Abstract

There are substantial disparities in dispensing patterns of long-term control medications for asthma among children in Puerto Rico with public insurance compared to those with private insurance. Public health insurance policy in Puerto Rico includes the cost of medications in the capitation paid to the primary care physicians and clinics. Survey questionnaires were mailed to all pediatricians enrolled in the Puerto Rico College of Physicians (N = 798) in addition to some pediatricians not enrolled in the College (N = 25) for a total of 823 pediatricians. Of these, 722 were eligible pediatricians with 458 responding to the survey for a response rate of 63.4%. Most of the respondents expressed being moderately to very familiar with the National Asthma Education and Prevention Program guidelines (71.7%) and with the National Asthma Education and Prevention Program recommendations for controller asthma medication use (73.5%). Inadequate capitation to cover asthma medication (86.2%) and lack of adequate health insurance coverage of the patient (83.2%), however, were the most frequent barriers reported by pediatricians for prescribing controller asthma medication to children with public health insurance. The most frequent strategies used to provide controller asthma medication to these children were prescription of oral medications (59.5%) and giving away samples (44.7%). Current public health insurance policy in Puerto Rico creates a disincentive to the appropriate prescription of long-term control medication for children with asthma. To improve the quality of asthma care of children in Puerto Rico, revision of this public health insurance policy is necessary.

Introduction

Long-term control medication such as inhaled corticosteroids, and leukotriene modifiers are recommended for management of persistent asthma by both national and international guidelines.1,2 Regular use of these medications improves asthma control and reduces risk of exacerbations among children with persistent asthma symptoms.3,4 Yet, studies that analyze medical records have demonstrated that children from low-income African American and Latino families are less likely to be prescribed controller medications regardless of insurance coverage, severity of asthma, and sociodemographic characteristics.5,6

Although under-utilization of controller medication use among these children has been widely documented,7–9 there has been little research on adverse incentives of health policies in exacerbating this under-treatment. There is evidence that some policies implemented by public health plans to control health costs may provide adverse incentives and thereby exacerbate disparities in the populations they serve.10 In Puerto Rico, 48.0% of the population is below the federal poverty level and, currently, the government is responsible for financing the health-care costs of 37.5% of the population or 1,476,586 out of a population of 3,942,375 inhabitants on the island.12 Public health services in Puerto Rico are offered by the government to the medically indigent by a capitated payment system through subcontracts with managed care organizations, which in turn subcontract with networks of health providers or independent provider associations. A very low per member per month (PMPM) premium is negotiated with independent provider associations establishing a fixed rate to cover preventive, medical, and diagnostic tests; clinical laboratory tests; X-rays; and emergency and prescription drug services. Therefore, the financial burden of expensive asthma treatments and prescriptions becomes the responsibility of the contracted provider. Research on provider response to drug payment policy suggests that providers are less likely to prescribe medications when they bear the financial risk.12

A recent study by our group documents substantial under-treatment of asthmatic children in the public health sector compared with the private sector in Puerto Rico. This study analyzed claims data from Puerto Rico comparing asthma prescription filling patterns by asthmatic children with uncontrolled asthma, defined by having 2 or more emergency room visits in a year, and found that families with private insurance were dispensed significantly more controller medications than families with public health insurance (48.3% versus 12.0%).13 Although, there are multiple factors that can contribute to these findings, an important factor could be the health policy in Puerto Rico, in which providers bear all the financial risk of medication costs when treating asthmatic children from low-income group with public health insurance, but are not at risk for medication costs when treating children with private insurance.

In this study we examined whether the financial responsibility for asthma medication imposed to pediatricians by the current Puerto Rico health policy is perceived as an adverse incentive to prescribe controller anti-inflammatory medication to asthmatic children with public health insurance. We also assess the strategies pediatricians use to overcome this barrier, their familiarity with and access to asthma medication guidelines, and their beliefs related to prescribing these medications.

Methods

Sample and procedures

Survey questionnaires were mailed to all pediatricians enrolled in the Puerto Rico College of Physicians (N = 798) in addition to 25 pediatricians not enrolled in the College of Physicians, for a total of 823 pediatricians. Of the 823 pediatricians, 103 were not eligible because they were retired, did not live in Puerto Rico, or did not treat children at the time of the survey. Of the 722 eligible pediatricians, 458 responded to the survey for a response rate of 63.4%.

