Abstract

The ability of clinicians to wage an effective war against many bacterial infections is increasingly being hampered by skyrocketing rates of antibiotic resistance. Indeed, antibiotic resistance is a significant problem for treatment of diseases caused by virtually all known infectious bacteria. The gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori is no exception to this rule. With more than 50% of the world’s population infected, H. pylori exacts a tremendous medical burden and represents an interesting paradigm for cancer development; it is the only bacterium that is currently recognized as a carcinogen. It is now firmly established that H. pylori infection is associated with diseases such as gastritis, peptic and duodenal ulceration and two forms of gastric cancer, gastric adenocarcinoma and mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma. With such a large percentage of the population infected, increasing rates of antibiotic resistance are particularly vexing for a treatment regime that is already fairly complicated; treatment consists of two antibiotics and a proton pump inhibitor. To date, resistance has been found to all primary and secondary lines of antibiotic treatment as well as to drugs used for rescue therapy.

The war between antibiotics and bacteria

The knowledge that bacteria were susceptible to antibiotics had its genesis in1877 with he first report by Pasteur and Joubert that a bacterium produced a toxic substance that killed other bacteria (cited in [1]). Fifty-two years later, penicillin was identified in 1929 as an antimicrobial by Fleming [2]. After it was shown that penicillin was able to prevent a lethal infection of streptococcus in mice [3] and to treat human disease [4, 5], it was thought that antibiotics would easily eliminate infectious disease. However, to everyone’s surprise, bacteria are strategic fighters, and have adapted to become resistant to a multitude of antibiotics used to treat infection. Because of this, it is no exaggeration to say that, on some fronts, bacteria are on the verge of winning the war.

Broadly defined, antibiotics are either natural or synthetic products that kill (bactericidal) or inhibit growth (bacteriostatic) of bacteria. Antibiotics must be selectively toxic for the microbe, and current drug classes target four key aspects of bacterial growth and physiology. The targets include bacterial cell wall synthesis, foliate coenzyme synthesis, protein synthesis, and nucleic acid (DNA or RNA) synthesis [6]. Bacterial antibiotic resistance mechanisms can similarly be broken into five major classes. These include alteration of the antibiotic target, enzymatic destruction of the antibiotic, enzymatic modification of the antibiotic, decreased permeability of the antibiotic, and increased efflux of the antibiotic from the bacterial cell (Table 1) [6].

Table 1.

Mechanism of resistance to each identified drug family as found in a typical bacterium and the currently identified mechanisms of resistance found in H. pylori.

| Antibiotic | Antibiotic Target | Typical Mechanisms of Resistance | H. pylori’s Mechanism of Resistance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Macrolides | 23S rRNA | Mutation of target or post transcriptional modification of target | Mutation of target |

| β-Lactams | PBP | Mutation of target, decreased permeability, increased efflux,β-lactamase | Mutation of target, decreased permeability |

| Nitroimidazoles | DNA | Mutation of bacterial nitroreductases, increased efflux | Mutation of bacterial nitroreductases, increased efflux |

| Tetracyclines | 30S ribosomal subunit | Mutation of target, increased efflux, mutation of ribosomal protection proteins | Mutation of target, increased efflux |

| Fluoroquinolones | toposoisomerase II (gyrase) or toposoisomerases IV | Mutation of gyrA or toposoimerase IV, increased efflux | Mutation of gyrA |

| Rifamycins | DNA-dependent RNA polymerase | Mutation of target | Mutation of target |

| Nitrofurans | DNA | Mutation of multiple bacterial nitroreductases | Mutation of multiple bacterial nitroreductases |

Introduction of the enemy: Helicobacter pylori

Helicobacter pylori was first isolated from patients suffering from chronic gastritis in 1982 [7]. H. pylori is a Gram-negative, spiral shaped bacterium that colonizes the arguably inhospitable niche of the stomach, and persists for the lifetime of the host, if untreated [8]. Additionally, H. pylori causes a wide range of diseases. This organism is associated with gastritis, 90% of all duodenal ulcers, 75% of all gastric ulcers [9], and two forms of stomach cancer, adenocarcinoma and MALT lymphoma [9–12]. Though infection rates show wide geographic distribution, this strategic bacterium chronically colonizes over 50% of the world’s population [13]. The high incidence of H. pylori infection likely contributes to the fact that gastric cancer mortality ranks second among all cancer deaths worldwide [14]. Due to the causal relationship between H. pylori and gastric malignancies, the World Health Organization classified H. pylori as a Class I carcinogen in 1994 [15]. Currently, H. pylori is the only bacterium to have achieved this perilous distinction.

During the relatively short period of time that we have known about H. pylori, there have been many different treatment regimens developed (reviewed in [16]. In fact, in 1994 there was a consensus from the National Institute of Health (USA) [17], followed two years later by the Maastricht Consensus from the European Helicobacter Study Group (Netherlands) [18], which established treatment recommendations to treat H. pylori infection. Given the increase in incidence of antibiotic resistance, the Maastricht Consensus report was updated in 2000 and again in 2005 to increase the effectiveness of treatment regimens against H. pylori [19, 20].

The current recommendation for first line therapy in locations where clarithromycin resistance is low, is a protein pump inhibitor, clarithromycin, and either metronidazole (first choice) or amoxicillin (second choice) for 14 days [20]. Additionally, these triple therapy regimens can be supplemented by the addition of bismuth in geographical areas where antibiotic resistance is high, though this combination is typically recommended as a second line therapy [20]. Moreover, since bismuth is not available in many countries, a combination of a proton pump inhibitor, metronidazole, and either amoxicillin or tetracycline is sometimes recommended [20].

Primary and secondary therapies are not always successful at eradicating H. pylori; therefore, there are many alternative drugs that are proposed for rescue therapy. These include fluoroquinolones (such as levofloxacin), rifamycins (such as rifabutin and rifampicin), nitrofurans (such as furazolidone) and other members (such as doxycycline) within families that are already used to treat H. pylori infection (reviewed in [16, 21]. Of note, resistance has been found to all utilized primary and secondary antibiotics, as well as, to many of the antimicrobials used for rescue therapy. This fact suggests that therapy success rates will continue to decline, and indicates that a detailed understanding of antibiotic resistance mechanisms may facilitate development of novel therapeutics. As such, the molecular mechanisms of H. pylori antimicrobial resistance are discussed in detail in this review (Table 2 and Figure 1).

Table 2.

Specific Antibiotic Resistance Mutations found in H. pylori.

| Antibiotic Class | Mechanism of resistance | Mutation | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Macrolides | Mutation of domain V of the 23S rRNA | A2142G | [22, 24, 27– 32] |

| A2142C | [33] | ||

| A2143G | [22, 24, 27– 32] | ||

| A2144T | [38] | ||

| T2182C | [37] | ||

| G2223A | [39] | ||

| C2244T | [39] | ||

| T2288C | [39] | ||

| Double mutation of A2115G and G2141A | [29, 41] | ||

| T2289C* | [39] | ||

| Mutation outside domain V of the 23S rRNA | T2717C | [42] | |

| Unknown | Unknown | [28, 42] | |

| β-Lactams | Mutation of penicillin/PBP4 complex | Unknown | [54, 55] |

| Mutation of PBP1 penicillin binding domain | Ala369Thr | [63] | |

| Val374Leu | [63] | ||

| Glu406Ala | [59] | ||

| Ser414Arg | [58, 63] | ||

| Ser417Thr | [59] | ||

| Leu423Phe | [63] | ||

| Thr438Met | [60] | ||

| Met515Ile | [59] | ||

| Asp535Asn | [59] | ||

| Ser543Arg | [59] | ||

| Thr556Ser | [59, 63] | ||

| Asn562Tyr | [59, 63] | ||

| Thr593Ala | [63] | ||

| Gly595Ser | [63] | ||

| Lys648Gln | [59] | ||

| Arg649Lys | [59] | ||

| Arg656Pro | [59] | ||

| Thr438Met | [60] | ||

| Mutation of PBP1 and PBP3 | PBP1: Ser414Arg, Leu423Phe, Asn562Try, and Thr593Ala PBP3: Ala499Val and Glu536Lys | [65] | |

| Mutation of PBP1, PBP2, and PBP3 | PBP1: Ser414Arg, Leu423Phe, Asn562Try, and Thr593Ala PBP2: Ala296Val, Asn/Ser494His, Ala/Val541Met, and Glu572Gly PBP3: Ala499Val and Glu536Lys | [65] | |

| Decrease membrane permeability | Mutations in Amino Acids 116–201 of hopB | [60] | |

| Stop codon at amino acid 211 of hopC | [60] | ||

| Nitroimidazoles | Inactivation of rdxA | Various mutations producing truncated RdxA | [73, 75–82, 177] |

