Abstract

BACKGROUND

The purpose of this study was to determine whether women participating in the Women’s Healthy Eating and Living (WHEL) Study, exhibited similar dietary changes, second breast cancer events, and overall survival regardless of race/ethnicity.

METHODS

This secondary analysis used data from 3013 women self-identifying as Asian Americans, African American, Hispanic, or white and who were randomly assigned to a dietary intervention or comparison group. Changes in dietary intake over time by race/ethnicity and intervention status were examined using linear mixed-effects models. Cox proportional hazards models were used to examine the effects of the intervention on the occurrence of second breast cancer events and overall survival. Statistical tests were 2-sided.

RESULTS

African Americans and Hispanics consumed significantly more calories from fat (+3.2%) and less fruit (−0.7 servings/day) than Asians and whites at baseline (all P < 0.01). Overall, intervention participants significantly improved their dietary pattern from baseline to the end of year 1: reducing calories from fat by 4.9% and increasing intake of fiber (+6.6 grams/day), fruit (+1.1 servings/day), and vegetables (+1.6 servings/day) (all P < 0.05). Despite improvements in the overall dietary pattern of these survivors, the intervention did not significantly influence second breast cancer events and overall survival.

CONCLUSIONS

Overall, all racial groups significantly improved their dietary pattern over time, but the maintenance of these behaviors were lower among African American women. More research and larger minority samples are needed to determine the specific factors that improve breast cancer-specific outcomes in diverse populations of survivors.

Keywords: breast cancer, diet, ethnicity, race, randomized controlled trial, survival

INTRODUCTION

Systematic review studies have proposed that a healthy living for cancer survivors that includes a diet low in fat and high in fiber, fruits, and vegetables may improve health-related quality of life, prevent disease recurrence, and improve disease-specific and overall mortality.1–5 Adhering to these behaviors is especially important for minority survivors, whose risk of recurrence and comorbid conditions is greater than that of white survivors.6, 7 Therefore, interventions that promote adopting and maintaining healthy lifestyle behaviors may hold promise for improving the health and well-being of minority survivors.2, 5, 8 However, limited research exists on the health behaviors of minority survivors, and minorities are underrepresented in clinical trials promoting health behaviors.9, 10

The Women’s Healthy Eating and Living (WHEL) Study was designed to determine whether a diet low in fat and high in fruits, vegetables, and fiber could improve recurrence-free and overall survival.11 Results from the WHEL Study suggested that an intensive telephone counseling intervention could improve diet dramatically; however, this significant improvement in diet did not translate into meaningful improvements in recurrence-free and overall survival.12 On the basis of these findings, we performed a secondary analysis to determine whether the intervention resulted in similar dietary changes, regardless of race/ethnicity and whether the impact of the intervention on second breast cancer events and overall survival differed by race/ethnicity.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study Population

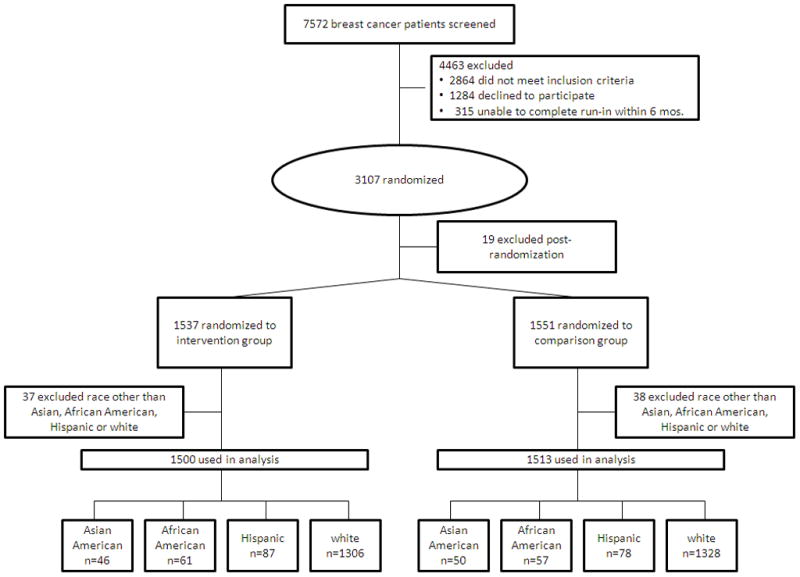

In the WHEL Study, breast cancer survivors were recruited between 1995 and 2000 from clinical sites in California, Arizona, Oregon, and Texas; the institutional review boards at all the sites approved the WHEL Study protocols. Eligible patients had been diagnosed with stage I–IIIA breast cancer within 4 years of study entry; were 18–70 years old at diagnosis; had completed treatment with no evidence of recurrent disease; and had not been diagnosed with any other cancers within 10 years of study enrollment. Additional WHEL Study inclusion and exclusion criteria have been reported previously.11 WHEL Study participants who self-reported their ethnicity as Asian American, African American, Hispanic, or white were included in the current study. The CONSORT diagram is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Consort Chart of the Women’s Healthy Eating and Living Study.

