1) | 6 (4.6) | 0.75 |

| Mod | 282 (54.5) | 19 (59.4) | 67 (51.1) | |

| Poor | 205 (39.7) | 12 (37.5) | 55 (42) | |

| Other (not assessed, undifferentiated, mixed types) | 12 (2.3) | 0 | 3 (2.3) | |

| Perineural invasion | 407 (78.7) | 30 (93.7) | 104 (79.4) | 0.05 |

| Lymphatic invasion | 220 (42.6) | 17 (53.1) | 55 (42) | 0.25 |

| Vascular invasion | 222 (42.9) | 13 (40.6) | 52 (39.7) | 0.92 |

Patients with one or two positive nodes are divided into direct and regional (p values reflect the comparison between direct and regional LN groups with one or two positive nodes)

The postoperative mortality was 0.8%. Median and mean follow-up were 16 and 24.9 months, respectively (range 0–166 months). The median survival for the entire cohort (n=517) was 19.7 months, and the 5-year actuarial survival was 17.3%. Patients with node-positive disease (n=349) had a statistically significant decrease in median and 5-year survival compared to patients with node-negative disease (n=168) (16.4 versus 30.8 months and 5-year actuarial survival of 9% versus 31%, respectively; p<0.001).

Patterns of Lymph Node Involvement: Direct Invasion versus Regional

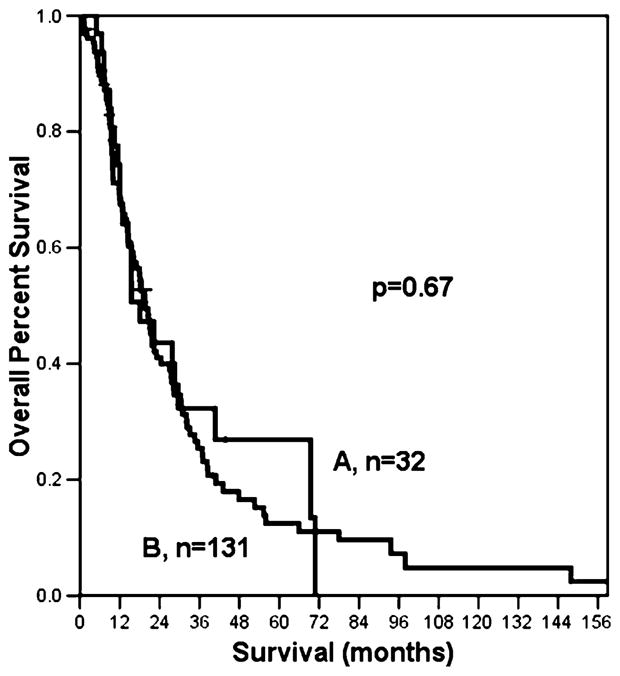

The clinicopathologic characteristics of patients with direct lymph node invasion and positive regional lymph nodes were similar (Table 1). A single positive lymph node was identified in 89 patients (17.2%). Direct node invasion was present in 26 patients (29.2%), and a positive regional node was present in 63 patients (70.8%). Two positive lymph nodes were identified in 79 patients (15.3%). Direct invasion of both nodes occurred in six patients (7.6%), two positive regional nodes were identified in 68 patients (86%), and five patients had both direct and regional nodes (6.3%). No patients with three or more positive lymph nodes had all their nodes directly invaded by the tumor. Therefore, we limited our analysis to patients with one or two positive nodes. Patients who had both direct and regional lymph node involvement were also excluded from further analysis. The location of the tumor (head versus body/tail) did not differ significantly between patients with one or two directly invaded nodes (p=0.43). Overall survival for patients with one or two directly invaded nodes was not significantly different from patients with one or two positive regional nodes (p=0.67; Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Patients with one or two positive nodes have similar survival whether the node is directly invaded by the tumor (A), or is a regional node (B).

Number of Lymph Nodes and Survival

The median number of pathologically examined lymph nodes for all patients was 13 (range 1–49). The number of nodes evaluated increased over time (Table 2).

Table 2.

