Abstract

We previously reported the formulation and physical properties of HER2 (Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2)-specific Affibody (ZHER2:342-Cys) conjugated thermosensitive liposomes (HER2+ Affisomes). Here we examined localized delivery potential of these Affisomes by monitoring cellular interactions, intracellular uptake, and hyperthermia-induced effects on drug delivery. We modified ZHER2:342-Cys by introducing a glycine-serine spacer before the C-terminus cysteine (called ZHER2-GS-Cys) to achieve accessibility to cell-surface expressed HER2. This modification did not affect HER2-specific binding and ZHER2-GS-Cys retained its ability to conjugate to the liposomes containing dipalmitoyl phosphatidyl choline: DSPE-PEG2000-Malemide, 96:04 mole ratios (HER2+ Affisomes). HER2+ Affisomes were either (i) fluorescently labeled with rhodamine-PE and calcein or (ii) loaded with an anticancer drug Doxorubicin (DOX). Fluorescently labeled HER2+ Affisomes showed at least 10 fold increase in binding to HER2+ cells (SK-BR-3) when compared to HER2− cells (MDA-MB-468) at 37°C. A competition experiment using free ZHER2-GS-Cys blocked HER2+ Affisomes-SK-BR-3 cell associations. Imaging with confocal microscopy showed that HER2+ Affisomes accumulated in the cytosol of SK-BR-3 cells at 37°C. Hyperthermia-induced intracellular release experiments showed that the treatment of HER2+ Affisome/SK-BR-3 cell complexes with a 45°C (±1°C) pre-equilibrated buffer resulted in cytosolic delivery of calcein. Substantial calcein release was observed within 20 minutes at 45°C, with no effect on cell viability under these conditions. Similarly, DOX-loaded HER2+ Affisomes showed at least 2–3 fold higher accumulation of DOX in SK-BR-3 cells as compared to control liposomes. DOX-mediated cytotoxicity was more pronounced in SK-BR-3 cells especially at lower doses of HER2+ Affisomes. Brief exposure of liposome-cell complexes at 45°C prior to the onset of incubations for cell killing assays resulted in enhanced cytotoxicity for Affisomes and control liposomes. However, Doxil (a commercially available liposome formulation) showed significantly lower toxicity under identical conditions. Therefore, our data demonstrate that HER2+ Affisomes encompass both targeting and triggering potential and hence may prove to be viable nano drug delivery carriers for breast cancer treatment.

Keywords: Drug delivery, triggerable liposomes, targeting, affibody, hyperthermia

1. Introduction

Liposomes primarily consist of phospholipids (the major components of biological membranes) and are amongst the longest-studied nano drug delivery carriers (DDC). To date, a number of formulations are used in the clinic while others await clinical trials. Two important features, namely targeting potential and on-demand drug release properties (triggering) of liposomes are important considerations to enhance their utility in the clinic. It is apparent that the use of targeted liposomes will result in an increased intracellular accumulation, provided the ligands (attached to the liposome surface) will initiate receptor internalization. However, effective release of contents from these liposomes (once they have accumulated in the targeted cells) is a prerequisite for improved drug delivery. In this study we have attempted to achieve this goal by designing thermosensitive liposomes bearing a Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2 (HER2)-specific ligand to target breast cancer. Here we have combined the well-documented thermosensitive liposome formulations with a HER2-specific Affibody-based targeting agent (described below). We propose that such targeted-triggerable liposomes (TTL) are likely to be ideal DDC for cancer treatment.

Externally triggerable liposomes either utilize the principle of local hyperthermia [1] or rely on the application of light-sensitive lipid molecules [2]. Among these, thermosensitive liposomes are the best-studied example of localized drug release, and are based on the lipid destabilizing mechanism(s), phase transition effects, and thermal melting temperatures (Tm)[3]. Hyperthermia can be used to selectively enhance both the delivery and the rate of release of drugs from liposomes to targeted tissues [1,4]. In this system, a rapid and efficient release of the liposome-entrapped drugs occurs by locally raising the temperature a few degrees above the human body temperature [5]. Although thermosensitive liposomes, first described in late 1970’s by Yatvin et al [3], are currently in Phase 3 clinical trials, these nanoparticles were not designed for receptor-mediated targeting, until a recent study by Negussie and colleagues [6].

Ligands such as antibodies, peptides and vitamins (example, folic acid), which can bind to upregulated/overexpressed receptors on tumor tissues have been investigated for their use in targeted drug delivery [7]. Antibody-coated liposomes (immunoliposomes) have been extensively studied [8,9], although their future in the clinic remains to be seen. An important consideration for ligand-based DDC is the availability of technology for large scale production of the ligands and issues related to their stability [7]. Recently, we [10] as well as others [11,12] have investigated Affibody molecules as alternatives to antibodies for nano-particulate drug delivery. Affibody® affinity ligands are innovative protein-engineering technologies. They are small (6–9kDa), simple proteins composed of a three-helix bundle based on the scaffold of one of the IgG-binding domains of Protein A. This scaffold has excellent features as an affinity ligand and can be designed to bind with high affinity to any given target protein. Affibody molecules offer advantages as being extremely stable and highly soluble α-helical proteins, which can be readily expressed in bacterial systems or produced by peptide synthesis [13].

HER2 is noted for its role in the pathogenesis of various types of malignancies including breast, lung, prostate, and ovarian carcinomas. Because there is no known natural ligand to HER2 and its expression in normal tissues is minimal, this receptor presents a suitable target for therapy. For targeting thermosensitive liposomes to treat breast cancer, we initially used ZHER2:342-Cys Affibody molecule, which binds to HER2 with high affinity (22 pM) and features a C-terminus cysteine that is available for conjugation via a maleimide-sulfhydryl reaction [14]. Our HER2-specific Affibody-conjugated liposomes (HER2+ Affisomes) retained their thermosensitivity without any significant modulation in their physico-chemical characteristics [10]. However, these HER2+ Affisomes showed limited specific interactions with HER2-expressing cells (unpublished observations). Highly specific association of monomeric Affibody molecules to HER2 on the surface of cells is well documented [13]. Since ZHER2:342-Cys was coupled to the surface of liposomes via a pegylated lipid, we reasoned that limited interaction of liposome-conjugated Affibody was due to either steric constraints or altered spatial distribution in the liposome bilayer. Therefore, we introduced a spacer at the c-terminus of the Affibody molecule to decrease these constraints and enhance access to HER2 expressed on target cells.

In the present study, we have designed a modified HER2-specific Affibody molecule that includes a glycine-serine linker between the main Affibody segment and its C-terminus cysteine (“ZHER2-GS-Cys”) (Figure 1). Using megaprimer PCR cloning technology, we have successfully produced ZHER2-GS-Cys that retains its binding ability to cell surface-expressed HER2. Our observations that HER2+ Affisomes accumulate in HER2+ cells, subsequently release their contents intracellularly, and demonstrate improved cytotoxicity at temperatures above 37°C renders them attractive TTL using the local hyperthermia approach. Our newly designed HER2+ Affisome formulations may have implications in treatment of HER2 positive tumors, including breast cancer.

