Abstract

Autosomal-dominant spinocerebellar ataxias (SCAs) are a heterogeneous group of neurodegenerative disorders. In this study, we performed genetic analysis of a unique form of SCA (SCA36) that is accompanied by motor neuron involvement. Genome-wide linkage analysis and subsequent fine mapping for three unrelated Japanese families in a cohort of SCA cases, in whom molecular diagnosis had never been performed, mapped the disease locus to the region of a 1.8 Mb stretch (LOD score of 4.60) on 20p13 (D20S906–D20S193) harboring 37 genes with definitive open reading frames. We sequenced 33 of these and observed a large expansion of an intronic GGCCTG hexanucleotide repeat in NOP56 and an unregistered missense variant (Phe265Leu) in C20orf194, but we found no mutations in PDYN and TGM6. The expansion showed complete segregation with the SCA phenotype in family studies, whereas Phe265Leu in C20orf194 did not. Screening of the expansions in the SCA cohort cases revealed four additional occurrences, but none were revealed in the cohort of 27 Alzheimer disease cases, 154 amyotrophic lateral sclerosis cases, or 300 controls. In total, nine unrelated cases were found in 251 cohort SCA patients (3.6%). A founder haplotype was confirmed in these cases. RNA foci formation was detected in lymphoblastoid cells from affected subjects by fluorescence in situ hybridization. Double staining and gel-shift assay showed that (GGCCUG)n binds the RNA-binding protein SRSF2 but that (CUG)6 does not. In addition, transcription of MIR1292, a neighboring miRNA, was significantly decreased in lymphoblastoid cells of SCA patients. Our finding suggests that SCA36 is caused by hexanucleotide repeat expansions through RNA gain of function.

Main Text

Autosomal-dominant spinocerebellar ataxias (SCAs) are a heterogeneous group of neurodegenerative disorders characterized by loss of balance, progressive gait, and limb ataxia.1–3 We recently encountered two unrelated patients with intriguing clinical symptoms from a community in the Chugoku region in western mainland Japan.4 These patients both showed complicated clinical features, with ataxia as the first symptom, followed by characteristic late-onset involvement of the motor neuron system that caused symptoms similar to those of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS [MIM 105400]).4 Some SCAs (SCA1 [MIM 164400], SCA2 [MIM 183090], SCA3 [MIM 607047], and SCA6 [MIM 183086]) are known to slightly affect motor neurons; however, their involvement is minimal and the patients usually do not develop skeletal muscle and tongue atrophies.4 Of particular interest is that RNA foci have been recently demonstrated in hereditary disorders caused by microsatellite repeat expansions or insertions in the noncoding regions of their gene.5–7 The unique clinical features in these families have seldom been described in previous reports; therefore, we undertook a genetic analysis.

