Abstract

3-M syndrome, a primordial growth disorder, is associated with mutations in CUL7 and OBSL1. Exome sequencing now identifies mutations in CCDC8 as a cause of 3-M syndrome. CCDC8 is a widely expressed gene that is transcriptionally associated to CUL7 and OBSL1, and coimmunoprecipitation indicates a physical interaction between CCDC8 and OBSL1 but not CUL7. We propose that CUL7, OBSL1, and CCDC8 are members of a pathway controlling mammalian growth.

Main Text

3-M syndrome (MIM 273750 and 612921), named after the three principle geneticists who first described the condition,1 is an autosomal-recessive condition characterized by severe postnatal growth restriction that results in significantly short stature (typical final adult height of 120–130 cm).1–3 The syndrome is also associated with distinctive facial dysmorphism, including triangular facies, frontal bossing, midface hypoplasia, fleshy tipped nose, and full fleshy lips. Prominent heels are also evident in younger individuals with 3-M syndrome. Skeletal abnormalities including slender tubular bones and relatively tall vertebral bodies are seen in some individuals. The condition is associated with normal intelligence.1–3 In 2005, autozygosity mapping revealed a 3-M syndrome locus on chromosome 6p21.1, and pathogenic mutations in CULLIN7 (CUL7 [MIM 609577]) were subsequently identified as the primary cause of 3-M syndrome.4–6 More recently, further autozygosity mapping revealed a second 3-M syndrome locus on chromosome 2q35-q36.1 with the underlying mutations identified in Obscurin-like 1 (OBSL1 [MIM 610991]).7,8 To date, there have been approximately 100 reported cases of 3-M syndrome.1–8

CUL7 acts as the structural component of an E3 ubiquitin ligase consisting of SKP1, ROC1, and FBXW8,9 as part of the proteasomal degradation pathway, whose targets include the growth factor signaling molecule IRS-1.10 Unlike other cullin proteins, CUL7 also has nonproteolytic functions, including interaction with the tumor suppressor p53; loss of CUL7 activity results in inhibition of p53-mediated cell-cycle progression.11,12 In contrast OBSL1 is highly homologous to the giant muscle protein Obscurin and has been identified as a cytoskeletal adaptor protein13 that interacts with the giant cytoskeletal proteins titin and myomesin.14 OBSL1 had not been recognized to have a role in growth. We previously demonstrated that loss of OBSL1 by siRNA knockdown leads to concomitant loss of CUL7 in an HEK293 model.7 Huber et al. established that individuals with 3-M syndrome and OBSL1 mutations showed significant modulation of Insulin-like growth factor binding protein 2 (IGFBP2 [MIM 146731]) and IGFBP5 (MIM 146734) expression.8 These findings suggested that both CUL7 and OBSL1 are likely to exist in a common pathway7 and that alterations in IGFBPs and hence changes in IGF levels may contribute to the pathogenesis of 3-M syndrome.8