Surveys were mailed to eligible pediatricians between March 26, 2008, and October 1, 2008, with a letter explaining the purpose of the survey and with a stamped return envelope. Mailed follow-up was conducted with a maximum of 3 contacts made for each nonresponding pediatrician. A remuneration of $10.00 was sent to all pediatricians who responded to the survey.

Questionnaire

The measures used for this study are included in the Appendix and consisted of 11 questions that focused on the following domains: (1) demographic information, including sex, years of experience, and percent of children with asthma in the provider's practice; (2) barriers to prescribing controller anti-inflammatory medications; (3) strategies used by pediatricians to provide controller anti-inflammatory medications to children with public insurance, such as providing samples and prescribing generic medications; (4) beliefs about inhaled corticosteroids; and (5) familiarity with and access to general practice guidelines and guidelines specific to controller anti-inflammatory medications use. These measures were obtained from the different validated questionnaires such as the Physician Baseline Asthma Survey, the Physician Asthma Care Education Instrument, the Johns Hopkins Pediatric Asthma Management Study, and the National Asthma Practice Survey.10,14,15 The scale related to medication barriers was modified by the investigators of the study after meeting with several providers in focus groups and in-depth interviews in which this topic was discussed.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to present the characteristics of pediatricians and the barriers and strategies to prescribing controller anti-inflammatory medications.

Results

Characteristics of pediatricians who responded to the survey are shown in Table 1. As demonstrated, the sample was evenly distributed by sex, and a significant majority (70.2%) had >20 years in practice. The majority of pediatricians (78.8%) had a practice composed of children with public and private insurance, whereas a few had a practice solely of children with public practice (3.5%) or solely of private insurance patients (17.0%).

Table 1.

Pediatrician's Characteristics (N = 458)a

| Variables | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 220 | 48.0 |

| Female | 238 | 52.0 |

| Years of experience (year) | ||

| ≤10 | 29 | 6.9 |

| 11–20 | 96 | 22.9 |

| >20 | 295 | 70.2 |

| Pediatric asthma patients per week (%) | ||

| ≤10 | 138 | 32.0 |

| 11 to 20 | 91 | 21.1 |

| 21 to 30 | 88 | 20.4 |

| 31 to 40 | 50 | 11.6 |

| 41 to 50 | 24 | 5.6 |

| >50 | 40 | 9.3 |

| Practice composition | ||

| Both public and private insurance patients | 357 | 78.8 |

| Public insurance only | 16 | 3.5 |

| Private insurance only | 77 | 17.0 |

Entries in table are based on cases with complete data only; therefore, the sample size for each constraint varies slightly because of missing data.

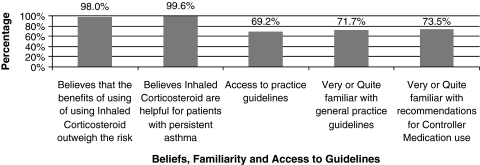

Most respondents expressed that they were moderately or very familiar with the general National Asthma Education and Prevention Program (NAEPP) guidelines from the National Heart and Lung and Blood Institute2 (71.7%) and the recommendations for controller anti-inflammatory medication use (73.5%; Fig. 1). Most pediatricians believed that the benefits of using inhaled corticosteroids outweigh the risks (98.0%) and that inhaled corticosteroids for children with persistent asthma are beneficial (99.6%) (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Provider belief about inhaled cortisosteroid and familiarity and access to guidelines.

The most frequently reported barrier to prescribing controller anti-inflammatory medications to children with asthma covered by public insurance was financial limitations. Limited capitation to cover asthma medication (86.2%) and lack of adequate health insurance coverage of the patient (83.0%) were the most frequent barriers reported (Table 2). Other barriers reported were related to the patient's illness management, such as poor compliance of patient with medical advice (80.0%), poor asthma knowledge (78.4%), as well as poor attendance to follow-up visits (75.4%). Close to half of responding pediatricians (45.6%) reported that fear of side effects was also an important barrier.

Table 2.