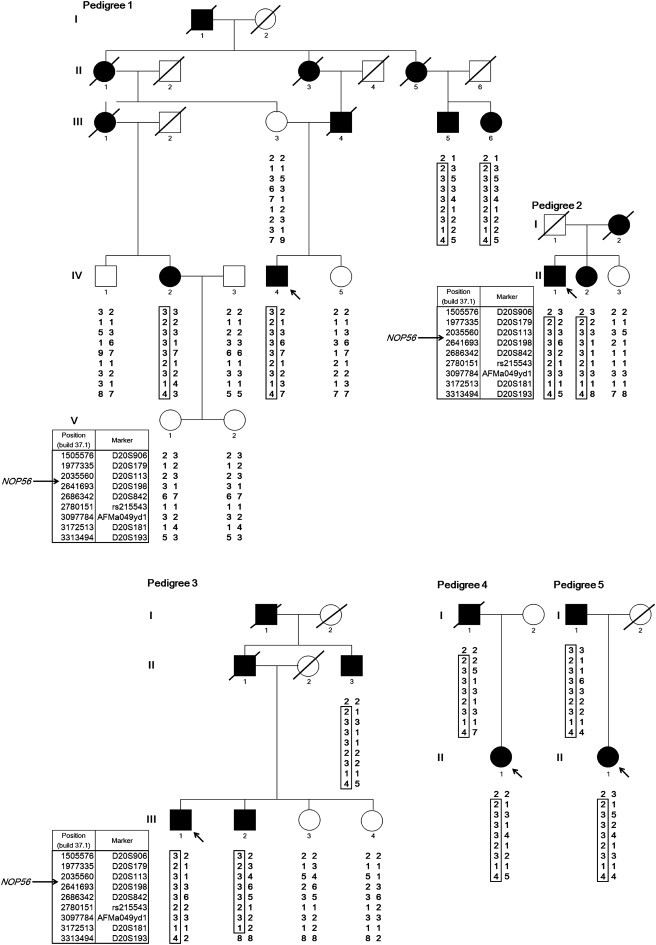

A similar form of SCA was observed in five Japanese cases from a cohort of 251 patients with SCA, in whom molecular diagnosis had not been performed, who were followed by the Department of Neurology, Okayama University Hospital. These five cases originated from a city of 450,000 people in the Chugoku region. Thus, we suspected the presence of a founder mutation common to these five cases, prompting us to recruit these five families (pedigrees 1–5) (Figure 1, Table 1). This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Kyoto University and the Okayama University institutional review board. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects. An index of cases per family was investigated in some depth: IV-4 in pedigree 1, II-1 in pedigree 2, III-1 in pedigree 3, II-1 in pedigree 4, and II-1 in pedigree 5. The mean age at onset of cerebellar ataxia was 52.8 ± 4.3 years, and the disease was transmitted by an autosomal-dominant mode of inheritance. All affected individuals started their ataxic symptoms, such as gait and truncal instability, ataxic dysarthria, and uncoordinated limbs, in their late forties to fifties. MRI revealed relatively confined and mild cerebellar atrophy (Figure 2A). Unlike individuals with previously known SCAs, all affected individuals with longer disease duration showed obvious signs of motor neuron involvement (Table 1). Characteristically, all affected individuals exhibited tongue atrophy with fasciculation, although its degree of severity varied (Figure 2B). Despite severe tongue atrophy in some cases, their swallowing function was relatively preserved, and they were allowed oral intake even at a later point after onset. In addition to tongue atrophy, skeletal muscle atrophy and fasciculation in the limbs and trunk appeared in advanced cases.4 Tendon reflexes were generally mildly to severely hyperreactive in most affected individuals, none of whom displayed severe lower limb spasticity or extensor plantar response. Electrophysiological studies were performed in an affected individual. Nerve conduction studies revealed normal findings in all of the cases that were examined; however, an electromyogram showed neurogenic changes only in cases with skeletal muscle atrophy, indicating that lower motor neuropathy existed in this particular disease. Progression of motor neuron involvement in this SCA was typically limited to the tongue and main proximal skeletal muscles in both upper and lower extremities, which is clearly different from typical ALS, which usually involves most skeletal muscles over the course of a few years, leading to fatal results within several years.

Figure 1.

Pedigree Charts of the Five SCA Families

Haplotypes are shown for nine markers from D20S906 (1,505,576 bp) to D20S193 (3,313,494 bp), spanning 1.8 Mb on chromosome 20p13. NOP56 is located at 2,633,254–2,639,039 bp (NCBI build 37.1). Filled and unfilled symbols indicate affected and unaffected individuals, respectively. Squares and circles represent males and females, respectively. A slash indicates a deceased individual. The putative founder haplotypes among patients are shown in boxes constructed by GENHUNTER.8 Arrows indicate the index case. The pedigrees were slightly modified for privacy protection.

Table 1.

Clinical Characteristics of Affected Subjects

| Pedigree No. | Patient ID | Gender | Onset Age (yr) | Current Age (yr) | Ataxia |

Motor Neuron Involvement |

Genotype of GGCCTG Repeats | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skeletal Muscle Atrophy | Skeletal Muscle Fasciculation | Tongue Atrophy/ Fasciculation | |||||||

| 1 | III-5 | M | 50 | 70 | +++ | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | g.263397_263402[6]+(1800) |

| III-6 | F | 52 | 68 | ++ | + | + | + | g.263397_263402[6]+(2300) | |

| IV-2 | F | 57 | 63 | + | - | - | + | g.263397_263402[6]+(2300) | |

| IV-4 | M | 50 | 59 | + | - | - | + | g.263397_263402[6]+(2300) | |

| 2 | II-1 | M | 55 | 77 | +++ | ++ | + | + | g.263397_263402[6]+(2200) |

| II-2 | F | 53 | 70 | ++ | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | g.263397_263402[6]+(2200) | |

| 3 | II-3 | M | 58 | 77 | ++ | ++ | + | + | g.263397_263402[3]+(2300) |

| III-1 | M | 56 | 62 | + | - | - | ± | g.263397_263402[8]+(2200) | |

| III-2 | M | 51 | 61 | ++ | + | + | + | g.263397_263402[6]+(1800) | |

| 4 | I-1 | M | 57 | died in 2001 at 83 | ++ | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | g.263397_263402[5]+(1800) |

| II-1 | F | 48 | 61 | ++ | + | ± | ++ | g.263397_263402[6]+(2000) | |

| 5 | I-1 | M | 57 | 86 | ++ | +++ | + | + | g.263397_263402[5]+(2000) |

| II-1 | F | 47 | 58 | ++ | + | + | + | g.263397_263402[8]+(1700) | |

| SCA#1 | M | 52 | 69 | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | g.263397_263402[5]+(2200) | |

| SCA#2 | F | 43 | 53 | +++ | - | - | + | g.263397_263402[6]+(1800) | |

| SCA#3 | M | 55 | 60 | ++ | - | - | ++ | g.263397_263402[8]+(1700) | |

| SCA#4 | M | 57 | 81 | +++ | + | + | +++ | g.263397_263402[5]+(2200) | |

| Mean | 52.8 | ||||||||

| SD | 4.3 | ||||||||

N.D., not determined.

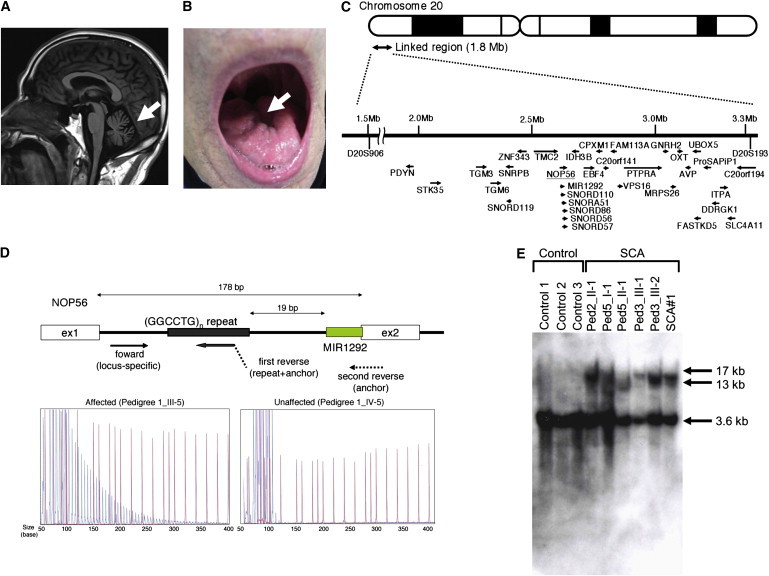

Figure 2.

