Abstract

The gene valC encoding an enzyme homologous to the 2-epi-5-epi-valiolone kinase (AcbM) of the acarbose biosynthetic pathway was identified in the validamycin A biosynthetic gene cluster. Inactivation of valC resulted in mutants that lack the ability to produce validamycin A. Complementation experiments with a replicating plasmid harboring full-length valC restored the production of validamycin A, suggesting a critical function of valC in validamycin biosynthesis. In vitro characterization of ValC revealed a new type of C7-cyclitol kinase, which phosphorylates valienone and validone, but not 2-epi-5-epi-valiolone, 5-epi-valiolone, and glucose, to their 7-phosphate derivatives. The results provide new insights about this enzyme activity and also confirm the existence of two different pathways leading to the same end-product, the valienamine moiety of acarbose and validamycin A.

Keywords: biosynthesis, validamycin, cyclitols, C7-cyclitol kinase, ValC

Introduction

Natural products of the C7N aminocyclitol family, represented by the anti-diabetic agent acarbose and the antifungal antibiotic validamycin A, are widely used for the treatment of human and plant diseases.[1] Their chemical structures most commonly contain an unsaturated aminocyclitol moiety, valienamine, which is responsible for their biological activities. Valienamine is also a precursor for the semisynthesis of voglibose, a clinically important anti-diabetic drug.[2, 3] Although several syntheses of valienamine have been reported,[1] the current supply of this compound remains heavily dependent on the degradation of validamycin A, which is produced by the soil bacteria Streptomyces hygroscopicus var. jinggangensis 5008 and S. hygroscopicus var. limoneus.[4] Validamycin A is used extensively in the Far East as a crop protectant, particularly for the treatment of sheath blight disease of rice plants and damping-off of vegetables caused by the fungus Rhizoctonia solani (Pellicularia sasakii).[5, 6]

