Abstract

Crude extract of Myrica esculenta fruits, a wild edible species of Indian Himalayan Region, was evaluated for phenolic compounds and antioxidant properties. Results revealed significant variation in total phenolic and flavonoid contents across populations. Among populations, total phenolic content varied between 1.78 and 2.51 mg gallic acid equivalent/g fresh weight (fw) of fruits and total flavonoids ranged between 1.31 and 1.59 mg quercetin equivalent/g fw. Antioxidant activity determined by 2,2′-azinobis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulphonic acid) radical scavenging, 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl radical scavenging and ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP) exhibited considerable antioxidant potential and showed significant positive correlation with total phenolic and total flavonoids content. High performance liquid chromatography analysis revealed significant variation (P < .01) in phenolic compounds (i.e., gallic acid, catechin, hydroxybenzioc acid and ρ-coumaric acid) across populations. This study provides evidences to establish that consumption of M. esculenta fruits while providing relished taste would also help in reduction of free radicals. Therefore, this wild edible species deserves promotion in the region through horticulture and forestry interventions.

1. Introduction

Consumption of fruits and vegetables is known to lower risk of several oxidative stresses, including cardiovascular diseases, cancer and stroke [1] and such health benefits are mainly ascribed to phytochemicals such as polyphenols, carotenoids and vitamin C [2]. Of these phytochemicals, polyphenols are largely recognized as anti-inflammatory, antiviral, antimicrobial and antioxidant agents [3].

Considering above facts, besides the traditional commercial fruits, the wild fruits are also gaining increased attention as potential food supplement or cheaper alternative of commercial fruits across the world. Evidences of the health benefits of wild edible fruits, in addition to established role in nutrition are available [4]. In general, plethora of information is available on the antioxidant potential of fruits of different species. For example, Actinidia eriantha, A. deliciosa [5], Ficus carica [6], Ficus microcarpa [7], Ficus racemosa [8], Juglans regia [9], Kadsura coccinea [10], Litchi chinensis [11], Morus alba [12], Myrciaria dubia [13], Nocciola piemonte [14], Phyllanthus emblica [15], Punica granatum [16], Randia echinocarpa [17], Ziziphus mauritiana [18] and so forth. Beside the fruits, antioxidant properties are also known for other plant parts [19, 20].

In the Indian Himalayan Region (IHR) over 675 wild edibles are known [21] of which Myrica esculenta Buch.–Ham. ex D. Don (family Myricaceae), commonly known as “Kaphal", is amongst highly valued wild edible fruits growing between 900 and 2100 m above sea level (asl). Species is distributed from Ravi eastward to Assam, Khasi, Jaintia, Naga and Lushi hills and extends to Malaya, Singapore, China and Japan [22]. It is popular among local inhabitants for its delicious fruits and processed products [23]. This species broadly resembles with Myrica rubra, found commonly in China and Japan. However, M. esculenta contains smaller fruits of around 4-5 mm as compared with 12–15 mm fruits of M. rubra [24]. While information is available on phenolic contents, flavonoids, anthocyanins and antioxidant activity of M. rubra fruit extract, juice, jam and pomace [25–29], such information is lacking for M. esculenta. This study, therefore, targets M. esculenta fruits for assessment of total phenolics, flavonoids and phenolic compounds; evaluate range of variation in antioxidant activity using different in vitro methods and identify the best fruit provenance.

2. Methods

2.1. Plant Material

The ripened fruits of M. esculenta were collected during May–June 2008, from distantly located wild populations (i.e., Kalika (1775), Ayarpani (1950), Panuwanaula (1800), Jalna (1925), Dholichina (1950), Khirshu (1650), Shyamkhet (1975), Gwaldom (1925) and Doonagiri (2100 m asl)) in Uttarakhand, India. Immediately after collection, fruits were brought to the laboratory and kept in freezer at –4°C. The voucher specimens of the species were deposited in the herbarium of G. B. Pant Institute of Himalayan Environment and Development, Kosi-Katarmal, Almora.

2.2. Chemicals and Reagents

1,1-Diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) radical, gallic acid, ascorbic acid, chlorogenic acid, caffeic acid, ρ-coumaric acid, 3-hydroxybenzoic acid, catechin and quercetin were procured from Sigma-Aldrich (Steinheim, Germany). Sodium carbonate, 2-(n-morpholino) ethanesulfonic acid (MES buffer), potassium persulphate, ferric chloride, sodium acetate, potassium acetate, aluminium chloride, glacial acetic acid and hydrochloric acid from Qualigens (Mumbai, India), and 2,2′-azinobis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulphonic acid) (ABTS), 2,4,6-tri-2-pyridyl-1,3,5-triazin (TPTZ), methanol and ethanol from Merck Company (Darmstadt, Germany).

2.3. Extract Preparation for Total Phenolics, Flavonoids and Antioxidant Properties

Fresh fruits (20 g) from each population were used for preparation of extract. Pulp of the fruits was carefully removed from seed and kept for continuous stirring with 50 mL (80% v/v) methanol for 24 h. Extract was filtered and filtrate was centrifuged at 8000 rpm for 10 min. Supernatant was stored at 4°C prior to use within 2 days.