Motor Neuron Involvement and (GGCCTG)n Expansion in the First Intron of NOP56

(A) MRI of an affected subject (SCA#3) showed mild cerebellar atrophy (arrow) but no other cerebral or brainstem pathology.

(B) Tongue atrophy (arrow) was observed in SCA#1.

(C) Physical map of the 1.8-Mb linkage region from D20S906 (1,505,576 bp) to D20S193 (3,313,494 bp), with 33 candidate genes shown, as well as the direction of transcription (arrows).

(D) The upper portion of the panel shows the scheme of primer binding for repeat-primer PCR analysis. In the lower portion, sequence traces of the PCR reactions are shown. Red lines indicate the size markers. The vertical axis indicates arbitrary intensity levels. A typical saw-tooth pattern is observed in an affected pedigree.

(E) Southern blotting of LCLs from SCA cases and three controls. Genomic DNA (10 μg) was extracted from Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-immortalized LCLs derived from six affected subjects (Ped2_II-1, Ped3_III-1, Ped3_III-2, Ped5_I-1, Ped5_II-1, and SCA#1) and digested with 2 U of AvrII overnight (New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA, USA). A probe covering exon 4 of NOP56 (452 bp) was subjected to PCR amplification from human genomic DNA with the use of primers (Table S3) and labeled with 32P-dCTP.

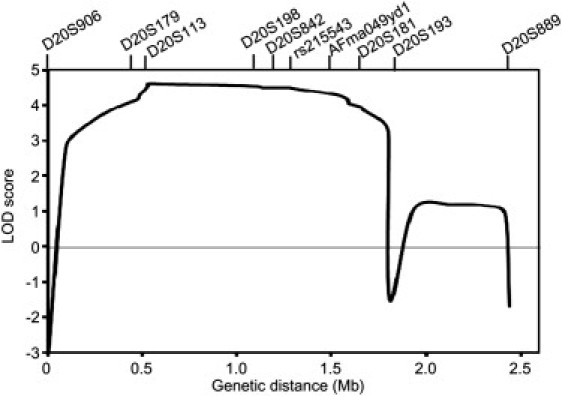

We conducted genome-wide linkage analysis for nine affected subjects and eight unaffected subjects in three informative families (pedigrees 1–3; Figure 1). For genotyping, we used an ABI Prism Linkage Mapping Set (Version 2; Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) with 382 markers, 10 cM apart, for 22 autosomes. Fine-mapping markers (approximately 1 cM apart) were designed according to information from the uniSTS reference physical map in the NCBI database. A parametric linkage analysis was carried out in GENEHUNTER8 with the assumption of an autosomal-dominant model. The disease allele frequency was set at 0.000001, and a phenocopy frequency of 0.000001 was assumed. Population allele frequencies were assigned equal portions of individual alleles. We performed multipoint analyses for autosomes and obtained LOD scores. We considered LOD scores above 3.0 to be significant.8 Genome-wide linkage analysis revealed a single locus on chromosome 20p13 with a LOD score of 3.20. Fine mapping increased the LOD score to 4.60 (Figure 3). Haplotype analysis revealed two recombination events in pedigree 3, delimiting a1.8 Mb region (D20S906–D20S193) (Figure 1). We further tested whether the five cases shared the haplotype. As shown in Figure 1, pedigrees 4 and 5 were confirmed to have the same haplotype as pedigrees 1, 2, and 3, indicating that the 1.8 Mb region is very likely to be derived from a common ancestor.

Figure 3.