Study Design and Randomization

The WHEL Study was a multisite, randomized controlled trial designed to investigate the effects of a low-fat diet high in fiber, fruits, and vegetables on disease recurrence and overall survival in breast cancer survivors. Study participants were block-randomized to an intervention or comparison group that was stratified by clinical site, age, and tumor stage. Decisions about excluding patients from the study after randomization were made by an independent data and safety monitoring committee.11

Dietary Intervention

The daily dietary goals for the intervention group were 5 servings of vegetables, 16 ounces of vegetable juice, 3 servings of fruit, 30 grams of fiber, and 15% to 20% of energy from fat. Theory-based telephone counseling13 supplemented with 12 group cooking classes and monthly newsletters was used to deliver the intervention in 3 steps. In step 1, which included 3–8 counseling calls over 4–6 weeks, participants set short-term goals to build self-efficacy, and counselors monitored participants’ dietary behaviors. In step 2, which included 8 counseling calls over 5 months, learned to navigate barriers to and monitor their progress towards dietary goals, and counselors guided participants toward making structural changes (e.g., removing unhealthy foods from the home) and modifying recipes. In step 3, participants learned to habituate behaviors by evaluating their goals and maintaining their self-efficacy. The daily dietary goals for the comparison group consisted of 5 servings of vegetables and fruits, 20 grams of fiber, and 30% of energy from fat.14 In addition, participants in the comparison condition received 4 optional group cooking classes and dietary newsletters every other month.

Data Collection

Trained dietary assessors collected 24-hour recall data at baseline, the end of year 1, and the end of year 4. The 24-hour recalls consisted of 4 randomly selected recalls over a 3-week period for each participant. To increase the accuracy of the recalls, registered dietitians trained study participants to estimate food portion sizes. Recall data on fruits and vegetables were validated with plasma biomarkers.15 Dietary intake was estimated using the Nutritional Data System (Minneapolis, MN). In the current study, we used recall data to calculate fiber intake, servings of fruits and vegetables, and percentage of energy from fat.

Study Outcomes

The primary endpoints of the WHEL Study were breast cancer recurrence, new primary breast cancer, and death from any cause. In situ ductal or lobular carcinomas were not considered breast cancer recurrence or new primary breast cancer but were ascertained and recorded. The time to breast cancer event was defined as the time from randomization to the development of a recurrence or new primary breast cancer. Participant follow-up was censored at the time of death (if not from breast cancer), last documented staff contact date, or study completion (June 1, 2006). The endpoint was defined as death from any cause or censored at last follow-up. Each clinical site confirmed outcome events from medical records or death certificates, and an independent oncologist further confirmed each event.

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics of medical and lifestyle factors were calculated for WHEL participants in each racial group. We used 1-way analysis of variance and the chi-squared test of independence to determine whether randomization achieved balance for demographic characteristics. We also used 1-way analysis of variance to determine whether dietary outcomes (i.e., fiber intake, servings of fruits and vegetables, and percentage of energy from fat) differed between racial groups at baseline. Next, we used linear mixed-effects models to examine within-group changes in dietary intake, time-by-group interactions, and time-by-group-by-race/ethnicity interactions. The fixed effects explored in these analyses consisted of time, group, and race/ethnicity, and all combinations of the three with participants nested within study conditions were treated as random effects.

In our final series of analyses, we used adjusted Cox proportional hazards models to determine whether there were racial differences in second breast cancer events and overall survival. Similarly, we used Cox models to examine the effects of the intervention on second breast cancer events and overall survival by racial group. All data were analyzed using SAS Enterprise Guide version 4.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary NC), and significance was determined at P < 0.05 with a 2-sided test.

RESULTS

Baseline Characteristics

We identified 3013 (98%) patients in the WHEL Study who had self-reported their race/ethnicity as Asian American, African American, Hispanic, or white. Patients’ descriptive characteristics are reported in Table 1. Racial groups did not differ with regard to years since diagnosis, disease stage at diagnosis, surgery type (mastectomy or lumpectomy), or radiation treatment (all P > 0.05). However, African American and Hispanic participants were younger, had higher body mass index (BMI), and were more likely to be premenopausal at study entry than Asian Americans and whites were (all P < 0.05). African Americans were less likely to report having undergone adjuvant anti-estrogen therapy, while Asian Americans were more likely to report having undergone anti-estrogen therapy (P < 0.05). Fewer whites than women of other races received chemotherapy.

