Abstract

Chronic lung colonization with Pseudomonas aeruginosa is anticipated in cystic fibrosis (CF). Abnormal terminal glycosylation has been implicated as a candidate for this condition. We previously reported a down-regulation of mannose-6-phosphate isomerase (MPI) for core N-glycan production in the CFTR-defective human cell line (IB3). We found a 40% decrease in N-glycosylation of IB3 cells compared with CFTR-corrected human cell line (S9), along with a threefold-lower surface attachment of P. aeruginosa strain, PAO1. There was a twofold increase in intracellular bacteria in S9 cells compared with IB3 cells. After a 4-hour clearance period, intracellular bacteria in IB3 cells increased twofold. Comparatively, a twofold decrease in intracellular bacteria occurred in S9 cells. Gene augmentation in IB3 cells with hMPI or hCFTR reversed these IB3 deficiencies. Mannose-6-phosphate can be produced from external mannose independent of MPI, and correction in the IB3 clearance deficiencies was observed when cultured in mannose-rich medium. An in vivo model for P. aeruginosa colonization in the upper airways revealed an increased bacterial burden in the trachea and oropharynx of nontherapeutic CF mice compared with mice treated either with an intratracheal delivery adeno-associated viral vector 5 expressing murine MPI, or a hypermannose water diet. Finally, a modest lung inflammatory response was observed in CF mice, and was partially corrected by both treatments. Augmenting N-glycosylation to attenuate colonization of P. aeruginosa in CF airways reveals a new therapeutic avenue for a hallmark disease condition in CF.

Keywords: bacterial clearance, cystic fibrosis, gene therapy, N-glycosylation

CLINICAL RELEVANCE.

This work brings to light a potential novel therapeutic option for treating bacterial colonization in the airways of cystic fibrosis patients.

The cystic fibrosis (CF) lung environment has a predilection for the opportunistic pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Most patients with CF develop a persistent colonization with P. aeruginosa (1, 2). This chronic lung infection causes an influx of cellular infiltrates that leads to airway obstruction and the destruction of lung tissue, and possibly respiratory failure (3–5). The life expectancy of patients with CF has increased thanks to treatments for these symptoms; still, a high incidence of premature death occurs. Therefore, there is a constant effort to develop novel therapies to improve the lives of infected patients with CF. CF lung deficiencies in bacterial clearance have been the focus of many efforts to clear microorganisms from airways (6, 7). Although the primary focus of chronic lung infection has been mucociliary dysfunction (7–10), other studies have revealed a breech in the innate immune response, abnormal glycosylation, and deficiencies in bacterial ingestion and clearance by airway epithelial cells (2, 9, 11–14).

Abnormal glycosylation within the airways is a common CF phenotype (15–18). Unfortunately, the consequences of abnormal glycosylation are still unclear, and have hindered the development of a definitive explanation. Although several P. aeruginosa receptors have been targeted as candidates for increased P. aeruginosa in the CF airway, disparity and controversy has emerged. Investigators have demonstrated an increase in binding of P. aeruginosa to CF airway epithelium from higher levels of GalNAcβ1–4Gal asialo-GM1 bacterial receptors (12, 18–20). Alternatively, others have reported that the CFTR protein binds and coordinates ingestion of P. aeruginosa (11, 21–23). In addition, others have revealed a reduced activity of acid sphingomyelinase (ASMase) and abnormal glycosylation within lipid rafts contributing to the clearance deficiency (24, 25). Given the numerous, diverse observations, it remains plausible that the reason for this severe pathology is not a mutually exclusive event, and that other candidates have not been included.

Core N-glycosylation deficiency is an alternative candidate being explored. A previous study revealed a decrease in mannose-6-phosphate isomerase (MPI) gene expression in cultured CF epithelial cells (26). In addition, a carbohydrate-deficient transferrin increase, which results from a defect in N-glycosylation, has been revealed in patients with CF (27). Carbohydrate-deficient transferrin increase has also been reported in the human glycosylation disorder 1b (28), which is linked to a homozygous defect in the MPI gene. As an alternative to MPI gene augmentation, mannose-6-phosphate can be supplemented by direct phosphorylation of external mannose by hexokinase (29).

We decided to explore N-glycosylation on the surface of airway epithelial cells as a candidate for CF clearance abnormality. Although this study does not focus on a specific host receptor, the data presented in this article suggest that core N-glycosylation augmentation by MPI correction or hypermannose treatment improves bacterial attachment, ingestion, and clearance. In vivo studies were performed using a Pseudomonas-infected CF mouse model in which the susceptibility to bacterial colonization is CFTR dependent (30). This model was used to assess a potential clearance deficiency in CFTR-deficient mice, and to determine the feasibility of correction using MPI gene augmentation or a hypermannose diet.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

See the online supplemental for complete details.