Multipoint Linkage Analysis with Ten Markers on Chromosome 20p13

The 1.8 Mb region harbors 44 genes (NCBI, build 37.1). We eliminated two pseudogenes and five genes (LOC441938, LOC100289473, LOC100288797, LOC100289507, and LOC100289538) from the candidates. Evidence view showed that the first, fourth, and fifth genes were not found in the contig in this region, whereas the second and third genes are not assigned to orthologous loci in the mouse genome. Sequence similarities among paralog genes defied direct sequencing of four genes: SIRPD [NM 178460.2], SIRPB1 [NM 603889], SIRPG [NM 605466], and SIRPA [NM 602461]. Thus, we sequenced 33 of 37 genes (PDYN [MIM 131340], STK35 [MIM 609370], TGM3 [MIM 600238], TGM6 [NM_198994.2], SNRPB [MIM 182282], SNORD119 [NR_003684.1], ZNF343 [NM_024325.4], TMC2 [MIM 606707], NOP56 [NM_006392.2], MIR1292 [NR_031699.1], SNORD110 [NR_003078.1], SNORA51 [NR_002981.1], SNORD86 [NR_004399.1], SNORD56 [NR_002739.1], SNORD57 [NR_002738.1], IDH3B [MIM 604526], EBF4 [MIM 609935], CPXM1 [NM_019609.4], C20orf141 [NM_080739.2], FAM113A [NM_022760.3], VPS16 [MIM 608550], PTPRA [MIM 176884], GNRH2 [MIM 602352], MRPS26 [MIM 611988], OXT [MIM 167050], AVP [MIM 192340], UBOX5 [NM_014948.2], FASTKD5 [NM_021826.4], ProSAPiP1 [MIM 610484], DDRGK1 [NM_023935.1], ITPA [MIM 147520], SLC4A11 [MIM 610206], and C20orf194 [NM_001009984.1]) (Figure 2C). All noncoding and coding exons, as well as the 100 bp up- and downstream of the splice junctions of these genes, were sequenced in two index cases (IV-4 in pedigree1 and III-1 in pedigree 3) and in three additional cases (II-1 in pedigree 2, II-1 in pedigree 4, and II-1 in pedigree 5) with the use of specific primers (Table S1 available online). Eight unregistered variants were found among the two index cases. Among these, there was a coding variant, c.795C>G (p.Phe265Leu), in C20orf194, whereas the other seven included one synonymous variant, c.1695T>A (p.Leu565Leu), in ZNF343 and six non-splice-site intronic variants (Table S2). We tested segregation by sequencing exon 11 of C20orf194 in IV-2 and III-5 in pedigree 1. Neither IV-2 nor III-5 had this variant. We thus eliminated C20orf194 as a candidate. Missense mutations in PDYN and TGM6, which have been recently reported as causes of SCA, mapped to 20p12.3-p13,9,10 but none were detected in the five index cases studied here (Table S2).

Possible expansions of repetitive sequences in these 33 genes were investigated when intragenic repeats were indicated in the database (UCSC Genome Bioinformatics). Expansions of the hexanucleotide repeat GGCCTG (rs68063608) were found in intron 1 of NOP56 (Figure 2D) in all five index cases through the use of a repeat-primed PCR method.11–13 An outline of the repeat-primed PCR experiment is described in Figure 2D. In brief, the fluorescent-dye-conjugated forward primer corresponded to the region upstream of the repeat of interest. The first reverse primer consisted of four units of the repeat (GGCCTG) and a 5′ tail used as an anchor. The second reverse primer was an “anchor” primer. These primers are described in Table S3. Complete segregation of the expanded hexanucleotide was confirmed in all pedigrees, and the maximum repeat size in nine unaffected members was eight (data not shown).

In addition to the SCA cases in five pedigrees, four unrelated cases (SCA#1–SCA#4) were found to have a (GGCCTG)n allele through screening of the cohort SCA patients (Table 1). Neurological examination was reevaluated in these four cases, revealing both ataxia and motor neuron dysfunction with tongue atrophy and fasciculation (Table 1). In total, nine unrelated cases were found in the 251 cohort patients with SCA (3.6%). For confirmation of the repeat expansions, Southern blot analysis was conducted in six affected subjects (Ped2_II-1, Ped3_III-1, Ped3_III-2, Ped5_I-1, Ped5_II-1, and SCA#1). The data showed >10 kb of repeat expansions in the lymphoblastoid cell lines (LCLs) obtained from the SCA patients (Figure 2E). Furthermore, the numbers of GGCCTG repeat expansion were estimated by Southern blotting in 11 other cases. The expansion analysis revealed approximately 1500 to 2500 repeats in 17 cases (Table 1). There was no negative association between age at onset and the number of GGCCTG repeats (n = 17, r = 0.42, p = 0.09; Figure S1) and no obvious anticipation in the current pedigrees.

To investigate the disease specificity and disease spectrum of the hexanucleotide repeat expansions, we tested the repeat expansions in an Alzheimer disease (MIM 104300) cohort and an ALS cohort followed by the Department of Neurology, Okayama University Hospital. We also recruited Japanese controls, who were confirmed to be free from brain lesions through MRI and magnetic resonance angiography, which was performed as described previously.14 Screening of the 27 Alzheimer disease cases and 154 ALS cases failed to detect additional cases with repeat expansions. The GGCCTG repeat sizes ranged from 3 to 8 in 300 Japanese controls (5.9 ± 0.8 repeats), suggesting that the >10 kb repeat expansions were mutations.

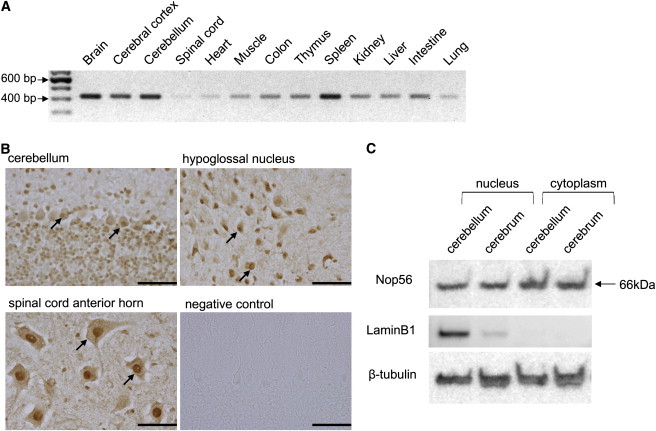

Expression of Nop56, an essential component of the splicing machinery,15 was examined by RT-PCR with the use of primers for wild-type mouse Nop56 cDNA (Table S3). Expression of Nop56 mRNA was detected in various tissues, including CNS tissue, and a very weak signal was detected in spinal cord tissue (Figure 4A). Immunohistochemistry using an anti-mouse Nop56 antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) detected the Nop56 protein in Purkinje cells of the cerebellum as well as motor neurons of the hypoglossal nucleus and the spinal cord anterior horn (Figure 4B), suggesting that these cells may be responsible for tongue and muscle atrophy in the trunk and limbs, respectively. Immunoblotting also confirmed the presence of Nop56 in neural tissues (Figure 4C), where Nop56 is localized in both the nucleus and cytoplasm.