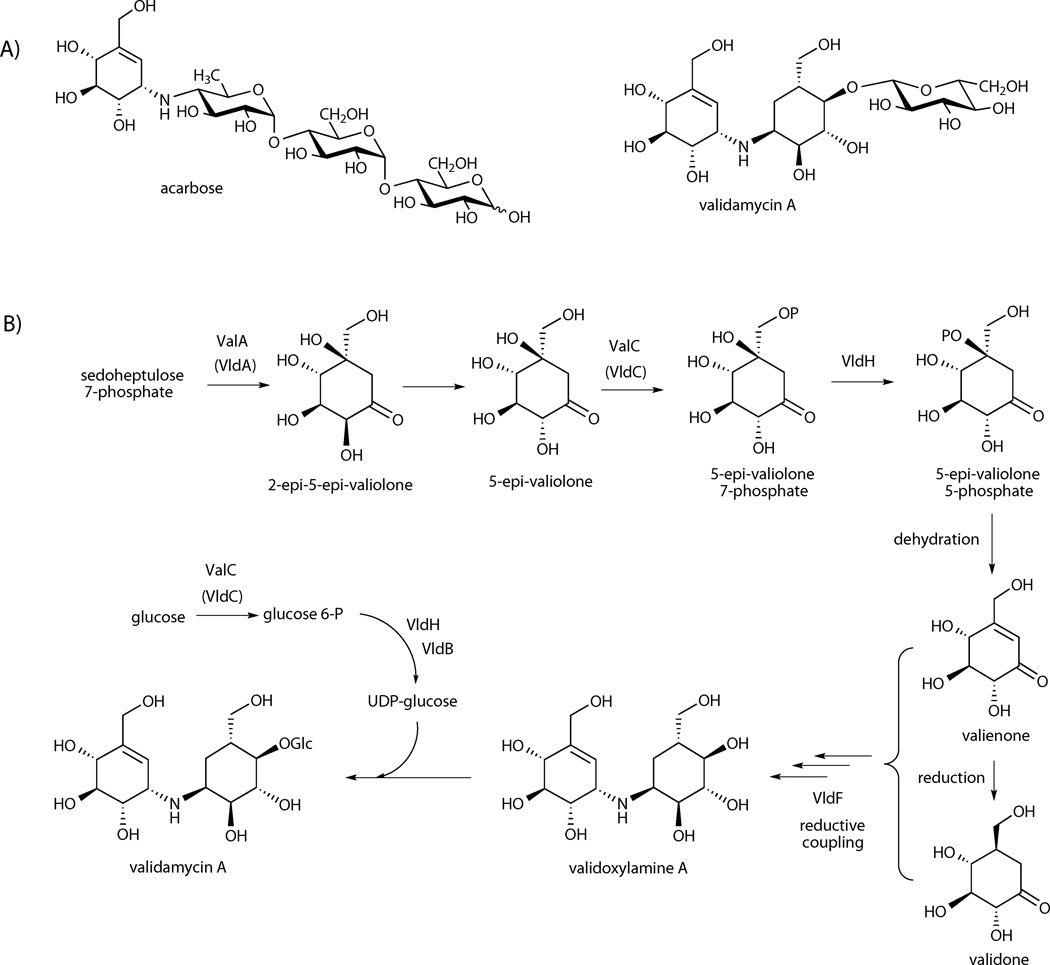

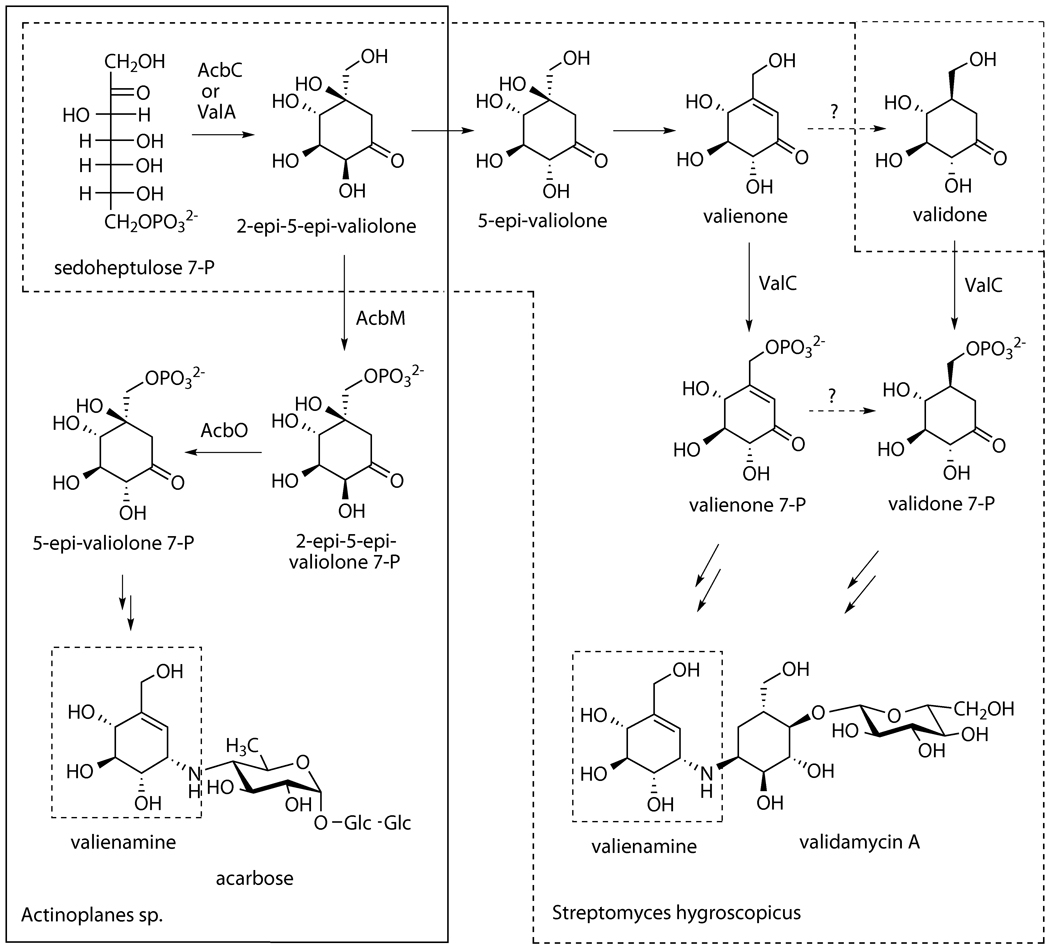

The valienamine moieties in both acarbose and validamycin A are derived from the same precursor, d-sedoheptulose 7-phosphate, via the cyclic product 2-epi-5-epi-valiolone.[7–10] However, further downstream their biosynthetic pathways appear to be different, which spawned some discussions regarding these two pathways.[10–13] Feeding experiments with isotopically labeled precursors to the validamycin and the acarbose producing strains revealed the incorporation of 2-epi-5-epi-valiolone, 5-epi-valiolone, valienone, and validone into validamycin A,[9] while only 2-epi-5-epi-valiolone was incorporated into acarbose (Scheme 1).[7] Based on the results of feeding experiments, it was proposed that in validamycin A biosynthesis 2-epi-5-epi-valiolone is epimerized at the C-2 stereocenter followed by dehydration between C-5 and C-6 to give valienone. The latter compound was found to be a common precursor for both the unsaturated and saturated cyclitol moieties of validamycin A.[9] Subsequently, the Piepersberg group reported the identification of a kinase (AcbM) in the acarbose pathway that converts 2-epi-5-epi-valiolone to its 7-phosphate derivative,[11] which suggests that further reactions in the acarbose pathway involve phosphorylated intermediates.

Scheme 1.

A) Chemical structures of acarbose and validamycin A, B) proposed biosynthetic pathway to validamycin A and functions of ValC/VldC reported by Suh.[13] VldH was proposed to be a phosphomutase.

We have recently reported the complete sequence of the validamycin A biosynthetic gene cluster from S. hygroscopicus var. jinggangensis 5008, revealing the presence of 16 structural genes of which only eight were found to be directly involved in the biosynthesis of validamycin A.[12, 14] These include the 2-epi-5-epi-valiolone synthase gene (valA), which encodes a dehydroquinate (DHQ) synthase-like protein that catalyzes the conversion of D-sedoheptulose 7-phosphate to 2-epi-5-epi-valiolone, and a gene (valC) that encodes a protein similar to AcbM, a phosphotransferase operating in the acarbose pathway, that converts 2-epi-5-epi-valiolone to its 7-phosphate derivative.[12, 14] Independently, two other validamycin gene clusters from related strains of bacteria, S. hygroscopicus 10–22 and S. hygroscopicus var limoneus KCCM 11405, have also been reported.[13, 15] Direct comparison of the validamycin cluster from S. hygroscopicus var. jinggangensis 5008 (the val cluster) and S. hygroscopicus var limoneus KCCM 11405 (the vld cluster) revealed that both clusters contain an almost identical set of genes necessary for the biosynthesis of validamycin. The presence of valC and vldC, homologs of acbM, in the val and vld clusters indicates the involvement of a kinase in validamycin A biosynthesis as well. However, because 2-epi-5-epi-valionone, 5-epi-valiolone, valienone, and validone were efficiently incorporated into validamycin A, the kinase should be able to activate all these cyclitols in order to facilitate their incorporation into the biosynthetic pathway. Alternatively, the kinase may only recognize valienone and/or validone as substrate, while 2-epi-5-epi-valionone and 5-epi-valiolone are involved in the pathway in their free forms. Suh and co-workers speculated that VldC is a 5-epi-valiolone 7-kinase that phosphorylates 5-epi-valiolone to its 7-phosphate derivative.[13] The latter compound is then converted to 5-epi-valiolone 5-phosphate by the action of a phosphomutase, setting the stage for a dehydration reaction to give valienone (Scheme 1B).[13] However, recent results from the same laboratories suggested that VldC is a glucokinase, which phosphorylates d-glucose to d-glucose 6-phosphate, and VldB is a d-glucose α-1-phosphate uridylyltransferase, leading to the notion that VldC and VldB are involved in the formation of UDP-glucose and the validamycin biosynthetic pathway does not recruit UDP-glucose from the primary metabolism, but rather exclusively utilizes UDP-glucose made by these enzymes.[16]

Herein we describe in vitro and in vivo functional studies of ValC, which provide new insights about its enzymatic activity and involvement in the biosynthesis of validamycin A, contrary to those reported by Suh and co-workers for VldC.[13, 16]

Results

Inactivation of valC in S. hygroscopicus abolishes the production of validamycin A

