Abstract

Deregulation of insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor (IGF-1R) and focal adhesion kinase (FAK) signaling pathways plays an important role in cancer cell proliferation and metastasis. In pancreatic cancer cells, the crosstalk and compensatory mechanisms between these two pathways reduce the efficacy of the treatments that target only one of the pathways. Ablation of IGF-1R signaling by siRNA showed minimal effects on the survival and growth of pancreatic cancer cells. An increased activity of FAK pathway was seen in these cells after IGF-1R knockdown. Further inhibition of FAK pathway using Y15 significantly decreased cell survival, adhesion, and promoted apoptosis. The combination of Y15 treatment and IGF-1R knockdown also showed significant antitumor effect in vivo. The current study demonstrates the importance of dual inhibition of both these signaling pathways as a novel strategy to decrease both in vitro and in vivo growth of human pancreatic cancer.

Keywords: FAK, IGF-1R, pancreatic cancer

INTRODUCTION

Pancreatic cancer ranks 13th in incidence but 8th as a cause of cancer death worldwide. In the United States and Europe, pancreatic cancer is the fourth leading cause of cancer death in both men and women. Chemotherapy and radiation therapy have had little impact on survival, prompting the National Cancer Institute to declare that survival for pancreatic cancer has remained unchanged for three decades, and its treatment has consistently been identified as an area of unmet medical need [1].

Focal adhesion kinase (FAK) is a protein tyrosine kinase that, as its name suggests, is localized to focal adhesions, which are contact points between a cell and its extracellular matrix. Tyrosine phosphorylation of FAK occurs in response to clustering of integrins [2], during formation of focal adhesions and cell spreading [3–5], and upon adhesion to fibronectin [6]. FAK appears to have many functions in cells, linking integrin signaling to downstream targets [7,8], acting as part of a survival signal pathway [9,10], and having a connection with cell motility [11,12]. Of particular importance to our studies is that FAK is phosphorylated following activation of a number of transmembrane receptors including insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor (IGF-1R) [13].

Several members in the IGF family signaling pathway including IGF-1, IGF-1R, IGF-2R, and IRS-1 are overexpressed in pancreatic cancer [14–17]. Several studies support the significance of the IGF-1 receptor-mediated mitogenic signal in pancreatic cancer. Both IGF-1 receptor antisense oligonucleotides and anti-IGF-1R antibodies have been shown to inhibit the proliferation of human pancreatic cancer cells. Overexpression of IRS-1 in pancreatic cancer contributes to increased activation of the IGF-1R signaling pathway [15,16].

IGF-1R and FAK signal to redundant pathways. It has been shown that FAK activates proliferation and inhibits apoptosis through PKC and PI3K-Akt pathway, which results in induction of cyclin D3 expression and CDK activity [18]. Therefore, activation of either FAK or IGF-1R induces the PI3K-Akt pathway and cell survival. Clearly, there is crosstalk and redundancy in the signaling via these tyrosine kinases, but the pathways diverge as well. Induction of the IGF-1R results in MAPK pathway activation which is independent of FAK phosphorylation and activation [19]. Recently, it has been shown that a member of the MAPK pathway (MEK kinase 1) binds to FAK, linking FAK to possible activation of this pathway [20]. It has been shown that FAK is activated by IGF-1R [13], and that IRS-1 is a substrate for FAK [21] and that FAK activity regulates IRS-1 mRNA levels [21]. Furthermore, it has been shown that FAK participates in integrin-mediated phosphorylation of the insulin receptor [22]. However, IGF-1R activity is not required for the phosphorylation of FAK, and FAK activity is not required for the phosphorylation of the IGF-1R. Due to this overlap and divergence in signaling from these tyrosine kinases, inhibition of either pathway alone may not be as efficacious as dual inhibition of both FAK and IGF-1R.

We have previously demonstrated by coimmunoprecipitation and confocal studies that FAK and IGF-1R physically interact in human pancreatic cancer cells and that these cells have survival signals operative through FAK and IGF-IR activities [23]. In this current study, we demonstrate the importance of dual inhibition of both these kinases as a novel strategy to decrease both in vitro and in vivo growth of human pancreatic cancer.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents and Antibodies

1,2,4,5-Benzenetetraamine tetrahydrochloride (Y15) was purchased from Sigma–Aldrich, St. Louis, MO. This small molecule compound has previously been shown to be a potent and specific inhibitor of FAK activity by targeting the main autophosphorylation site at Y397 [24,25]. TAE226, a dual FAK and IGF-1R kinase inhibitor, was provided by Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corp. (Basel, Switzerland). This drug has been previously shown to inhibit cancer cell growth in vitro and in vivo [23,26,27]. Anti-FAK polyclonal (c20) antibody and anti-IGF-1Rb (c20) antibody were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA); antiphospho-tyrosine monoclonal (4G10) antibody was from Upstate Biotechnology (Lake Placid, NY); antiphospho-FAK (Tyr397) was from Millipore (Billerica, MA); anti-phospho-AKT, anti-AKT, antiphospho-ERK1/2 (Thr202/Tyr204), and anti-ERK1/2 was from Cell Signaling (Beverly, MA); anti-PARP was from BD Bioscience (San Jose, CA, Catalog no. 611038), anti-β-actin antibody was from Sigma (St. Louis, MO).

Cell Culture

Panc-1 and Miapaca-2 cells were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, MD). The cells were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1 µg/mL penicillin/streptomycin.

Stable Knockdown of IGF-1R in Panc-1 Cells

A lentiviral-delivery system (a gift from Dr. Peter Chumakov at Lerner Research Institute, CCF, Cleveland) was used to introduce the siRNA expression cassette into Panc-1 and Miapaca-2 cells. In brief, DNA oligo pairs for transcription of IGF-1R-gene-specific hairpin RNA were annealed and cloned into BamHI/EcoRI site of pLSL-GFP vector to obtain the pLSL-siRNA-GFP vector. The sequences of the oligo pairs are: 5′-GAT CCG CCG ATG TGT GAG AAG ACC TTC TTC CTG TCA AAG GTC TTC TCA CAC ATC GGC TTT TTG-3′ and 5′-AAT TCA AAA AGC CGA TGT GTG AGA AGA CCT TTG ACA GGA AGA AGG TCT TCT CAC ACA TCG GCG (for si2), 5′-GAT CCC AAC GAA GCT TCT GTG ATG TTC TTC CTG TCA AAC ATC ACA GAA GCT TCG TTG TTT TTG-3′ and 5′-AAT TCA AAA ACA ACG AAG CTT CTG TGA TGT TTG ACA GGA AGA ACA TCA CAG AAG CTT CGT TGG-3′ (for si5). An oligo pair unrelated to any gene was used to produce control siRNA construct.

