Abstract

Peroxisome biogenesis disorders (PBDs) are multisystemic autosomal recessive disorders resulting from mutations in PEX genes required for normal peroxisome assembly and metabolic activities. Here, we evaluated the potential effectiveness of aminoglycoside G418 (geneticin) and PTC124 (ataluren) nonsense suppression therapies for the treatment of PBD patients with disease-causing nonsense mutations. PBD patient skin fibroblasts producing stable PEX2 or PEX12 nonsense transcripts and Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells with a Pex2 nonsense allele all showed dramatic improvements in peroxisomal very long chain fatty acid catabolism and plasmalogen biosynthesis in response to G418 treatments. Cell imaging assays provided complementary confirmatory evidence of improved peroxisome assembly in G418-treated patient fibroblasts. In contrast, we observed no appreciable rescue of peroxisome lipid metabolism or assembly for any patient fibroblast or CHO cell culture treated with various doses of PTC124. Additionally, PTC124 did not show measurable nonsense suppression in immunoblot assays that directly evaluated the read-through of PEX7 nonsense alleles found in PBD patients with rhizomelic chondrodysplasia punctata type 1 (RCDP1). Overall, our results support the continued development of safe and effective nonsense suppressor therapies that could benefit a significant subset of individuals with PBDs. Furthermore, we suggest that the described cell culture assay systems could be useful for evaluating and screening for novel nonsense suppressor therapies.

Keywords: peroxisome biogenesis disorder, ataluren, geneticin, nonsense mutation

Aminoglycoside antibiotics, such as gentamicin and its analog G418 (geneticin), can promote the translational read-through of stop codons (i.e. nonsense suppression) in cultured human cells and genetically engineered mouse models, as reviewed in [Hainrichson et al., 2008; Zingman et al., 2007]. This has lead to small-scale clinical studies to evaluate gentamicin treatments in patients with nonsense mutations that result in cystic fibrosis [Clancy et al., 2001; Linde et al., 2007; Sermet-Gaudelus et al., 2007; Wilschanski et al., 2000; Wilschanski et al., 2003], Duchenne and Becker muscular dystrophy [Malik et al., 2010; Politano et al., 2003; Wagner et al., 2001], hemophilia A and B [James et al., 2005], factor VII deficiency [Pinotti et al., 2006], Hailey-Hailey disease [Kellermayer et al., 2006] and McArdle disease [Schroers et al., 2006]. To date, no lasting clinical benefits have been reported for individuals receiving gentamicin nonsense suppression therapies. Furthermore, their long-term toxicity and route of administration impede their clinical applications for chronic genetic disorders [Guthrie, 2008; Martinez-Salgado et al., 2007].

PTC124 (ataluren) is an orally delivered non-aminoglycoside compound reported to promote the translational read-through of premature stop codons [Welch et al., 2007]. As a result of its observed activity in primary human cells and mouse models, PTC124 is currently in clinical trials for the treatment of cystic fibrosis and Duchene's muscular dystrophy caused by nonsense mutations [Hirawat et al., 2007; Kerem et al., 2008]. PTC124 has demonstrated favorably low toxicity in these trials [Hirawat et al., 2007; Kerem et al., 2008]. Similar to observations made for gentamicin [Clancy et al., 2001; Sermet-Gaudelus et al., 2007; Wilschanski et al., 2003], CF patients receiving PTC124 have shown reduced electrophysiological abnormalities and increased apical CFTR protein expression in their nasal epithelial tissue [Kerem et al., 2008; Sermet-Gaudelus et al., 2010]. However, the clinical efficacy of PTC-124 for the treatment of CF or DMD has not yet been reported in the scientific literature.

Peroxisomal biogenesis disorders (PBDs) are a group of autosomal recessive multisystemic disorders that are promising targets for nonsense suppressor therapies [Steinberg et al., 2006; Wanders, 2004; Weller et al., 2003]. Approximately 80% of PBD cases fall within the Zellweger spectrum (PBD-ZSD) category with the remaining cases classified as rhizomelic chondrodysplasia punctata type 1 (RCDP1) [Steinberg et al., 2004]. Over 90% of PBD-ZSD patients have mutations in a group of five PEX genes (PEX1, PEX6, PEX10, PEX12, and PEX26) crucial for normal peroxisome assembly and function [Steinberg et al., 2004]. Based on data from recent studies [Steinberg et al., 2004; Yik et al., 2009], nonsense mutations account for ∼15% of the disease-causing PEX alleles found in PBD-ZSD patients. RCDP1 is an especially attractive candidate for nonsense suppressor therapies since the common PEX7 L292X nonsense mutation, accounting for over 60% of mutant alleles [Braverman et al., 2002; Braverman et al., 2000; Motley et al., 2002], yields a stable transcript [Braverman et al., 2002]. Since PBD patients with residual mutant PEX gene function tend to have milder medical conditions [Moser, 1999; Steinberg et al., 2006], a modest rescue of PEX gene activity could provide considerable clinical benefits for patients with more severe forms of disease.

Here, we used complementary experimental approaches to explore the potential effectiveness of nonsense suppressor therapies for PBDs. We evaluated peroxisome lipid metabolism and assembly in a collection of PBD patient skin fibroblasts with PEX gene nonsense mutations before and after G418 and PTC124 treatments. These functional assays focus on the downstream biochemical and cellular consequences of PEX gene mutations. In parallel, we used immunoblot assays to evaluate directly the activity of PTC124 in promoting the translational read-through of PEX7 nonsense mutations found in RCDP1 patients. Collectively, our studies provide evidence that the development of safe and effective nonsense suppressor therapies could benefit significant numbers of PBD patients.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture and Drug Testing

Primary fibroblast cultures from patients and healthy controls were obtained from the Peroxisomal Disease Laboratory at the Kennedy Krieger Institute and Coriell Institute Cell Repository, respectively. Prior to testing, cells were grown to confluence for 48 hours at 37 °C with 5% CO2, as described [Karaman et al., 2003]. G418 was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich and PTC124 from Enzo Life Sciences and Dr. Christopher Austin at the National Institutes of Health. The 10 mg/ml G418 and 10 mM PTC124 stock solutions were freshly made in 1× PBS and DMSO, respectively.

Quantitative Real-Time PCR

Fibroblasts from patients and healthy controls were grown to confluence for 48 hours and total RNA was extracted by the RNA STAT-60™ (Tel-Test) method. cDNA was prepared with the iScript™cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bio-Rad) and PCR reactions were performed in triplicate with SYBR Green PCR master mix and reverse transcriptase (Applied Biosystems) with PEX gene specific primers. RT-PCR reactions were run on a DNA Engine Opticon 2 system (MJ Research).