Table 1.

Baseline descriptive characteristics for Women’s Healthy Eating and Living Study participants by race.

| Variable | Asian American | African American | Hispanic | white | P value† |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 96 | n = 118 | n = 165 | n = 2634 | ||

| Median age at randomization, (25%, 75%) | 52 (47, 58) | 49 (43, 54) | 50 (44, 57) | 52 (47, 59) | <0.001 |

| Median time from diagnosis, (25%, 75%) | 2 (1, 3) | 2 (1, 3) | 2 (1, 2) | 2 (1, 3) | 0.216 |

| Median age at diagnosis, (25%, 75%) | 50 (45, 56) | 47 (42, 52) | 48 (42, 55) | 51 (45, 57) | <0.001 |

| Median body mass index, (25%, 75%) | 24.4 (22, 28) | 29.3 (26, 34) | 26.9 (24, 31) | 25.7 (23, 30) | <0.001 |

| Stage of diagnosis, n (%) | 0.308 | ||||

| I | 41 (43) | 38 (32) | 51 (31) | 1034 (39) | |

| IIA | 28 (29) | 44 (37) | 71 (43) | 861 (33) | |

| IIB | 12 (13) | 18 (15) | 15 (9) | 322 (12) | |

| IIIA | 12 (13) | 15 (13) | 20 (12) | 319 (12) | |

| IIIC | 3 (3) | 3 (3) | 8 (5) | 98 (4) | |

| Treatment, n (%) | |||||

| Mastectomy/Lumpectomy | 55 (57) | 59 (50) | 87 (53) | 1366 (52) | 0.725 |

| Radiation | 56 (59) | 79 (67) | 103 (62) | 1622 (62) | 0.639 |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | 73 (76) | 91 (77) | 129 (78) | 1814 (69) | 0.010 |

| Anti-estrogen therapy | 75 (78) | 68 (56) | 108 (65) | 1807 (69) | 0.011 |

| % Premenopausal | 9 (9) | 22 (19) | 25 (15) | 286 (11) | 0.020 |

Note: All data are no. of patients (%) unless otherwise indicated.

Compares descriptive characteristics between racial groups. Continuous P-values are base on nonparametric Kruskall Wallis test, whereas categorical P-values are based on chi-square test for independence.

The intervention and comparison groups did not differ with regard to years since diagnosis, disease stage at diagnosis, mastectomy, and adjuvant chemotherapy (all P > 0.05). Among Asian Americans, mean BMI was higher in the intervention group (25.6 kg/m2) than in the comparison group (23.9 kg/m2, P < 0.05). Among African Americans, mean BMI was higher in the comparison group (32.4 kg/m2) than in the intervention group (29.5 kg/m2, P < 0.05). Among Hispanics, participants in the intervention group were younger at diagnosis (46.6 years vs. 50.2 years), younger at study entry (48.9 years vs. 52.5 years), less likely to have undergone radiation treatment (54% vs. 72%), and more likely to be premenopausal (21% vs. 9%) (all P < 0.05). Among whites, intervention participants were more likely to have undergone adjuvant anti-estrogen therapy (71% vs. 66%, P < 0.05). Other factors, including tumor characteristics (i.e., grade, nodal status, and hormone-receptor status) and breast-sparing surgery were not different among races or between intervention and comparison groups (data not shown; all P > 0.05).

Dietary intake at baseline

Table 2 contains information about dietary patterns at baseline and changes in dietary patterns between baseline and the end of year 4. At baseline, African American and Hispanic participants received a significantly higher percentage of total energy from fat and consumed fewer daily servings of fruits and vegetables than Asian American and white participants (all P < 0.01). In addition, African American survivors consumed significantly less fiber than Asian American, Hispanic, and white survivors (P < 0.01), whereas Hispanic survivors consumed significantly less fiber than white survivors (P < 0.05) but not less fiber than African American or Asian American participants (Table 2).

Table 2.

Dietary factors for selected change at baseline and over time by study condition and racial group

| Ethnic group and P value | Calories from fat, % | Fiber, g/day | Fruit servings/day | Vegetable servings/day | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean at baseline (SD) | Mean change at 1 year | Mean change at 4 years | Mean at baseline (SD) | Mean change at 1 year | Mean change at 4 years | Mean at baseline (SD) | Mean change at 1 year | Mean change at 4 years | Mean at baseline (SD) | Mean change at 1 year | Mean change at 4 years | |

| Race P value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||||||||

| Asian American | ||||||||||||

| Intervention group | 27.2 (7.2) | −4.2† | −0.7 | 19.8 (7.0) | 8.0‡ | 6.4† | 2.6 (1.6) | 1.0† | 0.8* | 3.0 (1.8) | 2.1‡ | 2.0‡ |