Factors Influencing the Number of Assessed Lymph Nodes

| (Parameter) | Median Number of LNs | P value |

|---|---|---|

| Time period | ||

| 1993–1997 (105) | 9 | <0.001 |

| 1998–2002 (161) | 13 | |

| 2003–2008 (251) | 15 | |

| Operation | ||

| Whipple (436) | 14 | 0.1 |

| Distal pancreatectomy (73) | 12 | |

| Total pancreatectomy (8) | 19 | |

| Tumor stage | ||

| Intrapancreatic (T1,T2) (59) | 13 | 0.26 |

| Extrapancreatic (T3) (458) | 14 | |

| Nodal status | ||

| N0 (168) | 10 | <0.001 |

| N1 (349) | 15 | |

Node-negative patients had a median survival of 30.8 months, a 5-year survival of 31% and a median number of 10 lymph nodes assessed. In node-negative patients, overall survival did not differ between those who had ≥10 nodes evaluated (n=85) and patients with <10 nodes evaluated (n= 83; p=0.69). However, patients who were node-negative with <10 nodes had a survival approaching that of patients with one positive node (p=0.11).

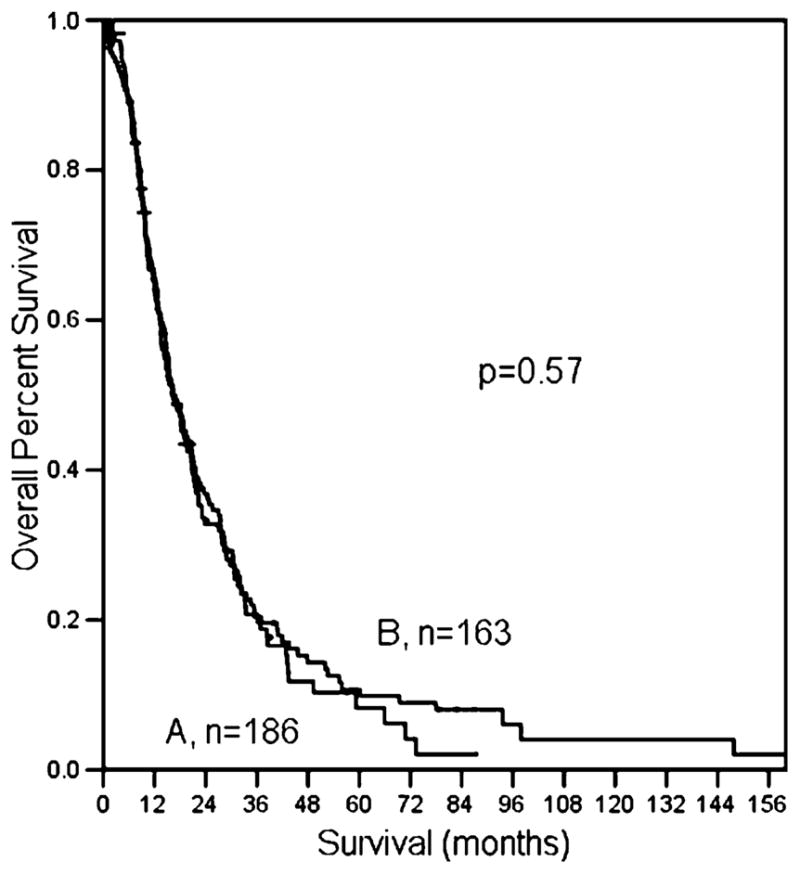

Node-positive patients had a median survival of 16.4 months and a 5-year survival of 9%. For patients with node-positive disease, the median number of assessed lymph nodes was 15. The overall median survival for these patients was 16.4 months whether or not they had <15 nodes assessed (p=0.5, Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Median number of nodes evaluated in patients with positive nodes does not affect survival. A Total number of resected nodes ≥15; B N1 patients with resected nodes <15.

