Abstract

Centesimal dilutions (5, 9 and 15 cH) of Gelsemium sempervirens are claimed to be capable of exerting anxiolytic and analgesic effects. However, basic results supporting this assertion are rare, and the mechanism of action of G. sempervirens is completely unknown. To clarify the point, we performed a comparative analysis of the effects of dilutions 5, 9 and 15 cH of G. sempervirens or gelsemine (the major active principle of G. sempervirens) on allopregnanolone (3α,5α-THP) production in the rat limbic system (hippocampus and amygdala or H-A) and spinal cord (SC). Indeed, H-A and SC are two pivotal structures controlling, respectively, anxiety and pain that are also modulated by the neurosteroid 3α,5α-THP. At the dilution 5 cH, both G. sempervirens and gelsemine stimulated [3H]progesterone conversion into [3H]3α,5α-THP by H-A and SC slices, and the stimulatory effect was fully (100%) reproducible in all assays. The dilution 9 cH of G. sempervirens or gelsemine also stimulated 3α,5α-THP formation in H-A and SC but the reproducibility rate decreased to 75%. At 15 cH of G. sempervirens or gelsemine, no effect was observed on 3α,5α-THP neosynthesis in H-A and SC slices. The stimulatory action of G. sempervirens and gelsemine (5 cH) on 3α,5α-THP production was blocked by strychnine, the selective antagonist of glycine receptors. Altogether, these results, which constitute the first basic demonstration of cellular effects of G. sempervirens, also offer interesting possibilities for the improvement of G. sempervirens-based therapeutic strategies.

1. Introduction

Neurons and glial cells are capable of synthesizing various bioactive steroids also called neurosteroids, which can regulate the nervous system activity via autocrine or paracrine mechanisms [1–4]. Pharmacological and behavioral studies have suggested that neurosteroids are involved in the regulation of important neurobiological mechanisms [1, 5–7]. In particular, the neurosteroid 3α,5α-tetrahydroprogesterone (3α,5α-THP), also named allopregnanolone, plays a key role in the modulation of neurological and psychopathologic symptoms such as depression, anxiety, analgesia and neurodegeneration [8–13]. 3α,5α-THP is a potent activator of the central inhibitory transmission, which acts through allosteric sites located on γ-amino butyric acid type A (GABAA) receptor [10, 14] or on strychnine-sensitive glycine receptor (Gly-R) [15, 16]. Because 3α,5α-THP endogenously synthesized in the central nervous system significantly modulates anxiety or nociceptive mechanisms through paracrine and autocrine modes [17–22], substances which are capable of stimulating 3α,5α-THP formation in neural networks appear as potentially interesting for the development of effective anxiolytic or analgesic therapies [23–30]. However, to be therapeutically effective, the candidate substances must be devoid of side effects such as nausea, vomiting tolerance, dependence or breathing failure induced by certain anxiolytics and analgesics [31–34].

For several years, preparations from the yellow jasmine or Gelsemium sempervirens Loganacea have been claimed to be anxiolytic and analgesic medicines but, surprisingly, scientific results from basic research supporting this assertion are extremely rare. Indeed, except two studies which showed that G. sempervirens preparations may prevent stress or development of spontaneous seizures in vivo [35, 36], there are no fundamental evidence demonstrating that G. sempervirens may control neurophysiological processes such anxiety and pain. In particular, the cellular and pharmacological mechanisms of action of G. sempervirens are completely unknown. In our endeavor to clarify this situation, we have recently investigated the cellular effects of gelsemine, the major active principle in G. sempervirens composition, and we observed that gelsemine stimulated dose-dependently 3α,5α-THP secretion in the rat spinal cord (SC) through activation of Gly-R [37]. To gain more insights into the cellular and pharmacological mechanisms of action of G. sempervirens itself, we have now combined pulse-chase experiments, high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) and flow scintillation detection [19, 22, 38–42] to perform a comparative analysis of the effects of G. sempervirens and gelsemine preparations on [3H]progesterone conversion into [3H]3α,5α-THP in the rat limbic system (hippocampus and amygdala or H-A) and SC. Indeed, the limbic system and SC are well-known for their crucial roles in the modulation of anxiety and pain, respectively [43–49]. We have also characterized pharmacologically, the main receptor involved in the mediation of G. sempervirens cellular effects in the limbic system and SC.

2. Methods

2.1. Animals

Adult male Sprague-Dawley rats weighing 300–350 g were used in this study. Animal care and manipulations were performed according to the European Community Council Directives (86/609/EC) and under the supervision of authorized investigators. All experiments were performed minimizing the number of animals used and their suffering in accordance with the Alsace Department of Veterinary Public Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (Agreement number: 67-186). The animals were obtained from a commercial source (Janvier, France) and housed under standard laboratory conditions in a 12-h light/dark cycle with food and water ad libitum.

2.2. Chemicals and Reagents

Dichloromethane (DCM), propylene glycol and strychnine hydrochloride were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, USA). Hexane and isopropanol were obtained from Fischer Bioblock Scientific (Illkirch, France). The synthesis product gelsemine came from Extrasynthese (Genay, France). Sodium chloride (NaCl) was purchased from VWR Prolabo (Fontenay-sous-Bois, France). Synthetic steroids including PROG, 5α-dihydroprogesterone (5α-DHP) and 3α,5α-THP were obtained from Steraloids (Newport, USA). Tritiated steroids such as 1,2,6,7-3H(N)-progesterone ([3H]PROG) and 9,11,12-3H(N)-3α,5α-tetrahydroprogesterone ([3H]3α,5α-THP) were supplied by PerkinElmer (Boston, USA).

2.3. Preparation of Gelsemine and G. sempervirens Dilutions

By using a conventional dilution process (pharmacological dilutions from a stock solution of 1 M of gelsemine), we have recently observed that gelsemine at 10−10 M stimulated 3α,5α-THP production in the rat SC [37]. Therefore, we decided to check whether or not gelsemine preparations obtained by homeopathic procedure (dilutions/dynamizations) may conserve the ability to stimulate 3α,5α-THP formation. Then, we asked Boiron Laboratories to prepare homeopathic dilutions of gelsemine starting from a hydroalcoholic solution (30% ethanol, v/v) of synthetic gelsemine (purchased from Extrasynthese, Genay France) at 1 M. Homeopathic dilutions/dynamizations were performed in cascade with de-ionized water. Consequently, the homeopathic dilutions 5, 9 and 15 cH led theoretically to gelsemine solution at 10−10, 10−18 and 10−30 M, respectively.

