Abstract

Background:

With a rapidly increasing population of older aged people, epidemiological data regarding the prevalence of mental and physical illnesses are urgently required for proper health planning. However, there is a scarcity of such data from India.

Aims:

To study the frequency and pattern of psychiatric morbidity present and the association of physical illness with psychiatric morbidity in an elderly urban population.

Settings and Design:

Cross-sectional, epidemiological study.

Materials and Methods:

All the consenting elderly persons in a municipal ward division (n=202) were enrolled after surveying a total adult population of 7239 people. A door to door survey was undertaken where the participants were interviewed and physically examined. General Health Questionnaire-12, Mini Mental State Examination, CAGE Questionnaire and Geriatric Depression Scale were used in the interview apart from consulting the available documents. Other family members were also interviewed to verify the information.

Statistical Analysis:

Chi-square test with Yates correction.

Results:

Psychiatric illnesses were detected in 26.7% while physical illnesses were present in 69.8% of the population surveyed. Predominant psychiatric diagnoses were depressive disorders, dementia, generalized anxiety disorder, alcohol dependence and bipolar disorder. The most common physical illness was visual impairment, followed by cardiovascular disease, rheumatic illnesses, pulmonary illnesses, hearing impairment, genitourinary diseases and neurological disorders. Presence of dementia was associated with increased age, single/widowed/separated status, nuclear family, economic dependence, low education, cardiovascular disorders, rheumatic disorders and neurological disorders. Depression was associated with female sex, single/widowed/separated status, staying in nuclear families, economic dependence on others and co-morbid physical illnesses, specifically cardiovascular disorders and visual impairment.

Conclusions:

This study presented a higher rate of dementia and old age depression. The interesting association with several sociodemographic factors as well as physical illnesses may have important implications for health planning.

Keywords: Dementia, epidemiology, geriatric depression, mental health

INTRODUCTION

A robust growth in the number of elderly people in the general population in recent years is termed as “greying of the world”. Population ageing is the result of a process known as demographic transition, in which there is a shift from high mortality/high fertility to low mortality/low fertility, resulting in an increased proportion of older people in the total population. India is presently undergoing such a demographic transition. The life expectancy in India has almost doubled from 32 years in 1947 to 63.4 years in 2002.[1] In the elderly, mental disorder is a key factor affecting the use of acute hospital beds, the need for residential care and the demand upon domiciliary services. Conditions such as dementia, depression and anxiety disorders influence decisions as to whether or not physical illness can be managed at home; they determine the capacity for self-care and the ability to perform daily tasks of life and, because of the practical and emotional burden imposed upon the family members, they may lead to institutionalization or heavy investment in domiciliary services.

Epidemiological data about this population is still scarce, despite a few studies conducted in the recent past.[2–5] Most of these studies were either part of general population studies or based on hospitalized or primary care geriatric patients rather than community based, which would have given a truer picture of the extent of geropsychiatric burden. Also, these studies widely differed in their methodology, and this heterogeneity has given a conflicting picture of the problem in an Indian scenario. In most of the Indian studies, 60 years was the cut-off age for the elderly against 65 years in international studies, making comparison difficult. With this background, we undertook the present study to take a close look at the real extent of psychiatric morbidity among the elderly population residing in an urban area in India, using age-appropriate screening measures[6] and by taking 65 years as the cut-off age as in international studies. In addition, we also studied the pattern of association of physical illness with psychiatric morbidity in the above sample.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study was carried out in Part two division of ward no 6 (Wanowarie Bazaar and surrounding areas) of Pune cantonment, which comes under Pune district of Maharashtra state. It is an urban area and the total adult population (18 years and above) of ward no six was 7239 as per the latest electoral rolls. This ward is divided into four parts or divisions, and this study was conducted in part II division of this ward. This particular area was chosen because it was already a field research area of the coordinating institute. The total number of the adult population (18 years and above) residing in this area was 1965, of which 218 persons were aged 65 years and above. A cross-sectional survey was carried out to study the prevalence of psychiatric morbidity among the elderly from August 2002 to May 2003. The study was approved by the institutional ethical committee.