| Mutation of rdxA | Arg16His | [80] | |

| Gln197Lys | [80] | ||

| Cys19Tyr | [77] | ||

| Tyr46His | [79] | ||

| Pro51Leu | [79] | ||

| Ala67Val | [79] | ||

| Ala80Thr | [80] | ||

| Double mutation of Ala80Thr and Val204Ile | [80] | ||

| Inactivation of frxA | Various mutations producing truncated FrxA | [84, 85] | |

| Missense mutations in frxA | Cys161Tyr | [85] | |

| Arg206His | [85] | ||

| Double mutation of Trp137Arg and Glu164Gly | [85] | ||

| Dual inactivation of frxA and rdxA | Various mutations producing truncated RdxA and FrxA | [77, 84, 85] | |

| Unknown | [83] | ||

| Dual inactivation of fdxB and rdxA | Unknown | [83] | |

| Tetracyclines | Mutation of primary tetracycline binding site in16S rRNA gene | Mutations of Nucleotides AGA926–928 TTC | [103–107] |

| Various single and double mutations of nucleotides 926–928 | [99, 105, 106, 108, 109] | ||

| Unknown | Unknown | [108, 109] | |

| Fluoroquinolones | Mutations in gyrA | Asn87Lys | [116–118] |

| Asn87Ile | [120] | ||

| Asn87Tyr | [120] | ||

| Ala88Val | [116–118] | ||

| Asp91Ala | [117] | ||

| Asp91Asn | [116–118] | ||

| Asp91Gly | [116–118] | ||

| Asp91Tyr | [116–118] | ||

| Double mutation of Ser83Ala and Asn87Lys | [118]. | ||

| Double mutation of Ala84Pro and Ala88Val | [118]. | ||

| Double mutation of Asn87His and Asp91Gly | [120] | ||

| Double mutation of amino acid Asp91Gly and Ala97Val or Ala97Asn** | [116, 118] | ||

| Double mutation of amino acid Asp91Asn and Ala97Val or Ala97Asn** | [116, 118] | ||

| Double mutation of amino acid Asp91Tyr and Ala97Val or Ala97Asn** | [116, 118] | ||

| Unknown | Unknown | [118] | |

| Rifamycins | Mutations in rpoB | Val149Phe | [128, 129] |

| Leu525Pro | [126] | ||

| Gln527Arg | [126, 127] | ||

| Gln527Lys | [126] | ||

| Asp530Asn | [126] | ||

| Asp530Val | [126, 127] | ||

| His540Asn | [126] | ||

| His540Tyr | [126, 127] | ||

| Ser545Leu | [126, 127] | ||

| Ile586Asn | [126] | ||

| Ile586Leu | [126] | ||

| Arg701His | [129] | ||

| Nitrofurans | Mutation in nitroreductases | Mutations in PorCDAB and OorDABC | [133] |

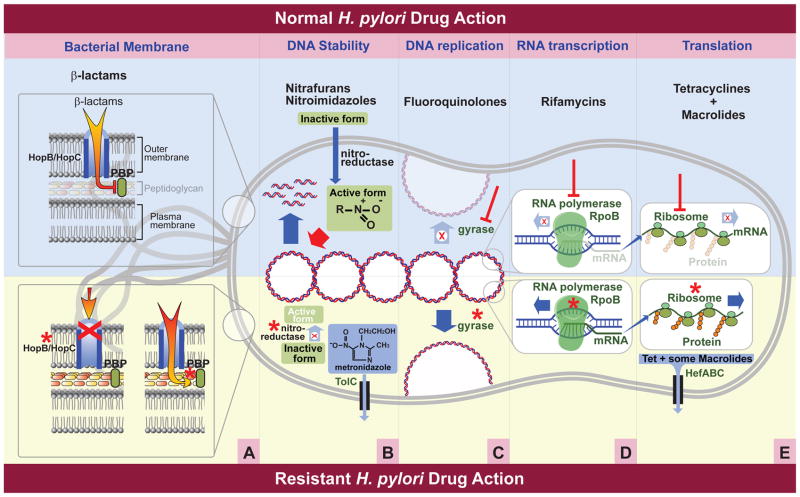

Figure 1.

Cellular components targeted by commonly used antibiotics and mechanisms of resistance utilized by H. pylori. The upper portion of the figure depicts normal drug interactions, while the lower portion depicts resistance mechanisms currently identified in H. pylori. * Denotes a mutation in the specified gene. A. β-lactams prevent the completion of the peptidoglycan layer of H. pylori through their interaction with penicillin binding proteins (PBP). Resistant bacteria contain either a mutated PBP, which prevents interaction with the β-lactams, or mutations in hopB or hopC, which decrease accumulation of the β-lactam within the bacterial cell. B. Nitrofurans and nitroimidizoles act in a similar manner against bacterial DNA. Both pro-drugs enter the cell and must be reduced by nitroreductases to become active. The activated form leads to formation of radicals that damage DNA. In resistant bacteria one or more of these nitroreductases are inactivated. The existence of a TolC efflux pump has also been identified as a mechanism of resistance to nitroimidizoles. C. Fluoroquinolones act upon gyrases, which are enzymes responsible for the conversion of DNA into a relaxed state required for DNA replication. Bacteria containing mutations in these gyrases are resistant to Fluoroquinolones. D. Rifamycins act by blocking a subunit of the DNA dependent RNA polymerase thereby terminating the production of mRNA. Resistant bacteria contain mutations within this subunit, which is encoded by the rpoB gene. E. Tetracyclines and macrolides both prevent the completion of translation, thereby preventing protein production. Mutations within specific ribosomal subunits cause H. pylori to be resistant to these drugs. Also, the HefABC efflux pump has been shown to remove tetracycline and some macrolides from the bacterial cell.

First Line Therapy and Resistance

Macrolides (primarily clarithromycin)

Clarithromycin is one of the first line therapy antibiotics used against H. pylori and is part of a class of broad spectrum antibiotics called macrolides [20]. Macrolides function to prevent protein translation. Specifically, these antibiotics interact with the bacterial ribosome and promote the premature release of peptidyl-tRNA from the acceptor site [22, 23].

Macrolide resistant H. pylori strains have been shown to be selected for during the course of treatment [24]. Moreover, clarithromycin resistance has been pinpointed to nucleotide mutations, the majority of which are single nucleotide mutations, in one of the two macrolide binding domains of the 23S rRNA [25, 26]. Most significant mutations are contained in Domain V of the 23S rRNA. In fact, this mechanism of clarithromycin resistance in H. pylori was first described in 1996 by Versalovic et al. Since the nomenclature for these mutations is confusing due to variation in the length of the 23S rRNA gene among strains, for this review we will employ the nomenclature for the 23S rRNA gene published by Taylor et al. [27]. At first, single nucleotide substitutions of an adenine to guanine at nucleotide positions 2142 (A2142G) and 2143 (A2143G), of the 23S rRNA were discovered [22]. Subsequently these same mutations were found in several other clarithromycin resistant strains [22, 24, 27–32]. Additional evidence that mutations within this domain are important for macrolide resistance in H. pylori came with the discovery that a transversion of an adenine to cytosine at position 2142 (A2142C) also conferred clarithromycin resistance [33]. In some studies as many as 91.4% of clarithromycin resistant strains contain the A2142G or the A2143G mutation [30]. Moreover, these are the predominant mutations found in Brazil [34], France [35], and Spain [36].

Other mutations within domain V of the 23S rRNA that have been identified to confer macrolide resistance include T2182C [37], A2144T [38], G2223A, C2244T, and T2288C [39], though the ability of the T2182C mutation to confer macrolide resistance remains in question, due to the fact that this mutation has been found in both resistant and sensitive strains [40]. The double mutation of A2115G and G2141A has also been demonstrated to confer resistance [29, 41].

Other important clarithromycin resistance mutations lay outside of domain V of the 23S rRNA. One such mutation, T2717C, results in low level clarithromycin resistance [42]. Additionally, other clarithromycin resistant H. pylori strains contain no mutations in the 23S rRNA [28, 42]. Though the exact mechanism remains undefined, this fact indicates another means of obtaining macrolide resistance. In other bacteria, macrolide resistance can occur through methylation of a specific adenine on the 23S rRNA [25, 43, 44]. This is achieved through the presence of rRNA methylases, termed erm genes (erythromycin resistance methylase) [43]. Despite the presence of clarithromycin resistance that is not associated with mutations of the 23S rRNA, scientists have failed to clone a single erythromycin resistance determinant from any H. pylori resistant isolate tested, and have failed to find genes with homology to any previously reported erm genes [29]. This has left the nature of this resistance in question. Interestingly, H. pylori has the ability to remove a different macrolide, erythromycin, via the HefABC efflux pump; however, H. pylori cannot efflux clarithromycin through this pump [45]. Based on the studies described above, it is clear that continued treatment of H. pylori with clarithromycin will likely lead to increasing rates of resistance, and may lead to resistance to multiple macrolides due to cross-resistance [29].