Figure 4.

Nop56 in the Mouse Nervous System

(A) RT-PCR analysis of Nop56 (422 bp) in various mouse tissues. cDNA (25 ng) collected from various organs of C57BL/6 mice was purchased from GenoStaf (Tokyo, Japan).

(B) Immunohistochemical analysis of Nop56 in the cerebellum, hypoglossal nucleus, and spinal cord anterior horn in wild-type male Slc:ICR mice at 8 wks of age (Japan SLC, Shizuoka, Japan). The arrows indicate anti- Nop56 antibody staining. The negative control was the cerebellar sample without the Nop56 antibody treatment. Scale bar represents 100 μm.

(C) Immunoblotting of Nop56 (66 kDa) in the cerebellum and cerebrum. Protein sample (10 μg) was subjected to immunoblotting. LaminB1, a nuclear protein, and beta-tubulin were used as loading controls.

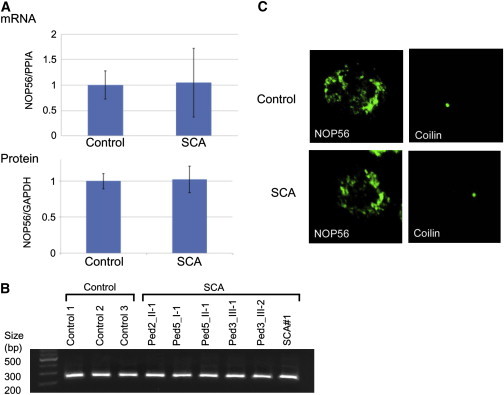

Alterations of NOP56 RNA expression and protein levels in LCLs from patients were examined by real-time RT-PCR and immunoblotting. The primers for quantitative PCR of human NOP56 cDNA are described in Table S3. Immunoblotting was performed with the use of an anti-human NOP56 antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA). We found no decrease in NOP56 RNA expression or protein levels in LCLs from these patients (Figure 5A). To investigate abnormal splicing variants of NOP56, we performed RT-PCR using the primers covering the region from the 5′ UTR to exon 4 around the repeat expansion (Table S3); however, no splicing variant was observed in LCLs from the cases (Figure 5B). We also performed immunocytochemistry for NOP56 and coilin, a marker of the Cajal body, where NOP56 functions.16 NOP56 and coilin distributions were not altered in LCLs of the SCA patients (Figure 5C), suggesting that qualitative or quantitative changes in the Cajal body did not occur. These results indicated that haploinsufficiency could not explain the observed phenotype.

Figure 5.

Analysis of NOP56 in LCLs from SCA Patients

(A) mRNA expression (upper panel) and protein levels (lower panel) in LCLs from cases (n = 6) and controls (n = 3) were measured by RT-PCR and immunoblotting, respectively. cDNA (10 ng) was transcribed from total RNA isolated from LCLs and used for RT-PCR. Immunoblotting was performed with the use of a protein sample (40 μg) extracted from LCLs. The data indicate the mean ± SD relative to the levels of PP1A and GAPDH, respectively. There was no significant difference between LCLs from controls and cases.

(B) Analysis for splicing variants of NOP56 cDNA. RT-PCR with 10 ng of cDNA and primers corresponding to the region from the 5′ UTR to exon 4 around the repeat expansion was performed. The PCR product has an expected size of 230 bp.

(C) Immunocytochemistry for NOP56 and coilin. Green signals represent NOP56 or coilin. Shown are representative samples from 100 observations of controls or cases.