The pLSL-siRNA-GFP vectors were cotransfected with lentiviral packaging plasmids pCMV-VSV-G and pCMV-deltaR8.2 into 293T cells using Calphos mammalian transfection kit (Clontech Laboratories, Inc., Mountain View, CA). The media containing virus were collected 36, 40, 44, and 48 h posttransfection. After each collection, media were filtered through 0.45 µM syringe filter and were used to infect pancreatic cancer cells growing in six-well plate. Forty-eight hours after the last infection, the pancreatic cancer cells were collected and sorted for GFP expression by flow cytometry. Pancreatic cancer cells with strong GFP expression were expanded and used for all subsequent experiments. Cell lines expressing si2 and si5 are designated as Panc si2-IGF-1R and Panc si5-IGF-1R, respectively. The cell line expressing si2 is designated as Miapaca si2-IGF-1R. The control cell lines that express the control siRNA are named Panc si-ctrl or Miapaca si-ctrl. Specificity of the siRNAs for IGF-1R knockdown was confirmed with TaqMan low-density arrays (TLDAs).

Gene Expression Analysis by TaqMan Low-Density Array

TLDA preloaded with probe and primer sets specific for survival- or adhesion-related genes was purchased from Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA). Total RNA was isolated from siRNA cell lines using RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen, Catalog no. 74104). Quantitative PCR was performed by Interdisciplinary Center for Biotechnology Research at University of Florida.

Cell Viability Assay by Trypan Blue Exclusion

After Y15 treatment, cells were collected by trypsinization, washed with PBS once, and then resuspended in PBS. A fraction of the cell suspension was mixed with an equal volume of 0.4% trypan blue solution (Sigma, Catalog no. T8154) and incubated at room temperature for 5 min. Nonblue cells and blue cells were counted under microscope. Cell viability (%) was calculated as the number of nonblue cells/(number of nonblue cells + number of blue cells). LD50 was calculated using Microsoft Excel.

Apoptosis Assay by Annexin V Staining and Hoechst Staining

Early apoptosis was detected in cells 24 h after Y15 treatment using Annexin V-PE apoptosis detection kit (BD Biosciences, Catalog no. 559763).

Late apoptosis was detected in cells 72 h after Y15 treatment. Cells were collected and fixed in 3.7% formaldehyde for 10 min at room temperature. Fixed cells were washed with PBS and incubated with Hoechst 33342 (Molecular Probes/BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, Catalog no. H3570; 1:1000 dilution in PBS) for 10 min at room temperature. After washing with PBS, cells were resuspended in 80% ethanol and smeared onto a glass slide. A coverslip was mounted using 50% glycerol on the air-dried cell smear, and the slide was viewed under a fluorescent microscope for apoptotic cells showing chromatin clumping in the nucleus.

Adhesion Assay

Ninety-six-well plates coated with collagen (5 µg/mL in PBS) were washed with washing buffer (0.1% BSA in PBS) and blocked with blocking buffer (0.5% BSA in PBS). Panc-1 siRNA cell lines were treated with Y15 overnight and trypsinized. 2 × 104 cells were plated in each well and incubated at 37°C, 5% CO2 for 1 h. Plate was shaken at 2000 rpm for 15 s. Cells in each well were washed with washing buffer three times and were fixed with 3.7% paraformaldehyde for 10 min at room temperature. After being washed three times, cells were stained with crystal violet for 10 min. Subsequently, 200 µL of 2% SDS in PBS was added to each well and incubated for 30 min at room temperature. The plate was read at a wavelength of 550 µm using a microplate reader.

Immunoprecipitation and Western Blot

Cells were lysed in NP40 lysis buffer (20mM Tris–Cl, pH 7.4, 137mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 1% NP40, 2 mM EDTA, 1mg/mL of PMSF, 0.1 M Na3 VO4, 50 mM NaF, 3 µg/mL of aprotinin). Five hundred micrograms of total cell lysate was precleaned by incubating with Protein A/G agarose beads for 30 min at 4°C. The precleaned cell lysate was then incubated with 1 µg of mouse monoclonal anti-IGF-1R antibody (Calbiochem, SanDiego, CA, Catalog no. GR11) overnight at 4°C on a rotator. Twenty-five microliters of protein A/G agarose beads (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Catalog no. sc-2003) was then added to bind the antibody for another 2 h at 4°C. Samples were centrifuged at 2000g for 5 min. The precipitates were washed three times with NP40 lysis buffer and resuspended in Laemmli buffer for Western blotting analysis.

For Western blot, samples (products of immunoprecipitation or cell lysates) were mixed with Laemmli buffer and were boiled for 5 min followed by SDS–PAGE and transferred to PVDF membrane. Membranes were blocked with 5% BSA in TBST and incubated with primary antibodies according to the protocol supplied with each antibody. After washed in 0.1% TBST, the membranes were incubated with proper HRP-conjugated secondary antibody, and the immunoblots were developed with the Western Lightning™ Chemiluminescence Reagent Plus (PerkinElmer Life Sciences, Inc., Waltham, MA).