Beta-lactams (amoxicillin)

β-lactams are one of the best weapons clinicians have against H. pylori. The β-lactam antibiotics are subdivided into 5 groups. These include penicillins, cephalosporins, carbapenems, monobactams, and clavams [6]. All β-lactam antibiotics inhibit synthesis of the peptidoglycan layer of the bacterial cell wall. They do so by targeting penicillin binding proteins (PBPs) on the cytoplasmic membrane [46]. These PBPs are enzymes that carry out carboxypeptidation and transpeptidation, which are the terminal steps of peptidoglycan biosynthesis [46–48]. Broadly speaking, in other bacteria resistance to β-lactams arises by decreased membrane permeability of the drugs, increased efflux of the drug from the bacterial cell, modification of the PBPs that diminish the affinity of the drug for the protein, and the presence of β-lactamases that inactivate the antibiotic by hydrolyzing its ring structure [6].

Amoxicillin is a semi-synthetic penicillin that is currently the only β-lactam used to treat H. pylori infection. While initial treatment with amoxicillin suggested that it was very effective, amoxicillin resistance was documented in 1998, when the Hardenberg strain was isolated in Holland from an 82 year old dyspeptic patient [49]. Currently, amoxicillin resistance rates vary from as low as 0% to as high as 59% [50–53].

H. pylori contains nine putative penicillin binding proteins [54–56]. Of these, mutations of PBP1 [57–62] and PBP4 (also known as PBPD) [54, 55] have been shown to impact amoxicillin resistance. In terms of PBP4, a decreased amount of this protein was demonstrated to confer low level resistance to amoxicillin [55]. In fact, other resistant strains were confirmed to have no detectable PBP4 [54, 55].

In contrast, amino acid mutations in PBP1 can result in resistance due to decreased affinity for amoxicillin [57]. Studies have shown that most amino acid substitutions that result in resistance occur in the carboxy terminus of PBP1 in the penicillin binding domain [63]. For instance, PBP1 from the Hardenberg strain contains a single amino acid substitution of serine to arginine at position 414 (Ser414Arg) [58, 63]. Interestingly, Kwon et al. deduced that β-lactam resistance was acquired with multidrug resistance, and that 10 different amino acid substations in the PBP1 penicillin binding domain could confer resistance: Glu406Ala, Ser417Thr, Met515Ile, Asp535Asn, Ser543Arg, Thr556Ser, Asn562Tyr, Lys648Gln, Arg649Lys, and Arg656Pro [59]. Two of the previously described amino acid mutations (Thr556Ser [63, 64] and Asn562Tyr [63] were later confirmed, and additional amino acid mutations conferring resistance were identified; Ala369Thr, Val374Leu, Leu423Phe, Thr593Ala, and Gly595Ser [63]. Additionally, an in vitro study found that Thr438Met mutation is sufficient to cause resistance [60]. Another study showed that a nonsense mutation in the 3′ end was enough to confer resistance [64].

While mutations in PBP2 (ftsI) and PBP3 (pbp2) alone are enough to confer resistance to other β-lactams (ceftriaxone and ceftazidime), no mutations within either of these genes individually conferred resistance to amoxicillin [65]. However, combined mutations in PBP1 (Ser414Arg, Leu423Phe, Asn562Try, and Thr593Ala) and PBP3 (Ala499Val and Glu536Lys) yielded a higher level of resistance to amoxicillin [65]. Interestingly, even though mutations in PBP2 alone or in combination with mutations in PBP1 did not yield or increase amoxicillin resistance, respectively, the combination of mutations in PBP2 (Ala296Val, Asn/Ser494His, Ala/Val541Met, and Glu572Gly) worked synergistically with the aforementioned mutations found in PBP1 and PBP3 to confer an even greater level of amoxicillin resistance [65].

In addition to decreased amoxicillin binding [57], resistance can also result from mutations that decrease membrane permeability of the drug [47, 59, 61]. Mutations in two different outer membrane proteins have been proven to be sufficient to cause amoxicillin resistance [60]. These mutations include changes in amino acids 116–201 of hopB or a stop codon at amino acid 211 of hopC [60].

Nitroimidazoles, primarily metronidazole

Nitroimidazoles are synthesized as inactive prodrugs and require reduction inside the bacteria by specific non-human reductases to become active [66, 67]. In their active forms, nitroimidazoles produce toxic intermediates that result in DNA damage that kills the bacteria [66]. Metronidazole is a nitroimidazole that was efficiently used to treat H. pylori infection. However, H. pylori has adapted to be able to strategically escape the effectiveness of metronidazole treatment. Metronidazole resistance rates vary from 29–52% [68, 69] in some regions, and are as high as 100% in certain places [70].

The mechanism for metronidazole resistance in H. pylori is probably the most studied and most controversial topic concerning antibiotic resistance in the H. pylori field. Early studies showed that resistant strains accumulated metronidazole at a slower rate and to a lesser extent than sensitive strains, suggesting a role for transporters or efflux systems in resistance [71]. Other work suggested that mutations in recA might be responsible for resistance [72], but later studies found no evidence that mutations in recA lead to metronidazole resistance [73].

The first real breakthrough in understanding metronidazole resistance came with the discovery that resistant bacteria reduce other 5-nitroimidazole compounds more slowly than sensitive strains [74]. This indicated that resistance is a product of lack of reduction of the prodrugs [74]. Goodwin et al. showed that metronidazole’s toxicity depends on its reduction by the oxygen-insensitive, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) nitroreductase (rdxA), and that resistance arises from mutations that inactivate rdxA [75]. Specifically, a nonsense mutation caused the truncation of 14 amino acids, and other point mutations (both nonsense and missense) were found elsewhere in the rdxA gene [75].

Many other studies have identified specific mutations in rdxA that result in metronidazole resistance [73, 76–78]. The majority of these mutations result in a truncated RdxA protein [79–81]. Other resistant isolates have been identified that encode full length RdxA, but contain amino acid substitutions (Arg16His, Ala80Thr, Ala118Ser, Gln197Lys, Val204Ile [80], Tyr46His, Pro51Leu, Ala67Val [79], and Cys19Tyr [77]).

While inactivation of rdxA clearly causes metronidazole resistance, the association of specific amino acid mutations with resistance remains controversial, since very few studies made specific rdxA amino acid substitutions and then tested for resistance. Instead, resistant strains are often identified, and then rdxA is simply sequenced to identify changes and any differences are ascribed to impart metronidazole resistance, without distinguishing resistance-associated nucleotide mutations from natural genetic diversity. However, newer studies show that the majority of rdxA sequences were identical between susceptible and resistant strains, leading the authors to suggest that inactivation of RdxA is sufficient but not essential to obtain metronidazole resistance [78, 82]. This evidence, coupled with the fact that some resistant strains do not have mutations within the rdxA gene [76, 79, 83], suggests that other resistance mechanisms exist in H. pylori.

Kwon et al. were the first to discover that mutations in the NADPH flavin oxidoreductase gene (frxA) conferred metronidazole resistance [84]. Deletion mutations resulting in truncations of the frxA gene confer metronidazole resistance [84, 85], and missense mutations in frxA (Cys161Tyr, Arg206His, and a double mutation of Trp137Arg and Glu164Gly), without specific changes in rdxA, confer low level resistance [85]. High metronidazole resistance is conferred when both the frxA and rdxA genes are prematurely truncated, indicating a synergistic effect on resistance [77, 83–85]. In contrast to these studies, others have found that frxA inactivation does not significantly change susceptibility to metronidazole [86]. Also, the majority of resistant strains with mutations in frxA also have mutations in rdxA [87], and truncations of frxA have been identified in metronidazole sensitive H. pylori isolates [88]. These facts, combined with work that suggested that inactivation of frxA in a strain with a functional rdxA only slowed the bactericidal effects of metronidazole [87], has led some to suggest that a frxA mutation alone may not be enough to impart resistance [89].

