Abstract

Chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) is induced by the BCR-ABL oncogene, a product of Philadelphia (Ph) chromosome. The BCR-ABL kinase inhibitor imatinib is a standard treatment for Ph+ leukemia, and has been shown to induce a complete hematologic and cytogenetic response in most chronic phrase CML patients. However, imatinib does not cure CML, and one of the reasons is that imatinib does not kill leukemia stem cells (LSCs) in CML both in vitro and in vivo. Recently, several new targets or drugs have been reported to inhibit LSCs in cultured human CD34+ CML cells or in mouse model of BCR-ABL induced CML, including an Alox5 pathway inhibitor, Hsp90 inhibitors, omacetaxine, hedgehog inhibitor and BMS-214662. Specific targeting of LSCs but not normal stem cell is a correct strategy for developing new anti-cancer therapies in the future.

Keywords: BCR-ABL, Leukemic stem cells, CML, Therapeutic agents

Introduction

Chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) is a myeloproliferative disease characterized by massive expansion of granulocytic cells, leading to high white blood cell (WBC) counts and marked splenomegaly. A chromosomal translocation between chromosome 9 and 22[t(9;22)(q34;q11)], resulting in the formation of Philadelphia (Ph) chromosome and at the molecular level, a chimeric gene known as BCR-ABL responsible for CML initiation by causing a clonal expansion of BCR-ABL-expressing hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs). CML often initiates in a chronic phase, and without intervention, eventually progresses to a terminal blastic phase [1]. In general, based on their molecular weights, there are three types of human BCR-ABL chimeric genes: P190, P210 and P230; each form of the BCR-ABL oncogene is mainly associated with a distinct type of human leukemia. For example, P190 is always present in B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL) [2]; P210 is mainly involved in CML and some acute lymphoid and myeloid leukemias in blast crisis [2]; P230 is associated with a very mild form of CML3. BCR-ABL activates many signaling pathways, including Ras small GTPase, mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), signal transducers and activator of transcription (STAT), c-jun N-terminal kinase (JNK/SAPK), phosphoinositide 3-kinases (PI3K), nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-B) and myelocytomatosis oncogene (c-Myc), through which BCR-ABL promotes survival and proliferation and reduces apoptosis of leukemia cells [4]. BCR-ABL is a non-receptor tyrosine kinase, and it is obvious that a straightforward strategy for treating CML is to use drugs that shut down BCR-ABL kinase activity.

The BCR-ABL kinase inhibitor imatinib mesylate (Gleevec) is a standard of care for Ph+ leukemia, and has been shown to induce a complete hematologic and cytogenetic response in most chronic phase CML patients [5]. Although it is very effective in treating chronic phase CML patients, imatinib will unlikely provide a cure to these patients for two obvious reasons. One reason is that BCR-ABL develops imatinib-resistant mutations in its kinase domains. Recently, other BCR-ABL kinase inhibitors have been developed to overcome imatinib resistance, including dasatinib and nilotinib. However, these drugs are still ineffective to BCR-ABL-T315I mutant that is present in about 15–20% of imatinib-resistant patients [6]. Another reason is that leukemia stem cells in CML are insensitive to imatinib treatment [6, 7].

