Abstract

Psoriasis is a multifactorial skin disease characterized by epidermal hyperproliferation and chronic inflammation, the most common form of which is psoriasis vulgaris (PsV). We present a genome-wide association analysis of 2,339,118 SNPs in 472 psoriasis patients and 1,146 controls from Germany, with follow-up of the 147 most significant SNPs in 2,746 PsV cases and 4,140 controls from three independent replication panels. We identified an association at TRAF3IP2 on 6q21 and genotyped two SNPs at this locus in two additional replication panels (the combined discovery and replication panels consisted of 6,487 cases and 8,037 controls; combinded P = 2.36×10−10 for rs13210247 and combined P = 1.24×10−16 for rs33980500). About 15% of psoriasis cases develope psoriatic arthritis (PsA). A stratified analysis of our datasets including only PsA cases (1,922 cases compared to 8,037 controls, P=4.57×10−12 for rs33980500) suggested that TRAF3IP2 represents a shared susceptibility for PsV and PsA. TRAF3IP2 encodes a protein involved in IL-17 signaling and which interacts with memebers of the Rel/NF-κB transcription factor family.

Psoriasis (MIM 177900) is a chronic immune-mediated and hyperproliferative disorder of the skin that affects up to 3% of individual in populations of European ancestry1–3. The most common form, PsV, is characterized by red, raised, scaly plaques that commonly occur on the elbows, knees, scalp and lower back4.

Disease concordance in monozygotic twin pairs amounts to at most 70%5 and the sibling recurrence risk, λs, of PsV has been estimated to range between 4 and 115,6. Part of the genetic susceptibility can be explained by the established susceptibility locus at PSORS1 in the human leucocyte antigen (HLA) complex on chromosome 6p21.3 (HLA-C) as well as polymorphisms at the IL12B7, IL23R8–11, IL4/IL1312, IL23A, TNIP1 and TNFAIP313 loci. Because these susceptibility loci only account for a λs of less than 1.3513, a large fraction of the heritability for PsV remains unexplained. In addition, a deletion of two LCE cluster genes has been proposed to be a risk factor for the development of psoriasis, implying that structural variants could also contribute to the overall disease susceptibility14.

To identify additional PsV susceptibility loci, we performed genome-wide SNP genotyping of 487 German PsV cases and 1161 controls (screening panel A, Supplementary Table 1) using the Illumina HumanHap 550k array. For genotype imputation with phased HapMap data as a reference and subsequent statistical analysis, we used a data set that passed stringent quality control filters. This cleaned data set consisted of 504,742 autosomal SNPs genotyped in 472 cases and 1146 controls. Imputation served to considerably increase the genomic coverage of our study to a total number of 2,339,118 SNPs. Conservatively accounting for multiple testing by Bonferroni correction, the threshold for genome-wide significance was P≤2.14×10−8 in the imputed data set. A moderate genomic control value of λGC=1.065 indicated a minimal overall inflation of the test statistics due to population stratification. Furthermore, the multidimensional scaling analysis showed genuine European ancestry of panel A and identity-by-state analysis revealed neither non-European “outliers” nor cryptically related individuals after quality control (Supplementary Fig. 1). Our screening panel A had 80% power to detect a variant with an odds ratio of 1.38 or higher at the 5% significance level, assuming a frequency of the disease-associated allele of at least 30% in controls.

The initial comparison of case-control frequencies confirmed the association of PsV with the established susceptibility loci at HLA-C (rs12191877, P=4.21×10−32, OR=2.79, 95% CI=2.35–3.33) and IL12B (rs2546890, P=8.83×10−8, OR=0.65, 95% CI=0.56–0.76). Suggestive evidence for association was found for IL23R (rs1004819, P=6.17×10−4, OR=1.33, 95% CI=1.13–1.57) and on 1q21, 22 kb upstream of LCE3C (rs4112788, P=6.36×10−4, OR=0.76, 95% CI=0.64–0.89) (see Supplementary Fig. 2). The lead SNPs rs2546890 and rs1004819 were in moderate linkage disequilibrium (LD) (r2>0.50) with the previously described associated variants at the IL12B (rs7709212)9,15 and IL23R (rs2201841)13 loci, respectively. To identify novel susceptibility loci, we excluded all SNPs within the extended HLA complex (chromosome 6p21 at 25–34 Mb) and visually inspected the cluster plots of all index SNPs with a P value less than 0.001 after the clumping procedure. The 180 most strongly associated SNPs were subsequently selected for replication analysis and genotyped in the German replication panel B (681 cases, 1824 controls). After quality control, we excluded 33 follow-up SNPs.

