Abstract

Non-retroviral RNA virus sequences (NRVSs) have been found in the chromosomes of vertebrates and fungi, but not plants. Here we report similarly endogenized NRVSs derived from plus-, negative-, and double-stranded RNA viruses in plant chromosomes. These sequences were found by searching public genomic sequence databases, and, importantly, most NRVSs were subsequently detected by direct molecular analyses of plant DNAs. The most widespread NRVSs were related to the coat protein (CP) genes of the family Partitiviridae which have bisegmented dsRNA genomes, and included plant- and fungus-infecting members. The CP of a novel fungal virus (Rosellinia necatrix partitivirus 2, RnPV2) had the greatest sequence similarity to Arabidopsis thaliana ILR2, which is thought to regulate the activities of the phytohormone auxin, indole-3-acetic acid (IAA). Furthermore, partitivirus CP-like sequences much more closely related to plant partitiviruses than to RnPV2 were identified in a wide range of plant species. In addition, the nucleocapsid protein genes of cytorhabdoviruses and varicosaviruses were found in species of over 9 plant families, including Brassicaceae and Solanaceae. A replicase-like sequence of a betaflexivirus was identified in the cucumber genome. The pattern of occurrence of NRVSs and the phylogenetic analyses of NRVSs and related viruses indicate that multiple independent integrations into many plant lineages may have occurred. For example, one of the NRVSs was retained in Ar. thaliana but not in Ar. lyrata or other related Camelina species, whereas another NRVS displayed the reverse pattern. Our study has shown that single- and double-stranded RNA viral sequences are widespread in plant genomes, and shows the potential of genome integrated NRVSs to contribute to resolve unclear phylogenetic relationships of plant species.

Author Summary

Eukaryotic genomes contain sequences that have originated from DNA viruses and reverse-transcribing viruses, i.e., retroviruses, pararetroviruses (DNA viruses), and transposons. However, the sequences of non-retroviral RNA viruses, which are unable to convert their genomes to DNA, were until recently considered not to be integrated into eukaryotic nuclear genomes. We present evidence for multiple independent events of horizontal gene transfer from a wide range of RNA viruses, including plus-sense, minus-sense, and double-stranded RNA viruses, into the genomes of distantly related plant lineages. Some non-retroviral integrated RNA viral sequences are conserved across genera within a plant family, whereas others are retained only in a limited number of species in a genus. Integration profiles of non-retroviral integrated RNA viral sequences demonstrate the potential of these sequences to serve as powerful molecular tools for deciphering phylogenetic relationships among related plants. Moreover, this study highlights plants co-opting non-retroviral RNA virus sequences, and provides insights into plant genome evolution and interplay between non-reverse-transcribing RNA viruses and their hosts.

Introduction

Events of horizontal gene transfer (HGT) have been identified between various combinations of viruses and their eukaryotic hosts. HGT can occur during evolution in 2 inverse directions: “from host to virus” or “from virus to host.” In the host to virus direction, viral acquisition of host genes is observed as insertion of cellular genes for proteases (see [1] for review), ubiquitin [2], chloroplast protein [3] and heat-shock proteins [4], [5] into viral genomes. The virus to host direction involves endogenization of viral genes. Fossil sequences of viral origin, mostly from retroviruses, have been detected in many animal genomes. However, retrovirus sequences have not been identified in plants; instead, reverse-transcribing DNA viruses (pararetroviruses) have been identified. Although pararetroviral sequences have been found in some plant nuclear genomes [6], [7], [8], [9], only a limited number of integrated sequences are exogenized to launch virus infection; however, their cellular functions remain unclear in other examples.

In contrast, the sequences of non-retroviral RNA viruses were considered not to integrate into host chromosomes. However, recent reports identified endogenized genes of non-retroviral elements in mammals [10], [11], [12], [13]. Examples include the nucleocapsid protein (N) and nucleoprotein (NP) genes of bornaviruses and filoviruses, members of the negative-strand RNA virus group in the order Mononegavirales [11], [12], [14]. While some integrated N genes are expressed, their biological significance is unclear. Identification of these sequences contrasts with the lack of evidence for negative-strand RNA virus genome integration into plant genomes. Furthermore, RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) and capsid protein (CP) coding domains from a group of monopartite dsRNA viruses have been identified in yeast chromosomes, and while some of these viruses appear to be expressed, their biological significance has not been explored [15], [16], [17].