Leukemia Stem Cells

Stem cells have two unique functions: self-renewal that produces themselves and differentiation that gives rise to mature functional cells in variable tissues in the body [8]. Leukemia stem cells (LSCs) are defined as a small cell population required for the initiation and maintenance of leukemia [8–12]. In CML patients, bone marrow (BM) CD34+ Lin− cells, in which normal HSCs reside, are thought to contain CML stem cells and be responsible for disease initiation, progression and resistance to imatinib [6, 7]. Similarly, in mice with BCR-ABL induced CML, LSCs are phenotypically similar to normal HSCs and BCR-ABL-expressing HSCs (GFP+/Lin/c-Kit+/Sca-1+) are able to induce CML in secondary recipient mice [13]. It has been shown that human CD34+ CML stem cells cannot be effectively killed by BCR-ABL kinase inhibitor imatinib treatment both in vitro [7] and in vivo [6]. Specifically, in a cell culture assay, CD34+ CML stem cells, especially the undivided CD34+ cell population, are not sensitive to inhibition by imatinib [7]. Furthermore, BCR-ABL transcripts are still detectable in CD34+ BM cells from CML patients after a long-term treatment with imatinib [6], suggesting that these LSCs cannot be eradicated through inhibiting BCR-ABL kinase activity. Similarly, imatinib does not eradicate LSCs in CML mice, because total numbers and percentages of LSCs in BM of imatinib treated mice continued to increase during the treatment [14]. It is important to point out that the insensitivity of LSCs to imatinib is not associated with the development of imatinib-resistant mutations on BCR-ABL. Together, these results indicate that some unknown pathways contribute to the maintenance of survival and self-renewal of LSCs, and identification of novel genes that play critical role in regulating the function of LSCs will help to develop new therapeutic strategies through targeting LSCs.

Novel Therapeutic Drugs Against LSCs

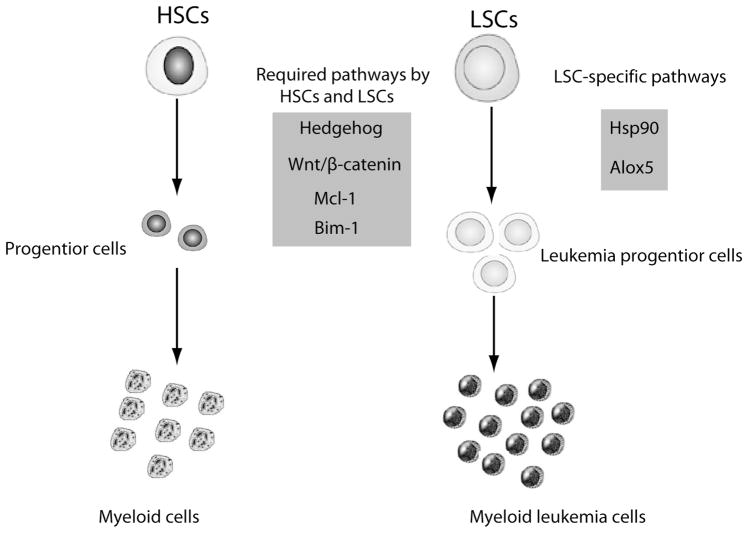

The best way to identify stem cell targets in CML is to fully understand CML-initiating genetic changes. BCR-ABL is believed to be the main genetic alteration that represents a major difference between normal HSCs and BCR-ABL-expressing LSCs, although the molecular differences between HSCs and LSCs are still unclear. We speculate that a series of aberrantly expressed genes regulated by BCR-ABL exist and collectively turn a normal HSC into a LSC, although both of them express similar phenotypic markers on cell surface. To reach a goal of curing CML, therapeutic strategies aiming to target LSCs must be developed. Towards this goal, two general strategies have been tested. One strategy is to inhibit genes that play roles in functional regulation of both normal HSCs and LSCs. The examples include hedgehog, Wnt/β-catenin and Bim-1 [15–17]. Another strategy is to inhibit genes that play crucial roles in functional regulation of LSCs but not normal HSCs. Following these two strategies, several LSC target genes and drugs have been reported (Fig. 1). Below we describe some representative anti-LSC agents and underlying mechanisms.

Fig. 1.

HSCs:Hematopoietic stem cells; LSCs: Leukemia stem cells.

Alox5 Pathway Inhibitor

The arachidonate 5-lipoxygenase (5-LO) gene (Alox5) has been shown to regulate numerous physiological and pathological progresses, including inflammation and cancer [18–20]. Alox5 is differentially expressed in CD34+ human CML cells and an in vitro study shows that an Alox5 inhibitor suppresses proliferation and induces apoptosis of K562 cells (a human CML cell line) [21–23], although an off-target effect of the Alox5 inhibitor needs to be ruled out. These data suggest a possibility that Alox5 is involved in CML development. However, it has never been thought that Alox5 may regulate the function of LSCs in CML until a recent discovery of the essential role of Alox5 in survival and self-renewal of LSCs. In this recent study, Alox5 is identified as a key gene that regulates the function of LSCs in CML mice, as BCR-ABL cannot induce CML in mice in the absence of the Alox5 gene. This striking discovery provides a unique opportunity to develop a novel anti-cancer stem cell therapy for CML [24].