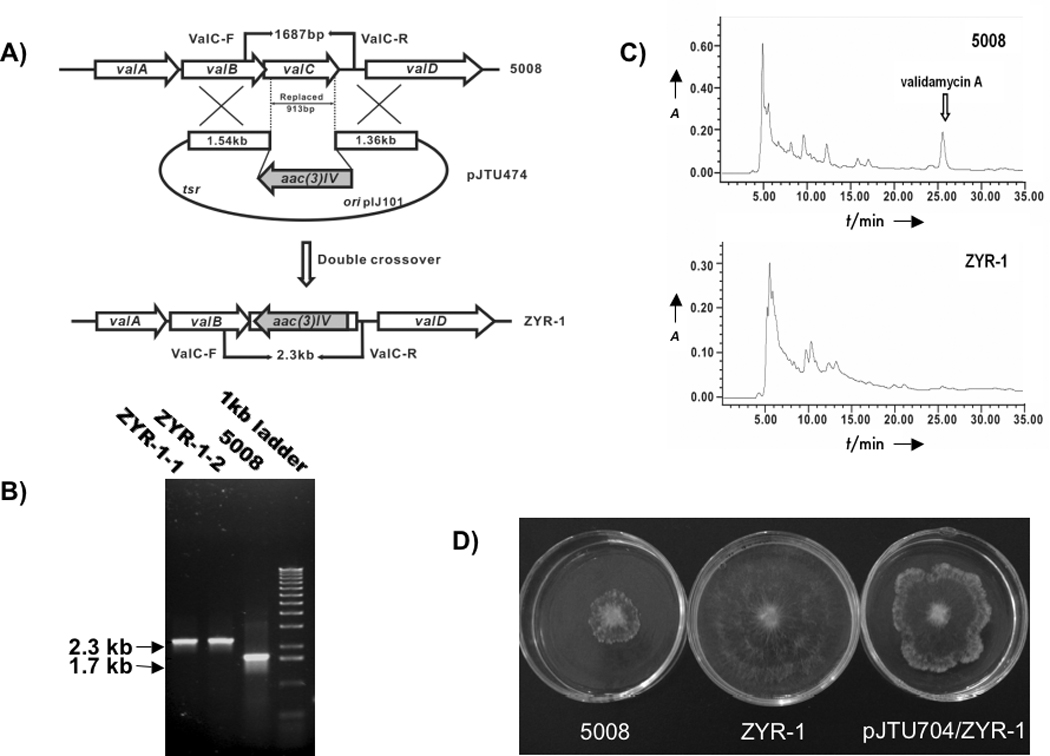

The involvement of valC in the biosynthesis of validamycin A was studied by inactivation of the gene through replacement of a 913 bp internal DNA fragment of valC with aac(3)IV[17] in S. hygroscopicus 5008. This was done by introducing pJTU474, a pHZ1358-derived plasmid in which aac(3)IV was inserted between sequences of 1.54-kb upstream and 1.36-kb downstream of the 913-bp DNA fragment, into wild-type strain 5008 by conjugation. Two ThioSAprR double recombinant mutants, ZYR-1-1 and ZYR-1-2, were chosen and total DNA from these mutants as well as from the wild-type strain 5008 was used as template for PCR amplifications using two oligonucleotide primers, ValC-F and ValC-R (Figure 1A). The two mutants gave a 2.3-kb PCR product, while the wild-type strain gave a 1.7-kb PCR product (Fig. 1B), which confirmed that a 913-bp DNA fragment internal to valC has been replaced by aac(3)IV in these mutants. The double recombinant mutant, ZYR-1, was then grown in production media for 6 days and the fermentation broth was analyzed by bioassay and HPLC. No inhibition of the fungus P. sasakii could be detected in the bioassay and no peak corresponding to validamycin A was detected by HPLC analysis, confirming a complete loss of validamycin A production in the mutant (Figure 1). Also, the mutant did not produce validoxylamine A, the aglycone of validamycin A, as one would expect if valC was exclusively involved in the synthesis of glucose 6-phosphate.

Figure 1.

Inactivation of valC in S. hygroscopicus 5008. A) Schematic representation of the replacement of a 913 bp internal fragment of valC with the 1.4 kb aac(3)IV. In shuttle plasmid pJTU474, aac(3)IV was inserted between 1.54 kb and 1.36 kb genomic fragments originally flanking the 913 bp region. While wild-type 5008 should give a 1.7 kb PCR-amplified product, mutant ZYR-1 should yield a 2.3 kb product using a pair of primers (ValC-F and ValC-R); B) PCR analysis of wild-type 5008 and mutant ZYR-1. PCR products were run on an agarose gel; C) HPLC comparison between cultures of the wild-type strain 5008 and the mutant ZYR-1. The peak corresponding to validamycin A is absent in mutant ZYR-1 cultures; D) Bioassay of fermentation broths of wild-type strain (5008), valC mutant (ZYR-1) and valC complemented mutant (ZYR-1/pJTU704). The agar plugs in the center of each plate are the indicator strain, Pellicularia sasakii. The fermentation supernatant of each sample was mixed with melted agar. The valC mutant did not produce validamycin A but regained the wild-type capability of producing the antibiotic after complementation with the shuttle plasmid pJTU704 carrying the full-length valC.

Restoration of validamycin production in ZYR-1 through complementation with recombinant valC

To confirm the critical role of valC in validamycin A biosynthesis, a complementation experiment was carried out by introducing plasmid pJTU704, a shuttle plasmid harboring valC under the control of the PermE* promoter, into ZYR-1 through conjugation. A 6-day old culture of ZYR-1/pJTU704 grown in the presence of thiostrepton was prepared and the supernatant was used for bioassay against P. sasakii. Although it was relatively less potent than the extract of the wild-type strain, the extract of ZYR-1/pJTU704 showed considerable activity, causing an abnormal branching at the tips and preventing further development of the fungus (Figure 1D). LC-MS experiments with the extracts revealed the production of validamycin A in ZYR-1/pJTU704, albeit in much reduced yields. The MS/MS analysis of the product showed a typical fragmentation pattern for validamycin A under positive-ion mode (m/z 498.1 [M+H]+, 336.1 [M+H−Glc]+, 178.1 [validamine+H]+), consistent with that reported previously.[12] This confirms the successful restoration of validamycin A production in ZYR-1/pJTU704, while similar complementation experiments with AcbM transferred into ZYR-1 did not restore the production of validamycin A (data not shown).

Synthesis of 2-epi-5-epi-valiolone, 5-epi-valiolone, valienone, and validone

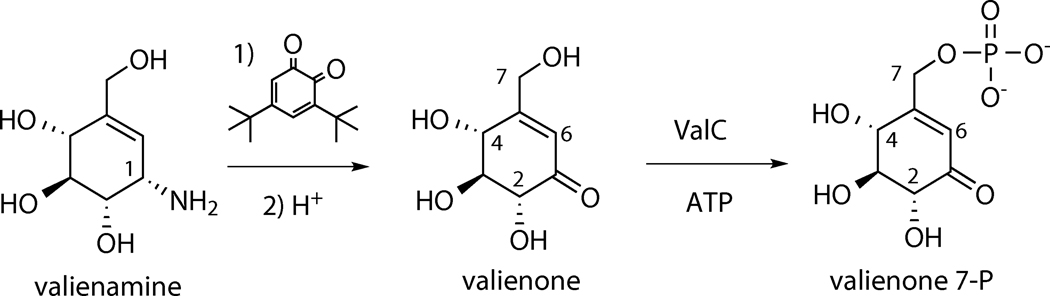

The incorporation of 2-epi-5-epi-valiolone, 5-epi-valiolone, valienone, and validone into validamycin A in the earlier feeding experiments[9] prompted us to investigate if any or all of these compounds can be phosphorylated by ValC. Therefore, all compounds were synthesized chemically and used as substrates for in vitro enzymatic investigations. The 2-epi-5-epi-valiolone, 5-epi-valiolone, and validone were synthesized from D-mannose, D-glucose, and valienamine, respectively, as reported previously.[7, 9, 18] Valienone was synthesized from valienamine by oxidative deamination using 3,5-di-tbutyl-1,2-benzoquinone and oxalic acid[19] in 80% yield (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of valienone and its conversion to valienone 7-phosphate catalyzed by ValC.