In addition, an in silico replication was performed using available genome-wide association study (GWAS) datasets for panel C from the United States (1,303 cases and 1,322 controls; Collaborative Association Study of Psoriasis (CASP))13 and for panel D form Canada (762 cases and 994 controls; S.D., J.V.R., M.B., H.F. and C.R., unpublished data). We imputed both datasets, that is, the CASP dataset, which was genotyped by Perlegen Sciences, and the Canadian dataset, which was generated using the Illumina Human 1M BeadChip, were imputed. Of the 147 SNPs genotyped in panel B, we obtained genotypes for 126 SNPs in panel C and for 144 SNPs in panel D. Detailed association results including genotype counts of the 147 SNPs are given in Supplementary Table 2.

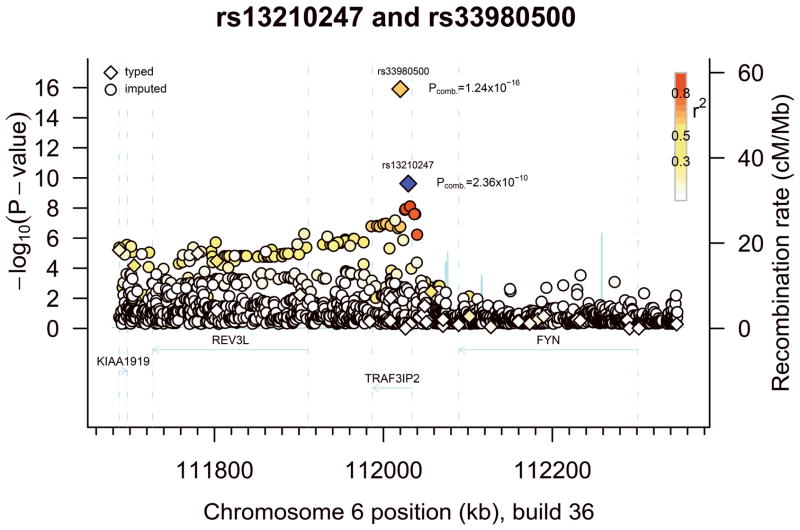

Two SNPs upstream of IL12B, included as a positive control for our experiment, achieved genome-wide significance in the combined replication panels B through D (rs2546890: replication stage P=9.07×10−15; rs953861: replication stage P=6.50×10−14). A previously unidentified association in the combined analysis of the three replication panels was obtained for SNP rs13210247 (replication stage P=6.25×10−6, risk allele frequency for cases = 0.09, risk allele frequency for controls = 0.07) with association robust to Bonferroni correction (corrected significance threshold of α=3.4×10−4, calculated as 0.05/147). This intronic SNP is located in the TRAF3IP2 gene, which encodes the TRAF3 interacting protein 2, and which is also known as ACT1, the NF- κB activator 1 protein. In the combined panels A to D, consisting of a total of 3218 PsV cases and 5286 controls, this SNP achieved genome-wide significance (Pcomb.=7.31×10−9) (Fig. 1). We observed suggestive evidence for association for four other SNPs; however, these associations did not remain significant after Bonferroni correcting for multiple testing. These four SNPs are located in RYR2 (rs2485558, replication stage P=0.01, combined P=1.53×10−5), in DPP6 (rs916514, replication stage P=0.0496, combined P=6.03×10−4), in MMP27 (rs1939015, replication stage P =0.026, combined P=7.09×10−4) and 31 kb downstream of NFκBIA (rs2145623, replication stage P=2.29×10−3, combined P =5.01×10−6), respectively (Table 1).

Figure 1. Regional plot of TRAF3IP2.

Regional plot of the negative decadic logarithm of the combined P values from the imputed panels A, C and D in a ~700 kb window around the intronic lead SNP rs13210247 (blue filled diamond) and the missense SNP rs33980500 (r2=0.63). Panels A, C and D were imputed with CEU haplotypes generated by the 1000 Genomes Project (August 2009 release) as a reference. The intronic SNP rs13210247 and the missense SNP rs33980500 were genotyped in the replication panels, and the combined P values of panels A through F are indicated for both SNPs (Table 2). The magnitude of linkage disequilibrium (LD) with the central SNP rs13210247, measured by r2, is reflected by the color of each SNP symbol (for color coding, see upper right corner of each plot). Recombination activity (cM/Mb) is depicted by a blue line.

Table 1. Summary of association results.

We analyzed the top 147 SNPs of the GWAS (including typed and imputed genotypes) in three independent PsV case-control panels (B through D). Data is shown for the seven SNPs that were nominal significant in the combined replication analysis of panels B through D (replication stage P<0.05, highlighted in bold) with consistent direction of effects in panel A and B. The number of cases and controls of each panel is shown in the top column. Results of all 147 SNPs are shown in Supplementary Table 2. SNPs are ranked according to their P value obtained in the GWAS. Nucleotide positions refer to NCBI build 36. Chr., chromosome. A1 denotes the minor allele and A2 is the common allele. Allele frequencies of A1 are shown (AFA1). The P value, the odds ratio (OR) and the 95% CI for carriership of the minor allele A1 are shown for the genome-wide association analysis (panel A). The combined P value of the meta-analysis is shown for the independent replication panels B through D (Prepl.) as well as for the GWAS panel together with the independent replication panels (panels A through D; Pcomb.). rs13210247 was additionally tested in replication panels E and F. Results for this SNP in panels B through F (replication; 6,015 cases and 6,891 controls) and panels A through F (GWAS and replication; 6,487 cases and 8,037 controls) are provided in the main text and in Table 2.