Barriers to Appropriate Pharmacologic Treatment for Medicaid Asthmatic Childrena

| |

Strongly agree/agree |

Neutral |

Disagree/strongly disagree |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barriers | N | % | N | % | N | % |

| Limited capitation to cover asthma medications | 350 | 86.2 | 23 | 5.7 | 33 | 8.1 |

| Inadequate health insurance coverage | 342 | 83.0 | 34 | 8.3 | 36 | 8.7 |

| Lack of financial incentives | 245 | 61.1 | 92 | 22.9 | 64 | 16.0 |

| Lack of educational materials or resources | 283 | 69.5 | 74 | 18.2 | 50 | 12.3 |

| Lack of extra personnel to assist in asthma education | 320 | 77.7 | 59 | 14.3 | 33 | 8.0 |

| Poor compliance with medical advice | 332 | 80.0 | 56 | 13.5 | 27 | 6.5 |

| Poor asthma management knowledge of the patient | 324 | 78.4 | 49 | 11.9 | 40 | 9.7 |

| Poor attendance to follow-up visits | 307 | 75.4 | 52 | 12.8 | 48 | 11.8 |

| Fear of side effects of asthma medicines | 186 | 45.6 | 107 | 26.2 | 115 | 28.2 |

Entries in table are based on cases with complete data only; therefore, the sample size for each constraint varies slightly because of missing data.

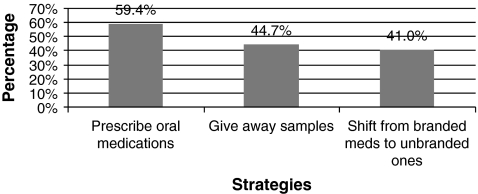

When asked about the strategies they used to provide controller anti-inflammatory medications to children with public insurance and asthma, the majority of respondents said that they prescribed oral medications (59.4%), gave away samples (44.7%), or shifted from branded to generic medications (41.0%; Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Strategies used by pediatricians to provide controller anti-inflammatory medication.

Discussion

Under the present managed care public health insurance policy in Puerto Rico, the financial burden of asthma treatments and prescriptions becomes the responsibility of the contracted provider. This survey documented that physicians perceive this policy as a barrier to the prescription of long-term control medication for children with asthma and public health insurance on the island. Our group has demonstrated substantial under-treatment of children with public insurance compared to those with private insurance.13 Other U.S. surveys found that family financial status was an important barrier for controller anti-inflammatory medication use10,16 Our study documents another financial barrier to appropriate long-term control medication use for children with persistent asthma—Medicaid managed care policies that place the individual physician at financial risk for the cost of these medications.

Pediatricians in our survey reported a number of strategies for providing long-term control medication to children with public health insurance. These strategies include giving away samples, shifting from brand medications to generic, and prescribing oral medications. The survey did not ask pediatricians what generic, oral, or sampled medications they prescribed. At the time of the survey there was no asthma controller medication available that was generic. We suspect that leukotriene modifiers represent only a small number of the oral medications prescribed. Previous research from our group presented elsewhere shows that few children with public insurance in Puerto Rico (5.7% of children with at least one asthma claim) were dispensed leukotrienes in 2005–2006.13

Similar to other Medicaid systems, the Puerto Rico Health Reform has an approved medication formulary based on the NAEPP treatment guidelines.2 The average cost to the physician of the least expensive inhaled corticosteroid medication in the formulary is $84.00 for a 30-day supply, which represents 2 to 3 times their current PMPM capitation. The cost of long-term control medications for asthma that exceeds the PMPM capitation is likely to contribute to the low prescription rates of long-term control medication previously documented.13

Other common barriers to providing asthma care to children from low-income groups reported by pediatricians in this study were lack of personnel to assist in asthma education (78%) and lack of educational resources (70%). This is consistent with surveys of pediatricians elsewhere in the United States.10 Further research is needed to examine the extent to which the low rates of controller medication filling in the island (reported previously)13 are a result of primary nonadherence by the population with publicly financed health insurance and the extent to which it is related to under-prescription by providers.

