Abstract

Background & objectives:

Tuberculosis (TB) infection control interventions are not routinely implemented in many Sub-Saharan African countries including Nigeria. This study was carried out to ascertain the magnitude of occupationally-acquired pulmonary TB (PTB) among health care workers (HCWs) at two designated DOTS centers in Ibadan, Nigeria.

Methods:

One year descriptive study (January-December 2008) was carried out at the University College Hospital and Jericho Chest Hospital, both located in Ibadan, Nigeria. A pre-tested questionnaire was used to obtain socio-demographic data and other relevant information from the subjects. Three sputum samples were collected from each subject. This was processed using Zeihl-Neelsen (Z-N) stains. One of the sputum was cultured on modified Ogawa egg medium incubated at 37°C for six weeks. Mycobacterium tuberculosis was confirmed by repeat Z-N staining and biochemical tests.

Results:

A total of 271 subjects, 117 (43.2%) males and 154 (56.8%) females were studied. Nine (3.3%) had their sputum positive for acid fast bacilli (AFB) while six (2.2%) were positive for culture. The culture contamination rate was 1.8 per cent. Significantly, all the six culture positive samples were from males while none was obtained from their female counterparts. About half of the AFB positive samples were from subjects who have spent five years in their working units. Eight AFB positive cases were from 21-50 yr age group while students accounted for seven AFB positive cases.

Interpretation & conclusions:

The study shows that occupationally-acquired PTB is real in Ibadan. Further studies are needed to ascertain and address the magnitude of the problem.

Keywords: Health care workers, infection control, Nigeria, TB

The risk of transmitting Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the causative agent of tuberculosis (TB) from infected patients to health care workers (HCWs) has been recognized for many years1. The risk depends on the settings, occupation, patient population and effectiveness of the TB control measures2. The World Health Organization (WHO) has proposed practical and low cost interventions to reduce nosocomial transmissions of TB in resourced constrained settings3. These recommendations emphasize prompt diagnosis and rapid treatment of cases rather than use of expensive technologies like isolation rooms and respirators3. However, despite the widespread implementation of the Directly Observed Therapy Short Course (DOTS) strategy, which is internationally recommended, compliance with these simple guidelines is generally poor in low-income countries which harbour high burden of the disease4.

In Nigeria and in other high burden countries, the primary focus of the National TB Control Programmes (NTCP) is scaling-up of DOTS services while nosocomial transmission of the disease is relegated to the background5. As a result, TB infection control interventions are not routinely implemented, in contrast to what happens in high income countries with low prevalence of TB where infection control policy is routinely observed5.

Despite the high prevalence of TB in Nigeria with its antecedent high morbidity and mortality, little is known about occupationally-acquired TB in the country. This study was, therefore, carried out to determine the magnitude of occupationally-acquired TB among health care workers (HCWs) at two DOTS centers in Ibadan, Nigeria.

Material & Methods

Study design & area: This is a descriptive epidemiological study in which HCWs such as doctors, nurses, radiographers, laboratory scientists, laboratory assistants, ward maids and students who were involved in the management of TB patients were screened for pulmonary TB (PTB).

The study was carried out at the two designated DOTS centers, the University College Hospital (UCH), Ibadan, a tertiary health care facility and Jericho Chest Hospital (JCH) which serves as a referral secondary health care center.

The two health institutions are located within Ibadan metropolis. Ibadan is the capital city of Oyo State of Nigeria with a population of about five million6. The TB laboratory of the Department of Medical Microbiology and Parasitology is located at the UCH. The laboratory is a designated facility for isolation of M. tuberculosis in the Southwestern part of the country. It is supported by Damien Foundation, Belgium through the NTCP of the Federal Ministry of Health, Abuja.

Study population: Of the 385 HCWs working in 2 centre, (UCH and JCH DOTS), 271 (70.4%) subjects gave their consent and participated in the study from January to December 2008. The study protocol was approved by the University of Ibadan and UCH joint ethical committee. Verbal and written informed consent was obtained from the subjects before enrollment into the study. Those who refused to give written consent were excluded.

A pre-tested questionnaire was used by a trained counselor to obtain information on demographic characteristics, social and medical history from the subjects. Other important information about PTB such as previous BCG vaccination, contact with an index case and exposure to tuberculin skin test were also obtained.

Laboratory investigations: Three early morning sputum were collected from each consenting asymptomatic subject. The samples were transported to TB laboratory of the department of Medical Microbiology and Parasitology, UCH, for immediate processing. Each sample was smeared, air-dried, fixed and stained with Z-N reagents. The staining procedure was controlled by using known AFB slide and slide stained with egg albumin as positive and negative controls respectively.