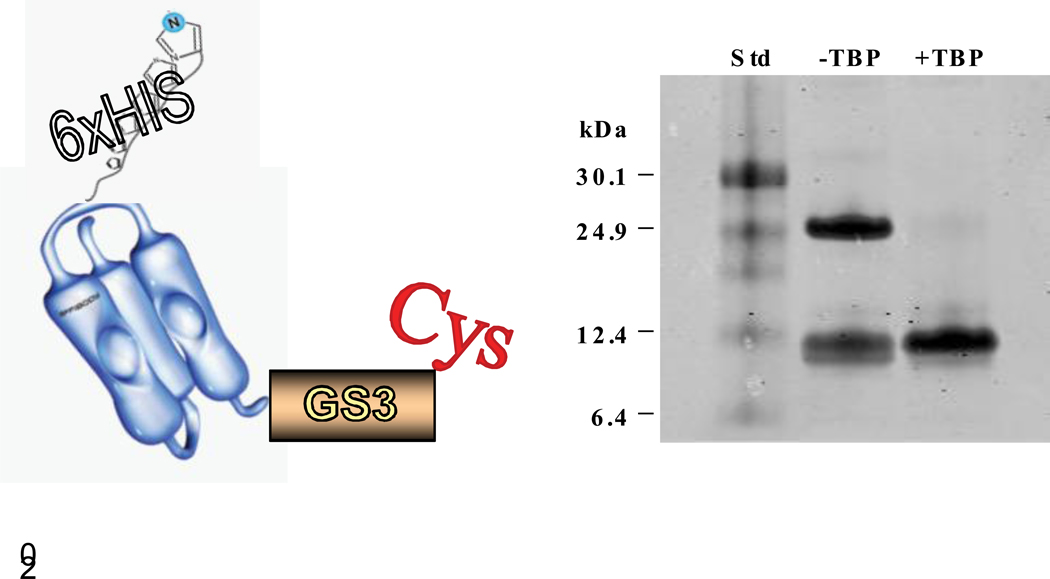

Figure 1. Construction and characterization of ZHER2-GS-Cys.

A) Design of ZHER2-GS-Cys includes introduction of a spacer (glycine-serine linker) at the C-terminus before cysteine residue. The N-terminus also includes a histidine tag (6× His)

B) ZHER2-GS-Cys was analyzed by gel electrophoresis. Samples were loaded in a 4–12% Bis-Tris gel (NuPage) and allowed to run in MES/SDS running buffer at 200V for 35 minutes under reducing conditions. The gel was stained with Microwave Blue (Protiga, Frederick, MD). The images were scanned using the Odyssey infrared imaging system software (LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE). Left lane: Kaleidoscope Prestained Standards (BioRad, cat# 161–0324). Center lane: ZHER2-GS-Cys shown as a monomer and dimer. Right lane: ZHER2-GS-Cys reduced with TBP

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Materials

Sepharose CL-6B was from GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Piscataway, NJ. Calcein was from Fluka- Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Tributylphosphine (TBP) was from Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA); all other reagents were from Sigma-Aldrich Inc. (St. Louis, MO). Doxorubicin-hydrochloride (DOX-HCl) (Bedford Laboratories, Bedford, OH) and Doxil (Ben Venue Laboratories, Bedford, OH) were obtained through the NIH Pharmacy, Clinical Center, Bethesda, MD. Anti-Affibody IgG (cat#20.1000.01.0005) was from Affibody AB (Bromma, Sweden). Rhodamine-labeled anti-goat IgG was from Abcam (Cambridge, MA; Cat# ab6738). Herceptin (Trastuzumab) is a recombinant humanized mAb (Genentech, Inc., South San Francisco, CA), purchased via the NIH pharmacy (Bethesda, MD).

2.2 Lipids

1,2-Dipalmitoyl-sn-Glycero-3-Phosphocholine (DPPC), 1,2-Distearoyl-sn-Glycero-3-Phosphoethanolamine-N-[Maleimide(Polyethylene Glycol)2000] (DSPE-PEG2000-Maleimide), and 1,2-Dioleoyl-sn-Glycero-3-Phosphoethanolamine-N-(Lissamine Rhodamine B Sulfonyl) (Lissamine Rhodamine PE) were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids, Inc. (Alabaster, AL).

2.3 Cells

HER2 expressing human breast adenocarcinoma cells (SK-BR-3, ATCC HTB-30™) and HER2 negative human breast adenocarcinoma cells (MDA-MB-468, ATCC HTB-132) were purchased from the American type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA). The cells were cultured in McCoy’s 5A medium supplemented with 10% (v/v) heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) and penicillin/streptomycin as antibiotics at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. Other culture reagents were bought from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA).

2.4 Preparation of Modified ZHER2 Affibody molecule (ZHER2-GS-Cys)

Affibody molecules were kindly provided by our CRADA (cooperative research and development agreement) partner in Sweden (Affibody AB, Bromma, Sweden). The details of cloning, expression and binding to the HER2+ expressing cells is provided in supplementary content (Figure 1S).

2.5 Preparation of Affibody-conjugated liposomes

Sonicated liposomes were prepared essentially as described [15]. Our lipid mixtures included DPPC:DSPE-PEG2000-Maleimide:Lissamine Rhodamine PE (96:04:0.1 mole ratio). Details of liposome preparation, calcein or DOX loading, affibody conjugation and characterization of Affisomes are provided in supplementary content (Figure 2S) [16].

2.6 HER2+ Affisome-cell interactions

Cells were plated on either 12-well (105/well) or six-well clusters (3×105/well) 48 hours prior to the binding experiments. HER2+ Affisomes (or control liposomes) were added in culture medium and incubations were continued for various time periods. The exact conditions for specific experiments are given in Figure legends. To determine relative binding of HER2+ Affisomes, we analyzed samples by either fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) or microscopy.

2.6.1 FACS Analysis

Cells were washed with PBS+1%BSA (×2), and lifted with EDTA buffer (Cell Disassociation Buffer, Invitrogen), and centrifuged. Cell pellets were washed with PBS+1%BSA (×2) and resuspended to 2–6×105/ml in PBS+5%FBS.

2.6.2 Fluorescence Microscopy

For initial visualization of Affisome binding, cells were washed with PBS (×2) and imaged for rhodamine or calcein fluorescence with a 20X objective using a NIKON Eclipse TE200 (Melville, NJ) inverted microscope. Images were processed using the Metamorph software (Universal Imaging, Inc) [17]. To assess the intracellular localization of HER2+ Affisomes, cells plated on 35 mm glass bottom dishes (MatTek, Ashland, MA) were incubated with HER2+ Affisomes at 37°C for 1–2 hours. EGFP-Affiprobe, which does not internalize[18], was used as a control in these experiments. Image acquisition and analysis was done essentially as described using a 60× oil immersion objective lens (Olympus PLAPON NA 1.42) and Olympus FV1000 confocal microscope [15].

2.6.3 Competition Assay

Binding specificity was determined as follows. Cells (SK-BR-3) were pre-incubated with 10-fold excess of either HER2-GS-Cys or Herceptin at 4°C for 1 hour. Unbound molecules were removed by washing with PBS+1%BSA, HER2+ Affisomes were added and incubations continued for an additional 1 hour at 4°C. Binding of HER2+ Affisomes was analyzed by FACS using cell associated rhodamine fluorescence.

2.7 Hyperthermia-induced intracellular release of calcein from HER2+ Affisomes

HER2+ Affisomes were incubated with cells as described in Fluorescence Microscopy section above and images were captured. Samples were returned to a CO2 incubator prior to monitoring temperature triggered calcein release. We used 45°C pre-equilibrated PBS and a temperature control device attached to the Olympus FV1000 microscope stage box for hyperthermia induced calcein release experiments. The protocol is depicted in Figure 3S. For the experiments described here, the microscope stage temperature was maintained at 45°C. To initiate intracellular calcein release, buffer from dishes containing the Affisome-cell complexes was replaced with 45°C pre-equilibrated PBS, and images were acquired immediately. While maintaining the stage chamber temperature at 45°C, intermittent time-dependent image acquisitions were done up to 20 minutes. During this experiment, sample temperature was measured to be ±1°C within the desired temperature. Increase in fluorescence following 45°C treatment was also quantitated and is described in supplemental contents.

2.8. Interaction of DOX-loaded HER2+ Affisomes with SK-BR-3 cells

2.8.1 Accumulation of liposomal DOX

SK-BR-3 cells were plated on six-well clusters one day prior to the experiments. The media in the wells was replaced with DOX-loaded Affisomes or control liposomes (= 15 µg DOX per well) in culture medium, and the cells were incubated at 37°C for various time periods. At the end of incubations, cells were washed with PBS containing 1% BSA (×3, 2 ml each) and cells were suspended using the cell dissociation buffer. The cells were pelleted by centrifugation, washed with PBS containing 1% BSA (×2, 0.5 ml each) and the pellets were resuspended in 0.3 ml PBS. Subsequently 30 µl TX100 (10% w/v) was added to each tube and cell lysis was achieved by incubation for 20 minutes at 37°C. The samples were transferred to 96-well plate (0.1 ml per well) and DOX fluorescence was measured as above.