2.4. Determination of Total Phenolics

Total phenolic content in the methanolic extract was determined by Folin-Ciocalteu's calorimetric method [30]. In 0.25 mL of diluted methanolic extract, 2.25 mL distilled water and 0.25 mL Folin-Ciocalteu's reagent was added and allowed to stand for reaction upto 5 min. This mixture was neutralized by 2.50 mL of 7% sodium carbonate (w/v) and kept in dark at room temperature for 90 min. The absorbance of resulting blue color was measured at 765 nm using UV-VIS spectrophotometer (Hitachi U-2001). Quantification was done on the basis of standard curve of gallic acid prepared in 80% methanol (v/v) and results were expressed in milligrams gallic acid equivalent (GAE) per gram fresh weight (fw) of fruits.

2.5. Determination of Total Flavonoids

Flavonoid content in the methanolic extract of plant was determined by aluminium chloride calorimetric method [31]. Briefly, 0.50 mL of methanolic extract of sample was diluted with 1.50 mL of distilled water and 0.50 mL of 10% (w/v) aluminium chloride added along with 0.10 mL of 1 M potassium acetate and 2.80 mL of distilled water. This mixture was incubated at room temperature for 30 min. The absorbance of resulting reaction mixture was measured at 415 nm UV-VIS spectrophotometer (Hitachi U-2001). Quantification of flavonoids was done on the basis of standard curve of quercetin prepared in 80% methanol and results were expressed in milligram quercetin equivalent (QE) per gram fw of fruits.

2.6. Antioxidant Activity

2.6.1. Radical Scavenging Activity (ABTS Assay)

Total antioxidant activity was measured by improved ABTS method described by Cai et al. [32]. ABTS salt (7.0 μM) and potassium persulfate (2.45 μM) was added for the production of ABTS cation (ABTS·+) and kept in dark for 16 h at 23°C. ABTS·+ solution was diluted with 80% (v/v) ethanol till an absorbance of 0.700 ± 0.005 at 734 nm was obtained. Diluted ABTS·+ solution (3.90 mL) was added in 0.10 mL of methanolic extract and the resulting mixture was mixed thoroughly. Reaction mixture was allowed to stand for 6 min in dark at 23°C and absorbance was recorded at 734 nm using UV-VIS spectrophotometer. Samples were diluted with 80% (v/v) methanol to obtain 20–80% reduction in absorbance at 734 nm with respect to blank that was prepared with 0.10 mL 80% (v/v) methanol. A standard curve of various concentrations of ascorbic acid was prepared in 80% v/v methanol for the equivalent quantification of antioxidant potential with respect to ascorbic acid. Results were expressed in millimole (mM) ascorbic acid equivalent (AAE) per 100 g fw of fruits.

2.6.2. Radical Scavenging Activity (DPPH Assay)

Traditional DPPH assay as described by Brand-William et al. [33] was modified for this study. An amount of 25 mL of 400 mM DPPH was added in 25 mL of 0.2 M MES buffer (pH 6.0 adjusted with NaOH) and 25 mL 20% (v/v) ethanol. DPPH cation solution (2.7 mL) was mixed with 0.9 mL sample extract and kept in dark at room temperature for 20 min. Reduction in the absorbance at 520 nm was recorded by UV-VIS spectrophotometer. Results were expressed in millimole (mM) ascorbic acid equivalent (AAE) per 100 g fw of fruits.

2.6.3. Reducing Power (FRAP) Assay

Ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP) assay was performed following Benzie and Strain [34] with some modifications. FRAP reagent was prepared by adding 10 vol. of 300 mM acetate buffer (i.e., 3.1 g of sodium acetate and 16 mL glacial acetic acid per liter), 1 vol. of 10 mM 2,4,6-tri-2-pyridyl-1,3,5-triazin (TPTZ) in 40 mM HCl and 1 vol. of 20 mM ferric chloride. The mixture was pre-warmed at 37°C and 3.0 mL of the mixture was added to 0.10 mL methanolic extract and kept at 37°C for 8 min. Absorbance was taken at 593 nm by UV-VIS spectrophotometer. A blank was prepared by ascorbic acid and results were expressed in millimole (mM) of ascorbic acid equivalent (AAE) per 100 g fw of fruits.

2.7. HPLC Analysis of Phenolic Compounds

One hundred and twenty microliters extract of each population was used in triplicate in high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) system equipped with L-7100 series pump (Merck-Hitachi, Japan) and L-7400 series UV-VIS detector (Merck-Hitachi, Japan). Phenolic compounds were separated by using 4.6 × 250 mm i.d., 5 μm, Purosphere; C8 column. The mobile phase used for the study was water, methanol and acetic acid in the ratio of 80 : 20 : 1 and flow rate was 0.8 mL/min in isocratic mode. The spectra of compounds (total seven) were recorded at 254 nm for gallic acid, catechin, ellagic acid and 3-hydroxybenzoic acid, 370 nm for caffeic acid and chlorogenic acid and 280 nm for ρ-coumaric acid. The identification of phenolic compounds was done with respect of the retention time of corresponding external standard. UV-VIS spectra of pure standard at different concentrations were used for plotting standard calibration curve. The repeatability of quantitative analysis was 3.5%. The mean value of content was calculated with ±SD. The result was expressed as milligram per 100 g fw of fruits.