| Panel A – GWAS Germany 472 cases 1146 controls |

Panel B Germany 681cases 1824 controls |

Panel C CASP 1303 cases 1322 controls |

Panel D Genizon 762 cases 994 controls |

Panel B – D (replication only) Combined analysis 2746 cases 4140 controls |

Panel A – D (GWAS & replication) Combined analysis 3218 cases 5286 controls |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chr Pos. (bp) |

dbSNP ID | Nearby genes (relative position) |

A1 A2 |

AFA1 Case |

AFA1 Control |

P-value | OR (95% CI) |

AFA1 Case |

AFA1 Control |

AFA1 Case |

AFA1 Control |

AFA1 Case |

AFA1 Control |

Prepl. | Pcomb. |

| 5 158,692,478 |

rs2546890 | IL12B (−2.5 kb) | G A |

0.36 | 0.46 | 8.83×10−08 | 0.65 (0.56–0.76) | 0.38 | 0.44 | 0.42 | 0.49 | 0.45 | 0.53 | 9.07×10−15 | 1.29×10−20 |

| 1 235,345,148 |

rs2485558 | RYR2 (intronic) | G C |

0.31 | 0.24 | 2.81×10−06 | 1.49 (1.26–1.76) | 0.24 | 0.23 | 0.23 | 0.21 | 0.26 | 0.24 | 0.01 | 1.53×10−05 |

| 5 158,705,160 |

rs953861 | IL12B (−15 kb) | G A |

0.23 | 0.17 | 1.60×10−05 | 1.51 (1.25–1.82) | 0.22 | 0.18 | 0.22 | 0.17 | 0.21 | 0.14 | 6.50×10−14 | 6.21×10−18 |

| 14 34,908,987 |

rs2145623 | NFKBIA (+31 kb) | C G |

0.34 | 0.27 | 3.01×10−05 | 1.41 (1.2–1.66) | 0.33 | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.28 | 0.28 | 0.26 | 2.29×10−03 | 5.01×10−06 |

| 6 112,029,413 |

rs13210247 | TRAF3IP2 (intronic) | G A |

0.10 | 0.06 | 8.17×10−05 | 1.7 (1.3–2.22) | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 6.25×10−06 | 7.31×10−09 |

| 7 154,099,909 |

rs916514 | DPP6 (intronic) | G A |

0.09 | 0.14 | 1.37×10−04 | 0.61 (0.47–0.79) | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.10 | 0.09 | 0.0496 | 6.03×10−04 |

| 11 102,081,585 |

rs1939015 | MMP27 (missense) | G A |

0.12 | 0.16 | 1.56×10−03 | 0.69 (0.55–0.87) | 0.14 | 0.14 | 0.15 | 0.17 | 0.17 | 0.20 | 0.026 | 7.09×10−04 |

We also confirmed the previously reported association of PsV and the LCE3C-LCE3B deletion14 at P=3.80×10−5 (for details on genotyping and copy number analyses see Online Methods).

To further validate the newly associated PsV susceptibility gene TRAF3IP2, we genotyped the lead SNP, rs13210247, in the two additional case-control panels E (1,987 cases and 1,661 controls from Michigan) and F (1,282 cases and 1,090 controls from Canada). The combined replication panels B through F comprised 6,015 PsV cases and 6,891 healthy controls, yielding a replication P value of 1.00×10−7 with the same direction of effect for all five panels (combined P value for panels A through F=2.36×10−10).

We additionally selected all validated coding SNPs within the TRAF3IP2 gene from NCBI’s dbSNP16 build 130 (rs1043730, rs13190932 and rs33980500) for genotyping in replication panel B. Of the existing three missense SNPs, only rs33980500, located in exon 2, showed a significant association (P=0.0265, OR=1.28, 95% CI=1.03–1.58). Therefore, this SNP was also genotyped in the replication panels C through F. Association analysis of the obtained replication cohort (panel B through F) yielded a highly significant P value of 8.00×10−14 (combined P value for panels A through F=1.24×10−16) (Table 2). Because the missense SNP was not available from the HapMap II CEU imputation reference, we performed imputation based on CEU haplotypes generated by the 1000 Genomes project for panels A, C and D in order to fine map a region of 700 kb around TRAF3IP2 containing 1,935 SNPs (Fig. 1). The intronic TRAF3IP2 SNP rs13210247 and the missense SNP rs33980500 are about 9.5 kb apart and are in moderate LD (LD in panels A to F; r2=0.63). We performed a logistic regression analysis to test for the independence of these two markers. When conditioning for the missense SNP rs33980500, the intronic SNP rs13210247 was not significantly associated with disease (P=0.709). In the reverse comparison, the missense SNP rs33980500 remained significantly associated (P=3.77×10−7), indicating that it can account for the association at the TRAF3IP2 gene locus. In a subset of German cases and controls (993 cases and 2,277 controls from panels A and B) for which HLA-Cw6 status was available, we tested for the presence of a statistical interaction between HLA-Cw6 carriership and rs33980500 genotypes but found no statistical support for interaction (P=0.77).