2.8.2 Hyperthermia-induced Cellular Toxicit

SK-BR-3 cells were plated on 48 well clusters (104/well) one day prior to experiments in duplicate. Various doses of control liposomes, Affisomes or Doxil (diluted in culture medium) were added to the wells in a total volume of 0.5 ml per well. The samples were incubated for 1 hour at 37°C, then unbound particles were removed and cells were washed with the medium (×1, 1 mL each). The cells were either treated with 37°C or 45°C pre-equilibrated medium. The samples treated with 37°C medium were placed in a 37°C CO2 incubator and incubations continued for 72 hours. The plates containing the 45°C equilibrated medium were placed at in a 45°C CO2 incubator, and allowed to incubate for an additional 15 minutes. At the end of this time period, plates were transferred to the 37°C CO2 incubator where they remained for 72 hours. Cell viability was evaluated using the cell titer blue kit (Promega, Madison, WI, USA).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1 ZHER2-GS-Cys

The efficacy of targeted nanoparticles depends on the desired ligand-receptor interactions. In the liposome field, immunoliposomes are usually generated by ligating the targeting antibody to the head group region of pegylated phospholipids bearing functional groups [19]. These immunoliposomes have served as suitable nanoparticles for receptor mediated targeting including HER2-specific formulations. The HER2-specific Affibody is an attractive alternate candidate for targeting breast cancer [12,13,20]. Since our previous HER2-specific Affibody-conjugated liposome preparations [10] did not specifically bind HER2+ cells, we designed a new Affibody construct to be more efficiently exposed to cell surface HER2. With this in mind, we introduced a 7 amino acid spacer at the c-terminus of the Affibody before the engineered cysteine. The design is shown in Figure 1A, and the new modified Affibody molecule is designated as ZHER2-GS-Cys. We have successfully cloned and expressed ZHER2-GS-Cys. Figure 1B shows mobility of ZHER2-GS-Cys on 4–12% Bis-Tris gel.

The molecular weight is 9.5 kDa in agreement with the addition of 7 amino acids in comparison to the original Affibody. Next we confirmed the ability of ZHER2-GS-Cys to bind to HER2-expressing cells. Data shown in Figure 1S clearly show that this molecule binds to HER2+ cells (SK-BR-3) and not MDA-MB-468 cells (HER2−).

3.2 HER2+ Affisomes

Our design of thermosensitive Affisomes was essentially as previously reported [10]. Since our objective is to make TTL, DPPC liposomes were used due to their known property of content release at ≈41°C, the result of phase-transition effects [3]. All liposomes used in this study were prepared from DPPC:DSPE-PEG2000-Mal at 96:4 mole ratio. Calcein (λex/em 494 nm/517 nm) was encapsulated in the liposomes (50 mM) and our preparations also included a fluorescent lipid, rhodamine PE (λex/em 557nm/571nm). Conjugation of ZHER2-GS-Cys to preformed liposomes was achieved via malemide-cysteine chemistry (HER2+ Affisomes). Liposomes without ZHER2-GS-Cys conjugation were used as controls. Conjugation of ZHER2-GS-Cys to liposomes was confirmed as described (data not shown)[10]. Our initial experiments included optimization of maximum conjugation efficiency by using various concentrations of ZHER2-GS-Cys with known concentrations of liposomes. We determined that a ratio of 200 µg ZHER2-GS-Cys for 10 mg liposomal phospholipids (containing 1.43 mg DSPE-PEG2000-Mal) resulted in maximum conjugation (data not shown). Therefore these ratios were used for all subsequent preparations. ZHER2-GS-Cys conjugation did not affect the physical properties of liposomes (see Methods section and supplemental content, Figure 2S). Next we examined the HER2+ Affisomes-receptor interactions using cells expressing HER2.

3.3 HER2+ Affisome-Cell Interactions

Successful application of Affisomes will depend on their specific interactions with cellular receptors followed by intracellular accumulation. In vivo applications will also depend on the ability of Affisomes to deliver their contents within defined space and time. Therefore we evaluated the association of Affisomes to SK-BR-3 (HER2+) cells under a variety of experimental conditions using fluorescence microscopy and/or FACS. MDA-MB-468 cells (HER2−) were used to assess any non-specific interactions. In a typical binding experiment, we used a ratio of 100–150 nmol Pi (containing 1–1.5 µg ZHER2-GS-Cys) representing liposomal phospholipids for 105 cells. The results from these experiments are described below.

3.3.1 HER2+ Affisomes bind to SK-BR-3 cells

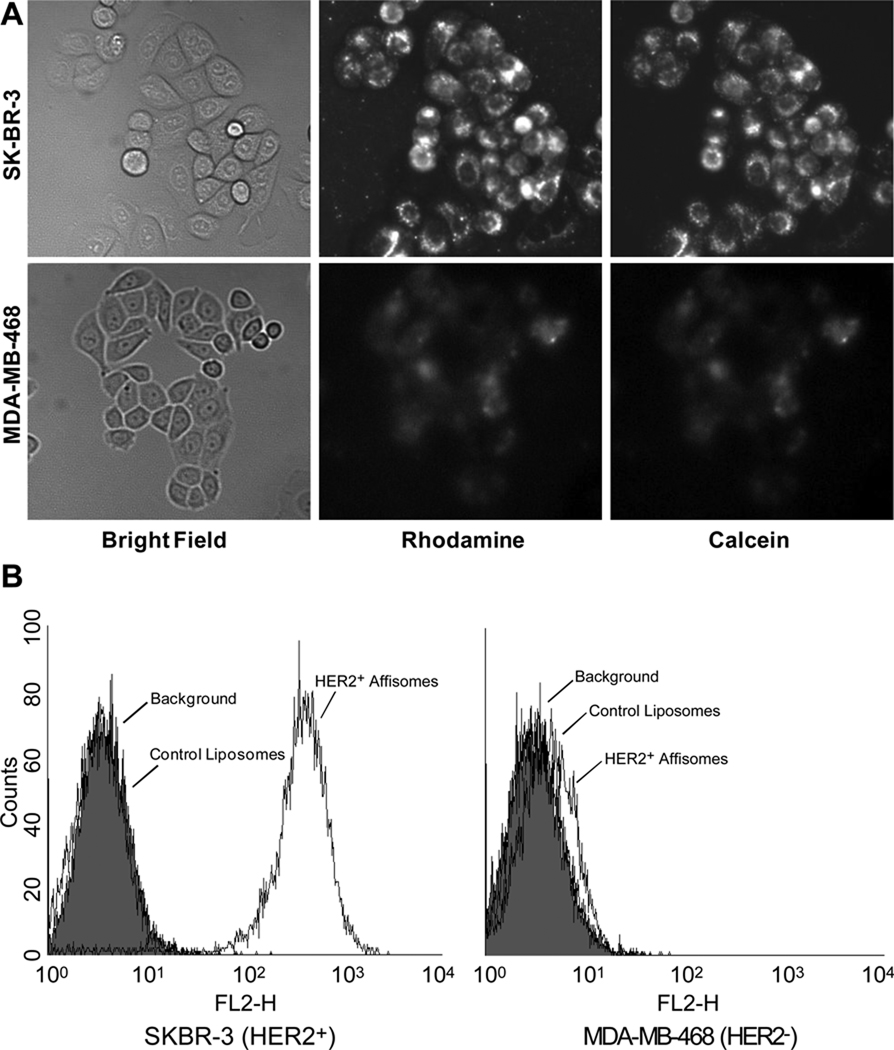

In our first experiments, Affisomes were incubated with cells (plated on cell culture plates) for 1 hour at 37°C and binding/uptake was determined by monitoring fluorescence associated with cells. Figure 2A shows cell associated rhodamine and calcein fluorescence following incubation of Affisomes with cells. It is clear from the data that Affisomes bound with much greater affinity to HER2+ SK-BR-3 cells. Under identical conditions, significantly less Affisome binding was observed when HER2− MDA-MB-468 cells were used. The HER2 specific association of Affisomes was observed for both the lipid probe rhodamine and water soluble dye calcein indicating that Affisomes remained intact during these incubations.