Another controversy in the metronidazole field lies in the debate as to whether other genes besides rdxA and frxA may have a role in metronidazole resistance. Some metronidazole resistant isolates have functional rdxA and frxA with no identified mutations, indicating that there are other mechanisms leading to metronidazole resistance [90]. One area of study has focused on the roll of various Helicobacter pylori reductases in metronidazole resistance. It was found that disruption of the fdxB (ferredoxin-like protein) nitroreductase resulted in an increased level of metronidazole resistance in strains with an inactivated rdxA [83]. Other reductases, such as alkyl hydroperoxide reductase, AhpC [91], have been suggested to play a role in resistance since the expression levels of various isoforms of ahpC are increased when resistant strains are grown in the presence of metronidazole [92]. While thioredoxin reductase has been found to reduce metronidazole in at least one other organism [93], its role in metronidazole resistance in H. pylori is still unknown. However, an in vitro study showed that thioredoxin protein 1, trxA1, can be an electron donor for AhpC [94]. Finally, there is also evidence that an efflux pump (TolC) is responsible for metronidazole resistance. When two of four TolC homologs (HP0605 and HP0971) are mutated, it leads to an increase in susceptibility to metronidazole even though single-knockout mutants are still resistant [95]. Taken together, it is clear that rdxA and frxA mutations confer metronidazole resistance. However, the role of other genes and mutations require more thorough characterization.

Second Line Therapies and Resistance

Tetracyclines

Tetracyclines are often used as a second line therapy when H. pylori infections are not cured by the first line drug regimen. The tetracyclines include tetracycline, chlortetracycline, oxytetracycline, doxycycline, and tigilcycline [6]. Tetracyclines function by inhibiting bacterial protein synthesis. They do this by binding to the 30S ribosomal subunit and blocking the attachment of a new aminoacyl-tRNA to the ribosomal acceptor site [6, 96–98]. This effectively stops synthesis of bacterial peptides. However, since the interaction between the ribosome and the tetracycline is reversible, the antibiotic has a bacteriostatic effect [96, 97].

As with other drugs, resistance patterns to tetracyclines vary by geographic distribution: resistance rates are fairly low (0–7% in some areas) [99, 100], but higher in others (as high as 59% in China) [101]. Tetracycline resistance in H. pylori was first observed in 1996 [102], and primarily occurs through alteration of nucleotides within the primary tetracycline binding site [103]. For instance, a triple mutation in the 16S rRNA gene at nucleotides 926–928, from AGA to TTC, has been shown to confer high level tetracycline resistance and is found worldwide [103–107]. Additionally, single and double mutations in this region weaken the interaction of 16S RNA with tetracycline, and result in moderate resistance to tetracycline [99, 106, 108, 109].

While changes in the 16S rRNA sequence are the primary mechanism of tetracycline resistance, there are reports of weakly resistant H. pylori strains with no mutations in their 16S rRNA [108, 109]. Moreover, some of these tetracycline resistant strains demonstrate normal ribosome-tetracycline binding [108]. While the mechanism of resistances in these strains is unclear, some possible explanations include the presence of efflux pumps or mutations in various porin genes [109]. Putative efflux systems have been identified in H. pylori [110]. Although no observable tetracycline efflux activity was initially found [111], a later study found that the efflux pump, HefABC, actually does show efflux activity for tetracycline [45]. Additionally, mutations within this pump results in an increase in susceptibility to tetracycline [45].

Rescue/Salvage Therapy and Resistance

Fluoroquinolones

Some of the newer weapons used in the war against H. pylori are the fluoroquinolones. Fluoroquinolones include ciprofloxacin, gatifloxacin, sitafloxacin, moxifloxacin, temafloxacin, and levofloxacin. Currently, these drugs are used as rescue or salvage therapy, when both first and second line therapies have failed to eradicate infection. Fluoroquinolones target topoisomerase II (gyrase) or topoisomerase IV (a gyrase homologue) activity of bacterial cells [112]. Bacterial gyrases act by making cuts in DNA, thus allowing the nucleic acid strand to be in a relaxed orientation, where it is available for replication, recombination, and transcription [6]. Resistance mutations to ciprofloxacin, in other bacteria has been found in amino acids 67–106 of the gyraseA subunit [113]. Thus, this region has been deemed the “quinolone resistance determining region,” or the QRDR [114].

Fluoroquinolone resistance rates vary geographically to as low as 13.8% (Lisbon) [115] to between 21.5% and 33.8 % (depending on the fluoroquinolone) in Korea [116]. As with other bacteria, most quinolone resistance mutations in H. pylori are found within the QRDR. The first amino acid mutations identified were Asn87Lys, Ala88Val, Asp91Gly, Asp91Asn, Asp91Tyr [116–118], and a double mutation at amino acid Asp91 to a Gly, Asn, or Tyr combined with either a Ala97Val or Ala97Asn substitution [116, 118]. The Ala97Val mutation has subsequently been shown not to be associated with resistance when found alone [119]. Other double mutations identified as being important in fluoroquinolone resistance are Ala84Pro/Ala88Val and Ser83Ala/Asn87Lys [118]. Miyachi et al. found three new mutations causing levofloxacin resistance to be Asn87Ile, Asn87Tyr, and a double mutation of Asn87His and Asp91Gly [120]. Indeed, many studies have confirmed that the major mutation causing fluoroquinolone resistance occurs in gyrA at position 91 [116, 119, 121] or 87 [118, 120]: studies have shown that 95.7% of gatifloxacin resistant strains [121] and 83.3% of levofloxacin resistant strains [120] contains mutations at these residues.

Currently, only a single resistant strain has been identified that does not contain a mutation within the QRDR [118]. This discovery suggests that there are additional mechanisms of fluoroquinolone resistance in H. pylori. Common mechanisms of resistance found in other bacteria, such as efflux pumps and topoisomerase IV, appear not to apply here, since there is evidence that efflux pumps are not a strategy for antimicrobial resistance to fluoroquinolones in H. pylori [45, 111] and genes such as parC or parE are not found in the H. pylori genome [119, 122, 123]. Several studies have also looked at gyrB, but no mutations resulting in resistance were isolated [119–121]. Therefore, currently the alternative mechanism of resistance remains unknown, and further studies need to be completed to have a more inclusive understanding of fluoroquinolone resistance.

Rifamycins

Rifamycins, which consists of rifampicin and rifabutin, are used for rescue therapy. These drugs are bactericidal, due to the irreversible blockage of the DNA-dependent RNA polymerase [124]. While there are no prevalence studies for resistance to rifamycins, resistance is possible by mutation within the rpoB gene, which encodes the β-subunit of RNA polymerase [125]. Several different amino acids substitutions have been shown to confer rifamycin resistance: Leu525Pro, Gln527Lys [126], Gln527Arg, Asp530Val [126, 127], Asp530Asn [126], His540Tyr [126, 127], His540Asn [126], Ser545Leu [126, 127], Ile586Asn, and Ile586Leu [126]. Not surprisingly, these regions are also important for rifamycin resistance in E. coli and mycobacteria [126]. Other amino acids substitutions within rpoB that have been shown to be important for rifamycin resistance include Val149Phe [128, 129] and Arg701His [129].

Nitrofurans

Nitrofurans are prodrugs that become active when the nitro group is reduced by an oxygen-insensitive nitroreductase. This activation results in the production of electrophilic intermediates that cause DNA damage and attack bacterial ribosomal proteins, thus blocking protein synthesis and causing cell death [130–132]. Nitrofurans consist of furazolidone and nitrofurantoin. Prevalence of nitrofuran resistance has been shown to be between 1.6% [133] and 4% [51]. This low resistance rate could be attributable to the fact that nitrofurans are not widely used.

While the mechanism of action of these drugs are similar to 5-nitroimidazoles, resistance is not acquired through the same mechanisms. While 5-nitroimidazole (such as metronidazole) resistance arises from mutations within rdxA and frxA, knockouts of these genes did not produce resistance to furazolidone or nitrofurantoin [133]. This suggests that the nitrofurans could be used as an alternative to metronidazole [133].

It has been suggested that activation of the nitrofurans requires two reduction steps such as is the case in E. coli [131, 133]. Evidence for two reduction steps includes: the fact that in vitro serial passage does not produce any nitrofuran resistant strains [134] and that despite the fact that FrxA has the ability to reduce nitrofurans [135], knockouts of frxA do not confer nitrofuran resistance[133]. Additional nitroreductases suggested as having a role in nitrofuran resistance in H. pylori are pyruvate::flavodoxin oxidoreductase (PorCDAB) [133, 135] and 2-oxoglutarate oxidoreductase (OorDABC) [133]. When these genes are mutated, a low-level resistance is conferred to nitrofurans as well as to metronidazole [133]. If resistance is acquired in a two step mechanism, these antibiotics may be the next good weapon physicians have against H. pylori.

Alternative treatments methods

Characteristics of H. pylori, such as high colonization rates, longevity of infection, severity of associated diseases, and the ability to become resistant to varying antibiotics with diverse mechanisms of action, has led to investigation into alternative treatment methods. These alternatives include modifying diet or vitamin intake, developing a vaccine for H. pylori, and modifying existing treatment regimes. Modifications to diet or vitamin intake includes the addition of vitamin C supplements, which may reduce risk of gastric maladies [136–138] and H. pylori’s ability to colonize [139, 140], and prostaglandins (either taken directly or obtained through polyunsaturated fatty acids), which protect the gastric mucosa from damage [141–143].