2.8. Statistical Analysis

All determinations of total phenols, flavonoids, antioxidant capacity by ABTS, DPPH, FRAP assay were conducted in five replicates. Phenolic compounds were measured in triplicates. The value for each sample was calculated as the mean ± SD. Analysis of variance and significant difference among means were tested by two way ANOVA using SPSS and Fisher's least significance difference (F-LSD) on mean values [35]. Correlation coefficients (r) and coefficients of determination (r 2) were calculated using Microsoft Excel 2007.

3. Results

3.1. Total Phenolic and Flavonoid Content

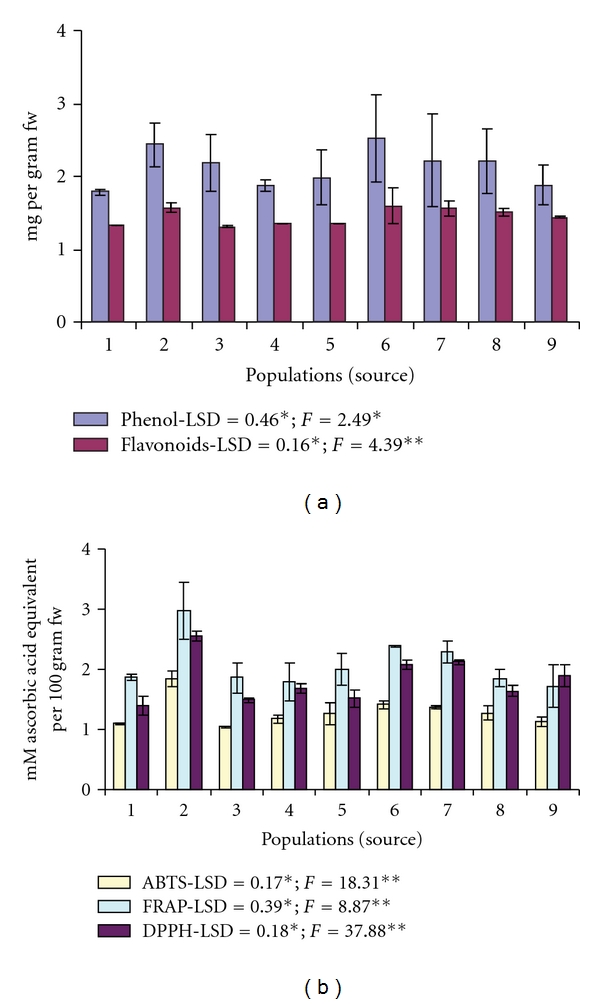

Total phenolic content in fruit extracts of M. esculenta varied between 1.78 mg GAE/gram (Kalika) and 2.51 mg GAE/gram fw (Khirshu) with an average value of 2.12 mg GAE/gram fw. ANOVA revealed significant variation in total phenolic contents (F = 2.49; P < .05) across populations (Figure 1(a)). Total flavonoid contents ranged from 1.31 mg (Panuwanaula) to 1.59 mg (Khirshu) QE/gram fw, and variation across populations were significant (F = 4.39; P < .01).

Figure 1.

Total phenolic and flavonoids content (a) and antioxidant activity (b) of M. esculenta fruits; 1—Kalika; 2—Ayarpani; 3—Panuwanaula; 4—Jalna; 5—Dholichina; 6—Khirshu; 7—Shyamkhet; 8—Gwaldom; 9—Doonagiri; all values are mean of five measurements; LSD: least significance difference; levels of significance: *P < .05; **P < .01.

3.2. Antioxidant Activity

Antioxidant activity measured by three in vitro antioxidant assays, that is, free radical-scavenging ability by using ABTS radical cation (ABTS assay), DPPH radical cation (DPPH assay) and FRAP assay showed significant (P < .01) variation among populations (Figure 1(b)). As compared to other populations, fruits obtained from Ayarpani population exhibited significantly more (P < .05) antioxidant activity in all the three antioxidant assays (ABTS—1.84 mM; DPPH—2.55 mM; FRAP—2.97 mM AAE/100 g fw).