Cell Lines

IB3 cells originated from a patient with CF, and S9 cells are derived from IB3 cells with a CFTR correction.

IB3 Cell Treatment

Plasmid transfection used a proviral overexpression cassette (31) with hMPI cDNA or functional Δ264 hCFTR mini-gene previously developed (32), pTR2-CB-hMPI and pTR2-CB-Δ264 hCFTR. Control plasmid was human survival motor neuron (SMN) cDNA not reported as abnormally regulated (26), pTR2-CB-SMN. Mannose treatment medium was 50 nM, 500 nM, 5 μM, 50 μM, 500 μM, or 5 mM mannose.

CFTR siRNA in S9 Cells

CFTR knockdown used a CFTR siRNA plasmid (33), pTR2-U6-CFTRsiRNA. siRNA sequence was 5-GGAUACAGACAGCGCCUGGdTdT-3 and 5-CCAGGCGCUGUCUGUAUCCdTdT-3, previously used by Singh and colleagues (34). The Ambion (Austin, TX, USA) siRNA control was used.

Bacteria

P. aeruginosa strain PAO1 and a PAO1-GFP fluorescent strain (35) were used in vitro. A mucoid P. aeruginosa strain (36) was used in vivo.

In Vitro Membrane Glycosylation Profiling

FITC-conjugated lectins, concanavalin A (ConA) and lens culinaris lectin (LcH) for N-glycosylation, and helix pomatia for N-acetylgalactosamine O-glycosylation, were used at 50 μg/ml followed by FACS analysis.

In Vitro Bacterial Binding

Procedures have been described previously (23). Infection media were PAO1 or mucoid strain (1 hr at 37°C). Host cell lysis buffer (50 mM tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, and 1% NP-40; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) was added to release bacteria, which was collected, diluted, cultured, and then grown overnight and counted.

In Vitro Bacterial Ingestion

The PAO1-GFP strain was used to infect host cells followed by FACS. The initial steps mimic in vitro binding followed by a gentamicin treatment to kill extracellular bacteria.

In Vitro Bacterial Clearance and Host Cell Death

Clearance and host cell death analysis mimic ingestion analysis with additions. After gentamicin treatment, host cells were incubated for 4 hours (clearance period). After clearance, host cells were stained with 7AAD (BD Sciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ) for host cell death analysis. Dual-stain FACS analysis was performed.

FACS Analysis

FITC-conjugated lectins, PAO1-GFP fluorescence, and 7AAD analysis used a BD FACScalibur flow cytometer. For dual staining, GFP+ cells were gated and 7AAD staining was analyzed within GFP+ cells.

Mouse Model

Cftrtm1Unc-TgFABP-CFTR mice were used (37). The infection model was modified from a drinking water challenge previously developed (30). AAV vectors included AAV5-CB-GFP or AAV5-CB-mMPI. Vectors were delivered to the trachea (38) 2 weeks before infection. Hypermannose-treated mice were given 5 mg/ml mannose or glucose in drinking water for 4 weeks before infection.

Analysis of In Vivo Bacterial Load

Bacterial load was tracked by weekly oropharynx swabs. After diluting swabs, overnight growth occurred. Colonies were transferred to filter paper, and P. aeruginosa colonies were screened with Gaby-Hadley reagents (Sigma).