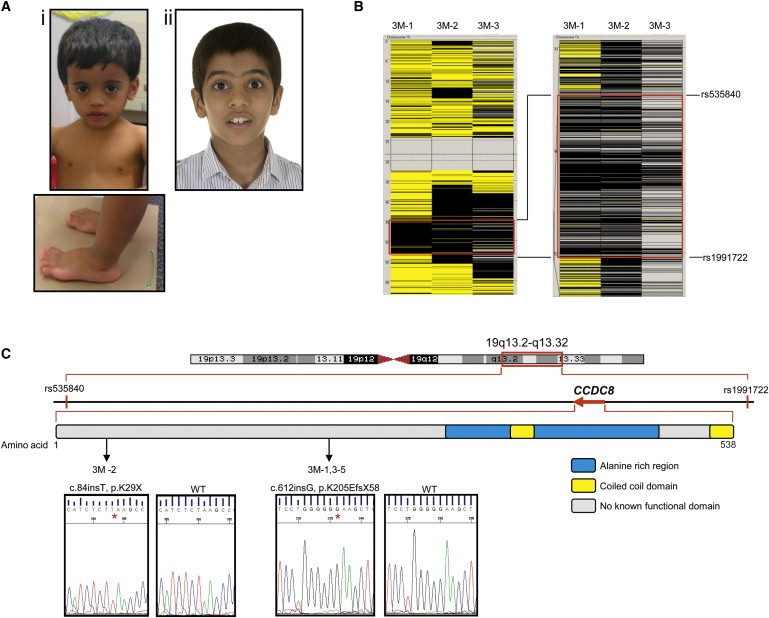

We identified individuals of South Asian descent who had 3-M syndrome and a history of consanguinity and did not carry CUL7 or OBSL1 mutations (Figure 1A and Table 1). With institutional ethical approval and informed consent, whole blood was collected from affected individuals and genomic DNA extracted via standard procedures. Autozygosity mapping on three such individuals, all unrelated (3M-1, 3M-2, and 3M-3), using the Affymetrix Genome-Wide Human SNP Array 6.0, and analysis of SNP genotype data by the AutoSNPa program15 revealed a potential third 3-M syndrome locus located on chromosome 19q13.2-q13.32. The autozygous region of 7.9 Mb is flanked by recombinant SNPs rs535840 (45,373,227 bp) and rs1991722 (53,270,701 bp) (Figure 1B) and contains 301 protein-coding genes. Exome sequencing capture with the Agilent SureSelect in-solution target enrichment system using the ABI SOLiD 4.0 platform was performed in all three individuals. Filtering of sequence data from the autozygous region against dbSNP, HapMap, and previously generated in-house data identified two different homozygous duplication variants in individuals 3M-1 and 3M-2 in CCDC8, coiled-coil domain containing protein 8 (Ensembl: ENSG00000169515, RefSeq: NM_032040.3, GenBank: NC_000019.9). Low sequence coverage for CCDC8 in 3M-3 prevented identification of a mutation in this person (Figure S1 available online). Previously unidentified variants within the homozygous 19q13.2-q13.32 region were also identified. However, these were not found in multiple individuals or not considered to be pathogenic (Table S1).

Figure 1.

Mutations in CCDC8 Cause 3-M Syndrome

(A) Individuals with 3-M syndrome who have CCDC8 mutations: i) 3M-2, ii) 3M-5. Their phenotype is indistinguishable from individuals with CUL7 or OBSL1 mutations.

(B) Region of homozygosity on chromosome 19 common to three affected consanguineous individuals from different families. Analysis of SNP data from the Affymetrix Genome-Wide Human SNP Array 6.0 was performed by AutoSNPa. Black and yellow bars indicate homozygous and heterozygous SNP calls, respectively. Isolated heterozygous SNP calls within the larger homozygous region are likely to correspond to missed calls. The region of common homozygosity is flanked by recombinants at rs535840 located at 45,373,227 bp and rs1991722 located at 53,270,701 bp, as shown by the red boxes.

(C) Schematic of the third 3-M syndrome critical region and identity of CCDC8 mutations. Shown is a genetic map of chromosome 19 highlighting the critical region located between rs535840 and rs1991722 and the relative location of CCDC8 within the region. CCDC8 is a single-exon gene encoding a protein of 538 amino acids, and bioinformatic analysis has indicated a coiled-coil domain located between residues 349–369 and 513–535 and an alanine-rich domain located between residues 299 and 471. Location and chromatograms of mutations in CCDC8 in individuals with 3-M syndrome are indicated by arrows.

Table 1.

Clinical Findings of Individuals with 3-M Syndrome

|

3-M ID |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3M-1a | 3M-1b | 3M-2 | 3M-3 | 3M-4 | 3M-5 | |

| Clinical Features | ||||||

| Gender | M | M | F | F | M | M |

| Birth weight (g) | 2200 | 2500 | 2400 | 2100 | 900 | 2150 |

| Birth weight SD | −3 | −2.2 | −2.6 | −3.1 | −6.3 | −3.1 |

| Age at initial presentation (yrs) | 2.8 | 0.4 | 4 | 0.65 | 4.4 | 0.75 |

| Height SD at presentation | −3 | −3.5 | −3.3 | −6.7 | −4.8 | −3.4 |

| Weight SDat presentation | −3.9 | −4.1 | −4.3 | −3.7 | −5.2 | −3 |

| OFC SD at presentation | 0 | −0.9 | NA | −3.2 | NA | NA |

| Radiological Features | ||||||

| Tall vertebral bodies | − | − | − | + | − | + |

| Slender long bones | − | − | − | + | − | + |

| Facial Features | ||||||

| Fleshy tipped nose | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Anteverted nares | + | + | − | − | − | + |