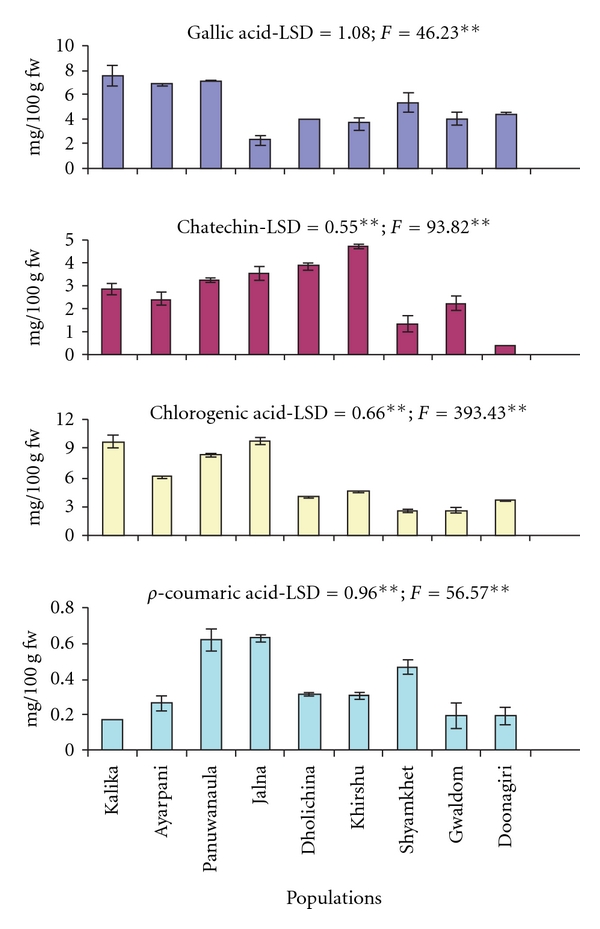

3.3. HPLC Analysis of Phenolic Compounds

Of the seven phenolic compounds used for HPLC analysis, only four (i.e., gallic acid, catechin, chlorogenic acid and ρ-coumaric acid) were detected in fruit extract of M. esculenta. These compounds showed significant (P < .01) variation across the populations (Figure 2). Quantity of chlorogenic acid was highest (5.68 mg/g fw) followed by gallic acids (5.03 mg/100 g fw), catechin (2.72 mg/100 g fw) and ρ-coumaric acid (0.35 mg/100 g fw). While considering the fruits of different origin (i.e., population), it was revealing that the quantity of detected phenolic compounds varied considerably and the difference between minimum and maximum values were about three times for gallic acid, thirteen times for catechin, four times for chlorogenic acid and ρ-coumaric acid. HPLC analysis detected only a small proportion (0.065%) of phenolics. While combining all the phenolic compounds, Kalika population showed highest total phenolics (20.23 mg/100 g, 0.14% of total phenolics). The lowest value was found for fruits of Doonagiri population (8.62 mg/100 g fw; 0.046% of total phenolics).

Figure 2.

Phenolic compounds quantified by HPLC in M. esculenta fruits; all values are mean of five measurements; LSD—least significance difference; levels of significance: **P < .01.