RESULTS

N-Glycosylation Deficiency in IB3 Cells

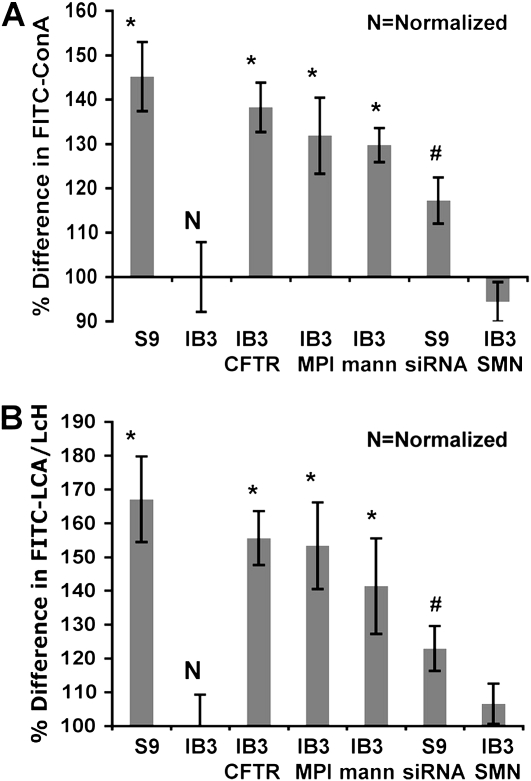

Profiling core surface N-glycosylation was analyzed to determine the effects of MPI transcript deficiency previously observed in IB3 cells. ConA and LcH were used to measure levels of N-glycosylation residues. Although ConA also binds α-mannosidic structure, it is widely used in measuring high-mannose, hybrid, and biantennary complex N-glycans, and is also used in N-glycan affinity chromatography (39–41). In addition, ConA is not known to measure O-linked glycans (42). ConA showed a 50% increase in S9 cells compared with IB3 cells, which was then reduced by CFTR siRNA treatment of S9 cells (Figures 1A and 1B). Similar results were revealed when using the LcH lectin instead of ConA, which attaches to the fucosylated core region of bi- and triantennary complex N-glycans (41, 42). This demonstrates that an N-glycosylation deficiency can be linked to a CFTR defect. Successful correction occurred by gene augmentation of hMPI in IB3 cells, achieving a 40% increase in N-glycosylation. The results were similar to CFTR correction. Growing IB3 cells in hypermannose media also significantly increased N-glycosylation. No significant difference in O-linked glycosylation between IB3 and S9 cells was observed using the helix pomatia lectin (data not shown) (41–43).

Figure 1.

Percent difference of attached FITC-conjugated lectins, lens culinaris lectin (LcH) and concanavalin A (ConA) normalized to IB3 cells. IB3 treatments included pTR2-CB-Δ264 hCFTR, pTR2-CB-hMPI, pTR2-CB-SMN (control), or hypermannose media at 500-μM concentration and S9 cells treated with pTR2-U6-CFTRsiRNA or siRNA negative control. (A) Data collected from FITC-ConA and (B) data collected using FITC–LCA/LcH. Statistical analysis was done using a two-tailed, paired t test (*P < 0.05 analyzed against IB3; #P < 0.05 analyzed against S9). Data were collected from three separate trials.

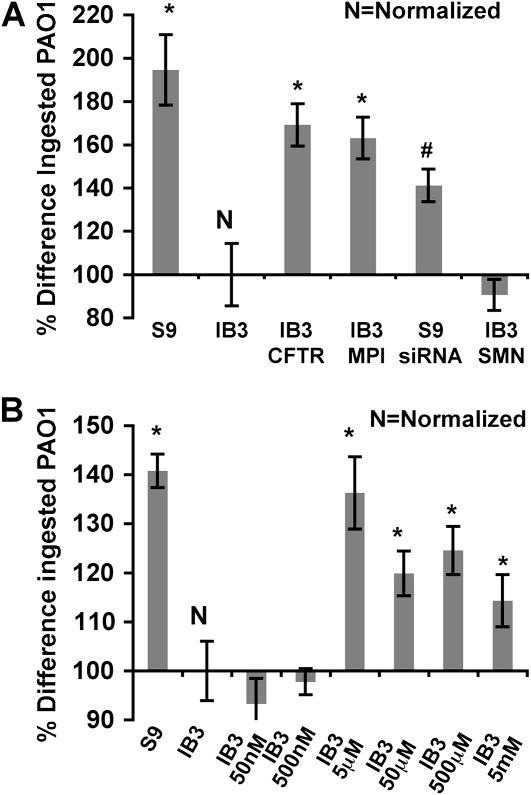

Bacterial Ingestion Deficiency In Vitro

We observed a cftr-dependent bacterial attachment deficiency that was corrected with MPI gene augmentation and mannose treatment (see the online supplement), and assessed the consequences in bacterial ingestion. S9 cells showed twofold-higher intracellular PAO1-GFP when compared with IB3 cells. Furthermore, CFTR silencing in S9 cells reduced ingestion, with bacterial loads reflecting the results in IB3 cells (Figure 2A). This reduced bacterial ingestion phenotype in IB3 cells was complemented by gene augmentation using pTR2-CB-hMPI or pTR2-CB-Δ264 hCFTR, which achieved an 80% increase of intracellular bacteria (Figure 2A). In addition, mannose-rich medium resulted in a maximum of 30% increase at 5-μM concentration (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Difference in percentage of green fluorescent protein (GFP) fluorescence of host cells due to internalized GFP plus PAO1 strain shown as a percentage change compared with untreated IB3 cells. GFP fluorescence from ingested PAO1-GFP was detected by FACS analysis. (A) IB3 cells were treated with pTR2-CB-Δ264 hCFTR, pTR2-CB-hMPI, or pTR2-CB-SMN (control), and S9 cells were treated with pTR2-U6-CFTRsiRNA or siRNA negative control. (B) IB3 cells were treated with the indicated amount of mannose. Statistical analysis was done using a two-tailed, paired t test (*P < 0.05 analyzed against IB3; #P < 0.05 analyzed against S9). Data were collected from three separate trials.