Immunohistochemistry for FAK and IGF-1R Expression

Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded normal pancreas, pancreatic cancer, and metastatic cancer specimens were obtained from the University of Florida Tumor Bank. The specimens were obtained from surgical resection or biopsy specimens obtained in the operating room at Shands Hospital in patients undergoing surgical exploration for their pancreatic cancer. Metastatic pancreatic cancer specimens were obtained from deposits in the liver or peritoneal implants of disease. Confirmation of disease was performed by pathology review by one of the authors (N.A.M.). Slides were deparaffinized and rehydrated with xylene and decreasing ethanol concentrations (100%, 95%, and 70%). Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked with 3% hydrogen peroxide in methanol. Slides were then rinsed with 1× TBS (Biocare Medical, Concord, CA). During the heat-induced antigen retrieval, sections were treated differently for FAK and the IGF-1R staining. For FAK staining, the sections were heated with a steamer while submerged in Citra buffer (Biogenex, San Ramon, CA), pH 6.0, for 30 min; for IGF-1R staining, the slides were submerged in Trilogy (Cell Marque, Rocklin, CA) which was placed in a 95°C water bath for 25 min. Sections were subsequently rinsed with 1× TBS, followed by the application of Sniper (Biocare Medical), a protein blocker, for 15 min at room temperature. Slides were then incubated overnight at 4°C with anti-FAK 4.47 mouse monoclonal antibody (1:200, Upstate Biotechnology) or anti-IGF-1R rabbit polyclonal antibody (1:400; AbCam, Cambridge, MA). Next, slides were treated with a conjugated secondary polymer, Mach 2 mouse HRP polymer (Biocare Medical) (for FAK) or rabbit HRP polymer (Biocare Medical) (for IGF-1R) for 30 min at room temperature. The chromogenic reaction was completed with Cardassian 3,3-diaminobenzidine (Biocare Medical) for 1 min at room temperature. Slides were counterstained with hematoxylin (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) for 1 min and subsequently exposed to 1× TBS for 1 min. Slides were then mounted and coverslipped with cytoseal XYL (Richard-Allen Scientific, Kalamazoo, MI).

Intensity of staining was scored by one of the authors (N.A.M.) on a scale of 0–4 with 0 = no staining, 1 = trace, 2 = mild, 3 = moderate, and 4 = strong staining.

Tumor Xenograft and Drug Treatment

Six-week-old, female nude mice were purchased from Harlan Laboratory (Indianapolis, IN). The mice were maintained in the animal facility and all experiments were performed in compliance with NIH animal-use guidelines and the treatment protocol approved by the University of Florida Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC).

5 × 106 Panc si5-IGF-1R cells were mixed with matrigel (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ) and injected subcutaneously into the flank of athymic nude mice (day 0). Animals were randomly divided into two groups on day 7. One group (n = 5) received Y15 (30 mg/kg) and the other received PBS as control treatment (n = 5). For Panc si-ctrl xenografts, 5 × 106 Panc si-ctrl cells were mixed with matrigel and injected subcutaneously into the flank of nude mice. These animals were also randomly divided into two groups on day 7, and one group (n = 5) received TAE226 (30 mg/kg), the other group received PBS (n = 5) as control treatment. The drugs and PBS were administered through intraperitoneal injection in a total volume of 0.1 mL. Tumor sizes were measured every 3 or 4 d in length (mm) × width (mm) starting from day 10. Tumor volume was calculated as volume (cm3) = ½ × length (cm) × width (cm)2.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed by t-test or Chi-square for two independent samples. For multiple group comparisons, ANOVA was utilized.

RESULTS

IGF-1R and FAK Upregulation in Primary and Metastatic Pancreatic Cancer

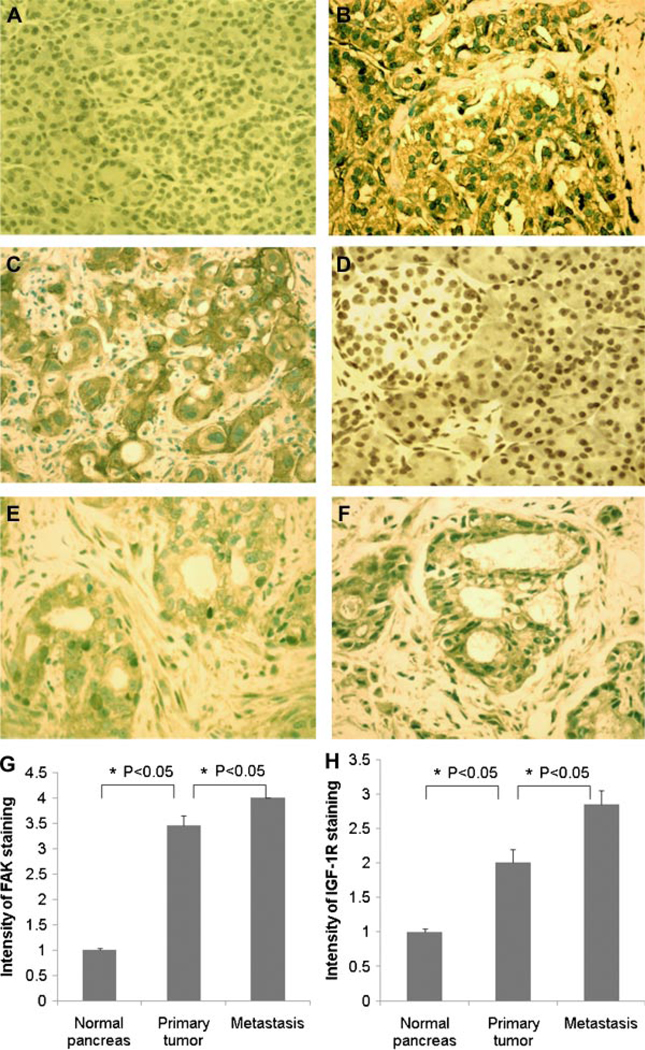

Upregulation of IGF-1R and FAK expression has been implicated in formation, progression, and metastasis of many tumors. To investigate the possible role of these pathways on pancreatic cancer, we used immunohistochemistry to study the expression of IGF-1R and FAK in normal human pancreas, primary pancreatic adenocarcinoma, and metastatic human pancreatic adenocarcinoma patient specimens. As shown in Figure 1, the expression of IGF-1R and FAK is low in a normal human pancreas. Expression is significantly upregulated in pancreatic adenocarcinoma tissues, and the levels of IGF-1R and FAK are highest in metastatic tumor compared to primary tumor, indicating that the altered activity of both IGF-1R and FAK pathways might play an important role on the malignant phenotype of pancreatic cancer.

Figure 1.