| Full fleshy lips | − | − | + | + | − | − |

| Triangular face | + | − | + | + | − | + |

| Dolicocephaly | − | − | + | − | − | + |

| Frontal bossing | + | − | + | + | + | + |

| Midface hypoplasia | + | − | + | − | + | − |

| Long philtrum | − | − | − | − | + | − |

| Pointed chin | + | + | + | − | − | + |

| Prominent ears | + | − | − | − | + | + |

| Other Clinical Features | ||||||

| Short neck | + | + | − | − | + | − |

| Winged scapulae | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Square shoulders | + | + | − | − | − | + |

| Short thorax | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Transverse chest groove | + | + | − | − | − | − |

| Pectus deformity | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Hyperlordosis | − | − | + | − | − | + |

| Scoliosis | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Hypermobility of joints | − | − | + | − | − | − |

| Fifth-finger clinodactyly | − | − | − | − | − | + |

| Prominent heels | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Spina bifida occulta | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Developmental dysplasia hip | + | − | − | + | − | − |

NA, not available; OFC, occipitofrontal circumference; SD, standard deviation. Auxology, radiological features, and clinical phenotype of six 3-M syndrome persons with CCDC8 mutations. List of clinical features from Hanson et al.7

Sanger sequencing of CCDC8 confirmed the identity of the two variants and also identified mutations in an additional three families, including individual 3M-3. The mutations were not identified in 210 ethnically matched normal control chromosomes. 3M-2 was homozygous for c.84dup, predicting p.Lys29X, whereas 3M-1, 3M-3, 3M-4, and 3M-5 were all homozygous for c.612dup, predicting p.Lys205GlufsX59 (Figure 1C). SNP analysis revealed that individuals from families 3M-1 and 3M-3 shared a region of common haplotype surrounding the CCDC8 loci, suggesting that c.612insG is a possible founder mutation (Table S2). Both CCDC8 variants lead to the generation of a premature-termination codon. CCDC8 comprises a single exon, so neither variant would be expected to lead to nonsense-mediated decay; we predict that the mutations would generate truncated CCDC8 with subsequent loss of function. For further verification of both variants, the coding sequence of CCDC8 was analyzed in exome-sequencing data in a control set of 401 persons enrolled in the ClinSeq cohort.16 DNA was captured with the Agilent SureSelect system and sequenced as described.17 Both variants were absent from 401 control individuals in the ClinSeq cohort; however, four SNPs in CCDC8 were identified (Table S3). CCDC8 includes an alanine-rich domain and has several putative coiled-coil domains (Figure 1C). BLAST revealed that the N-terminal region of CCDC8 shares similarity to the N-terminal region of the Paraneoplastic Ma antigens (PNMA) family of proteins. Coiled coils have been identified in both transcription factors and structural cytoskeletal proteins. The function of CCDC8 has not been defined, but its association to 3-M syndrome indicates a key role in human growth.

