Abstract

© 2009 iStockphoto.com/ChrisSchmidt

© 2009 iStockphoto.com/ChrisSchmidt

This article focuses on a review of the literature related to the known prevalence of psychotic events in individuals with Alzheimer’s disease and associated aggressive, violent behavior toward family caregivers. It also describes the impact of behavioral disturbances on family caregivers and how use of the Progressively Lowered Stress Threshold model and nonpharmacological interventions cited in the literature can help manage these behaviors. Geriatric nurses armed with this information will be better prepared to provide caregivers with much-needed education to better understand psychotic events, as well as strategies to cope with associated behaviors.

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a common chronic condition of older adults, causing progressive irreversible deterioration to the cerebral cortex. Affecting more than 5 million Americans (Chico, 2005), AD slowly robs individuals of their ability to remember, communicate, make judgments, function in instrumental and basic activities of daily living, tolerate stress, and interact socially. The Alzheimer’s Association (2007) projects that between 11 and 16 million Americans older than age 65 will have AD by the year 2050, and of those affected, 60% will be older than age 85. It is estimated that the current direct and indirect costs of AD and other dementias is more than $148 billion annually (Alzheimer’s Association, 2007).

ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE

Along with the devastating cognitive changes that occur, many individuals with AD experience behavioral complications such as depression, wandering, relentless pacing, agitation, aggression, alterations in sleep patterns, and disturbances in thought processes (Smith & Buckwalter, 2005). These changes in thought processes often manifest as psychotic events. Psychotic events are characterized as a distortion of reality displayed as paranoid delusions, hallucinations, and/or misidentification syndromes (a type of delusion). Hallucinations are perceptual distortions that are not explained by the person’s cultural or religious beliefs and may involve auditory, visual, tactile, gustatory, or olfactory senses. Delusions are false fixed beliefs that often involve a misperception of an experience and are unaffected by rational argument (Boyd, 2008). Estimates of the incidence of delusions in AD vary because they have been diagnosed differently between studies (Bassiony & Lyketsos, 2003) but range from 10% to 73% (Chico, 2005; Fischer, Bozanovic-Sosic, & Norris, 2004); the incidence of hallucinations ranges from 4% to 76% (Bassiony & Lyketsos, 2003; Chico, 2005), and the incidence of misidentification syndrome is estimated to range from 5% to 30% (Chico, 2005).

Individuals with AD experiencing paranoid delusions may believe a family caregiver is trying to physically harm them, steal from them, or engage in an adulterous relationship with a best friend. The person experiencing auditory hallucinations may believe he or she hears voices in the house and demand that the caregiver find those responsible and remove them from the home. Those experiencing misidentification syndrome may no longer recognize their spouse and insist the stranger providing care leave the home.

The burden of caring for individuals with AD usually falls on their family members, who may be caregivers for many years. Family caregivers of those with AD experience a great deal of stress throughout the long and changeable disease process (Hall, 1999). Along with the cognitive changes that occur, family caregivers face many behavioral challenges with their loved one as the disease progresses. In particular, psychotic events represent a severe stressor for the person with dementia and the caregiver (Chico, 2005; Fischer et al., 2004; Jeste, Meeks, Kim, & Zubenko, 2006; Smith & Buckwalter, 2005) that leads to earlier institutionalization (Chico, 2005; Fischer et al., 2004; Jeste et al., 2006).

PROGRESSIVELY LOWERED STRESS THRESHOLD MODEL

In an effort to provide caregivers with a tool to manage behaviors in those with AD, Hall developed the Progressively Lowered Stress Threshold (PLST) model (Hall & Buckwalter, 1987), which has been used extensively for planning individualized care for those with dementia. This model teaches caregivers effective interventions for coping with behaviors. The PLST model was evaluated by the National Caregivers Training Project, a multisite national study funded by the National Institute of Nursing Research, and has been used as a conceptual model for a number of other institutional, community-based, and dissertation studies (Smith, Gerdner, Hall, & Buckwalter, 2004).

