Abstract

Context:

Migraine and tension type headache (TTH) are two most common types of primary headaches. Though the International Classification of Headache Disorders-2 (ICHD-2) describes the diagnostic criteria, even then in clinical practice, patients may not respect these boundaries resulting in the difficulty in diagnosis of these pains.

Materials and Methods:

This cross-sectional study involved 50 subjects in each of the two groups – migraine and TTH – after screening for the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Diagnosis was made according to the ICHD-2 criteria. Their clinical history was taken in detail and noted in a semi-structured performa. They were examined for the presence of a number of factors like pericranial tenderness and muscle parafunction. Statistical analysis was done with the help of SPSS v 11.0. To compare the non-parametric issues, chi-square test was run and continuous variables were analyzed using independent sample t test.

Results:

In general, migraineurs had progressive illness (χ2=9.45; P=0.002) with increasing severity (χ2=21.86; P<0.001), frequency (χ2=8.5; P=0.04) and duration of each headache episode (χ2=4.45; P=0.03) as compared to TTH subjects. Along with the headache, they more commonly suffered orthostatic pre-syncope (χ2=19.94; P<0.001), palpitations (42%vs.18% among TTH patients; χ2=6.87; P=0.009), nausea and vomiting (68% vs. 6% in TTH; χ2=41.22; P<0.001, and 38% vs. none in TTH; χ2=23.45, P<0.001, respectively), phonophobia (χ2=44.98; P<0.001), photophobia (χ2=46.53; P<0.001), and osmophobia (χ2=15.94; P<0.001). Their pain tended to be aggravated by head bending (χ2=50.17; P<0.001) and exercise (χ2=11.41; P<0.001). Analgesics were more likely to relieve pain in migraineurs (χ2=21.16; P<0.001). In addition, post-headache lethargy was more frequent among the migraineurs (χ2=22.01; P<0.001). On the other hand, stressful situations used to trigger TTH (χ2=9.33; P=0.002) and muscle parafunction was more common in TTH patients (46% vs. 20%; χ2=7.64; P=0.006). All the cranial autonomic symptoms were more common in migraineurs as compared to TTH subjects (conjunctival injection: χ2=10.74, P=0.001; lacrimation: χ2=17.82, P<0.001; periorbital swelling: χ2=23.45, P<0.001; and nasal symptoms: χ2=6.38, P=0.01).

Conclusion:

A number of symptoms that are presently not included in the ICHD-2 classification may help in differe-ntiating the migraine from the TTH.

Keywords: Migraine, symptoms, tension type headache

INTRODUCTION

Headache is an important accompaniment with a number of psychiatric illnesses.[1–4] It has been also reported that in subjects with moderate to severe depression, it is more likely to progress toward chronification.[5] Hence, psychiatrists tend to see a number of headache patients and exact diagnosis is required for the proper management of the patient. Though the International Headache Society had proposed clear criteria for differentiating them, in clinical conditions it may sometimes be very difficult to differentiate between them.[6–7] A number of factors defying the International Classification of Headache Disorders-2 (ICHD-2) criteria pose obstacles, for example, the migraine may be bilateral, may not be having classical pulsating pain during the acute attack, and may be sometimes devoid of nausea, vomiting, phonophobia and photophobia.[6,8] On the other hand, tension type headache (TTH) may present with throbbing pain, phonophobia, nausea, vomiting and may be unilateral.[8,9]

In addition, migraine pain usually takes time to evolve and initial features of its attack may mimic that of TTH and dilemma worsens further with the use of analgesics.[8]

Attempts have been made to clinically differentiate migraine from TTH in the past. These studies assessed the factors that are not included in ICHD-2. Unalp et al. reported that TTH in adolescents presents with temporal pain and there is a frequent history of TTH in siblings while migraineurs show more school absenteeism.[10] Mongini et al. suggested that McGill Pain Questionnaire may be used to differentiate them. They found that pain scores were higher in migraine as well as chronic migraine group as compared to episodic TTH and chronic TTH group, respectively.[11] Zivadinov et al. suggested that precipitating factors differ for both of these headaches – stress for migraine and physical activity for TTH.[12] Port-Etesaam et al. reported that osmophobia may be used to differentiate migraine and TTH as it is seen only in the former cases.[13] Despite these attempts, opinion differs, and considering these overlapping features of both these headaches, one study has suggested that migraine and TTH may lie on the same continuum.[14]

In short, despite the availability of ICHD-2 criteria, it is important to find out other clinical symptoms that can help us in differentiating the migraine without aura from TTH. This study was planned to address this issue.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Fifty consecutive subjects suffering from migraine and 50 consecutive subjects of TTH meeting the inclusion criteria were recruited from the headache clinic of a teaching hospital after screening for the exclusion criteria. The study was approved by the institutional ethics committee and informed consent was obtained from all the study subjects. Migraine and TTH were diagnosed according to the ICHD-2 criteria.[6] All the participants belonged to the same ethnic group and had comparable socioeconomic status.

