Abstract

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is prescribed for schizophrenia patients for various indications, in our country. However, official guidelines in other countries have been cautious in prescribing ECT for schizophrenia. To study the indications for which patients with schizophrenia receive ECT. We studied records of schizophrenia inpatients receiving ECT in one year (2005) (n=101) retrospectively, as well as the consecutive data of patients between May 2007 and June 2008 (n=101) prospectively. The various indications for ECT in schizophrenia were studied by frequency analysis. Of the 202 schizophrenia patients who received ECT, the most common reason was ‘to augment pharmacotherapy’ in (n=116) cases. The target symptoms for which ECT was prescribed the most was catatonia (n=72). The mean number of ECTs (SD) received was 8.4 (2.8). Augmentation of pharmacotherapy was the most common indication of ECT in patients with schizophrenia.

Keywords: ECT, indications, schizophrenia

INTRODUCTION

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) was first introduced as a treatment for schizophrenia in 1938, by Ugo Cerletti and Lucio Bini.[1] Later, advent of antipsychotic medications markedly reduced the use of ECT. However, in certain situations, for example, treatment-resistant schizophrenia, ECT augmentation is still the treatment of choice.[2] ECT is often used in addition to antipsychotics in the treatment of schizophrenia. Studies have shown that a combination of ECT and antipsychotics has a significant advantage with respect to rapidity or quality of response.[3–7] Treatment guidelines from the West[8,9] suggest that ECT can be used in schizophrenia for catatonia, past history of good response to ECT, and in treatment resistance. A survey of referrals to ECT in Hungary reports that treatment resistance is the most common indication, followed by catatonic symptoms, and a past history of good response to ECT.[10] A recent Cochrane review reports that ECT can be considered for patients when rapid improvement is desired and when there is a history of poor response to medication alone.[11]

Available literature is not consistent with regard to the indications of ECT in schizophrenia. This issue is particularly relevant to our country, as patients with schizophrenia are more commonly prescribed ECT. A survey of the practice of ECT in teaching hospitals in India, as well as in Asia, reports that schizophrenia (36.5% and 41.8% subsequently) is the most common diagnosis for which patients receive ECT.[10,11] Therefore, the lingering questions remain as to why schizophrenia patients receive ECT in our country? We have made an attempt to study this in an academic Psychiatric setting in India.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We reviewed the hospital records of all inpatients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia (ICD-10: F 20.0 to F 20.9) who received ECT through the year 2005 (n=101) retrospectively and from May 2007 to June 2008 (n=101) prospectively, at the National Institute of Mental Health and Neuro Sciences (NIMHANS), Bangalore, India. The ECT records at NIMHANS have been designed to incorporate all the relevant sociodemographic-, clinical-, and ECT-related information. The standard practice at the Institute is to evaluate all patients prescribed ECT with detailed psychiatric and medical history, clinical mental status, and neurological examination, complete blood picture, metabolic workup, and an electrocardiogram. Written informed consent is obtained from either the patients or from their relatives. The ECT procedure is conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

The indications for ECT were noted from the ECT record, which had the following options: (1) Adequate dosage and duration of the drug therapy that failed; (2) urgency of treatment, that is, could not afford to wait for the drug effects; (3) Drug compliance / administration was a problem; (4) drug intolerance – actual / anticipated; (5) ECT was effective earlier; (6) ECT was chosen as the first line of treatment; (7) ECT was needed to augment drug therapy; (8) Other reasons to be specified. We also studied target symptoms for which ECT was prescribed. These included (1) suicidality; (2) aggression; (3) catatonic symptoms. The outcome of ECT was assessed by a visual analog scale (1-5) administered by the primary investigator, after reviewing notes of the consultant psychiatrist and taking into consideration his opinion about the overall improvement at the end of the course of ECTs. Adequate improvement was defined as a score of three or more; while inadequate improvement was a score of two or less than two. All patients received ECT according to the standard operating procedure in the Institute, details of which have been described elsewhere.[12]

Descriptive statistics were used to characterize the demographic and clinical data of the study samples. Frequency analysis was used to study the indications of ECT and the specific symptoms that warranted ECT.

RESULTS

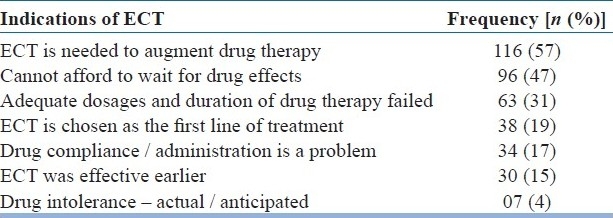

The mean (SD) age of our sample was 28.6 (8.3) years, with the number of females being 93 (46%). The mean (SD) duration of illness was 56.4 (60.7) months. The mean (SD) number of ECTs received were 8.4 (2.8) with a range of 4-6. All the patients had one or more indications. Table 1 depicts various indications of ECTs in patients with schizophrenia. Catatonia (n=72) was the most common symptom that warranted ECTs in schizophrenia patients. Aggression (n=54) and suicide (n=28) were the other reasons.

Table 1.

Various indications of ECT

Most of the patients (93%) showed adequate improvement after the course of ECTs as rated by the visual analog scale. None of the patients had ECT-related complications that warranted its discontinuation.