FAK and IGF-1R expression in normal pancreas and primary and metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Immunohistochemical staining of FAK in (A) normal pancreas (n = 10), (B) primary pancreatic adenocarcinoma (n = 13), and (C) metastases (n = 16). Immunostaining of IGF-1R in (D) normal pancreas (n = 10), (E) primary pancreatic adenocarcinoma (n = 13), and (F) metastases (n = 16). FAK and IGF-1R are stained brown. Magnification: 20×. (G) Intensity of FAK staining is higher in pancreatic carcinoma than in normal pancreas, and higher in metastases than in primary tumor (mean ± SE: normal pancreas: 1.0 ± 0.04; primary tumor: 3.5 ± 0.2; metastasis: 4 ± 0, P < 0.05). (H) Intensity of IGF-1R staining is higher in pancreatic carcinoma than in normal pancreas, and higher in metastases than in primary tumor (mean ± SE: normal pancreas: 1.0 ± 0.04; primary tumor: 2 ± 0.2; metastasis: 2.8 ± 0.2, P < 0.05). Intensity of staining is scored on a scale of 1–4.. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at www.interscience.wiley.com.]

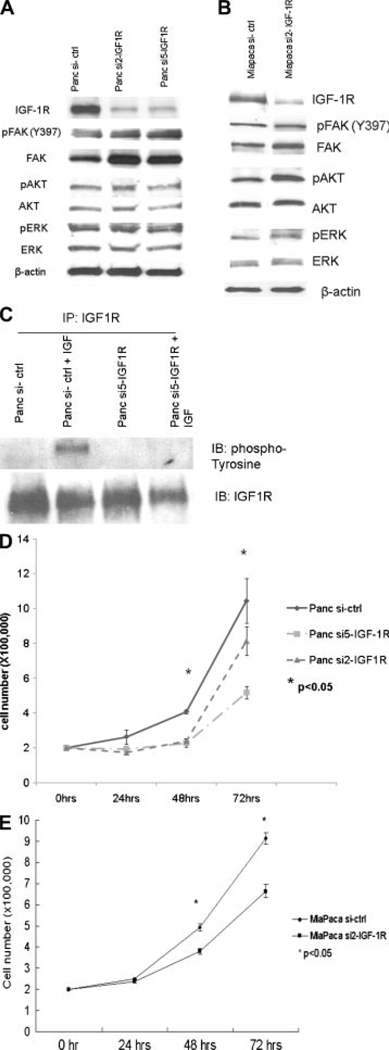

Knockdown of IGF-1R in Panc-1 Cells

Panc-1 and Miapaca-2 cells that stably express siRNA for IGF-1R show a dramatic decrease in IGF-1R level by Western blot (Figure 2A and B). Phosphorylated IGF-1R was not detectable in these cells after IGF-1 stimulation while phosphorylation of IGF-1R was seen in control cells (Figure 2C), showing that the IGF-1R signaling pathway is suppressed in the stable cell lines that express siRNA for IGF-1R. However, suppression of IGF-1R signaling in these cell lines only moderately inhibited cell growth, as shown by cell growth curves (Figure 2D and E). After 48 h of growth, numbers of IGF-1R knockdown cells were 50–78% of the number of control cells. AKT and ERK are key effecters downstream of IGF-1R, which mediate most of IGF-1R function including mitogenesis and antiapoptosis. Surprisingly, phosphorylation of AKT and ERK was not inhibited in either cell line after IGF-1R knockdown (Figure 2A and B), suggesting activation of AKT and ERK by compensatory mechanisms to provide mitogenic signals.

Figure 2.

Effect of lentiviral siRNA on IGF-1R and downstream proteins. Knockdown of IGF-1R in Panc-1 cells (A) and Miapaca-2 cells (B). Thirty micrograms of each cell lysate was used for SDS–PAGE. Decreased IGF-1R expression was seen in Panc si2-IGF-1R, Panc si5-IGF-1R, and Miapaca si2-IGF-1R cells, while increased FAK and phospho-FAK (Y397) were seen in these cells compared to cells expressing control siRNA. No significant changes in AKT, phospho-AKT, ERK, and phospho-ERK were detected in these cells. Figure representative of three replicates. (C) Lack of response to IGF-1 stimulation after IGF-1R knockdown in Panc-1 cells. Cells were treated with IGF-1 (100 ng/mL) for 30min after overnight serum starvation. Phosphorylated tyrosine residues were probed after immunoprecipitation of IGF-1R from 1mg of cell lysates. Phosphorylation of IGF-1R was seen in Panc-1 control cells after IGF-1 stimulation but not in Panc-1 si5-IGF-1R cells. Figure representative of three replicates. Panc-1 (D) and Miapaca-2 (E) cell growth is suppressed after IGF-1R knockdown. 2 × 105 cells were grown at normal condition (37°C, 5%CO2). Cell numbers were counted at 24, 48, and 72 h. The growth rate of both Panc si-IGF-1R cell lines and the Miapaca si2-IGF-1R cell line is slower than that of control cells (*P < 0.05).

Increase of FAK Signaling After Knockdown of IGF-1R

To search for the possible compensatory pathways, TLDA was used to screen for changes in expression level of various genes involved in cell adhesion. Of note, in both cell lines, FAK and Src mRNA were seen to increase after IGF-1R knockdown (Table 1). A FAK-related protein-tyrosine kinase Pyk2 was not upregulated. Western blot analysis confirmed the increase of FAK and phospho-FAK in IGF-1R knockdown cells (Figure 2A and B), suggesting that increased FAK activity might function to maintain the level of phospho-AKT and phospho-ERK, which should otherwise decrease due to loss of IGF-1R signaling. Based on these observations, it was reasonable to determine whether simultaneous inhibition of FAK signaling might synergize with IGF-1R knockdown to suppress tumor growth.

Table 1.