Overexpression of valC and enzymatic characterization of the gene product

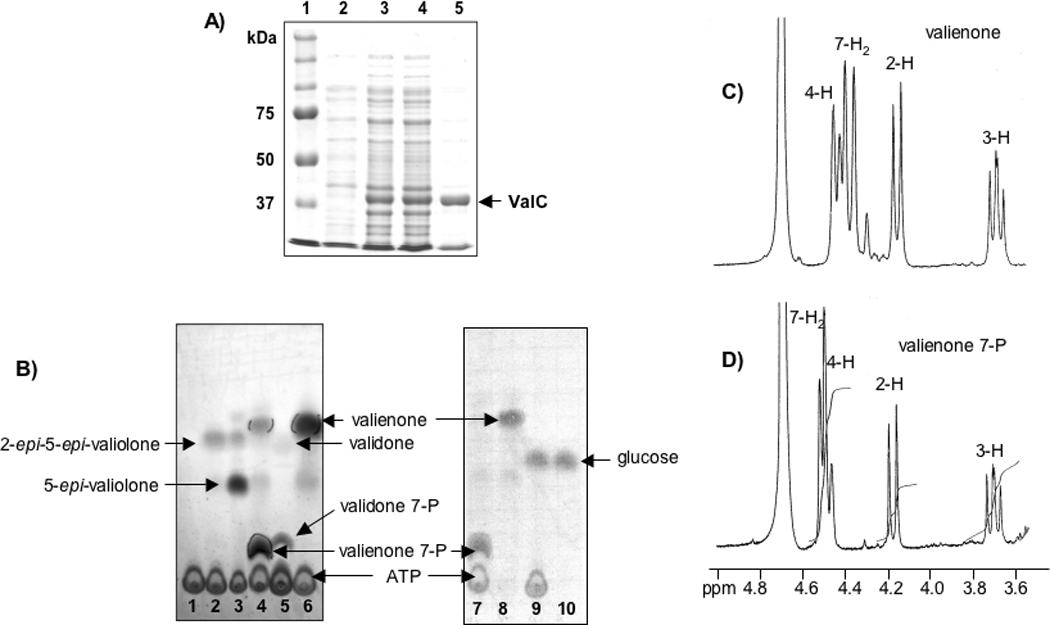

To explore the function of the presumed validamycin C7-cyclitol kinase ValC, the gene was amplified from cosmid 3G8[12] by PCR. The PCR product was cloned into the T7 expression vector pRSET-B and the resulting plasmid was introduced into E. coli BL21 Gold(DE3)pLysS by heat-pulse transformation. The expression of valC was induced with isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) to give a 40 kDa soluble His6-tagged protein, which was purified using a BD TALON™ affinity column. ValC consists of 361 amino acid residues with a calculated molecular weight of 36750 Dalton, which is consistent with the estimated size of the recombinant His6-tagged protein observed on the SDS PAGE gel (Figure 2). The enzyme was incubated with 2-epi-5-epi-valiolone, 5-epi-valiolone, valienone, and validone as substrates. Enzymatic reactions were carried out in the presence of ATP at 28 °C for 3–12 h and the products were analyzed by TLC and ESI-MS. The results revealed that ValC only catalyzes the phosphorylation of valienone and validone, but not 2-epi-5-epi-valiolone or 5-epi-valiolone (Figure 2B). As ValC is also distantly related to sugar kinases/glucokinases, D-glucose, D-fructose, D-mannose, and D-mannitol were also tested as substrates (Table 1). However, none of these sugars were converted to the corresponding phosphorylated derivatives at a detectable level. This result contradicts the report by Kim and co-workers for VldC, which was claimed to have glucokinase activity.[16] Their conclusion was based on enzyme assay using glucose as substrate coupled with glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase, measuring the increase in UV absorption at 340 nm due to formation of NADPH, and on a direct analysis of the VldC product by TLC.[16] However, no spectral data to support the identity of the product were reported.

Figure 2.

Heterologous production and characterization of the C7-cyclitol kinase ValC. A) SDS-PAGE analysis of His6-tagged ValC protein. Lanes: 1, molecular weight marker; 2, soluble protein of extract of E. coli BL21 Gold(DE3)pLysS/pTMVC-1 before induction; 3, total protein of extract of E. coli BL21 Gold(DE3)pLysS/pTMVC-1 after induction with IPTG; 4, soluble protein of lane 3; 5, purified His6-tagged ValC; B) Thin-layer chromatography analyses of ValC assay mixtures (solvent system, n-butanol:ethanol:water, 9:7:4). Lanes: 1, ValC without substrate; 2, ValC with 2-epi-5-epi-valiolone and ATP; 3, ValC with 5-epi-valiolone and ATP; 4, ValC with valienone and ATP; 5, ValC with validone and ATP; 6, Boiled ValC with valienone and ATP; 7, ValC with valienone and ATP; 8, ValC with valienone without ATP; 9, ValC with d-glucose and ATP; 10, ValC with d-glucose without ATP; C) and D) Partial 1H NMR spectra of valienone and valienone 7-phosphate measured on a Bruker DPX-300.

Table 1.

Substrate Selectivity of ValC and Substrate Incorporation of Feeding Experiments

| Substrate | Phosphotransferase ActivityActivity of ValC |

Results of Feeding Experiments* |

|---|---|---|

| 2-epi-5-epi-valiolone | − | 12% incorporation |

| 5-epi-valiolone | − | 19% incorporation |

| valienone | + | 30% incorporation |

| validone | + | 15% incorporation |

| D-glucose | − | PPP |

| D-fructose | − | NA |

| D-mannose | − | PPP |

| D-mannitol | − | NA |

All phosphorylation assay for ValC was carried out as described in Materials and Methods; +, phosphorylation; −, no phosphorylation; PPP: indirectly incorporated into validamycin A via the pentose phosphate pathway;[23] NA: data not available.

Based on incorporation results of previous feeding experiments with isotopically labeled compounds into validamycin A.[9]