The white root rot fungus Rosellinia necatrix is a soil-borne phytopathogenic ascomycetous fungus that causes damages to perennial crops. An extensive search of a large collection of field fungal isolates (over 1,000) was conducted to identify dsRNA (mycoviruses) that may serve as virocontrol (biological control) agents. Approximately 20% of field isolates were infected with known or unknown viral strains [18], [19], [20]. During molecular characterization of these viruses, we identified a novel partitivirus termed Rosellinia necatrix partitivirus 2 (RnPV2) in an ill-defined R. necatrix strain. The family Partitiviridae contains members with small bi-segmented dsRNA genomes [21] that infect plants, fungi or protozoa. They are thought to replicate using virion-associated RdRp in the host cytoplasm, which are phylogenetically related to those from the picorna-like superfamily [22]. Surprisingly, the RnPV2 CP showed the highest level of sequence identity to an Arabidopsis thaliana gene, IAA/LEU resistant 2 (ILR2), which was previously shown to regulate the activity of the phytohormone auxin [23]. Combined with information regarding integrated mononegaviral sequences in animals, this finding generated significant interest in searching currently available genome sequence data for not only dsRNA but also negative-strand viral sequences. In October 2010, Liu et al. [24] reported similar results based on an extensive search conducted in 2009. This group identified sequences in the chromosomes of diverse organisms that may have been acquired from monopartite (totiviruses and related unclassified viruses) and bipartite dsRNA viruses (partitiviruses).

We further examined plant genome sequences available as of December 10, 2010 for integrated sequences of not only partitivirus genomes but also negative-, and positive-strand RNA viruses (Table S1). Combining database searches and molecular analyses led to the identification of multiple endogenized sequences related to partitiviruses, cytorhabdoviruses, varicosaviruses and betaflexiviruses in the genomes of a variety of plants including those from the families Solanaceae and Brassicaceae. For example, while some partitivirus-related sequences are conserved on the orthologous locus across some genera, e.g., Arabidopsis, Capsella, Turritis, and Olimarabidopsis within the family Brassicaceae, others are retained in only a few species within a single genus, Arabidopsis. A similar integration pattern was observed for a rhabdovirus-related sequence in the family Solanaceae. These profiles of occurrence can potentially resolve unclear phylogenetic relationships between plants. Our study demonstrates widespread endogenization of non-retroviral RNA virus sequences (NRVSs) including sequences of plant positive- and negative-strand RNA viruses for the first time. We have proposed a model of viral gene transfer, in which NRVSs are suggested to be a factor constituting plant genomes.

Results

The CP sequence from a novel mycovirus shows the highest identity to a plant functional gene product, ILR2

We determined the complete nucleotide (nt) sequence of the genome segments (dsRNA1 and dsRNA2) of a novel partitivirus, RnPV2, from the white root rot fungus Rosellinia necatrix, a soil-borne phytopathogenic ascomycetous fungus. DsRNA2 was found to be 1828 nt long, encoding a polypeptide of 483 amino acids (aa) (CP, 54 kDa). Low-level sequence similarities among CPs from Partitiviridae family members were observed using a BLASTP search with RnPV2 CP against non-redundant sequences available in the NCBI database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). Surprisingly, RnPV2 CP showed the highest degree of sequence similarity to ILR2 from Ar. thaliana. Notably, sequence similarities between RnPV2 CP and ILR2 were greater than those between the CP sequence from another mycovirus, Sclerotinia sclerotiorum partitivirus S (SsPV-S) and ILR2 noted previously [24]. ILR2 is known to regulate indole-3-acetic acid (IAA)-amino acid conjugate sensitivity and metal transport. An Ar. thaliana mutant with a single amino acid substitution in ILR2, known as ilr2-1, was shown to exhibit normal root elongation in the presence of a high concentration of exogenous IAA-leucine conjugates, which represses root elongation in wild-type lines [23].