A number of the caregivers participating in the National Institute of Nursing Research study reported that their family members with AD experienced psychotic events, including paranoid delusions, hallucinations, and misidentification syndrome. Caregivers also reported severe behavioral disturbances associated with the care recipient’s experience of psychotic events (Hall, 1999). Care recipients in the experimental group (whose caregivers received the PLST training intervention) had a 2.9% incidence of psychosis compared with 28.3% in the control group. Hall (1999) proposed that the higher incidence of reported psychotic symptoms in the control group may have occurred because these symptoms are stress related and, in the experimental group, stress was mediated by the PLST intervention. Caregivers who received the PLST intervention identified fewer episodes of psychosis in their care recipients (Hall, 1999).

Due to the frequency of reports of psychotic events in individuals with dementia and the severity of the associated behavioral disturbances, it is imperative that nurses caring for older adults with dementia are knowledgeable and well prepared to provide caregivers with much-needed education, support, and appropriate referral. This article focuses on a review of the literature related to the known prevalence of psychotic events in individuals with AD and associated aggressive, violent behavior toward family caregivers. It also describes the impact of behavioral disturbances on family caregivers and how use of the PLST model, as well as nonpharmacological interventions cited in the literature, can help manage these behaviors. Geriatric nurses armed with this information will be better prepared to help caregivers understand the psychotic events and offer strategies to cope with the associated behaviors.

PSYCHOTIC EVENTS

In 1907, Dr. Alois Alzheimer, in his original publication, described a patient who showed both intellectual and psychiatric symptoms (Alzheimer, 1907/1987). Besides memory loss, disorientation, and apraxia, the patient exhibited depression and paranoid delusions manifested as delusional jealousy. However, since that time, investigations have focused primarily on the cognitive and neurobiological aspects of dementia, with comparatively little interest in the characteristics and mechanisms of noncognitive symptoms of the disease.

Estimates of the prevalence of psychotic events in individuals with AD have largely been obtained from cross-sectional studies of clinically diagnosed patients evaluated in diverse clinical settings. As stated previously, the estimates of delusions in AD have ranged from 10% to 73% (Chico, 2005). It appears that this wide range is the result of varying definitions of psychotic events. Because of this, obtaining an accurate estimate of the prevalence of psychotic events and related behavioral problems is problematic.

Delusions and hallucinations do occur in all stages of AD, with at least half of AD patients (with no prior psychiatric history) displaying psychosis at some point in the illness (Bassiony & Lyketsos, 2003). The presence of delusions and hallucinations fluctuates throughout the course of the disease, increasing slowly as the illness progresses (Chico, 2005; Fischer et al., 2004).

Delusions

The most frequently reported psychotic symptoms in AD are persecutory delusions, most frequently the delusion of theft (Bassiony & Lyketsos, 2003; Ropacki & Jeste, 2005). Five subtypes of delusions have been identified in AD and include paranoid, hypochondriacal, Capgras syndrome (misidentification of a spouse or family member), house misidentification, and grandiosity (Buckwalter, 1993). Misidentification is a false belief that is temporary and neither firmly fixed nor held by the person. Misidentifications involve the belief that the identity of a person, object, or place have been changed or altered. The person with AD fails to recognize family members or even themselves (Chico, 2005). Other delusional subtypes include phantom boarders, spousal infidelity, and fear of the caregiver plotting to leave (Fischer et al., 2004).

In AD, delusions are associated with accelerated cognitive decline, increased aggressive behavior toward the caregiver, higher levels of caregiver stress, and earlier institutionalization (Fischer, Bozanovic, Atkins, & Rourke, 2006; Fischer et al., 2004). Delusional patients with AD have been found to be more aggressive, severe wanderers, and engage in more purposeless and/or inappropriate activities (Bassiony & Lyketsos, 2003). Delusions in AD have also been associated with greater functional impairment, worse general health, and severe depression (Bassiony & Lyketsos, 2003).

Hallucinations

In AD, the most commonly reported hallucinations are visual and auditory, but somatic, olfactory (smell), and tactile hallucinations also occur. Individuals with AD who are hallucinating are often more prone to verbal outbursts, aggressive behavior, functional impairment, asocial behavior, and falls (Bassiony & Lyketsos, 2003).