Subjects with major neurological disorders (e.g. epilepsy, space occupying lesions, neurodegenerative disorders), those with chronic daily headache (undiagnosed or mixed type), substance use disorders (except tobacco), those taking prophylactic drugs for migraine or TTH for more than 3 weeks, subjects with co-morbid other primary headache, co-morbid psychiatric disorder, and those consuming antioxidants or multivitamins for more than a week were excluded from the study.

Patient's history of headache was taken in detail, followed by the clinical examination (general assessment including testing for pericranial tenderness through digital palpation and ascertaining muscle parafunction), and wherever required, appropriate laboratory investigations were conducted to rule out secondary headache. Parallel information was also collected from a reliable family member regarding headaches of the sufferer. All the information was recorded on a semi-structured performa. The following data were recorded in the history: total duration of symptoms, average number of headaches per month, time to attain maximum severity after the onset of pain, laterality and side of pain, location of pain (temporal, frontal, occipital, parietal, orbital, generalized, neck), radiation if any, quality of pain (aching, pulsating/throbbing, pressing, tightening, band like, etc.), average duration of episodes, usual time of onset, factors that precipitate and relieving headache, premonitory symptoms (mainly yawning), and lastly, associated symptoms to diagnose migraine (e.g. photophobia, nausea or vomiting, photophobia, worsening with exertion, dizziness, allodynia, family history of headache etc). Depending upon the laterality of headache, patients were divided into the following categories: (a) bilaterally equal headache,; bilateral headache but more severe on one side – (b) right side or (c) left side; strictly unilateral pain on- (d) right side or (e) left side; (f) unilateral headache episodes, with right side headaches more frequent than left, (g) unilateral headache with left side headaches more frequent than right, (h) unilateral left headaches more frequent than bilateral headaches, (i) unilateral right side headache more frequent than bilateral headaches, (j) bilateral headaches more frequent than unilateral right side pain, and (k) bilateral headaches more frequent than unilateral left side pain.

For the sake of analysis, three categories were made- bilateral headaches (“a” to “c”); unilateral headaches (categories “d” to “i”); and bilateral headaches more frequent than unilateral headaches (categories “j” and “k”). Based on the side of headache, two groups were made: predominantly right-sided headaches (b+d+f+i) and predominantly left-sided headaches (c+e+g+h).

Cranial autonomic symptoms

Leading questions were asked regarding occurrence of the following symptoms during the headache: conjunctival injection, lacrimation, nasal blockade or running nose, sweating on forehead and periorbital edema. In patients with these symptoms, laterality of individual cranial autonomic symptoms (CAS) was also ascertained in relation with the laterality of headache (ipsilateral or bilateral or bilateral with more intensity toward severe pain side).

Examination procedure

The clinical examination was performed according to standard methods described earlier.[15]