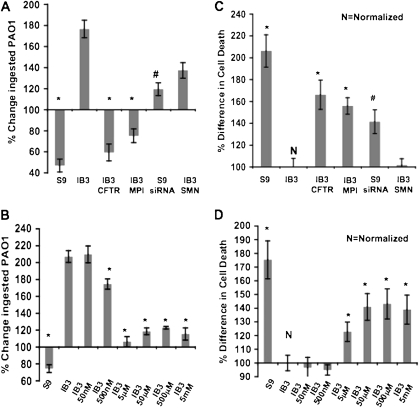

Bacterial Clearance and Cell Death Deficiency

The ability of these IB3 cells to clear intracellular PAO1 adequately was tested. In IB3 cells, the amount of intracellular bacteria doubled after a 4-hour clearance period. Conversely, intracellular bacteria after the same clearance period was reduced to one-half in the S9 cells. CFTR gene knockdown in S9 cells reversed this clearance, which conferred an IB3-like phenotype. Furthermore, hMPI or hCFTR gene correction resulted in improved clearance (Figure 3A). From mannose treatment, intracellular PAO1-GFP at 5 μM mannose remained unchanged after clearance. At all other mannose concentrations, except 50 nM and 500 mM, there was only a marginal increase compared with the twofold increase seen in untreated IB3 cells (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Change of intracellular PAO1-GFP from host cells after a 4-hour clearance period compared with initial internalized bacterial levels after infection, ingestion, and gentamicin treatment to kill extracellular PAO1-GFP, and the difference in host cell death from treated and untreated host cells after the same clearance period. (A and C) IB3 cells were treated with pTR2-CB-Δ264 hCFTR, pTR2-CB-hMPI, or pTR2-CB-SMN (control), and S9 cells were treated with pTR2-U6-CFTRsiRNA or siRNA negative control. (B and D) IB3 cells were cultured in indicated concentrations of mannose rich media. Statistical analysis was done using a two-tailed, paired t test (*P < 0.05 analyzed against IB3; #P < 0.05 analyzed against S9). Data were collected from three separate trials.

In vitro host cell death as a method for clearance was analyzed in the IB3 cells. There was a twofold increase in cell death using S9 cells compared with IB3 cells, and S9 CFTR siRNA reduced the cell death response after the clearance period. This IB3 deficiency was corrected by hMPI or hCFTR gene transfer, resulting in a 50% increase in cell death (Figure 3C). Culturing IB3 cells in mannose-rich medium revealed variable correction of the cell death defect, which peaked at 50 and 500 μM (Figure 3D).

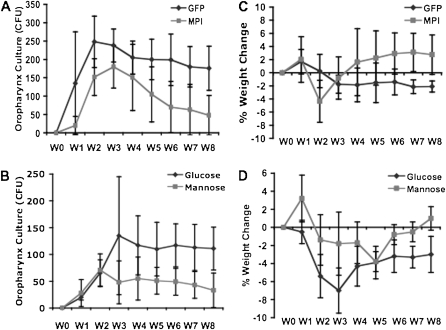

Tracking Bacterial Load in CFTR-Deficient Mouse Airways

A mucoid strain isolated from a patient with CF (36) was used to infect the airways of CF mice. The aggregation property of mucoid strains can potentially improve the chances of establishing colonization (44). The persistence of this bacterial infection was tracked during the infection period and for 6 weeks afterward. In both nontherapeutic groups (AAV5-GFP or hyperglucose) of CF mice, the bacterial infection in the upper airway persisted for the length of the study. Comparatively, in treated mice (AAV5-MPI or hypermannose), an acute infection occurred for the first 2 weeks, but then dissipated to nearly undetectable levels (Figures 4A and 4B).

Figure 4.

Total mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa CFU collected from weekly oropharynx culture swabs from cftr mice that were infected for 2 weeks with the mucoid strain via drinking water and treated with (A) AAV5-CB-mMPI viral vector, with AAV5-CB-GFP as control (n = 6) or (B) hypermannose diet of 5 mg/ml in drinking water with hyperglucose diet as control (n = 4). Weekly percentage changes in weight compared with Week 0 weight of infected mice treated with (C) AAV5-CB-mMPI, with AAV5-CB-GFP as a control (n = 6), or (D) hypermannose diet of 5 mg/ml in drinking water with hyperglucose diet as a control (n = 4). P < 0.05 using one-way ANOVA for repeat sampling between groups.

Tracking the Health of Mice after Bacterial Exposure

The systemic effects of the bacterial infection in the Cftrtm1Unc-TgFABP-CFTR mice were tracked by monitoring the weight of the mice. In all groups (treated and controls), there was an acute weight loss during infection. Although all groups showed a significant improvement in weight lost during the 6 weeks after the infection, only the treatment groups (AAV5-MPI and hypermannose) had an overall increase in weight. Conversely, the nontherapeutic mice still had significant weight loss at the end of the study (Figures 4C and 4D).