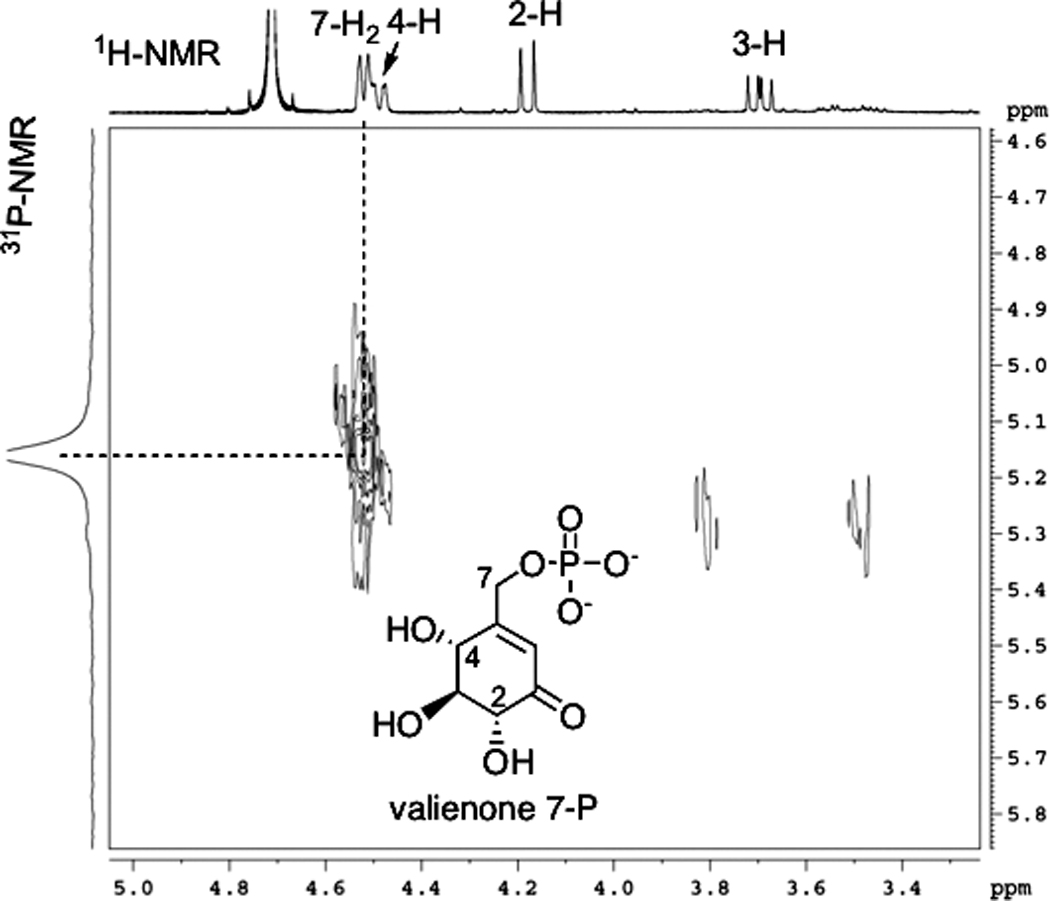

Identification of a ValC product

For the characterization of the ValC product, 3.5 mg of valienone was incubated with the enzyme and ATP and the product was purified using ion exchange (Dowex 1×8) and Sephadex G-10 columns and analyzed by ESI-MS and NMR. ESI-MS analysis of the product showed a major pseudo-molecular ion m/z 253 (M−H)−, which corresponds to the molecular mass of monophosphorylated valienone (MW=254). 1H-NMR analysis of the substrate (valienone) and the product revealed a shift of the C-7 methylene proton signal from an AB spin system (δ 4.29, 4.38 ppm; J = 18.5 Hz) in the substrate to a doublet (δ 4.52 ppm; 3JH-7,P = 7 Hz) in the product, while the signals of the other protons are relatively unchanged (Figures 2C and 2D). This suggests that the phosphorylation occurred regioselectively at 7-OH. The appearance of an asymmetrical broad triplet at 4.50 ppm in Figure 2D results from an overlap of the C-7 methylene protons signal with the H-4 signal (δ 4.49 ppm, dd, J = 2, 9 Hz). 1H-NMR data recorded at a higher magnetic field provided a better splitting pattern of the H-4 signal and an improved resolution between the H-4 and the C-7 methylene protons signals (Figure 3). The small coupling constant of the H-4 signal is due to a long-range coupling with the olefinic proton (δ 6.20 ppm, d, J = 2 Hz, H-6). The notion that the phosphorylation occurred at 7-OH was also supported by the 13C NMR data, in which a long-range 13C(6)-31P coupling and a shift of the C-7 signal were observed (see Supporting Information). The long-range 13C(7)-31P coupling was not visible in the spectrum due to line broadening applied during NMR data processing. Finally, a strong correlation between the H-7 and the phosphorous signals in the 1H-31P Correlation Spectroscopy (COSY) NMR spectrum provides compelling evidence to support the assignment of the phosphorylation site as the C-7 hydroxyl group, confirming the product of ValC as valienone 7-phosphate (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

1H-31P COSY of valienone 7-phosphate measured on a Bruker DRX-400. A strong correlation between the H-7 and the phosphorous signals supports the assignment of the phosphorylation site as the C-7 hydroxyl group.

Kinetic Properties of ValC

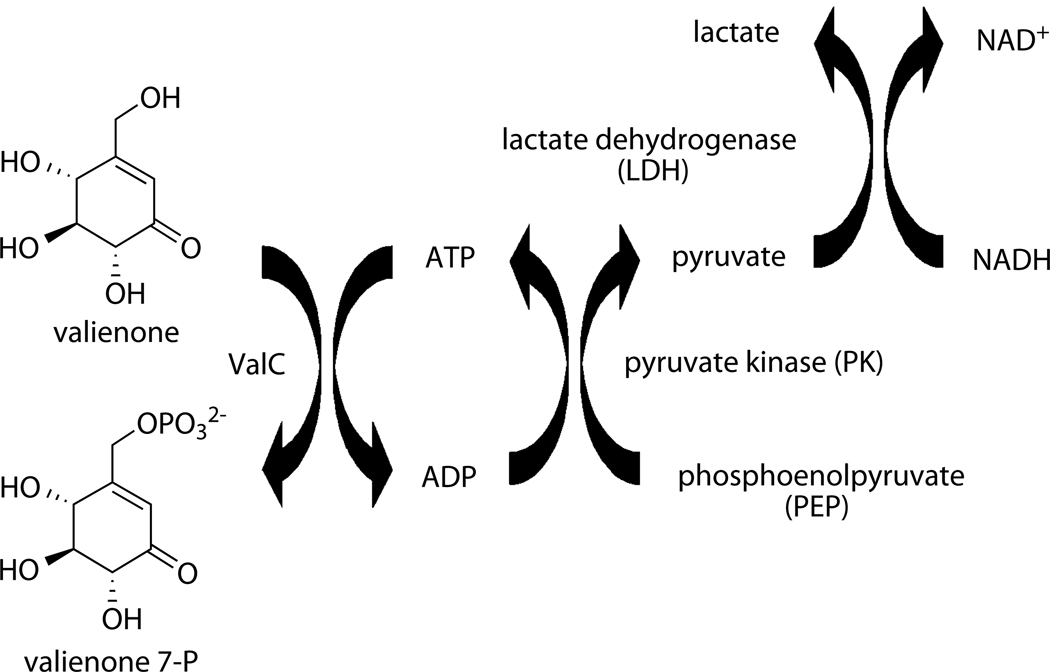

To investigate the substrate preference of ValC, kinetic properties of ValC for valienone and validone were characterized using the PK/LDH coupled enzyme assay system (Scheme 3).[20] Reactions were initiated by the addition of a saturating amount of ATP, and the oxidation of NADH to NAD+, which is stoichiometrically equivalent to the production of ADP, was measured by the decrease in A340. Surprisingly, under the experimental conditions the kinetic parameters for ValC with valienone (Km for valienone = 0.019 mM; Kcat = 3.5 s−1; Kcat/Km = 180 mM−1.s−1) were not substantially different from those with validone as substrate (Km for validone = 0.026 mM; Kcat = 7.3 s−1; Kcat/Km = 286 mM−1.s−1).

Scheme 3.

The PK/LDH coupled enzyme assay system used in the kinetic analysis of ValC.