Gelsemium sempervirens preparations were obtained using the same homeopathic procedure but the mother tincture was a hydroalcoholic (30% ethanol, v/v) extract of G. sempervirens plant roots. Gelsemine quantity in G. sempervirens mother tincture was determined by using a quantitative HPLC method [50, 51]. Briefly, 20 μl of G. sempervirens mother tincture was analyzed on the HPLC column, using a butylamine/water/methanol (0.1 : 22 : 78 v/v/v) gradient. Synthetic gelsemine (20 μl), used as reference standard, was chromatographed under the same conditions and its elution position as well as the retention time of gelsemine present in G. sempervirens solution were determined by ultraviolet absorption at 255 nm. The amount of gelsemine contained in G. sempervirens was calculated considering areas of the peaks corresponding to synthetic gelsemine and gelsemine eluted from G. sempervirens solution. The concentration of gelsemine estimated from the analyses of different samples of G. sempervirens mother tinctures varied between 5 × 10−3 and 5 × 10−4 M.

After each dilution step, all gelsemine or G. sempervirens solutions were agitated at high speed. Control solutions were prepared according to the same procedure described above, using only the hydroalcoholic solution (30% ethanol, v/v), which was submitted to the dilution/dynamization cascade with de-ionized water. All gelsemine and G. sempervirens preparations as well as control solutions were kept at 4°C before use. Because the dilutions 5, 9 and 15 cH of G. sempervirens are often used for homeopathic treatments in humans [52], we decided in agreement with the company Boiron to focus our efforts on a detailed comparative analysis of the effects of these three dilutions of gelsemine and G. sempervirens on allopregnanolone production in H-A and SC.

2.4. Pulse-Chase Experiments

For each experiment, 200 mg SC (lumbar segment) or 15 mg H-A slices were preincubated for 15 min in 1.5 ml of 0.9% NaCl at 37°C. The SC and H-A were dissected in rats after deep anesthesia. The SC was removed by hydraulic extrusion and slices were made in the lumbar region. SC and H-A slices were incubated at 37°C for 3 h with 1.5 ml of 0.9% NaCl (pH 7.4) containing 50 nM [3H]PROG supplemented with 1% propylene glycol in the presence of tested compounds. The incubation was carried out in a water-saturated atmosphere (95% air, 5% CO2), which made it possible to maintain the pH at 7.4. At the end of the incubation period, the reaction was stopped by adding 500 μl of ice-cold 0.9% NaCl and transferring the incubation medium in tubes into a cold water bath (0°C). Newly-synthesized neurosteroids released in the incubation medium were extracted three times with 2 ml of DCM, and the organic phase was evaporated on ice under a stream of nitrogen. The dry extracts were redissolved in 2 ml of hexane and prepurified on Sep-Pak C18 cartridges (Waters Associates, Milford, USA). Steroids were eluted with a solution made of 50% isopropanol and 50% hexane. The solvent was evaporated in a RC-10-10 Speed Vac Concentrator and the dry extracts were kept at −20°C until HPLC analysis. The extraction efficiency was 89 ± 7%.

2.5. HPLC-Flo/One Characterization of Steroids

The newly synthesized steroids extracted from the incubation medium already purified on Sep-Pak cartridges were characterized using a previously validated method which combines HPLC analysis and flow scintillation detection [19, 22, 38–42]. Briefly, the prepurified extracts were analyzed by reversed-phase HPLC on a liquid chromatograph (322 pump, UV/VIS 156 detector, Unipoint system; Gilson, Middleton, USA) equipped with a 4.6 × 250 mm SymetryShield C18 column (Waters Associates, Milford, USA) equilibrated with 100% hexane. The radioactive steroids were eluted at a flow rate of 0.5 ml min −1 using a gradient of isopropanol (0%–60% over 65 min) including five isocratic steps at 0% (0–10 min), 1% (30–35 min), 2% (40–45 min), 30% (50–55 min) and 60% (60–65 min). The tritiated steroids eluted from the HPLC column were directly quantified with a flow scintillation analyzer (Radiomatic Flo/One-Beta A 500; Packard Instruments, Meriden, USA) equipped with a Pentium IV PC computer (Dell-Computer-France, Lyon, France) for measurement of the percentage of total radioactivity contained in each peak. Synthetic steroids used as reference standards were chromatographed under the same conditions as the extracts obtained from the incubation media and their elution positions were determined by ultraviolet absorption using a UV/VIS 156 detector (Gilson, Middleton, USA). The elution positions of steroids change on analytic columns after the purification of a certain number of tissue extracts. Therefore, to optimize the characterization of newly synthesized neurosteroids, synthetic tritiated neuroactive steroids including [3H]PROG and [3H]3α,5α-THP were also used as reference standards, chromatographed under the same conditions as the extracts and identified by their elution times with the Flo/One computer system before and after each extract analytic run.

2.6. Quantification of 3α,5α-THP Released by the SC and H-A Slices and Statistical Analysis

The amount of [3H]3α,5α-THP newly synthesized from [3H]PROG and released by H-A or SC slices in the incubation medium was expressed as a percentage of the total radioactivity contained in all peaks resolved by the HPLC-Flo/One system (after analysis of the incubation medium extracts), including [3H]PROG itself. Each value presented is the mean (±SEM) of four independent experiments. Statistical analysis was performed with the 3.05 version of GraphPad Instat (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). The statistical significance of differences between two groups was assessed with Student's t-test. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Bonferroni's test was applied for multi-parameter analyses. A P-value of less than 0.05 was considered significant.