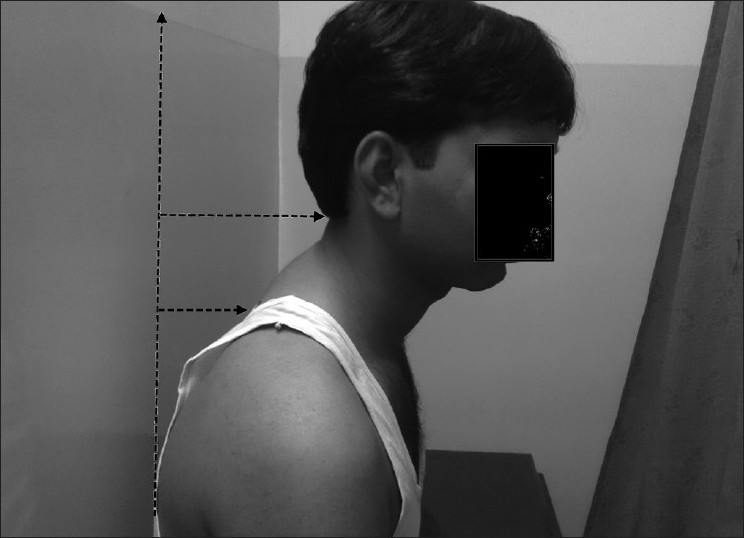

Postural examination

The patient was asked to stand straight with the legs slightly open and the posture was examined from front and lateral side. Similar maneuver was repeated with the patient in his usual sitting position. During examination from the front, the examiner's face was in line with that of the patient, and during lateral examination, examiner's face was corresponding with the spinal cord of the patient.

Pericranial tenderness

Pericranial tenderness was assessed in the sternocleidomastoid and trapezius muscles. The subject was asked to tilt his head slightly lateral with slight flexion to make the sternocleidomastoid prominent and then both its ends were palpated with the thumb and finger. Trapezius was palpated digitally with the pulp of index and middle fingers at the upper border from shoulder to neck.

Muscle parafunction

Temporalis and masseters were palpated with index and middle fingers together, both before and after clenching of teeth, and change in their volume was noted. At least twofold increase in volume was considered pathological.

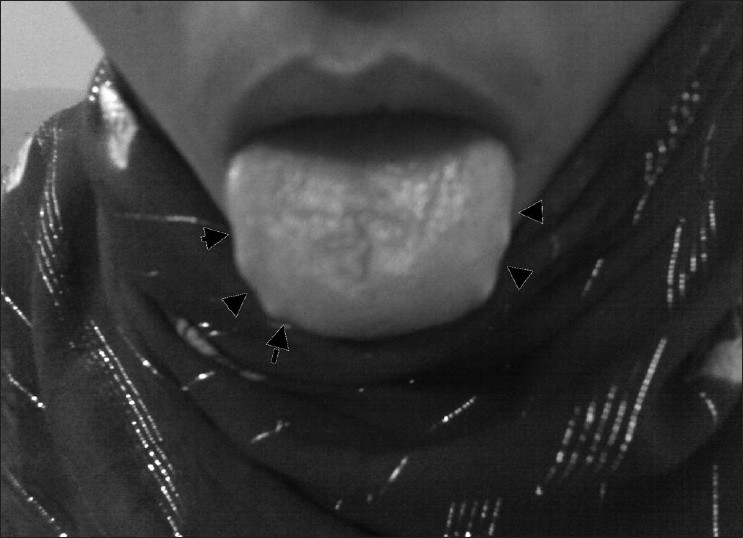

Tongue examination

Subjects were asked to protrude their tongue and indentations at its borders were examined.

Statistical analysis

Analysis was done using SPSS v 11.0 for Windows. Chi-square test was used for comparing the proportions and independent sample “t” test was used to compare numerical values between two groups.

RESULTS

Both the groups were identical with respect to average age (27.66 years among migraineurs and 27.6 years among TTH group subjects). Also, both the groups had preponderance of females (82% among migraineurs and 100% in TTH group).