Discussion

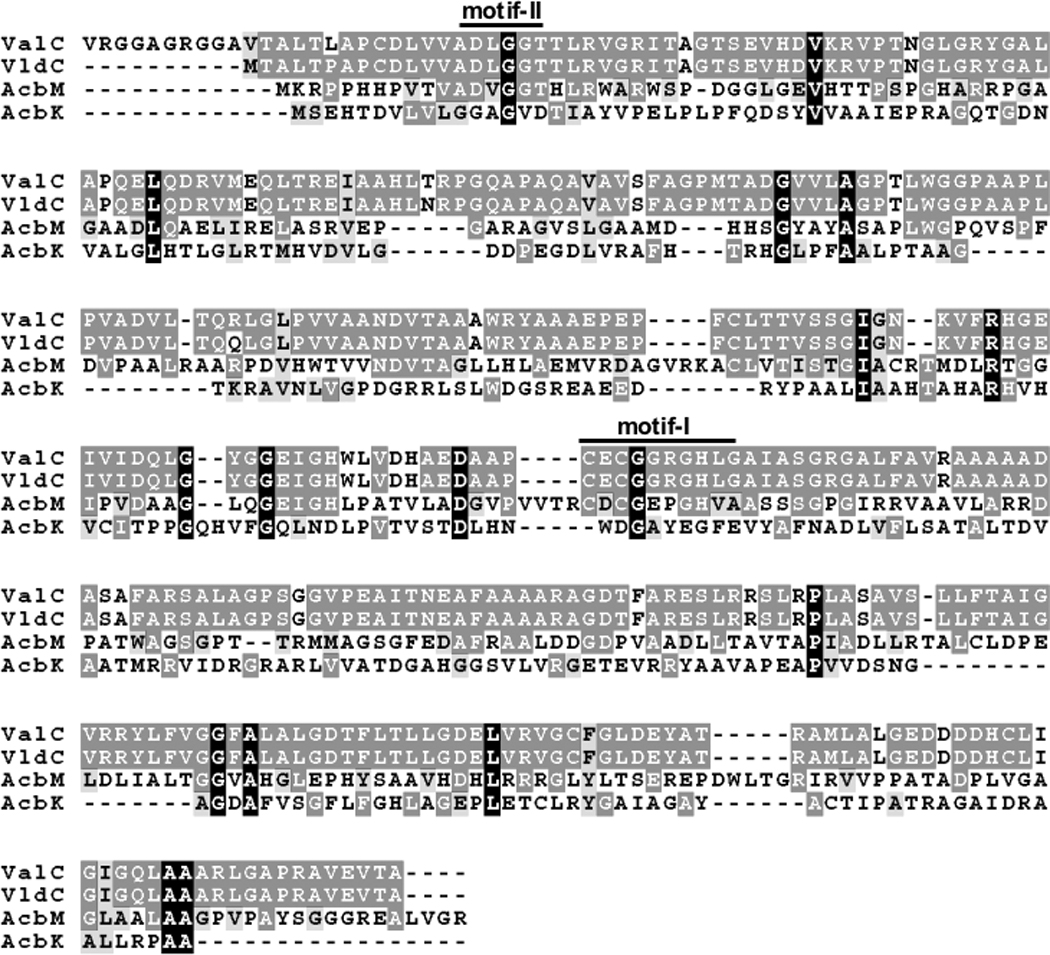

ValC is one of the relatively few C7-cyclitol kinases identified and characterized to date. The only related enzymes known so far are VldC[16] and the 2-epi-5-epi-valiolone kinase (AcbM).[11] While the amino acid sequence of ValC is almost identical (98% identity) with VldC, the homology between ValC and AcbM is relatively low (32% identity, 41% similarity). Results of a BLAST search also indicated a similarity between ValC and NagC, transcriptional regulator/sugar kinases (COG1940), and many bacterial glucokinases belonging to the ROK family (pfam00480). Bacterial glucokinases have been grouped into two different lineages with or without a conserved CXCGX(2)GCXE motif.[21] The first group is exemplified by the Bacillus subtilis glucokinase (GlcK), which contains the conserved motif, and the second group is exemplified by the Escherichia coli glucokinase (Glk), which lacks such a motif. ValC (VldC) and AcbM all contain the conserved motif, however, the last three amino acid residues (CXE) are replaced by HLG and HVA, respectively, which may be unique to mono C7-cyclitol kinases. Moreover, an ATP-binding motif D[ILV]G[GA][T][22] is also present in ValC (VldC) and AcbM (Figure 4). On the other hand, the acarbose 7-kinase (AcbK), which phosphorylates the OH-7 of the valienamine moiety of acarbose, lacks both of these conserved motifs.

Figure 4.

Multiple amino acid sequence alignment of C7-cyclitol kinases. ValC, valienone/validone kinase (S. hygroscopicus 5008); VldC, glucokinase (?) (S. hygroscopicus var. limoneus); AcbM, 2-epi-5-epi-valiolone kinase (Actinoplanes sp.); AcbK, acarbose kinase (Actinoplanes sp.). ValC, VldC and AcbM have the altered conserved CXCGX(2)GCXE motif (Motif I) and the ATP-binding motif D[ILV]G[GA][T] (Motif II).[22] However, the last three amino acid residues (CXE) of Motif I are replaced by HLG and HVA in ValC/VldC and AcbM, respectively. AcbK lacks both of these conserved motifs.

The results reported here favorably align with those of feeding experiments with isotopically labeled cyclitols,[7, 9] underscoring the existence of two different pathways leading to the same end-product, the valienamine moiety of acarbose and validamycin A, respectively. The divergence of the pathways seems to be due to the discrete substrate specificities of the kinases operating in the two systems. AcbM recognizes 2-epi-5-epi-valiolone as substrate, whereas in contrast, ValC phosphorylates valienone and validone, but not 2-epi-5-epi-valiolone or 5-epi-valiolone.

The substrate specificity of ValC for only valienone and validone, but not glucose and other sugars, strongly indicates its dedicated function in validamycin A biosynthesis. Inactivation of valC in the producer strain resulted in mutants that lack the ability to produce validamycin A, whereas complementing the disrupted gene with full-length valC restored the production of the antibiotic. Similar complementation experiments using acbM as a rescuing gene did not restore the production of validamycin A, suggesting that the expected AcbM product, 2-epi-5-epi-valiolone 7-phosphate, cannot be recognized by the downstream enzymes in the validamycin pathway. Interestingly, VldC, which is involved in validamycin biosynthesis in S. hygroscopicus var. limoneus and has 98% homology with ValC, has been reported to phosphorylate d-glucose to d-glucose 6-phosphate.[16] It is not clear at the moment if VldC would also recognize valienone and validone as substrates, and if substitution of a few amino acids residues in VldC resulted in its acceptance of d-glucose as substrate.

ValC, under the experimental conditions, catalyzed the phosphorylation of valienone and validone with almost identical catalytic rates. This result leads to two possible scenarios with respect to the pathway from valienone to the unsaturated and saturated cyclitol moieties of validamycin A (Scheme 4). First, a portion of valienone may be converted to validone, and both compounds phosphorylated by ValC. This notion aligns well with feeding experiments in which both valienone and validone were incorporated into validamycin A; valienone was incorporated into both the unsaturated and the saturated cyclitol moieties, whereas validone was incorporated into the saturated moiety only. Alternatively, valienone may be phosphorylated by ValC to valienone 7-phosphate, and a portion of it is then reduced by a yet to be identified reducing enzyme to validone 7-phosphate. Therefore, free validone may not be actually involved in the pathway. The incorporation of labeled validone during feeding experiments could be due to an unspecific activation of validone by ValC, the product of which can be recognized by the downstream enzyme (Scheme 4). Identification and characterization of reducing enzyme(s) involved in the pathway downstream of valienone and/or valienone 7-phosphate may shed more light on the involvement of validone in the pathway.

Scheme 4.

Proposed biosynthetic pathways to the valienamine moiety of acarbose and validamycin A

Experimental Section

General

The 1H, 13C, and 31P NMR spectra were recorded on Bruker DPX-300 or DRX-400 NMR spectrometers. Low-resolution electrospray ionization (ESI) mass spectra were recorded on a ThermoFinnigan Liquid Chromatograph-Ion Trap Mass Spectrometer. All synthetic reactions were carried out under an atmosphere of dry argon at room temperature in oven-dried glassware unless otherwise noted. Reactions were monitored by TLC (silica gel 60 F254, Merck) with detection by UV light, by alkaline permanganate spray or Ce(SO4)2/H2SO4 solution. Column chromatography was performed on 230–400 mesh silica gel (Aldrich), Dowex 50W × 8–200, Dowex 1×8 (Sigma) or Sephadex G-10 (Pharmacia). All chemicals were purchased from Aldrich or Sigma and used without further purification unless otherwise noted. HPLC for validamycin A analysis was run under the following conditions: solvent gradient of methanol/sodium phosphate buffer (5mM) from 0:100 to 5:95 % over 35 min; flow rate, 0.60 ml/min.

Strains and plasmids

As listed in Table 2 and Table 3.

Table 2.

Strains used in this study

| Strain | Relevant genotype/comments | Source/ref. |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli | ||

| DH10B | F− mcrA Δ (mrr- hsdRMS-mcrBC) ϕ80dlacZ ΔM15 ΔlacX74 deoR recA1 endA1 ara Δ139 D(ara,leu)1697 galU galK λ−rspL nupG | GibcoBRL |

| ET12567(pUZ8002) | dam dcm hsdS, pUZ8002 | [24] |

| XL-1Blue | recA1 endA1 gyrA96 thi-1 hsdR17 supE44 relA1 lac | Stratagene |

| BL-21 Gold(DE3)/pLysS | F− ompT hsdSB (rB− mB−) gal dcm (DE3) pLysS (Cmr) | [25] |

| S. hygroscopicus | ||

| 5008 | Wild-type producer of validamycin | |

| ZYR-1 | Non-producer of validamycin generated by replacing a 913-bp DNA fragment internal to valC | This work |

| ZYR-1/pJTU704 | ZYR complemented with pJTU704 harboring full-length valC | This work |

| Pellicularia sasakii | Fungal indicator strain sensitive to validamycin A | SJUSC |

Table 3.