3. Results

3.1. Effects of Gelsemine and G. sempervirens Preparations on 3α,5α-THP Production in the SC and H-A

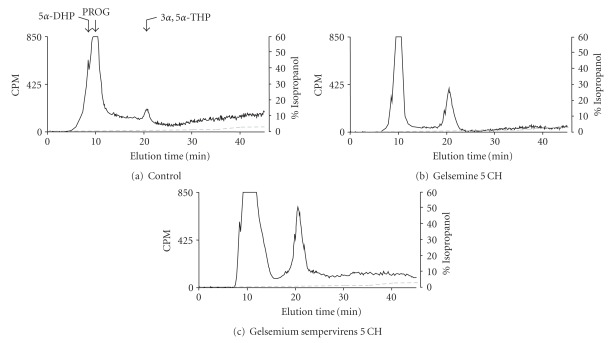

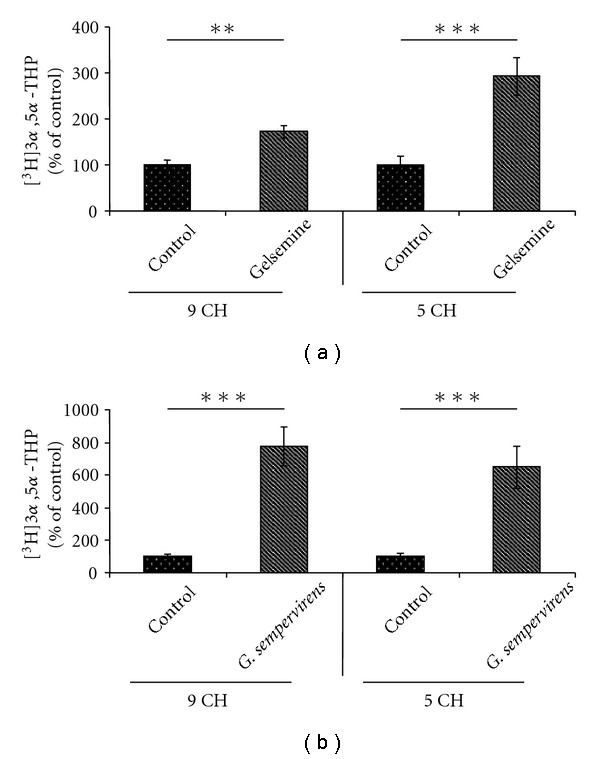

A 3-h incubation of lumbar SC slices with [3H]PROG yielded the formation of various radioactive metabolites (Figures 1(a)–1(c)). Reversed-phase HPLC analysis coupled with flow scintillation detection made it possible to resolve two major radioactive metabolites coeluting with [3H]5α-dihydroprogesterone ([3H]5α-DHP) and [3H]3α,5α-THP (Figures 1(a)–1(c)). The conversion of [3H]PROG into [3H]5α-DHP and [3H]3α,5α-THP was also observed in H-A (limbic system) slices with the same chromatographic profile as this shown in Figure 1. Investigations of the effects of gelsemine and G. sempervirens on [3H]3α,5α-THP neosynthesis in SC and H-A slices were performed by testing the dilutions 5, 9 and 15 cH. At the dilution 5 cH, gelsemine and G. sempervirens preparations were able to stimulate significantly [3H]progesterone conversion into [3H]3α,5α-THP in SC (Figure 2) and H-A (Figure 3). The stimulatory effect of geslmine or G. sempervirens at 5 cH was fully (100%) reproducible since the same effect was observed in all intra- and inter-assays performed. At the dilution 9 cH, a stimulatory action of gelsemine or G. sempervirens was detected on 3α,5α-THP production in SC and H-A slices (Figures 2 and 3] but this effect was observed only in 75% of the total number of samples in intra- and inter-assays investigations. No effect was detected when gelsemine and G. sempervirens preparations were applied at the dilution 15 cH. In the SC, G. sempervirens or gelsemine at 5 cH induced, respectively, a 547% or 193% increase of [3H]3α,5α-THP neosynthesis from [3H]progesterone (Figures 2(a) and 2(b)). In the limbic system or H-A, G. sempervirens or gelsemine at 5 cH generated, respectively, a 178% or 94% enhancement of [3H]3α,5α-THP formation (Figures 2(a) and 2(b)).

Figure 1.

Characterization of [3H]-neurosteroids released in the incubation medium by: (a) lumbar SC slices after a 3-h incubation with [3H]PROG in the absence (b) or in presence of gelsemine 5 cH or (c) Gelsemium sempervirens 5 cH. Analyses were performed using a hexane/isopropanol gradient and a reverse-HPLC system coupled to a flow scintillation detector. The ordinate indicates the radioactivity measured in the HPLC eluent. The dashed line represents the gradient of secondary solvent (% isopropanol). The arrows indicate elution positions of standard steroids.

Figure 2.

Effects of gelsemine (a) and G. sempervirens (b) at 9 or 5 cH on 3α,5α-THP production by SC slices. Each value was calculated as the relative amount of [3H]3α,5α-THP compared with the total [3H]-labeled compounds resolved by HPLC-Flo/One characterization (×100). The values were obtained from experiments similar to those presented in Figures 2(a). Results were then expressed as percentages of the amount of [3H]3α,5α-THP formed in absence of gelsemine or G. sempervirens (control). Each value is the mean (± SEM) of four independent experiments. **P < .01, ***P < .001 as compared to control (Student's t-test).

Figure fig3.

Effects of gelsemine (a) and G. sempervirens (b) at 9 or 5 cH on 3α,5α-THP production by H-A slices. The values were obtained from experiments similar to those presented in Figure 1. Results were then expressed as percentages of the amount of [3H]3α,5α-THP formed in the control group. Each value is the mean (±SEM) of four independent experiments. *P < .05, ***P < .001 as compared to control (Student's t-test).