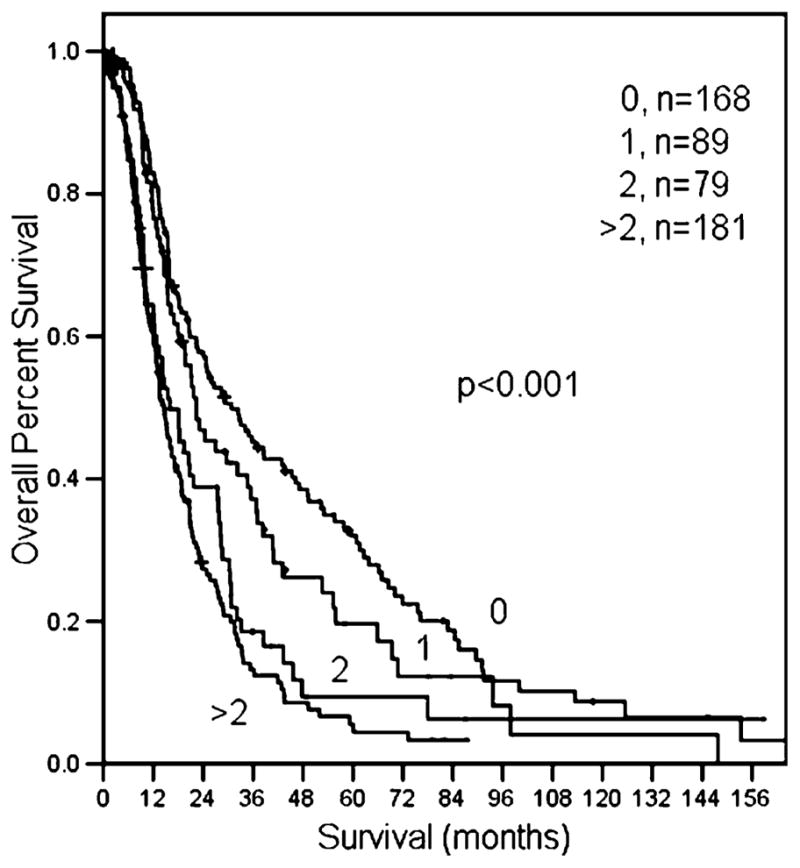

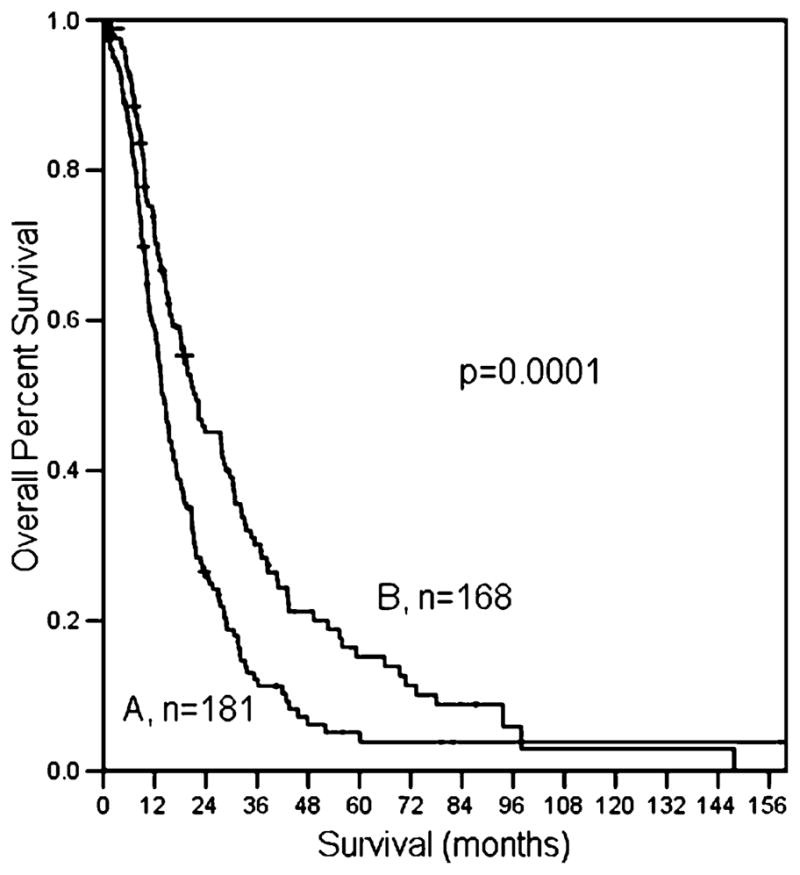

The median number of positive lymph nodes was 3. Patients with a single positive node had a significantly better survival than patients with two or more positive nodes (22.3 months for one positive node vs. 16 months for two positive nodes vs. 15 months for >2 positive nodes; log rank, p<0.001, Fig. 4). The median lymph node ratio was 0.2. The survival of patients with a LNR of ≥0.2 (n= 181) was significantly worse than patients with a LNR< 0.2 (n=168; 14 vs. 22 months, respectively, p<0.001; Fig. 5).

Figure 4.

Patients with negative nodes have a better prognosis compared to patients with one, two, or more than two positive nodes.

Figure 5.

The influence of LNR on overall survival; A LNR≥0.2; B LNR<0.2.

Multivariate Survival Analysis

For the entire cohort of 517 patients, the median survival was 19.7 months, and the 5-year actuarial survival was 17.3%. On univariate analysis, predictors of survival were: size and differentiation of the tumor, presence of lymphatic and perivascular invasion, negative surgical margins (R0), and LNR.

Patients harboring well-differentiated tumors less than 3 cm in size, with no evidence of perivascular or lymphatic invasion and a LNR less than 0.2 that were resected with microscopically negative surgical margins had the most favorable outcome. After Cox proportional hazards multivariate analysis, LNR remained the most significant prognostic factor for survival (Table 3).

Table 3.

Univariate and Multivariate Analysis of Prognostic Factors

| Factor | Univariate P value | Multivariate P value |

|---|---|---|

| Size≥3 cm | <0.0001 | 0.003 |

| Differentiation | 0.044 | 0.003 |

| LNR≥0.2 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Perivascular Invasion | 0.0002 | 0.06 |

| Lymphatic Invasion | 0.0047 | 0.19 |

| R0 | <0.0001 | 0.005 |

Discussion

Lymph node involvement by cancer is consistently a significant prognostic factor for overall survival in patients with resected pancreatic adenocarcinoma.3–7 In this report, node-negative patients experienced a 5-year actuarial survival of 31%, whereas node-positive patients had a 5-year actuarial survival of 9%. While many studies outline the importance of lymph node involvement, no prior studies address the impact of direct tumor extension into lymph nodes.