Zileuton, a drug that has been currently used to treat human asthma, specifically inhibits the enzymatic activity of 5-LO, the product of the Alox5 gene [25]. To test its therapeutic effect on CML, BCR-ABL transduced BM cells were transplanted into recipient mice to induce CML, and then the CML mice were treated with a placebo, Zileuton or imatinib alone, or two agents in combination. All placebo-treated mice developed and died of CML within 4 weeks after the induction of CML by BCR-ABL, and Zileuton alone was even more effective than imatinib in prolonging survival of CML mice. About 7 weeks after the treatment with Zileuton, GFP+ Gr-1+ leukemia cells in peripheral blood of the mice gradually declined and dropped from over 50% to less than 2%, indicating that myeloid leukemia is eventually eliminated. Treatment of CML mice with both Zileuton and imatinib had a better therapeutic effect than with either Zileuton or imatinib alone in prolonging survival of the mice. At the early stage of CML development, Zileuton treatment only caused a less marked reduction of white blood cell counts than did imatinib treatment. This therapeutic effect of Zileuton on CML is caused by inhibiting LSCs. Long-term (LT)-LSCs were found to accumulate in BM of the treated mice; however, short-term (ST)-LSCs and multipotent progenitor cells (MPPs were gradually depleted, suggesting that inhibition of 5-LO by Zileuton causes the blockade of differentiation of LT-LSCs. The inhibitory effect of Zileuton are consistent with those from above-described genetic studies using Alox5−/−mice, demonstrating that targeting of the Alox5 pathway is potentially curative for CML, and this idea needs to tested in human CML patients.

Hsp90 Inhibitors

Hsp90 is a ubiquitously expressed chaperone protein which accounts for about 1–2% of total cellular protein in mammalian cells [26]. It is a chaperone of several oncoproteins such as Her2 [27], v-Src [28] and BCR-ABL [29], and plays a role in regulating survival, proliferation apoptosis of cancer cells. Hsp90 is constitutively expressed at a level that is 2–10 folds higher in tumor cells than in their normal stem cell counterparts, suggesting that Hsp90 is a potential therapeutic target in cancers. The benzoquinone ansamycin geldanamycin (GA) is the first inhibitor of Hsp90 [28] and it destructs the v-Src-Hsp90 herterprotein complex to inhibit the v-Src mediated transformation in vitro. BCR-ABL has also been shown to be a major client protein of Hsp90 in a study using human K562 CML cells [29]. In this study, after the cells were briefly exposed to GA, BCR-ABL was dissociated with Hsp90 and P23. 17-allylamino-17-demethoxygeldanamycin (17-AAG) is a less toxic analogue of GA, and it induces cytosolic accumulation of cytochrome c and cleavage of caspase-9 and caspase-3, triggering apoptosis of HL-60/BCR-ABL and K562 cells [30]. 17-AAG down-regulates intracellular BCR-ABL and c-Raf proteins, and reduces activity of Akt kinase in K562 cells [30]. Although GA or 17-AAG shows their inhibitory effect on cultured leukemia cells, their poor solubility and complex organic formulations make it likely that it is necessary to develop better Hsp90 inhibitors. Thus, a new analogue of 17-AAG, IPI-504, has been produced [31]. IPI-504 is a hydrochloride salt, and can be purified and stored at low temperatures under N2 atmosphere as a solid, resulting in a high aqueous solubility (250 mg/ml), and stability in acidic aqueous buffers (pH 3, >10 h)31]These characteristics indicate that IPI-504 is a more applicable drug for therapy.