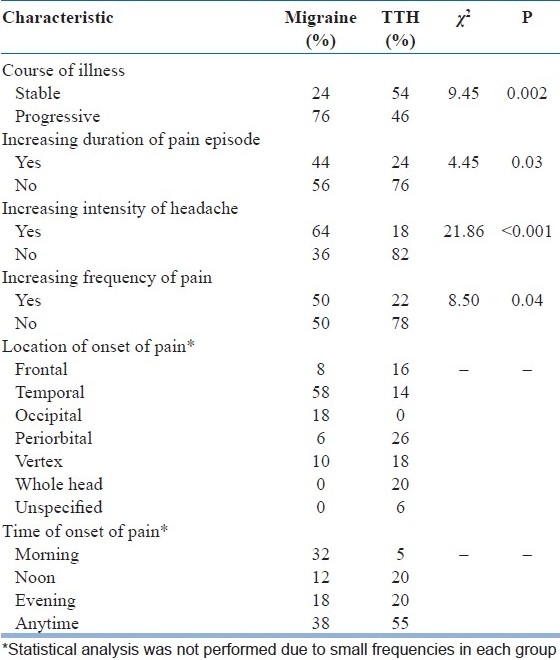

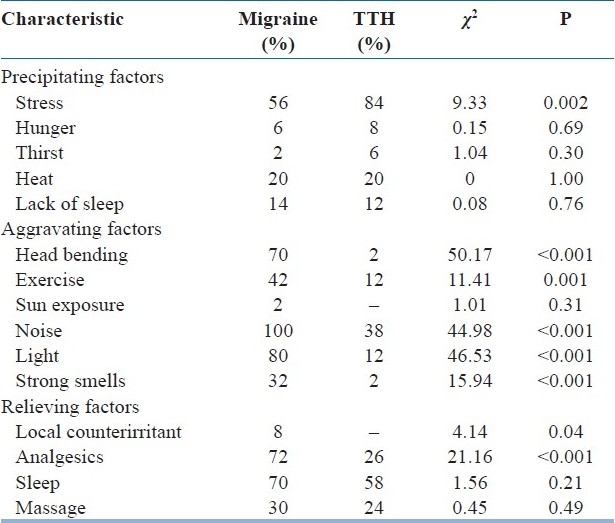

When other illness related factors were analyzed, it was found that migraine and TTH groups did not differ with regards to total duration of illness, duration since the illness had become disabling and duration of individual headache episode. However, migraineurs had more frequent headaches per month (10 episodes vs. 22 episodes of TTH; P<0.05); but in them, headache took more time to reach the maximal severity (1.36 hours vs. 0.30 hour in TTH patients; P<0.05). Other illness related factors are depicted in Table 1. Comparison of precipitating, aggravating and relieving factors in both groups is shown in Table 2. Figure 1 compares the laterality of both headaches.

Table 1.

Headache characteristics in migraineurs and tension type headache groups (n=50 in each group)

Table 2.

Precipitating, aggravating and relieving factors among migraineurs and TTH group (n=50 in each group)

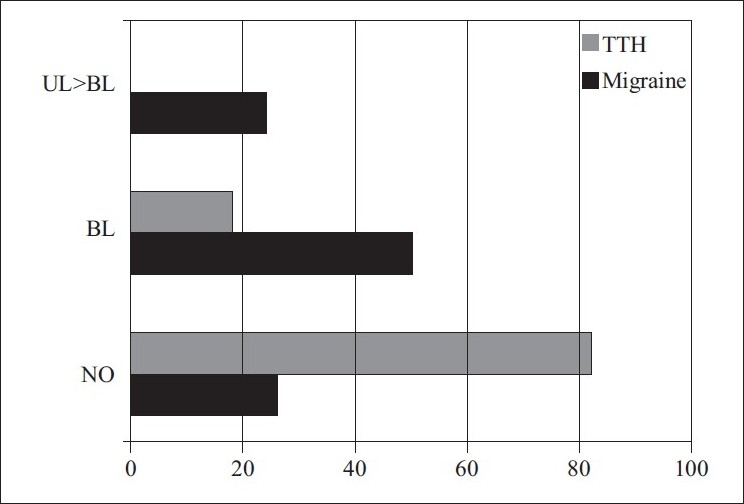

Figure 1.

Laterality of cranial autonomic symptoms among migraineurs and TTH subjects

Few non-pain symptoms were also associated with these headaches. These symptoms were not directly related to the trigeminal nucleus complex, but are known to accompany these types of headaches. Nausea and vomiting were more frequent among migraineurs (68% vs. 6% in TTH, χ2=41.22, P<0.001; and 38% vs. none in TTH, χ2=23.45, P<0.001, respectively).

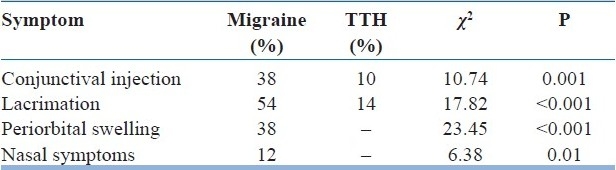

Symptoms of trigemino-autonomic pathway stimulation were also seen in these groups. 56% migraineurs complained of blurred vision co-occurring with headache, whereas it was seen in 44% TTH patients also (χ2=1.44; P=0.23). Other autonomic symptoms were also complained by these patients [Table 3]. 54% migraineurs complained of orthostatic pre-syncope associated with headache, whereas it was reported by 12% of TTH patients only (χ2=19.94; P<0.001). Similarly, palpitations during headache were more frequent among migraineurs (42% vs. 18% among TTH patients; χ2=6.87; P=0.009).