Change of Focal Adhesion Complex-Related Genes After IGF-1R Knockdown

| Focal adhesion complex-related proteins |

Panc si5-IGF-1R/ Panc si-ctrl |

Miapaca si2-IGF-1R/ Miapaca si-ctrl |

|---|---|---|

| FAK | 1.57 | 1.43 |

| Pyk2 | 1.04 | 0.45 |

| Paxillin | 1.1 | 0.9 |

| Src | 2 | 3.18 |

Ratio of mRNA copy (Panc si5-IGF-1R/ Panc si-ctrl and Miapaca si2-IGF-1R/Miapaca si-ctrl) was shown as determined by TLDA. Experiments were performed in duplicate.

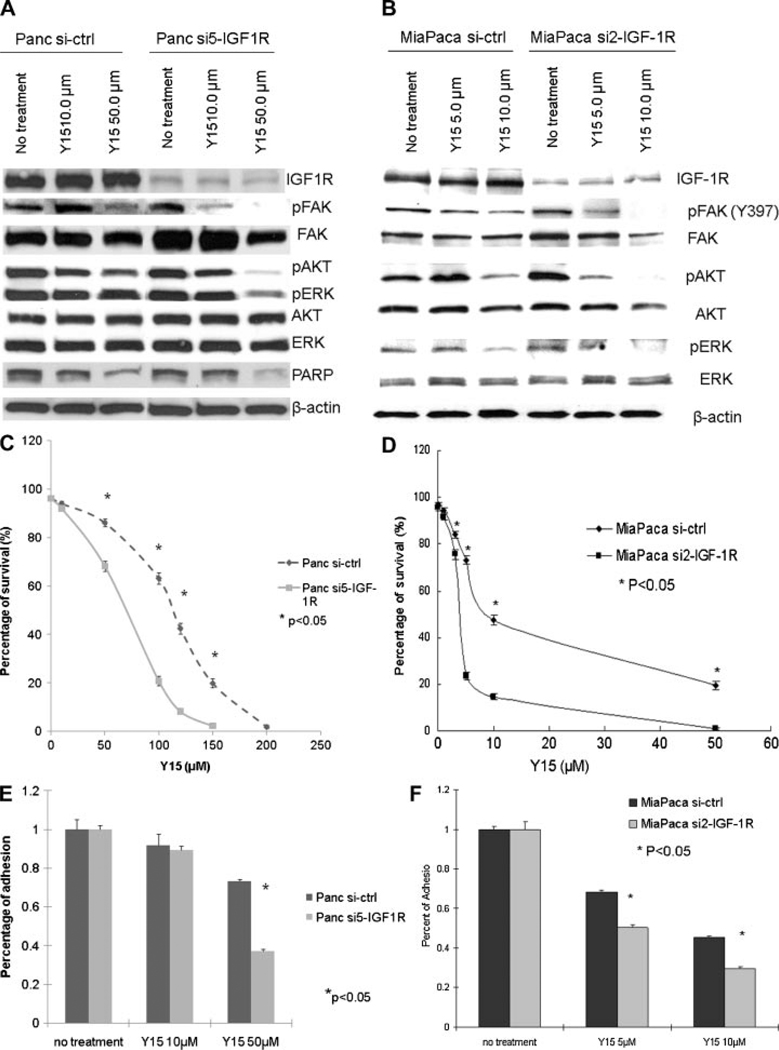

Inhibition of FAK in Pancreatic Cancer Cells Stably Expressing siRNA to IGF-1R Cells Decreases Cell Viability and Adhesion

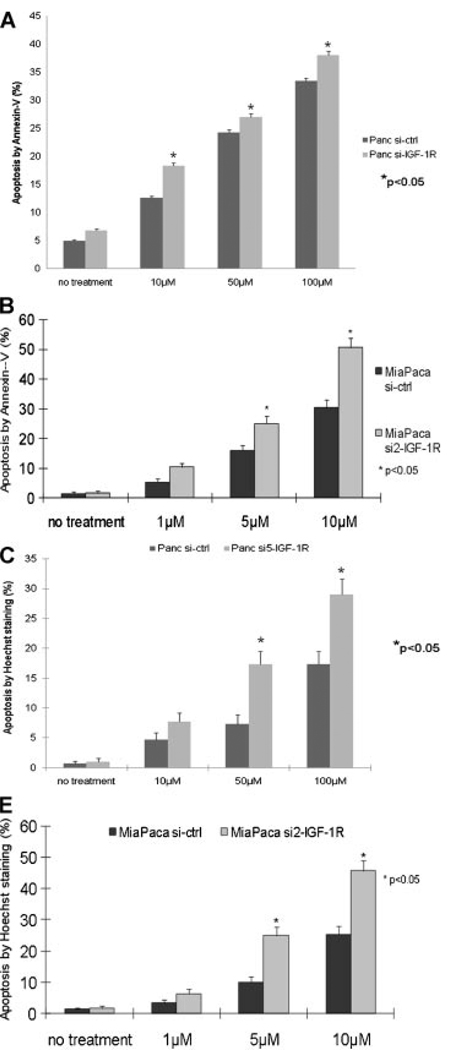

Y15 is a small molecule selected for targeting the Y397 site of FAK by structure-based in silico molecular docking. Previous studies have shown that it inhibits phosphorylation of FAK at Y397 and decreases breast and pancreatic tumorigenesis [24,25]. After Y15 treatment, Panc si5-IGF-1R and Miapaca si2-IGF-1R cells showed greater suppression of FAK phosphorylation than siRNA control cells (Figure 3A and B). Phosphorylation of AKT and ERK was also drastically suppressed in Panc si5-IGF-1R and Miapaca si2-IGF-1R cells after Y15 treatment (Figure 3A and B), implying decreased survival signaling in these cells. Indeed, Panc si5-IGF-1R cells were more sensitive to Y15 treatment than Panc si-ctrl cells, with a LD50 for Panc si5-IGF-1R cells of 69 µM versus 105 µM for Panc si-ctrl cells (Figure 3C). In addition, the LD50 for Miapaca si2-IGF-1R was 3.8 µM versus 9.0 µM for Miapaca si-ctrl (Figure 3D). Y15 treatment also significantly impaired the adhesion of Panc si5-IGF-1R and Miapaca si2-IGF-1R cells more than that of control cells (Figure 3E and F). Finally, Y15 treatment significantly induced greater apoptosis in Panc si5-IGF-1R and Miapaca si2-IGF-1R cells compared to control cells as shown by flow cytometry for Annexin V staining and Hoechst staining (Figure 4A–D). Increased apoptosis in Panc si5-IGF-1R cells was also shown in the presence of Y15 by Western blot for cleavage of PARP (Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