Of the total 218 elderly, 14 could not be included in the study as they could understand neither Hindi nor English. Two more could not be included in the study as the individuals or their family members refused to be part of the study. Thus, a total of 202 were finally included in the study. All the 16 persons excluded were claimed to be psychiatrically healthy and not on any psychiatric treatment, as per individuals and their family members. Anybody who was institutionalized, unwilling or unable to understand Hindi or English was excluded from the study.

A structurally designed proforma incorporating relevant aspects was prepared, pretested and finalized with suitable modifications. The following screening instruments were used in the study:

General health questionnaire-12

The GHQ is a self-administered screening test, which is the most commonly used screening instrument for detecting psychiatric disorders in community settings and nonpsychiatric clinical settings.[7] From the number of versions available, the General health questionnaire-12 (GHQ 12)[7] item scale, which is the most commonly used version world wide, was used in this study.[6]

Mini mental state examination

The Mini mental state examination (MMSE)[8] is the most widely used cognitive screening instrument worldwide.[8] The Hindi translation of MMSE that was suitably modified was used in this study, which has been validated in various studies.[9–11]

Geriatric depression scale-15 (short version)

The Geriatric depression scale (GDS), which is a self-report scale for assessing depression, was developed by Yesavage et al. in 1983.[12] The 15-item scale, which is the most common version currently used, was used in this study.[13] The scale has three subscales: (a) a generalized anxiety (GA) scale adapted from the CARE schedule, the Present State Examination (PSE)[14] and the Geriatric Mental State (GMS),[15] (b) a Phobic (Ph) scale and (c) a Panic Disorder (PD) scale.

CAGE questionnaire

The CAGE questionnaire[16] was developed as a brief screen for significant alcohol problems in a variety of settings, which then can be followed-up by clinical enquiry. CAGE achieves excellent sensitivity and fair to good specificity.[16]

Initial contact with the community was established through the medico social workers of the institute who regularly conduct mobile medical clinics in Wanowarie Bazaar. Subsequently, familiarizing visits were made with the help of the initial contacts made in the community and a few ex-servicemen residing in the community to establish rapport with the local community. A pilot study was first carried out initially in the Wanowarie Bazaar to further refine the methodology. The pilot study demonstrated that at least two sittings were required for completion of evaluation of each individual as the elderly subjects found the study to be tiring and exhaustive. Finally, a full institutional ethical committee and review board approved the methodological and ethical issues in the final research protocol.

All the families residing in the place of study were visited and households with persons aged 65 years and above were listed. During the period of the study, at least two visits were made to each selected household. Informed consent was taken from each individual included in the study as well as from one responsible member from his/her families. Composition of the families, age of the members and other sociodemographic details recorded were verified from the available documents like ration cards and also from the head of the family or any other responsible member.

Participants were interviewed according to the study protocol and physical examination was carried out. In case of any difficulty in communication, help of other members of the family and medico social workers was used. A brief mental state examination was carried out in all subjects. After administration of screening measures, those who were found to have a probable psychiatric morbidity were subjected to a detailed mental state examination to confirm the presence of a psychiatric disorder. Diagnosis was made on the basis of ICD-10 Diagnostic Research Criteria.[17] The collected data were tabulated and analyzed using the chi-square test with Yates correction.

RESULTS

Sample characteristics

The mean age was 73.9 years. The maximum number of elderly (37.6%) in the present study was in the youngest age group (65–69 years), and the number decreased with older age groups, with the least number in the oldest age group of >90 years (4%). The overall number of males and females was almost equal (male 50.9%; female 49.1%). The majority of the participants were right handed (95.5%).

Only a small percentage of participants never married (male 2.5%; female 5.4%). However, a substantial number among the married was widowed (male 20.8%; female 18.8%). 18.8% of the study population had lost one or more parent before the age of 12 years. 26.2% of the study population had no formal education. Only 7.5% had an education of above tenth standard. 73.8% was staying along with their children.