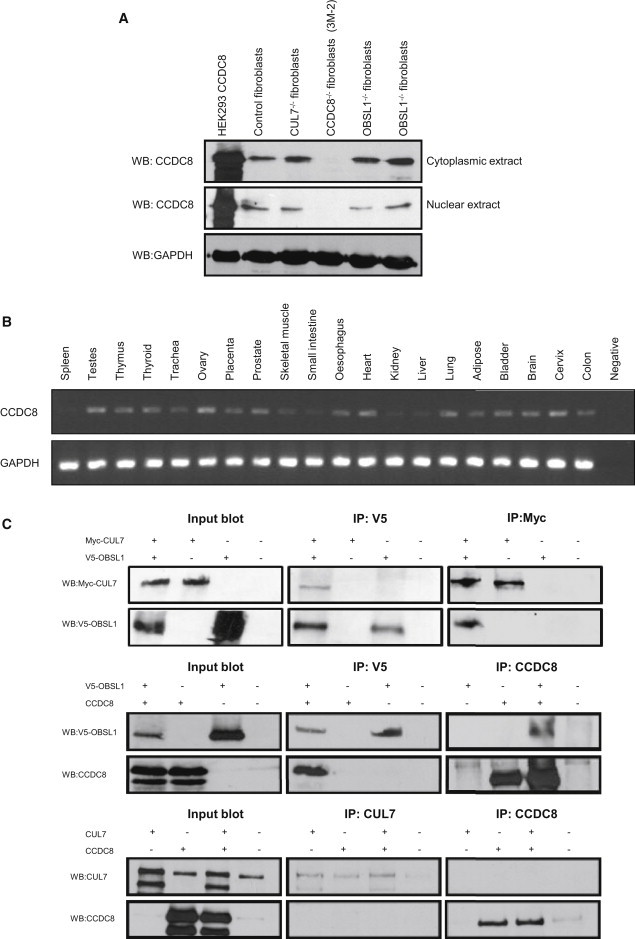

We generated a skin fibroblast cell line from individual 3M-2 and cultured it under standard conditions, and we demonstrated by immunoblotting that CCDC8 was not detectable. Both wild-type control fibroblasts, as well as those derived from individuals 3-M syndrome who had either CUL7 or OBSL1 mutations, had comparable levels of CCDC8 (Figure 2A). This suggests that CCDC8 mutations in individuals with 3-M syndrome are highly likely to be pathogenic and that loss of either CUL7 or OBSL1 does not significantly alter CCDC8 levels. We have also confirmed that a human CCDC8 exogenously expressed clone runs at the same molecular mass (∼90 kDa) as endogenous CCDC8 (Figure 2A). Bioinformatic analysis of CCDC8 reveals a number of posttranslational modification sites, including amidation, glycosylation, phosphorylation, and myristalation (data not shown), which may explain the shift in molecular mass from the expected 59 kDa.

Figure 2.

Molecular Characterization of CCDC8

(A) Immunoblot analysis of CCDC8 reveals loss of CCDC8 in an individual with 3-M syndrome and a CCDC8 mutation. HEK293 cells were transfected with a CCDC8 clone 24 hr before harvesting for both cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions. Human skin fibroblasts from controls and individuals with 3-M syndrome who have CUL7, OBSL1, or CCDC8 mutations were also harvested for cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions via standard protocols. Direct immunoblotting was performed for CCDC8 (Abnova) and loading was controlled by GAPDH (Santa-Cruz), demonstrating that individuals with 3-M syndrome who have either CUL7 or OBSL1 mutations have normal levels of CCDC8, whereas CCDC8 was undetectable in individual 3M-2.

(B) RT-PCR of CCDC8 and GAPDH in a variety of adult tissues. The FirstChoice Human Total RNA Survey Panel (Ambion) was used for assessing CCDC8 expression in 20 different human tissues; CCDC8 mRNA was expressed widely but with low levels in spleen, skeletal muscle, small intestine, kidney, and liver.

(C) Characterization of interactions among CUL7, OBSL1, and CCDC8. Immunoprecipitation analysis of the interactions between Myc-tagged CUL7 and V5-tagged OBSL1, V5-tagged OBSL1 and CCDC8, and CUL7 and CCDC8 in HEK293 cells. Plasmids expressing Myc-tagged CUL7, V5-tagged-OBSL1, and CCDC8 were used for transfection of HEK293 cells. The presence of recombinant proteins in each indicated transfection set was determined by direct immunoblot analysis of protein extracts. Interactions between Myc-tagged CUL7 and V5-tagged OBSL1, V5-tagged OBSL1 and CCDC8, and CUL7 and CCDC8 variants were analyzed by immunoprecipitation of extracts from each indicated transfection set with antibodies against V5 (AbDSerotec), c-Myc (Santa-Cruz), CUL7 (Santa-Cruz), or CCDC8 (Abnova), followed by capture with magnetic Dynabeads (Invitrogen). The precipitates were analyzed by immunoblotting with specific antibodies.