Agitation

Estimates of the prevalence of agitation in people with AD range from 20% to 82% (Gerdner, Buckwalter, & Hall, 2005; Jeste et al., 2006). Agitation is often associated with psychosis but may also be a response to medical illness, pain, or psychosocial factors (Cohen-Mansfield, 2005; Jeste et al., 2006). Three subtypes of agitated behaviors have been identified: aggressive (e.g., hitting, kicking, pushing, scratching, tearing things, biting, spitting, cursing, verbal aggression), physically nonaggressive (e.g., pacing, inappropriate dressing and undressing, trying to get to a different place, handling things inappropriately, general restlessness, repetitious mannerisms), and verbal/vocal/agitated behaviors (e.g., complaining, constant requests for attention, negativism, repetitious sentences or questions, screaming) (Cohen-Mansfield, 2005).

Aggressive behavior occurs more frequently in men, those with greater cognitive impairment, and those with a prior history of aggression and conflict with the caregiver (Jeste et al., 2006; O’Leary, Jyringi, & Sedler, 2005). One study found that approximately 25% of patients with dementia were physically aggressive toward their caregivers and that physical aggression toward a partner was more likely if the patient had a history of conduct disorder (O’Leary et al., 2005).

IMPACT ON FAMILY CAREGIVERS

It is estimated that 70% of individuals with AD and other dementias live at home and are cared for by family and friends (Alzheimer’s Association, 2007). Family caregivers may cope with the cognitive changes and physical limitations experienced by the person with dementia, but the appearance of delusions, hallucinations, and misidentification syndrome, with resultant behaviors, may finally compel them to seek nursing home placement. Caregivers of patients experiencing psychotic events may equate these behaviors with “craziness” or insanity. They may see psychotic events as less socially acceptable than other behaviors resulting from cognitive changes, such as forgetfulness, which are inherent in the disease process. Psychotic behaviors are often more difficult to understand and control, yet are persistent and frequently directed toward the primary caregiver, who becomes a convenient target. Caregiver abuse is one of main reasons for institutionalization of individuals with AD (O’Leary et al., 2005).

These added challenges occur during what may be an already stressful experience for the caregiver as he or she provides care for the person with dementia and copes with the grief and gradual loss of the person once known to them. Consequently, caregivers may experience even greater stress as a result of their attempts to understand and manage these behaviors. Management of behavior resulting from the experience of psychotic events may become more than family caregivers can handle, particularly if they perceive these behaviors as embarrassing and socially unacceptable.

APPLICATION OF THE PLST MODEL

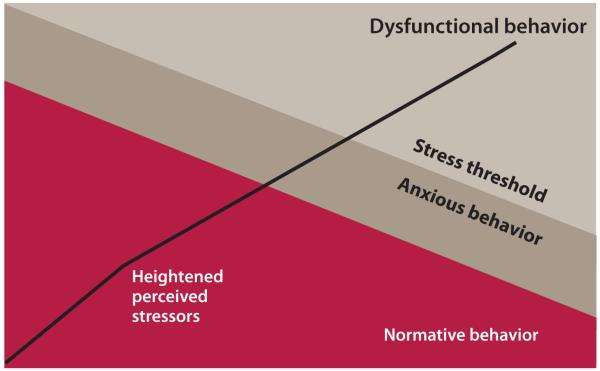

The PLST model (Figure) was initially developed to help family caregivers organize observations and make care decisions. It has been used to plan and evaluate care in every setting where individuals with AD are found. The model was derived using psychological theories of stress, adaptation, and coping, in addition to behavioral and physiological research on AD. The PLST model divides symptoms of dementing illness into four clusters (Hall, 1999):

Cognitive or intellectual losses.

Affective or personality changes.

Conative or planning losses that cause a predictable decline in ability to perform functional activities.

Decrease in the stress threshold, causing dysfunctional behavior such as agitation or catastrophic reactions—meaning a sudden change in baseline behavior characterized by cognitive and social inaccessibility.

Figure.

Progressively Lowered Stress Threshold (PLST) model.

Source. Hall, G.R., & Buckwalter, K.C. (1987). Progressively lowered stress threshold: A conceptual model for care of adults with Alzheimer’s disease. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 1, 399-406. Copyright Elsevier. Reprinted with permission.