A majority were dependent, either partially (n=67; 33.2%) or completely (n=78; 38.6%), on other family members (mostly children) for financial support.

Most participants were Hindu by religion (70.3%). 85.1% (n=172) had no family history of psychiatric illness. In those with psychiatric illness among family members, substance abuse (6.4%) and depressive disorders (4.5%) were the most common complaints.

Prevalence of psychiatric illnesses

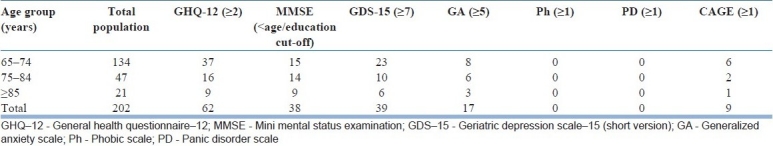

Sixty-two persons (30.69%) had scores ≥2 in GHQ-12, i.e. above the cut-off score for this screening instrument and requiring detailed evaluation for a possible psychiatric illness. Of them, 54 (26.7%) had a diagnosable mental illness. Cognitive impairment, as tested by MMSE, was present in 38 persons (18.81%). Thirty-nine subjects (19.36%) screened positive for depression. Seventeen persons screened positive for generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) (8.41%) and none for Ph and PD. Nine elderly (4.45%) were screened positive for alcohol-related disorder [Table 1]. There was a statistically significant increase in the GHQ-12 scores with increasing age (P=0.03). Similarly, there was a statistically significant decrease in the MMSE scores with increasing age (P=0.03). However, there was no statistically significant difference in scores of depression (P=0.82), anxiety (P=0.87) or alcohol abuse (P=0.99) among the different age groups.

Table 1.

Screening instrument scores

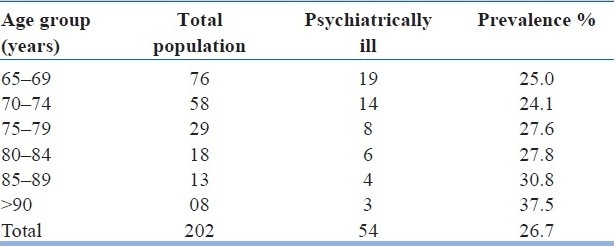

The overall prevalence of psychiatric morbidity in this geriatric population was 26.7%. The most prevalent psychiatric disorder was depressive disorders (n=33; 16.3%), followed by dementia (n=30; 14.9%), GAD (n=13; 6.4%), alcohol dependence (n=8; 4%), bipolar disorders (n=5; 2.5%) and schizophrenia spectrum disorders (n=3; 1.5%). Prevalence of psychiatric disorders in the various age groups is given in Table 2. A definite trend of increase in the prevalence of psychiatric disorders with increasing age was noted, although this was not statistically significant (chi-square [65–74 years; 75–84 years; ≥85 years] 0.99, df 2, P=0.6082; not significant).

Table 2.

Prevalence of psychiatric disorders

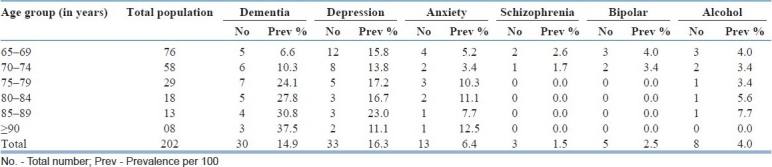

The distribution of psychiatric disorders in different age groups is shown in Table 3. The most prevalent psychiatric disorder was depressive disorders (16.3%), followed by dementia (14.9%), anxiety disorders (generalized anxiety) (6.4%), alcohol related (4%), bipolar disorders (2.5%) and schizophrenia spectrum disorders (1.5%). Analysis revealed that there is a highly statistically significant increase in the prevalence of dementia with increasing age (x2=14.59; P=0.00). There is a statistically significant decrease in the prevalence of schizophrenic disorders with advancing age (x 2 =6.26; P=0.04). The other disorders did not show any statistically significant differences in the prevalence among the different age groups. Seven patients with depression and four patients with dementia gave a history of excessive alcohol consumption in the past, but none met the criteria for alcohol dependence or harmful use at the time of the study. Three patients with dementia and two with depression gave a history of psychotic symptoms in the past.