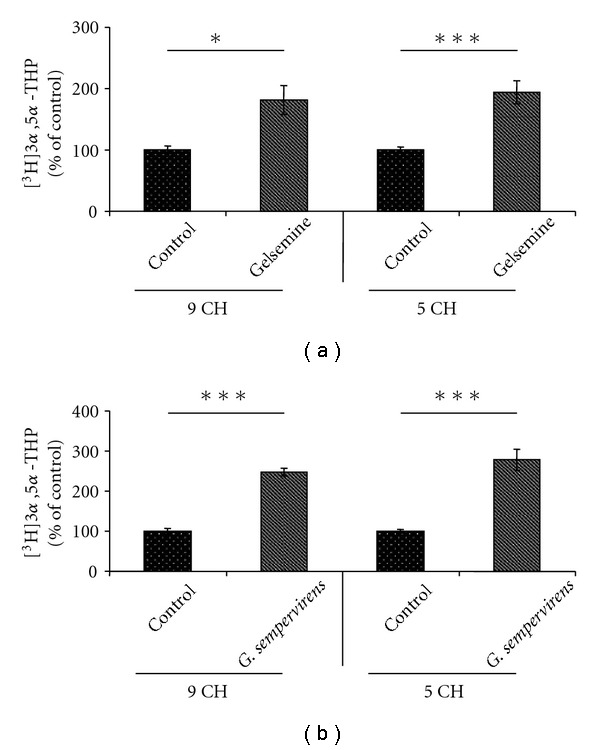

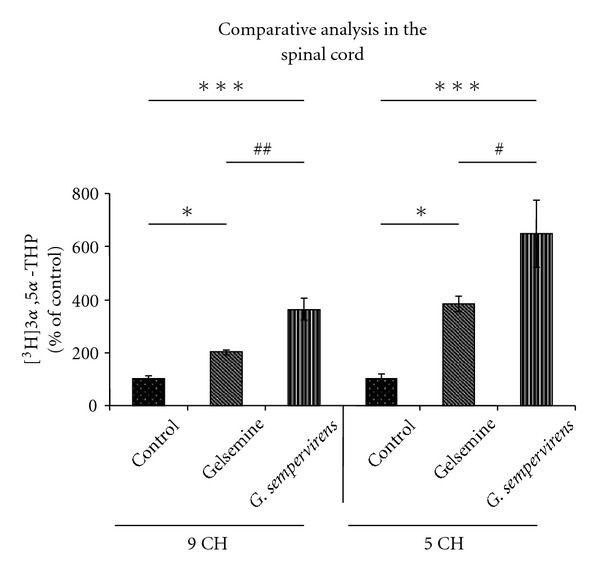

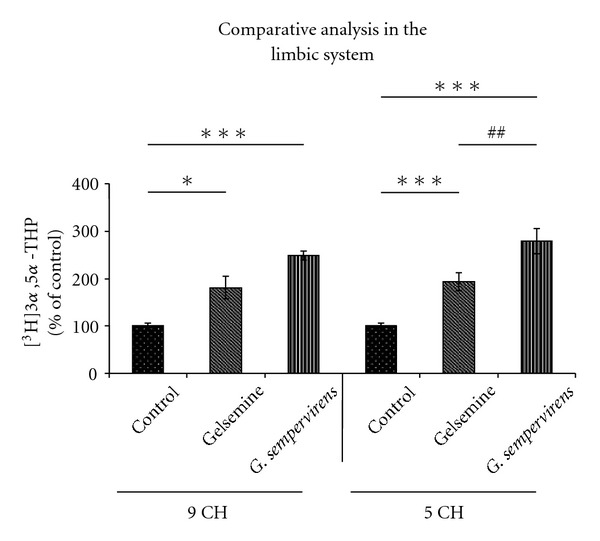

3.2. Comparative Analysis of the Stimulatory Capacity of Gelsemine and G. sempervirens on 3α,5α-THP Biosynthesis

In the SC, G. sempervirens preparations produced a stronger stimulation of 3α,5α-THP formation than gelsemine. Indeed, the level of [3H]3α,5α-THP newly synthesized in the presence of G. sempervirens at 5 cH was 1.7-fold higher than in the presence of gelsemine at 5 cH (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Comparative analysis of the effects of gelsemine and G. sempervirens at 9 or 5 cH on [3H]PROG conversion into [3H]3α,5α-THP by SC slices. The values were obtained from experiments similar to those presented in Figure 1. Results were then expressed as percentages of the amount of [3H]3α,5α-THP formed in the control group. Each value is the mean (±SEM) of four independent experiments. *P < .05, ***P < .001 as compared to control; # P < .05, ## P < .01 as compared to gelsemine (ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's test).

In the limbic system or H-A slices, G. sempervirens at 5 cH increased 3α,5α-THP production 1.5-fold than gelsemine at 5 cH (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Comparative analysis of the effects of gelsemine and G. sempervirens at 9 or 5 cH on [3H]PROG conversion into [3H]3α,5α-THP by H-A slices. The values were obtained from experiments similar to those presented in Figure 1. Results were then expressed as percentages of the amount of [3H]3α,5α-THP formed in absence of gelsemine and G. sempervirens (control). Each value is the mean (± SEM) of four independent experiments. *P < .05, ***P < .001 as compared to control; ## P < .01 as compared to gelsemine (ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's test).