Immunofluorescence

Fibroblasts and CHO cells were plated on 6-well plates for 24 hour at 37 °C and treated in duplicate with either 10 or 50 μg/ml of G418 or PBS media for three or ten days. Fibroblasts were also seeded as above and treated in duplicate with 50 μM PTC124 or DMSO media for three or ten days. Cells were processed and data collected as previously reported [Yik et al., 2009].

Fatty Acid and Plasmalogen Analyses

Drug-containing media was replenished every three days until cells were assayed at the designated three or ten day time point. Cell extracts were processed and total fatty acids analyzed using capillary GC with flame ionization detection, as described [Moser and Moser, 1991]. C16:0 DMA and C18:0 DMA levels also were measured by capillary GC with flame ionization detection, as described [Bjorkhem et al., 1986; Steinberg et al., 2008].

Immunoblotting

PEX7 mutant cDNAs were constructed by site-directed mutagenesis using wild type PEX7 as template and inserted N-terminal to and in-frame with Gal4 BD present in the pBIND plasmid (Promega) to create different pBIND-PEX7 constructs. Cultured HEK293 cells were transfected in triplicate using 0.25 μg of jetPEI (Polyplus-Transfection Inc.) with the designated pBIND-PEX7 construct. Twenty-four hours post-transfection, cells were treated with PTC124 (10, 50 μM). Whole cell lysates were obtained for immunoblotting using anti-Gal4 antiserum (Millipore) to detect the designated BIND-PEX7 protein. Experiments were performed in triplicate and repeated four times.

Results

We chose cultured skin fibroblasts from four healthy controls, seven PBD-ZSD patients with two previously confirmed mutant alleles in the PEX2, PEX10, PEX12, or PEX26 genes, and one RCDP1 patient that was homozygous for the common PEX7 L292X mutation [Moser, 1999; Steinberg et al., 2006] (Table I, cultures A-H). This includes cultures from six PBD-ZSD patients with at least one PEX gene nonsense mutation and a patient with two PEX2 frame-shift mutations (culture D), which served as a negative control. In addition, we selected the Pex2 (R123X) null Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) ZR-82 cell line (Table I), previously reported to show improved peroxisomal lipid metabolic functions in response to G418 treatment and the wild type CHO K1 parental line [Allen and Raetz, 1992].

TABLE I. PBD-ZSD and RCDP1 Patient Skin Fibroblast and Mutant CHO Cell Cultures Evaluated.

| Culture | Mutant genea | Genotype Allele 1 | Genotype Allele 2 | Levelc | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coding | Contextb | Protein | Coding | Contextb | Protein | |||

| Ad | PEX2 | 355C>T | GAA CGA TGA | R119X | 355C>T | GAA CGA TGA | R119X | 87% |

| Bd | PEX2 | 355C>T | GAA CGA TGA | R119X | 355C>T | GAA CGA TGA | R119X | 77% |

| C | PEX2 | 373C>T | UUU CGA AAC | R125X | 373C>T | UUU CGA AAC | R125X | 103% |

| D | PEX2 | 273delT | -- | P91fs | 273delT | -- | P91fs | 54% |

| E | PEX7 | 875T>A | GGU UUA GAC | L292X | 875T>A | GGU UUA GAC | L292X | 50% |

| F | PEX10 | 4delG | -- | A2fs | 892G>T | CTG GAG GAG | E298X | 23% |

| G | PEX12 | 538C>T | CUU CGA UAC | R180X | 887_888delTC | -- | L296fs | 48% |

| H | PEX26 | 296G>A | CGG UGG CAA | W99X | 296G>A | CGG UGG CAA | W99X | 25% |

| ZR-82e | Pex2 | 367C>T | TTT CGA AAC | R123X | presumed deleted null allele | NT | ||

RefSeq IDs: PEX2 (NM_000318.2), PEX10 (NM_153818.1), PEX12 (NM_000286.2), and PEX26 (NM_017929.4).

Codons (5′ - 3′) affected by nonsense mutations (mutated base underlined) and flanking codons are provided. “--” = frameshift mutation.

Average percent abundance of mutated PEX transcripts relative to the cognate PEX transcripts in four healthy controls. All quantitative PCR experiments were performed in triplicate. NT = not tested.

Derived from different PBD-ZSD patients with the same PEX2 mutations.

Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells.

Pex Gene Expression in Cultured Fibroblasts

Based on global gene expression profiling data, cultured fibroblasts from healthy donors show abundant PEX2 transcript levels (∼90th percentile of all transcripts surveyed), but more modest levels of the PEX7, PEX10, PEX12, or PEX26 transcripts (30-70th percentile) (Supplemental Table I). Using quantitative PCR assays, we found that fibroblasts that were homozygous for PEX2 or PEX7 nonsense mutations (cultures A, B, C, and E), homozygous for PEX2 frame-shift mutations (culture D), or compound heterozygous for PEX12 nonsense and frame-shift alleles (culture G) produced substantial levels of mutant PEX gene transcripts (i.e. at least 40% of those in healthy controls) (Table I). This finding is consistent with the prediction that these mutant transcripts would not undergo nonsense-mediated decay (NMD) due to their sequence context [Bhuvanagiri et al., 2010]. We prioritized cultures A, B, C, and E for drug testing since their homozygous, stable nonsense PEX transcripts should provide the greatest opportunity for producing biologically significant levels of the corresponding full-length PEX protein. We also prioritized culture G since it is highly likely that the PEX12 nonsense allele is producing stable mutant transcript. Finally, we note that culture D serves as a rigorous negative control since its frame-shift alleles produce stable transcript.

Cell Viability in Response to Drug-Treatments

We used MTT assays [Mosmann, 1983] to evaluate the viability of cultured fibroblasts from patients (A-H) and three healthy controls after drug treatments (Supplemental Fig. 1). All cultures treated with low dose G418 (5 and 10 μg/ml) showed over 70% viability at three days and over 40% viability at ten days. Cultures treated with high dose G418 (50 μg/ml) showed non-uniform viability at three days and consistently low viability at 10 days (15% average viability). All cultures exposed to low dose PTC124 (50 μM) showed over 80% viability at three and ten days. In exploratory studies, the 100 μM PTC124 dose lowered cell viability at three and ten days (58 and 35% average viability, respectively). High dose PTC124 (250 μM) was toxic to all cultures tested at both times (less than 10% viability at ten days). Finally, CHO ZR-82 and K1 cells treated with 5, 10, or 50 μg/ml G418 or 50 μM PTC124 showed over 70% viability at three and ten days. Collectively, the results from these MTT assays were used to inform the doses chosen for this study and aid in the interpretation of responses to drug treatments.