The results was read according to the grading system of the International Union Against TB and Lung Diseases as - , +, ++, +++7. Thereafter, the sputum was decontaminated using 4 per cent NaOH. The resulting solution was mixed using vortex mixer. About one ml from the mixture was inoculated onto prepared modified Ogawa egg medium as previously demonstrated8 and incubated at 37°C for six weeks. M. tuberculosis strain H37Rv and sterile Ogawa medium were used as positive and negative controls respectively. Contamination on Ogawa medium was determined by looking for growth before two weeks of incubation and by carrying out Z-N reaction and standard biochemical tests9. Subjects from whom AFB positive samples were obtained and or those with culture positive samples were referred to the chest physician for further re-evaluation.

Molecular studies and drug susceptibility testing of the isolates were not done due to inadequate facilities.

Statistical analysis: All data were coded and analyzed using statistical software SPSS version 10.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA). Frequency tables were used to describe demographic characteristics and laboratory variables while Chi square test was used to measure the association between categorical variables where necessary.

Results

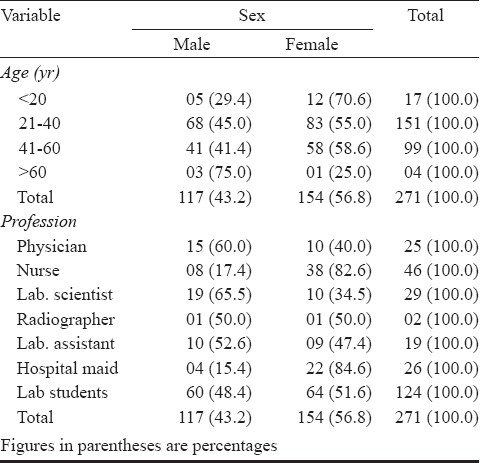

Consent was sought from 385 HCWs who were working at the two centers, of whom 271 subjects (70.4%) gave consent and participated in the study giving a male: female ratio of 0.75 to 1.00 respectively. Only four (1.5%) were over 60 yr while the majority, 151 (55.7%) were aged 21-40 yr. Of the 271 subjects, 102 (37.6%) were professionals while non-professionals accounted for 169 (62.4%) (Table I).

Table I.

Demographic characteristics of the subjects by sex

The majority, 160 (59.0%) of the subjects had been working in their units for more than two years while 64 (23.6%) had not spent up to one year in their various units. Most 254 (93.7%) reported negative history of chronic cough while a higher percentage 257 (94.8%) denied any history of smoking. In relation to alcohol consumption, 44 (16.2%) gave history of alcohol intake, the majority 208 (76.8%) gave a negative history while 19 (7.0%) did not give any definite answer.

Eleven (4.1%) subjects agreed to recently have contact with patients with chronic cough, 178 (65.7%) gave negative response while 82 (30.3%) did not answer the question.

Concerning previous history of tuberculin skin test (bubble under the skin), 36.9 per cent of the subjects had a positive tuberculin skin test in the past while 63.1 per cent of them had a negative result. The majority of the subjects 164 (60.5%) did not receive Bacille-Calmette Guerin (BCG) vaccination, only 88 (32.8%) had received BCG vaccination while 19 (6.6%) did not remember. In terms of previous treatment for TB infection, 222 (81.9%) gave negative answer, while 49 (18.1%) agreed to have had previous treatment for TB before they started working in the hospital.

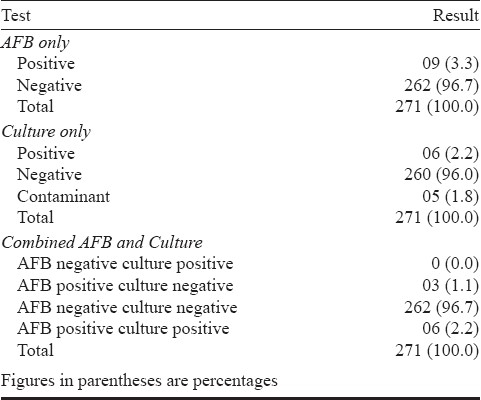

Nine (3.3%) of the 271 subjects had their sputum positive for AFB on microscopy while 262 (96.7%) were negative. Six (2.2%) samples were positive for culture, 260 (95.9%) were negative while five (1.8%) were contaminants. The majority, 262 (96.7%) were both AFB and culture negative while only six (2.2%) were both AFB and culture positive (Table II). Eight of the nine AFB positive samples were obtained from subjects aged 21-50 yr while only one was from adolescent age group. The association between AFB positivity and age of the subjects was not statistically significant.