It has been shown that IPI-504 efficiently induces dissociation of BCR-ABL and Hsp90 in BCR-ABL-expressing 32D cells as quickly as 30 min after the treatment. Because the stability of BCR-ABL is shown in vitro to be more dependent on Hsp90 when it carries imatinib-resistant mutations32] the dependence of mutant BCR-ABL on Hsp90 has been tested further in vivo. In mice with CML induced by wild type BCR-ABL or the BCR-ABL-T315I mutant, treatment with IPI-504 alone significantly prolonged the survival of mice with wild-type BCR-ABL-induced CML, but more markedly prolonged the survival of mice with BCR-ABL-T315I-induced CML [33]. The markedly prolonged survival of the IPI-504-treated mice with BCR-ABL-T315I-induced CML correlates with the more significant in vivo degradation of the mutant BCR-ABL than that of wild type BCR-ABL. In CML mice, HSCs harboring BCR-ABL (GFP+) function as LSCs [13]. Using this mouse CML stem cell model, BMells from mice with T315I-induced CML were isolated from the mice, and cultured under the conditions that support survival and growth of HSCs. During the culture, the BM cells were treated with IPI-504. Six days after the treatment, fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis shows that compared with the untreated group, imatinib treatment did not lower the percentage and the number of LSCs, whereas IPI-504 treatment had a dramatic inhibitory effect on the stem cells [33]. To assess the effect of IPI-504 on LSCs in vivo, CML mice were treated with IPI-504, and the number of LSCs in BM was analyzed 6 days after the treatment. Consistent with the in vitro data, IPI-504 treatment had a dramatic inhibitory effect on LSCs in CML mice. These studies demonstrate that inhibition of Hsp90 can effectively inhibit the survival and proliferation of LSCs. Because knocking down Hsp90a and Hsp90b are embryonic lethal, it is still not possible to genetically prove the importance of Hsp90a and Hsp90b in LSCs. However, it is a very important approach to take to investigate the role of Hsp90 in regulating the function of LSCs.

Omacetaxine

Omacetaxine (formerly homoharringtonine) is a cephalotaxine ester derived from the evergreen tree, Cephalotaxus harringtonia, native to China. Omacetaxine has shown clinical activity alone and in combination with imatinib in CML patients resistant to imatinib or other tyrosine kinase inhibitors, although it is not clear whether this drug could be effective in inhibiting LSCs for a while [34–36]. Recently, omacetaxine has been shown to have the ability to effectively kill LSCs in vitro and in vivo [37]. After treating LSCs from CML mice with omacetaxine for 6 days, LSCs (GFP+/Lin−/c-Kit+/Sca-1+) were inhibited by omacetaxine in a dose-dependent manner. The effect of omacetaxine on LSCs in CML mice was also examined. Mice with BCR-ABL-induced CML were treated with omacetaxine for 4 days from day 10 after BMT, and omacetaxine treatment resulted in a great reduction of the numbers of both LSCs and total leukemia cells. Because of its mechanism that is different from tyrosine kinase inhibitors, omacetaxien also showed an inhibitory effect on LSCs harboring BCR-ABL-T315I. This inhibitory on BCR-ABL-T315I induced CML was more effective than on wild-type BCR-ABL induced CML, which is supported by an earlier in vitro study [38]. The underlying mechanism for the inhibitory effect of omacetaxine on LSCs is still unknown, although several potential pathways are thought to be involved. The clues come from this study using omacetaxine. First, the expression of BCR-ABL is reduced by omacetaxine, likely through affecting Hsp90 that stabilizes BCR-ABL proteins. Second, an important short-lived anti-apoptotic BCL-2 family protein induced myeloid leukemia cell differentiation protein (MCL-1) is found to be down-regulated after treatment with omacetaxine. It is reasonable to think that omacetaxine could act by directly or indirectly inhibiting the BCR-ABL, MCL-1 and HSP90 in CML cells. In addition, the clinical efficacy of omacetaxine in CML could be due, at least in part, to its inhibitory activity on LSCs [37].