Table 2. Summary of association results for the two TRAF3IP2 SNPs genotyped in additional replication panels.

The lead SNP rs13210247 and the missense SNP rs33980500 were genotyped in five independent PsV case-control panels (B through F, Supplementary Table 1). The number of cases and controls of each panel is shown in the top column. Nucleotide positions refer to NCBI build 36. Chr., chromosome. A1 denotes the rare allele and A2 is the common allele. Allele frequencies of A1 are shown (AFA1). The combined P value of the meta-analysis is shown for the independent replication panels B to F (Prepl.) as well as for the GWAS panel together with the independent replication panels (panels A through F; Pcomb.).

| Panel A Germany 472cases 1146 controls |

Panel B Germany 681cases 1824 controls |

Panel C CASP 1303 cases 1322 controls |

Panel D Genizon 762 cases 994 controls |

Panel E Michigan 1987 cases 1661 controls |

Panel F Canada 1282 cases 1090 controls |

Panel B – F (replication only) Combined analysis 6015 cases 6891 controls |

Panel A – F (GWAS & replication) Combined analysis 6487 cases 8037 controls |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chr Pos. (bp) |

dbSNP ID | Nearby genes (relative position) |

A1 A2 |

AFA1 Case |

AFA1 Control |

AFA1 Case |

AFA1 Control |

AFA1 Case |

AFA1 Control |

AFA1 Case |

AFA1 Control |

AFA1 Case |

AFA1 Control |

AFA1 Case |

AFA1 Control |

Prepl. | Pcomb. |

| 6 112,029,413 |

rs13210247 | TRAF3IP2 (intronic) | G A |

0.10 | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 1.00×10−07 | 2.36×10−10 |

| 6 112,019,955 |

rs33980500 | TRAF3IP2 (missense) | T C |

0.10 | 0.06 | 0.10 | 0.08 | 0.11 | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.11 | 0.08 | 0.11 | 0.07 | 8.00×10−14 | 1.24×10−16 |

The missense SNP rs33980500 (Asp19Asn) causes a mutation from aspartic acid to asparagine in the protein sequence and the resulting change in charge (a negative electric charge to nonpolar) might have an impact on the protein structure and, hence, its function. Additionally, the mutation is located in a region that is more than 90% conserved among different species (Supplementary Fig. 3), which further implies a possible functional consequence of this change.

Furthermore, we performed in silico analyses and found a putative TRAF6-binding peptide (amino acids 13 to 21) containing the SNP Asp19Asn. This peptide is similar to a known TRAF6-binding motif of CD40, a member of the tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily17. Notably, the mutation of the accordant seventh peptide residue (asparagine to aspartate) has previously been observed to change the binding affinity of TRAF6 to CD40 significantly18. Therefore, rs33980500 may also affect the interaction of TRAF3IP2 to TRAFs and, thus, the involved inflammatory pathways.

About 15% of individuals with psoriasis develop psoriatic arthritis (PsA), which is an inflammatory, disabling arthrits2,19. This suggests that PsV and PsA share common susceptibility factors. To determine the association of the TRAF3IP2 missense SNP with PsA, we performed a PsA stratified analysis of panel A through F. Association analysis of all PsA patients and controls within our combined sample (1,919 cases and 8,037 controls) yielded a P value of 4.57×10−12 for rs33980500 (OR=1.57, CI=1.38–1.78). In an equally sized subgroup of randomly extracted PsV cases without PsA, we obtained a P value of 2.04×10−6 (OR=1.37, CI=1.20–1.57). The overlap in confidence intervals for the two associations, along with the fact that no significant difference was obtained when comparing the 1,919 PsA cases versus the randomly selected 1,919 PsV cases suggests that the TRAF3IP2 gene locus represents a shared susceptibility locus for PsA and PsV.

Gene expression of psoriatic and uninvolved skin differs significantly for hundreds of genes that are involved in immune response or in the regulation of cellular differentiation and proliferation20. To check if altered gene activity might trigger disease progression, we examined expression levels of several loci in biopsies from 57 healthy controls and compared these to expression levels of biopsies of involved and uninvolved skin from 53 PsV cases (subgroup of panel C). We analyzed the TRAF3IP2 locus and some genes that potentially act downstream of TRAF3IP2. For the TRAF3IP2 locus, the expression level was slightly altered between involved and uninvolved skin (P=2.2×10−3) (Supplementary Fig. 4). However, the dosage of risk alleles at the according SNPs did not correlate with transcript levels for the genes in involved, uninvolved or normal skin (Supplementary Table 3).