Table II.

AFB and Culture results of the HCWs at the two DOTS centers

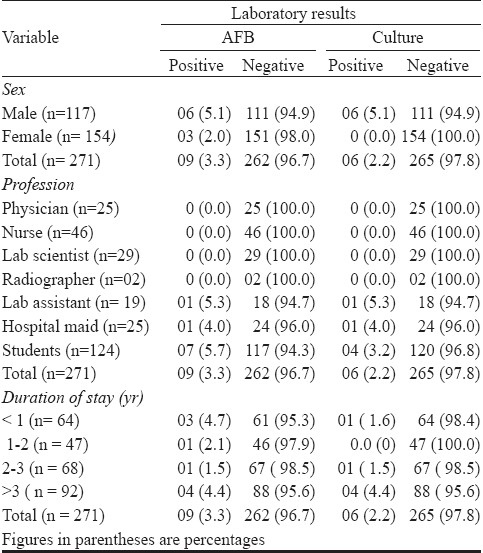

In terms of distribution of AFB positive samples by sex of the subjects, six (5.1%) were obtained from males (n=117) while females accounted for three (2.0%) cases. All the six AFB positive samples were positive for culture. All the six culture positive samples were from males while none was obtained from their female counterparts (Table III). More than three quarters (77.7%) of the positive AFB samples were from students while none was obtained from the professionals (physicians, nurses, laboratory scientists and radiographers).

Table III.

Laboratory results by sex, profession and duration of stay Laboratory results

Four of the nine AFB positive samples were from subjects who had been working in their units for the past five years, three spent less than one year at their duty post while those with 1-2 and 2-3 yr experience, each had one AFB sample positivity.

Discussion

The risk of transmission of M. tuberculosis from PTB patients to HCWs is a neglected problem in low-income countries with high burden of TB10. The infection rates of 3.3 per cent by microscopy and 2.2 per cent by culture obtained from this study is similar to 2.1 and 3.1 per cent obtained in Malawian and South African studies respectively11,12 but higher than 1.5 per cent reported by Salami and Oluboyo in their retrospective review of 2,173 cases in Ilorin in 200813. This may be due to the fact that previous study did not include secondary and primary health care centers where infection control policy might likely be compromised. The diagnostic yield of microscopy (3.3%) was higher than the 2.2 per cent obtained for culture. This may be as a result of high rate of false positivity which is often associated with microscopy as it does not distinguish pathogenic mycobacteria from the commensals. Furthermore, smear false positivity is often associated with poor quality of sputum samples, deficiencies in preparation of stains, staining procedure or examination of stained slides14. The fact that all the six culture positive isolates were also AFB positive while the remaining three AFB positive samples were negative on culture indicates that performance of smear microscopy as a diagnostic tool in this study was reliable.

The mycobacterial culture contamination rate of 1.8 per cent obtained in this study was lower than that of 5.1 per cent obtained in the same center years back15. This may be attributed to the fact that previous study was carried out in children. Previous report has shown that collection and processing of specimen for TB diagnosis in children is often problematic and prone to contamination especially in endemic settings with limited human and infrastructural facilities16. Also, recent trainings in Good Laboratory Practice by the laboratory scientists may account for their subsequent improvement in processing clinical specimens.

Almost all (eight of the nine) positive AFB samples were from the age bracket 20-60 yr. This is worrisome as this age group constitutes the economic vibrant group of the population. TB infection affecting the vibrant work force may further aggravate shortage of HCWs which may cripple delivery of health care systems in the country.

Majority of the infected samples were from subjects who had spent more than two years in their units. Longer exposure of the HCW to an infectious PTB patient increases the risk of contacting occupationally-acquired TB10,17.

Small samples and study area covering only 2 DOTS centers are some of the study limitations. Other limitations include exclusion of testing for latent TB infection (LTBI). This was as a result of shortcomings associated with use of the only available diagnostic tool- Tuberculin (Mantoux) skin test (TST). These include invasive nature of the test, the need for the patient to come back for follow up TST reading, cross-reactivity with environmental mycobacteria and previous BCG vaccination. There is a need to assess the magnitude of LTBI among HCWs using more reliable serological assays such as the T-cell based assays which measure the interferon –gamma released after stimulation by M. tuberculosis. Examples of such assays include QuatiFeron TB Gold by Cellestis InC, USA and T- SPOT™. TB by Oxford Immunotech, England18. Chest radiograph and HIV serological status of the subjects were also not done. This was primarily due to financial constraints. Assessment of chest radiograph may be useful especially in situations of clinically confirmed cases but with confusing laboratory results. Further, inclusion of non-responders which constitutes 30 per cent of the total HCWs at the two study centers could probably alter the disease pattern.