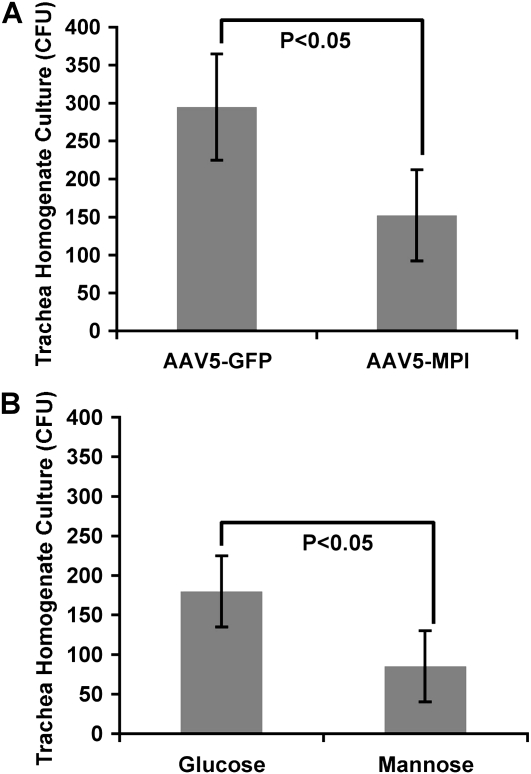

Measuring Bacterial Load in Trachea and Lungs

Bacterial load was measured in trachea homogenates and in lung homogenates. There was a twofold increase in bacterial load in the trachea from the nontherapeutic CF mice (AAV5-GFP or hyperglucose) compared with their respective treatment groups (AAV5-mMPI or hypermannose) (Figure 5). In addition, 70% of the lung homogenates from nontherapeutic mice had detectable levels of P. aeruginosa compared with 30% in treated mice (data not shown).

Figure 5.

Cultured CFU from trachea homogenates of cftr mice infected with mucoid strain and treated with (A) AAV5-CB-mMPI viral vector, with AAV5-CB-GFP as a nontherapeutic control (n = 6) or (B) hypermannose diet of 5 mg/ml in drinking water, with hyperglucose diet as a non-therapeutic control (n = 4). Statistical analysis was done using a two-tailed, paired t test.

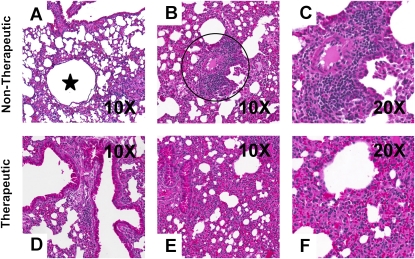

Lung Pathology

Persistent bacterial infection in the CF lung results in chronic inflammation. The observations depicted in Figure 6 demonstrate an increase in multifocal, moderate inflammation, with more cases of bronchiectasis in nontherapeutic mice compared with the treatment groups. In addition, 50% of the treated mice presented with no lung inflammation compared with only 20% in the nontherapeutic mice (Table 1).

Figure 6.

Images of inflammatory conditions revealed by hematoxylin and eosin staining of lung sections from cftr mice infected for 2 weeks with the mucoid strain through the drinking water. Shown are cases, in nontherapeutic mice, of (A) bronchiectasis (star) and (B and C) multifocal, moderate inflammation (within circle [B]) and, in therapeutic mice, (D) healthy airways and (E and F) noninflammatory conditions.

TABLE 1.

INFLAMMATION SCORES FROM LUNG SECTIONS OF INFECTED WHITSETT MICE

| AAV5-mMPI Treated (%) |

Mannose Treated (%) |

AAV5-GFP Control (%) |

Glucose Control (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bronchiectasis | 17 | 0 | 33 | 25 |

| None (0) | 50 | 50 | 17 | 25 |

| Mild focal (1) | 34 | 25 | 33 | 25 |

| Moderate multifocal (2) | 17 | 25 | 50 | 50 |

| Severe multifocal (3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Necrotic (4) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Definition of abbreviations: AAV, adeno-associated virus; GFP, green fluorescent protein; MPI, mannose-6-phosphate isomerase.

Data from a pathology report submitted by a trained pathologist who ranked the severity of inflammation from lung sections with H&E staining in a blinded fashion.

DISCUSSION

Previous studies have been successful in improving bacterial clearance in the CF airway, yet it is still unclear why P. aeruginosa plagues the CF airway. In addition, efforts to pinpoint the glycosylation phenotypes linked to deficient clearance of this pathogen have not yielded a clear understanding of this condition.