Hedgehog Inhibitor

Hedgehog (Hh) signaling is involved in regulation of normal development and oncogenesis of many tissue types, and has been shown to play a role in preserving and increasing the short-term repopulating capacity of human HSCs [39]. Recently, Hh signaling has been demonstrated as a required functional pathway for CML stem cells, as a loss of this pathway impairs leukemia progression [15, 40]. In these studies, Smo−/− mice (lacking the receptor for Hh) were used to induce CML. Wild-type bone marrow cells transduced with BCR–ABL caused CML in 94% of recipients within 3 months, whereas BCR-ABL transduced Smo−/− cells caused CML in only 47% of recipients. The frequency of LSCs (Lin−/c-Kit+/Sca-1+) was significantly reduced in the absence of the Hh receptor. These results suggest that CML stem cells depend on the Hh pathway for survival and self-renewal, raising a possibility that these stem cells may be targeted by pharmacological blockade of Hh signaling [40]. Because cyclopamine inhibits Hh signalling by stabilizing Smo in its inactive form, BCR-ABL induced CML mice were further treated with cyclopamine [40, 41]. The control animals died of CML within 4 weeks; however, 60% of the cyclopamine-treated mice were still alive after 7 weeks. In addition, cyclopamine-treated mice had up to a 14-fold reduction in the CML stem cell population. Targeting of CML stem cells by cyclopamine appeared to be most effective when it was used at early stages after CML induction in mice. Furthermore, cyclopamine was tested on imatinib-resistant CML in mice. BCR-ABL-T315I induced leukemia cells were unresponsive to imatinib, but their growth was reduced by 2.5-fold after treatment with cyclopamine. Cyclopamine was also effective in treating mice with BCR-ABL-T315I induced CML. Another new Hh inhibitor GDC-0449 locks onto and deactivates a protein called Smoothened, which activates the Hedgehog signaling pathway [42]. Recently, GDC-0449 was reported to reverse the medulloblastoma effectively although it has not been tested in leukemia patients [42]. These results indicate that the Hh pathway is required for the functional regulation of CML stem cells, and the use of a Hh inhibitor such as cyclopamine and GDC-0449, may be an effective strategy for treating human CML, although its effects on normal HSCs needs to be examined.

BMS-214662

BMS-214662 is a cytotoxic farnesyltransferase inhibitor and is reported to kill nonproliferating tumor cells [43]. In this study, BMS-214662, alone or in combination with imatinib or dasatinib, induces apoptosis of both proliferating and quiescent primitive CD34+CD38− CML stem cells. In contrast, normal CD34+ HSCs were much less sensitive to BMS-214662 inhibition, suggesting a selectivity of this compound for CML stem cells. The selective inhibitory effect of BMS-214662 on CML stem cells was unique to BMS-214662, as BMS-225975, a structurally similar farnesyltransferase inhibitor, did not inhibit CML stem cells, suggesting that the effect of BMS-214662 on CML stem cells is mediated through a mechanism not associated with its farnesyltransferase activity. It is likely that there are several apoptotic pathways involved, such as Bax conformational changes, loss of mitochondrial membrane potential, generation of reactive oxygen species, release of cytochrome c, and caspase-9/3 activation. These changes were coupled with up-regulation of protein kinase Cβ (PKCβ), down-regulation of E2F1 and phosphorylation of cyclin A-associated cyclin-dependent kinase 2. Co-treatment of CML CD34+ and CD34+ CD38− cells with PKC modulators, bryostatin-1 or hispidin, markedly decreased these early biochemical events and the subsequent apoptosis. These data indicate that BMS-214662 may provide a molecular framework for development of novel therapeutic strategies [44, 45].

Conclusions

These ideas discussed in this review emphasize several points. First, specific inhibition of LSCs in CML is a feasible and reasonable approach to developing a cure for CML in the future. Second, several gene products required by LSCs have been identified and shown to be good targets for inhibiting LSCs, and among them, Alox5 is particularly important because it is much more specifically required for LSCs comparing to other gene products discussed in this review. Third, several promising drugs are available for inhibiting CML stem cells in future clinical trials, inhibitors of Alox5, Hh and Hsp90 pathways have better specificity on LSCs. The mechanisms by which these pathways regulate the function of LSCs need to be further studied.