Direct lymph node invasion was documented in 29.2% of patients with a single positive node and in 7.6% of patients with two positive nodes. The probability of identifying direct lymph node invasion by the tumor was similar for resected cancers located in the head, body, and tail of the pancreas. Patients with positive regional nodes can harbor earlier stage tumors (T1/T2) than patients with extrapancreatic extension of the tumor into lymph nodes (T3). However, there was no survival difference between patients with positive direct or regional nodes.

Increased awareness of the prognostic significance of lymph node positivity has led to improved lymph node retrieval. In our cohort, the median number of examined nodes increased progressively from 1993 to 2008. A significantly larger number of nodes were retrieved in node-positive patients, which has been described in other surgical series as well.6,12

In our study, evaluating more lymph nodes than the median number of nodes was not associated with improved survival in either the N0 or N1 groups. Node-negative patients had a survival of 30.8 months, similar to the 25.3 months in the series by Pawlik et al.13 and 27 months in the series by House et al.6 The survival benefit of node-negative disease seems to be lost when the patient is characterized as node-negative based on a small number of assessed lymph nodes. House et al.6 reported that patients characterized as N0 based on less than 12 nodes had a similar survival to patients with a single positive node and more than 12 nodes assessed. We similarly found that patients characterized as node-negative based on less than 10 nodes assessed had a similar survival to patients with one positive node. The effect of the total number of assessed lymph nodes on survival has been examined in multiple studies using the SEER database.12,14,15 These studies suggest that patients should have at least 15 nodes assessed to be adequately staged which emphasizes the need for both careful surgical dissection and pathologic assessment.