This study did not focus on a specific host receptor. Still, efforts to identify a host receptor, which may be altered in CF, have been made. Although some have reported the bacterial receptor asialo-GM1 glycosylation residue as a contributor to the increased P. aeruginosa (12, 19), disparate evidence has suggested otherwise (45). Moreover, this would not explain how P. aeruginosa supplants Staphylococcus aureus in patients with CF given that S. aureus has shown higher affinity to asialo-GM1 (46). The CFTR protein has also emerged as a potential receptor for P. aeruginosa binding directly to the airway epithelial cells (11, 21, 47) and subsequent internalization. Our ability to enhance bacterial clearance in IB3 cells independent of cftr correction with MPI gene augmentation or a mannose treatment would suggest that this corrective effect does not include attachment to the CFTR protein.

Yu and colleagues (24) showed that reduced ASMase activity in IB3 cells decreased internalized P. aeruginosa. In addition, IB3 cells presented with a decreased apoptosis response. This deficiency in bacterial clearance by internalization and host cell death can be corrected, not only by CFTR correction, but also by treatment with bacterial sphingomyelinase from S. aureus. ASMase deficiency is associated with a severe defect in functional ASMase. Site-directed mutagenesis of ASMase demonstrated that the development of mature ASMase protein was hindered by the removal of N-glycosylation sites (48). Taken together, these studies suggest that N-glycosylation abnormalities on ASMase in CF epithelial cells deficient in MPI expression could contribute to the bacterial clearance deficiency.

Our in vitro data has revealed that there is a strong correlation between the N-glycosylation deficiency in IB3 cells and improvement in bacterial ingestion and clearance by host cellular death. These IB3 deficiencies in bacterial binding, bacterial ingestion, bacterial clearance, and host cellular death can be partially corrected by treatment with pTR2-CB-MPI, or by growing CFTR-deficient host cells in mannose-rich media, both of which increased the levels of N-glycosylation residues on the surface of IB3 cells. It should be mentioned that this response was not strain specific, because the mucoid strain showed similar results to the PAO1 strain (data not shown).

The in vivo methods were complicated by the absence of robust colonization in CF mice. Infecting Cftrtm1Unc-TgFABP-CFTR mice with bacteria-tainted water established only a modest upper airway infection. This cftr-dependent upper airway colonization was achieved through the use of a P. aeruginosa mucoid strain; therefore, we are unable to suggest that this infection can be achieved using alternative strains. Still, it should be mentioned that Coleman and colleagues (30) demonstrated a range of success using different P. aureginosa strains with mucoid and nonmucoid characteristics. CFTR gene transfer was precluded from the in vivo studies, because the overall goal of the study was to demonstrate that N-glycan augmentation improves bacterial clearance independent of CFTR correction.

Unfortunately, the results from the mouse model study were not as profound as those from the in vitro study. Nevertheless, a significant increase in bacterial load occurred in the upper airway of untreated mice, along with significant weight loss compared with MPI gene augmentation or the noninvasive high-mannose diet. To date, no CFTR-deficient mouse model has been ideal for developing a chronic infection. Therefore, any potential therapeutic benefit that can be achieved from proposed treatments will unlikely be dramatic unless a more severe CFTR-defective mouse phenotype can be established.

Finally, we cannot completely rule out the possibility that the mannose receptor is involved in the in vivo corrective response. Mannose receptors contain an N-glycan–rich domain (49), and efforts to correct N-glycosylation deficiency can potentially influence the innate immune response to the P. aeruginosa challenge. Typically, rAAV transduction of monocytes in vivo is negligible, except for AAV5. Therefore, AAV5 MPI gene augmentation for improved gene transfer to the lung epithelium could potentially impact mannose receptors on monocytes.

A potential role of MPI expression in bacterial clearance has been demonstrated. Nonetheless, efforts to pinpoint why MPI down-regulation occurs in IB3 cells, as well as investigating the effects on mucin secretions from IB3 cells via an air–liquid interface cell culture study, need to be explored. Even in the absence of such answers, MPI gene augmentation and a noninvasive hypermannose diet showed significant improvement in bacterial clearance and reduced levels of detrimental lung inflammation. Hypermannose diet is already used as a clinical treatment for the glycosylation disorder 1b caused by a homozygous mutation of MPI (29), and the data presented from this study demonstrate that N-glycan augmentation has therapeutic potential for the bacterial clearance deficiency in CF.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Niels Hoiby (University of Copenhagen, Denmark) provided the mucoid Pseudomonas isolate used in vivo. Roberto Kolter (Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA) provided the PAOI strain expressing GFP for FACS analysis of intracellular bacteria. Hudson Freeze at the Burnham Institute (La Jolla, CA) donated the mouse and human MPI antibodies.

This work was supported in part by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grant P01-HL051811.