References

- 1.Bartram CR, de Klein A, Hagemeijer A, van Agthoven T, Geurts van Kessel A, Bootsma D, Grosveld G, Ferguson-Smith MA, Davies T, Stone M, et al. Translocation of c-ab1 oncogene correlates with the presence of a Philadelphia chromosome in chronic myelocytic leukaemia. Nature. 1983;306(5940):277–280. doi: 10.1038/306277a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Deininger MW, Goldman JM, Melo JV. The molecular biology of chronic myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2000;96(10):3343–3356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pane F, Frigeri F, Sindona M, Luciano L, Ferrara F, Cimino R, Meloni G, Saglio G, Salvatore F, Rotoli B. Neutrophilic-chronic myeloid leukemia: a distinct disease with a specific molecular marker (BCR/ABL with C3/A2 junction) Blood. 1996;88(7):2410–2414. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sattler M, Griffin JD. Molecular mechanisms of transformation by the BCR-ABL oncogene. Semin Hematol. 2003;40(2 Suppl 2):4–10. doi: 10.1053/shem.2003.50034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Druker BJ, Talpaz M, Resta DJ, Peng B, Buchdunger E, Ford JM, Lydon NB, Kantarjian H, Capdeville R, Ohno-Jones S, Sawyers CL. Efficacy and safety of a specific inhibitor of the BCR-ABL tyrosine kinase in chronic myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(14):1031–1037. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200104053441401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhatia R, Holtz M, Niu N, Gray R, Snyder DS, Sawyers CL, Arber DA, Slovak ML, Forman SJ. Persistence of malignant hematopoietic progenitors in chronic myelogenous leukemia patients in complete cytogenetic remission following imatinib mesylate treatment. Blood. 2003;101(12):4701–4707. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-09-2780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Graham SM, Jorgensen HG, Allan E, Pearson C, Alcorn MJ, Richmond L, Holyoake TL. Primitive, quiescent, Philadelphia-positive stem cells from patients with chronic myeloid leukemia are insensitive to STI571 in vitro. Blood. 2002;99(1):319–325. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.1.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reya T, Morrison SJ, Clarke MF, Weissman IL. Stem cells, cancer, and cancer stem cells. Nature. 2001;414(6859):105–111. doi: 10.1038/35102167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jordan CT, Guzman ML, Noble M. Cancer stem cells. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(12):1253–1261. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra061808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pardal R, Clarke MF, Morrison SJ. Applying the principles of stem-cell biology to cancer. Nat Rev. 2003;3(12):895–902. doi: 10.1038/nrc1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rossi DJ, Jamieson CH, Weissman IL. Stems cells and the pathways to aging and cancer. Cell. 2008;132(4):681–696. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang JC, Dick JE. Cancer stem cells: lessons from leukemia. Trends Cell Biol. 2005;15(9):494–501. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2005.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hu Y, Swerdlow S, Duffy TM, Weinmann R, Lee FY, Li S. Targeting multiple kinase pathways in leukemic progenitors and stem cells is essential for improved treatment of Ph+ leukemia in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(45):16870–16875. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606509103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hu Y, Chen Y, Douglas L, Li S. beta-Catenin is essential for survival of leukemic stem cells insensitive to kinase inhibition in mice with BCR-ABL-induced chronic myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 2009;23(1):109–116. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dierks C, Beigi R, Guo GR, Zirlik K, Stegert MR, Manley P, Trussell C, Schmitt-Graeff A, Landwerlin K, Veelken H, Warmuth M. Expansion of Bcr-Abl-positive leukemic stem cells is dependent on Hedgehog pathway activation. Cancer Cell. 2008;14(3):238–249. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhao C, Blum J, Chen A, Kwon HY, Jung SH, Cook JM, Lagoo A, Reya T. Loss of beta-catenin impairs the renewal of normal and CML stem cells in vivo. Cancer Cell. 2007;12(6):528–541. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lessard J, Sauvageau G. Bmi-1 determines the proliferative capacity of normal and leukaemic stem cells. Nature. 2003;423(6937):255–260. doi: 10.1038/nature01572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Catalano A, Rodilossi S, Caprari P, Coppola V, Procopio A. 5-Lipoxygenase regulates senescence-like growth arrest by promoting ROS-dependent p53 activation. EMBO J. 2005;24(1):170–179. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen XS, Sheller JR, Johnson EN, Funk CD. Role of leukotrienes revealed by targeted disruption of the 5-lipoxygenase gene. Nature. 1994;372(6502):179–182. doi: 10.1038/372179a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Radmark O, Werz O, Steinhilber D, Samuelsson B. 5-Lipoxygenase: regulation of expression and enzyme activity. Trends Biochem Sci. 2007;32(7):332–341. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2007.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Graham SM, Vass JK, Holyoake TL, Graham GJ. Transcriptional analysis of quiescent and proliferating CD34+ human hemopoietic cells from normal and chronic myeloid leukemia sources. Stem Cells (Dayton, Ohio) 2007;25(12):3111–3120. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Radich JP, Dai H, Mao M, Oehler V, Schelter J, Druker B, Sawyers C, Shah N, Stock W, Willman CL, Friend S, Linsley PS. Gene expression changes associated with progression and response in chronic myeloid leukemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(8):2794–2799. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510423103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anderson KM, Seed T, Plate JM, Jajeh A, Meng J, Harris JE. Selective inhibitors of 5-lipoxygenase reduce CML blast cell proliferation and induce limited differentiation and apoptosis. Leuk Res. 1995;19(11):789–801. doi: 10.1016/0145-2126(95)00043-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen Y, Hu Y, Zhang H, Peng C, Li S. Loss of the Alox5 gene impairs leukemia stem cells and prevents chronic myeloid leukemia. Nature Genetic. 2009;41(7):783–792. doi: 10.1038/ng.389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Knapp HR. Reduced allergen-induced nasal congestion and leukotriene synthesis with an orally active 5-lipoxygenase inhibitor. N Engl J Med. 1990;323(25):1745–1748. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199012203232506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scheibel T, Buchner J. The Hsp90 complex--a super-chaperone machine as a novel drug target. Biochem Pharmacol. 1998;56(6):675–682. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(98)00120-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Solit DB, Zheng FF, Drobnjak M, Munster PN, Higgins B, Verbel D, Heller G, Tong W, Cordon-Cardo C, Agus DB, Scher HI, Rosen N. 17-Allylamino-17-demethoxygeldanamycin induces the degradation of androgen receptor and HER-2/neu and inhibits the growth of prostate cancer xenografts. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8(5):986–993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Whitesell L, Mimnaugh EG, De Costa B, Myers CE, Neckers LM. Inhibition of heat shock protein HSP90-pp60v-src heteroprotein complex formation by benzoquinone ansamycins: essential role for stress proteins in oncogenic transformation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91(18):8324–8328. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.18.8324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.An WG, Schulte TW, Neckers LM. The heat shock protein 90 antagonist geldanamycin alters chaperone association with p210bcr-abl and v-src proteins before their degradation by the proteasome. Cell Growth Differ. 2000;11(7):355–360. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nimmanapalli R, O’Bryan E, Bhalla K. Geldanamycin and its analogue 17-allylamino-17-demethoxygeldanamycin lowers Bcr-Abl levels and induces apoptosis and differentiation of Bcr-Abl-positive human leukemic blasts. Cancer Res. 2001;61(5):1799–1804. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ge J, Normant E, Porter JR, Ali JA, Dembski MS, Gao Y, Georges AT, Grenier L, Pak RH, Patterson J, Sydor JR, Tibbitts TT, Tong JK, Adams J, Palombella VJ. Design, synthesis, and biological evaluation of hydroquinone derivatives of 17-amino-17-demethoxygeldanamycin as potent, water-soluble inhibitors of Hsp90. J Med Chem. 2006;49(15):4606–4615. doi: 10.1021/jm0603116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gorre ME, Ellwood-Yen K, Chiosis G, Rosen N, Sawyers CL. BCR-ABL point mutants isolated from patients with imatinib mesylate-resistant chronic myeloid leukemia remain sensitive to inhibitors of the BCR-ABL chaperone heat shock protein 90. Blood. 