| Comparison group | 27.4 (6.8) | 0.2 | 2.8* | 20.1 (6.8) | −1.0 | −1.6 | 2.7 (1.8) | −0.1 | −0.2 | 3.4 (2.1) | −0.3 | −0.6 |

| Time-group P value | 0.005 | 0.038 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 0.017 | 0.024 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||||

| African American | ||||||||||||

| Intervention group | 29.6 (6.1) | −4.0† | −0.1 | 16.9 (6.8) | 5.5‡ | 2.6 | 1.8 (1.5) | 1.1† | 0.8* | 2.4 (1.2) | 1.2‡ | 0.7* |

| Comparison group | 32.7 (6.0) | −1.5 | 0.4 | 15.9 (6.7) | −1.0 | −0.8 | 1.7 (1.7) | −0.1 | −0.5 | 2.1 (1.4) | −0.2 | 0.4 |

| Time-group P value | 0.184 | 0.779 | < 0.001 | < 0.024 | 0.006 | 0.005 | < 0.001 | 0.472 | ||||

| Hispanic | ||||||||||||

| Intervention group | 30.4 (6.9) | −5.7‡ | −1.4 | 19.7 (6.5) | 5.0‡ | 2.7* | 1.9 (1.4) | 1.1‡ | 0.8† | 2.7 (1.6) | 1.4‡ | 0.8‡ |

| Comparison group | 30.2 (6.8) | −0.7 | 1.4 | 19.6 (7.7) | −0.1 | −3.0† | 2.0 (1.5) | 0.3 | −0.0 | 2.4 (1.6) | 0.0 | −0.4 |

| Time-group P value | < 0.001 | 0.020 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 0.010 | 0.019 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||||

| white | ||||||||||||

| Intervention group | 28.5 (7.2) | −5.8‡ | −1.2‡ | 21.4 (8.4) | 7.8‡ | 3.7‡ | 2.5 (1.8) | 1.0‡ | 0.5‡ | 2.9 (1.7) | 1.7‡ | 1.3‡ |

| Comparison group | 28.4 (7.0) | −0.2 | 3.0‡ | 21.5 (8.1) | −0.2 | −2.1‡ | 2.4 (1.7) | 0.1* | −0.3‡ | 2.9 (1.7) | 0.1* | 0.0 |

| Time-group P value | < 0.001 | <0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||||

| Time-group-race | ||||||||||||

| P value | 0.134 | 0.169 | 0.164 | 0.442 | 0.806 | 0.670 | 0.169 | 0.002 | ||||

Note: Estimates of change are expressed for within-group differences from baseline to the indicated time point. Race P values represent baseline differences between racial groups among dietary components. Time-group P values represent time-by-group interactions comparing the degree of change from baseline to the indicated time point between study conditions. Time-group-race P values represent time-by-group-by-race interactions comparing the degree of change from baseline to the indicated time points among racial groups and between study conditions.

SD = standard deviation.

Significance at P < .05.

Significance at P < .01.

Significance at P < .001.

Dietary Pattern over 4 Years

The intervention group as a whole exhibited significant improvements in fiber intake, servings of fruits and vegetables, and the percentage of energy from fat from baseline to the end of year 1 (all P < 0.01). Participants in the comparison group did not significantly change their diet, except for minimal improvements in servings of fruits and vegetables among white participants (both P < 0.05). For all ethnic groups, differences in dietary changes between the intervention and comparison arms translated into significant time-by-group interactions for fiber intake and servings of fruits and vegetables (all P < 0.05). In addition, significant time-by-group interactions were observed for the percentage of energy from fat for Asian American, Hispanic, and white participants (all P < 0.01), but not for African American participants (P = 0.184). Despite these differences between racial groups, none of the group-by-time-by-race/ethnicity interactions for the change between baseline and the end of year 1 were significant.

Survivors in the intervention group, regardless of race/ethnicity, exhibited modest regression to the mean from the end of year 1 to the end of year 4 but significant improvement in servings of fruits and vegetables from baseline to the end of year 4 (all P < 0.05). In addition, Asian American, Hispanic, and white participants had significant improvement in fiber intake from baseline to the end of year 4 (all P < 0.05); however, only white participants had significant improvement in the percentage of energy from fat (P < 0.001). Significant time-by-group interactions for fiber intake and servings of fruits were observed in all racial groups in the intervention arm, whereas only Asian American, Hispanic, and white participants exhibited significant time-by-group interactions for servings of vegetables and percentage of calories from fat from baseline to the end of year 4 (all P < 0.05). The group-by-time-by-ethnicity interaction from baseline to the end of year 4 was significant (P < 0.01) only for servings of vegetables. These data suggested that the amount of change from baseline to the end of year 4 between the intervention and comparison groups was greater for white and Asian American participants than for African American and Hispanic participants (P < 0.01).