RT-PCR analysis detected CCDC8 expression in a wide range of human adult tissues but with low expression in spleen, skeletal muscle, small intestine, kidney, and liver (Figure 2B). Analysis of gene expression data using the UCLA Gene Expression Tool (UGET)18 and a publicly available resource of Affymetrix microarray data sets (Celsius)19 shows a strong correlation between both CUL7 and OBSL1 expression and CCDC8 expression (data not shown).

To investigate the physical associations of CUL7, OBSL1, and CCDC8, coimmunoprecipitation assays were performed. We cotransfected CUL7 with OBSL1, CUL7 with CCDC8, and OBSL1 with CCDC8, overexpressing plasmid constructs into HEK293 cells. Using this technique, we found that Myc-CUL7 was recovered from immunoprecipitates of coexpressed V5-OBSL1. We also established that CCDC8 was recovered from immunoprecipitates of coexpressed V5-OBSL1. We further confirmed these interactions by using immunoprecipitates of Myc-CUL7 and CCDC8. These data suggest that CUL7 and OBSL1 are physically associated in vitro while at the same time determining that OBSL1 and CCDC8 also interact. However CUL7 and CCDC8 do not interact in this system (Figure 2C).

Our identification of mutations in CCDC8 as a cause of 3-M syndrome broadens the hypothesis that 3-M syndrome is a disorder of a common growth pathway comprising at least CUL7, OBSL1, and CCDC8. The interaction studies suggest that OBSL1 may act as the adaptor protein linking CUL7 and CCDC8, and indeed, this is consistent with its previously postulated function. Previously, Geisler et al.13 showed that OBSL1 originates from a genomic duplication and rearrangement of obscurin prior to the evolution of teleost zebrafish. On the other hand, CUL7 and its closely related homolog CUL9 are found as a single gene in Xenopus tropicalis, a probable duplication event giving rise to separate genes for CUL7 and CUL9 in higher vertebrates. CCDC8 is also only present in placental mammals. We propose that CUL7, OBSL1, and CCDC8 are vital to the control of mammalian growth.

Acknowledgments

We thank all healthcare professionals contributing to the care of families described here. Support from the National Institute of Health Research Manchester Biomedical Research Centre is acknowledged. P.G.M. is a Medical Research Council (UK) Clinical Research Fellow. The NISC Comparative Sequencing Program and the ClinSeq study are funded by the National Human Genome Research Institute of the NIH.

Supplemental Data

Web Resources

The URLs for data presented herein are as follows:

AutoSNPa, http://dna.leeds.ac.uk/autosnpa/

Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST), http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi

HapMap, http://hapmap.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/

Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man, http://www.omim.org

UCLA Gene Expression Tool, http://genome.ucla.edu/∼jdong/GeneCorr.html

University of California Santa Cruz Human Genome Browser, http://genome.cse.ucsc.edu/cgi-bin/hgGateway