The median survival of N1 patients was 16.4 months, similar to the 16 months reported by House et al.6 and 16.5 by Pawlik et al.13 A single positive lymph node was identified in 25.6% of patients, similar to the 28% reported by House et al.6 Tomlinson et al.14 identified a single positive node in 60% of the patients in the SEER database. However, the median number of assessed lymph nodes in the SEER database was only 7, a factor which could contribute to the high number of patients with a single positive node among the N1 group. In our series, patients with one positive node had a better survival when compared to patients with two positive nodes. However, the presence of more than two positive nodes was not associated with a further decrease in survival.

Recent series have emphasized the importance of the ratio of positive to total lymph nodes (LNR) as a prognostic tool in many GI cancers, including the esophagus,16 stomach,17,18 colon,19 and pancreatic adenocarcinoma.13,20,21 In our study, the median lymph node ratio was 0.2, and patients with a LNR higher than 0.2 had a significantly worse prognosis. The LNR remained highly significant on multivariate analysis. The cutoff values associated with the greatest differences in survival were 0.15 and 0.16, similar to the 0.18 value reported by House et al.6

Potential weaknesses of this study are related to its retrospective nature. Although the pathologic description of the gross specimen at our institution includes the location of the positive lymph nodes, it is possible that the rate of direct invasion is underreported. Prospectively performed studies in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma are needed to address the true rate and prognostic significance of direct lymph node invasion.

Conclusion

Isolated direct lymph node invasion by pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma occurs in at least 20% of patients with one or two positive lymph nodes. The number of positive lymph nodes, not the mechanism of lymph node involvement, is a significant predictor of overall survival. Patients with a single positive lymph node have an improved survival compared to patients with two or more positive nodes. The LNR remains a powerful prognostic tool after adjusting for other prognostic factors.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Hyacinth Haggarty and Ana Miranda from the Health Information Services and Carol Venuti from the Tumor Registry of the Massachusetts General Hospital for their precious help.

This research is being supported by the Andrew L. Warshaw, MD Institute for Pancreatic Cancer Research, Boston and by the Lantzounis research grant of the Hellenic Medical Society of New York.

Footnotes

Presented at the 50th Annual Meeting of the Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract, May 31–June 4, 2009, Chicago, IL

Contributor Information

Ioannis T. Konstantinidis, Department of Surgery, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA

Vikram Deshpande, Department of Pathology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA.

Hui Zheng, Department of Biostatistics Center, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA.

Jennifer A. Wargo, Department of Surgery, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA

Carlos Fernandez-del Castillo, Department of Surgery, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA.

Sarah P. Thayer, Department of Surgery, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA

Vasiliki Androutsopoulos, Department of Surgery, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA.

Gregory Y. Lauwers, Department of Pathology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA

Andrew L. Warshaw, Department of Surgery, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA

Cristina R. Ferrone, Email: cferrone@partners.org, Department of Surgery, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA. Wang Ambulatory Care Center 460, 15 Parkman Street, Boston, MA 02114, USA

References

- 1.American Cancer Society. www.cancer.org.