Figure 2. Binding of HER2+ Affisomes to HER2+ Cells.

A) Microscopy: Cells (SK-BR-3 or MDA-MB-468) were plated in 6-well cluster plates (105/well) 48 hours prior to binding experiments. Fluorescently labeled Affisomes were added at a ratio of 10 µg Z-HER2-GS-Cys per well, and incubations were continued at 37°C for two hours. Control liposomes (non-targeted) containing similar lipid content to Affisomes were also incubated with the cells under identical conditions. At the end of incubations, cells were washed with PBS-1%BSA (1 ml ×2), and images were captured for calcein and rhodamine fluorescence using a Nikon TE200 inverted fluorescence microscope, and a 40X (1.30 NA) objective lens.

B) FACS analysis: The cells and Affisomes were incubated as above, lifted with cell dissociation buffer, resuspended in PBS-1%BSA at a concentration of 2×105 cells/ml, and the samples were analyzed for Rhodamine fluorescence. The data is representative of at least 3 independent experiments.

Our results based on FACS analysis are in agreement with the microscopy data (Figure 2B). Cells incubated with Affisomes were harvested using cell dissociation buffer and analyzed by FACS (see Methods/supplemental contents). Figure 2B (left panel) shows results using SK-BR-3 cells. There was a significant increase in rhodamine fluorescence when HER2+ Affisomes were incubated with cells, as compared to control liposomes. In contrast, MDAMB-468 cells did not show any significant binding above background with either Affisomes or control liposomes (Figure 2B, right panel). We also monitored the calcein fluorescence and made similar observations (data not shown). These results further confirm that HER2+ Affisomes bind to cells via HER2.

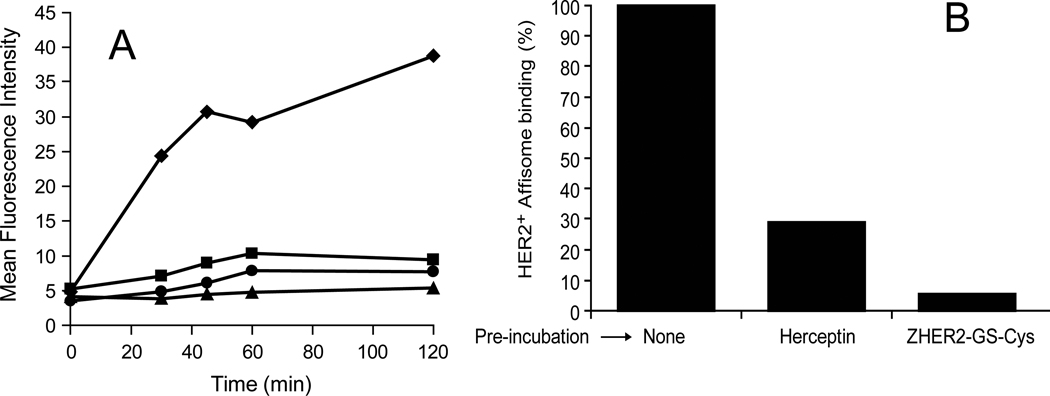

3.3.2 Time dependent association of HER2+ Affisomes to cell

It has been previously demonstrated that the HER2+ Affibody binds to receptor expressing cells with high affinity. Maximum binding is achieved within 2.5 hours of incubation [21]. It can be postulated that the multimeric nature of Affibody present on the surface of liposomes may alter the receptor binding kinetics. Therefore we examined the time dependent binding of Affisomes to SK-BR-3 cells at 37°C. At various time points the samples were analyzed for rhodamine fluorescence by FACS (see Methods section). The values presented in Figure 3 reflect mean fluorescence intensity of rhodamine for samples at a given time point. Maximum binding of HER2+ Affisomes to SK-BR-3 cells occurred within 45 minutes (diamonds, Figure 3A).

Figure 3. HER2-mediated interactions of Affisomes at 37°C.

A) Time dependence of Affisome Binding: Cells (3×105 cells on 6-well cluster plates) were incubated with equivalent amounts of either fluorescently labeled Affisomes or non-targeted, control liposomes (5–10 µg ZHER2-GS-Cys) for 30 minutes to 2 hours. At each time point, cells were lifted with cell dissociation buffer and washed three times with PBS-1%BSA. Samples were then resuspended to 6×105 cells/ml and examined by FACS for rhodamine fluorescence. The data are presented as the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of calcein as a function of time. (Diamonds: HER2+ Affisomes/SK-BR-3; Squares: Control (non-targeted) liposomes/SK-BR-3; Triangles: HER2+ Affisomes/MDA-MB-468; Circles: Control (non-targeted) liposomes/MDA-MB-468).

B) HER2-mediated interactions of HER2+ Affisomes SK-BR-3 cells (105/well) were plated on a 12-well cluster until confluent. Samples were incubated with either excess Herceptin or free ZHER2-GS-Cys (10 µg) at 4°C for 1 hour. Unbound molecules were removed by washing with PBS-1%BSA, and samples were incubated with fluorescently labeled Affisomes (5–10 µg ZHER2-GS-Cys) for 1 hour at 4°C. Cells were resuspended to 2×105 cells/ml for FACS analysis. Data represent percent Affisomes binding in the presence of competing molecules taking untreated cells as 100%. The data presented are based on rhodamine fluorescence.

On the other hand, we did not observe any significant increase in binding over time for control liposomes/SKBR-3 cells (squares). Similarly, MDA-MB-468 cells showed no significant binding with either Affisomes (triangles) or control liposomes (circles). These results are in agreement with those shown in Figure 2. A dose-response curve of average fluorescence following incubation of HER2+ Affisomes to SK-BR-3 cells at 37°C for 1 hr yielded an IC50 of 0.9 µM Affibody conjugated to liposomes (data not shown). Recently Zielinsli et al [22] have reported that the binding affinities of unconjugated (free) HER2+ Affibody and a modified affibody (Affitoxin, affibody conjugated to the toxin) were 2.16×10−5 and 1.1× 10−3 µM, respectively. Presumably Affisomes being larger particles may give rise to steric hindrance, and therefore less accessibility to the receptor resulting in lower affinity than the original molecule. Therefore, even with lower affinities, the cytosolic delivery of entrapped contents may be achieved.

3.3.3 Binding of HER2+ Affisomes to SK-BR-3 cells is inhibited by free ZHER2-GS-Cy

Although the data presented in Figures 2 and 3A suggest that Affisomes interact with cells via specific associations with HER2, we wished to further confirm the specificity of binding in a competition assay using the free ZHER2-GS-Cys. It is known that the HER2-specific monoclonal antibody Herceptin (currently in use for patient treatment) interacts with cellular HER2 via an alternate site than HER2-specific Affibody [20]. Therefore we compared the ability of Herceptin and ZHER2-GS-Cys to block Affisome interactions with SK-BR-3 cells. The data presented in Figure 3B show Affisome binding as percent of samples that were not pre-incubated with Herceptin or ZHER2-GS-Cys. As expected, Affisome binding was completely blocked when cells were pre-incubated with free ZHER2-GS-Cys (Figure 3B). Interestingly, we observed a partial decrease in Affisome binding when cells were pre-incubated with Herceptin. Although Herceptin does not compete with the Affibody binding site on cell surface expressed HER2, it is possible that Herceptin may cause receptor aggregation on the cell surface. Free Affibody, being a small molecule, is not limited by steric constraints when accessing its binding domain on the receptor. On the other hand, steric constraints may contribute to the observed partial inhibition (Herceptin mediated) of Affisome binding. It is also likely that Affisome binding being multimeric in nature may require multiple receptors present in concert on the surface of cells. Further experiments are needed to fully understand the molecular interactions resulting in these observed effects.