Plasmids used in this study

| Plasmids | Relevant genotype/comments | Source/Ref. |

|---|---|---|

| pBluescript II SK(−) | bla, lacZ orif1 | Stratagene |

| pHZ1358 | Cosmid vector used for the construction of 5008 genomic library; pIJ101 derivative; tsr Ltz− sti+ oriT | [26] |

| PRSET-B | PT7 RBS 6xHis Xpress™ Epitope EK, bla | Invitrogen |

| pHGF9053 | bla, lacZ | Bai, unpublished |

| pJTU695 | tsr, bla, oriT, ori, pIJ101 derivative, PermE* | [14] |

| pJTU471 | Insertion of 1537 bp SacI-HindIII fragment overlapping the 5´-terminus and 1365 bp HindIII-KpnI fragment overlapping the 3´-teminus of valC into pHGF9053 digested with SacI and KpnI | This work |

| pJTU473 | Insertion of an 1.4 kb HindIII aac(3)IV gene fragment into the HindIII site sandwiched between the 1537 bp and 1365 bp fragments on pJTU471 | This work |

| pJTU474 | Insertion of a 4.3 kb BglII fragment from pJTU473, which contains a linked 1537 bp (left arm)-1.4 kb aac(3)IV-1365-bp (right arm) for valC inactivation, in BamHI site of pHZ1358 | This work |

| pJTU704 | Cloning of 1.08 kb NdeI-EcoRI valC fragment from pTMVC-1 to pJTU695 digested with NdeI and EcoRI | This work |

| pTMVC-1 | pRSET-B carrying a 1.08 kb full-length valC sequence | This work |

Construction of pJTU474 for targeted replacement of 913-bp DNA internal to valC

A 1537-bp SacI-HindIII fragment containing the N-terminus and a 1365-bp HindIII-KpnI fragment containing the C-terminus of valC were cloned into pHGF9053 digested with SacI and KpnI, which resulted in plasmid pJTU 471. A 1.4-kb HindIII fragment of aac(3)IV was then inserted into the HindIII site between the 1537-bp and 1365-bp fragments to generate pJTU473. Subsequently a 4.3-kb DNA, containing the 1537-bp fragment, the 1.4-kb aac(3)IV, and the 1365-bp fragment, was transferred as a BglII fragment from pJTU473 to BamHI-digested pHZ1358. The resulting plasmid, pJTU474, was used for targeted replacement of a 913-bp DNA fragment internal to valC with the 1.4-kb aac(3)IV in the wild-type strain 5008. The two oligonucleotide primers used for valC mutant confirmation were ValC-F (5´-ATCCGACGCTCGCGTTGAG-3´) and ValC-R (5´-CTCCACGGACAACGTCCTCG-3´).

PCR amplification was performed with Taq DNA polymerase (Shanghai Sangon) in a thermocycler (Hybaid, MBS) under the following conditions: initial denaturation at 94 °C for 5 min, then 10 cycles with denaturation at 94 °C for 1 min, annealing at 60 °C for 45 s, and extension at 72 °C for 2 min, were followed by 20 cycles with denaturation at 94 °C for 45 s, annealing at 55 °C for 45 s, and extension at 72 °C for 2 min. A last elongation step was done at 72 °C for 5 min. The PCR product was analyzed by gel electrophoresis.

Construction of pJTU704 and Complementation Experiments

A 1.08 kb NdeI-EcoRI fragment from the expression plasmid harboring a full-length valC (pTMVC-1) was ligated to the NdeI-EcoRI-digested vector pJTU695 to give pJTU704. The plasmid was transferred into E. coli ET12567 (pUZ8002) and introduced into ZYR-1 through conjugation. The transformants were selected with thiostrepton. A 6-day old culture of ZYR-1/pJTU704 grown in the presence of thiostrepton was prepared and the supernatant was used for bioassay against Pellicularia sasakii.

Synthesis of valienone

3,5-Di-tert-butyl-1,2-benzoquinone (242 mg, 1.1 mmol) was added to a solution of valienamine (175 mg, 1 mmol) in CH3OH (5 mL) and the mixture was stirred at room temperature (rt) for 30 min or until the color changes from dark brown to yellow. Water (5 mL) and tetrahydrofuran (5 mL) were added to the mixture to give a clear solution and the pH of the solution was adjusted to about 3 by addition of crystalline oxalic acid dihydrate. The acid solution was stirred at rt for 1.5 h and neutralized by addition of NaOH (1 M). The organic solvents were evaporated in vacuo and the remaining aqueous layer was washed three times with Et2O and lyophilized. The residue was further purified over Dowex 50W × 8–200 (H+) and silica gel columns, eluted with H2O and n-BuOH:EtOH:H2O (9:7:4), respectively, to give valienone (140 mg, 80% yield) as confirmed by its 1H NMR data.[7]

Cloning and overexpression of valC

The valC gene was amplified by PCR with Platinum® Pfx DNA polymerase (Invitrogen) using the cosmid clone 3G8 as template and primers ValCF3 5´-GAAGATCTGCATATGACGGCACTTACCCTCGCGC-3´ (engineered BglII and NdeI sites are underlined) and ValCR2 5´-GGAATTCTCATGCCGTCACCTCGACGGCCCGG-3´ (engineered EcoRI site is underlined). The natural start codon (GTG) was replaced with ATG to create an NdeI site right in the beginning of the gene, which would be useful if the removal of the 6×Histag sequence becomes necessary. The PCR amplification was carried out in a thermocycler (Eppendorf, Mastercycler gradient) under the following conditions: 33 cycles of 90 s at 95 °C, 45 s at 60 °C, and 45 s at 72 °C. The PCR products were digested with BglII and EcoRI, and subsequently ligated into BamHI/EcoRI-digested pRSET-B to generate pTMVC-1, which was sequentially verified and introduced by heat-pulse transformation into E. coli BL21 Gold(DE3)/pLysS (Stratagene). The transformants were grown in 20 mL of LB medium containing ampicillin (100 µg.mL−1) and chloramphenicol (25 µg.mL−1) at 37 °C to an OD600 of 0.6. Isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) was then added to a final concentration of 0.2 mM and the incubation was continued at 28 °C for 24 h. The cells were harvested by centrifugation at 3500 rpm for 15 min and stored frozen at −80 °C until further use.

Preparation of Cell-free Extracts and Purification of His6-tagged ValC

Cells were thawed and resuspended in disruption buffer (NaH2PO4 (50 mM), NaCl (300 mM), imidazole (10 mM), pH 8.0), the suspension was sonicated three times for 15 s each and cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 10,000 rpm for 10 min. The protein solution was applied to a BD TALONspin™ column (BD Biosciences) and centrifuged at 500 rpm for 2 min. The column was washed with washing buffer (NaH2PO4 (50 mM), NaCl (300 mM), pH 8.0, twice, and NaH2PO4 (50 mM), NaCl (300 mM), imidazole (100 mM), pH 8.0). The His6-tagged protein was eluted with elution buffer (NaH2PO4 (50 mM), NaCl (300 mM), imidazole (500 mM), pH 8.0) and dialyzed for 24 h against 1 L of dialysis buffer (Tris-HCl (pH 7.6) (25 mM), MgCl2 (10 mM), NH4Cl (20 mM) and DTT (0.5 mM)). Protein concentration was measured by the Bradford protein microassay with bovine serum albumin as standard.