Effect of FAK inhibition with Y15 on IGF-1R knockdown cells. Suppression of FAK signaling in Panc-1 (A) and Miapaca-2 (B) cells after Y15 treatment. Cells were treated with different doses of Y15 for 24 h. Fifty micrograms of lysate from each treatment was separated by SDS–PAGE. Western blot showed more significant inhibition of phospho-FAK, phospho-AKT, and phospho-ERK in Panc si5-IGF-1R and Miapaca si2-IGF-1R cells than in control cells. Panc si5-IGF-1R cells also showed more PARP cleavage than Panc si-ctrl cells, indicating increased apoptosis. Figure representative of three replicates. Panc si5-IGF-1R (C) and Miapaca si2-IGF-1R (D) cells are more sensitive to Y15 treatment. Cells were treated with the indicated dose of Y15 for 24 h. Percentage of surviving cells was determined by trypan blue exclusion and plotted against Y15 doses (*P < 0.05). LD50 with Y15 for Panc si5-IGF-1R cells is lower than that for Panc si-ctrl cells (69 µM vs. 105 µM, respectively). LD50 for Miapaca si2-IGF-1R cells is 3.8 µM versus 9.0 µM for Miapaca si-ctrl. Y15 treatment decreases cell adhesion in Panc si5-IGF-1R (E) and Miapaca si2-IGF-1R (F) cells. After overnight pretreatment of Y15, cells were replated on collagen-coated surface. Percentage of adhesion was lower in Panc si5-IGF-1R and Miapaca si2-IGF-1R cells compared to control cells (*P < 0.05). Figure representative of three replicates.

Figure 4.

Y15 treatment increases apoptosis in Panc si5-IGF-1R cells. Early apoptosis after 24-h treatment with Y15. Higher percentage of apoptotic cells were detected by Annexin V staining in Panc si5-IGF-1R (A) and Miapaca si2-IGF-1R (B) cells than in control at all Y15 doses tested (*P < 0.05). Apoptosis after 72-h treatment with Y15. Following Y15 treatment, higher percentage of apoptotic cells were detected by Hoechst staining in Panc si5-IGF-1R (C) and Miapaca si2-IGF-1R (D) cells than in control cells (*P < 0.05). Figure representative of three replicates.

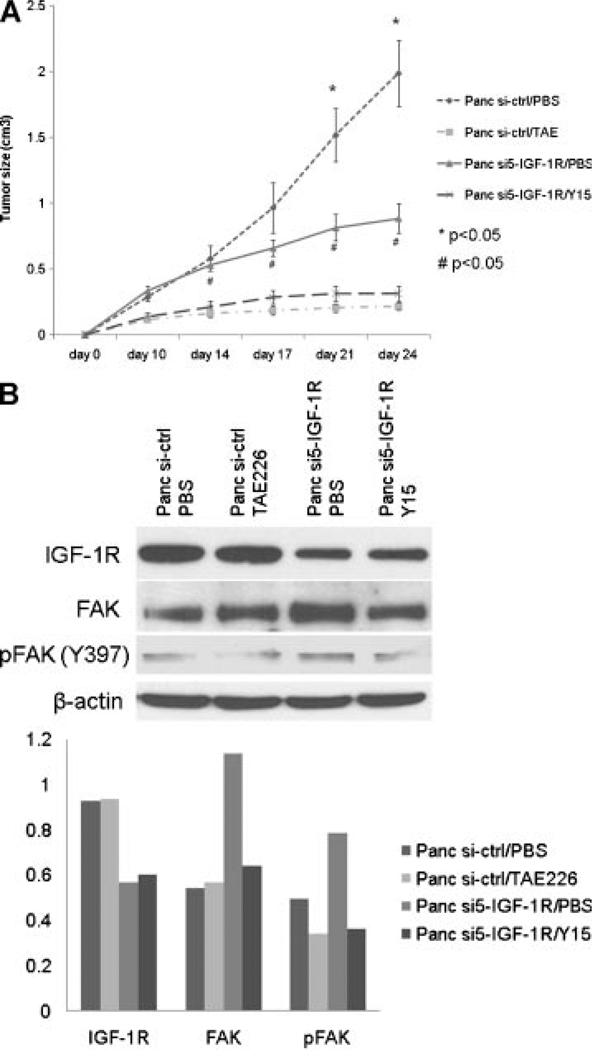

Dual Inhibition of FAK and IGF-1R Signaling Suppresses Pancreatic Cancer Cell Growth In Vivo

To further study the antitumor effect of the combination of IGF-1R knockdown and FAK inhibition, Panc si5-IGF-1R and control cells were transplanted into nude mice and tumor growth evaluated in the presence of the FAK autophosphorylation inhibitor, Y15 [24,25]. Nude mice bearing Panc si-ctrl xenografts were treated with TAE226, a dual FAK and IGF-1R tyrosine kinase inhibitor, to provide a reference for the antitumor effect of dual inhibition of FAK and IGF-1R [23,26,27]. Without drug treatment, Panc si5-IGF-1R xenografts grew slower than Panc si-ctrl xenografts (Figure 5A, Panc si5-IGF-1R/PBS vs. Panc si-ctrl/PBS), suggesting moderate tumor suppression by inhibiting the IGF-1R pathway only. Further inhibition of FAK activity by Y15 treatment suppresses the growth of Panc si5-IGF-1R xenografts more drastically (Figure 5A, Panc si5-IGF-1R/PBS vs. Panc si5-IGF-1R/Y15). A similar antitumor effect was seen in Panc si-ctrl xenografts treated with TAE226 (Figure 5A, Panc si5-IGF-1R/Y15 vs. Panc si-ctrl/TAE226). Mice demonstrated normal grooming and eating habits throughout the experiment. There was no significant weight loss with Y15 or TAE226 treatment.

Figure 5.