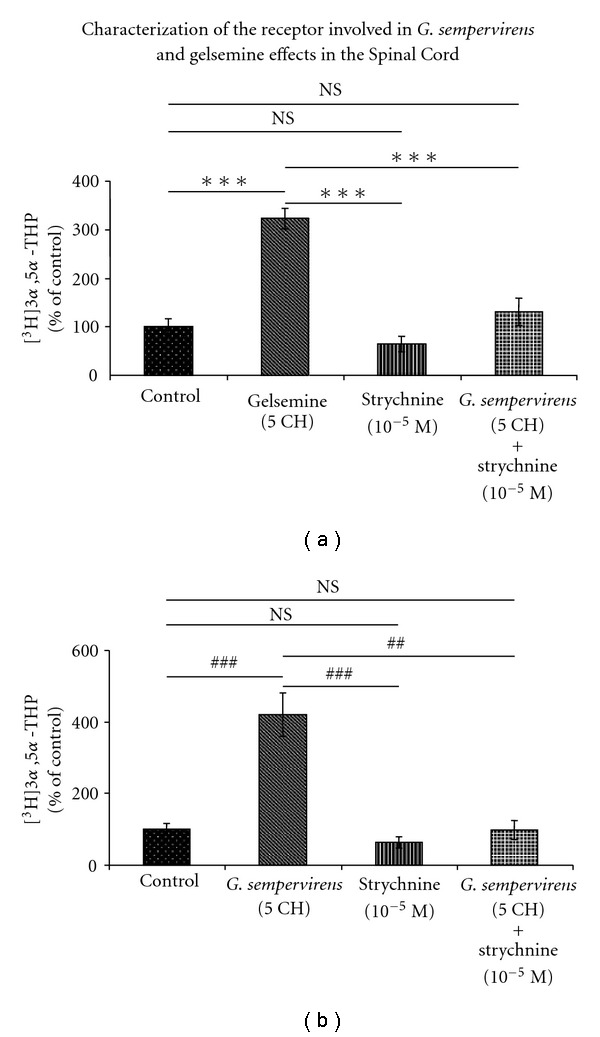

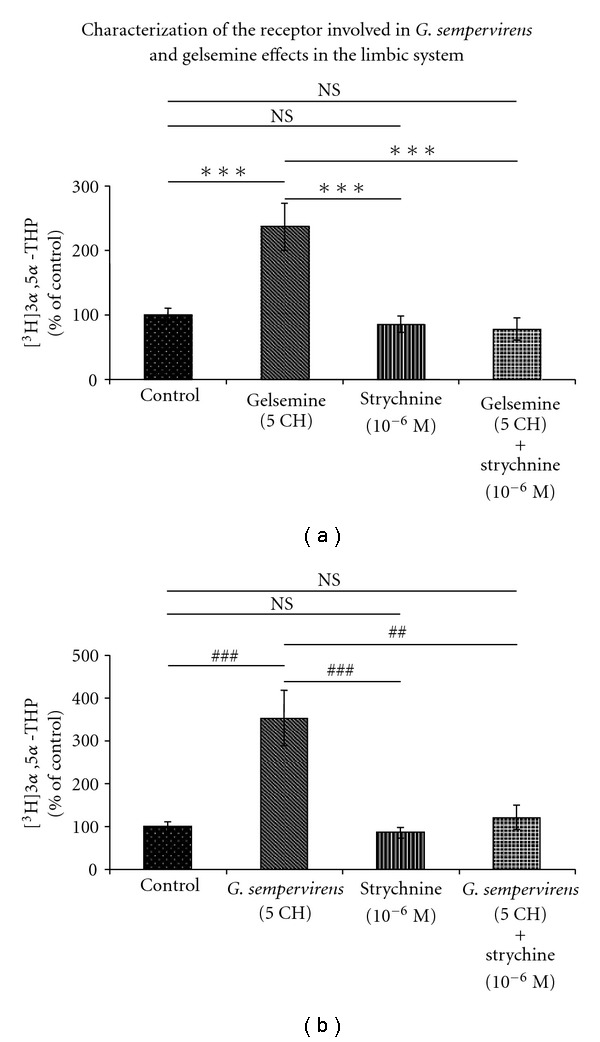

3.3. Pharmacological Characterization of the Receptor Mediating the Effects of Gelsemine and G. sempervirens Preparations on 3α,5α-THP Biosynthesis in the SC and H-A

On the basis of our previous observations about synthetic gelsemine [37], we investigated whether or not strychnine-sensitive Gly-R may be involved in the mediation of the effects of G. sempervirens and gelsemine preparations obtained by homeopathic procedure (Figures 6 and 7). In a first step, we performed pulse-chase/HPLC-Flo/One experiments in the presence of various concentrations of strychnine, the well-known selective antagonist of Gly-R; we observed that strychnine at 10−5 or 10−6 M was completely devoid of action on the formation of [3H]3α,5α-THP in the SC or H-A, respectively (Figures 6 and 7). In addition, we found that the stimulatory effect exerted by gelsemine (5 cH) or G. sempervirens (5 cH) on [3H]3α,5α-THP production in the SC was completely antagonized by strychnine at 10−5 M (Figures 6(a) and 6(b)). Similarly, in the limbic system or H-A slices, increase of [3H]3α,5α-THP neosynthesis induced by gelsemine (5 cH) or G. sempervirens (5 cH) was completely blocked by strychnine (10−6 M) (Figures 7(a) and 7(b)).

Figure 6.

Effects of gelsemine (a) or G. sempervirens (b) at 5 cH on [3H]3α,5α-THP production by SC slices in the absence or presence of strychnine (10−5 M), the specific glycine receptor antagonist. The values were obtained from experiments similar to those presented in Figure 1. Results were then expressed as percentages of the amount of [3H]3α,5α-THP formed in the control group. Each value is the mean (±SEM) of four independent experiments. ***P < .001 as compared to gelsemine; ## P < .01, ### P < .001 as compared to G. sempervirens (ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's test). NS represents not statistically different.

Figure 7.

Effects of (a) gelsemine or (b) G. sempervirens at 5 cH on 3α,5α-THP production by H-A slices in the absence or presence of strychnine (10−6 M). The values were obtained from experiments similar to those presented in Figure 1. Results were then expressed as percentages of the amount of [3H]3α,5α-THP formed in the control group. Each value is the mean (±SEM) of four independent experiments. ***P < .001 as compared to gelsemine; ## P < .01, ### P < .001 as compared to G. sempervirens (ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's test). NS represents not statistically different.