3.4. Relationship among Altitude, Antioxidant Assays, Total Phenolics, Flavonoids, and Phenolic Compounds

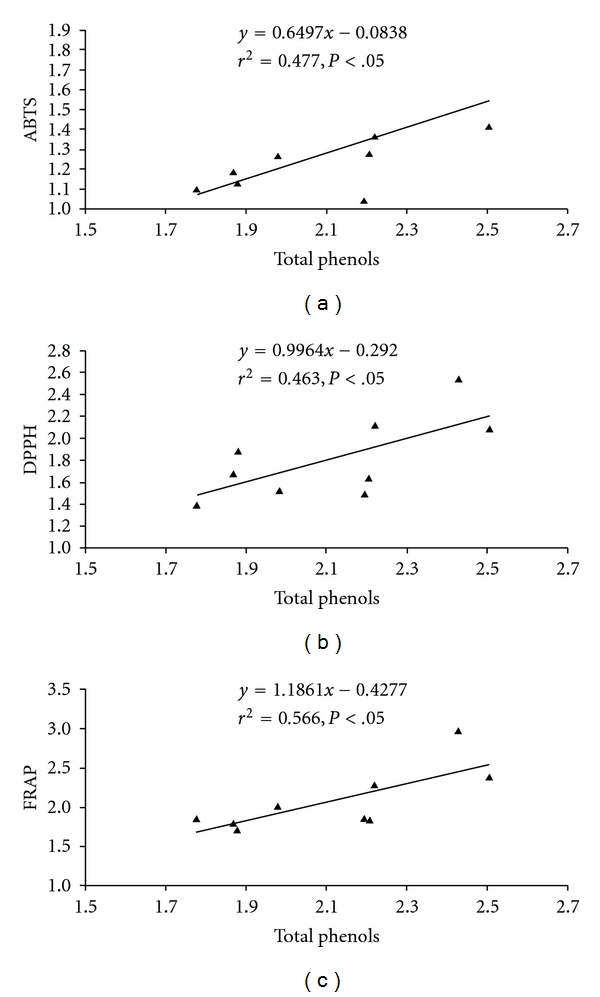

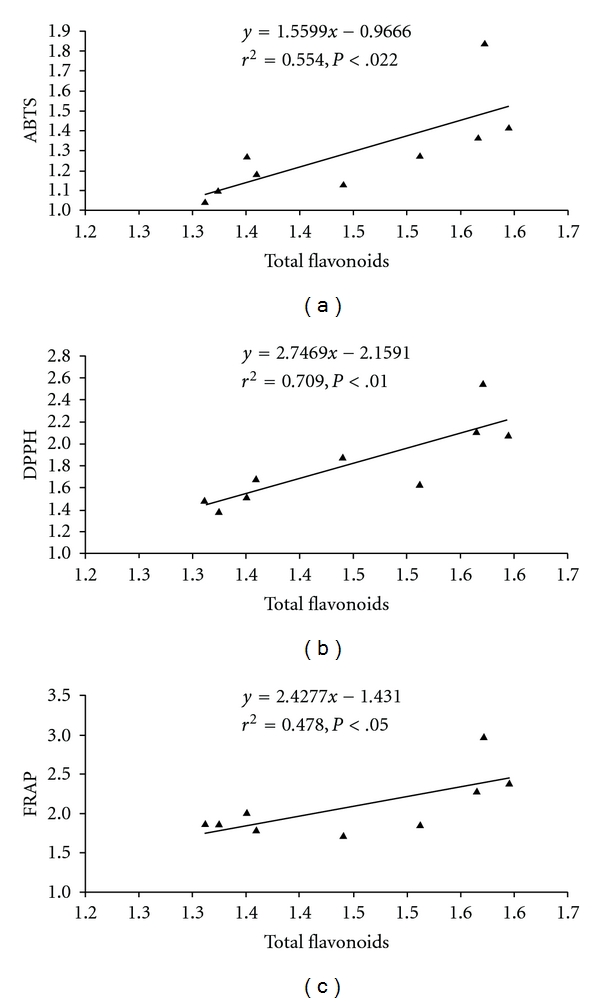

Considering altitude as an important independent variable in mountain areas, significant negative correlation with catechin (r = –0.778; P < .05) was revealing. None of other compounds exhibited significant relationship with the altitude (Table 1). However, correlation matrix showed significant (P < .05) positive impact of total phenolic and flavonoid contents on antioxidant activity (Table 1). Linear regression analysis revealed that phenolic contents contribute 46.3–47.6% of radical scavenging property (r 2 = 0.463 for DPPH and r 2 = 0.476 for ABTS) and 56.6% of reducing property (r 2 = 0.566) (Figure 3). Likewise, flavonoids contribute 55.4–70.9% radical scavenging property (r 2 = 0.554 for ABTS and r 2 = 0.709 for DPPH) and 47.8% of reducing property (r 2 = 0.478) (Figure 4). Among antioxidant assays, a strong positive relationship (P < .01) was observed. The results showed that all three in vitro antioxidant assay, used in this study, were comparable and exhibited suitability for the species. The compounds present in the methanolic extract of M. esculenta fruits were capable of scavenging ABTS·+ and DPPH· radical and also to reduce the ferric ions.

Table 1.

Correlation matrix between altitude, total phenols, total flavonoids and antioxidant activity measured by different assays in selected populations of M. esculenta (n = 9).

| r-valuea | Altitude | Total phenols | Flavonoids | ABTS | DPPH | FRAP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Altitude | 1 | |||||

| Total phenols | −0.360 | 1 | ||||

| Flavonoids | 0.004 | 0.771* | 1 | |||

| ABTS | 0.057 | 0.691* | 0.744* | 1 | ||

| DPPH | 0.176 | 0.68* | 0.843** | 0.878** | 1 | |

| FRAP | −0.132 | 0.753* | 0.691* | 0.949** | 0.856** | 1 |

| Gallic acid | −0.165 | 0.057 | 0.078 | 0.017 | 0.264 | 0.078 |

| Catechin | −0.778* | 0.256 | 0.036 | −0.215 | 0.130 | 0.036 |

| Chlorogenic acid | −0.379 | −0.404 | −0.293 | −0.371 | −0.188 | −0.293 |

| ρ-Coumaric acid | −0.101 | 0.019 | 0.078 | 0.017 | 0.264 | 0.078 |

aCorrelation coefficient.

Levels of significance: *P < .05; **P < .01.

Figure 3.

Relationship between total phenols and antioxidant activity of M. esculenta fruits following different in vitro assays (a) ABTS, (b) DPPH and (c) FRAP, (n = 9).

Figure 4.

Relationship between total flavonoids and antioxidant activity of M. esculenta fruits following different in vitro assays (a) ABTS, (b) DPPH and (c) FRAP, (n = 9).