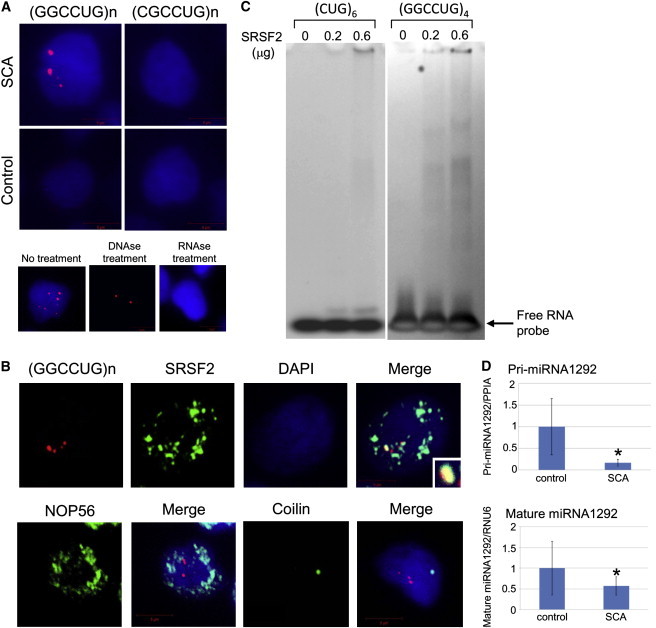

We performed fluorescence in situ hybridization to detect RNA foci containing the repeat transcripts in LCLs from patients, as previously described.17,18 Lymphoblastoid cells from two SCA patients (Ped2_II-2 and Ped5_I-1) and two control subjects were analyzed. An average of 2.1 ± 0.5 RNA foci per cell were detected in 57.0% of LCLs (n = 100) from the SCA subjects through the use of a nuclear probe targeting the GGCCUG repeat, whereas no RNA foci were observed in control LCLs (n = 100) (Figure 6A). In contrast, a probe for the CGCCUG repeat, another repeat sequence in intron 1 of NOP56, detected no RNA foci in either SCA or control LCLs (n = 100 each) (Figure 6A), indicating that the GGCCUG repeat was specifically expanded in the SCA subjects. The specificity of the RNA foci was confirmed by sensitivity to RNase A treatment and resistance to DNase treatment (Figure 6A).

Figure 6.

RNA Foci Formation and Decreased Transcription of MIR1292

(A) Cells were fixed on coverslips and then hybridized with solutions containing either a Cy3-labeled C(CAGGCC)2CAG or G(CAGGCG)2CAG oligonucleotide probe (1 ng/μl). For controls, the cells were treated with 1000 U/ml DNase or 100 μg/ml RNase for 1 hr at 37°C prior to hybridization, as indicated. After a wash step, coverslips were placed on the slides in the presence of ProLong Gold with DAPI mounting media (Molecular Probes, Tokyo, Japan) and photographed with a fluorescence microscope. The upper panels indicate LCLs from an SCA case and a control hybridized with C(CAGGCC)2CAG (left) or G(CAGGCG)2CAG (right). Red and blue signals represent RNA foci and the nucleus (DAPI staining), respectively. Similar RNA foci formation was confirmed in LCLs from another index case. The lower panels show RNA foci in SCA LCLs treated with DNase or RNase.

(B) Double staining was performed with the probe for (GGCCUG)n (red) and anti-SRSF2, NOP56, or coilin antibody (green).

(C) Gel-shift assays revealed specific binding of SRSF2 to (GGCCUG)4 but little to (CUG)6.

(D) RNA samples (10 ng) were extracted from LCLs of controls (n = 3) and cases (n = 6). MiRNAs were measured with the use of a TaqMan probe for precursor (Pri-) and mature MIR1292. The data indicate the mean ± SD, relative to the levels of PP1A or RNU6. ∗: p < 0.05.

Several reports have suggested that RNA foci play a role in the etiology of SCA through sequestration of specific RNA-binding proteins.5–7 In silico searches (ESEfinder 3.0) predicted an RNA-binding protein, SRSF2 (MIM 600813), as a strong candidate for binding of the GGCCUG repeat. Double staining with the probe for the GGCCUG repeat and an anti-SRSF2 antibody (Sigma-Aldrich, Tokyo, Japan) was performed. The results showed colocalization of RNA foci with SRSF2, whereas NOP56 and coilin were not colocalized with the RNA foci (Figure 6B), suggesting a specific interaction of endogenous SRSF2 with the RNA foci in vivo.

To further confirm the interaction, gel-shift assays were carried out for investigation of the binding activity of SRSF2 with (GGCCUG)n. Synthetic RNA oligonucleotides (200 pmol), (GGCCUG)4 or (CUG)6, which is the latter part of the hexanucleotide, as well as the repeat RNA involved in myotonic dystrophy type 1 (DM1 [MIM 160900])18 and SCA8 (MIM 608768),5 were denatured and immediately mixed with different amounts (0, 0.2, or 0.6 μg) of recombinant full-length human SRSF2 (Abcam, Cambridge, UK). The mixtures were incubated, and the protein-bound probes were separated from the free forms by electrophoresis on 5%–20% native polyacrylamide gels. The separated RNA probes were detected with SYBR Gold staining (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). We found a strong association of (GGCCUG)4 with SRSF2 in vitro in comparison to (CUG)6 (Figure 6C). Collectively, we concluded that (GGCCUG)n interacts with SRSF2.

It is notable that MIR1292 is located just 19 bp 3′ of the GGCCTG repeat (Figure 2D). MiRNAs such as MIR1292 are small noncoding RNAs that regulate gene expression by inhibiting translation of specific target mRNAs.19,20 MiRNAs are believed to play important roles in key molecular pathways by fine-tuning gene expression.19,20 Recent studies have revealed that miRNAs influence neuronal survival and are also associated with neurodegenerative diseases.21,22 In silico searches (Target Scan Human 5.1) predicted glutamate receptors (GRIN2B [MIM 138252] and GRIK3 [MIM 138243]) to be potential target genes. Real-time RT-PCR using TaqMan probes for miRNA (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) revealed that the levels of both mature and precursor MIR1292 were significantly decreased in SCA LCLs (Figure 6D), indicating that the GGCCTG repeat expansion decreased the transcription of MIR1292. A decrease in MIR1292 expression may upregulate glutamate receptors in particular cell types; e.g., GRIK3 in stellate cells in the cerebellum,23 leading to ataxia because of perturbation of signal transduction to the Purkinje cells. In addition, it has been suggested, on the basis of ALS mouse models,24,25 that excitotoxicity mediated by a type of glutamate receptor, the NMDA receptor including GRIN2B, is involved in loss of spinal neurons. A very slowly progressing and mild form of the motor neuron disease, such as that described here, which is limited to mostly fasciculation of the tongue, limbs and trunk, may also be compatible with such a functional dysregulation rather than degeneration.