4. Discussion

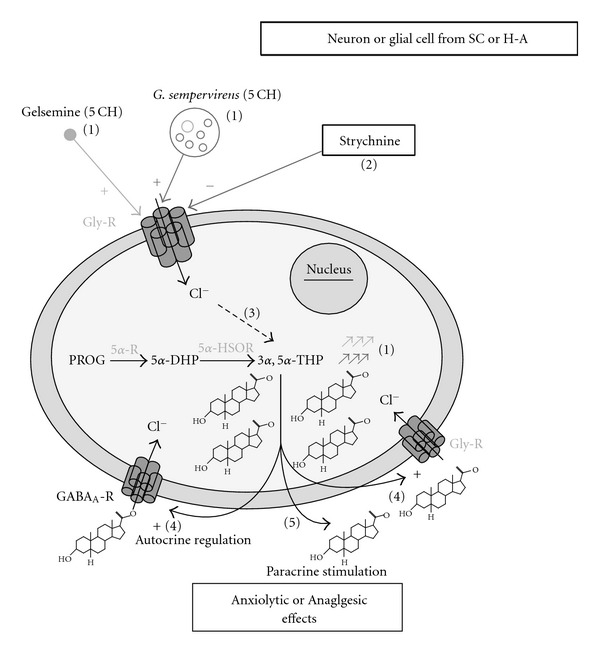

This article provides the first basic evidence supporting the existence of cellular effects of G. sempervirens preparations in the limbic system and SC. In addition, the work made possible the identification of pharmacological mechanisms involved in the mediation of G. sempervirens and gelsemine action in H-A and SC slices. Thanks to a well-validated approach combining pulse-chase experiments with HPLC analysis and continuous flow scintillation detection [19, 22, 38–42], we observed that gelsemine and G. sempervirens at 5 cH significantly stimulated [3H]progesterone conversion into [3H]3α,5α-THP in H-A (limbic system) and SC slices. At the dilution 9 cH, a stimulatory action of gelsemine and G. sempervirens was also detected on 3α,5α-THP production in the SC and H-A but the reproducibility rate was limited at 75%. This observation suggests the existence of instability or the lack of homogeneity of high diluted homeopathic solutions. In agreement with this hypothesis, there was no linearity of the stimulatory effects induced by gelsemine or G. sempervirens at 5 and 9 cH contrary to what is usually observed in conventional pharmacology for dose-response studies. Neurosteroid 3α,5α-THP possesses an important therapeutical potential owing to its key role in the regulation of cellular mechanisms involved in anxiety, pain, depression and neurodegeneration [4, 9, 10, 12, 13]. In particular, it has clearly been shown that the endogenous conversion of progesterone into 3α,5α-THP in the limbic system is crucial for the expression of anxiolytic effect of progesterone [9, 20, 21, 53]. Moreover, we have recently demonstrated that 3α,5α-THP endogenously synthesized in SC exerts a key analgesic action in animals subjected to sciatic nerve injury-induced neuropathic pain [18, 19]. Therefore, it appears that the stimulatory effect exerted by G. sempervirens or gelsemine preparations on 3α,5α-THP production in H-A or SC may reflect cellular mechanisms activated by these preparations to induce anxiolytic or analgesic effects. In support of this hypothesis, the presence and activity of 3α-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase or 3α-HSOR (the key enzyme synthesizing 3α,5α-THP) has been evidenced in the limbic system and spinal circuit, suggesting that G. sempervirens and gelsemine may increase 3α,5α-THP formation through stimulation of 3α-HSOR enzymatic activity in H-A and SC neural networks [18, 54–56]. Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that the limbic and spinal systems, two pivotal structures modulating respectively anxiety and pain sensation, contain several populations of nerve cells expressing Gly-R [43, 44, 46–48, 57–60]. Consistently, our pharmacological analyses revealed that strychnine, the selective antagonist of Gly-R [58, 59], completely blocked the stimulatory effect of gelsemine and G. sempervirens on 3α,5α-THP production in H-A and SC slices. Taken together, these results show that gelsemine (5 cH) and G. sempervirens (5 cH), acting through Gly-R located on H-A and SC nerve cells, may stimulate 3α-HSOR enzymatic activity, which, in turn, may increase 3α,5α-THP production in the limbic system and spinal circuit. Our data and hypothesis are summarized and illustrated by the general diagram presented in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Effect of gelsemine (5 cH) or G. sempervirens (5 cH) on 3α,5α-THP production in the SC and H-A. (1) Gelsemine (5 cH) or G. sempervirens (5 cH) stimulated [3H]progesterone conversion into [3H]3,5-THP in SC and H-A slices. (2) Strychnine, the selective antagonist of glycine receptors (Gly-R), totally blocked the stimulatory effect of gelsemine (5 cH) or G. sempervirens (5 cH) on 3α,5α-THP production. (3) Further investigations are required for the identification of intracellular mechanisms triggered by gelsemine (5 cH) or G. sempervirens (5 cH) from Gly-R. However, the stimulatory action exerted by gelsemine (5 cH) or G. sempervirens (5 cH) on 3α,5α-THP production suggests that the intracellular cascade activated by these substances may increase the activity of 3α-HSOR which is the key 3α,5α-THP-synthesizing enzyme. [4, 5] Neurosteroid 3α,5α-THP newly synthesized by neurons or glial cells in the SC or H-A may modulate GABAA-R or Gly-R through autocrine (4) or paracrine (5) mechanisms leading to analgesic and/or anxiolytic effects of G. sempervirens.

The comparative analyses also revealed that the stimulatory capacity of G. sempervirens on 3α,5α-THP biosynthesis in H-A and SC slices seems higher than that of gelsemine. Indeed, the theoretical estimation of gelsemine quantity in G. sempervirens mother tincture made after HPLC analysis showed that the tincture contains a concentration less than 1 M. Significant differences are observed between samples of mother tinctures but it appeared that the initial gelsemine concentration in G. sempervirens mother tincture may not be higher than 5 × 10−3 M. Additional analyses such as mass spectrometry quantification after HPLC or gaz chromatographic purification will certainly help in the future to determine the accurate concentration of gelsemine in G. sempervirens mother tincture. However, based on the estimation performed herein, gelsemine at 5 cH (prepared from synthetic gelsemine stock solution at 1 M) may correspond to 10−10 M while G. sempervirens at 5 cH (prepared from the mother tincture) may contain a concentration of gelsemine within 5 × 10−14 M and 5 × 10−13 M. Because G. sempervirens at 5 cH increased 3α,5α-THP production 1.5- to 1.7-fold than gelsemine at 5 cH, it is possible to speculate that a positive synergism exists between gelsemine and other constituents present in G. sempervirens composition such as sempervirine, gelsemicine and gelsenicine [61–63]. Whether all constituents of G. sempervirens also modulate Gly-R like gelsemine [37] remains a matter of speculation. Future investigations will answer this question even though pharmacological analyses described herein revealed that the stimulatory action of G. sempervirens (5 cH) was totally (not partially) blocked by strychnine.

At the dilution 9 cH, gelsemine and G. sempervirens exerted a stimulatory action on 3α,5α-THP production but the effect was not reproducible in all intra- and inter-assays performed. However, because the stimulatory effect was observed in 75% of the total number of samples analyzed, it appears that high dilutions of G. sempervirens may conserve interesting bioactivity. Therefore, it seems reasonable to expect only a few or no side effects from G. sempervirens-based therapeutical strategies. Indeed, even if the results obtained with the dilution 9 cH may not be exploitable because of the limited reproducibility, therapeutic strategies may be achieved with G. sempervirens at 5 cH which remains a very low concentration that exhibited a full (100%) reproducible effect on 3α,5α-THP production in SC and H-A.

In conclusion, the results provided herein may constitute key basic knowledge on cellular and pharmacological effects of G. sempervirens and gelsemine preparations. The data may also open new possibilities for the improvement of current therapeutical utilization of G. sempervirens which refers only to empirical knowledge but not to fundamental evidence supplied by basic research.

Funding

Laboratories BOIRON and Université de Strasbourg; Contrat CIFRE (no. 659/2005, CNRS-BOIRON) fellowship (to C.V.).

Acknowledgments

The authors convey special thanks to Dr Philippe Belon and also thank Adrien Lacaud for his technical assistance.