Genetic variants in the TRAF3IP2 locus are implicated in PsV and PsA susceptibility for the first time, to our knowledge, by our study. The gene product of TRAF3IP2 is a positive signaling adaptor required for IL-17-mediated T-cell immune responses21. The TRAF3IP2 protein interacts with tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor (TRAF) proteins and either I-κB kinase or mitogen-activated protein kinase to activate either NF-κB or Jun kinase. Upon recruitment to CD40 and the BAFF receptor in B-cells, TRAF3IP2 also negatively regulates B-cell survival through its interaction with TRAF322. The negative regulation of CD40-BAFF-mediated B cell functions results in ‘hyper-T cell-dependent’ and T cell-independent immune responses in TRAF3IP2-deficient mice. Researchers in a previous study also found that TRAF3IP2 is a key component of IL-17-mediated signaling and that IL-17-mediated gene expression is completely abolished in TRAF3IP2-deficient mouse embryonic fibroblasts. In addition, epithelial cells could be identified as the critical cell type in which TRAF3IP2 mediates IL-17-dependent inflammatory disease21. In PsV, a subset of T-cells expressing IL-17 plays a major role23. The IL-17 expressing T-cells that are abundant in the epidermis of psoriatic lesions but which are absent in healthy donor epidermis are CD8+ cells, whereas in lesional psoriatic dermis, mainly IL-17 expressing CD4+ (but also CD8+) T-cells are strongly increased relative to healthy skin. Epidermal hyperplasia and the production of innate immune peptides such as human β-defensin 2 (hBD-2) are associated with these IL-17+ T-cells24. The crucial role of IL-17 is also supported by the observation that in psoriasis treatment response to TNF inhibitors correlates with suppressed IL-17 signaling25. Moreover, we showed that in immortalized N-TERT keratinocytes (N-TERT KCs) and in normal human keratinocytes (NHKs) IL-17A and TNF-α together induce the expression of DEFB4 (encoding hBD-2) which is absent in N-TERT KCs and NHKs with silenced TRAF3IP2 (see Supplementary Fig. 5). In epithelial cells, the binding of IL-17A and/or IL-17F to the heterodimeric IL-17R leads to the recruitment of TRAF3IP2 through homotypic interactions between conserved (SEFIR) domains. This allows the incorporation of TRAF6 into the signaling complex and then downstream activation of the NF-κB and mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways26. We thus speculate that a dysregulation of TRAF3IP2 might have a major impact on IL-17 signaling and, hence, on the activation of NFκB-pathways, leading to the upregulation of pro-inflammatory factors.

For the TRAF3IP2 locus newly identified here, fine mapping and resequencing efforts together with extensive functional studies are required to detect all potential causal variants and thus to specify the contribution of the locus to overall disease susceptibility.

Online Methods

Recruitment of patients and healthy controls

Samples were organized in panels that corresponded to the successive steps of the present study. All individual panels (A–F) were independent from each other. All German patients of panels A and B were recruited either at the Department of Dermatology of the Christian-Albrechts-University Kiel or the Department of Dermatology and Allergy of the Technical University Munich through local outpatient services. Individuals were considered to be affected if chronic plaque or guttate psoriasis lesions covered more than 1% of the total body surface area or if at least two skin, scalp, nail or joint lesions were clinically diagnosed of psoriasis. Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) was diagnosed by clinical finding of joint complaints and radiologic and rheumatologic confirmation by criteria according to Moll and Wright27, or more recently to the Classification Criteria for Psoriatic Arthritis (CASPAR)28.

2510 German healthy control individuals of panel A and B were obtained from the popgen biobank29. 483 German healthy controls were selected from the KORA S4 survey, an independent population-based sample from the general population living in the region of Augsburg, southern Germany30.

The American study population (panel C) consisted of 1303 psoriasis cases and 1322 controls after quality control. The data sets used for the analyses described in this manuscript were obtained from the database of Genotype and Phenotype (dbGaP). The genotyping of samples was provided through the Genetic Association Information Network (GAIN). Samples and associated phenotype data were provided by the “Collaborative Association Study of Psoriasis” (CASP). Funding support for CASP was provided by the National Institutes of Health, the Foundation for NIH’s Genetic Association Information Network and the National Psoriasis Foundation.

The Canadian population sample used for panel D consisted of 762 psoriasis patients and 994 controls, sampled from the Québec founder population (QFP). Membership in the QFP was defined as having four grandparents with French-Canadian family names who were born in the Province of Québec, Canada, or in adjacent areas of the Provinces of New Brunswick and Ontario or in New England or New York State. This criterion assures that all subjects were descendant from French-Canadians living before the 1960s, after which time admixture with non-French-Canadians became more common.

For replication of the two TRAF3IP2 SNPs (rs13210247 and rs33980500), panel E was tested in addition for an association. This panel comprised 1987 psoriasis cases and 1661 controls of European ancestry. The sample was collected at the University of Michigan and selection criteria for cases included a requirement of at least two psoriatic plaques or a single plaque occupying >1% of total body surface area outside scalp. Individuals that presented only palmoplantar psoriasis, inverse psoriasis or sebopsoriasis were excluded. Individuals used as controls were older than 18 years, had no history of psoriasis and no family history of psoriasis.