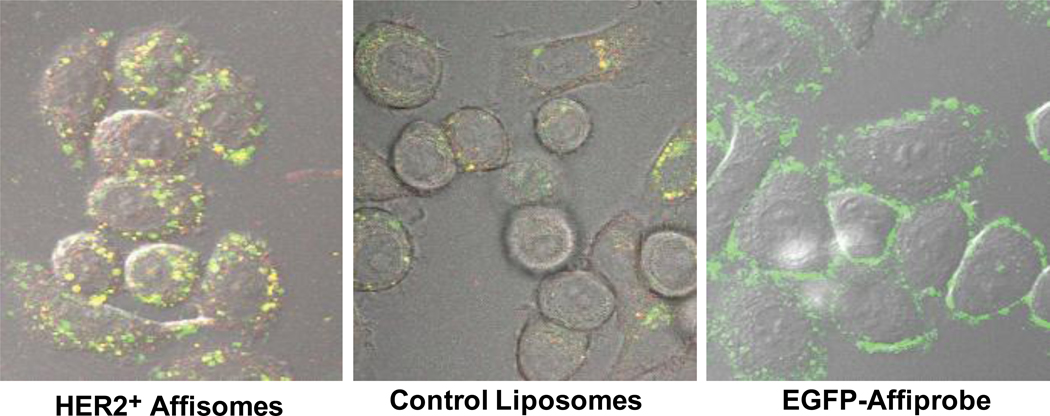

3.4 Intracellular Localization of HER2+ Affisomes

The data presented above (Section 3.3 and Figures 2–3) demonstrate that HER2+ Affisomes interact with cells via HER2. As mentioned before, it is critical that Affisomes are taken up by receptor-mediated endocytosis for drug delivery applications. Although binding of free HER2-specific Affibody to HER2 does not result in receptor internalization [23], multivalent interactions of HER2+ Affisomes with the receptor may facilitate intracellular uptake due to the particulate nature of Affisomes. To answer this question, we incubated SK-BR-3 cells with Affisomes (see Methods) and examined the intracellular uptake of these Affisomes by confocal microscopy. The results presented in Figure 4 clearly demonstrate that HER2+ Affisomes are taken up by the cells and accumulate intracellularly. Control thermosensitive liposomes that were not conjugated with ZHER2-GS-Cys also accumulated in cells (presumably via non-specific endocytic mechanisms). It is evident from the images shown in Figure 4 that the degree of accumulation of HER2+ Affisomes was significantly greater than control liposomes. These results are in agreement with our binding data (Figures 2 and 3). Since HER2-EGFP Affiprobe does not undergo internalization upon binding to cell surface expressed HER2 [18] we used this molecule as control in our experiments. There was no accumulation of Affiprobe in the cells and majority of EGFP fluorescence was confined on the cell surface (Figure 4). This control experiment further substantiates our Affisome internalization results. Based on temperature-dependent intracellular localization of Affisomes (Figure 4), we predict that the affisomes are taken up by receptor-mediated endocytosis. However, further experiments are needed to examine the exact cellular mechanism(s) that result in intracellular accumulation of Affisomes in receptor-bearing cells.Recently Beuttler et al [12] showed that Affibody-conjugated liposomes may serve as suitable drug delivery carriers. In this study the targeting molecule was Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR) and a non-triggerable liposome formulation was used. It may be noted that Herceptin (a monoclonal antibody to HER2) is currently in use for breast cancer treatment. Therefore our focus is to develop nano drug delivery tools to target HER2 and it is conceivable that a formulation bearing on demand drug release properties will have a clear advantage over conventional formulations. Several strategies have been explored for decades to develop tunable liposomes for site-specific drug delivery. The widely examined approaches to release drugs from liposomes include pH, enzymes, light, and heat. Among these, thermosensitive liposomes (non-targeted) are the best studied systems for localized drug release in vivo [1] and are being tested in Phase III clinical trials for breast cancer and hepatocellular carcinoma (www.clinicaltrials.gov, identifier #NCT00346229 and #NCT00441376). Based on this knowledge, we are developing HER2-specific Affibody-conjugated thermosensitive liposomes as the HER2-specific TTLs for improved delivery of therapeutics for breast cancer therapy. Here we have demonstrated that our HER2+ Affisomes are selectively localized in the interior of SK-BR-3 cells and efficiently release their contents upon treatment with mild hyperthermia. The results are presented in the next section.

Figure 4. Cellular uptake of HER2+ Affisomes at 37°C.

Cells (105) were plated on 35 mm glass bottom, poly-d-lysine coated dishes (MatTek Corporation), incubated for 1 hour with either HER2+ Affisomes (5–10 µg ZHER2-GS-Cys) or control, non-targeted liposomes (equivalent to phospholipid content of Affisomes), and washed twice with PBS and internalization was determined by confocal microscopy. We used EGFP-Affiprobe (10–20 µg per sample) as a control. The data presented here show a representative stack from various samples. Images shown are composites of fluorescence and DIC. Left panel: HER2+ Affisomes, center panel: Control Liposomes, Right panel: EGFP-Affiprobe. The images are representative of at least 3 independent experiments.

3.5 Hyperthermia-induced intracellular release of contents from HER2+ Affisomes

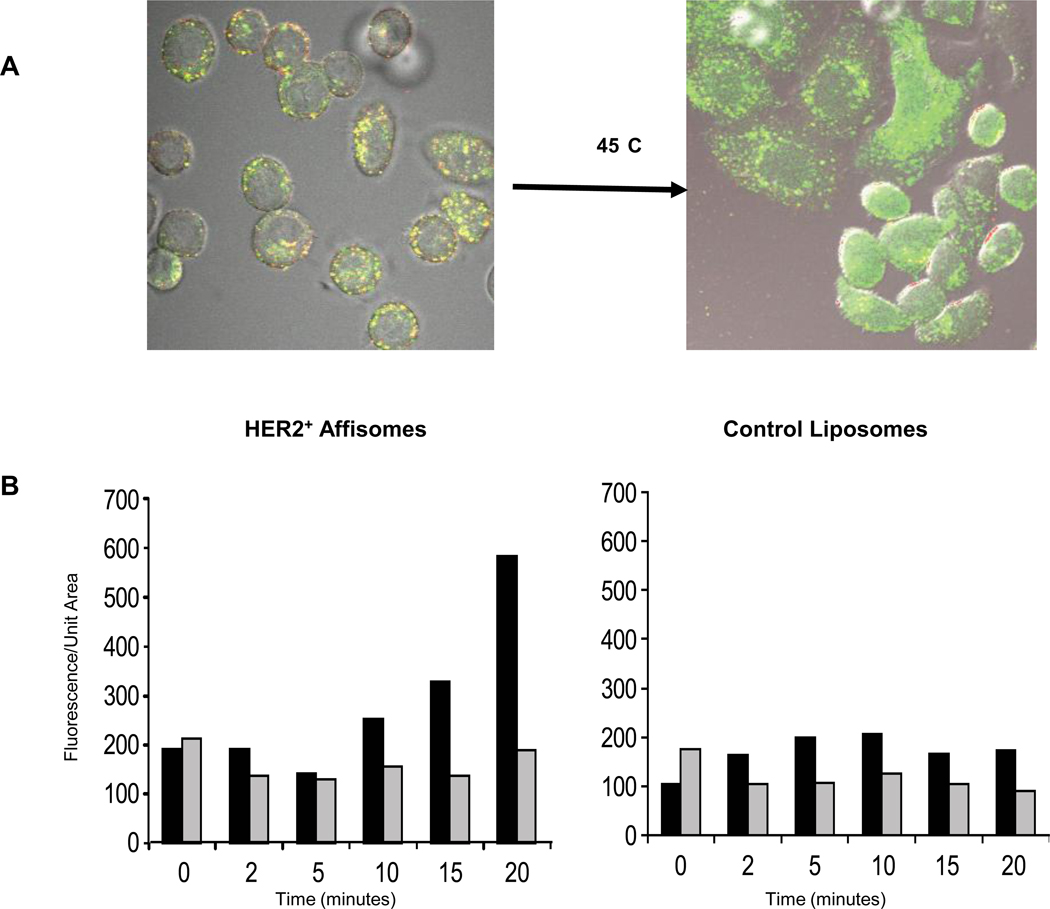

The experimental set up for hyperthermia-induced release of Affisome contents is depicted in supplemental contents (Figure 3S). Since calcein was entrapped at its quenched concentration, its release from Affisomes was monitored by an increase in fluorescence intensity due to relief of self-quenching. As our Affisomes are also labeled with the lipid probe Rhodamine-PE (that is not quenched) we also monitored rhodamine fluorescence to validate the release of calcein. SK-BR-3 cells were incubated with Affisomes for 1 hour at 37°C and unbound Affisomes were removed. Images were acquired before the onset of hyperthermia treatment. For our proof-of-principle experiments, we performed experiments at 45°C, slightly higher than the phase-transition release temperature of DPPC liposomes (41°C). The elevated temperatures used for these experiments were not detrimental to the cells based on a cell viability assay (data not shown). The detailed setup of the experiment, image analysis, and quantitation is given in the Methods and supplemental content sections.

