Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) is a demyelinating disease caused by the JC virus usually in the context of immunodeficiency. We report a case of PML in a patient without evidence of immunosuppression and highlight several issues relating to diagnosis and management.

Case report.

A 62-year-old right-handed man presented with a 2-year history of progressive left-sided headache, speech difficulties, and hand clumsiness. Three weeks prior to admission he had substantial cognitive decline with concentration and memory difficulties. He reported fatigue and 15-pound weight loss. His background history included hypertension and coronary artery disease. He reported isolated, uncomplicated thoracic shingles 4 years prior. There was no history of alcohol abuse.

On examination, he was alert but disoriented to time. He had anomia with expressive aphasia. Comprehension and repetition were intact. He recalled 2 of 3 objects. Motor and sensory examinations were unremarkable. Tendon reflexes were brisk on the right. He walked unassisted but was unsteady on tandem gait.

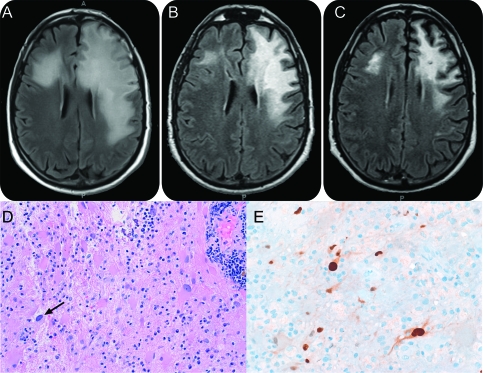

Brain MRI (figure) revealed extensive T2/fluid-attenuated inversion recovery hyperintensities involving the left frontal subcortical white matter, sparing the overlying cortex. There was vasogenic edema with ill-defined patchy contrast enhancement.

Figure. Brain MRI fluid-attenuated inversion recovery sequence and immunohistopathology of the brain tissue.

(A) At diagnosis. (B) 2 months post mefloquine. (C) 6 months post mefloquine therapy. (D) The lesion comprises perivascular and interstitial chronic inflammation, atypical astrocytes, and rare cells with viral cytopathic effect (arrow). (E) Atypical astrocytes and an inclusion-bearing cell are immunoreactive for SV40.

He proceeded to biopsy of the left frontal lesion. Histopathology (figure) showed a moderately cellular lesion with many pleomorphic astrocytes and rare cells of scant cytoplasm with nuclear homogenization consistent with viral cytopathic effect. The modest inflammatory infiltrate, atypical for classic PML, consisted of CD3+ T cells around the vessels and throughout the parenchyma, and a moderate number of largely CD20+ B cells. Immunostaining for SV40, p53, and Ki67 (Mib-1) were positive in inclusion-bearing cells and atypical astrocytes. CSF examination revealed positive JC virus DNA. A robust cellular immune response against JC virus VP1 protein, mediated by CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, were detected in his blood.

A workup for infections and malignancies was negative. His blood count and metabolic profile were normal. Autoimmune, paraprotein, paraneoplastic screen, and HIV serology were negative. His quantitative immunoglobulin assays were normal. T-cell subset analysis showed normal CD4+ T-cell count (1,204/mm3) and CD4+/CD8+ ratio. A whole body PET-CT revealed no malignancy.

The patient was enrolled in a mefloquine clinical trial (ClinicalTrial.gov identifier: NCT00746941). There was appreciable improvement with more spontaneous speech. He continued on open-label mefloquine after 6 months. Nine months after the initiation of mefloquine, there was minimal expressive aphasia only.

Discussion.

This case highlights several issues. First is the diagnosis of PML in apparently immunocompetent individuals.1 PML is typically caused by reactivation of the JC virus almost exclusively in the context of immunodeficiency, most commonly advanced HIV infection, hematologic malignancies, and more recently with immunomodulatory monoclonal antibodies. It is commonly thought that patients with PML have defective cellular immunity.2 We postulate that this patient possibly had a transient dysfunction of cellular immunity—for example, subclinical parvovirus B19 infection—sufficient to promote the reactivation of JC virus. Both quantitative and functional assay of T-cell subsets were normal in our patient. The intracellular cytokine staining assay measured the production of interferon-γ by T cells after stimulation with JC virus peptide covering the entire VP1 protein.