Table 3.

Type of psychiatric disorders with age

Females had more depressive disorders compared with males (x2=4.92; P=0.02), whereas alcohol-related disorders were present exclusively in males (x2=8.01; P=0.00). Gender difference was not evident in any other disorders.

There was a statistically significant association between education status and prevalence of dementia; those who have had at least middle school education had a lesser prevalence of dementia (x2=5.03; P=0.02). There was no statistically significant association between other disorders and education.

There was a statistically significant increase in the prevalence of dementia in the elderly who were not living with their spouses (x2=4.34; P=0.03). Married persons also had a lesser prevalence of depression (x2=11.46; P=0.09). On the other hand, depressive disorders were common with nuclear family type (x2=7.73; P=0.02). However, no such association was found with any other psychiatric disorder.

Statistically significant association was found between family history of nonaffective psychotic illness and presence of schizophrenia (x2=21.1; P=0.04). Family history of affective psychoses showed a trend of association with bipolar disorders in probands (x2=12.0; P=0.07). Similarly, family history of substance disorders was associated with the presence of alcohol-related disorders, although the association was not statistically significant (x2=4.77; P=0.08).

Patients suffering from dementia (x2=13.3; P=0.001), depression (x2=3.88; P=0.04) and bipolar disorder (x2=8.15; P=0.01) were significantly dependent on the family members economically. However, this was not evident in case of the other psychiatric disorders.

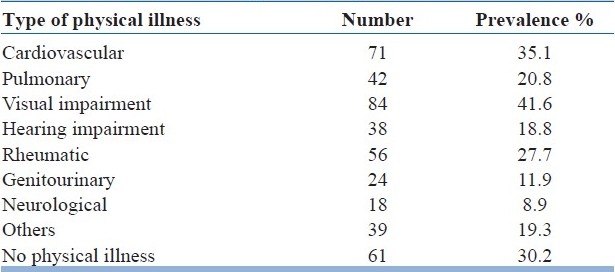

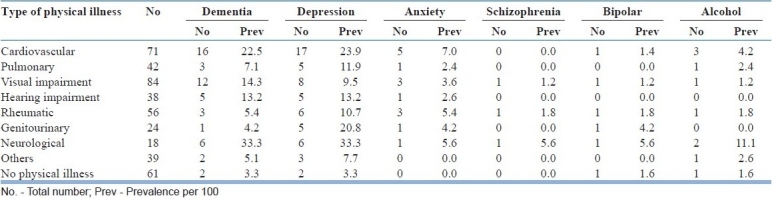

Prevalence of physical illnesses

One or more physical illnesses were present in 69.8% of the subjects. The most common morbidity was visual impairment, followed by cardiovascular disease, rheumatic illnesses, pulmonary illnesses, hearing impairment, genitourinary diseases and neurological disorders. There were significantly more physical illnesses in subjects who had dementia (x2=4.72; P=0.02), depression (x2=5.72; P=0.01) and anxiety disorders (x2=3.67; P=0.04) compared with others [Table 4].

Table 4.

Types of physical illness

Relation of psychiatric disorders and physical illness is shown in Table 5. Further analysis revealed significantly more cardiovascular disorders in persons with dementia (x2=5.11; P=0.02) and depression (x2=4.64; P=0.03). The prevalence of visual impairment was found in subjects with depressive disorders (x2=4.88; P=0.02). A trend of more visual impairment was evident in persons with alcohol dependence (x2=2.90; P=0.08). Significantly more rheumatic disorders was present in subjects with dementia (x2=5.52; P=0.01). Significantly more neurological disorders were also seen in subjects with dementia (x2=5.21; P=0.03). No statistically significant association was found between prevalence of any psychiatric disorder and hearing impairment, pulmonary disorders or genitourinary disorders.

Table 5.