Arguably the best option would be the production of a H. pylori vaccine, and several possible vaccine candidates are being researched [144–146]. Vaccine components vary and include killed H. pylori whole cell extracts [147], heat shock proteins [148], flagellar antigens [144], adhesion antigens [149], lipopolysaccharide antigens [150], neutrophil activating protein [151], and urease [152]. Unfortunately many of these are a long way from human trials [144–146], and the inactivated whole cell extract were proven ineffective in a human volunteer study [153].

In lieu of an affective vaccine, many new drugs have shown promise against H. pylori. For instance, other prodrugs use different primary reductases than metronidazole, providing an alternative to a drug that is ineffective in many areas [135]. Newer fluoroquinolones (sitafloxacin, HSR-903, gatifloxacin, Bay 12–8039, and trovafloxacin) [154–156] and new rifamycins (KRM-1657 and KRM-1648) [157] show in vitro activity against H. pylori at low concentrations, suggesting that they may be affective in vivo.

Modifications to current therapeutic regimes include the addition of lactoferrin, which has been proven to improve eradication rates when used with certain triple therapies [158] and lactobacillus, which has been proven to lower side effects of some antibiotics thus, potentially increasing patient compliance [159, 160]. A final possible modification to current therapeutic regimes is the addition of a metal, such as bismuth or cobalt II, to the treatment regimes. Bismuth compounds prolong antibiotic use by reducing resistance rates as well as producing a synergistic effect with several drugs [161, 162]. Cobalt II shows particular promise, as it is effective at 100 times lower concentrations than bismuth [163]. Along these lines, since two enzymes essential for colonization, hydrogenase and urease [164–167], require nickel for maturation [168–174] and there is no clear biochemical function for nickel in the human host [175], theoretically nickel chelation could be used as an effective antimicrobial agent.

H. pylori has evolved into a highly antimicrobial resistant pathogen, obtaining resistance to almost all first, second, and rescue therapy antibiotics. Scientists have been able to identify many of the molecular mechanisms that confer resistance (Table 2 and Figure 1). However, there are still some unknown resistance mechanisms to identify. While currently it may seem as if H. pylori is winning the war against antibiotics, hopefully new treatment options will improve eradication rate. Overall, it is clear that novel strategies, such as inhibitors of virulence factors [176], and drug development will be required to produce the tools to allow physicians to yet win the war against this strategic pathogen.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Beth Carpenter for critical reading of the manuscript, Jeannette Whitmire for literature review and Jang Gi Cho for assistance with Figure 1. Research in the laboratory of D. Scott Merrell is supported by AI065529 from NIAID and R073LA from USUHS. The contents of this work are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH or Department of Defense.

References

- 1.The Study of Antibiotics as a Lesson in Scientific Methods. Am J Public Health Nations Health. 1946;36:1310–3. doi: 10.2105/ajph.36.11.1310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fleming A. On the antibacterial action of cultures of a penicillium, with special reference to their use in the isolation of B. influenzae. Br J Exp Path. 1929;x:3–13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chain E, Florey HW, Gardner AD, et al. Penicillin as a Chemotherapeutic Agent. The Lancet. 1940;236:226–8. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abraham EP, Chain E, Fletcher CM, et al. Further Observations on Penicillin. The Lancet. 1941;238:177–89. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bennett JW, Chung KT. Alexander Fleming and the discovery of penicillin. Adv Appl Microbiol. 2001;49:163–84. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2164(01)49013-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Walsh C. Antibiotics: Actions, Origins, Resistance. Washington, DC: ASM Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marshall BJ, Warren JR. Unidentified curved bacilli in the stomach of patients with gastritis and peptic ulceration. Lancet. 1984;1:1311–5. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(84)91816-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blaser MJ. Epidemiology and pathophysiology of Campylobacter pylori infections. Rev Infect Dis. 1990;12 (Suppl 1):S99–106. doi: 10.1093/clinids/12.supplement_1.s99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ernst PB, Gold BD. The disease spectrum of Helicobacter pylori: the immunopathogenesis of gastroduodenal ulcer and gastric cancer. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2000;54:615–40. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.54.1.615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blaser MJ. Helicobacter pylori and gastric diseases. BMJ. 1998;316:1507–10. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7143.1507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Parsonnet J, Hansen S, Rodriguez L, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection and gastric lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:1267–71. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199405053301803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blaser MJ, Chyou PH, Nomura A. Age at establishment of Helicobacter pylori infection and gastric carcinoma, gastric ulcer, and duodenal ulcer risk. Cancer Res. 1995;55:562–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Epidemiology of, and risk factors for, Helicobacter pylori infection among 3194 asymptomatic subjects in 17 populations. The EUROGAST Study Group. Gut. 1993;34:1672–6. doi: 10.1136/gut.34.12.1672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Health Organization. [Accessed on 12/13/2007];Cancer Fact Sheet. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs297/en/