Second, the atypical 2-year history of progressive symptoms distinguishes this patient from the more typical presentation of PML occurring in immunodeficient patients, which usually progresses over months. This could reflect an attenuation of the evolution of the white matter lesions in this patient, perhaps because the degree of immunodeficiency was milder, or more selective. The patient had a cellular immune response against JC virus, which is usually associated with a favorable clinical outcome.3 The mortality of PML was 90% in patients with AIDS before the advent of antiretroviral therapy, with median survival averaging just 6 months.4 In a cohort of patients with PML with minimal or occult immunosuppression, which included patients with renal/liver disease and idiopathic CD4+ T-cell lymphopenia, the mortality was 71% within 1.5 to 120 months (median 8 months) from onset of symptoms.5

Third, the radiologic features suggest substantial inflammatory changes with vasogenic edema and contrast enhancement. Such radiologic features are more commonly seen in PML with immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome.6 This suggests some recovery of the postulated transient cellular immunity defect in our patient.

To date, only immune restoration with antiretroviral therapy in the setting of AIDS have been shown to improve survival. Our patient, without overt immunodeficiency, received mefloquine. Mefloquine has been shown to have high CNS penetration to achieve efficacious levels in the brain.7 The trial has been stopped; final analyses are pending.

PML can occur in apparently immunocompetent individuals. The clinical presentation may be more indolent, with inflammatory features on neuroimaging. Treatment options are limited to date.

Footnotes

Disclosure: Dr. Tan reports no disclosures. Dr. Koralnik has served on scientific advisory boards for Roche, GlaxoSmithKline, and Merck Serono; serves on the editorial board of Journal of NeuroVirology; receives publishing royalties from UpToDate, Inc.; has served as a consultant for Bristol-Myers Squibb, Ono Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., Merck Serono, Roche, GlaxoSmithKline, Alnylam Pharmaceuticals, and Antisense Therapeutics Limited, and Vertex Pharmaceuticals; and receives research support from Biogen Idec, the NIH, and the National Multiple Sclerosis Society. Dr. Rumbaugh has received research support from the NIH/NIMH. Dr. Burger and A. King-Rennie report no disclosures. Dr. McArthur serves on a scientific advisory board for CNS Bio Services; receives publishing royalties for Current Therapy in Neurologic Disease, 7th Edition (Mosby, 2006); is an author on patents re: Device for thermal stimulation of small neural fibers and Immunophilin ligand treatment of antiretroviral toxic neuropathy; receives research support from Biogen Idec, Pfizer Inc, the NIH, and the Foundation for Peripheral Neuropathy; and holds stock options in GliaMed, Inc.

Author contributions:

Ik Lin Tan: design, analysis and writing of the manuscript. Igor J. Koralnik: performed immunological analyses of the cellular response against JC virus in the patient; design, writing and review of the manuscript. Jeffrey A. Rumbaugh: design, analysis and review of manuscript. Peter Burger: neuropathology work, analysis and review of manuscript. Agnes King-Rennie: study coordination and data collection. Justin C. McArthur: design, analysis and writing of manuscript.

References

- 1. Arai Y, Tsutsui Y, Nagashima K, et al. Autopsy case of the cerebellar form of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy without immunodeficiency. Neuropathology 2002;22:48–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tan CS, Koralnik IJ. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy and other disorders caused by JC virus: clinical features and pathogenesis. Lancet Neurol 2010;9:425–437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Marzocchetti A, Tompkins T, Clifford DB, et al. Determinants of survival of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. Neurology 2009;73:1551–1558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Berger JR, Major EO. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. Semin Neurol 1999;19:193–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gheuens S, Pierone G, Peeters P, Koralnik IJ. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in individuals with minimal or occult immunosuppression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2010;81:247–254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Tan K, Roda R, Ostrow L, McArthur JC, Nath A. PML-IRIS in patients with HIV infection. Neurology 2009;72:1458–1464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Brickelmaier M, Lugovskoy A, Kartikeyan R, et al. Identification and characterization of mefloquine efficacy against JC virus in vitro. Antimicrob Chemother 2009;53:1840–1849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]