Table 3.

Prevalence of cranial autonomic symptoms among migraineurs and tension type headache group (n=50 in each group)

Scalp allodynia was reported by 70% patients in each group. After the headache, 40% of migraineurs felt lethargic and 14% used to feel sleepy, while only 2% of TTH subjects suffered each of these symptoms (χ2=22.01; P<0.001). Family history of primary headache was reported by 26% of migraineurs versus 14% of TTH subjects (χ2=2.11; P=0.34).

On examination, Muscle parafunction was commoner among TTH patients as compared to migraineurs (46% vs. 20%; χ2=7.64; P=0.006) [Figure 2]. Pericranial tenderness was seen in 54% migraineurs versus 44% TTH subjects (χ2=1.00; P=0.31). Neck posture at the relaxed sitting position was normal in 78% migraineurs as compared to 84% TTH patients [Figure 3]. On oral examination, indentations on the lateral margins of tongue were seen in 30% migraineurs versus 44% TTH subjects (χ2=4.59; P=0.10) [Figure 4].

Figure 2.

Muscle parafunction in headache patients

Figure 3.

Posture problems in headache patients

Figure 4.

Serrated tongue in headache patients

DISCUSSION

In short, this study has revealed important differences between migraine and TTH. Migraineurs had progressive illness with increasing severity, frequency and duration of each headache episode as compared to TTH subjects; in other words, they were moving toward chronification.

Along with the headache, they more commonly suffered orthostatic pre-syncope, palpitations, nausea, vomiting, phonophobia, photophobia, and osmophobia. Their pain tended to be aggravated by head bending and exercise. Analgesics were more likely to relieve pain in migraineurs. Similarly, CAS were more likely to be seen in migraineurs. In addition, post-headache lethargy was more frequent among the migraineurs.

On the other hand, stressful situations used to trigger TTH and muscle parafunction was more common in TTH patients. Even though a few TTH subjects did show CAS, they were never lateralized. Hence, these factors may be used to differentiate both the headaches from each other.

This study suggests that migraine is more likely to progress over time in terms of frequency, severity and illness as compared to TTH. This suggests that migraine is more likely to be complicated then TTH. Chronic migraine is considered as a complication of the episodic migraine and likely to evolve owing to multiple factors.[16,17] These factors may include associated illnesses and frequency of medication overuse secondary to the intolerability of the migraine pain.[1,18] What makes the TTH worse is still an enigma and further research is required to clarify this issue.

Weather, smell, smoke and light were reported as the precipitating factors that differentiate migraine from TTH.[19] It was reported that stress was a precipitating factor for both migraine and TTH.[19] Contrary to this, we found that stress was more likely to precipitate TTH as compared to migraine. Similar results were reported by Donias et al.[20] who found that negative emotions more commonly precipitated TTH than migraine. They suggested that TTH subjects could be having different or defective cognitive schemata that process the given emotional stimuli in their own way to start the pain as compared to migraineurs. Though they had suggested that these schemata work in a stereotyped manner, this does not seem to be a case as stress did not precipitate the pain at all times as we see in clinical practice. Moreover, stress was not the precipitating factor in all TTH subjects in this study; rather, it was just more frequent in this group. Hence, this issue requires more investigation in future with improved methodology.

In concordance with the previous study,[19] our study confirms that in addition to light and noise head bending, smells and straining/exercise increase the pain in migraineurs but not in TTH subjects. Whether this can truly differentiate the TTH subjects from migraineurs is still an illusion, but our results, especially the absence of phonophobia and photophobia in TTH subjects, are consequent to the strict adherence to the ICHD-2. However, it is still not uncommon to find out the TTH subjects with these features in clinical practice and even in literature.[9] Our experience suggests that most of these TTH subjects later on develop migraine or that they have any family member suffering from migraine. This notion can be explained on the basis of modular headache theory.[21]

Osmophobia during migraine is an important symptom that has gained acceptance among the scientific community in the past.[22] A number of studies confirm its association with migraine and it is now proposed to be included in the ICHD diagnostic criteria. Similarly, orthostatic pre-syncope as well as the palpitations were more common in migraineurs. This confirms the previous reports of autonomic disturbances among these patients.[8,23,24] Why the disturbances are limited to the migraineurs and are not seen during the TTH is still an enigma and requires further research.