In vivo effects of IGF-1R knockdown and FAK inhibition. (A) Dual inhibition of FAK and IGF-1R suppresses tumor growth in nude mice. In the absence of drug treatment, at day 21 following implantation, Panc si5-IGF-1R xenografts were smaller in size than Panc si-ctrl xenografts (*P < 0.05). Y15 treatment resulted in smaller tumor sizes in Panc si5-IGF-1R transplanted mice after day 10 (Panc si5-IGF-1R/PBS vs. Panc si5-IGF-1R/Y15, #P < 0.05). No significant difference in tumor size was seen between Panc si5-IGF-1R xenografts treated with Y15 and Panc si-ctrl xenografts treated with TAE226. (B) Inhibition of phosphorylation of Y397FAK by Y15 treatment in Panc si5-IGF-1R xenografts. Equal amount of tumor lysate from individual xenografts within the same group was combined, and 50 µg of pooled lysates from each groups was analyzed by Western blot for FAK and IGF-1R expression. Knockdown of IGF-1R was confirmed in Panc si5-IGF-1R xenografts. A moderate increase in FAK and phospho-FAK was seen in xenografts from cells with IGF-1R knockdown in the absence of drug treatment (Panc si5-IGF-1R/PBS vs. Panc si-ctrl/PBS). In tumors with IGF-1R knockdown, Y15 treatment decreased phosphorylation of FAK by a similar amount as TAE226 treatment in the Panc si-ctrl xenografts. Densitometry of each band was determined using Scion image tool (Scion Corporation, Frederick, MD) and normalized with β-actin of corresponding sample.

Consistent with the in vitro observations (Figure 3A) upregulation of FAK is seen in Panc si5-IGF-1R/PBS xenografts and suppression of phosphorylation of FAK in these xenografts is achieved by Y15 treatment (Panc si5-IGF-1R/Y15, Figure 5B). These in vivo results show that the combination of IGF-1R knockdown and Y15 inhibition of FAK could be an effective therapy for human pancreatic cancer.

DISCUSSION

FAK and IGF-1R represent tyrosine kinases that have important and diverse functions in cancer cells. Previously, we have shown that FAK and IGF-1R physically interact to provide “survival signals” to protect the tumor cells from undergoing apoptosis [1]. Therefore, attenuation of FAK and IGF-1R signaling represents a novel method of gene-directed cancer therapeutics, to induce apoptosis in pancreatic cancer cells.

We have demonstrated a significant increase in FAK and IGF-1R expression in primary pancreatic cancer and their metastases. Due to redundant signaling from these kinases we expect to see little effect on adhesion, proliferation, or apoptosis when we inhibit only one pathway. As shown in Figure 2D and E, cell proliferation was decreased only moderately by stable lentiviral IGF-1R siRNA knockdown. However, there was no effect with stable lentiviral siRNA knockdown of IGF-1R on cell viability, adhesion, or apoptosis (untreated lanes in Figures Figure 33E and F and 4A–D). In addition, the effect of IGF-1R lentiviral knockdown on downstream signaling was small with no significant decrease in p-AKT (Figure 2A and B). Inhibition of IGF-1R kinase activity alone should decrease both Akt and ERK1/2 activation. However, signaling through FAK can activate Akt and possibly ERK1/2 (in the absence of IGF-1R). This is because FAK can be activated through integrin stimulation in an IGF-1R-independent manner [5]. Therefore, a compensatory increase in focal adhesion complex regulatory mRNA following lentiviral siRNA knockdown of IGF-1R may account for the minimal effects seen on cell signaling, viability, adhesion, and apoptosis following IGF-1R inhibition alone. It is possible that off target effects of the siRNA-delivery system would lead to nonspecific stimulation of gene expression [28,29]. However, TLDA failed to demonstrate off target effects from our siRNA therapy.

Dual inhibition of FAK and IGF-1R activity would be expected to inhibit cell adhesion and increase apoptosis more than inhibition of either target alone. We would expect that decreased phosphorylation of Akt would correlate with increased apoptosis. In addition, we would expect that decreased phosphorylation of ERK1/2 would correlate with decreased proliferation. Following treatment with a small molecule kinase inhibitor of FAK, cells that had siRNA knockdown of IGF-1R had a greater decrease in FAK, ERK, and Akt phosphorylation. This was associated with PARP cleavage (Figure 3A). In addition, compared to control siRNA, these cells were more sensitive to the effects of our FAK inhibitor on cell adhesion (Figure 3E and F) and apoptosis (Figure 4A–D). In addition, following FAK inhibition in cells with previous IGF-1R siRNA knockdown, there was evidence of decreased viability as demonstrated by the change inLD50 (Figure3C and D).

These in vitro findings were confirmed by our in vivo results. As shown in Figure 5A, tumor growth in vivo following lentiviral siRNA knockdown of IGF-1R was moderately slower than in the tumors derived from cells that did not have IGF-1R knockdown. However, treatment with a small molecule inhibitor of FAK autophosphorylation, Y15 [24,25], in combination with siRNA knockdown of IGF-1R decreased growth significantly compared to siRNA knockdown of IGF-1R alone, and to a similar extent to a dual FAK and IGF-1R kinase inhibitor, TAE226, obtained from Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corp. [23,26,27].

In summary, we have demonstrated that human pancreatic cancers specimens have activated FAK and IGF-1R. IGF-1R lentiviral siRNA treatment alone has minimal effect on pancreatic cancer cell proliferation, viability, adhesion, or apoptosis. However, inhibition of both FAK and IGF-1R alters downstream signaling and causes decreased adhesion and increased apoptosis compared to inhibition of FAK or IGF-1R alone.