Recurrence and Mortality

Hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for breast cancer recurrence and overall survival rates are reported in Table 3. Breast cancer recurrence rates over a median follow-up of 7.3 years were similar among white (16.7%), African American, (18.6%), and Hispanic survivors (17.6%). However, Asian survivors had a significantly lower breast cancer recurrence rate than white survivors (9.4% event rate; adjusted HR = 0.50; 95% CI = 0.26, 0.97; P = 0.04). Mortality rates did not differ significantly among ethnicities.

Table 3.

Cox proportional hazard ratios for recurrence and mortality

| Race | No. of participants | Participants whose disease recurred, % | Breast cancer recurrence HR (95% CI) | P value | Participant deaths, % | Mortality, HR (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asian | 96 | 9.4 | 0.50 (0.26 – 0.97) | 0.040 | 8.3 | 0.86 (0.43 – 1.75) | 0.686 |

| African-American | 118 | 18.6 | 1.08 (0.70 – 1.66) | 0.733 | 13.6 | 1.28 (0.77 – 2.14) | 0.343 |

| Hispanic | 165 | 17.6 | 1.00 (0.69 – 1.46) | 0.992 | 10.9 | 0.98 (0.61 – 1.59) | 0.948 |

| white | 2634 | 16.7 | −1- | Referent | 9.9 | −1- | Referent |

Note: All models were adjusted for tumor stage, grade, and body mass index.

HR = hazard ratio; CI = confidence interval.

Survivors were followed for a mean of 7.3 years.

The intervention effects are reported in Table 4. Overall, the WHEL Study intervention did not significantly impact breast cancer recurrence or overall survival rates for any racial group (Table 4), even after adjustment for age, radiation therapy, anti-estrogen therapy, and/or BMI.

Table 4.

Cox proportional hazard ratios modeling the Women’s Healthy Eating and Living Study intervention effects on recurrence free and overall survival by ethnicity

| Race | No. of participants in the intervention group whose disease recurred | No. of participants in the comparison group whose disease recurred | Breast cancer events, HR (95% CI) | P value | No. of deaths in the intervention group | No. of deaths in the comparison group | Mortality, HR (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asian* | 6/46 | 3/50 | 2.09 (0.52 – 8.49) | 0.300 | 4/46 | 4/50 | 0.85 (0.20 – 3.50) | 0.819 |

| African-American* | 14/61 | 8/57 | 1.61 (0.67 – 3.87) | 0.288 | 10/61 | 6/57 | 1.45 (0.52 – 4.03) | 0.477 |

| Hispanic† | 13/87 | 16/78 | 0.67 (0.31 – 1.43) | 0.362 | 8/87 | 10/78 | 0.70 (0.26 – 1.87) | 0.479 |

| white‡ | 216/1306 | 223/1328 | 0.98 (0.82 – 1.19) | 0.864 | 127/1306 | 133/1328 | 0.98 (0.77 – 1.30) | 0.868 |

Note: Adjustments were made based on baseline differences between intervention and comparison conditions.

HR = hazard ratio; CI = confidence interval.

Survivors were followed for a mean of 7.3 years

Models were adjusted for baseline body mass index.

Models were adjusted for age at study entry, age at diagnosis, radiation treatment and menopausal status.

Models were adjusted for anti-estrogen use.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we found that regardless of race, participants randomized to the WHEL Study intervention group consumed significantly less dietary fat and significantly more fiber, fruits, and vegetables than participants randomized to the comparison group at the end of year 1. Participants in the intervention group also maintained improvements in fruit and vegetable consumption through the end of year 4. Although the dietary patterns improved significantly for all racial groups randomized to the intervention, none of the ethnic groups experienced reductions in breast cancer recurrence rates or improvements in overall survival. This secondary analysis of the WHEL Study confirmed the findings of previous analyses regarding dietary change achieved in the WHEL Study12 and provides insight with respect to the effectiveness of a dietary intervention for minority cancer survivors.

Our secondary analysis of data from the WHEL Study, which was one of the first randomized trials to report on the dietary habits of minority cancer survivors, revealed that many breast cancer survivors do not meet the American Cancer Society’s dietary guidelines.5 In addition, we observed that the dietary habits of African American and Hispanic survivors at baseline were worse than those reported by whites and Asian Americans. The racial differences in dietary intake among minorities at baseline may be due to social and cultural barriers such as differential body-image ideals (e.g., big is beautiful) and cultural food attitudes.16 Overcoming these cultural impediments may require developing new support networks that encourage and/or support positive health behaviors.17 In a recent study among African American breast cancer survivors,18 an intervention designed to build support by incorporating family and friends resulted in significant weight loss, dietary fat reduction, and increased fiber consumption. Therefore, interventions designed for minority survivors may be improved by incorporating the social network of the survivor.