Enzymatic Assay of ValC

The protein solution (50 µL, 0.15 mg.mL−1) was incubated with substrate (5 mM) in a 100 µL total volume containing Tris-HCl (pH 7.6) (25 mM), MgCl2 (10 mM), NH4Cl (20 mM), ATP (10 mM), and KF (2 mM). 2-epi-5-epi-Valiolone, 5-epi-valiolone, valienone, validone, d-glucose, d-fructose, d-mannose, or d-mannitol were used as substrates. Enzymatic reactions were carried out at 28 °C for 3–12 h and the products were analyzed by TLC and ESI-MS.

For kinetic analysis of ValC, the PK/LDH coupled enzyme assay system[20] was used. The reactions were carried out in a 600 µL total volume containing Tris-HCl (pH 7.6) (25 mM), MgCl2 (5 mM), NH4Cl (10 mM), ATP (1 mM), phosphoenolpyruvate (0.4 mM), NADH (0.2 mM), PK/LDH mix (6 µL) (in glycerol (50% (w/v)), KCl (100 mM), HEPES (pH 7.0) (10 mM), EDTA (0.1 mM); Sigma), and substrate (0.003–0.5 mM). The oxidation of NADH to NAD+ was measured by the decrease in A340 using a Hitachi U-2000 spectrophotometer.

Purification and physicochemical analysis of valienone 7-phosphate

For complete characterization of the ValC reaction product, the enzyme reaction was carried out using 3.5 mg of valienone. The reaction product was applied to a MICROCON YM-10 (Amicon) and the flow through was subjected to Dowex 1×8 mesh 100–200 (Cl− form). The column was washed with H2O and the compounds were eluted with 10 mM, 24 mM, 50 mM, 100 mM, 250 mM NaCl. The reaction product was found in the 250 mM NaCl fractions, which were then pooled and lyophilized. The dry sample was dissolved in H2O and desalted by passing it through a Sephadex G-10 column. The product was lyophilized to give valienone 7-phosphate (2.2 mg).

Valienone 7-phosphate: a white powder, ESI-MS: m/z 253 (M−H)−. 1H NMR (300 MHz, D2O, 300 K): δH 3.69 (1H, dd, J = 9, 11 Hz, H-3), 4.18 (1H, d, J = 11 Hz, H-2), 4.49 (1H, dd, J = 2, 9 Hz, H-4), 4.52 (2H, d, 3JH-7,P = 7 Hz, H-7a,b), 6.20 (d, J = 2 Hz, H-6). 13C NMR (75 MHz, D2O, 300 K): δC 63.3 (t, C-7), 72.1 (d, C-4), 76.5 (d, C-2), 77.2 (d, C-3), 121.9 (d, C-6), 164.7 (s, 3JC-5,P = 7.5 Hz, C-5), 200.2 (s, C-1).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank Professors H. G. Floss and P. M. Flatt for the critical reading of this manuscript, Shionogi & Co., LTD, Osaka, Japan for providing fellowship and research support to KM, and Steven Perry and Tommy Wang for technical help. This work was supported by NIH Grant AI-061528. Work at Shanghai Jiaotong University was supported by grants from the Ministry of Science and Technology (2003CB114205) and the National Science Foundation of China (30400004, 30570019).

Abbreviations

- aa

amino acid

- Thio

thiostrepton

- Apr

apramycin

- oriT

origin of transfer

- PermE*

up-mutated promoter of erythromycin resistance gene

- kDa

Kilo-Dalton

- ESI-MS

electrospray ionization-mass spectrometry

- IPTG

isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside

- DTT

dithiothreitol

- PK/LDH

pyruvate kinase/lactate dehydrogenase

REFERENCES

- 1.Mahmud T. Nat Prod Rep. 2003;20:137. doi: 10.1039/b205561a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goke B, Fuder H, Wieckhorst G, Theiss U, Stridde E, Littke T, Kleist P, Arnold R, Lucker PW. Digestion. 1995;56:493. doi: 10.1159/000201282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matsuo T, Odaka H, Ikeda H. Am J Clin Nutr. 1992;55:314S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/55.1.314s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Iwasa T, Kameda Y, Asai M, Horii S, Mizuno K. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 1971;24:119. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.24.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Asano N, Yamaguchi T, Kameda Y, Matsui K. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 1987;40:526. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.40.526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Robson GD, Kuhn PJ, Trinci AP. J Gen Microbiol. 1988;134:3187. doi: 10.1099/00221287-134-12-3187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mahmud T, Tornus I, Egelkrout E, Wolf E, Uy C, Floss HG, Lee S. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:6973. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stratmann A, Mahmud T, Lee S, Distler J, Floss HG, Piepersberg W. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:10889. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.16.10889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dong H, Mahmud T, Tornus I, Lee S, Floss HG. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:2733. doi: 10.1021/ja003643n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mahmud T, Lee S, Floss HG. Chem Rec. 2001;1:300. doi: 10.1002/tcr.1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang CS, Stratmann A, Block O, Bruckner R, Podeschwa M, Altenbach HJ, Wehmeier UF, Piepersberg W. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:22853. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202375200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bai L, Li L, Xu H, Minagawa K, Yu Y, Zhang Y, Zhou X, Floss HG, Mahmud T, Deng Z. Chem Biol. 2006;13:387. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2006.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singh D, Seo MJ, Kwon HJ, Rajkarnikar A, Kim KR, Kim SO, Suh JW. Gene. 2006;376:13. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2005.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yu Y, Bai L, Minagawa K, Jian X, Li L, Li J, Chen S, Cao E, Mahmud T, Floss HG, Zhou X, Deng Z. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71:5066. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.9.5066-5076.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jian X, Pang X, Yu Y, Zhou X, Deng Z. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 2006;90:29. doi: 10.1007/s10482-006-9058-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Seo MJ, Im EM, Singh D, Rajkarnikar A, Kwon HJ, Hyun CG, Suh JW, Pyun YR, Kim SO. J. Microbiol Biotechnol. 2006;16:1311. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hedges RW, Shannon KP. J Gen Microbiol. 1984;130:473. doi: 10.1099/00221287-130-3-473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mahmud T, Xu J, Choi YU. J Org Chem. 2001;66:5066. doi: 10.1021/jo0101003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Corey EJ, Achiwa K. J Am Chem Soc. 1969;91:1429. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tamura JK, Gellert M. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:21342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mesak LR, Mesak FM, Dahl MK. BMC Microbiol. 2004;4:6. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-4-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Veiga-da-Cunha M, Courtois S, Michel A, Gosselain E, Van Schaftingen E. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:6292. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.11.6292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Toyokuni T, Jin WZ, Rinehart KL., Jr J Am Chem Soc. 1987;109:3481. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Paget MS, Chamberlin L, Atrih A, Foster SJ, Buttner MJ. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:204. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.1.204-211.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moffatt BA, Studier FW. Cell. 1987;49:221. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90563-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sun Y, Zhou X, Liu J, Bao K, Zhang G, Tu G, Kieser T, Deng Z. Microbiology. 2002;148:361. doi: 10.1099/00221287-148-2-361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.