Rescue of VLCFA Catabolism

Consistent with the known defects in peroxisomal β-oxidation of very long chain fatty acids (VLCFA) [Steinberg et al., 2006], cultured fibroblasts from PBD-ZSD patients and CHO ZR-82 cells had over 3-fold elevated C26:0/C22:0 fatty acid ratios relative to healthy controls. As expected, culture E from a RCDP1 patient had C26:0/C22:0 fatty acid ratios similar to those of healthy controls. This reflects the fact that RCDP1 patients have normal VLCFA β-oxidation. In singleton exploratory experiments evaluating cultures A-H and CHO ZR-82 cells treated with 50 μg/ml G418 for three days, PBD-ZSD cultures A and C with PEX2 nonsense mutations and PBD-ZSD culture G with PEX12 nonsense mutations showed ≥25% decreases in their C26:0/C22:0 ratios (Supplemental Table II). In similar exploratory studies, none of the PBD cell cultures (A-H) or CHO-ZR-82 cells treated with 50 μM PTC124 for three days showed this type of response (Supplemental Table II).

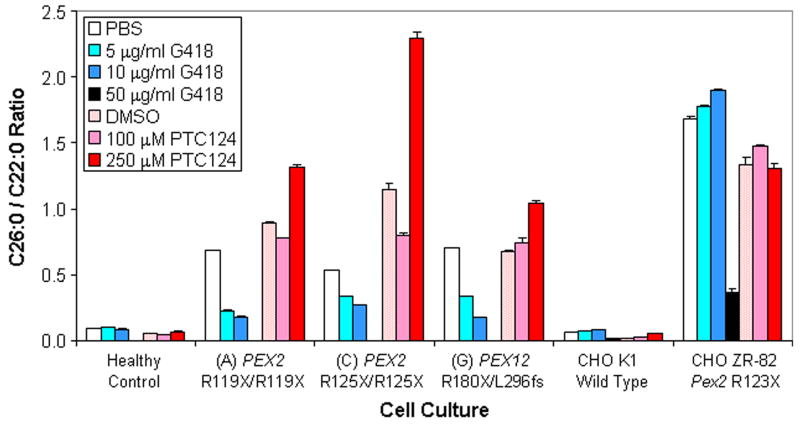

To follow-up on cultures showing the most promising rescue of VLCFA catabolism, we tested in triplicate the effects of three and ten day G418 and PTC124 treatments on the PEX2 (culture A), PEX2 (culture C), and PEX12 (culture G) mutant fibroblasts (Table II). We also included CHO ZR-82 cells due to literature precedent [Allen and Raetz, 1992]. Prior to drug-treatment, all patient cultures showed over 6-fold elevated C26:0/C22:0 ratios relative to the healthy control. Following ten day G418 treatment (5 and 10 μg/ml), all patient cultures demonstrated substantial decreases in their C26:0/C22:0 ratios (Fig. 1). Cultures A and G now had (i) less than 3.5-fold elevated C26:0/C22:0 ratios relative to the drug-treated healthy control and (ii) at least 53% decreases in their C26:0/C22:0 ratio compared to PBS vehicle control (P < 0.001). However, culture D with two PEX2 frame-shift mutations and healthy control cultures showed no significant response to ten day G418 treatments (5 and 10 μg/ml) (Table II). Untreated CHO ZR-82 cells had a 25.5-fold elevated C26:0/C22:0 ratio relative to CHO K1 wild type cells. After ten day treatments with 50 μg/ml G418, CHO ZR-82 cells had (i) only a 17.8-fold elevated C26:0/C22:0 ratio relative to drug-treated CHO K1 cells and (ii) a 78% decrease in C26:0/C22:0 ratio compared to PBS vehicle control (P < 0.001). In contrast, PTC124 treatments (100 and 250 μM) did not result in significantly decreased C26:0/C22:0 ratios (over 50% reduction, P < 0.01) for any human or CHO cell tested at three and ten days.

TABLE II. Summary of Biochemical Rescue in PBD Patient Fibroblast Cultures.

| Culture | Treatment | Evidence of biochemical rescuea | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C16:0 DMA | C16:0 DMA | C18:0 DMA | C18:0 DMA | VLCFA | VLCFA | ||

| 3 daysb | 10 daysb | 3 daysb | 10 daysb | 3 daysc | 10 daysc | ||

| A | 5 μg/ml G418 | - - | +++ | - - | +++ | - - | +++ |

| A | 10 μg/ml G418 | - | +++ | + | +++ | - | +++ |

| A | 100 μM PTC124 | - - | - | - - | - - | - - | - |

| A | 250 μM PTC124 | - - | + | - | - - | - | - |

| C | 5 μg/ml G418 | - - | +++ | - - | +++ | - - | ++ |

| C | 10 μg/ml G418 | - - | +++ | - - | +++ | - | ++ |

| C | 100 μM PTC124 | - - | - | - - | - | - | - |

| C | 250 μM PTC124 | - - | - - | - - | - - | - | - |

| D | 5 μg/ml G418 | - - | - - | - - | - - | - - | - |

| D | 10 μg/ml G418 | - - | - - | - - | - - | - - | - |

| E | 5 μg/ml G418 | - - | - - | - - | - - | NA | NA |

| E | 10 μg/ml G418 | - - | - | - - | - | NA | NA |

| E | 100 μM PTC124 | - - | - - | - - | - - | NA | NA |

| G | 5 μg/ml G418 | - - | + | - - | ++ | - - | ++ |

| G | 10 μg/ml G418 | - - | + | - | ++ | - - | +++ |

| G | 100 μM PTC124 | - - | - - | - - | - | - - | - - |

| G | 250 μM PTC124 | - - | - - | - - | - - | - - | - |

All samples were treated with drug or vehicle controls for three and ten days in triplicate.

Designated DMA levels are >75% (+++), 50-75% (++), 25-50% (+), or <25% (-) of drug-treated healthy control with P < 0.01. ‘- -’ indicates P > 0.01. P-values are calculated based on a two-tailed Student's t-test.

C26:0/C22:0 ratio is 2-3 fold (+++), 3-4 fold (++), 4-5 fold (+), or >5 fold (-) elevated relative to drug-treated healthy control with P < 0.01. ‘- -’ indicates P > 0.01. ‘NA’ indicates not applicable as PEX7 mutants are expected to show similar VLCFA ratios relative to healthy controls.