Panel F, also used only for replication of the two TRAF3IP2 SNPs, consisted of 1282 psoriasis cases and 1090 controls from Toronto and Newfoundland, Canada. Psoriasis was diagnosed by a dermatologist. Control individuals showed no evidence of psoriasis, rheumatoid arthritis or other auto-immune disorders.

Written, informed consent was obtained from all study participants and all protocols were approved by the respective institutional ethical review committees of the participating centres.

SNP genotyping for genome-wide screen

The genotyping for the GWAS - which was part of the German GWAS initiative funded by the National Genome Research Network (NGFN) - was performed by Illumina’s service facility (San Diego, CA, USA) using the Illumina HumanHap 550k v1 with 561,466 SNP markers (San Diego, CA, USA). All experimental steps were carried out according to standard protocols.

We excluded 5 samples with more than 10% missing genotypes (i.e. call rate <90%). Individuals who showed statistically relevant genetic dissimilarity to the other subjects (population outliers), or who showed evidence for cryptic relatedness to other study participants (unexpected duplicates, first- or second-degree relatives) were removed (Supplementary Fig. 1). These quality control measures left 472 psoriasis samples and 1146 control samples for inclusion in screening panel A. All gender assignments could be verified by reference to the proportion of heterozygous SNPs on the X chromosome. Before analysis we excluded 56,724 markers (10% of all SNPs) that had a low genotype call rate (<95% in cases or controls; n=4,254), were monomorphic or rare (minor allele frequency <2% in cases or controls; n=30,862), deviated from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) in the control sample (PHWE<0.01; n=7,600), or that were non-autosomal SNPs (n=14,008).

Imputation

Genotype imputation was performed using a hidden Markov model algorithm implemented in the software program MACH v.1.0.1631 to infer missing genotypes in silico. As a reference, HapMap II CEU phased haplotypes32 were used.

As input for the imputation only genotyped SNPs that passed quality control were used. Of the imputed SNPs we analyzed only these SNPs which could be imputed with a relatively high confidence (estimated r2 between imputed SNP and true genotypes ≥0.8), had a minor allele frequency >2% in cases or controls and a HWE P-value <0.01 in the control sample. To take imputation uncertainty into account, we used allelic dosage association as implemented in the program MACH2DAT31. The allelic dosage is the weighted sum of the genotype class probabilities.

SNP selection for replication

SNPs of the genome-wide scan that passed quality control were analyzed using gPLINK v2.049 in combination with PLINK v1.0533. The SNP list (including imputed and genotyped SNPs) was pruned for redundancy due to linkage disequilibrium by using the --clump command of PLINK. For all genotyped index SNPs with a P-value <10−3, a visual inspection of the cluster plots was performed. SNPs that did not pass the visual inspection were excluded from further analyses. The 180 most strongly associated index SNPs of the clumps (P<2.6×10−4) were ordered as genotyping assays. If the genotyping assay design was not possible for a SNP, the next best SNP from the clump was chosen for the assay design.

SNPlex and TaqMan genotyping

The ligation-based SNPlex™ genotyping system and functionally tested TaqMan® SNP Genotyping Assays (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) were used to genotype variants in replication panel B. For technical replication of the results of the two TRAF3IP2 SNPs, TaqMan® SNP Genotyping Assays were used in panels A-E while the Sequenom Platform was used for panel F.

Of 180 selected SNPs 147 SNPs passed quality control. These SNPs had a high call rate (>90% in cases or controls; 25 SNPs were removed), were not monomorphic (minor allele frequency >1% in cases or controls; 2 SNPs were removed), and did not deviate from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) in the control population (PHWE>0.0001; 5 SNPs were removed). One SNP failed genotyping and was excluded from the analysis.

CNV genotyping and quality control

The functionally tested TaqMan® Copy Number Assays Hs 02550639_cn (in LCE3C) and Hs 02878369_cn (in LCE3B) (Applied Biosystems) were used to genotype copy number variation within the late cornified envelope (LCE) gene cluster in samples of panel A and B (754 cases and 1052 controls). Genotyping was carried out according to Applied Biosystems standard protocols with 5ng of dried DNA per well.

All cases were genotyped thrice and all control samples were genotyped four times. The generated data was analyzed with the analysis software CopyCaller™ v1.0. The analysis settings were selected as recommended by the CopyCaller™ Software User Guide. The chosen confidence threshold of the associated predicted copy number was ≥95%. Control samples were removed when more than one of the four measurements did not pass quality control whereas cases were removed when one of the three measurements did not pass quality control. Altogether, 736 cases and 932 controls remained for association analysis (94% of all samples).