Figure 5A shows a snapshot of cells following treatment at 45°C for 20 minutes. As can be seen in the images, there was a dramatic increase in calcein fluorescence upon exposure of the samples to 45°C. We attribute this increase in fluorescence to the leakage of calcein from the liposomes and its dilution in the cell interior. It is also interesting to note that majority of calcein remained associated with the cells, confirming that the hyperthermia treatment conditions used here did not compromise cell viability.

Figure 5. Hyperthermia-induced intracellular release of calcein from HER2+ Affisomes.

A) HER2+ cells were incubated with Affisomes for one hour at 37°C under microscope stage. The microscope stage and sample were heated to 45°C for up to 20 minutes and exposed fluorescence was imaged. The images are representative of at least 3 independent experiments.

B) Cell fluorescence as a function of time at 45°C for both HER2+ Affisomes (left panel) and control, non-targeted liposomes (right panel) was quantitated using the Metamorph software. The fluorescence of calcein (black bars) and rhodamine (gray bars) was determined by generating regions of interests around cells, measuring their average fluorescence intensity/unit area, and taking the average of these values over the course of 3 independent experiments.

Next we determined the effect of active targeting on the temperature-induced intracellular delivery of calcein from Affisomes. In our previous study we have demonstrated that non-thermosensitive liposomes do not release calcein at temperatures above 42°C [10], therefore we used non-targeted thermosensitive liposomes as controls in our experiments. A series of images were captured either at 37°C or 45°C as described above and data analysis was performed based on quantitation of calcein and rhodamine fluorescence. Figure 5B shows results from these analyses and the values are expressed as calcein or rhodamine fluorescence per unit area for given time point. The zero time point represents samples incubated at 37°C prior to heating at 45°C. There was an increase in calcein fluorescence with time for Affisomes samples following incubation at 45°C (Figure 4B left panel, black bars). As mentioned before, the increase in fluorescence of calcein reflects the release from liposomes in the cells. The onset of calcein release was observed only after 10 minutes of incubation. As rhodamine-PE is used at its non-quenched concentrations (0.1 mol % of total liposomal lipids), we did not observe any change in levels of rhodamine fluorescence over time (Figure 5B, left panel, grey bars). Since there was no change in rhodamine fluorescence with time at 45°C within our experimental setup, we conclude that the observed increase in calcein fluorescence was specific to the hyperthermia-induced effect. Figure 5B (right panel) shows results when non-targeted thermosensitive liposomes were used under identical conditions.

Although it is expected that the control liposomes that are internalized by cells should release calcein upon 45°C treatment, we were not able to see a noticeable increase in calcein fluorescence (Figure 5B right panel, black bars). We surmise that the total uptake of control liposomes is significantly less as compared to that of Affisomes (see Figures 2 and 3) and hence the small amount of calcein released was close to the background fluorescence levels. Following the hyperthermia-induced calcein release experiments, our next experiments were designed to demonstrate the potential of HER2+ Affisomes for targeted and triggered delivery of cancer therapeutics. Results obtained from these studies are presented below.

3.6: Accumulation and Cytotoxicity of DOX-loaded HER2+ Affisomes

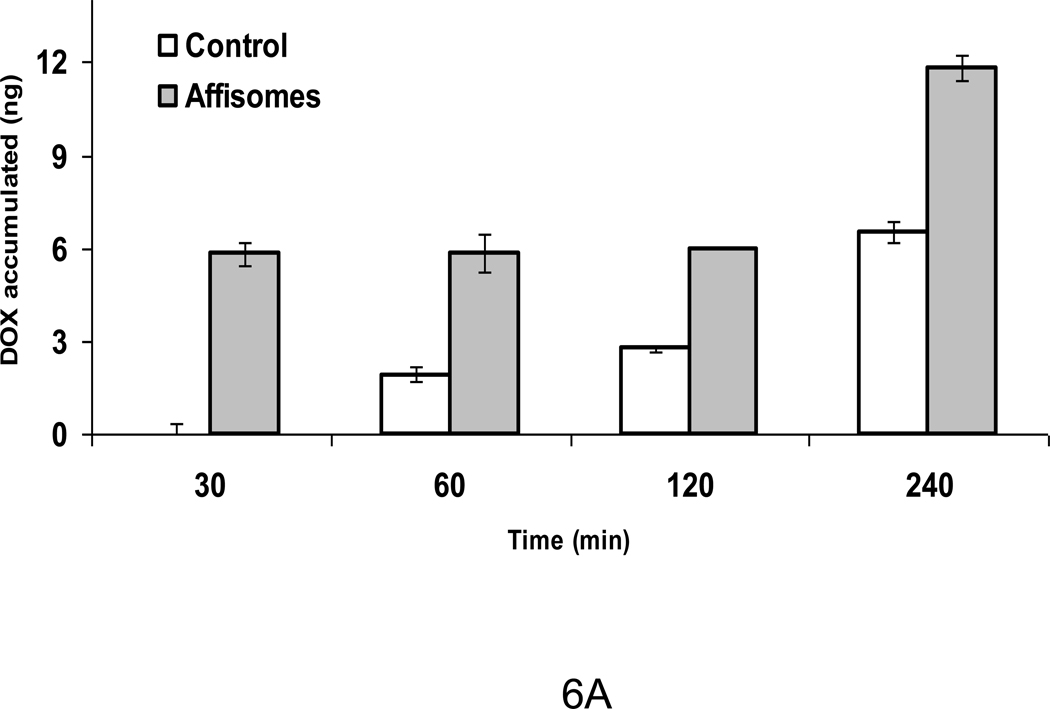

Immunoliposomes have long been studied as vehicles for site-specific delivery of drugs and pharmaceutics[8]. In the area of HER2 targeting, anti-HER2 scFv-DOXIL has been shown to improve DOX-mediated cell killing in vitro as well as in animal studies[24]. It can be predicted that the localized delivery of DOX from targeted liposomes may further improve the drug’s efficacy by decreasing its diffusion distance and thereby increasing its local concentration at target sites. Our data presented above show that HER2+ Affisomes deliver their contents (calcein) upon mild hyperthermia treatment (Figure 5A). To further confirm the potential of these formulations, we encapsulated DOX using the well-established ammonium sulfate remote loading protocol [25], followed by the conjugation of ZHER2-GS-Cys to the surface of DOX-loaded liposomes (DOX-loaded HER2+ Affisomes). Liposomal DOX loading and efficiency of affibody was determined (Figure 4S). Results on cellular interactions of DOX-loaded HER2+ Affisomes using SK-BR-3 cells are shown in Figure 6A. First we determined the accumulation of DOX-loaded HER2+ Affisomes at 37°C (see Methods).