The WHEL Study intervention was associated with substantial improvements in dietary intake among all survivors, regardless of race. The increases in fruit and vegetable intake exceeded those reported in previous intervention studies,19–23 and these improvements were maintained at the 4-year follow-up. However, African American participants did not maintain improvements in fiber intake at the 4-year follow-up, and no racial group maintained meaningful improvements in dietary fat intake. Why survivors were unable to maintain improvements in dietary fat and fiber intake is unclear, therefore, alternative strategies, such as tailoring the dietary intervention to individual survivors’ needs, are needed to maintain improvements in these behaviors as survivors move further from the intensive phases of the intervention.24 Such strategies may be particularly beneficial for African American and Hispanic participants, because the magnitude of change in diet among these participants was not as great as that observed among Asian and white participants.

African American and Hispanic survivors did not differ from white survivors in the number of second breast cancer events or overall survival despite baseline differences in dietary intake. This result differs from population-based statistics,6, 7 which suggest that African American and Hispanic women have higher recurrence and mortality rates than white women. In fact, Asian Americans experienced lower recurrence rates than whites. Lower weight among Asian American women could have contributed to these differences, and if so, would confirm the results of previous studies suggesting that weight status may be an immediate causal factor in poor prognostic outcomes.25, 26 Therefore, regardless of race, women should consider adhering to the American Cancer Society’s guidelines5 for maintaining a healthy weight in an effort to reduce the odds of poor breast cancer-related outcomes.

Despite the success of the telephone counseling,27–30 the WHEL Study intervention did not improve breast cancer recurrence or overall survival rates among minority breast cancer survivors. However, we know from healthy populations that a dietary pattern low in fat and high in fruits, vegetables, and fiber may reduce the risk of most chronic diseases.31, 32 Therefore, it is possible that survivors participating in the WHEL Study intervention may experience improvements in outcomes that extend beyond the study’s completion date and that may be explored in future analyses of these data.

The results among our minority subgroups are similar to those reported in the primary analysis12 but differ from those of interim analyses from the Women’s Intervention Nutrition Study,33 which found that a significant reduction in dietary fat was associated with 24% improvements in recurrence rates. The WHEL Study intervention may be beneficial for certain subgroups, as implied by the results observed among women who did not report hot flashes at baseline.27, 34, 35 However, more research and larger minority samples than available in the WHEL Study are needed to determine whether subgroup benefits are generalizable to minority breast cancer survivors.

The current study was not without potential limitations. For example, most of the patients in the current study had a high level of education and already had dietary patterns that closely reflected the guidelines recommended by the American Cancer Society. Therefore, the results of the current study may not be generalizable to all populations of breast cancer survivors. In addition, our multiple 24-hour dietary recalls for each participant were self-reported; thus, the study had the potential for inaccurate recall and reporting biases. Furthermore, this study was not powered to examine race/ethnicity differences and survivors were only followed for a median of 7.3 years. This length of time may not be long enough to see the effects of a dietary intervention in relatively healthy sample of breast cancer survivors. Despite its potential limitations, the current study had a number of notable strengths, including a randomized design, which eliminated selection bias; 24-hour recall data on fruit and vegetable intake, which was significantly correlated with plasma carotenoid levels;36, 37 inclusion of premenopausal and postmenopausal women; and inclusion of women with aggressive tumors.38

In conclusion, this secondary analysis demonstrated that the WHEL Study intervention was effective in changing dietary intake in all survivors, regardless of race; however, African American women were less likely to maintain these improvements over time. In addition, lower breast cancer recurrence rates observed among Asian women may suggest that we should look to this group as a model for healthy behaviors. That said, more research is needed to identify lifestyle factors that reduce rates of breast cancer recurrence and mortality and improve health-related quality of life. Furthermore, there is a need for more research powered to examine racial differences in the context of long-term lifestyle interventions.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This research was supported in part by a Cancer Prevention Fellowship supported by National Cancer Institute grants CA57730 and CA69375 and by the National Institutes of Health through MD Anderson’s Cancer Center Support Grant CA016672.