Relation of psychiatric disorders with physical illness

DISCUSSION

Examining an urban elderly population, this study came out with certain important findings. The prevalence of geriatric psychiatric disorders was 26.7%, which was slightly less than the 32.2–43.3% prevalence reported in other Indian studies.[5,18,19] Cognitive impairment according to MMSE was present in 18.81% of the persons while 14.9% of them were diagnosed as having dementia. The prevalence of dementia and cognitive impairment was slightly more compared with the 1.6–10% prevalence of dementia reported in other Indian studies.[4,18,19] The higher prevalence of cognitive disorders in our study can be explained by the higher cut-off age of 65 years for inclusion in the study. As older persons were examined, the prevalence of cognitive problems also probably increased. Indeed, this study documented a statistically significant decrease in MMSE scores with increasing age. It is well known that prevalence of dementia almost doubles with every 5-years increase in age.[20]

Apart from increased age, other factors associated with dementia in this study were not having a spouse at present, nuclear family type and economic dependence on others. It will be interesting to examine their interaction in determining the course and outcome of dementias. Evidently, these factors lead to a lack of social support as well as a sense of insecurity, which may have important effects on the quality of life of such patients. There was a statistically significant association between educational status and prevalence of dementia. The prevalence of dementia progressively decreased with increasing standard of education. Studies have consistently shown that risk for dementia and cognitive impairment are higher in elderly persons who have had little or no education, and education has been proposed as a protective factor for cognitive disorders.[20]

There was high co-morbidity with physical illnesses, specifically cardiovascular disorders, rheumatic disorders and neurological disorders. Prospective studies are required to examine the exact nature of these associations. The overall prevalence of dementias has been reported to be the same in men and women,[20] as in this study.

Depression was present in 16.3% of the population, which is similar to a 13.3–18.3% prevalence reported in the literature.[21–23] The prevalence rates in Indian studies have been unfortunately widely varied, ranging from 6%[24] to 55.2%.[4] The risk factors associated with depression in this study were: female sex, not staying with spouse due to separation or death of spouse or never being married, staying in nuclear families, economic dependence on others and co-morbid physical illnesses, specifically cardiovascular disorders and visual impairment. Extended families, married status and economic independence evidently act as a protective factor against developing depression in vulnerable elderly individuals. Physical disability has been consistently found to be a risk factor for depression in late life.[25]

Only 2.5% had a diagnosis of bipolar mania. Few studies have so far explored bipolar mania in the elderly, which report a wide rage of prevalence from 0.4%[19,26] to 7.5%.[4]

In the present study, 6.4% of the persons had GAD, which is similar to the 4.6% prevalence rate reported by Ritchie et al. (2003).[26] Interestingly, no panic disorder, phobia or obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) were detected in our study. Most Indian researchers reported a low prevalence of anxiety disorders in the elderly population.[4,18,24] Only three persons (1.5%) suffered from schizophrenia, which is similar to the findings reported in other studies.[4,19,26–28]

The prevalence of alcohol dependence in our study was 4%. This is similar to a 3.7% prevalence reported in the urban Indian elderly population.[5] Male sex, family history of substance disorders and visual impairment were associated with alcohol disorders in our study. While male predisposition and positive family history is common in alcohol-related disorders, it is the association with visual impairment that raises concern. Whether the “country liquor,” the most common form of alcohol consumed in India, has any role in it needs to be examined. “Hooch tragedies” by consuming improperly distilled "country liquor" are common in India, which frequently results in optic neuropathy and loss of vision.

Presence of dementia, depression and bipolar disorders was significantly associated with economic dependence on others. This may be due to their decreased capability of earning due to illness or the prevalent social stigma against mental illness. Future studies need to explore these issues.

Prevalence of physical illness in this sample was 69.8%, which was similar to the 68–74% prevalence reported in India.[5,29] Visual impairment was the most common physical illness in our study, which is supported by the Indian literature.[24,30] Prevalence of physical illness increased with advancing age. At least one physical illness was observed in 87.5% of the persons of the ≥90 years age group.