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue's table of contents at www.atsjournals.org

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1165/rcmb.2009-0285OC on August 6, 2010

Author Disclosure: None of the authors has a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Gilligan PH. Microbiology of airway disease in patients with cystic fibrosis. Clin Microbiol Rev 1991;4:35–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pier GB. Role of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator in innate immunity to Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2000;97:8822–8828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dinwiddie R. Pathogenesis of lung disease in cystic fibrosis. Respiration 2000;67:3–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bals R, Weiner DJ, Wilson JM. The innate immune system in cystic fibrosis lung disease. J Clin Invest 1999;103:303–307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Welsh MJ, Smith AE. Cystic fibrosis. Sci Am 1995;273:52–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davies JC, Alton EW, Bush A. Cystic fibrosis. BMJ 2007;335:1255–1259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boucher RC. Airway surface dehydration in cystic fibrosis: pathogenesis and therapy. Annu Rev Med 2007;58:157–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davies JC. Pseudomonas aeruginosa in cystic fibrosis: pathogenesis and persistence. Paediatr Respir Rev 2002;3:128–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gomez MI, Prince A. Opportunistic infections in lung disease: Pseudomonas infections in cystic fibrosis. Curr Opin Pharmacol 2007;7:244–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baum GL. Enhancing mucociliary clearance. Chest 1996;110:876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pier GB, Grout M, Zaidi TS. Cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator is an epithelial cell receptor for clearance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa from the lung. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1997;94:12088–12093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bryan R, Kube D, Perez A, Davis P, Prince A. Overproduction of the CFTR R domain leads to increased levels of asialoGM1 and increased Pseudomonas aeruginosa binding by epithelial cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 1998;19:269–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reiniger N, Lee MM, Coleman FT, Ray C, Golan DE, Pier GB. Resistance to Pseudomonas aeruginosa chronic lung infection requires cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator–modulated interleukin-1 (IL-1) release and signaling through the IL-1 receptor. Infect Immun 2007;75:1598–1608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Muir A, Soong G, Sokol S, Reddy B, Gomez MI, Van Heeckeren A, Prince A. Toll-like receptors in normal and cystic fibrosis airway epithelial cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2004;30:777–783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scanlin TF, Glick MC. Terminal glycosylation in cystic fibrosis. Biochim Biophys Acta 1999;1455:241–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rhim AD, Stoykova LI, Trindade AJ, Glick MC, Scanlin TF. Altered terminal glycosylation and the pathophysiology of cf lung disease. J Cyst Fibros 2004;3:95–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roussel P. Airway glycoconjugates and cystic fibrosis. Glycoconj J 2001;18:645–647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kube D, Adams L, Perez A, Davis PB. Terminal sialylation is altered in airway cells with impaired CFTR-mediated chloride transport. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2001;280:L482–L492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Imundo L, Barasch J, Prince A, Al-Awqati Q. Cystic fibrosis epithelial cells have a receptor for pathogenic bacteria on their apical surface. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1995;92:3019–3023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saiman L, Prince A. Pseudomonas aeruginosa pili bind to asialoGM1 which is increased on the surface of cystic fibrosis epithelial cells. J Clin Invest 1993;92:1875–1880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pier GB, Grout M, Zaidi TS, Olsen JC, Johnson LG, Yankaskas JR, Goldberg JB. Role of mutant CFTR in hypersusceptibility of cystic fibrosis patients to lung infections. Science 1996;271:64–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pier GB, Grout M, Zaidi TS, Goldberg JB. How mutant CFTR may contribute to Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection in cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1996;154:S175–S182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cannon CL, Kowalski MP, Stopak KS, Pier GB. Pseudomonas aeruginosa–induced apoptosis is defective in respiratory epithelial cells expressing mutant cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2003;29:188–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yu H, Zeidan YH, Wu BX, Jenkins RW, Flotte TR, Hannun YA, Virella-Lowell I. Defective acid sphingomyelinase pathway with Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection in cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2009;41:367–375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bajmoczi M, Gadjeva M, Alper SL, Pier GB, Golan DE. Cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator and caveolin-1 regulate epithelial cell internalization of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2009;297:C263–C277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Virella-Lowell I, Herlihy JD, Liu B, Lopez C, Cruz P, Muller C, Baker HV, Flotte TR. Effects of CFTR, interleukin-10, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa on gene expression profiles in a CF bronchial epithelial cell line. Mol Ther 2004;10:562–573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Larsson A, Flodin M, Kollberg H. Increased serum concentrations of carbohydrate-deficient transferrin (CDT) in patients with cystic fibrosis. Ups J Med Sci 1998;103:231–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kjaergaard S. Congenital disorders of glycosylation type IA and IB: genetic, biochemical and clinical studies. Dan Med Bull 2004;51:350–363. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Westphal V, Kjaergaard S, Davis JA, Peterson SM, Skovby F, Freeze HH. Genetic and metabolic analysis of the first adult with congenital disorder of glycosylation type IB: long-term outcome and effects of mannose supplementation. Mol Genet Metab 2001;73:77–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Coleman FT, Mueschenborn S, Meluleni G, Ray C, Carey VJ, Vargas SO, Cannon CL, Ausubel FM, Pier GB. Hypersusceptibility of cystic fibrosis mice to chronic Pseudomonas aeruginosa oropharyngeal colonization and lung infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2003;100:1949–1954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Virella-Lowell I, Zusman B, Foust K, Loiler S, Conlon T, Song S, Chesnut KA, Ferkol T, Flotte TR. Enhancing RAAV vector expression in the lung. J Gene Med 2005;7:842–850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sirninger J, Muller C, Braag S, Tang Q, Yue H, Detrisac C, Ferkol T, Guggino WB, Flotte TR. Functional characterization of a recombinant adeno-associated virus 5-pseudotyped cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator vector. Hum Gene Ther 2004;15:832–841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cruz PE, Mueller C, Cossette TL, Golant A, Tang Q, Beattie SG, Brantly M, Campbell-Thompson M, Blomenkamp KS, Teckman JH, et al. In vivo post-transcriptional gene silencing of alpha-1 antitrypsin by adeno-associated virus vectors expressing siRNA. Lab Invest 2007;87:893–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Singh AP, Chauhan SC, Andrianifahanana M, Moniaux N, Meza JL, Copin MC, van Seuningen I, Hollingsworth MA, Aubert JP, Batra SK. Muc4 expression is regulated by cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator in pancreatic adenocarcinoma cells via transcriptional and post-translational mechanisms. Oncogene 2007;26:30–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bloemberg GV, O'Toole GA, Lugtenberg BJ, Kolter R. Green fluorescent protein as a marker for Pseudomonas spp. Appl Environ Microbiol 1997;63:4543–4551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hoffmann N, Rasmussen TB, Jensen PO, Stub C, Hentzer M, Molin S, Ciofu O, Givskov M, Johansen HK, Hoiby N. Novel mouse model of chronic Pseudomonas aeruginosa lung infection mimicking cystic fibrosis. Infect Immun 2005;73:2504–2514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhou L, Dey CR, Wert SE, DuVall MD, Frizzell RA, Whitsett JA. Correction of lethal intestinal defect in a mouse model of cystic fibrosis by human CFTR. Science 1994;266:1705–1708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mueller C, Torrez D, Braag S, Martino A, Clarke T, Campbell-Thompson M, Flotte TR. Partial correction of the CFTR-dependent ABPA mouse model with recombinant adeno-associated virus gene transfer of truncated CFTR gene. J Gene Med 2008;10:51–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rodriguez-Pineiro AM, Ayude D, Rodriguez-Berrocal FJ, Paez de la Cadena M. Concanavalin A chromatography coupled to two-dimensional gel electrophoresis improves protein expression studies of the serum proteome. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci 2004;803:337–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hughes RC, Mills G. Analysis by lectin affinity chromatography of N-linked glycans of BHK cells and ricin-resistant mutants. Biochem J 1983;211:575–587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pilobello KT, Slawek DE, Mahal LK. A ratiometric lectin microarray approach to analysis of the dynamic mammalian glycome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2007;104:11534–11539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Varki A. Essentials of glycobiology. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2009. [PubMed]