2002;100(8):3041–3044. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-05-1361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peng C, Brain J, Hu Y, Goodrich A, Kong L, Grayzel D, Pak R, Read M, Li S. Inhibition of heat shock protein 90 prolongs survival of mice with BCR-ABL-T315I-induced leukemia and suppresses leukemic stem cells. Blood. 2007;110(2):678–685. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-10-054098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kantarjian HM, Talpaz M, Santini V, Murgo A, Cheson B, O’Brien SM. Homoharringtonine: history, current research, and future direction. Cancer. 2001;92(6):1591–1605. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010915)92:6<1591::aid-cncr1485>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Luo CY, Tang JY, Wang YP. Homoharringtonine: a new treatment option for myeloid leukemia. Hematololy. 2004;9(4):259–270. doi: 10.1080/10245330410001714194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Quintas-Cardama A, Kantarjian H, Garcia-Manero G, O’Brien S, Faderl S, Estrov Z, Giles F, Murgo A, Ladie N, Verstovsek S, Cortes J. Phase I/II study of subcutaneous homoharringtonine in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia who have failed prior therapy. Cancer. 2007;109(2):248–255. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen Y, Hu Y, Michaels S, Segal D, Brown D, Li S. Inhibitory effects of omacetaxine on leukemic stem cells and BCR-ABL-induced chronic myeloid leukemia and acute lymphoblastic leukemia in mice. Leukemia. 2009;23(8):1446–1454. doi: 10.1038/leu.2009.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Legros L, Hayette S, Nicolini FE, Raynaud S, Chabane K, Magaud JP, Cassuto JP, Michallet M. BCR-ABL(T315I) transcript disappearance in an imatinib-resistant CML patient treated with homoharringtonine: a new therapeutic challenge? Leukemia. 2007;21(10):2204–2206. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Taipale J, Beachy PA. The Hedgehog and Wnt signalling pathways in cancer. Nature. 2001;411(6835):349–354. doi: 10.1038/35077219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhao C, Chen A, Jamieson CH, Fereshteh M, Abrahamsson A, Blum J, Kwon HY, Kim J, Chute JP, Rizzieri D, Munchhof M, VanArsdale T, Beachy PA, Reya T. Hedgehog signalling is essential for maintenance of cancer stem cells in myeloid leukaemia. Nature. 2009;458(7239):776–779. doi: 10.1038/nature07737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen JK, Taipale J, Cooper MK, Beachy PA. Inhibition of Hedgehog signaling by direct binding of cyclopamine to Smoothened. Genes Dev. 2002;16(21):2743–2748. doi: 10.1101/gad.1025302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dlugosz AA, Talpaz M. Following the hedgehog to new cancer therapies. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(12):1202–1205. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe0906092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Manne V, Lee FY, Bol DK, Gullo-Brown J, Fairchild CR, Lombardo LJ, Smykla RA, Vite GD, Wen ML, Yu C, Wong TW, Hunt JT. Apoptotic and cytostatic farnesyltransferase inhibitors have distinct pharmacology and efficacy profiles in tumor models. Cancer Res. 2004;64(11):3974–3980. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-3849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pellicano F, Copland M, Jorgensen HG, Mountford J, Leber B, Holyoake TL. BMS-214662 induces mitochondrial apoptosis in CML stem/progenitor cells, including CD34+38- cells, through activation of protein kinase C{beta} Blood. 2009 doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-05-219550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Copland M, Pellicano F, Richmond L, Allan EK, Hamilton A, Lee FY, Weinmann R, Holyoake TL. BMS-214662 potently induces apoptosis of chronic myeloid leukemia stem and progenitor cells and synergizes with tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Blood. 2008;111(5):2843–2853. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-09-112573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]