Fig. 1.

Rescue of VLCFA metabolic activity in PBD patient fibroblasts and CHO ZR-82 cells. We report the average C26:0/C22:0 fatty acid ratios (Y-axis) for healthy control fibroblast cultures, PEX mutant fibroblast cultures, CHO K1 wild type cells, and CHO ZR-82 Pex2 mutant cells treated with G418, PTC124, or appropriate vehicle control (0.1% PBS or 2.5% DMSO) for ten days. The culture designation (Table I) and genotype of the treated cells are provided on the X-axis. All experiments were conducted in triplicate and error bars represent the standard error of the mean (SEM).

Rescue of Plasmalogen Biosynthesis

Plasmalogens are ether glycerophospholipids whose synthesis is dependent upon peroxisome activity [Braverman et al., 2010; Gorgas et al., 2006; van den Bosch et al., 1992]. We evaluated plasmalogen abundance in cultured cells by measuring amounts of C16:0 and C18:0 fatty alcohols attached to the sn-1 position of the glycerol backbone. These are detected as dimethyl acetal (DMA) derivatives after acid methanolysis of the vinyl-ether bond. In agreement with prior reports [Steinberg et al., 2006], PBD-ZSD and RCDP1 fibroblasts had over 45% reductions in C16:0 DMA and C18:0 DMA levels relative to healthy controls. In singleton exploratory experiments, control fibroblasts or wild type CHO cells showed less than 20% increases in their C16:0 DMA and C18:0 DMA levels after three day treatments with 50 μg/ml G418 or 50 μM PTC124 (Supplemental Table II). However, patient cells with PEX2 (cultures A, B, and C) and PEX12 (culture G) nonsense mutations showed over 30% increases in C16:0 DMA and over 90% increases in C18:0 DMA levels after three day G418 treatments. While cultures A and B share the same PEX2 nonsense mutations and both provide evidence of G418-mediated rescue of plasmalogen biosynthesis, we focused our follow-up analyses on culture A since it (unlike culture B) also showed a robust reduction in its C26:0/C22:0 ratio (Supplemental Table II). After three day treatments with 50 μg/ml G418, CHO ZR-82 cells demonstrated an over 50% increase in C18:0 DMA levels, but no increase in C16:0 DMA levels (Supplemental Table II). Only PBD-ZSD culture A and RCDP1 culture E provided promising preliminary results in response to PTC-124 treatments (47 and 28% increases in C16:0 DMA levels, and 53 and 24% increases in C18:0 DMA levels, respectively). However, culture A showed no evidence of increased VLCFA catabolism, as discussed above.

To rigorously evaluate plasmalogen biosynthesis rescue over extended periods of time, we measured in triplicate C16:0 DMA and C18:0 DMA levels in PBD-ZSD PEX2 (cultures A and C) and PEX12 (culture G) mutant cell cultures treated with 5 and 10 μg/ml G418 or 100 and 250 μM PTC124 for ten days (Fig. 2 and S2). All three G418-treated patient cells (A, C, and G) showed a robust rescue of C16:0 DMA and C18:0 DMA levels (35-147% of drug-treated healthy controls). Additionally, all these cultures demonstrated significant increases in both C16:0 DMA and C18:0 DMA levels compared to PBS vehicle controls (2.5 to 6.8-fold and 3.8 to 8.2-fold respectively, P < 0.01). In contrast, none of these cultures showed significant increases in C16:0 DMA and C18:0 DMA levels in response to PTC124.

Fig. 2.

Rescue of plasmalogen biosynthesis in PBD patient fibroblasts and CHO Pex2 nonsense mutant cells. We report plasmalogen levels in healthy control fibroblast cultures, PEX mutant fibroblast cultures, CHO K1 wild type cells, and CHO ZR-82 Pex2 mutant cells treated with G418, PTC124, or appropriate vehicle control (0.1% PBS or 2.5% DMSO) for ten days. For each culture, we provide the average (A) C16:0 DMA and (B) C18:0 DMA levels (Y-axis). The culture designation (Table I) and genotype of the treated cells are provided on the X-axis. All experiments were conducted in triplicate and error bars represent the SEM.

In parallel, we treated PEX7-mutant RCDP1 patient fibroblasts (culture E) with 5 and 10 μg/ml G418 or 100 μM PTC124 for ten days (Supplemental Fig. 2). The RCDP1 patient fibroblasts treated with 10 μg/ml G418 showed a modest increase (1.5-fold, P < 0.01) in C18:0 DMA levels relative to PBS vehicle controls. However, the C16:0 DMA and C18:0 DMA levels of these drug-treated RCDP1 patient fibroblasts were only 15-18% of the corresponding drug-treated healthy control fibroblasts. As above, these cells showed no significant increases in C16:0 DMA and C18:0 DMA levels in response to PTC124.

Consistent with prior reports [Allen and Raetz, 1992], CHO ZR-82 mutant cells treated with 50 μg/ml G418 for ten days showed dramatic rescue of C16:0 DMA and C18:0 DMA levels relative to drug-treated wild type CHO K1 cells (82% and 57% respectively) and significant improvement in C16:0 DMA and C18:0 DMA levels compared to PBS vehicle controls (5.6 and 3.3-fold increases respectively, P < 0.001) (Fig. 2). However, PTC124-treated CHO ZR-82 mutant cells showed no notable differences in C16:0 DMA or C18:0 DMA levels.

Rescue of Peroxisome Assembly

We used immunofluorescence (IF) assays to evaluate peroxisome assembly in cultured cells. For PBD-ZSD patient cultures, which have defects in both the peroxisome targeting signal 1 (PTS1) and peroxisome targeting signal 2 (PTS2) pathways [Steinberg et al., 2006], we used PMP70 and catalase as markers for peroxisome membrane and matrix proteins, respectively. For RCDP1 cultures, which only have defects in the PTS2 import pathway [Steinberg et al., 2006], we used PEX13 and thiolase as markers for peroxisome membrane and matrix proteins, respectively. In agreement with prior reports [Steinberg et al., 2006], PBD-ZSD and RCDP1 patient cells showed diffuse cytoplasmic localization of PTS1 and PTS2 matrix protein markers, respectively. For PBD-ZSD cells there were reduced numbers of normal peroxisomes, and an increased number of peroxisomal vesicles with no discernable evidence of matrix protein import. Three day G418 (50 μg/ml) treatments of cultures A, C, E, F, and H did not result in a detectable improvement in peroxisome assembly (Supplemental Fig. 3). However, we found modest evidence of improved assembly for culture G in some experiments (Supplemental Fig. 4U), but not others (Supplemental Fig. 3J). PTC124 (50 μM) treatments did not result in an appreciable change in peroxisome assembly in any PBD-ZSD or RCDP1 fibroblast cultures tested (A, C, E, F, G, and H) (Supplemental Fig. 5, Supplemental Fig. 6, and Supplemental Fig. 8).