The authors thank the Women’s Healthy Eating and Living Study Group, who were involved in patient recruitment, dietary intervention, and data collection, and the staff and participants of the Women’s Healthy Eating and Living Study.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no financial conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.World Cancer Research Fund. American Institute for Cancer Research expert report: Food, Nutrition, Physical Activity, and the Prevention of cancer: a global perspective. Washington, DC: American Institute for Cancer Research; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barrera S, Demark-Wahnefried W. Nutrition during and after cancer therapy. Oncology (Williston Park) 2009;23(2 Suppl Nurse Ed):15–21. Available from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=19856583. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Demark-Wahnefried W, Jones LW. Promoting a healthy lifestyle among cancer survivors. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2008;22(2):319–42. viii. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2008.01.012. Available from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=18395153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Demark-Wahnefried W, Rock CL, Patrick K, Byers T. Lifestyle interventions to reduce cancer risk and improve outcomes. Am Fam Physician. 2008;77(11):1573–8. Available from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=18581838. [PubMed]

- 5.Doyle C, Kushi LH, Byers T, Courneya KS, Demark-Wahnefried W, Grant B, et al. Nutrition and physical activity during and after cancer treatment: an American Cancer Society guide for informed choices. CA Cancer J Clin. 2006;56(6):323–53. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.56.6.323. Available from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=17135691. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Cancer Facts & Figures for Hispanics/Latinos 2009–2011. Vol. 2004. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cancer Facts & Figures for African Americans 2009–2010. Vol. 2004. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Demark-Wahnefried W, Aziz NM, Rowland JH, Pinto BM. Riding the crest of the teachable moment: promoting long-term health after the diagnosis of cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(24):5814–30. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.230. Available from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=16043830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Linden HM, Reisch LM, Hart A, Jr, Harrington MA, Nakano C, Jackson JC, et al. Attitudes toward participation in breast cancer randomized clinical trials in the African American community: a focus group study. Cancer Nurs. 2007;30(4):261–9. doi: 10.1097/01.NCC.0000281732.02738.31. Available from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=17666974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Sears SR, Stanton AL, Kwan L, Krupnick JL, Rowland JH, Meyerowitz BE, et al. Recruitment and retention challenges in breast cancer survivorship research: results from a multisite, randomized intervention trial in women with early stage breast cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2003;12(10):1087–90. Available from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=14578147. [PubMed]

- 11.Pierce JP, Faerber S, Wright FA, Rock CL, Newman V, Flatt SW, et al. A randomized trial of the effect of a plant-based dietary pattern on additional breast cancer events and survival: the Women’s Healthy Eating and Living (WHEL) Study. Control Clin Trials. 2002;23(6):728–56. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(02)00241-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pierce JP, Natarajan L, Caan BJ, Parker BA, Greenberg ER, Flatt SW, et al. Influence of a diet very high in vegetables, fruit, and fiber and low in fat on prognosis following treatment for breast cancer: the Women’s Healthy Eating and Living (WHEL) randomized trial. JAMA. 2007;298(3):289–98. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.3.289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bandura A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev. 1977;84(2):191–215. doi: 10.1037//0033-295x.84.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.USDA/DHHS. Dietary guideline for Americans. Department of Health and Human Services; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pierce JP, Natarajan L, Sun S, Al-Delaimy W, Flatt SW, Kealey S, et al. Increases in plasma carotenoid concentrations in response to a major dietary change in the women’s healthy eating and living study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15(10):1886–92. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kumanyika S. The minority factor in the obesity epidemic. Ethn Dis. 2002;12(3):316–9. Available from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=12148700. [PubMed]

- 17.Gaston MH, Porter GK, Thomas VG. Prime Time Sister Circles: evaluating a gender-specific, culturally relevant health intervention to decrease major risk factors in mid-life African-American women. J Natl Med Assoc. 2007;99(4):428–38. Available from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=17444433. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Stolley MR, Sharp LK, Oh A, Schiffer L. A weight loss intervention for African American breast cancer survivors, 2006. Prev Chronic Dis. 2009;6(1):A22. Available from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=19080028. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Caan B, Sternfeld B, Gunderson E, Coates A, Quesenberry C, Slattery ML. Life After Cancer Epidemiology (LACE) Study: a cohort of early stage breast cancer survivors (United States) Cancer Causes Control. 2005;16(5):545–56. doi: 10.1007/s10552-004-8340-3. Available from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=15986109. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Demark-Wahnefried W, Clipp EC, Lipkus IM, Lobach D, Snyder DC, Sloane R, et al. Main outcomes of the FRESH START trial: a sequentially tailored, diet and exercise mailed print intervention among breast and prostate cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(19):2709–18. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.10.7094. Available from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=17602076. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Demark-Wahnefried W, Clipp EC, Morey MC, Pieper CF, Sloane R, Snyder DC, et al. Lifestyle intervention development study to improve physical function in older adults with cancer: outcomes from Project LEAD. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(21):3465–73. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.05.7224. Available from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=16849763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Morey MC, Snyder DC, Sloane R, Cohen HJ, Peterson B, Hartman TJ, et al. Effects of home-based diet and exercise on functional outcomes among older, overweight long-term cancer survivors: RENEW: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;301(18):1883–91. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.643. Available from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=19436015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Wayne SJ, Lopez ST, Butler LM, Baumgartner KB, Baumgartner RN, Ballard-Barbash R. Changes in dietary intake after diagnosis of breast cancer. J Am Diet Assoc. 2004;104(10):1561–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2004.07.028. Available from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=15389414. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Curtis L, Brown ZG, Gill JE. Sisters Together: Move More, Eat Better: a community-based health awareness program for African-American women. J Natl Black Nurses Assoc. 2008;19(2):59–64. Available from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=19397055. [PubMed]