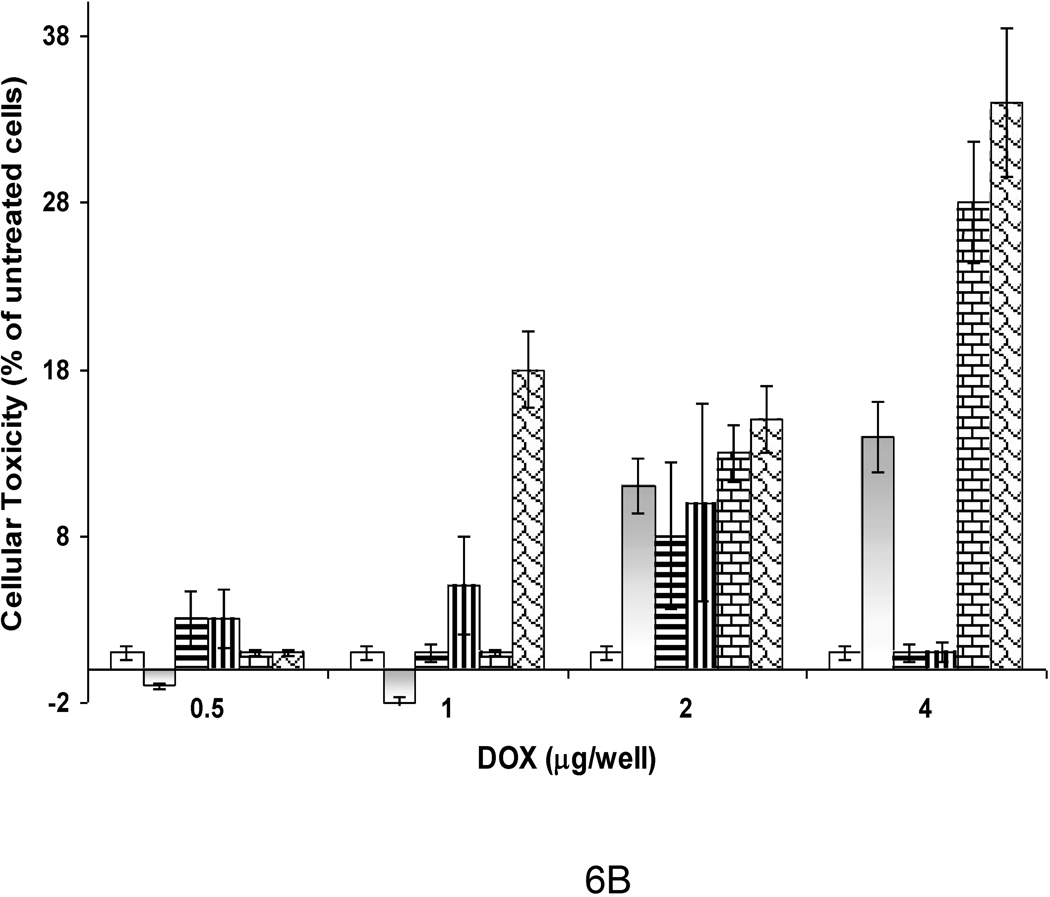

Figure 6. Interaction of Doxorubicin-loaded HER2+ Affisomes with SK-BR-3 cells.

A) Cellular Accumulation of DOX-loaded affisomes. DOX-loaded HER2+ Affisomes or control liposomes (containing equivalent of 15 µg DOX per well) were incubated with SK-BR-3 cells (plated on six-well clusters) at 37°C for 30–240 minutes at 37°C. At the end of incubations, cells were washed with PBS-BSA, and suspended using the cell-dissociation buffer. Cell-associated DOX was measured following lysis with TX100 (Methods section). Control (non-targeted) liposomes, open bars. HER2+ Affisomes, grey bars. The error bars (S.D.) represent values from three samples within a single experiment. The results were reproducible from at least two independent experiments.

B) Cellular Toxicity of DOX-loaded HER2+ Affisomes. Control (non-targeted) liposomes, HER2+ Affisomes or Doxil were diluted in culture medium to desired concentrations and were added to SK-BR-3 cells (plated on 48-well clusters) in duplicates. The samples were incubated for 1 hour at 37°C, and were washed to remove unbound particles. The plates were either maintained at 37°C for 72 hours or treated with 45°C buffer for 15 minutes followed by incubations at 37°C for 72 hours. Cell viability was determined (Methods section). The data represent percent of cellular toxicity, taking viability of untreated cells as 100%. Error bars (S.D.) represent values from three samples within a single experiment. Open bars, control liposomes (37°C). Grey bars, control liposomes (45°C). Horizontal bars, Doxil (37°C). Vertical bars, Doxil (45°C). Brick bars, HER2+ Affisomes (37°C). Shingle bars, HER2+ Affisomes (45°C).

We observed a significant increase in the association of DOX-loaded HER2+ Affisomes when compared with non-targeted control liposomes. During the initial 30 minutes of incubations, we observed only accumulation of DOX-loaded HER2+ Affisomes. However at prolonged incubations, control liposomes also demonstrated binding to cells albeit at a lower efficiency compared to HER2+ Affisomes (as expected). These results are consistent with our data presented on the interactions of SK-BR-3 cells with fluorescent HER2+ Affisomes.

Next, we examined the effect of liposomal DOX on cellular viability (Figure 6B) before and after exposure to mild hyperthermia. SK-BR-3 cells (HER2+) were incubated with increasing concentrations of Affisomes for 72 hours at 37°C and cell viability was determined. The effect of hyperthermic treatment at 45°C was also evaluated in these experiments as described (Methods section). It is evident from the data that HER2+ Affisomes were able to mediate improved cytotoxicity at increasing concentrations of liposomes tested, and the effects were more pronounced when samples were pre-exposed to 45°C. For instance, at 1 µg liposomal DOX (104 cells), a 2–3 fold increase in cellular toxicity was observed when HER2+ Affisomes (bricks, 37°C., shingles, 45°C, Fig. 8) were used, in comparison to non-targeted control liposomes (open bars, 37°C., greybars, 45°C, Fig. 6B). Similarly, we did not observe a significant effect on viability of cells incubated with Doxil (horizontal bars, 37C., vertical bars, 45C, Fig. 6B). The exposure of the Affisome-cell complexes to mild hyperthermia at 4 µg dose resulted in higher cytotoxicity (shingles, Fig. 6B). Hyperthermia treatment also had an effect on control liposomes (the non-targeted thermosensitive formulation) as expected (grey bars, Figure 6B).

Interestingly, we did not observe any effect of heat treatment on the viability of cells incubated with Doxil[26,27] (vertical bars, 37°C, horizontal bars, 45°C, Fig. 6B). This is expected as the Doxil formulation primarily contains hydrogenated soy PC (C18 PC, Tm 55°C) and cholesterol, which is known to obliterate the phase transition of gel-phase phospholipids. Additional controls in our cell viability experiments included empty liposomes (not loaded with DOX) to examine non-specific effects mediated by liposomal lipids. We did not observe any cell killing at concentrations equivalent to the amounts of liposomes up to 4 µg liposomal DOX used in our cytotoxicity experiments (not shown). The extent of improved cytotoxicity in vitro observed using the triggered release of therapeutics from targeted lipid-based nanoparticles is in agreement with published literature [7,15,28], and is likely to bear significant effects in future animal studies.

Taken together, data presented in Figure 6 suggest that our HER2+ Affisomes may serve as possible candidates for targeted-triggered delivery of anticancer agents to combat HER2+ breast cancer.