Given the positive results in the biochemical rescue of the PEX2 (cultures A and C), and PEX12 (culture G) mutant fibroblast cultures, we evaluated peroxisome assembly in cells treated with 10 and 50 μg/ml G418 or 50 μM PTC124 for three and ten days. We observed improved peroxisome assembly in the G418-treated PEX2 mutant cultures A and C at ten days (Fig. 3C, 3E, and Supplemental Figs. 4K, 4L, 4Q, 4R) and PEX12 (culture G) mutant fibroblasts at both three and ten days (Fig. 3G and Supplemental Fig. 4U, 4W, 4X). PBD-ZSD cultures C and G were almost indistinguishable from control cultures after ten day 50 μg/ml G418 treatment (Fig. 3C, 3G). Marginal improvements were observed for culture A in response to ten day G418 treatments. In contrast, cultures A, C, and G treated with PTC124 showed no discernable improvements in peroxisome assembly (Supplemental Fig. 6).

Fig. 3.

Peroxisome assembly in G418-treated PBD patient fibroblasts. We conducted immunofluorescence-based peroxisome assembly assays on patient fibroblasts treated with indicated vehicle control or G418 for ten days. Anti-human PMP70 (green) and catalase (red) antibodies were used to highlight the peroxisome membrane and matrix proteins, respectively. Results from (A) healthy control fibroblasts treated with PBS vehicle control, (B) PEX2 p.R125X/p.R125X culture C treated with PBS vehicle control, (C) culture C treated with 50 μg/ml G418, (D) PEX2 p.R119X/p.R119X culture A treated with PBS vehicle control, (E) culture A treated with 50 μg/ml G418, (F) PEX12 p.R180X/p.L296fs culture G treated with PBS vehicle control, (G) culture G treated with 50 μg/ml G418 are provided. Punctate yellow staining indicates co-localization of peroxisome membrane and matrix markers. Enlarged views of the white boxed areas in the left panels are provided in the adjacent right panels. The vehicle control is 0.5% PBS.

Additionally, neither G418 nor PTC124 treatment rescued peroxisome assembly in RCDP1 patient fibroblasts at three or ten days (Supplemental Fig. 7, Supplemental Fig. 8). Finally, in agreement with prior studies [Allen and Raetz, 1992], we observed no rescue of peroxisome assembly in G418-treated Pex2-R123X CHO cells, despite the observed biochemical rescue (Supplemental Fig. 9).

PEX7 Reporter Gene Model System

Given that over 60% of RCDP1 patients could benefit from non-toxic nonsense suppressor therapies [Braverman et al., 2002; Braverman et al., 2000; Motley et al., 2002], we developed reporter gene assays to reevaluate if PTC124 could efficiently promote the translational read-through of three naturally occurring PEX7 nonsense alleles, including the common L292X mutation (Fig. 4). HEK293 cells were transfected with a pBIND-PEX7 plasmid that expresses a Gal4-PEX7 fusion protein containing a PEX7 nonsense mutation and then cultured in PTC124 (10 or 50 μM) for 72 hours. Afterwards, immunoblotting was performed on whole cell lysates with anti-Gal4 antibody. Although all truncated forms of the PEX7-mutant proteins were present, there was no evidence of full length Gal4-PEX7 fusion protein production in the drug-treated cells.

Fig. 4.

Read-through of PEX7 nonsense alleles in PTC124-treated cells. HEK293 cells were transfected with PEX7-pBIND constructs that express Gal4-PEX7 fusion proteins of the indicated PEX7 p.R152X, p.W206X, p.R232X, and p.L292X genotypes (see Methods for details). After 24 hours, the transfected cell populations were cultured in 0, 10 or 50 μM PTC124 for 72 hours. Whole cell protein lysates (25 μg per lane) were separated on agarose gels, transferred to a nylon membrane, and incubated with Gal4 antibody which detects all PEX7-pBIND fusion proteins. The PEX7 genotype and drug concentration are provided on top of each lane. M = mock transfection. The final lane depicts results from cells transfected with a plasmid expressing full length PEX7-pBIND (highlighted in blue box). Truncated mutant PEX7-pBIND proteins are highlighted by red boxes.

Discussion

We demonstrated that cultured PBD-ZSD patient skin fibroblasts with stable PEX2 or PEX12 nonsense transcripts showed dramatic improvements in peroxisomal lipid catabolic and anabolic activities in response to the chosen G418 treatments, but not the PTC124 treatments investigated (Table II and Figs. 1-2). In all cases, G418-mediated rescue was observed by ten days using treatment conditions that result in moderate reductions in cell viability (Supplemental Fig. 1). In follow-up cell imaging assays, we observed that the rescue of peroxisomal lipid metabolic functions was coupled with improved peroxisome assembly. This ranged from robust (culture G) to marginal (culture A) increases in vesicles that stain positive for peroxisome membrane (PMP70) and matrix (catalase) markers (Fig. 3 and Supplemental Fig. 4). These quantitative biochemical assays and qualitative peroxisome assembly assays provided complementary means of surveying peroxisome function and structure in drug-treated patient cells.

Given the unavailability of quality PEX2 and PEX12 antibodies for immunoblot or IF-assays, we cannot formally state the mechanistic basis for the G418-mediated rescue of peroxisome lipid metabolic activities or assembly in patient cells. However, the nonsense suppressor activity of G418 has been demonstrated in multiple contexts, as reviewed in [Hainrichson et al., 2008; Zingman et al., 2007]. In addition, the decreased C26:0/C22:0 fatty acid ratio, increased C16:0 and C18:0 DMA levels, and improved peroxisome assembly in cultures A, C, and G provide compelling positive evidence of increased mutant PEX gene function. Furthermore, the non-responsiveness of culture D with two PEX2 frame-shift mutations (culture D) to G418 treatments strongly suggests that the biochemical rescue observed in fibroblast cultures A and C with PEX2 nonsense mutations is related to their genotypes. Likewise, healthy control fibroblasts show no substantive changes in peroxisomal lipid metabolism in response to G418, relative to PBS vehicle controls.