- 25.Nichols HB, Trentham-Dietz A, Egan KM, Titus-Ernstoff L, Holmes MD, Bersch AJ, et al. Body mass index before and after breast cancer diagnosis: associations with all-cause, breast cancer, and cardiovascular disease mortality. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18(5):1403–9. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-1094. Available from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=19366908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Petrelli JM, Calle EE, Rodriguez C, Thun MJ. Body mass index, height, and postmenopausal breast cancer mortality in a prospective cohort of US women. Cancer Causes Control. 2002;13(4):325–32. doi: 10.1023/a:1015288615472. Available from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=12074502. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Gold EB, Pierce JP, Natarajan L, Stefanick ML, Laughlin GA, Caan BJ, et al. Dietary pattern influences breast cancer prognosis in women without hot flashes: the women’s healthy eating and living trial. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(3):352–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.1067. Available from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=19075284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Madlensky L, Natarajan L, Flatt SW, Faerber S, Newman VA, Pierce JP. Timing of dietary change in response to a telephone counseling intervention: evidence from the WHEL study. Health Psychol. 2008;27(5):539–47. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.27.5.539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pierce JP, Newman VA, Flatt SW, Faerber S, Rock CL, Natarajan L, et al. Telephone counseling intervention increases intakes of micronutrient- and phytochemical-rich vegetables, fruit and fiber in breast cancer survivors. J Nutr. 2004;134(2):452–8. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.2.452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pierce JP, Newman VA, Natarajan L, Flatt SW, Al-Delaimy WK, Caan BJ, et al. Telephone counseling helps maintain long-term adherence to a high-vegetable dietary pattern. J Nutr. 2007;137(10):2291–6. doi: 10.1093/jn/137.10.2291. Available from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=17885013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Kushi LH, Byers T, Doyle C, Bandera EV, McCullough M, McTiernan A, et al. American Cancer Society Guidelines on Nutrition and Physical Activity for cancer prevention: reducing the risk of cancer with healthy food choices and physical activity. CA Cancer J Clin. 2006;56(5):254–81. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.56.5.254. quiz 313–4. Available from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=17005596. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Kahn R, Robertson RM, Smith R, Eddy D. The impact of prevention on reducing the burden of cardiovascular disease. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(8):1686–96. doi: 10.2337/dc08-9022. Available from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=18663233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Chlebowski RT, Blackburn GL, Thomson CA, Nixon DW, Shapiro A, Hoy MK, et al. Dietary fat reduction and breast cancer outcome: interim efficacy results from the Women’s Intervention Nutrition Study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98(24):1767–76. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj494. Available from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=17179478. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Pierce JP, Natarajan L, Caan BJ, Flatt SW, Kealey S, Gold EB, et al. Dietary change and reduced breast cancer events among women without hot flashes after treatment of early-stage breast cancer: subgroup analysis of the Women’s Healthy Eating and Living Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;89(5):1565S–71S. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.26736F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thomson CA, Rock CL, Thompson PA, Caan BJ, Cussler E, Flatt SW, et al. Vegetable intake is associated with reduced breast cancer recurrence in tamoxifen users: a secondary analysis from the Women’s Healthy Eating and Living Study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010 doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-1014-9. in press. Available from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=20607600. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Natarajan L, Flatt SW, Sun X, Gamst AC, Major JM, Rock CL, et al. Validity and systematic error in measuring carotenoid consumption with dietary self-report instruments. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;163(8):770–8. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj082. Available from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=16524958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Thomson CA, Giuliano A, Rock CL, Ritenbaugh CK, Flatt SW, Faerber S, et al. Measuring dietary change in a diet intervention trial: comparing food frequency questionnaire and dietary recalls. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157(8):754–62. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg025. Available from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=12697580. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Pierce JP. Diet and breast cancer prognosis: making sense of the Women’s Healthy Eating and Living and Women’s Intervention Nutrition Study trials. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2009;21(1):86–91. doi: 10.1097/gco.0b013e32831da7f2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]