DISCUSSION

In this study, the most common indications for ECT in schizophrenia patients were augmentation of pharmacotherapy, followed by urgency of therapeutic response, and treatment resistance. The most common symptoms that warranted ECT were catatonia followed by aggression. ECTs were stopped because of adequate improvement in almost all the patients. The findings of our study were consistent with the findings of the Cochrane review, probably indicating that the prescription of ECT in our country does not differ much from elsewhere. Our findings also mirror the results of the Hungarian study, thereby emphasizing this point.[13,14]

This study also specifically looks into target symptoms that warranted the use of ECT in the management of schizophrenia, for example, catatonia, aggression, and suicide. Catatonia outnumbers aggression and suicide. Catatonic schizophrenia responds faster to ECT than non-catatonic schizophrenia,[15] therefore, the number of patients prescribed ECT for this indication is understandable and is uniform across all studies and guidelines.

One difference between our study and the available literature was that ECT was prescribed for patients where drug compliance could have been an issue (n=34). It may be pointed out that in these patients, ECT was probably administered because immediate clinical improvement was desired and maintenance treatment would still have involved pharmacotherapy. However, it is interesting to note that even today the indications for ECT in schizophrenia is, at times, a fall back on the time of Cerletti and Bini!

This study has the merit of looking into various indications for ECT in schizophrenia patients, both in a retrospective and prospective manner. The limitations of this study were that we used the visual analog scale to rate the overall improvement of each patient at the termination of the ECTs. We did not study the outcome of schizophrenia following ECT in a systematic manner, but only the response to ECT treatment. The cognitive side effects were also not studied. We did not include patients from other centers, thereby limiting the generalizability.

What is heartening to note is that the results of our study mirror many studies, from across countries and cultures, in the reasons for prescribing ECT in schizophrenia. However, we may need to incorporate the differences in clinical practice across countries, into the existing guidelines, in order to make them more comprehensive. This would ensure that the indications for ECT in schizophrenia would not remain as lingering questions anymore.

CONCLUSION

In our study, the most common indication for ECT in schizophrenia was to augment the effect of antipsychotics and the most common target symptom was catatonia. These findings were consistent with the findings from Western Literature.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cerletti U. Old and new information about electroshock. Am J Psychiatry. 1950;107:87–94. doi: 10.1176/ajp.107.2.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fink M, Sackeim HA. Convulsive therapy in schizophrenia? Schizophr Bull. 1996;22:27–39. doi: 10.1093/schbul/22.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taylor P, Fleming JJ. ECT for schizophrenia. Lancet. 1980;1:1380–2. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(80)92653-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ungvari GS, Petho B. High dose haloperidol therapy: Its effectiveness and a comparison with Electroconvulsive therapy. J Psy Treat Eval. 1982;4:279–83. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abraham KR, Kulhara P. The efficacy of electroconvulsive therapy in the treatment of schizophrenia.A comparative study. Br J Psychiatry. 1987;151:152–5. doi: 10.1192/bjp.151.2.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Janakiramaiah N, Channabasavanna SM, Murthy NS. ECT/chlorpromazine combination versus chlorpromazine alone in acutely schizophrenic patients. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1982;66:464–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1982.tb04504.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sarita EP, Janakiramaiah N, Gangadhar BN. Efficacy of combined ECT after two weeks of neuroleptics in schizophrenia: A doublé blind controlled study. NIMHANS J. 1998;16:243–51. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weiner RD, Coffey CE, Fochtmann LJ, Greenberg RM, Isenberg KE, Kellner CH, et al. The practice of Electroconvulsive Therapy: Recommendations for treatment, training, and privileging: A Task Force Report of the American Psychiatric Association. 2nd ed. Washington D.C.: American Psychiatric Association Inc; 2001. Indications for te use of electroconvulsive therapy; pp. 24–5. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fear CF. The use of ECT in the treatment of schizophrenia and catatonia. In: Scott AIF, editor. The ECT Handbook: The third report of the Royal College of Psychiatrist's special committee on ECT. 2nd ed. London: The Royal College of Psychiatrists Inc; 2005. pp. 40–3. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gazdag G, Sebestyen G, Zsargo E, Tolna J, Ungvari GS. Survey of referrals to electroconvulsive therapy in Hungary. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2008;25:1–5. doi: 10.1080/15622970802256180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tharyan P, Adams CE. Electroconvulsive therapy for schizophrenia.The Cochrane database of Systematic Reviews. 2005;(2) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000076.pub2. Art No: CD000076.pub2 DOI: 01002/14651858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chanpattana W, Kunigiri G, Kramer BA, Gangadhar BN. Survey of the practice of electroconvulsive therapy in teaching hospitals in India. J ECT. 2005;21:100–4. doi: 10.1097/01.yct.0000166634.73555.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chanpattana W, Kramer BA, Kunigiri G, Gangadhar BN, Kitphati R, Andrade C. A survey of the practice of electroconvulsive therapy in Asia. J ECT. 2010;26:5–10. doi: 10.1097/YCT.0b013e3181a74368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abrams R, Taylor MA. Anterior bifrontal ECT: A clinical trial. Br J Psychiatry. 1973;122:587–90. doi: 10.1192/bjp.122.5.587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thirthalli J, Phutane VH, Muralidharan K, Kumar CN, Munishwar B, Baspure P, et al. Does catatonic schizophrenia improve faster with electroconvulsive therapy than other subtypes of schizophrenia? World J Biol Psychiatry. 2009;18:1–6. doi: 10.1080/15622970902718782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]