We included Pex2-mutant CHO ZR-82 cells in our surveys due to a prior report that G418 treatment could rescue their peroxisomal lipid metabolic functions [Allen and Raetz, 1992]. In this initial publication, the genotype of these CHO ZR-82 cells and the potential mode of G418 activity were not discussed. Subsequently, the same group demonstrated that the CHO ZR-82 cells contained a Pex2 p.R123X nonsense mutation and that non-responsive Pex2-mutant CHO cells in the original study had a Pex2 frame-shift mutation [Thieringer and Raetz, 1993]. Thus, we theorized that the G418-mediated biochemical rescue in CHO ZR-82 cells resulted from the nonsense suppressor activity of G418. In agreement with the prior study [Allen and Raetz, 1992], our G418-treated CHO ZR-82 cells showed a substantial rescue of VLCFA metabolism and plasmalogen biosynthesis. In contrast, the CHO ZR-82 cells were non-responsive to PTC124 treatments. In follow-up cell imaging assays, we found no discernable rescue of peroxisome assembly in G418-treated CHO ZR-82 cells, also in agreement with prior studies [Allen and Raetz, 1992]. This indicates that biochemical assays can be more sensitive than standard assembly assays for detecting low level peroxisome functions.

In our synthetic model system, we could not detect PTC124 mediated read-through of PEX7 nonsense mutations by immunoblotting. This strongly suggests that the lack of improved plasmalogen biosynthesis or peroxisome assembly in RCDP1 fibroblasts (culture E, homozygous for the common PEX7 p.L292X mutation) in response to PTC124 treatments is not due to the production of non-functional full-length PEX7 protein. Nevertheless, our immunoblotting assays may lack the sensitivity to detect small increases in full length PEX7 protein in response to PTC124 treatments.

The general non-responsiveness of PBD patient skin fibroblast and CHO ZR-82 cultures to PTC124 treatments could add to on-going discussions concerning its mode of biological activity [Auld et al., 2009; Inglese et al., 2009; Peltz et al., 2009]. PTC124 was initially discovered based on its ability to promote firefly luciferase (FLuc) reporter gene activity in mammalian cell culture assays [Welch et al., 2007]. Although this increase was reportedly caused by the translational read-through of an engineered stop codon, PTC124 can directly increase the activity of the FLuc protein product under specific assay conditions [Auld et al., 2009]. Subsequently, it has been demonstrated that under certain circumstances, PTC124 can be converted to the acyl-AMP mixed anhydride adduct, PTC124-AMP, which can bind to and stabilize the FLuc protein and prevent other inhibitors from binding [Auld et al., 2010; Thorne et al., 2010]. This can result in increased FLuc activity in the absence of translational read-through. Nevertheless, PTC124 has been reported to promote the translational read-through in FLuc activity assays under different assay conditions [Peltz et al., 2009]. Furthermore, PTC124 has been reported to promote the read-through of premature stop codons in multiple other biological assay systems including DMD [Welch et al., 2007] and CF [Du et al., 2008] mouse models and myotubes from a patient with Miyoshi myopathy [Wang et al., 2010]. Most intriguingly, PTC124 treatments can result in substantially increased CFTR activity in a subset of CF patients with disease-causing nonsense mutations [Kerem et al., 2008; Sermet-Gaudelus et al., 2010].

The lack of evidence for PTC124 nonsense suppressor activity in our assays could be due to numerous factors, including the sequence context of the premature stop codons and treatment regimen. In one reporter gene model system (subject to interpretation as discussed above), PTC124 showed maximal activity to promote the read-through of a UGA stop codon with lesser activities for UAG and UAA stop codons [Welch et al., 2007]. Here, PBD-ZSD cultures A, B, C, G, and CHO ZR-82 cells had premature UGA stop codons (Table I), but did not show consistent increases in peroxisome metabolic functions in response to PTC124 treatments. In terms of PTC124 concentration, we chose the low exploratory (50 μM) dose based on studies of primary human muscle cells [Welch et al., 2007] and the intermediate (100 μM) and high (250 μM) doses based on observed cell toxicity (Supplemental Fig. 1). Furthermore, we demonstrated that the ten day time point was sufficient for the G418-mediated rescue of peroxisome metabolic functions and/or assembly in the discussed PBD-ZSD patient fibroblast cultures and CHO ZR-82 cells. While we cannot exclude the possibility that PTC124 has substantial nonsense suppressor activity in PBD patient cells under different treatment regimens, our results suggest that any theoretical window of robust PTC124 nonsense suppressor activity in our cell culture models would be narrow or especially sensitive to assay conditions.

Based on the observed activity of G418 in our functional assays, we provide evidence that nonsense suppressor therapies could be beneficial to a subset of patients with PBDs. The development of safe and effective nonsense suppressor therapies for PBDs will continue to be challenging as numerous technical concerns needed to be addressed, including the ability to cross the blood-brain barrier. Regardless of the pharmacological properties of different nonsense suppressor therapies, it is likely that only patients with nonsense alleles yielding stable mutant transcripts could benefit from these interventions. Likewise, the identity of the amino acid incorporated at the premature stop codon would need to be compatible with protein function in order for any nonsense suppressor therapy to be effective. To help address these challenges, we have identified human and CHO cell culture model systems and functional assays that can be used to validate the effectiveness of candidate nonsense suppressor drugs. Other well-characterized assays of peroxisomal biochemical functions could add further value to these model systems [Gootjes et al., 2002; Wanders and Waterham, 2006; Watkins et al., 2010]. In the future, we believe cultured patient fibroblast and CHO cell model systems could be adapted for high-throughout drug screens to identify nonsense suppressor therapies and other drugs suitable for the treatment of peroxisomal disorders.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Christopher Austin and James Inglese at the National Institutes of Health for thoughtful advice and discussion. This study was supported by grant NS064572 awarded by the National Institute for Neurological Disorders and Stroke, National Institutes of Health, and GM072447 awarded by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, National Institutes of Health. This investigation was conducted in a facility constructed with support from Research Facilities Improvement Program Grant Number C06 (RR10600-01, CA62528-01, RR14514-01) from the National Center for Research Resources, National Institutes of Health.