- 43.Moore JS, Kulhavy R, Tomana M, Moldoveanu Z, Suzuki H, Brown R, Hall S, Kilian M, Poulsen K, Mestecky J, et al. Reactivities of N-acetylgalactosamine-specific lectins with human IgA1 proteins. Mol Immunol 2007;44:2598–2604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hoyle BD, Williams LJ, Costerton JW. Production of mucoid exopolysaccharide during development of Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. Infect Immun 1993;61:777–780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schroeder TH, Zaidi T, Pier GB. Lack of adherence of clinical isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa to asialo-GM(1) on epithelial cells. Infect Immun 2001;69:719–729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hutchison ML, Govan JR. Pathogenicity of microbes associated with cystic fibrosis. Microbes Infect 1999;1:1005–1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schroeder TH, Reiniger N, Meluleni G, Grout M, Coleman FT, Pier GB. Transgenic cystic fibrosis mice exhibit reduced early clearance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa from the respiratory tract. J Immunol 2001;166:7410–7418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ferlinz K, Hurwitz R, Moczall H, Lansmann S, Schuchman EH, Sandhoff K. Functional characterization of the N-glycosylation sites of human acid sphingomyelinase by site-directed mutagenesis. Eur J Biochem 1997;243:511–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Su Y, Royle L, Radcliffe CM, Harvey DJ, Dwek RA, Martinez-Pomares L, Rudd PM. Detailed N-glycan analysis of mannose receptor purified from murine spleen indicates tissue specific sialylation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2009;384:436–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.