- 2.Ferrone CR, Brennan MF, Gonen M, et al. Pancreatic adenocarcinoma: the actual 5-year survivors. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12 (4):701–706. doi: 10.1007/s11605-007-0384-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Winter JM, Cameron JL, Campbell KA, et al. 1423 pancreaticoduodenectomies for pancreatic cancer: a single-institution experience. J Gastrointest Surg. 2006;10(9):1199–210. doi: 10.1016/j.gassur.2006.08.018. discussion 1210–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schnelldorfer T, Ware AL, Sarr MG, et al. Long-term survival after pancreatoduodenectomy for pancreatic adenocarcinoma: is cure possible? Ann Surg. 2008;247(3):456–462. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181613142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cleary SP, Gryfe R, Guindi M, et al. Prognostic factors in resected pancreatic adenocarcinoma: analysis of actual 5-year survivors. J Am Coll Surg. 2004;198(5):722–731. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2004.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.House MG, Gonen M, Jarnagin WR, et al. Prognostic significance of pathologic nodal status in patients with resected pancreatic cancer. J Gastrointest Surg. 2007;11(11):1549–1555. doi: 10.1007/s11605-007-0243-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lim JE, Chien MW, Earle CC. Prognostic factors following curative resection for pancreatic adenocarcinoma: a population-based, linked database analysis of 396 patients. Ann Surg. 2003;237(1):74–85. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200301000-00011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ishikawa O, Ohigashi H, Sasaki Y, et al. Practical grouping of positive lymph nodes in pancreatic head cancer treated by an extended pancreatectomy. Surgery. 1997;121(3):244–249. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6060(97)90352-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pedrazzoli S, DiCarlo V, Dionigi R, et al. Standard versus extended lymphadenectomy associated with pancreatoduodenectomy in the surgical treatment of adenocarcinoma of the head of the pancreas: a multicenter, prospective, randomized study. Lymphadenectomy Study. Group Ann Surg. 1998;228 (4):508–517. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199810000-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yeo CJ, Cameron JL, Lillemoe KD, et al. Pancreaticoduodenectomy with or without distal gastrectomy and extended retroperitoneal lymphadenectomy for periampullary adenocarcinoma, part 2: randomized controlled trial evaluating survival, morbidity, and mortality. Ann Surg. 2002;236(3):355–366. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200209000-00012. discussion 366–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Farnell MB, Pearson RK, Sarr MG, et al. A prospective randomized trial comparing standard pancreatoduodenectomy with pancreatoduodenectomy with extended lymphadenectomy in resectable pancreatic head adenocarcinoma. Surgery. 2005;138(4):618–628. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2005.06.044. discussion 628–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schwarz RE, Smith DD. Extent of lymph node retrieval and pancreatic cancer survival: information from a large US population database. Ann Surg Oncol. 2006;13(9):1189–1200. doi: 10.1245/s10434-006-9016-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pawlik TM, Gleisner AL, Cameron JL, et al. Prognostic relevance of lymph node ratio following pancreaticoduodenectomy for pancreatic cancer. Surgery. 2007;141(5):610–618. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2006.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tomlinson JS, Jain S, Bentrem DJ, et al. Accuracy of staging node-negative pancreas cancer: a potential quality measure. Arch Surg. 2007;142(8):767–723. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.142.8.767. discussion 773–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hellan M, Sun CL, Artinyan A, et al. The impact of lymph node number on survival in patients with lymph node-negative pancreatic cancer. Pancreas. 2008;37(1):19–24. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e31816074c9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wilson M, Rosato EL, Chojnacki KA, et al. Prognostic significance of lymph node metastases and ratio in esophageal cancer. J Surg Res. 2008;146(1):11–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2007.07.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Inoue K, Nakane Y, Iiyama H, et al. The superiority of ratio-based lymph node staging in gastric carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2002;9 (1):27–34. doi: 10.1245/aso.2002.9.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nitti D, Marchet A, Olivieri M, et al. Ratio between metastatic and examined lymph nodes is an independent prognostic factor after D2 resection for gastric cancer: analysis of a large European monoinstitutional experience. Ann Surg Oncol. 2003;10(9):1077–1085. doi: 10.1245/aso.2003.03.520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Le Voyer TE, Sigurdson ER, Hanlon AL, et al. Colon cancer survival is associated with increasing number of lymph nodes analyzed: a secondary survey of intergroup trial INT-0089. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(15):2912–2919. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.05.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Berger AC, Watson JC, Ross EA, Hoffman JP. The metastatic/examined lymph node ratio is an important prognostic factor after pancreaticoduodenectomy for pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Am Surg. 2004;70(3):235–240. discussion 240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smith RA, Bosonnet L, Ghaneh P, et al. Preoperative CA19–9 levels and lymph node ratio are independent predictors of survival in patients with resected pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Dig Surg. 2008;25(3):226–232. doi: 10.1159/000140961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]