- 15.Asaka M, Kudo M, Kato M, Sugiyama T, Takeda H. Review article: Long-term Helicobacter pylori infection--from gastritis to gastric cancer. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1998;12 (Suppl 1):9–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.1998.00007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Candelli M, Nista EC, Carloni E, et al. Treatment of H. pylori infection: a review. Curr Med Chem. 2005;12:375–84. doi: 10.2174/0929867053363027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.NIH Consensus Conference. Helicobacter pylori in peptic ulcer disease. NIH Consensus Development Panel on Helicobacter pylori in Peptic Ulcer Disease. JAMA. 1994;272:65–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Current European concepts in the management of Helicobacter pylori infection. The Maastricht Consensus Report. European Helicobacter Pylori Study Group. Gut. 1997;41:8–13. doi: 10.1136/gut.41.1.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, O’Morain C, et al. Current concepts in the management of Helicobacter pylori infection--the Maastricht 2–2000 Consensus Report. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16:167–80. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2002.01169.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, O’Morain C, et al. Current concepts in the management of Helicobacter pylori infection: the Maastricht III Consensus Report. Gut. 2007;56:772–81. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.101634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cianci R, Montalto M, Pandolfi F, Gasbarrini GB, Cammarota G. Third-line rescue therapy for Helicobacter pylori infection. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:2313–9. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i15.2313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Versalovic J, Shortridge D, Kibler K, et al. Mutations in 23S rRNA are associated with clarithromycin resistance in Helicobacter pylori. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:477–80. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.2.477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Menninger JR. Functional consequences of binding macrolides to ribosomes. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1985;16 (Suppl A):23–34. doi: 10.1093/jac/16.suppl_a.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Debets-Ossenkopp YJ, Sparrius M, Kusters JG, Kolkman JJ, Vandenbroucke-Grauls CM. Mechanism of clarithromycin resistance in clinical isolates of Helicobacter pylori. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1996;142:37–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1996.tb08404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vester B, Garrett RA. A plasmid-coded and site-directed mutation in Escherichia coli 23S RNA that confers resistance to erythromycin: implications for the mechanism of action of erythromycin. Biochimie. 1987;69:891–900. doi: 10.1016/0300-9084(87)90217-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nash KA, Inderlied CB. Genetic basis of macrolide resistance in Mycobacterium avium isolated from patients with disseminated disease. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:2625–30. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.12.2625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Taylor DE, Ge Z, Purych D, Lo T, Hiratsuka K. Cloning and sequence analysis of two copies of a 23S rRNA gene from Helicobacter pylori and association of clarithromycin resistance with 23S rRNA mutations. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:2621–8. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.12.2621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Versalovic J, Osato MS, Spakovsky K, et al. Point mutations in the 23S rRNA gene of Helicobacter pylori associated with different levels of clarithromycin resistance. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1997;40:283–6. doi: 10.1093/jac/40.2.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hulten K, Gibreel A, Skold O, Engstrand L. Macrolide resistance in Helicobacter pylori: mechanism and stability in strains from clarithromycin-treated patients. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:2550–3. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.11.2550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Umegaki N, Shimoyama T, Nishiya D, Suto T, Fukuda S, Munakata A. Clarithromycin-resistance and point mutations in the 23S rRNA gene in Helicobacter pylori isolates from Japan. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2000;15:906–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2000.02072.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Occhialini A, Urdaci M, Doucet-Populaire F, Bebear CM, Lamouliatte H, Megraud F. Macrolide resistance in Helicobacter pylori: rapid detection of point mutations and assays of macrolide binding to ribosomes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:2724–8. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.12.2724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang G, Taylor DE. Site-specific mutations in the 23S rRNA gene of Helicobacter pylori confer two types of resistance to macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin B antibiotics. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:1952–8. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.8.1952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stone GG, Shortridge D, Flamm RK, et al. Identification of a 23S rRNA gene mutation in clarithromycin-resistant Helicobacter pylori. Helicobacter. 1996;1:227–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.1996.tb00043.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ribeiro ML, Vitiello L, Miranda MC, et al. Mutations in the 23S rRNA gene are associated with clarithromycin resistance in Helicobacter pylori isolates in Brazil. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2003;2:11. doi: 10.1186/1476-0711-2-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Raymond J, Burucoa C, Pietrini O, et al. Clarithromycin resistance in Helicobacter pylori strains isolated from French children: prevalence of the different mutations and coexistence of clones harboring two different mutations in the same biopsy. Helicobacter. 2007;12:157–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2007.00486.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Alarcon T, Vega AE, Domingo D, Martinez MJ, Lopez-Brea M. Clarithromycin resistance among Helicobacter pylori strains isolated from children: prevalence and study of mechanism of resistance by PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:486–99. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.1.486-488.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Khan R, Nahar S, Sultana J, Ahmad MM, Rahman M. T2182C mutation in 23S rRNA is associated with clarithromycin resistance in Helicobacter pylori isolates obtained in Bangladesh. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48:3567–9. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.9.3567-3569.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Toracchio S, Aceto GM, Mariani-Costantini R, Battista P, Marzio L. Identification of a novel mutation affecting domain V of the 23S rRNA gene in Helicobacter pylori. Helicobacter. 2004;9:396–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1083-4389.2004.00267.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hao Q, Li Y, Zhang ZJ, Liu Y, Gao H. New mutation points in 23S rRNA gene associated with Helicobacter pylori resistance to clarithromycin in northeast China. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:1075–7. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v10.i7.1075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Burucoa C, Landron C, Garnier M, Fauchere JL. T2182C mutation is not associated with clarithromycin resistance in Helicobacter pylori. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49:868. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.2.868-870.2005. author reply –70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Garrido L, Toledo H. Novel genotypes in Helicobacter pylori involving domain V of the 23S rRNA gene. Helicobacter. 2007;12:505–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2007.00506.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fontana C, Favaro M, Minelli S, et al. New site of modification of 23S rRNA associated with clarithromycin resistance of Helicobacter pylori clinical isolates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2002;46:3765–9. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.12.3765-3769.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Arthur M, Brisson-Noel A, Courvalin P. Origin and evolution of genes specifying resistance to macrolide, lincosamide and streptogramin antibiotics: data and hypotheses. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1987;20:783–802. doi: 10.1093/jac/20.6.783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Meier A, Kirschner P, Springer B, et al. Identification of mutations in 23S rRNA gene of clarithromycin-resistant Mycobacterium intracellulare. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;38:381–4. doi: 10.1128/aac.38.2.381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kutschke A, de Jonge BL. Compound efflux in Helicobacter pylori. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49:3009–10. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.7.3009-3010.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Paul TR, Halligan NG, Blaszczak LC, Parr TR, Jr, Beveridge TJ. A new mercury-penicillin V derivative as a probe for ultrastructural localization of penicillin-binding proteins in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:4689–700. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.14.4689-4700.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Georgopapadakou NH. Penicillin-binding proteins and bacterial resistance to beta-lactams. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37:2045–53. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.10.2045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Blumberg PM, Strominger JL. Interaction of penicillin with the bacterial cell: penicillin-binding proteins and penicillin-sensitive enzymes. Bacteriol Rev. 1974;38:291–335. doi: 10.1128/br.38.3.291-335.1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.van Zwet AA, Vandenbroucke-Grauls CM, Thijs JC, van der Wouden EJ, Gerrits MM, Kusters JG. Stable amoxicillin resistance in Helicobacter pylori. Lancet. 1998;352:1595. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)00064-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Glupczynski Y, Megraud F, Lopez-Brea M, Andersen LP. European multicentre survey of in vitro antimicrobial resistance in Helicobacter pylori. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2001;20:820–3. doi: 10.1007/s100960100611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mendonca S, Ecclissato C, Sartori MS, et al. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori resistance to metronidazole, clarithromycin, amoxicillin, tetracycline, and furazolidone in Brazil. Helicobacter. 2000;5:79–83. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5378.2000.00011.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rafeey M, Ghotaslou R, Nikvash S, Hafez AA. Primary resistance in Helicobacter pylori isolated in children from Iran. J Infect Chemother. 2007;13:291–5. doi: 10.1007/s10156-007-0543-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kalach N, Serhal L, Asmar E, et al. Helicobacter pylori primary resistant strains over 11 years in French children. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2007;59:217–22. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2007.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Godoy AP, Reis FC, Ferraz LF, et al. Differentially expressed genes in response to amoxicillin in Helicobacter pylori analyzed by RNA arbitrarily primed PCR. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2007;50:226–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2006.00209.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dore MP, Graham DY, Sepulveda AR. Different penicillin-binding protein profiles in amoxicillin-resistant Helicobacter pylori. Helicobacter. 1999;4:154–61. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5378.1999.99310.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Krishnamurthy P, Parlow MH, Schneider J, et al. Identification of a novel penicillin-binding protein from Helicobacter pylori. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:5107–10. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.16.5107-5110.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Okamoto T, Yoshiyama H, Nakazawa T, et al. A change in PBP1 is involved in amoxicillin resistance of clinical isolates of Helicobacter pylori. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2002;50:849–56. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkf140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gerrits MM, Schuijffel D, van Zwet AA, Kuipers EJ, Vandenbroucke-Grauls CM, Kusters JG. Alterations in penicillin-binding protein 1A confer resistance to beta-lactam antibiotics in Helicobacter pylori. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2002;46:2229–33. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.7.2229-2233.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kwon DH, Dore MP, Kim JJ, et al. High-level beta-lactam resistance associated with acquired multidrug resistance in Helicobacter pylori. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003;47:2169–78. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.7.2169-2178.