The PLST model hypothesizes that symptoms in the fourth cluster (decrease in stress threshold) are related to the progressive loss of the ability to cope. When stress exceeds the individual’s neurological ability to cope, he or she becomes increasingly anxious until the stress threshold is exceeded. This results in an episode of one or more behaviors in the fourth cluster, such as agitation, catastrophic reactions, or social inaccessibility (inability to communicate) (Hall, 1999). These reactions may occur during, immediately after, or up to a day after a particular causative event. Like all AD symptoms, dysfunctional behaviors are rare and mild in the early course of the disease but increase in prevalence and intensity with disease progression (Hall, 1999).

The PLST model identifies six common stressors that may produce dysfunctional episodes and sudden functional decline:

Fatigue.

Change of environment, routine, or caregiver.

Misleading stimuli or inappropriate stimulus levels.

Internal or external demands to achieve that exceed functional capacity.

Physical stressors, such as pain, discomfort, infection, acute illness, and depression.

Affective response to loss.

Nurses can use their knowledge of the stressor groups to guide care planning and as a quick assessment measure for causative factors after a dysfunctional episode or sudden functional loss has occurred. Planning care involves teaching caregivers about symptom presentation, recognition of dysfunctional behaviors, compensatory techniques to minimize presence of the six stressors, and use of the individual’s preferred routine to maintain as safe and satisfying a lifestyle as possible and avoid catastrophic reactions.

In-home caregivers are taught how to adapt to their loved one’s changing needs with the least amount of disruption to family members (Hall, 1999). It is important to note that although psychotic manifestations cannot be eliminated by the PLST interventions, their negative effect on the caregiver and care recipient may be decreased (Hall, 1999). For example, nurses could work with caregivers to identify that misleading stimuli (third in the common stressors list above), such as watching a television show or movie in which someone is raped or murdered, could be incorporated into the person’s delusional system. Nurses could point out to the caregiver that this kind of stimuli can lead to agitation and fearfulness in those with dementia, who may become convinced that someone is actually trying to harm them or a friend or family member. Nurses can then recommend other activities or less violent shows or movies that the caregiver might substitute and monitor if the delusions of harm diminish and the person becomes more calm and less frightened.

The PLST model suggests six principles of care that guide interventions that help caregivers manage stress levels of the person with AD. The six principles of care and associated interventions are outlined in Table 1. Interventions should be individualized based on the person’s distinct abilities and needs.

TABLE 1. PROGRESSIVELY LOWERED STRESS THRESHOLD MODEL: SIX PRINCIPLES OF CARE.

| Six Principles of Care | Interventions |

|---|---|

|

1. Maximize safe function by sup-

porting losses. |

|

|

2. Provide unconditional positive

regard. |

|

|

3. Use anxiety and avoidance to

gauge activity and stimulation levels. |

|

|

4. Teach caregivers to observe and

listen to patients. |

|

|

5. Modify environments to support

losses and enhance safety. |

|

|

6. Provide ongoing education, sup-

port, care, and problem solving. |

|

INDIVIDUAL EXAMPLE

Mary (pseudonym), age 87, moved into an assisted living facility 3 months ago. Her daughter contacted the facility’s nursing staff to discuss concerns about her mother’s change in behavior during the past few weeks. Each time she visits her mother, her mother reports that her belongings have been stolen “again” by one of the “no good” housekeeping staff. At first, Mary’s daughter was concerned this might be true, but she has closely monitored her mother’s possessions and found no evidence of theft. She told the nurse she is frustrated because she has tried everything she can think of to convince her mother that no one is taking her belongings. To her dismay, each time she comes to visit, her mother immediately tells her “it has happened again” and that “more belongings have been taken by those sneak-thief intruders.” Mary perseverates on this delusion and cannot be convinced it is not true.

During the past few visits, Mary has become increasingly agitated, as evidenced by speaking in a loud voice, pacing around her room, repeatedly looking through her closet and dresser drawers trying to find her missing belongings, hoarding objects such as food, and becoming verbally aggressive as she accuses staff of stealing her things. Using the PLST model, the nurse works collaboratively with Mary’s daughter and the staff to develop the care plan outlined in Table 2. Readers are also referred to a detailed individual example (Smith, Hall, Gerdner, & Buckwalter, 2006) that applied the PLST model across the continuum of care from independent living to assisted living to brief hospitalization to a skilled care facility.