References

- 1.Baulieu EE, Robel P, Schumacher M. Contemporary Endocrinology. Totowa, NJ, USA: Humana Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mellon SH, Griffin LD. Neurosteroids: biochemistry and clinical significance. Trends in Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2002;13(1):35–43. doi: 10.1016/s1043-2760(01)00503-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mensah-Nyagan AG, Do-Rego J-L, Beaujean D, Luu-The V, Pelletier G, Vaudry H. Neurosteroids: expression of steroidogenic enzymes and regulation of steroid biosynthesis in the central nervous system. Pharmacological Reviews. 1999;51(1):63–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patte-Mensah C, Mensah-Nyagan AG. Peripheral neuropathy and neurosteroid formation in the central nervous system. Brain Research Reviews. 2008;57(2):454–459. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2007.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dubrovsky B. Neurosteroids, neuroactive steroids, and symptoms of affective disorders. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 2006;84(4):644–655. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2006.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Majewska MD. Neurosteroids: endogenous bimodal modulators of the GABAA receptor. Mechanism of action and physiological significance. Progress in Neurobiology. 1992;38:379–395. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(92)90025-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schumacher M, Robel P, Baulíeu E-E. Development and regeneration of the nervous system: a role for neurosteroids. Developmental Neuroscience. 1996;18(1-2):6–21. doi: 10.1159/000111391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Akwa Y, Purdy RH, Koob GF, Britton KT. The amygdala mediates the anxiolytic-like effect of the neurosteroid allopregnanolone in rat. Behavioural Brain Research. 1999;106(1-2):119–125. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(99)00101-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barbaccia ML, Serra M, Purdy RH, Biggio G. Stress and Neuroactive steroids. International Review of Neurobiology. 2001;46:243–272. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7742(01)46065-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Belelli D, Lambert JJ. Neurosteroids: endogenous regulators of the GABAA receptor. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2005;6(7):565–575. doi: 10.1038/nrn1703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Griffin LD, Gong W, Verot L, Mellon SH. Niemann-Pick type C disease involves disrupted neurosteroidogenesis and responds to allopregnanolone. Nature Medicine. 2004;10(7):704–711. doi: 10.1038/nm1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Patte-Mensah C, Kibaly C, Boudard D, et al. Neurogenic pain and steroid synthesis in the spinal cord. Journal of Molecular Neuroscience. 2006;28(1):17–32. doi: 10.1385/jmn:28:1:17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Uzunova V, Sampson L, Uzunov DP. Relevance of endogenous 3α-reduced neurosteroids to depression and antidepressant action. Psychopharmacology. 2006;186(3):351–361. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-0201-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hosie AM, Wilkins ME, da Silva HM, Smart TG. Endogenous neurosteroids regulate GABAA receptors through two discrete transmembrane sites. Nature. 2006;444:486–489. doi: 10.1038/nature05324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maksay G, Laube B, Betz H. Subunit-specific modulation of glycine receptors by neurosteroids. Neuropharmacology. 2001;41(3):369–376. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(01)00071-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jiang P, Yang C-X, Wang Y-T, Xu T-L. Mechanisms of modulation of pregnanolone on glycinergic response in cultured spinal dorsal horn neurons of rat. Neuroscience. 2006;141(4):2041–2050. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Agís-Balboa RC, Pinna G, Pibiri F, Kadriu B, Costa E, Guidotti A. Down-regulation of neurosteroid biosynthesis in corticolimbic circuits mediates social isolation-induced behavior in mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104(47):18736–18741. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709419104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meyer L, Venard C, Schaeffer V, Patte-Mensah C, Mensah-Nyagan AG. The biological activity of 3α-hydroxysteroid oxido-reductase in the spinal cord regulates thermal and mechanical pain thresholds after sciatic nerve injury. Neurobiology of Disease. 2008;30:30–41. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2007.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Patte-Mensah C, Li S, Mensah-Nyagan AG. Impact of neuropathic pain on the gene expression and activity of cytochrome P450side-chain-cleavage in sensory neural networks. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 2004;61(17):2274–2284. doi: 10.1007/s00018-004-4235-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frye CA, Walf AA. Changes in progesterone metabolites in the hippocampus can modulate open field and forced swim test behavior of proestrous rats. Hormones and Behavior. 2002;41(3):306–315. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.2002.1763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frye CA, Walf AA, Rhodes ME, Harney JP. Progesterone enhances motor, anxiolytic, analgesic, and antidepressive behavior of wild-type mice, but not those deficient in type 1 5α-reductase. Brain Research. 2004;1004:116–124. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Patte-Mensah C, Kibaly C, Mensah-Nyagan AG. Substance P inhibits progesterone conversion to neuroactive metabolites in spinal sensory circuit: a potential component of nociception. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102:9044–9049. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502968102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hirani K, Sharma AN, Jain NS, Ugale RR, Chopde CT. Evaluation of GABAergic neuroactive steroid 3α-hydroxy-5α- pregnane-20-one as a neurobiological substrate for the anti-anxiety effect of ethanol in rats. Psychopharmacology. 2005;180(2):267–278. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-2169-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Korneyev A, Costa E. Allopregnanolone (THP) mediates anesthetic effects of progesterone in rat brain. Hormones and Behavior. 1996;30(1):37–43. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.1996.0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mok WM, Herschkowitz S, Krieger NR. Evidence that 3α-hydroxy-5α-pregnan-20-one is the metabolite responsible for anesthesia induced by 5α-pregnanedione in the mouse. Neuroscience Letters. 1992;135:145–148. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(92)90423-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pinna G, Dong E, Matsumoto K, Costa E, Guidotti A. In socially isolated mice, the reversal of brain allopregnanolone down-regulation mediates the anti-aggressive action of fluoxetine. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003;100:2035–2040. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0337642100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reddy DS, Apanites LA. Anesthetic effects of progesterone are undiminished in progesterone receptor knockout mice. Brain Research. 2005;1033(1):96–101. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sanna E, Talani G, Busonero F, Pisu MG, Purdy RH, Serra M, et al. Brain steroidogenesis mediates ethanol modulation of GABAA receptor activity in rat hippocampus. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2004;24:6521–6530. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0075-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ugale RR, Sharma AN, Kokare DM, Hirani K, Subhedar NK, Chopde CT. Neurosteroid allopregnanolone mediates anxiolytic effect of etifoxine in rats. Brain Research. 2007;1184(1):193–201. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.09.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Verleye M, Akwa Y, Liere P, et al. The anxiolytic etifoxine activates the peripheral benzodiazepine receptor and increases the neurosteroid levels in rat brain. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 2005;82(4):712–720. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2005.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schwartz TL, Nihalani N. Tiagabine in anxiety disorders. Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy. 2006;7(14):1977–1987. doi: 10.1517/14656566.7.14.1977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Benyamin R, Trescot AM, Datta S, et al. Opioid complications and side effects. Pain Physician. 2008;11(2):S105–S120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van Dorp ELA, Morariu A, Dahan A. Morphine-6-glucuronide: potency and safety compared with morphine. Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy. 2008;9(11):1955–1961. doi: 10.1517/14656566.9.11.1955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Papakostas GI. Tolerability of modern antidepressants. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2008;69:8–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bousta D, Soulimani R, Jarmouni I, et al. Neurotropic, immunological and gastric effects of low doses of Atropa belladonna L., Gelsemium sempervirens L. and Poumon histamine in stressed mice. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2001;74(3):205–215. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(00)00346-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Peredery O, Persinger MA. Herbal treatment following post-seizure induction in rat by lithium pilocarpine: Scutellaria lateriflora (Skullcap), Gelsemium sempervirens (Gelsemium) and Datura stramonium (Jimson Weed) may prevent development of spontaneous seizures. Phytotherapy Research. 2004;18(9):700–705. doi: 10.1002/ptr.1511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Venard C, Boujedaini N, Belon P, Mensah-Nyagan AG, Patte-Mensah C. Regulation of neurosteroid allopregnanolone biosynthesis in the rat spinal cord by glycine and the alkaloidal analogs strychnine and gelsemine. Neuroscience. 2008;153(1):154–161. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kibaly C, Patte-Mensah C, Mensah-Nyagan AG. Molecular and neurochemical evidence for the biosynthesis of dehydroepiandrosterone in the adult rat spinal cord. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2005;93(5):1220–1230. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03113.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kibaly C, Meyer L, Patte-Mensah C, Mensah-Nyagan AG. Biochemical and functional evidence for the control of pain mechanisms by dehydroepiandrosterone endogenously synthesized in the spinal cord. FASEB Journal. 2008;22(1):93–104. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-8930com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schaeffer V, Patte-Mensah C, Eckert A, Mensah-Nyagan AG. Modulation of neurosteroid production in human neuroblastoma cells by Alzheimer’s disease key proteins. Journal of Neurobiology. 2006;66(8):868–881. doi: 10.1002/neu.20267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schaeffer V, Meyer L, Patte-Mensah C, Eckert A, Mensah-Nyagan AG. Dose-dependent and sequence-sensitive effects of amyloid-β peptide on neurosteroidogenesis in human neuroblastoma cells. Neurochemistry International. 2008;52(6):948–955. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2008.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schaeffer V, Patte-Mensah C, Eckert A, Mensah-Nyagan AG. Selective regulation of neurosteroid biosynthesis in human neuroblastoma cells under hydrogen peroxide-induced oxidative stress condition. Neuroscience. 2008;151:758–770. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bannerman DM, Rawlins JNP, McHugh SB, et al. Regional dissociations within the hippocampus—memory and anxiety. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2004;28(3):273–283. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2004.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bremner JD. Alterations in brain structure and function associated with post-traumatic stress disorder. Seminars in clinical neuropsychiatry. 1999;4(4):249–255. doi: 10.153/SCNP00400249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Davis M. The role of the amygdala in fear and anxiety. Annual Review of Neuroscience. 1992;15:353–375. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.15.030192.002033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Haines DE, Mihailoff GA, Yezierski RP. The spinal cord. In: Haines DE, editor. Fundamental Neuroscience. New York, NY, USA: Churchill Livingstone; 1997. pp. 129–41. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Millan MJ. The induction of pain: an integrative review. Progress in Neurobiology. 1999;57(1):1–164. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(98)00048-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Millan MJ. Descending control of pain. Progress in Neurobiology. 2002;66(6):355–474. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(02)00009-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rauch SL, Shin LM, Wright CI. Neuroimaging studies of amygdala function in anxiety disorders. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2003;985:389–410. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb07096.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fiot J, Baghdikian B, Boyer L, et al. HPLC quantification of uncarine D and the anti-plasmodial activity of alkaloids from leaves of Mitragyna inermis (Willd.) O. Kuntze. Phytochemical Analysis. 2005;16(1):30–33. doi: 10.1002/pca.806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Suchomelová J, Bochořáková H, Paulová H, Musil P, Táborská E. HPLC quantification of seven quaternary benzo[c]phenanthridine alkaloids in six species of the family Papaveraceae. Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis. 2007;44(1):283–287. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jouany J, Poitevin B, Saint-Jean Y, Masson JL Boiron. Pharmacologie et Matière Médicale Homéopathique. Paris, France: CEDH; 2003. Gelsemium sempervirens; pp. 337–83. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bitran D, Shiekh M, McLeod M. Anxiolytic effect of progesterone is mediated by the neurosteroid allopregnanolone at brain GABA(A) receptors. Journal of Neuroendocrinology. 1995;7(3):171–177. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.1995.tb00744.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Agís-Balboa RC, Pinna G, Zhubi A, et al. Characterization of brain neurons that express enzymes mediating neurosteroid biosynthesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006;103(39):14602–14607. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606544103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Krieger NR, Scott RG. Nonneuronal localization for steroid converting enzyme: 3α-hydroxysteroid oxidoreductase in olfactory tubercle of rat brain. Journal of Neurochemistry. 1989;52:1866–1870. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1989.tb07269.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Patte-Mensah C, Penning TM, Mensah-Nyagan AG. Anatomical and cellular localization of neuroactive 5 alpha/3 alpha-reduced steroid-synthesizing enzymes in the spinal cord. The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 2004;477:286–299. doi: 10.1002/cne.20251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dudeck O, Lübben S, Eipper S, et al. Evidence for strychnine-sensitive glycine receptors in human amygdala. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Archives of Pharmacology. 2003;368(3):181–187. doi: 10.1007/s00210-003-0786-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kirsch J. Glycinergic transmission. Cell and Tissue Research. 2006;326(2):535–540. doi: 10.1007/s00441-006-0261-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Legendre P. The glycinergic inhibitory synapse. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 2001;58(5-6):760–793. doi: 10.1007/PL00000899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lynch JW. Molecular structure and function of the glycine receptor chloride channel. Physiological Reviews. 2004;84(4):1051–1095. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00042.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kitajima M, Urano A, Kogure N, Takayama H, Aimi N. New oxindole alkaloids and iridoid from Carolina jasmine (Gelsemium sempervirens Ait. f.) Chemical & Pharmaceutical Bulletin. 2003;51:1211–1214. doi: 10.1248/cpb.51.1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Schun Y, Cordell GA. 14β-hydroxygelsedine, a new oxindole alkaloid from Gelsemium sempervirens. Journal of Natural Products. 1985;48(5):788–791. doi: 10.1021/np50041a012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Schun Y, Cordell GA. Cytotoxic steroids of Gelsemium sempervirens. Journal of Natural Products. 1987;50(2):195–198. doi: 10.1021/np50050a012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]