Subjects with dementia and depressive disorders had a significantly higher prevalence of cardiovascular disorders. Subjects with dementia also had a high prevalence of neurological disorders. Association of dementia with neurological and cardiovascular disorder may be explained by the occurrence of vascular dementia. Whether depression is a psychological reaction to a serious physical illness or due to undiagnosed cerebral accidents common in cardiovascular disorder patients is uncertain. Similarly, a significant association of rheumatic disorders with dementia may indicate a potent area for future research. Studies have shown that physical illness, depression and dementia are three important independent predictors of suicide. Association of physical illness with depression and dementia may make the elderly population particularly vulnerable to suicide.

The present study confirms the findings of the earlier studies, in that a significant proportion of the elderly population in the community has psychiatric illnesses. Apart from cognitive impairment, this study also showed a high prevalence of depression in the elderly. Geriatric depression tends to get neglected often, and this study points to the importance of screening for depression routinely in practice. This study also showed the prevalence rates of other psychiatric disorders such as anxiety disorders, schizophrenia and alcohol-related disorders, on which little data is available in the elderly in India at present.

The majority of the subjects with psychiatric morbidity were not taking any psychiatric treatment at the time of the study. Sadly, their family members often did not consider it necessary to seek treatment for them. Lack of awareness about geriatric psychiatric illnesses and, especially dementia, in an urban area of a prominent Indian city points to the state of affairs regarding awareness about geriatric mental health in India. Urgent concerted steps are required at various levels of administration to bring awareness and provide interventions to alleviate the disability and suffering of the individual, their family members and the community in general.

Limitations

Inclusion of only those individuals who can understand English or Hindi

Relatively small study population, being a community survey

The three subcategories of the population not matched and hence conclusions difficult to draw

Study does not fulfil strict criteria of epidemiological studies in the elderly as laid out by Ganguli et al.[10]

CONCLUSION

The prevalence of psychiatric morbidity in the elderly population of this study is quite high, with a trend for increase in prevalence for cognitive impairment with advancing age. The most prevalent psychiatric disorder was depressive disorders, followed by dementia, generalized anxiety disorders, alcohol-related disorders, bipolar disorders and schizophrenia spectrum disorders. The prevalence of comorbid physical disorders was also high, with a trend in increase in prevalence with increasing age.

With more studies like the current study, in the community-dwelling elderly, it is hoped that a truer picture of psychiatric morbidity in the elderly in India will emerge and lead to a substantial overhaul in the current delivery of care to these individuals, whose wellness and disability play a major role in determining the health and wellbeing of the society in general.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.UN population Division: World population prospects, the 2000 revision. New York: United Nations publication; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rao AV. Psychiatric morbidity in aged. Indian J Med Res. 1997;106:361–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prasad KM, Sreenivas KN, Ashok MV. Psychogeriatric patients.A sociodemographic and clinical profile. Indian J Psychiatry. 1996;38:178–81. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nandi PS, Banerjee G, Mukherjee SP, Nandi S, Nandi DN. A study of psychiatric morbidity of the elderly population of a rural community in West Bengal. Indian J Psychiatry. 1997;39:122–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mallik AN, Chatterjee AN, Pyne PK. Health status among elderly people in urban setting. Indian J Psychiatry. 2001;43:41. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burns A, Lawlor B, Craig S. Rating scales in old age psychiatry. Br J Psychiatry. 2002;180:161–7. doi: 10.1192/bjp.180.2.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goldberg DP, Williams P. A user's Guide to the General Health Questionnaire. Windsor: BFER-Nelson; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, Mellugh PR. Mini-Mental State: A practical method for grading the cognitive states for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:389–98. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ganguli M, Ratcliff G, Chandra V, Sharma S, Gilby J, Pandav R, et al. A Hindi version of the MMSE: The development of a cognitive screening instrument for a largely illiterate rural elderly population in India. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1995;10:367–77. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ganguli M, Chandra V, Gilby JE, Ratcliff G, Sharma SD, Pandav R, et al. Cognitive test performance in a community based non demented elderly sample in rural India: The Indo-US cross national dementia epidemiology study. Int Psychogeriatr. 1996;8:507–24. doi: 10.1017/s1041610296002852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pandav R, Fillenbaum G, Ratcliff G, Dodge H, Ganguli M. Sensitivity and specificity of cognitive and functional screening instruments for dementia: The Indo-US cross national dementia epidemiology study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50:554–61. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50126.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yesavage JA, Brink TL, Rose TL, Lum O, Huang V, Adey M, et al. Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale.A preliminary report. J Psychiatr Res. 1983;17:37–49. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(82)90033-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sheikh J, Yesavage J. Geriatric Depression Scale; recent findings in development of a shorter version. In: Brink J, editor. Clinical Gerontology: A Guide to Assessment and Intervention. New York: Howarth Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wing JK. A technique for studying psychiatric morbidity in in-patient and out-patient and in general population samples. Psychol Med. 1976;6:665–71. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700018328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Copeland JR, Kelleher MJ, Kellett JM, Gourlay AJ, Gurland BJ, Fleiss JL, et al. A semi structured clinical interview for the assessment of diagnosis and mental state in the elderly: The Geriatric Mental State Schedule.I: Development and reliability. Psychol Med. 1976;6:439–49. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700015889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blacker D. Psychiatric rating scales. In: Kaplan HI, Sadock BJ, editors. Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry. Baltimore MD: Williams and Wilkins; 2000. p. 774. [Google Scholar]