Statistical analyses

Power calculations were carried out using PS Power and Sample Size v3.0.1234. GWAS data were analyzed using R statistical environment version 2.10.0 and gPLINK v2.049 in combination with PLINK v1.0533. The --clump command was used to reduce the number of SNPs for follow-up by removing correlated hit SNPs. The meta-analysis of the different panels was performed with METAL.

TRAF3IP2 silencing in keratinocytes

Small hairpin RNA (shRNA) targeting enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) was cloned into the pLenti4/Block-iT-DEST (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) as previously described35. ShRNA lentiviral constructs directed against TRAF3IP2 were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Lentiviral particles were produced in 293FT cells and used to infect immortalized N-TERT keratinocytes (kindly provided by Dr. James Rheinwald) and normal human keratinocytes (NHK) at 10–20% percent confluence as previously described36. After 72 h of infection the cells were incubated in basal medium and stimulated for 30 h with IL17 (10 ng/ml), IL22 (10 ng/ml) and/or TNF-α (20 ng/ml). Total RNA was isolated using RNeasy Mini Kits with on-column DNAse digestion according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and reversed transcribed using the High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Real-time PCR analysis for DEFB4, TRAF3IP2 and the control gene RPLP0 (ribosomal protein P0) was performed using pre-validated TaqMan gene expression assays from Applied Biosystems according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Target gene expression was normalized to the control gene RPLP0 and mRNA levels were expressed as percent of RPLP0.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank all individuals with psoriasis, their families and physicians for their cooperation. We acknowledge the cooperation of Genizon Biosciences. We wish to thank Tanja Wesse, Tanja Henke, Catharina Fürstenau, Susan Ehlers, Meike Davids and Rainer Vogler for expert technical help. This study was supported by the German Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) through the National Genome Research Network (NGFN), the Popgen biobank, and the KORA research platform (KORA: Cooperative Research in the Region of Augsburg) KORA was initiated and financed by the Helmholtz Zentrum München-National Research Center for Environmental Health, which is funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education, Science, Research and Technology and by the State of Bavaria and the Munich Center of Health Sciences (MC Health) as part of LMUinnovativ. The project received infrastructure support through the DFG cluster of excellence “Inflammation at Interfaces”. This research was also supported by grants R01-AR42742, R01-AR050511 and R01-AR054966 from the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Author contributions

E.E. performed SNP selection, genotyping, data analysis and prepared figures and tables. A.F. helped with data analysis. D.E. performed the imputation and generated the regional association plots. P.E.S., J.G., J.D. and Y.L. performed the expression and eQTL analyses. S.W.S. and S.L performed shRNA experiments. G.A. helped with statistical analyses and interpretation of the results. M.A. and G.M. performed in silico protein analyses. M.W., U.M., S.W., B.E. and M.K. coordinated the recruitment and collected phenotype data of panels A and B.C.G. and H.E.W. provided the KORA control samples. J.T.E., J.J.V., R.P.N., T.T., S.D., J.V.R., M.B., H.F., C.R., P.R. and D.D.G. provided the replication samples C to F and respective genotypes and phenotypes. T.H.K. R.P.N. and D.K. helped with genotyping. D.E., M.W., J.T.E., T.H.K. and S.S. edited the manuscript and A.F. planned and supervised the study. E.E. and A.F. drafted the manuscript and all authors approved the final draft.

Competing financial interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Accession codes

The CASP GWAS data set (panel C) is deposited in dbGaP under the accession code phs000019.v1.p1.

URLs

METAL software: http://www.sph.umich.edu/csg/abecasis/Metal/

dbGAP: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gap/

NGFN Funding, press release 04-26-2007: http://www.ngfn.de/englisch/index_368.htm

MACH software: http://www.sph.umich.edu/csg/abecasis/mach/

HapMap data: http://hapmap.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/downloads/phasing/2006-07_phaseII/phased/

MACH2DAT software: http://www.sph.umich.edu/csg/abecasis/mach/)