Abbreviations

- FAK

focal adhesion kinase

- IGF-1R

insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor

- TLDA

TaqMan low-density array

REFERENCES

- 1.Hochwald SN, Cance WG, Kurenova E. Pancreatic cancer, molecular targets for therapy. In: Schwab M, editor. Encyclopedia of Cancer. 2nd edition. Springer; in press. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schaller MD, Borgman CA, Cobb BS, Vines RR, Reynolds AB, Parsons JT. pp125fak a structurally distinctive protein-tyrosine kinase associated with focal adhesions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:5192–5196. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.11.5192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kornberg LJ, Earp HS, Turner CE, Prockop C, Juliano RL. Signal transduction by integrins: Increased protein tyrosine phosphorylation caused by clustering of beta 1 integrins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:8392–8396. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.19.8392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burridge K, Turner CE, Romer LH. Tyrosine phosphorylation of paxillin and pp125FAK accompanies cell adhesion to extracellular matrix: A role in cytoskeletal assembly. J Cell Biol. 1992;119:893–903. doi: 10.1083/jcb.119.4.893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cary LA, Guan JL. Focal adhesion kinase in integrin-mediated signaling. Front Biosci. 1999;4:D102–D113. doi: 10.2741/cary. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guan JL, Shalloway D. Regulation of focal adhesion-associated protein tyrosine kinase by both cellular adhesion and oncogenic transformation. Nature. 1992;358:690–692. doi: 10.1038/358690a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schlaepfer DD, Hunter T. Integrin signaling and tyrosine phosphorylation: Just the FAKs? Trends Cell Biol. 1998;8:151–157. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(97)01172-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schlaepfer DD, Jones KC, Hunter T. Multiple Grb2-mediated integrin-stimulated signaling pathways to ERK2/mitogen-activated protein kinase: Summation of both c-Src- and focal adhesion kinase-initiated tyrosine phosphorylation events. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:2571–2585. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.5.2571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frisch SM, Vuori K, Ruoslahti E, Chan-Hui PY. Control of adhesion-dependent cell survival by focal adhesion kinase. J Cell Biol. 1996;134:793–799. doi: 10.1083/jcb.134.3.793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ilic D, Almeida EAC, Schlaepfer DD, Dazin P, Aizawa S, Damsky CH. Extracellular matrix survival signals transduced by focal adhesion kinase suppress p53-mediated apoptosis. J Cell Biol. 1998;143:547–560. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.2.547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cary LA, Chang JF, Guan JL. Stimulation of cell migration by overexpression of focal adhesion kinase and its association with Src and Fyn. J Cell Sci. 1996;109:1787–1794. doi: 10.1242/jcs.109.7.1787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ilic D, Kanazawa S, Furuta Y, Yamamoto T, Aizawa S. Impairment of mobility in endodermal cells by FAK deficiency. Exp Cell Res. 1996;222:298–303. doi: 10.1006/excr.1996.0038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baron V, Calleja V, Ferrari P, Alengrin F, Van Obberghen E. p125Fak focal adhesion kinase is a substrate for the insulin and insulin-like growth factor-I tyrosine kinase receptors. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:7162–7168. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.12.7162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stoeltzing O, Liu W, Reinmuth N, et al. Regulation of hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha, vascular endothelial growth factor, and angiogenesis by an insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor autocrine loop in human pancreatic cancer. Am J Pathol. 2003;163:1001–1011. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)63460-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bergmann U, Funatomi H, Yokoyama M, Beger HG, Korc M. Insulin-like growth factor 1 overexpression in human pancreatic cancer: Evidence for autocrine and paracrine roles. Cancer Res. 1995;55:2007–2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bergmann U, Funatomi H, Kornmann M, Beger HG, Korc M. Increased expression of insulin receptor substrate-1 in human pancreatic cancer. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;220:886–890. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.0500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ishiwata T, Bergmann U, Kornmann M, Lopez M, Beger HG, Korc M. Altered expression of insulin-like growth factor II receptor in human pancreatic cancer. Pancreas. 1997;15:367–373. doi: 10.1097/00006676-199711000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yamamoto D, Sonoda Y, Hasegawa M, Funakoshi-Tago M, Aizu-Yokota E, Kasahara T. FAK overexpression upregulates cyclin D3 and enhances cell proliferation via the PKC and PI3-kinase-Akt pathways. Cell Signal. 2003;15:575–583. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(02)00142-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arbet-Engels C, Janknecht R, Eckhart W. Role of focal adhesion kinase in MAP kinase activation by insulin-like growth factor-I or insulin. FEBS Lett. 1999;454:252–256. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)00815-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yujiri T, Nawata R, Takahashi T. MEK kinase 1 interacts with focal adhesion kinase and regulates insulin receptor substrate-1 expression. J Biol Chem. 2002;278:3846–3851. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206087200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lebrun P, Baron V, Hauck CR, Schlaepfer DD, Van Obberghen E. Cell adhesion and focal adhesion kinase regulate insulin receptor substrate-1 expression. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:38371–38377. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006162200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Annabi SE, Gautier N, Baron V. Focal adhesion kinase and src mediate integrin regulation of insulin receptor phosphorylation. FEBS Lett. 2001;507:247–252. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02981-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu W, Bloom D, Cance WG, Kurenova E, Golubovskaya V, Hochwald SN. FAK and IGF-1R interact to provide survival signals in human pancreatic adenocarcinoma cells. Carcinogenesis. 2008;29:1096–1107. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgn026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Golubovskaya VM, Nyberg C, Zheng M, et al. A small molecule inhibitor, 1,2,4,5-benzenetetraamine tetrahydrochloride, targeting the Y397 site of focal adhesion kinase decreases tumor growth. J Med Chem. 2008;51:7405–7416. doi: 10.1021/jm800483v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hochwald SN, Nyberg C, Zheng M, et al. A novel small molecule inhibitor of FAK decreases growth of human pancreatic cancer. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:2435–2443. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.15.9145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu TJ, LaFortune T, Honda T, et al. Inhibition of both focal adhesion kinase and insulin-like growth factor-I receptor kinase suppresses glioma proliferation in vitro and in vivo. Mol Cancer Ther. 2007;6:1357–1367. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shi Q, Hjelmeland AB, Keir ST, et al. A novel low-molecular weight inhibitor of focal adhesion kinase, TAE226, inhibits glioma growth. Mol Carcinog. 2007;46:488–496. doi: 10.1002/mc.20297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morris KV, Rossi JJ. Lentiviral-mediated delivery of siRNAs for antiviral therapy. Gene Ther. 2006;13:553–558. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Persengiev SP, Zhu X, Green MR. Nonspecific, concentration-dependent stimulation and repression of mammalian gene expression by small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) RNA. 2004;1:12–18. doi: 10.1261/rna5160904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]