References

- 1.Miller J.D., McKusick V.A., Malvaux P., Temtamy S., Salinas C. The 3-M syndrome: a heritable low birthweight dwarfism. Birth Defects Orig. Artic. Ser. 1975;11:39–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van der Wal G., Otten B.J., Brunner H.G., van der Burgt I. 3-M syndrome: description of six new patients with review of the literature. Clin. Dysmorphol. 2001;10:241–252. doi: 10.1097/00019605-200110000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Temtamy S.A., Aglan M.S., Ashour A.M., Ramzy M.I., Hosny L.A., Mostafa M.I. 3-M syndrome: a report of three Egyptian cases with review of the literature. Clin. Dysmorphol. 2006;15:55–64. doi: 10.1097/01.mcd.0000198926.01706.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huber C., Dias-Santagata D., Glaser A., O'Sullivan J., Brauner R., Wu K., Xu X., Pearce K., Wang R., Uzielli M.L. Identification of mutations in CUL7 in 3-M syndrome. Nat. Genet. 2005;37:1119–1124. doi: 10.1038/ng1628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maksimova N., Hara K., Miyashia A., Nikolaeva I., Shiga A., Nogovicina A., Sukhomyasova A., Argunov V., Shvedova A., Ikeuchi T. Clinical, molecular and histopathological features of short stature syndrome with novel CUL7 mutation in Yakuts: new population isolate in Asia. J. Med. Genet. 2007;44:772–778. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2007.051979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huber C., Delezoide A.L., Guimiot F., Baumann C., Malan V., Le Merrer M., Da Silva D.B., Bonneau D., Chatelain P., Chu C. A large-scale mutation search reveals genetic heterogeneity in 3M syndrome. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2009;17:395–400. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2008.200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hanson D., Murray P.G., Sud A., Temtamy S.A., Aglan M., Superti-Furga A., Holder S.E., Urquhart J., Hilton E., Manson F.D. The primordial growth disorder 3-M syndrome connects ubiquitination to the cytoskeletal adaptor OBSL1. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2009;84:801–806. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huber C., Fradin M., Edouard T., Le Merrer M., Alanay Y., Da Silva D.B., David A., Hamamy H., van Hest L., Lund A.M. OBSL1 mutations in 3-M syndrome are associated with a modulation of IGFBP2 and IGFBP5 expression levels. Hum. Mutat. 2010;31:20–26. doi: 10.1002/humu.21150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dias D.C., Dolios G., Wang R., Pan Z.Q. CUL7: A DOC domain-containing cullin selectively binds Skp1.Fbx29 to form an SCF-like complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:16601–16606. doi: 10.1073/pnas.252646399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xu X., Sarikas A., Dias-Santagata D.C., Dolios G., Lafontant P.J., Tsai S.C., Zhu W., Nakajima H., Nakajima H.O., Field L.J. The CUL7 E3 ubiquitin ligase targets insulin receptor substrate 1 for ubiquitin-dependent degradation. Mol. Cell. 2008;30:403–414. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaustov L., Lukin J., Lemak A., Duan S., Ho M., Doherty R., Penn L.Z., Arrowsmith C.H. The conserved CPH domains of Cul7 and PARC are protein-protein interaction modules that bind the tetramerization domain of p53. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:11300–11307. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611297200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jung P., Verdoodt B., Bailey A., Yates J.R., 3rd, Menssen A., Hermeking H. Induction of cullin 7 by DNA damage attenuates p53 function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:11388–11393. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609467104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Geisler S.B., Robinson D., Hauringa M., Raeker M.O., Borisov A.B., Westfall M.V., Russell M.W. Obscurin-like 1, OBSL1, is a novel cytoskeletal protein related to obscurin. Genomics. 2007;89:521–531. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2006.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fukuzawa A., Lange S., Holt M., Vihola A., Carmignac V., Ferreiro A., Udd B., Gautel M.J. Interactions with titin and myomesin target obscurin and obscurin-like 1 to the M-band: implications for hereditary myopathies. J. Cell Sci. 2008;121:1841–1851. doi: 10.1242/jcs.028019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carr I.M., Flintoff K.J., Taylor G.R., Markham A.F., Bonthron D.T. Interactive visual analysis of SNP data for rapid autozygosity mapping in consanguineous families. Hum. Mutat. 2006;27:1041–1046. doi: 10.1002/humu.20383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Biesecker L.G., Mullikin J.C., Facio F.M., Turner C., Cherukuri P.F., Blakesley R.W., Bouffard G.G., Chines P.S., Cruz P., Hansen N.F., NISC Comparative Sequencing Program The ClinSeq Project: piloting large-scale genome sequencing for research in genomic medicine. Genome Res. 2009;19:1665–1674. doi: 10.1101/gr.092841.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Teer J.K., Bonnycastle L.L., Chines P.S., Hansen N.F., Aoyama N., Swift A.J., Abaan H.O., Albert T.J., Margulies E.H., Green E.D., NISC Comparative Sequencing Program Systematic comparison of three genomic enrichment methods for massively parallel DNA sequencing. Genome Res. 2010;20:1420–1431. doi: 10.1101/gr.106716.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Day A., Dong J., Funari V.A., Harry B., Strom S.P., Cohn D.H., Nelson S.F. Disease gene characterization through large-scale co-expression analysis. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e8491. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Day A., Carlson M.R., Dong J., O'Connor B.D., Nelson S.F. Celsius: a community resource for Affymetrix microarray data. Genome Biol. 2007;8:R112. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-6-r112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.