Grant Information: Contract grant sponsor: NINDS, NIH; Contract grant number: NS064572 Contract grant sponsor: NIGMS, NIH; Contract grant number: GM072447

References

- Allen LA, Raetz CR. Partial phenotypic suppression of a peroxisome-deficient animal cell mutant treated with aminoglycoside G418. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:13191–13199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auld DS, Lovell S, Thorne N, Lea WA, Maloney DJ, Shen M, Rai G, Battaile KP, Thomas CJ, Simeonov A, Hanzlik RP, Inglese J. Molecular basis for the high-affinity binding and stabilization of firefly luciferase by PTC124. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:4878–4883. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909141107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auld DS, Thorne N, Maguire WF, Inglese J. Mechanism of PTC124 activity in cell-based luciferase assays of nonsense codon suppression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:3585–3590. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813345106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhuvanagiri M, Schlitter AM, Hentze MW, Kulozik AE. NMD: RNA biology meets human genetic medicine. Biochem J. 2010;430:365–377. doi: 10.1042/BJ20100699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjorkhem I, Sisfontes L, Bostrom B, Kase BF, Blomstrand R. Simple diagnosis of the Zellweger syndrome by gas-liquid chromatography of dimethylacetals. J Lipid Res. 1986;27:786–791. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braverman N, Chen L, Lin P, Obie C, Steel G, Douglas P, Chakraborty PK, Clarke JT, Boneh A, Moser A, Moser H, Valle D. Mutation analysis of PEX7 in 60 probands with rhizomelic chondrodysplasia punctata and functional correlations of genotype with phenotype. Hum Mutat. 2002;20:284–297. doi: 10.1002/humu.10124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braverman N, Steel G, Lin P, Moser A, Moser H, Valle D. PEX7 gene structure, alternative transcripts, and evidence for a founder haplotype for the frequent RCDP allele, L292ter. Genomics. 2000;63:181–192. doi: 10.1006/geno.1999.6080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braverman N, Zhang R, Chen L, Nimmo G, Scheper S, Tran T, Chaudhury R, Moser A, Steinberg S. A Pex7 hypomorphic mouse model for plasmalogen deficiency affecting the lens and skeleton. Mol Genet Metab. 2010;99:408–416. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2009.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clancy JP, Bebok Z, Ruiz F, King C, Jones J, Walker L, Greer H, Hong J, Wing L, Macaluso M, Lyrene R, Sorscher EJ, Bedwell DM. Evidence that systemic gentamicin suppresses premature stop mutations in patients with cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163:1683–1692. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.7.2004001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du M, Liu X, Welch EM, Hirawat S, Peltz SW, Bedwell DM. PTC124 is an orally bioavailable compound that promotes suppression of the human CFTR-G542X nonsense allele in a CF mouse model. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:2064–2069. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711795105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gootjes J, Mooijer PA, Dekker C, Barth PG, Poll-The BT, Waterham HR, Wanders RJ. Biochemical markers predicting survival in peroxisome biogenesis disorders. Neurology. 2002;59:1746–1749. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000036609.14203.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorgas K, Teigler A, Komljenovic D, Just WW. The ether lipid-deficient mouse: tracking down plasmalogen functions. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1763:1511–1526. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.08.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guthrie OW. Aminoglycoside induced ototoxicity. Toxicology. 2008;249:91–96. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2008.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hainrichson M, Nudelman I, Baasov T. Designer aminoglycosides: the race to develop improved antibiotics and compounds for the treatment of human genetic diseases. Org Biomol Chem. 2008;6:227–239. doi: 10.1039/b712690p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirawat S, Welch EM, Elfring GL, Northcutt VJ, Paushkin S, Hwang S, Leonard EM, Almstead NG, Ju W, Peltz SW, Miller LL. Safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetics of PTC124, a nonaminoglycoside nonsense mutation suppressor, following single- and multiple-dose administration to healthy male and female adult volunteers. J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;47:430–444. doi: 10.1177/0091270006297140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inglese J, Thorne N, Auld DS. Reply to Peltz et al: Post-translational stabilization of the firefly luciferase reporter by PTC124 (Ataluren) Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:E65. [Google Scholar]

- James PD, Raut S, Rivard GE, Poon MC, Warner M, McKenna S, Leggo J, Lillicrap D. Aminoglycoside suppression of nonsense mutations in severe hemophilia. Blood. 2005;106:3043–3048. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-03-1307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karaman MW, Houck ML, Chemnick LG, Nagpal S, Chawannakul D, Sudano D, Pike BL, Ho VV, Ryder OA, Hacia JG. Comparative analysis of gene-expression patterns in human and african great ape cultured fibroblasts. Genome Res. 2003;13:1619–1630. doi: 10.1101/gr.1289803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellermayer R, Szigeti R, Keeling KM, Bedekovics T, Bedwell DM. Aminoglycosides as potential pharmacogenetic agents in the treatment of Hailey-Hailey disease. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126:229–231. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerem E, Hirawat S, Armoni S, Yaakov Y, Shoseyov D, Cohen M, Nissim-Rafinia M, Blau H, Rivlin J, Aviram M, Elfring GL, Northcutt VJ, Miller LL, Kerem B, Wilschanski M. Effectiveness of PTC124 treatment of cystic fibrosis caused by nonsense mutations: a prospective phase II trial. Lancet. 2008;372:719–727. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61168-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linde L, Boelz S, Nissim-Rafinia M, Oren YS, Wilschanski M, Yaacov Y, Virgilis D, Neu-Yilik G, Kulozik AE, Kerem E, Kerem B. Nonsense-mediated mRNA decay affects nonsense transcript levels and governs response of cystic fibrosis patients to gentamicin. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:683–692. doi: 10.1172/JCI28523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malik V, Rodino-Klapac LR, Viollet L, Wall C, King W, Al-Dahhak R, Lewis S, Shilling CJ, Kota J, Serrano-Munuera C, Hayes J, Mahan JD, Campbell KJ, Banwell B, Dasouki M, Watts V, Sivakumar K, Bien-Willner R, Flanigan KM, Sahenk Z, Barohn RJ, Walker CM, Mendell JR. Gentamicin-induced readthrough of stop codons in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Ann Neurol. 2010;67:771–780. doi: 10.1002/ana.22024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Salgado C, Lopez-Hernandez FJ, Lopez-Novoa JM. Glomerular nephrotoxicity of aminoglycosides. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2007;223:86–98. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2007.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moser HW. Genotype-phenotype correlations in disorders of peroxisome biogenesis. Mol Genet Metab. 1999;68:316–327. doi: 10.1006/mgme.1999.2926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moser HW, Moser AB. Measurement of saturated very long chain fatty acids in plasma. In: Hommes FA, editor. Techniques in diagnostic human biochemical genetics: a laboratory manual. New York: Wiley-Liss; 1991. pp. 177–191. [Google Scholar]