- 17.The ICD -10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders: Diagnostic Criteria for Research. Geneva: WHO; 1993. WHO. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ramachandran V, Menon MS, Murthy BR. Psychiatric disorders in subjects aged over fifty. Indian J Psychiatry. 1979;22:193–8. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tiwari SC. Geriatric psychiatric morbidity in rural northern India: Implications for future. Int Psychogeriatr. 2000;12:35–48. doi: 10.1017/s1041610200006189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Henderson AS. Geneva: WHO; 1994. Epidemiology of mental disorders and psychosocial problems: Dementia. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lindesay J, Briggs K, Murphy E0. The Guy's / Age concern survey: Prevalence rates of cognitive impairment, depression and anxiety in an urban elderly population. Br J Psychiatry. 1989;155:332–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Beekman AT, Copeland JR, Prince MJ. Review of community prevalence of depression in later life. Br J Psychiatry. 1999;174:307–11. doi: 10.1192/bjp.174.4.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Livingston G, Leavey G, Kitchen G, Manela M, Sembhi S, Katona C. Mental health of migrant elders – the Islington study. Br J Psychiatry. 2001;179:361–6. doi: 10.1192/bjp.179.4.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rao AV, Madhavan T. Geropsychiatric morbidity survey in a semi-urban area near Madurai. Indian J Psychiatry. 1982;24:258–62. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cole MG, Dendukuri N. Risk factors for depression among elderly community subjects: A systemic review and meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:1147–56. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.6.1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ritchie K, Artero S, Beluche I. Prevalence of DSM IV psychiatric disorder in the French elderly population. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;184:147–52. doi: 10.1192/bjp.184.2.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Regier DA, Farmer ME, Rae DS, Myers JK, Kramer M, Robins LN, et al. One-month prevalence of mental disorders in the United States and sociodemographic characteristics: The Epidemiologic Catchment Area study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1993;88:35–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1993.tb03411.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Copeland JR, Dewey ME, Wood N. Range of mental illness among the elderly in the community: Prevalence in Liverpool using GMS-AGECAT package. Br J Psychiatry. 1987;150:815–23. doi: 10.1192/bjp.150.6.815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pereira YD, Estibeiro A, Dhume R, Fernandes J. Geriatric patients attending tertiary care psychiatric hospital. Indian J Psychiatry. 2002;44:326–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barari DC. Integrated health care and allied services for the elderly: some perspectives. In: Kumar V, editor. Aging: Indian Perspective and Global Scenario. New Delhi: AIIMS; 1996. pp. 102–4. [Google Scholar]