4. Discussion

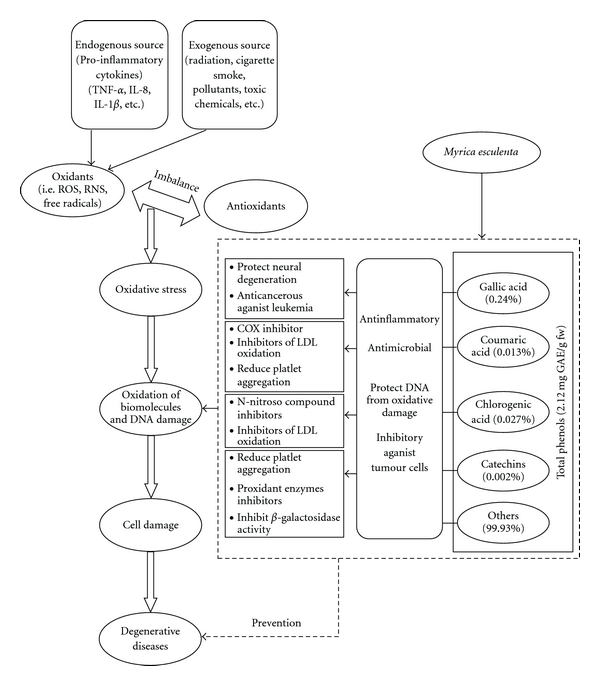

Generally, it is believed that the reactive oxygen species (ROS), reactive nitrogen species (RNS) and free radicals in the body are generated through exogenous (radiation, cigarette smoke, atmospheric pollutants, toxic chemicals, over nutrition, changing food habits, etc.) and/or endogenous sources (pro-inflammatory cytokines— tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), interleukin-8 (IL-8), interleukin-1B (IL-1B), etc. [36]). The free radicals, which are known to maintain homeostasis at the cellular level and work as signaling molecules, in excess are reported to result in oxidative stress [37] and cause various degenerative diseases [38]. In this context, antioxidants play an important role in prevention, interception and repairing of the body by stopping the formation of ROS, radical scavenging and repairing the enzymes involved in the process of cellular development [39]. Phenolics and flavonoids of plant origin are reported to have potent antioxidants and homeostatic balance between pro-oxidant and anti-oxidants is known to be important for maintenance of health as well as prevention from various degenerative diseases (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Hypothetical diagram explaining potential of M. esculenta for preventing oxidation of biomolecules, DNA damage and degenerative diseases.

Considering the target species, the mean value for total phenolic content of M. esculenta fruits (2.12 mg GAE/gram fw) was comparables with values (0.94–2.82 mg/g) reported for fruit extract of different cultivars of M. rubra [25]. As compared with M. rubra, target species (M. esculenta) possess slightly more flavonoid contents. Therefore, presence of the phenolics and flavonoid contents in relatively higher amount in M. esculenta fruits would justify its comparative advantage over M. rubra. As such, phenolics and flavanoids constitute major group of compounds which act as primary antioxidants [40] and are known to react with hydroxyl radicals [41], superoxide anion radicals [42], lipid peroxyradicals [43], protect DNA from oxidative damage, inhibitory against tumor cell and possess anti-inflammatory and antimicrobial properties. The variations in phenolic and flavonoid contents across populations may be attributed to morphological as well as biochemical characters of the fruits. This would, however, suggest source specific variation of antioxidant potential.

All of the detected phenolic compounds, albeit detected in very small proportions (0.065%), are known to have antioxidant properties. Gallic acid, which is efficiently absorbed in human body, shows positive effect against cancer cell under in vitro condition [44]. Chlorogenic acid, a very common phenolic acid present in fruits [45], and catechin are effective in preventing oxidative injuries in human epithelial cells under in vitro [46]. As such, catechins form an important group of compound in the Mediterranean diet [47]. ρ-coumaric acid is believed to reduce the risk of stomach cancer by reducing the formation of carcinogenic nitrosamines [48]. Specific function of each detected compound in M. esculenta fruits is summarized (Figure 5), thereby, highlighting antioxidant potential of the species.

Significant scavenging and reducing capacity of the fruits extract was revealing in different methods. Similar studies on M. rubra fruit extracts have established variation in antioxidant activity (1.39–6.52 mM Trolox equivalent antioxidant capacity) across cultivars [25]. However, higher antioxidant capacity has been reported in M. rubra fruit extract using DPPH and FRAP assays [27]. While considering relationship of phenolic content and antioxidant activity, the established scavenging (45–70%) and reducing (48–55%) capacity of M. esculenta fruits are indicative of their strength as an antioxidant. The remaining antioxidant activity may be attributed to other phytochemicals like anthocyanins, vitamins, carotenoids, and so forth. The reports on M. rubra have established that cyanidin-3-o-glucoside, a major anthocyanin present in the species, was responsible for 12–82% of total antioxidant activity [27].

Strong positive relationship (P < .01) of antioxidant assays suggested that all three in vitro antioxidant assays used in this study are comparable and exhibit their suitability for the species. The compounds present in the methanolic extract of the fruits of M. esculenta are not only capable for scavenging of ABTS·+ and DPPH· radical but also to reduce the ferric ions. Similar strong positive correlation of DPPH free radical scavenging ability and ferric ion reducing ability are known in wines [49] and Ilex kudingcha [50]. These results support the basic concept that antioxidants are reducing agents.

5. Conclusion

Conclusively, results of this study signify that the extract of M. esculenta fruit is an important source of natural antioxidants which can play vital role in reducing the oxidative stress and preventing from certain degenerative diseases. Purification of the extract may lead to increased activity of the compounds. On a broader perspective, considering the remoteness and poor rural settings of Uttarakhand Himalaya in India, consumption of M. esculenta fruits is likely to benefit by scavenging and reducing free radicals in the body of rural inhabitants. However, observations of significant variations in antioxidant potential and phenolics across populations can be utilized gainfully for identification of best provenances for promotion under large scale plantation through horticulture and forestry interventions.

Funding

GBPIHED in-house project (project no. 10).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr L.M.S. Palni, Director GBPIHED, for facility and encouragement. Our sincere thanks are due to Dr Uppeandra Dhar, Former Director for his constructive suggestions while designing the study. Help offered by colleagues in Biodiversity Conservation and Management thematic group of GBPIHED is thankfully acknowledged.