4. Conclusions

Currently available cancer chemotherapies can be significantly improved by nanoparticle mediated drug delivery systems. Among various nanoparticle systems currently in development, liposomes are the most studied and Doxil (Liposomal Doxorubicin) is one of the first nanoparticles to be approved by FDA for patient care. It can be imagined that liposomes bearing targeting molecules and possessing triggering properties will be ideal choices for future therapies. Several targeted liposomes (primarily immunoliposomes) have shown to be promising candidates for enhanced cellular uptake, however none of these liposomes have yet to reach the clinic. In an effort to develop the next generation of liposomes for localized drug delivery, our objective was to combine the targeting properties of HER2-specific Affibody molecules with the thermosensitive properties of liposomes (HER2+ Affisomes). In this report, we have successfully demonstrated that the HER2+ Affisomes are suitable vehicles for intracellular delivery of liposome-entrapped therapeutics. To our knowledge this is the first example demonstrating the application of liposomes coupled with both targeting potential as well as on demand drug release properties. We propose that further investigation of these nanoparticles for the in-vivo delivery of anti-cancer agents will prove to be beneficial for future breast cancer treatment.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported [in part] by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research. This project has been funded in whole or in part with federal funds from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, under contract HHSN261 200 800 001E. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. government.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference List

- 1.Needham D, Dewhirst MW. The development and testing of a new temperature-sensitive drug delivery system for the treatment of solid tumors. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2001;53:285–305. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(01)00233-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shum P, Kim JM, Thompson DH. Phototriggering of liposomal drug delivery systems. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2001;53:273–284. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(01)00232-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yatvin MB, Weinstein JN, Dennis WH, Blumenthal R. Design of liposomes for enhanced local release of drugs by hyperthermia. Science. 1978;202:1290–1293. doi: 10.1126/science.364652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Needham D, Anyarambhatla G, Kong G, Dewhirst MW. A new temperature-sensitive liposome for use with mild hyperthermia: characterization and testing in a human tumor xenograft model. Cancer Res. 2000;60:1197–1201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weinstein JN, Magin RL, Zaharko DS, Yatvin MB, Blumenthal R. Use of Hyperthermia for Selective Localization of Liposomal Methotrexate in Tumors. Biophysical Journal. 1979;25:A291. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Negussie AH, Miller JL, Reddy G, Drake SK, Wood BJ, Dreher MR. Synthesis and in vitro evaluation of cyclic NGR peptide targeted thermally sensitive liposome. J. Control Release. 2010;143:265–273. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2009.12.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Puri A, Loomis K, Smith B, Lee JH, Yavlovich A, Heldman E, Blumenthal R. Lipid-based nanoparticles as pharmaceutical drug carriers: from concepts to clinic. Crit. Rev. Ther. Drug Carrier Syst. 2009;26:523–580. doi: 10.1615/critrevtherdrugcarriersyst.v26.i6.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Allen TM. Liposomes. Opportunities in drug delivery. Drugs. 1997;54 Suppl. 4:8–14. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199700544-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Torchilin VP. Liposomes as targetable drug carriers. Crit Rev Ther Drug Carrier Syst. 1985;2:65–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Puri A, Kramer-Marek G, Campbell-Massa R, Yavlovich A, Tele SC, Lee SB, Clogston JD, Patri AK, Blumenthal R, Capala J. HER2-Specific Affibody-Conjugated Thermosensitive Liposomes (Affisomes) for Improved Delivery of Anticancer Agents. Journal of Liposome Research. 2008;18:293–307. doi: 10.1080/08982100802457377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alexis F, Basto P, Levy-Nissenbaum E, Radovic-Moreno AF, Zhang L, Pridgen E, Wang AZ, Marein SL, Westerhof K, Molnar LK, Farokhzad OC. HER-2-targeted nanoparticle-affibody bioconjugates for cancer therapy. ChemMedChem. 2008;3:1839–1843. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.200800122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beuttler J, Rothdiener M, Muller D, Frejd FY, Kontermann RE. Targeting of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)-expressing tumor cells with sterically stabilized affibody liposomes (SAL) Bioconjug. Chem. 2009;20:1201–1208. doi: 10.1021/bc900061v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lofblom J, Feldwisch J, Tolmachev V, Carlsson J, Stahl S, Frejd FY. Affibody molecules: engineered proteins for therapeutic, diagnostic and biotechnological applications. FEBS Lett. 2010;584:2670–2680. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Orlova A, Tolmachev V, Pehrson R, Lindborg M, Tran T, Sandstrom M, Nilsson FY, Wennborg A, Abrahmsen L, Feldwisch J. Synthetic affibody molecules: a novel class of affinity ligands for molecular imaging of HER2-expressing malignant tumors. Cancer Res. 2007;67:2178–2186. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Loomis K, Smith B, Feng Y, Garg H, Yavlovich A, Campbell-Massa R, Dimitrov DS, Blumenthal R, Xiao XD, Puri A. Specific targeting to B cells by lipid-based nanoparticles conjugated with a novel CD22-ScFv. Experimental and Molecular Pathology. 2010;88:238–249. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2010.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.AMES BN, DUBIN DT. The role of polyamines in the neutralization of bacteriophage deoxyribonucleic acid. J Biol Chem. 1960;235:769–775. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rawat SS, Eaton J, Gallo SA, Martin TD, Ablan S, Ratnayake S, Viard M, KewalRamani VN, Wang JM, Blumenthal R, Puri A. Functional expression of CD4, CXCR4, and CCR5 in glycosphingolipid-deficient mouse melanoma GM95 cells and susceptibility to HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein-triggered membrane fusion. Virology. 2004;318:55–65. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2003.08.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lyakhov I, Zielinski R, Kuban M, Kramer-Marek G, Fisher R, Chertov O, Bindu L, Capala J. Chembiochem. 2010;11:345–350. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200900532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nellis DF, Giardina SL, Janini GM, Shenoy SR, Marks JD, Tsai R, Drummond DC, Hong K, Park JW, Ouellette TF, Perkins SC, Kirpotin DB. Preclinical manufacture of anti-HER2 liposome-inserting, scFv-PEG-lipid conjugate. 2. Conjugate micelle identity, purity, stability, and potency analysis. Biotechnol Prog. 2005;21:221–232. doi: 10.1021/bp049839z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee SB, Hassan M, Fisher R, Chertov O, Chernomordik V, Kramer-Marek G, Gandjbakhche A, Capala J. Affibody molecules for in vivo characterization of HER2-positive tumors by near-infrared imaging. Clin. Cancer Res. 2008;14:3840–3849. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Steffen AC, Wikman M, Tolmachev V, Adams GP, Nilsson FY, Stahl S, Carlsson J. In vitro characterization of a bivalent anti-HER-2 affibody with potential for radionuclide-based diagnostics. Cancer Biother. Radiopharm. 2005;20:239–248. doi: 10.1089/cbr.2005.20.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zielinski R, Lyakhov I, Jacobs A, Chertov O, Kramer-Marek G, Francella N, Stephen A, Fisher R, Blumenthal R, Capala J. Affitoxin-A Novel Recombinant, HER2-specific, Anticancer Agent for Targeted Therapy of HER2-positive Tumors. Journal of Immunotherapy. 2009;32:817–825. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e3181ad4d5d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wallberg H, Orlova A. Slow internalization of anti-HER2 synthetic affibody monomer 111In-DOTA-ZHER2:342-pep2: implications for development of labeled tracers. Cancer Biother. Radiopharm. 2008;23:435–442. doi: 10.1089/cbr.2008.0464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Laginha KM, Moase EH, Yu N, Huang A, Allen TM. Bioavailability and therapeutic efficacy of HER2 scFv-targeted liposomal doxorubicin in a murine model of HER2-overexpressing breast cancer. Journal of Drug Targeting. 2008;16:605–610. doi: 10.1080/10611860802229978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haran G, Cohen R, Bar LK, Barenholz Y. Transmembrane Ammonium-Sulfate Gradients in Liposomes Produce Efficient and Stable Entrapment of Amphipathic Weak Bases. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1993;1151:201–215. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(93)90105-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gabizon A, Catane R, Uziely B, Kaufman B, Safra T, Cohen R, Martin F, Huang A, Barenholz Y. Prolonged circulation time and enhanced accumulation in malignant exudates of doxorubicin encapsulated in polyethylene-glycol coated liposomes. Cancer Res. 1994;54:987–992. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gabizon A, Shmeeda H, Barenholz Y. Pharmacokinetics of pegylated liposomal Doxorubicin: review of animal and human studies. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2003;42:419–436. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200342050-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.O'Donnell RT, Martin SM, Ma Y, Zamboni WC, Tuscano JM. Development and characterization of CD22-targeted pegylated-liposomal doxorubicin (IL-PLD) Invest New Drugs. 2010;28:260–267. doi: 10.1007/s10637-009-9243-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.