A majority of pediatricians had access to the guidelines, and close to three-fourths reported familiarity with both the general NAEPP guidelines2 and the recommendations for prescribing controller anti-inflammatory medications. These rates are similar to previous self-reported surveys in the United States that indicate 70%–90% of physicians being aware, having access to a copy, and having read the practice guidelines.16–18 Just under one-third of pediatricians, nevertheless, reported not having a copy, and just over one-quarter of respondent pediatricians reported slight or no familiarity with asthma treatment guidelines. This is troubling, as familiarity with guidelines is an important predictor of guidance adherence.10,16 Our results suggest that access to guidelines and education of physicians on asthma guidelines are needed to improve the care of asthmatic children in Puerto Rico.

The vast majority of pediatricians (99.6%) reported positive beliefs and attitudes toward prescribing controller anti-inflammatory medications. Nonadherence to practice guidelines in spite of familiarity with and access to the same has been reported in U.S. studies in which only about half of the medical providers actually seem to adhere to the guidelines.9,19 Several limitations of this study should be noted. Response bias20,21 and reporter desirability may impact survey validity. Although familiarity with guidelines, beliefs, and attitudes about prescribing controller anti-inflammatory medications reports may be affected by response bias, it is less likely that the information obtained pertaining to the strategies used in prescribing controller anti-inflammatory medications and the barriers relating to pharmacological treatment would be impacted by social desirability. Bias could also be introduced if responders differ systematically from nonresponders. This is especially important when response rates are low. Our study had a response rate of 63% similar to average response rates obtained in studies that use mail surveys and above average to response rates obtained in other mail surveys of physicians.20,21

Conclusions and Recommendations

Our survey showed that most pediatricians in Puerto Rico are familiarized with the asthma treatment guidelines, have positive attitudes toward the prescription of controller medications (CMs), and are concerned with the lack of resources for providing preventive care. Yet, these same pediatricians perceived significant financial and resource barriers for providing optimal medication and prevention treatment for children with public insurance who have persistent asthma. Pediatricians also reported that other important barriers to providing optimal treatment were related to the family's poor adherence to follow-up visits and to poor family management. These observations are consonant with our view that the causes of asthma disparities are multiple, complex, and inter-related.22 If asthma disparities in Puerto Rico are to be reduced, then a better understanding of the complex ways in which multiple variables related to the health-care system policies, socioeconomic factors, family and provider factors, as well as the relative weight that each one contributes to the inequalities observed is needed.

Nevertheless, a number of recommendations can be made that can ameliorate the treatment disparities observed in the island and the barriers faced by pediatricians. Asthma cannot be controlled effectively unless patients have access to a full range of services and quality of care to all patients. The current health policy makes it difficult for pediatricians and other providers to deliver high-quality care. This policy needs to be revised so that primary care providers do not feel jeopardized by prescribing CMs to patients with persistent asthma. Provider training in knowledge and implementation of treatment guidelines is also essential if more children are to be properly treated. Finally, resources are needed for pediatricians who practice with children from the public sector so that they can provide the appropriate preventive interventions. Families need to be educated on the importance of follow-up visits and how to manage properly their child's asthma.

Appendix

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the following investigators for their collaboration and providing consultant support: María M. Alvarez, M.D., Angel L. Colón-Semidey, M.D., Federico Montealegre, Ph.D., and José R. Rodríguez-Santana, M.D., and Dr. Mary Helen Mays for editing this article.

Financial Support

This study was supported by NIH Grant 5P60 MD002261-02 funded by the National Center for Minority Health and Health Disparities. In addition, it was supported for technical assistance by the UPR School of Medicine Endowed Health Services Research Center, Grants 5S21MD000242 and 5S21MD000138, from the National Center for Minority Health and Health Disparities, National Institutes of Health (NCMHD-NIH). The contents of this article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of NCMHD-NIH.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA, 2006) Global strategy for asthma management and prevention. Updated 2008. www.ginasthma.org www.ginasthma.org