TABLE 2. PROGRESSIVELY LOWERED STRESS THRESHOLD (PLST) MODEL CARE PLAN FOR MARY.

| PLST Principle | Identifed Problem/Need | Interventions |

|---|---|---|

|

1. Maximize safe

function by support- ing losses. |

Unfamiliar environment, staff, residents, and routine. |

|

|

2. Provide uncon-

ditional positive regard. |

Staff and family knowledge deficits regarding psychotic events (e.g., delusion). |

|

|

3. Use anxiety and

avoidance to gauge activity and stimula- tion levels. |

Stress reaction to losses (real and perceived). |

|

|

4. Teach caregivers to

observe and listen to patients. |

Perseveration regarding be- lief that personal items have been stolen. |

|

|

5. Modify environ-

ments to support losses and enhance safety. |

Belief that belongings are being stolen. |

|

|

6. Provide ongoing

education, support, care, and problem solving. |

Knowledge deficit among staff and family about delu- sions and PLST model. |

|

NONPHARMACOLOGICAL INTERVENTIONS

Several authors have suggested nonpharmacological strategies for individuals with AD experiencing psychosis to minimize agitation and disruptive behavior. The strategies identified by Smith and Buckwalter (2005) focus on sensory enhancement (e.g., music, aromatherapy, Snoezelen® therapy), socialization (e.g., reminiscence, video respite, simulated presence therapy), and structured activities. Cohen-Mansfield (2005) suggested providing social support and contact (e.g., talking with the person, videos or audiotapes of family members, music therapy, pet therapy, dolls, massage), engaging activities (e.g., stimulation, active engagement, allowing self-stimulation), and relief from discomfort (e.g., pain, hearing or vision problems, positioning, activities of daily living). Studies that have examined the effectiveness in these interventions have provided mixed results due to methodological issues similar to those in studies of pharmacological interventions. However, providing an individualized approach based on the person’s needs, abilities, and preferences can be effective (Smith & Buckwalter, 2005).

CONCLUSION AND CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS

The treatment and management of noncognitive, behavioral disturbances is a growing area of interest and research in the management of AD. The cause(s) of AD are becoming better understood through research on genetic, neurochemical, and neuroanatomic mechanisms of the disease. However, the multiple noncognitive manifestations of AD, including behavioral disturbances, continue to be devastating to people with AD and their caregivers.

A large percentage of those with AD experience psychotic events leading to behavioral problems and increased stress in the caregiving process. Caregivers who may otherwise feel competent to care for their family member’s physical and cognitive losses may feel inadequate if the person is experiencing psychotic events. It also may be that society in general stigmatizes individuals experiencing psychotic symptoms, and thus caregivers may feel ashamed or afraid of these behaviors. Caregivers may be willing to accept their loved one’s cognitive and physical losses but not what they perceive as “crazy” or aggressive behavior.

The PLST model provides a framework for caregivers to better understand and manage behaviors. Using this model, caregivers can learn about the common stressors that may produce dysfunctional episodes and sudden functional decline. As a result, caregivers can better recognize symptoms and implement compensatory techniques to minimize adverse responses. Geriatric nurses who provide caregivers with education about symptoms and how to better manage challenging behaviors may decrease caregivers’ stress level and allow them to maintain their loved one at home for a longer period of time.

KEYPOINTS.

Psychotic Events in Alzheimer’s Disease

Lindsey, P.L., & Buckwalter, K.C. (2009). Psychotic Events in Alzheimer’s Disease: Application of the PLST Model. Journal of Gerontological Nursing, 35(8), 20-27.

Caregivers of individuals with Alzheimer’s disease may find they are able to cope with the cognitive changes and physical limitations experienced by their loved one, but the appearance of psychotic events and resultant behavior may feel overwhelming and may lead to early institutionalization of the care recipient.

The Progressively Lowered Stress Threshold (PLST) model provides a framework for caregivers to better understand and manage behavior, thus reducing the negative effect of psychotic events on the caregiver and the care recipient.

By providing caregiver education about the PLST model and suggesting other nonpharmacological interventions to manage behavior, geriatric nurses may help reduce caregiver stress and prevent early institutionalization of care recipients.