Analgesics were more likely to relieve migraine headache as compared to TTH. Not only the relieving factors but also the pain-relieving behavior may be used to differentiate both these headaches. Previous literature suggests that migraineurs frequently engage in a number of activities like pressing and applying cold stimuli to the painful site, trying to sleep, changing posture, sitting or reclining in bed, isolating themselves, using symptomatic medication, inducing vomiting, changing diet and becoming immobile during the attacks.[25] On the contrary, TTH patients use only the scalp massage.[25]

Until recent past, CAS were considered to be the hallmark of cranial autonomic cephalalgias.[6] Their presence was never considered important in migraine till a few reports were published emphasizing upon these symptoms.[26–29] Later on, these were also reported in TTH subjects.[30] However, during our previous study and even during the present study, we found that mostly they were only partially lateralized.[26] Unilateral symptoms were reported in a small number of migraineurs only.[26] This goes in concordance with the modular headache theory.[21,6]

Muscle parafunction was more common in the TTH subjects as compared to the migraineurs, as well as stress was more commonly a triggering factor for it. This has been reported in the past.[19,31] The muscle hypertrophy is consequent to the activation of muscles owing to the stress or it could be related to the central sensitization.[32,33] Central sensitization is known to occur in both migraine as well as TTH;[34,35] however, in this study, central sensitization was more frequent among migraineurs as compared to the TTH subjects. Cognitive stress is known to evoke muscle pain in the pericranial areas and this response differs between migraineurs and TTH subjects.[36] TTH subjects had more pain in the temporalis and frontalis, whereas migraineurs developed more pain in splenius and temporalis. Contrary to migraineurs, TTH subjects had delayed pain recovery in all muscle regions.[36] However, we did not study the regional difference in the hypertrophy in this study and this is clearly an area for future research.

However, this study has some limitations. Firstly, strict inclusion criteria in this study preclude from generalizing the results as subjects with such isolated illness are not very common in the clinics. Hence, results must be applied with caution in the general population. Secondly, sample size of the study was small relative to the prevalence of the illnesses in question owing to strict exclusion criteria. We suggest inclusion of a larger sized sample in the future studies.