- Mosmann T. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J Immunol Methods. 1983;65:55–63. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(83)90303-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motley AM, Brites P, Gerez L, Hogenhout E, Haasjes J, Benne R, Tabak HF, Wanders RJ, Waterham HR. Mutational spectrum in the PEX7 gene and functional analysis of mutant alleles in 78 patients with rhizomelic chondrodysplasia punctata type 1. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;70:612–624. doi: 10.1086/338998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peltz SW, Welch EM, Jacobson A, Trotta CR, Naryshkin N, Sweeney HL, Bedwell DM. Nonsense suppression activity of PTC124 (ataluren) Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:E64. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901936106. author reply E65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinotti M, Rizzotto L, Chuansumrit A, Mariani G, Bernardi F. Gentamicin induces sub-therapeutic levels of coagulation factor VII in patients with nonsense mutations. J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4:1828–1830. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.02057.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Politano L, Nigro G, Nigro V, Piluso G, Papparella S, Paciello O, Comi LI. Gentamicin administration in Duchenne patients with premature stop codon. Preliminary results. Acta Myol. 2003;22:15–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroers A, Kley RA, Stachon A, Horvath R, Lochmuller H, Zange J, Vorgerd M. Gentamicin treatment in McArdle disease: failure to correct myophosphorylase deficiency. Neurology. 2006;66:285–286. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000194212.31318.fc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sermet-Gaudelus I, De Boeck K, Casimir GJ, Vermeulen F, Leal T, Mogenet A, Roussel D, Fritsch J, Hanssens L, Hirawat S, Miller NL, Constantine S, Reha A, Ajayi T, Elfring GL, Miller LL. Ataluren (PTC124) induces CFTR protein expression and activity in children with nonsense mutation cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010 doi: 10.1164/rccm.201001-0137OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sermet-Gaudelus I, Renouil M, Fajac A, Bidou L, Parbaille B, Pierrot S, Davy N, Bismuth E, Reinert P, Lenoir G, Lesure JF, Rousset JP, Edelman A. In vitro prediction of stop-codon suppression by intravenous gentamicin in patients with cystic fibrosis: a pilot study. BMC Med. 2007;5:5. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-5-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg S, Chen L, Wei L, Moser A, Moser H, Cutting G, Braverman N. The PEX Gene Screen: molecular diagnosis of peroxisome biogenesis disorders in the Zellweger syndrome spectrum. Mol Genet Metab. 2004;83:252–263. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2004.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg S, Jones R, Tiffany C, Moser A. Investigational methods for peroxisomal disorders. Curr Protoc Hum Genet. 2008;Chapter 17 doi: 10.1002/0471142905.hg1706s58. Unit 17 16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg SJ, Dodt G, Raymond GV, Braverman NE, Moser AB, Moser HW. Peroxisome biogenesis disorders. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1763:1733–1748. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thieringer R, Raetz CR. Peroxisome-deficient Chinese hamster ovary cells with point mutations in peroxisome assembly factor-1. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:12631–12636. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorne N, Inglese J, Auld DS. Illuminating insights into firefly luciferase and other bioluminescent reporters used in chemical biology. Chem Biol. 2010;17:646–657. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2010.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Bosch H, Schutgens RB, Wanders RJ, Tager JM. Biochemistry of peroxisomes. Annu Rev Biochem. 1992;61:157–197. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.61.070192.001105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner KR, Hamed S, Hadley DW, Gropman AL, Burstein AH, Escolar DM, Hoffman EP, Fischbeck KH. Gentamicin treatment of Duchenne and Becker muscular dystrophy due to nonsense mutations. Ann Neurol. 2001;49:706–711. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wanders RJ. Peroxisomes, lipid metabolism, and peroxisomal disorders. Mol Genet Metab. 2004;83:16–27. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2004.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wanders RJ, Waterham HR. Biochemistry of mammalian peroxisomes revisited. Annu Rev Biochem. 2006;75:295–332. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.74.082803.133329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B, Yang Z, Brisson BK, Feng H, Zhang Z, Welch EM, Peltz SW, Barton ER, Brown RH, Jr, Sweeney HL. Membrane blebbing as an assessment of functional rescue of dysferlin-deficient human myotubes via nonsense suppression. J Appl Physiol. 2010;109:901–905. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01366.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins PA, Moser AB, Toomer CB, Steinberg SJ, Moser HW, Karaman MW, Ramaswamy K, Siegmund KD, Lee DR, Ely JJ, Ryder OA, Hacia JG. Identification of differences in human and great ape phytanic acid metabolism that could influence gene expression profiles and physiological functions. BMC Physiol. 2010;10:19. doi: 10.1186/1472-6793-10-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welch EM, Barton ER, Zhuo J, Tomizawa Y, Friesen WJ, Trifillis P, Paushkin S, Patel M, Trotta CR, Hwang S, Wilde RG, Karp G, Takasugi J, Chen G, Jones S, Ren H, Moon YC, Corson D, Turpoff AA, Campbell JA, Conn MM, Khan A, Almstead NG, Hedrick J, Mollin A, Risher N, Weetall M, Yeh S, Branstrom AA, Colacino JM, Babiak J, Ju WD, Hirawat S, Northcutt VJ, Miller LL, Spatrick P, He F, Kawana M, Feng H, Jacobson A, Peltz SW, Sweeney HL. PTC124 targets genetic disorders caused by nonsense mutations. Nature. 2007;447:87–91. doi: 10.1038/nature05756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weller S, Gould SJ, Valle D. Peroxisome biogenesis disorders. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2003;4:165–211. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.4.070802.110424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilschanski M, Famini C, Blau H, Rivlin J, Augarten A, Avital A, Kerem B, Kerem E. A pilot study of the effect of gentamicin on nasal potential difference measurements in cystic fibrosis patients carrying stop mutations. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161:860–865. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.3.9904116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilschanski M, Yahav Y, Yaacov Y, Blau H, Bentur L, Rivlin J, Aviram M, Bdolah-Abram T, Bebok Z, Shushi L, Kerem B, Kerem E. Gentamicin-induced correction of CFTR function in patients with cystic fibrosis and CFTR stop mutations. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1433–1441. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yik WY, Steinberg SJ, Moser AB, Moser HW, Hacia JG. Identification of novel mutations and sequence variation in the Zellweger syndrome spectrum of peroxisome biogenesis disorders. Hum Mutat. 2009;30:E467–480. doi: 10.1002/humu.20932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zingman LV, Park S, Olson TM, Alekseev AE, Terzic A. Aminoglycoside-induced translational read-through in disease: overcoming nonsense mutations by pharmacogenetic therapy. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2007;81:99–103. doi: 10.1038/sj.clpt.6100012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.