References

- 1.Willett WC. Balancing life-style and genomics research for disease prevention. Science. 2002;296(5568):695–698. doi: 10.1126/science.1071055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steinmetz KA, Potter JD. Vegetables, fruit, and cancer prevention: a review. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 1996;96(10):1027–1039. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(96)00273-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Narayana KR, Reddy MS, Chaluvadi MR, Krishna DR. Bioflavonoids classification, pharmacological, biochemical effects and therapeutic potential. Indian Journal of Pharmacology. 2001;33(1):2–16. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lamien-Meda A, Lamien CE, Compaoré MMY, et al. Polyphenol content and antioxidant activity of fourteen wild edible fruits from Burkina Faso. Molecules. 2008;13(3):581–594. doi: 10.3390/molecules13030581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Du G, Li M, Ma F, Liang D. Antioxidant capacity and the relationship with polyphenol and Vitamin C in Actinidia fruits. Food Chemistry. 2009;113(2):557–562. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang X-M, Yu W, Ou Z-P, Ma H-L, Liu W-M, Ji X-L. Antioxidant and immunity activity of water extract and crude polysaccharide from Ficus carica L. fruit. Plant Foods for Human Nutrition. 2009;64(2):167–173. doi: 10.1007/s11130-009-0120-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ao C, Li A, Elzaawely AA, Xuan TD, Tawata S. Evaluation of antioxidant and antibacterial activities of Ficus microcarpa L. fil. extract. Food Control. 2008;19(10):940–948. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ara JI, Nilufar N, Mosihuzzaman M, Begum R, Liaquat Azad Khan AK, Talat M. Hypoglycemic and antioxidant activities of Ficus racemosa Linn. fruits. Natural Product Research. 2009;23:399–408. doi: 10.1080/14786410802230757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang Z, Liao L, Moore J, Wu T, Wang Z. Antioxidant phenolic compounds from walnut kernels (Juglans regia L.) Food Chemistry. 2009;113(1):160–165. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sun J, Yao J, Huang S, Long X, Wang J, Garcia EG. Antioxidant activity of polyphenols and anthocyanin extracts from fruits of Kadsura coccinea (Lem.) A.C. Smith. Food Chemistry. 2009;117:276–281. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu SC, Lin JT, Wang CK, Chen HY, Yang DJ. Antioxidant properties of various solvents extracts from lychee (Litchi chinensis Sonn.) flowers. Food Chemistry. 2009;114:577–581. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gungor N, Sengul M. Antioxidant activity, total phenolic content and selected physicochemical properties of white mulberry (Morus alba L.) fruits. International Journal of Food Properties. 2008;11(1):44–52. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chirinos R, Galarza J, Betalleluz-Pallardel I, Pedreschi R, Capmos D. Antioxidant compounds and antioxidant capacity of Peruvian Camu camu (Myrciaria dubia (H.B.K.) McVaugh) fruit at different maturity stages. Food Chemistry. 2010;120(4):1019–1024. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Locatelli M, Travaglia F, Coïsson JD, Martelli A, Stévigny C, Arlorio M. Total antioxidant activity of hazelnut skin (Nocciola piemonte PGI): impact of different roasting conditions. Food Chemistry. 2010;119(4):1647–1655. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu X, Zhao M, Wang J, Yang B, Jiang Y. Antioxidant activity of methanolic extract of emblica fruits (Phyllanthus emblica L.) from six regions in China. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis. 2008;21:219–228. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Noda Y, Kaneyuki T, Mori A, Packer L. Antioxidant activities of pomegranate fruit extract and its anthocyanidins: delphinidin, cyanidin, and pelargonidin. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2002;50(1):166–171. doi: 10.1021/jf0108765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Santos-Cervantes ME, Ibarra-Zazueta ME, Loarca-Piña G, Paredes-López O, Delgado-Vargas F. Antioxidant and antimutagenic activities of Randia echinocarpa fruit. Plant Foods for Human Nutrition. 2007;62(2):71–77. doi: 10.1007/s11130-007-0044-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bhatia A, Mishra T. Free radical scavenging activity and inhibitory response of Ziziphus mauritiana (Lamk.) seeds extracts on alcohol induced oxidative stress. Journal of Complementary and Integrative Medicine. 2009;6, article no. 8 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liao H, Banbury LK, Leach DN. Antioxidant activity of 45 Chinease herbs and the relationship with their TCM chracterstics. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2007:429–434. doi: 10.1093/ecam/nem054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Veerapur VP, Prabhakar KR, Parihar VK, et al. Ficus racemosa stem bark extract: a potent antioxidant and a probable natural radioprotector. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2009;6(3):317–324. doi: 10.1093/ecam/nem119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Samant SS, Dhar U. Diversity, endemism and economic potential of wild edibles plants of Indian Himalaya. International Journal of Sustainable Development and World Ecology. 1997;4:179–191. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Osmaston AE. A Forest Flora for Kumaun. Dehradun, India: Bishen Singh Mahindra Pal Singh; 1927. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bhatt ID, Rawal RS, Dhar U. The availability, fruit yield and harvest of Myrica esculenta Buch.-Ham. ex. D. Don in Kumaun (West Himalaya) India. Mountain Research and Development. 2000;20:146–153. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gupta RK. The Living Himalaya, Vol 2. Delhi, India: Today and Tomorrow Printers and Publishers; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bao J, Cai Y, Sun M, Wang G, Corke H. Anthocyanins, flavonols, and free radical scavenging activity of Chinese Bayberry (Myrica rubra) extracts and their color properties and stability. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2005;53(6):2327–2332. doi: 10.1021/jf048312z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fang Z, Zhang M, Wang L. HPLC-DAD-ESIMS analysis of phenolic compounds in bayberries (Myrica rubra Sieb. et Zucc.) Food Chemistry. 2007;100(2):845–852. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang WS, Li X, Zheng JT, Wang GY, Sun CD, Ferguson IB. Bioactive components and antioxidant capacity of Chinese bayberry (Myrica rubra Sieb. and Zucc.) fruit in relation to fruit maturity and post harvesting storage. European Food Research and Technology. 2008;227:1091–1097. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fang Z, Zhang Y, Lu Y, et al. Phenolic compounds and antioxidant capacities of bayberry juices. Food Chemistry. 2009;113(4):884–888. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhou S-H, Fang Z-X, Lu Y, Chen J-C, Liu D-H, Ye X-Q. Phenolics and antioxidant properties of bayberry (Myrica rubra Sieb. et Zucc.) pomace. Food Chemistry. 2009;112(2):394–399. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Singleton VL, Rossi JA. Colorimetry of total phenolics with phosphomolybdic—phosphotugstic acid reagents. American Journal of Enology and Viticulture. 1965;16:144–158. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chang C-C, Yang M-H, Wen H-M, Chern J-C. Estimation of total flavonoid content in propolis by two complementary colometric methods. Journal of Food and Drug Analysis. 2002;10(3):178–182. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cai Y, Luo Q, Sun M, Corke H. Antioxidant activity and phenolic compounds of 112 traditional Chinese medicinal plants associated with anticancer. Life Sciences. 2004;74(17):2157–2184. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2003.09.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brand-Williams W, Cuvelier ME, Berset C. Use of a free radical method to evaluate antioxidant activity. Lebensmittel-Wissenschaft und-Technologie. 1995;28:25–30. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Benzie IFF, Strain JJ. The ferric reducing ability of plasma (FRAP) as a measure of ’antioxidant power’: the FRAP assay. Analytical Biochemistry. 1996;239(1):70–76. doi: 10.1006/abio.1996.0292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sndocor GW, Cochran WG. Statistical Methods. 6th edition. Iowa, USA: Iowa State University Press; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Devasagayam TPA, Tilak JC, Boloor KK, Sane KS, Ghaskadbi SS, Lele RD. Free radicals and antioxidants in human health: current status and future prospects. Journal of Association of Physicians of India. 2004;52:794–804. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sies H. Biochemistry of oxidative stress. Angewandte Chemie International. 1986;25:1058–1071. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Prakash D, Singh BN, Upadhyay G. Antioidant and free radical scavenging activities of phenols from onion (Allium cepa) Food Chemistry. 2007;102:1389–1393. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cadenas E, Packer L. Hand Book of Antioxidants. New York, NY, USA: Plenum Publishers; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Adesegun SA, Fajana A, Orabueze CI, Coker HAB. Evaluation of antioxidant properties of Phaulopsis fascisepala C.B.Cl. (Acanthaceae) Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2009;6(2):227–231. doi: 10.1093/ecam/nem098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Husain SR, Cillard J, Cillard P. Hydroxyl radical scavenging activity of flavonoids. Phytochemistry. 1987;26(9):2489–2491. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Afanaslev IB, Dorozhko AI, Bordskii AV. Chelating and free radical scavenging mechanisms of inhibitory action of rutin and quercetin in lipid peroxidation. Biochemical Pharmacology. 1989;38:1763–1769. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(89)90410-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Torel J, Cillard J, Cillard P. Antioxidant activity of flavonoids and reactivity with peroxy radical. Phytochemistry. 1986;25(2):383–385. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tomas-Barberan FA, Clifford MN. Dietary hydroxybenzoic acid derivatives—nature, occurrence and dietary burden. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture. 2000;80(7):1024–1032. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Veberic R, Colaric M, Stamper F. Phenolic acids and flavonoids of fig fruit (Ficus carica L.) in northern Mediterranean region. Food Chemistry. 2008;106:153–157. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Graziani G, D’Argenio G, Tuccillo C, et al. Apple polyphenol extracts prevent damage to human gastric epithelial cells in vitro and to rat gastric mucosa in vivo . Gut. 2005;54(2):193–200. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.046292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Auger C, Al-Awwadi N, Bornet A, et al. Catechins and procyanidins in Mediterranean diets. Food Research International. 2004;37(3):233–245. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ferguson LR, Zhu S-T, Harris PJ. Antioxidant and antigenotoxic effects of plant cell wall hydroxycinnamic acids in cultured HT-29 cells. Molecular Nutrition and Food Research. 2005;49(6):585–593. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200500014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Arnous A, Markis DP, Kefalas P. Correlation of pigments and flavanol contents with antioxidant properties in selected aged regional wines from Greece. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis. 2002;15:655–665. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liu L, Sun Y, Laura T, Liang X, Ye H, Zeng X. Determination of polyphenolic content and antioxidant activity of Kudingcha made from Ilex kudingcha C. J. Tseng. Food Chemistry. 2009;112:35–41. [Google Scholar]