In conclusion, certain symptoms not mentioned in the ICHD-2 can be used to differentiate between migraine and TTH patients.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Gupta R, Bhatia MS, Chhabra V. Chronic daily headache: Medication overuse and psychiatric morbidity. JPPS. 2007;4:19–24. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fridiani F, Villani V. Migraine and depression. Neurol Sci. 2007;28:S161–5. doi: 10.1007/s10072-007-0771-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Serrano-Duenas M. Chronic tension-type headache and depression. Rev Neurol. 2000;30:822–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marchesi C, De Ferri A, Petrolini N, Govi A, Manzoni GC, Coiro V, et al. Prevalence of migraine and muscle tension headache in depressive disorders. J Affect Disord. 1989;16:33–6. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(89)90052-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gupta R, Bhatia MS, Singh NP, Upreti R. Association of depression with headache. JPPS. 2007;4:88–91. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Headache Classification Subcommittee of the International Headache Society. The International Classification of Headache Disorders. Cephalalgia. 2004;24:1–151. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bendsten L, Jensen R. Tension Type Headache: What is new in the second edition of the International classification of headache disorders. In: Olesen J, editor. Classification and diagnosis of headache disorders. New Delhi: Oxford University Press; 2006. pp. 101–8. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lance JW, Goadsby PJ. Mechanism and management of headache. Philadelphia: Elsevier Butterworth Heinemann; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gobel H, Heinze A, Heinze-Kuhn K. Phenotypes of chronic tension type headache. In: Olesen J, editor. Classification and diagnosis of headache disorders. New Delhi: Oxford University Press; 2006. pp. 142–5. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Unalp A, Dirik E, Kurul S. Prevalence and clinical findings of migraine and tension-type headache in adolescents. Pediatr Int. 2007;49:943–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-200X.2007.02484.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mongini F, Deregibus A, Raviola F, Mongini T. Confirmation of the distinction between chronic migraine and chronic tension-type headache by the McGill Pain Questionnaire. Headache. 2003;43:867–77. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-4610.2003.03165.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zivadinov R, Willheim K, Sepic-Grahovac D, Jurjevic A, Bucuk M, Brnabic-Razmilic O, et al. Migraine and tension-type headache in Croatia: A population-based survey of precipitating factors. Cephalalgia. 2003;23:336–43. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-2982.2003.00544.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Porta-Etessam J, Casanova I, García-Cobos R, Lapeña T, Fernández MJ, García-Ramos R, et al. Osmophobia analysis in primary headache. Neurologia. 2009;24:315–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sacco S. Diagnostic issues in tension type headache. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2008;12:437–41. doi: 10.1007/s11916-008-0074-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mongini F. Headache and Facial Pain. Stuttgart: Thieme; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lipton RB, Bigal ME. The classification of migraine. In: Olesen J, editor. Classification and diagnosis of headache disorders. New Delhi: Oxford University Press; 2006. pp. 53–61. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chakravarty A. Chronic daily headache: Clinical profile of Indian patients. Cephalalgia. 2003;23:348–53. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-2982.2003.00514.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Katsarava Z, Schneeweiss S, Kurth T, Kroener U, Fritsche G, Eikermann A, et al. Incidence and predictors for chronicity of headache in patients with episodic migraine. Neurology. 2004;62:788–90. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000113747.18760.d2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spierings EL, Ranke AH, Honkoop PC. Precipitating and aggravating factors of migraine versus tension-type headache. Headache. 2001;41:554–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-4610.2001.041006554.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Donias SH, Peioglou-Harmoussi S, Georgiadis G, Manos N. Differential emotional precipitation of migraine and tension-type headache attacks. Cephalalgia. 1991;11:47–52. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-2982.1991.1101047.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Young WB, Peres MF, Rozen TD. Modular Headache Theory. Cephalalgia. 2001;21:842–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-2982.2001.218254.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Torelli P, Beghi E, Manzoni GC. Application of diagnostic criteria for migraine without aura. In: Olesen J, editor. Classification and diagnosis of headache disorders. New Delhi: Oxford University Press; 2006. pp. 76–9. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shechter A, Stewart WF, Silberstein SD, Lipton RB. Migraine and autonomic nervous system function: A population based, case-control study. Neurology. 2002;58:422–7. doi: 10.1212/wnl.58.3.422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cortelli P, Pierangeli G, Parchi P, Contin M, Baruzzi A, Lugaresi E. Autonomic nervous system function in migraine without aura. Headache. 1991;31:457–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.1991.hed3107457.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bag B, Karabulut N. Pain relieving factors in migraine and tension type headache. Int J Clin Pract. 2005;59:760–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1368-5031.2005.00535.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gupta R, Bhatia MS. A report of cranial autonomic symptoms in migraineurs. Cephalalgia. 2007;27:22–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2006.01237.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kaup AO, Mathew NT, Levyman C, Kailasam J, Meadors LA, Villarreal SS. ‘side locked’ migraine and trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias: Evidence for clinical overlap. Cephalalgia. 2003;23:43–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-2982.2003.00451.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Al-Din AS, Mir R, Davey R, Lily O, Ghaus N. Trigeminal cephalalgias and facial pain syndromes associated with autonomic dysfunction. Cephalalgia. 2005;25:605–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2005.00935.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barbanti P, Fabbrini G, Pesare M, Vanacore N, Cerbo R. Unilateral cranial autonomic symptoms in migraine. Cephalalgia. 2002;22:256–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-2982.2002.00358.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bhatia MS, Chhabra V, Dahiya D, Dua RS, Gupta R, Sapra R, et al. A study of cranial autonomic symptoms in primary headaches. Cephalalgia. 2007;27:575–9. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Martin PR, Soon K. The relationship between perceived stress, social support and chronic headaches. Headache. 1993;33:307–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.1993.hed3306307.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rollnik JD, Karst M, Fink M, Dengler R. Botulinum toxin type A and EMG: a key to the understanding of chronic tension-type headaches? Headache. 2001;41:985–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-4610.2001.01193.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Holstege G. The emotional motor system. Eur J Morph. 1992;30:67–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bendtsen L. Central sensitization in tension-type headache – possible pathophysiological mechanisms. Cephalalgia. 2000;20:486–508. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-2982.2000.00070.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Burstein R. Deconstructing migraine headache into peripheral and central sensitization. Pain. 2001;89:107–10. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(00)00478-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Leistad RB, Sand T, Westgaard RH, Nilsen KB, Stovner LJ. Stress-induced pain and muscle activity in patients with migraine and tension-type headache. Cephalalgia. 2006;26:64–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2005.00997.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]