PLINK v1.05: http://pngu.mgh.harvard.edu/~purcell/plink/

R statistical environment version 2.10.0: http://www.r-project.org/

References

- 1.Griffiths CE, Barker JN. Pathogenesis and clinical features of psoriasis. Lancet. 2007;370:263–71. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61128-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bowcock AM, Barker JN. Genetics of psoriasis: the potential impact on new therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:S51–6. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(03)01135-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gottlieb AB. Psoriasis: emerging therapeutic strategies. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2005;4:19–34. doi: 10.1038/nrd1607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oudot T, et al. An association study of 22 candidate genes in psoriasis families reveals shared genetic factors with other autoimmune and skin disorders. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:2637–45. doi: 10.1038/jid.2009.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bhalerao J, Bowcock AM. The genetics of psoriasis: a complex disorder of the skin and immune system. Hum Mol Genet. 1998;7:1537–45. doi: 10.1093/hmg/7.10.1537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elder JT, et al. The genetics of psoriasis. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:216–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tsunemi Y, et al. Interleukin-12 p40 gene (IL12B) 3[prime]-untranslated region polymorphism is associated with susceptibility to atopic dermatitis and psoriasis vulgaris. J Dermatol Sci. 2002;30:161–166. doi: 10.1016/s0923-1811(02)00072-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cargill M, et al. A large-scale genetic association study confirms IL12B and leads to the identification of IL23R as psoriasis-risk genes. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;80:273–90. doi: 10.1086/511051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Capon F, et al. Sequence variants in the genes for the interleukin-23 receptor (IL23R) and its ligand (IL12B) confer protection against psoriasis. Hum Genet. 2007;122:201–206. doi: 10.1007/s00439-007-0397-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nair RP, et al. Polymorphisms of the IL12B and IL23R genes are associated with psoriasis. J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128:1653–61. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5701255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu Y, et al. A genome-wide association study of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis identifies new disease loci. PLoS Genet. 2008;4:e1000041. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chang M, et al. Variants in the 5q31 cytokine gene cluster are associated with psoriasis. Genes Immun. 2008;9:176–81. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6364451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nair RP, et al. Genome-wide scan reveals association of psoriasis with IL-23 and NF-kappaB pathways. Nat Genet. 2009;41:199–204. doi: 10.1038/ng.311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Cid R, et al. Deletion of the late cornified envelope LCE3B and LCE3C genes as a susceptibility factor for psoriasis. Nat Genet. 2009;41:211–5. doi: 10.1038/ng.313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang XJ, et al. Polymorphisms in interleukin-15 gene on chromosome 4q31.2 are associated with psoriasis vulgaris in Chinese population. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127:2544–51. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sherry ST, et al. dbSNP: the NCBI database of genetic variation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:308–11. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.1.308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ye H, et al. Distinct molecular mechanism for initiating TRAF6 signalling. Nature. 2002;418:443–7. doi: 10.1038/nature00888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Darnay BG, Ni J, Moore PA, Aggarwal BB. Activation of NF-kappaB by RANK requires tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor (TRAF) 6 and NF-kappaB-inducing kinase. Identification of a novel TRAF6 interaction motif. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:7724–31. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.12.7724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gelfand JM, et al. Epidemiology of psoriatic arthritis in the population of the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:573. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2005.03.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhou X, et al. Novel mechanisms of T-cell and dendritic cell activation revealed by profiling of psoriasis on the 63,100-element oligonucleotide array. Physiol Genomics. 2003;13:69–78. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00157.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Qian Y, et al. The adaptor Act1 is required for interleukin 17-dependent signaling associated with autoimmune and inflammatory disease. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:247–56. doi: 10.1038/ni1439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Qian Y, et al. Act1, a negative regulator in CD40- and BAFF-mediated B cell survival. Immunity. 2004;21:575–87. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lowes MA, et al. Psoriasis vulgaris lesions contain discrete populations of Th1 and Th17 T cells. J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128:1207–11. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5701213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kryczek I, et al. Induction of IL-17+ T cell trafficking and development by IFN-gamma: mechanism and pathological relevance in psoriasis. J Immunol. 2008;181:4733–41. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.7.4733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zaba LC, et al. Effective treatment of psoriasis with etanercept is linked to suppression of IL-17 signaling, not immediate response TNF genes. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;124:1022–10. e1–395. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.08.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hunter CA. Act1-ivating IL-17 inflammation. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:232–4. doi: 10.1038/ni0307-232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moll JM, Wright V. Psoriatic arthritis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1973;3:55–78. doi: 10.1016/0049-0172(73)90035-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Taylor W, et al. Classification criteria for psoriatic arthritis: development of new criteria from a large international study. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:2665–73. doi: 10.1002/art.21972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Krawczak M, et al. PopGen: population-based recruitment of patients and controls for the analysis of complex genotype-phenotype relationships. Community Genet. 2006;9:55–61. doi: 10.1159/000090694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wichmann HE, Gieger C, Illig T. KORA-gen--resource for population genetics, controls and a broad spectrum of disease phenotypes. Gesundheitswesen. 2005;67 (Suppl 1):S26–30. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-858226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li Y, Willer C, Sanna S, Abecasis G. Genotype imputation. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2009;10:387–406. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.9.081307.164242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.The International HapMap Consortium. A second generation human haplotype map of over 3.1 million SNPs. Nature. 2007;449:851–61. doi: 10.1038/nature06258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Purcell S, et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:559–75. doi: 10.1086/519795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dupont WD, Plummer WD. PS power and sample size program available for free on the Internet. Controlled Clin Trials. 1997;18 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stoll SW, Johnson JL, Li Y, Rittie L, Elder JT. J Invest Dermatol. Amphiregulin Carboxy-Terminal Domain Is Required for Autocrine Keratinocyte Growth. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stoll SW, et al. Metalloproteinase-mediated, context-dependent function of amphiregulin and HB-EGF in human keratinocytes and skin. J Invest Dermatol. 130:295–304. doi: 10.1038/jid.2009.211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.