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Co EM, Schiller NL. Resistance mechanisms in an in vitro-selected amoxicillin-resistant strain of Helicobacter pylori. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006;50:4174–6. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00759-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.DeLoney CR, Schiller NL. Characterization of an In vitro-selected amoxicillin-resistant strain of Helicobacter pylori. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:3368–73. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.12.3368-3373.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Harris AG, Hazell SL, Netting AG. Use of digoxigenin-labelled ampicillin in the identification of penicillin-binding proteins in Helicobacter pylori. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2000;45:591–8. doi: 10.1093/jac/45.5.591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rimbara E, Noguchi N, Kawai T, Sasatsu M. Correlation between substitutions in penicillin-binding protein 1 and amoxicillin resistance in Helicobacter pylori. Microbiol Immunol. 2007;51:939–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2007.tb03990.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Matteo MJ, Granados G, Olmos M, Wonaga A, Catalano M. Helicobacter pylori amoxicillin heteroresistance due to point mutations in PBP-1A in isogenic isolates. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2008;61:474–7. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkm504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rimbara E, Noguchi N, Kawai T, Sasatsu M. Mutations in penicillin-binding proteins 1, 2 and 3 are responsible for amoxicillin resistance in Helicobacter pylori. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2008;61:995–8. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkn051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ings RM, McFadzean JA, Ormerod WE. The mode of action of metronidazole in Trichomonas vaginalis and other micro-organisms. Biochem Pharmacol. 1974;23:1421–9. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(74)90362-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.O’Brien RW, Morris JG. Effect of metronidazole on hydrogen production by Clostridium acetobutylicum. Arch Mikrobiol. 1972;84:225–33. doi: 10.1007/BF00425200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zullo A, Perna F, Hassan C, et al. Primary antibiotic resistance in Helicobacter pylori strains isolated in northern and central Italy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;25:1429–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03331.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hu CT, Wu CC, Lin CY, et al. Resistance rate to antibiotics of Helicobacter pylori isolates in eastern Taiwan. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;22:720–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2006.04743.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kumala W, Rani A. Patterns of Helicobacter pylori isolate resistance to fluoroquinolones, amoxicillin, clarithromycin and metronidazoles. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2006;37:970–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Moore RA, Beckthold B, Bryan LE. Metronidazole uptake in Helicobacter pylori. Can J Microbiol. 1995;41:746–9. doi: 10.1139/m95-102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chang KC, Ho SW, Yang JC, Wang JT. Isolation of a genetic locus associated with metronidazole resistance in Helicobacter pylori. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;236:785–8. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Debets-Ossenkopp YJ, Pot RG, van Westerloo DJ, et al. Insertion of mini-IS605 and deletion of adjacent sequences in the nitroreductase (rdxA) gene cause metronidazole resistance in Helicobacter pylori NCTC11637. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:2657–62. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.11.2657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Jorgensen MA, Manos J, Mendz GL, Hazell SL. The mode of action of metronidazole in Helicobacter pylori: futile cycling or reduction? J Antimicrob Chemother. 1998;41:67–75. doi: 10.1093/jac/41.1.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Goodwin A, Kersulyte D, Sisson G, Veldhuyzen van Zanten SJ, Berg DE, Hoffman PS. Metronidazole resistance in Helicobacter pylori is due to null mutations in a gene (rdxA) that encodes an oxygen-insensitive NADPH nitroreductase. Mol Microbiol. 1998;28:383–93. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00806.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Tankovic J, Lamarque D, Delchier JC, Soussy CJ, Labigne A, Jenks PJ. Frequent association between alteration of the rdxA gene and metronidazole resistance in French and North African isolates of Helicobacter pylori. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:608–13. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.3.608-613.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Jorgensen MA, Trend MA, Hazell SL, Mendz GL. Potential involvement of several nitroreductases in metronidazole resistance in Helicobacter pylori. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2001;392:180–91. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2001.2427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Bereswill S, Krainick C, Stahler F, Herrmann L, Kist M. Analysis of the rdxA gene in high-level metronidazole-resistant clinical isolates confirms a limited use of rdxA mutations as a marker for prediction of metronidazole resistance in Helicobacter pylori. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2003;36:193–8. doi: 10.1016/S0928-8244(03)00031-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Jenks PJ, Ferrero RL, Labigne A. The role of the rdxA gene in the evolution of metronidazole resistance in Helicobacter pylori. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1999;43:753–8. doi: 10.1093/jac/43.6.753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kwon DH, Pena JA, Osato MS, Fox JG, Graham DY, Versalovic J. Frameshift mutations in rdxA and metronidazole resistance in North American Helicobacter pylori isolates. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2000;46:793–6. doi: 10.1093/jac/46.5.793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Solca NM, Bernasconi MV, Piffaretti JC. Mechanism of metronidazole resistance in Helicobacter pylori: comparison of the rdxA gene sequences in 30 strains. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:2207–10. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.8.2207-2210.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Chisholm SA, Owen RJ. Mutations in Helicobacter pylori rdxA gene sequences may not contribute to metronidazole resistance. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2003;51:995–9. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkg192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kwon DH, El-Zaatari FA, Kato M, et al. Analysis of rdxA and involvement of additional genes encoding NAD(P)H flavin oxidoreductase (FrxA) and ferredoxin-like protein (FdxB) in metronidazole resistance of Helicobacter pylori. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:2133–42. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.8.2133-2142.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kwon DH, Kato M, El-Zaatari FA, Osato MS, Graham DY. Frame-shift mutations in NAD(P)H flavin oxidoreductase encoding gene (frxA) from metronidazole resistant Helicobacter pylori ATCC43504 and its involvement in metronidazole resistance. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2000;188:197–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2000.tb09193.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kwon DH, Hulten K, Kato M, et al. DNA sequence analysis of rdxA and frxA from 12 pairs of metronidazole-sensitive and -resistant clinical Helicobacter pylori isolates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2001;45:2609–15. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.9.2609-2615.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Jeong JY, Berg DE. Mouse-colonizing Helicobacter pylori SS1 is unusually susceptible to metronidazole due to two complementary reductase activities. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:3127–32. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.11.3127-3132.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Jeong JY, Mukhopadhyay AK, Akada JK, Dailidiene D, Hoffman PS, Berg DE. Roles of FrxA and RdxA nitroreductases of Helicobacter pylori in susceptibility and resistance to metronidazole. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:5155–62. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.17.5155-5162.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Yang YJ, Wu JJ, Sheu BS, Kao AW, Huang AH. The rdxA gene plays a more major role than frxA gene mutation in high-level metronidazole resistance of Helicobacter pylori in Taiwan. Helicobacter. 2004;9:400–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1083-4389.2004.00270.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Chisholm SA, Owen RJ. Frameshift mutations in frxA occur frequently and do not provide a reliable marker for metronidazole resistance in UK isolates of Helicobacter pylori. J Med Microbiol. 2004;53:135–40. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.05342-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Marais A, Bilardi C, Cantet F, Mendz GL, Megraud F. Characterization of the genes rdxA and frxA involved in metronidazole resistance in Helicobacter pylori. Res Microbiol. 2003;154:137–44. doi: 10.1016/S0923-2508(03)00030-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Trend MA, Jorgensen MA, Hazell SL, Mendz GL. Oxidases and reductases are involved in metronidazole sensitivity in Helicobacter pylori. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2001;33:143–53. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(00)00085-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.McAtee CP, Hoffman PS, Berg DE. Identification of differentially regulated proteins in metronidozole resistant Helicobacter pylori by proteome techniques. Proteomics. 2001;1:516–21. doi: 10.1002/1615-9861(200104)1:4<516::AID-PROT516>3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Leitsch D, Kolarich D, Wilson IB, Altmann F, Duchene M. Nitroimidazole action in Entamoeba histolytica: a central role for thioredoxin reductase. PLoS Biol. 2007;5:e211. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Baker LM, Raudonikiene A, Hoffman PS, Poole LB. Essential thioredoxin-dependent peroxiredoxin system from Helicobacter pylori: genetic and kinetic characterization. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:1961–73. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.6.1961-1973.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.van Amsterdam K, Bart A, van der Ende A. A Helicobacter pylori TolC efflux pump confers resistance to metronidazole. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49:1477–82. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.4.1477-1482.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Chopra I, Roberts M. Tetracycline antibiotics: mode of action, applications, molecular biology, and epidemiology of bacterial resistance. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2001;65:232–60. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.65.2.232-260.2001. second page, table of contents. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Chopra I, Hawkey PM, Hinton M. Tetracyclines, molecular and clinical aspects. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1992;29:245–77. doi: 10.1093/jac/29.3.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Schnappinger D, Hillen W. Tetracyclines: antibiotic action, uptake, and resistance mechanisms. Arch Microbiol. 1996;165:359–69. doi: 10.1007/s002030050339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Lawson AJ, Elviss NC, Owen RJ. Real-time PCR detection and frequency of 16S rDNA mutations associated with resistance and reduced susceptibility to tetracycline in Helicobacter pylori from England and Wales. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2005;56:282–6. doi: 10.1093/jac/dki199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Kwon DH, Kim JJ, Lee M, et al. Isolation and characterization of tetracycline-resistant clinical isolates of Helicobacter pylori. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:3203–5. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.11.3203-3205.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Wu H, Shi XD, Wang HT, Liu JX. Resistance of Helicobacter pylori to metronidazole, tetracycline and amoxycillin. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2000;46:121–3. doi: 10.1093/jac/46.1.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Midolo PD, Korman MG, Turnidge JD, Lambert JR. Helicobacter pylori resistance to tetracycline. Lancet. 1996;347:1194–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Gerrits MM, de Zoete MR, Arents NL, Kuipers EJ, Kusters JG. 16S rRNA mutation-mediated tetracycline resistance in Helicobacter pylori. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2002;46:2996–3000. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.9.2996-3000.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Trieber CA, Taylor DE. Mutations in the 16S rRNA genes of Helicobacter pylori mediate resistance to tetracycline. J Bacteriol. 2002;184:2131–40. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.8.2131-2140.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Nonaka L, Connell SR, Taylor DE. 16S rRNA mutations that confer tetracycline resistance in Helicobacter pylori decrease drug binding in Escherichia coli ribosomes. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:3708–12. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.11.3708-3712.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Gerrits MM, Berning M, Van Vliet AH, Kuipers EJ, Kusters JG. Effects of 16S rRNA gene mutations on tetracycline resistance in Helicobacter pylori. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003;47:2984–6. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.9.2984-2986.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Ribeiro ML, Gerrits MM, Benvengo YH, et al. Detection of high-level tetracycline resistance in clinical isolates of Helicobacter pylori using PCR-RFLP. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2004;40:57–61. doi: 10.1016/S0928-8244(03)00277-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Wu JY, Kim JJ, Reddy R, Wang WM, Graham DY, Kwon DH. Tetracycline-resistant clinical Helicobacter pylori isolates with and without mutations in 16S rRNA-encoding genes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49:578–83. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.2.578-583.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Dailidiene D, Bertoli MT, Miciuleviciene J, et al. Emergence of tetracycline resistance in Helicobacter pylori: multiple mutational changes in 16S ribosomal DNA and other genetic loci. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2002;46:3940–6. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.12.3940-3946.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Bina JE, Nano F, Hancock RE. Utilization of alkaline phosphatase fusions to identify secreted proteins, including potential efflux proteins and virulence factors from Helicobacter pylori. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1997;148:63–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1997.tb10268.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Bina JE, Alm RA, Uria-Nickelsen M, Thomas SR, Trust TJ, Hancock RE. Helicobacter pylori uptake and efflux: basis for intrinsic susceptibility to antibiotics in vitro. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:248–54. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.2.248-254.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Smith JT. Mechanism of action of quinolones. Infection. 1986;14 (Suppl 1):S3–15. doi: 10.1007/BF01645191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Cullen ME, Wyke AW, Kuroda R, Fisher LM. Cloning and characterization of a DNA gyrase A gene from Escherichia coli that confers clinical resistance to 4-quinolones. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1989;33:886–94. doi: 10.1128/aac.33.6.886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Yoshida H, Bogaki M, Nakamura M, Nakamura S. Quinolone resistance-determining region in the DNA gyrase gyrA gene of Escherichia coli. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1990;34:1271–2. doi: 10.1128/aac.34.6.1271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Cabrita J, Oleastro M, Matos R, et al. Features and trends in Helicobacter pylori antibiotic resistance in Lisbon area, Portugal (1990–1999) J Antimicrob Chemother. 2000;46:1029–31. doi: 10.1093/jac/46.6.1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Kim JM, Kim JS, Kim N, Jung HC, Song IS. Distribution of fluoroquinolone MICs in Helicobacter pylori strains from Korean patients. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2005;56:965–7. doi: 10.1093/jac/dki334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Wang G, Wilson TJ, Jiang Q, Taylor DE. Spontaneous mutations that confer antibiotic resistance in Helicobacter pylori. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2001;45:727–33. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.3.727-733.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Moore RA, Beckthold B, Wong S, Kureishi A, Bryan LE. Nucleotide sequence of the gyrA gene and characterization of ciprofloxacin-resistant mutants of Helicobacter pylori. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:107–11. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.1.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Tankovic J, Lascols C, Sculo Q, Petit JC, Soussy CJ. Single and double mutations in gyrA but not in gyrB are associated with low- and high-level fluoroquinolone resistance in Helicobacter pylori. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003;47:3942–4. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.12.3942-3944.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Miyachi H, Miki I, Aoyama N, et al. Primary levofloxacin resistance and gyrA/B mutations among Helicobacter pylori in Japan. Helicobacter. 2006;11:243–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2006.00415.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Nishizawa T, Suzuki H, Kurabayashi K, et al. Gatifloxacin resistance and mutations in gyrA after unsuccessful Helicobacter pylori eradication in Japan. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006;50:1538–40. doi: 10.1128/AAC.50.4.1538-1540.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Tomb JF, White O, Kerlavage AR, et al. The complete genome sequence of the gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Nature. 1997;388:539–47. doi: 10.1038/41483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Alm RA, Ling LS, Moir DT, et al. Genomic-sequence comparison of two unrelated isolates of the human gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Nature. 1999;397:176–80. doi: 10.1038/16495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Calvori C, Frontali L, Leoni L, Tecce G. Effect of rifamycin on protein synthesis. Nature. 1965;207:417–8. doi: 10.1038/207417a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Jin DJ, Gross CA. Mapping and sequencing of mutations in the Escherichia coli rpoB gene that lead to rifampicin resistance. J Mol Biol. 1988;202:45–58. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(88)90517-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Heep M, Beck D, Bayerdorffer E, Lehn N. Rifampin and rifabutin resistance mechanism in Helicobacter pylori. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:1497–9. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.6.1497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Glocker E, Bogdan C, Kist M. Characterization of rifampicin-resistant clinical Helicobacter pylori isolates from Germany. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2007;59:874–9. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkm039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Heep M, Rieger U, Beck D, Lehn N. Mutations in the beginning of the rpoB gene can induce resistance to rifamycins in both Helicobacter pylori and Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:1075–7. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.4.1075-1077.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Heep M, Odenbreit S, Beck D, et al. Mutations at four distinct regions of the rpoB gene can reduce the susceptibility of Helicobacter pylori to rifamycins. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:1713–5. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.6.1713-1715.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Jenks PJ, Ferrero RL, Tankovic J, Thiberge JM, Labigne A. Evaluation of nitrofurantoin combination therapy of metronidazole-sensitive and -resistant Helicobacter pylori infections in mice. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:2623–9. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.10.2623-2629.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Whiteway J, Koziarz P, Veall J, et al. Oxygen-insensitive nitroreductases: analysis of the roles of nfsA and nfsB in development of resistance to 5-nitrofuran derivatives in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:5529–39. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.21.5529-5539.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.McOsker CC, Fitzpatrick PM. Nitrofurantoin: mechanism of action and implications for resistance development in common uropathogens. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1994;33 (Suppl A):23–30. doi: 10.1093/jac/33.suppl_a.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Kwon DH, Lee M, Kim JJ, et al. Furazolidone- and nitrofurantoin-resistant Helicobacter pylori: prevalence and role of genes involved in metronidazole resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2001;45:306–8. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.1.306-308.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Haas CE, Nix DE, Schentag JJ. In vitro selection of resistant Helicobacter pylori. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1990;34:1637–41. doi: 10.1128/aac.34.9.1637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Sisson G, Goodwin A, Raudonikiene A, et al. Enzymes associated with reductive activation and action of nitazoxanide, nitrofurans, and metronidazole in Helicobacter pylori. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2002;46:2116–23. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.7.2116-2123.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Block G, Patterson B, Subar A. Fruit, vegetables, and cancer prevention: a review of the epidemiological evidence. Nutr Cancer. 1992;18:1–29. doi: 10.1080/01635589209514201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Steinmetz KA, Potter JD. Vegetables, fruit, and cancer. I. Epidemiology. Cancer Causes Control. 1991;2:325–57. doi: 10.1007/BF00051672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Zhang ZW, Patchett SE, Perrett D, Katelaris PH, Domizio P, Farthing MJ. The relation between gastric vitamin C concentrations, mucosal histology, and CagA seropositivity in the human stomach. Gut. 1998;43:322–6. doi: 10.1136/gut.43.3.322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Wang X, Willen R, Wadstrom T. Astaxanthin-rich algal meal and vitamin C inhibit Helicobacter pylori infection in BALB/cA mice. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:2452–7. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.9.2452-2457.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Zhang HM, Wakisaka N, Maeda O, Yamamoto T. Vitamin C inhibits the growth of a bacterial risk factor for gastric carcinoma: Helicobacter pylori. Cancer. 1997;80:1897–903. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Johansson C, Aly A, Befrits R, Smedfors B, Uribe A. Protection of the gastroduodenal mucosa by prostaglandins. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1985;110:41–8. doi: 10.3109/00365528509095830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Tarnawski A, Hollander D, Stachura J, Krause WJ. Arachidonic acid protection of gastric mucosa against alcohol injury: sequential analysis of morphologic and functional changes. J Lab Clin Med. 1983;102:340–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Hollander D, Tarnawski A, Ivey KJ, et al. Arachidonic acid protection of rat gastric mucosa against ethanol injury. J Lab Clin Med. 1982;100:296–308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Skene C, Young A, Every A, Sutton P. Helicobacter pylori flagella: antigenic profile and protective immunity. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2007;50:249–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2007.00263.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Morihara F, Fujii R, Hifumi E, Nishizono A, Uda T. Effects of vaccination by a recombinant antigen ureB138 (a segment of the beta-subunit of urease) against Helicobacter pylori infection. J Med Microbiol. 2007;56:847–53. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.47061-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Zhao W, Wu W, Xu X. Oral vaccination with liposome-encapsulated recombinant fusion peptide of urease B epitope and cholera toxin B subunit affords prophylactic and therapeutic effects against H. pylori infection in BALB/c mice. Vaccine. 2007;25:7664–73. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.08.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Raghavan S, Hjulstrom M, Holmgren J, Svennerholm AM. Protection against experimental Helicobacter pylori infection after immunization with inactivated H. pylori whole-cell vaccines. Infect Immun. 2002;70:6383–8. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.11.6383-6388.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Ferrero RL, Thiberge JM, Kansau I, Wuscher N, Huerre M, Labigne A. The GroES homolog of Helicobacter pylori confers protective immunity against mucosal infection in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:6499–503. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.14.6499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Sutton P, Doidge C, Pinczower G, et al. Effectiveness of vaccination with recombinant HpaA from Helicobacter pylori is influenced by host genetic background. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2007;50:213–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2006.00206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Fowler M, Thomas RJ, Atherton J, Roberts IS, High NJ. Galectin-3 binds to Helicobacter pylori O-antigen: it is upregulated and rapidly secreted by gastric epithelial cells in response to H. pylori adhesion. Cell Microbiol. 2006;8:44–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2005.00599.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Satin B, Del Giudice G, Della Bianca V, et al. The neutrophil-activating protein (HP-NAP) of Helicobacter pylori is a protective antigen and a major virulence factor. J Exp Med. 2000;191:1467–76. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.9.1467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]