In the present study, we have conducted genetic analysis to find a genetic cause for the unique SCA with motor neuron disease. With extensive sequencing of the 1.8 Mb linked region, we found large hexanucleotide repeat expansions in NOP56, which were completely segregated with SCA in five pedigrees and were found in four unrelated cases with a similar phenotype. The expansion was not found in 300 controls or in other neurodegenerative diseases. We further proved that repeat expansions of NOP56 induce RNA foci and sequester SRSF2. We thus concluded that hexanucleotide repeat expansions are considered to cause SCA by a toxic RNA gain-of-function mechanism, and we name this unique SCA as SCA36. Haplotype analysis indicates that hexanucleotide expansions are derived from a common ancestor. The prevalence of SCA36 was estimated at 3.6% in the SCA cohort in Chugoku district, suggesting that prevalence of SCA36 may be geographically limited to the western part of Japan and is rare even in Japanese SCAs.

Expansion of tandem nucleotide repeats in different regions of respective genes (most often the triplets CAG and CTG) has been shown to cause a number of inherited diseases over the past decades. An expansion in the coding region of a gene causes a gain of toxic function and/or reduces the normal function of the corresponding protein at the protein level. RNA-mediated noncoding repeat expansions have also been identified as causing eight other neuromuscular disorders: DM1, DM2 (MIM 602668), fragile X tremor/ataxia syndrome (FXTAS [MIM 300623]), Huntington disease-like 2 (HDL2 [MIM 606438]), SCA8, SCA10 (MIM 603516), SCA12 (MIM 604326), and SCA31 (MIM 117210).26 The repeat numbers in affected alleles of SCA36 are among the largest seen in this group of diseases (i.e., there are thousands of repeats). Moreover, SCA36 is not merely a nontriplet repeat expansion disorder similar to SCA10, DM2, and SCA31, but is now proven to be a human disease caused by a large hexanucleotide repeat expansion. In addition, no or only weak anticipation has been reported for noncoding repeat expansion in SCA, whereas clear anticipation has been reported for most polyglutamine expansions in SCA.2 As such, absence of anticipation in SCA36 is in accord with previous studies on SCAs with noncoding repeat expansions. The common hallmark in these noncoding repeat expansion disorders is transcribed repeat nuclear accumulations with respective repeat RNA-binding proteins, which are considered to primarily trigger and develop the disease at the RNA level. However, multiple different mechanisms are likely to be involved in each disorder. There are at least two possible explanations for the motor neuron involvement of SCA36: gene- and tissue-specific splicing specificity of SRSF2 and involvement of miRNA. In SCA36, there is the possibility that the adverse effect of the expansion mutation is mediated by downregulation of miRNA expression. The biochemical implication of miRNA involvement cannot be evaluated in this study, because availability of tissue samples from affected cases was limited to LCLs. Given definitive downregulation of miRNA 1292 in LCLs, we should await further study to substantiate its involvement in affected tissues. Elucidating which mechanism(s) plays a critical role in the pathogenesis will be required for determining whether cerebellar degeneration and motor neuron disease occur through a similar scenario.

In conclusion, expansion of the intronic GGCCTG hexanucleotide repeat in NOP56 causes a unique form of SCA, SCA36, which shows not only ataxia but also motor neuron dysfunction. This characteristic disease phenotype can be explained by the combination of RNA gain of function and MIR1292 suppression. Additional studies are required to investigate the roles of each mechanistic component in the pathogenesis of SCA36.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported mainly by grants to A.K. and partially by grants to T.M., Y.I., H.K., and K.A. We thank Norio Matsuura, Kokoro Iwasawa, and Kouji H. Harada (Kyoto University Graduate School of Medicine).

Supplemental Data

Web Resources

The URLs for data presented herein are as follows:

ESEfinder 3.0, http://rulai.cshl.edu/cgi-bin/tools/ESE3/esefinder.cgi?process=home