- 2.National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. National Asthma Education and Prevention Program. Expert Panel Report 3: Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of asthma. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health; 2007. Full Report 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barnes NC. Marone G. Di Maria GU. Visser S. Utama I. Payne SL. A comparison of fluticasone propionate, 1 mg daily, with beclomethasone dipropionate, 2 mg daily, in the treatment of severe asthma. International Study Group. Eur Respir J. 1993;6:877–885. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Suissa S. Assimes T. Brassard P. Ernst P. Inhaled corticosteroid use in asthma and the prevention of myocardial infarction. Am J Med. 2003;115:377–381. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(03)00393-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Halterman JS. Yoos HL. Kaczorowski JM. McConnochie K. Holzhauer RJ. Conn KM, et al. Providers underestimate symptom severity among urban children with asthma. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156:141–146. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.156.2.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sawicki GS. Smith L. Bokhour B. Gay C. Hohman KH. Galbraith AA, et al. Periodic use of inhaled steroids in children with mild persistent asthma: what are pediatricians recommending? Clin Pediatr. 2008;47:446–451. doi: 10.1177/0009922807312184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Finkelstein JA. Lozano P. Farber HJ. Miroshnik I. Lieu TA. Underuse of controller medications among Medicaid-insured children with asthma. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156:562–567. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.156.6.562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lozano P. Grothaus LC. Finkelstein JA. Hecht J. Farber HJ. Lieu TA. Variability in asthma care and services for low-income populations among practice sites in managed Medicaid systems. Health Serv Res. 2003;38(6 Pt 1):1563–1578. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2003.00193.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cabana M. Rand C. Becher O. Rubin H. Reasons for pediatrician nonadherance to asthma guidelines. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2001;155:1057–1062. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.155.9.1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Diette GB. Patino CM. Merriman B. Paulin L. Riekert K. Okelo S, et al. Patient factors that physicians use to assign asthma treatment. Arch Int Med. 2007;167:1360–1366. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.13.1360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hillman AL. Ripley K. Goldfarb N. Weiner J. Nuamah I. Lusk E. The use of physician financial incentives and feedback to improve pediatric preventive care in Medicaid managed care. Pediatrics. 1999;104(4 Pt 1):931–935. doi: 10.1542/peds.104.4.931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vila D. Rand CS. Cabana MD. Quiñones A. Otero M. Gamache C. García P. Canino G. Medication reimbursement policy and asthma medication use: the case of pediatric asthma in Puerto Rico. J Asthma. doi: 10.3109/02770903.2010.517338. [in press]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Allen FC. Vargas PA. Kolodner K. Eggleston P. Butz A. Huss K, et al. Assessing pediatric clinical asthma practices and perceptions: a new instrument. J Asthma. 2000;37:31–42. doi: 10.3109/02770900009055426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cabana MD. Slish KK. Evans D. Mellins RB. Brown RW. Lin X, et al. Impact of physician asthma care education on patient outcomes. Pediatrics. 2006;117:2149–2157. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.SAS Institute Inc. SAS for Windows, Version 9.1.3. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc.; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 16.McQuaid EL. Vasquez J. Canino G. Fritz GK. Ortega AN. Colon A. Klein RB. Kopel SJ. Koinis-Mitchell D. Esteban CA. Seifer R. Beliefs and barriers to medication use in parents of latino children with asthma. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2009;44:892–898. doi: 10.1002/ppul.21074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Flores G. Abreu M. Schwartz I. Hill M. The importance of language and culture in pediatric care: case studies from the Latino community. J Pediatr. 2000;137:842–848. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2000.109150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Flores G. Lee M. Bauchner H. Kaster B. Pediatricians' attitudes, beliefs, and practices regarding clinical practice guidelines: a national survey. Pediatrics. 2000;105:496–501. doi: 10.1542/peds.105.3.496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cabana M. Abu-Isa H. Thyne S. Yawn B. Specialty differences in prescribing inhaled corticosteroids for children. Clin Pediatr. 2007;46:698–705. doi: 10.1177/0009922807301436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Asch D. Jedrziewski M. Christakis N. Response rates to mail surveys published in medical journals. J Clin Epidemiol. 1997;50:1129–1136. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(97)00126-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cummings S. Savitz L. Konrad T. Reported response rates to mailed physician questionnaires. Health Serv Res. 2001;35:1347–1355. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Canino G. McQuaid EL. Rand CS. Addressing asthma health disparities: a multilevel challenge. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;123:1209–1217. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.02.043. quiz 18–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]