The primary concerns of the NTCP in many resourced-poor countries with high burden of TB are failure to meet case detection and drug treatment targets19. Nevertheless, NTCP in these countries should find ways of incorporating TB infection control interventions into their DOTS programme in other to reduce exposure of their valuable HCWs from getting occupationally-acquired TB.

Acknowledgments

This work was partly supported by the University of Ibadan, senate research grant No: SGR/COM/2006/41A awarded to the first author (AOK). Authors thank Mrs Olufunke Oluwatoba of the Department of Medical Microbiology and Parasitology, College of Medicine, University of Ibadan, Nigeria, for her assistance in data analysis.

References

- 1.Sepkowitz KA. Tuberculosis and the health care worker: a historical perspective. Ann Intern Med. 1994;120:71–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-120-1-199401010-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blumberg HM. Tuberculosis infection control in health care settings; . In: Lautenbach E, Woeltje K, editors. Practical handbook for health care epidemiologists. New Jersey: Slack Incorporated; 2004. pp. 259–73. [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. Guidelines for the prevention of tuberculosis in health care facilities in resource-limited settings WHO, Geneva. 1999. WHO/TB/99.269 Available from: www.who.int/tb/publications/whotb99269/en/index/html .

- 4.Jones-Lopez EC, Ellner JJ. Tuberculosis infection among HCWs. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2005;9:591. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blumberg HM, Watkins DL, Berschling JD, Antle A, Moore P, White N. Preventing the nosocomial transmission of tuberculosis. Ann Intern Med. 1995;122:658–63. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-122-9-199505010-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.96. Vol. 2. Abuja, Nigeria: Federal Government of Nigeria; 2009. Federal Republic of Nigeria Official Gazette. Legal notice of publication of 2006 census final results; pp. 38–9. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Enarson DA. Laboratory diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis. In: Enarson DA, editor. Management of tuberculosis. a guide for low income countries. 5th ed. Paris: International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Diseases; 2000. pp. 1–50. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saito H, Hiramine S, Watanabe T. Isolation of tubercle bacteria using Ogawa egg medium modified by addition of Tween 80. Zentralbl Bakteriol (Orig A) 1978;242:132–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barrow GI, Feltham RKA. Manual for the identification of medical bacteria. In: Cowan ST, Steel KJ, editors. Manual for the identification of medical bacteria. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1995. pp. 91–3. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Joshi R, Reingold AL, Menzies D, Pai M. Tuberculosis among health-care workers in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e494. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Claessens NJ, Gausi FF, Meijnen S, Weismuller MM, Salaniponi FM, Harries AD. High frequency of tuberculosis in households of index TB patients. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2002;6:266–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gilpin TP, Hammond M. Active case-finding-for the whole community or for tuberculosis contacts only? S Afr Med J. 1987;72:260–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Salami AK, Oluboyo PO. Health care workers and risk of hospital-related tuberculosis. Niger J Clin Pract. 2008;11:32–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.2nd ed. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2004. World Health Organization. Toman's tuberculosis case detection, treatment and monitoring: questions and answers. WHO/HTM/TB/2004.334. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oludiran KA, Eziuka OR, Mayowa IO, Ajani BR, Kikelomo O. Bacteriology of childhood tuberculosis in Ibadan, Nigeria: a five-year review. Trop Med Health. 2008;36:127–30. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Geneva: World Health Organization; 2006. World Health Organization. Guidance for national tuberculosis programmes on the management of tuberculosis in children. WHO/HTM/TB/2006.371. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Menzies D, Joshi R, Pai M. Risk of tuberculosis infection and disease associated with work in health care settings. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2007;11:593–605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meier T, Eulenbruch HP, Wrighton-Smith P, Enders G, Regnath T. Sensitivity of a new commercial enzyme-linked immunospot assay (T SPOT-TB) for diagnosis of tuberculosis in clinical practice. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2005;24:529–36. doi: 10.1007/s10096-005-1377-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morrison J, Pai M, Hopewell PC. Tuberculosis and latent tuberculosis infection in close contacts of people with pulmonary tuberculosis in low-income and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2008;8:359–68. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(08)70071-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]