Target Scan Human 5.1, http://www.targetscan.org/

UCSC Genome Bioinformatics, http://genome.ucsc.edu

References

- 1.Harding A.E. The clinical features and classification of the late onset autosomal dominant cerebellar ataxias. A study of 11 families, including descendants of the ‘the Drew family of Walworth’. Brain. 1982;105:1–28. doi: 10.1093/brain/105.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Matilla-Dueñas A., Sánchez I., Corral-Juan M., Dávalos A., Alvarez R., Latorre P. Cellular and molecular pathways triggering neurodegeneration in the spinocerebellar ataxias. Cerebellum. 2010;9:148–166. doi: 10.1007/s12311-009-0144-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schöls L., Bauer P., Schmidt T., Schulte T., Riess O. Autosomal dominant cerebellar ataxias: clinical features, genetics, and pathogenesis. Lancet Neurol. 2004;3:291–304. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(04)00737-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ohta Y., Hayashi T., Nagai M., Okamoto M., Nagotani S., Nagano I., Ohmori N., Takehisa Y., Murakami T., Shoji M. Two cases of spinocerebellar ataxia accompanied by involvement of the skeletal motor neuron system and bulbar palsy. Intern. Med. 2007;46:751–755. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.46.6261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Daughters R.S., Tuttle D.L., Gao W., Ikeda Y., Moseley M.L., Ebner T.J., Swanson M.S., Ranum L.P. RNA gain-of-function in spinocerebellar ataxia type 8. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000600. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sato N., Amino T., Kobayashi K., Asakawa S., Ishiguro T., Tsunemi T., Takahashi M., Matsuura T., Flanigan K.M., Iwasaki S. Spinocerebellar ataxia type 31 is associated with “inserted” penta-nucleotide repeats containing (TGGAA)n. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2009;85:544–557. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.White M.C., Gao R., Xu W., Mandal S.M., Lim J.G., Hazra T.K., Wakamiya M., Edwards S.F., Raskin S., Teive H.A. Inactivation of hnRNP K by expanded intronic AUUCU repeat induces apoptosis via translocation of PKCdelta to mitochondria in spinocerebellar ataxia 10. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1000984. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kruglyak L., Daly M.J., Reeve-Daly M.P., Lander E.S. Parametric and nonparametric linkage analysis: a unified multipoint approach. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1996;58:1347–1363. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bakalkin G., Watanabe H., Jezierska J., Depoorter C., Verschuuren-Bemelmans C., Bazov I., Artemenko K.A., Yakovleva T., Dooijes D., Van de Warrenburg B.P. Prodynorphin mutations cause the neurodegenerative disorder spinocerebellar ataxia type 23. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2010;87:593–603. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang J.L., Yang X., Xia K., Hu Z.M., Weng L., Jin X., Jiang H., Zhang P., Shen L., Guo J.F. TGM6 identified as a novel causative gene of spinocerebellar ataxias using exome sequencing. Brain. 2010;133:3510–3518. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cagnoli C., Michielotto C., Matsuura T., Ashizawa T., Margolis R.L., Holmes S.E., Gellera C., Migone N., Brusco A. Detection of large pathogenic expansions in FRDA1, SCA10, and SCA12 genes using a simple fluorescent repeat-primed PCR assay. J. Mol. Diagn. 2004;6:96–100. doi: 10.1016/S1525-1578(10)60496-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Matsuura T., Ashizawa T. Polymerase chain reaction amplification of expanded ATTCT repeat in spinocerebellar ataxia type 10. Ann. Neurol. 2002;51:271–272. doi: 10.1002/ana.10049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Warner J.P., Barron L.H., Goudie D., Kelly K., Dow D., Fitzpatrick D.R., Brock D.J. A general method for the detection of large CAG repeat expansions by fluorescent PCR. J. Med. Genet. 1996;33:1022–1026. doi: 10.1136/jmg.33.12.1022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hashikata H., Liu W., Inoue K., Mineharu Y., Yamada S., Nanayakkara S., Matsuura N., Hitomi T., Takagi Y., Hashimoto N. Confirmation of an association of single-nucleotide polymorphism rs1333040 on 9p21 with familial and sporadic intracranial aneurysms in Japanese patients. Stroke. 2010;41:1138–1144. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.576694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wahl M.C., Will C.L., Lührmann R. The spliceosome: design principles of a dynamic RNP machine. Cell. 2009;136:701–718. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lechertier T., Grob A., Hernandez-Verdun D., Roussel P. Fibrillarin and Nop56 interact before being co-assembled in box C/D snoRNPs. Exp. Cell Res. 2009;315:928–942. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2009.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liquori C.L., Ricker K., Moseley M.L., Jacobsen J.F., Kress W., Naylor S.L., Day J.W., Ranum L.P. Myotonic dystrophy type 2 caused by a CCTG expansion in intron 1 of ZNF9. Science. 2001;293:864–867. doi: 10.1126/science.1062125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Taneja K.L., McCurrach M., Schalling M., Housman D., Singer R.H. Foci of trinucleotide repeat transcripts in nuclei of myotonic dystrophy cells and tissues. J. Cell Biol. 1995;128:995–1002. doi: 10.1083/jcb.128.6.995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Winter J., Jung S., Keller S., Gregory R.I., Diederichs S. Many roads to maturity: microRNA biogenesis pathways and their regulation. Nat. Cell Biol. 2009;11:228–234. doi: 10.1038/ncb0309-228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhao Y., Srivastava D. A developmental view of microRNA function. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2007;32:189–197. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2007.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eacker S.M., Dawson T.M., Dawson V.L. Understanding microRNAs in neurodegeneration. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2009;10:837–841. doi: 10.1038/nrn2726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hébert S.S., De Strooper B. Alterations of the microRNA network cause neurodegenerative disease. Trends Neurosci. 2009;32:199–206. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2008.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tsuzuki, K., and Ozawa, S. (2005). Glutamate Receptors. Encyclopedia of life sciences. John Wiley and Sons, Ltd., http://onlinelibrary.com/doi/10.1038/npg.els.0005056.

- 24.Nutini M., Frazzini V., Marini C., Spalloni A., Sensi S.L., Longone P. Zinc pre-treatment enhances NMDAR-mediated excitotoxicity in cultured cortical neurons from SOD1(G93A) mouse, a model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neuropharmacology. 2011;60:1200–1208. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2010.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sanelli T., Ge W., Leystra-Lantz C., Strong M.J. Calcium mediated excitotoxicity in neurofilament aggregate-bearing neurons in vitro is NMDA receptor dependant. J. Neurol. Sci. 2007;256:39–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2007.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Todd P.K., Paulson H.L. RNA-mediated neurodegeneration in repeat expansion disorders. Ann. Neurol. 2010;67:291–300. doi: 10.1002/ana.21948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.