Footnotes

The authors disclose that they have no significant financial interests in any product or class of products discussed directly or indirectly in this activity. Data used in this article were from grant R01 NR03234, “PLST Model: Effectiveness for Rural ADRD Caregivers,” National Institute of Nursing Research, 1992-1997 (K.C. Buckwalter, PI). The authors thank Dr. Linda Gerdner for sharing her model slides.

Contributor Information

Pamela L. Lindsey, Illinois State University Mennonite College of Nursing, Normal, Illinois, and a 2007-2009 John A. Hartford Foundation and Atlantic Philanthropies Claire M. Fagin Fellow.

Kathleen C. Buckwalter, John A. Hartford Center of Geriatric Nursing Excellence, The University of Iowa College of Nursing, Iowa City, Iowa.

REFERENCES

- Alzheimer A. About a peculiar disease of the cerebral cortex. In: Jarvik L, Greenson H, editors. Alzheimer Disease and Associated Disorders. 1. Vol. 1. 1987. pp. 7–8. Original work published 1907. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alzheimer’s Association Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures 2007. 2007 Retrieved October 1, 2008, from http://www.alz.org/national/documents/Report_2007FactsAndFigures.pdf.

- Bassiony MM, Lyketsos CG. Delusions and hallucinations in Alzheimer’s disease: Review of the brain decade. Psychosomatics. 2003;44:388–401. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.44.5.388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd MA. Psychiatric nursing: Contemporary practice. 4th ed. Lippincott Williams &Wilkins; Philadelphia: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Buckwalter KC. Are you really my nurse, or are you a snake sheriff? Journal of Gerontological Nursing. 1993;19(6):45–46. doi: 10.3928/0098-9134-19930601-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chico GF. Targeting behavior problems in Alzheimer’s disease. Emergency Medicine. 2005;37(7):9–12. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen-Mansfield J. Nonpharmacological interventions for persons with dementia. Alzheimer’s Care Quarterly. 2005;6:129–145. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer C, Bozanovic R, Atkins JH, Rourke SB. Treatment of delusions in Alzheimer’s disease—Response to pharmacotherapy. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders. 2006;22:260–266. doi: 10.1159/000094975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer C, Bozanovic-Sosic R, Norris M. Review of delusions in dementia. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Dementias. 2004;19:19–23. doi: 10.1177/153331750401900104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerdner LA, Buckwalter KC, Hall GR. Temporal patterning of agitation and stressors associated with agitation: Case profiles to illustrate the progressively lowered stress threshold model. Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association. 2005;11:215–222. [Google Scholar]

- Hall GR. Testing the PLST model with community-based caregivers. Dissertation Abstracts International. 1999;60:577–B. Doctoral dissertation, The University of Iowa, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Hall GR, Buckwalter KC. Progressively lowered stress threshold: A conceptual model for care of adults with Alzheimer’s disease. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing. 1987;1:399–406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeste DV, Meeks TW, Kim DS, Zubenko GS. Research agenda for DSM-V: Diagnostic categories and criteria for neuropsychiatric syndromes in dementia. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry and Neurology. 2006;19:160–171. doi: 10.1177/0891988706291087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary D, Jyringi D, Sedler M. Childhood conduct problems, stages of Alzheimer’s disease, and physical aggression against caregivers. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2005;20:401–405. doi: 10.1002/gps.1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ropacki SA, Jeste DV. Epidemiology of and risk factors for psychosis of Alzheimer’s disease: A review of 55 studies published from 1990 to 2003. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;162:2022–2030. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.11.2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith M, Buckwalter K. Behaviors associated with dementia. American Journal of Nursing. 2005;105(7):40–52. doi: 10.1097/00000446-200507000-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith M, Gerdner LA, Hall GR, Buckwalter KC. History, development, and future of the progressively lowered stress threshold: A conceptual model for dementia care. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2004;52:1755–1760. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52473.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith M, Hall GR, Gerdner L, Buckwalter KC. Application of the progressively lowered stress threshold model across the continuum of care. Nursing Clinics of North America. 2006;41:57–81. doi: 10.1016/j.cnur.2005.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]