RnPV2 CP-like sequences are conserved in some Brassicaceae spp. and Mimulus guttatus

Magidin et al. [23] identified 2 alleles of ILR2 in Ar. thaliana accessions (a long and a short allele) (Figure 1A). Although the authors confirmed ILR2 expression for only the WS ecotype (short allele), they determined that both short and long versions of ILR2 were functional. Given the similarity between ILR2 and RnPV2 CP sequences, we hypothesized that HGT occurred between the 2 organisms. Therefore, we assessed the extent to which ILR2 is conserved in plants. We used 3 approaches: BLAST search, genomic PCR, and Southern blot analyses. We first conducted an exhaustive BLAST (tblastn) search against genome sequence databases as described in the Materials and Methods. This search identified ILR2 homologs in Ar. lyrata and Mimulus guttatus (yellow monkey flower), which included both short and long versions of ILR2 homologs with modest levels of aa sequence identities (over 20%) to RnPV2 CP (Table S2, Figure 1A). Furthermore, a variety of partitivirus CP-related sequences with low-levels of aa sequence identities (approximately 20%) to RnPV2 CP were also detectable from genome sequences from other 17 plant species (Table 1). These sequences were classified into a total of 8 subgroups based on relatedness to best matched extant partitiviruses (Table 1). Their nomenclature is: AtPCLS1 (ILR2) is from Arabidopsis thaliana partitivirus CP-like sequence (PCLS) 1. Differently numbered PCLSs, referring to proteins potentially encoded by PCLSs, show the highest level of aa sequence identities to CPs encoded by different partitiviruses.

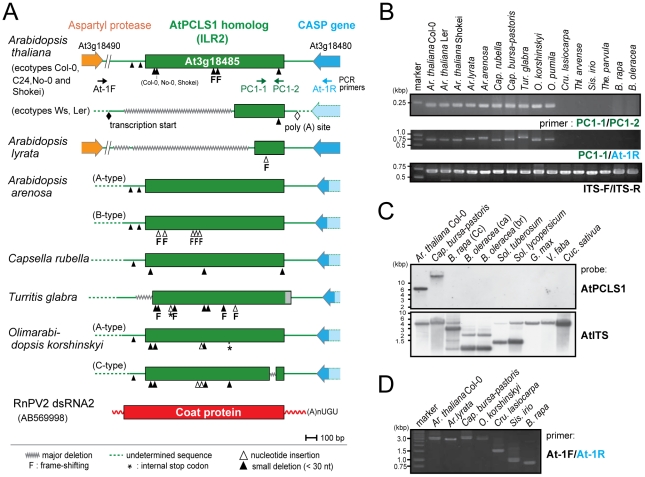

Figure 1. ILR2 (PCLS1) homologs from members of the family Brassicaceae.

(A) Schematic representation of RnPV2 CP-related ILR2 genes from Arabidopsis-related species. Green boxes refer to the coding regions of ILR2 homologs, while orange and blue thick arrows indicate those of cellular genes. Ar. thaliana Col-0, No-0, C24 and Shokei have long versions of ILR2, while those of the other Ar. thaliana ecotypes and Ar. lyrata have large deletions at the 5′-terminal portion. ILR2 homologs of Arabidopsis and closely related genera reside on the orthologous position. These plant homologs were most closely related to the CP gene of a fungal partitivirus, RnPV2. Symbols referring to mutations are shown at the bottom: waved line, major deletion; dashed line, undetermined sequence; open triangle, nucleotide insertion; filled triangle, small deletion (<30 nt); asterisk, internal stop codon; F, frame-shift; filled diamond, transcription start site; open diamond, poly(A) addition site. These symbols were utilized in this and subsequent figures. (B) Genomic PCR analysis of ILR2. The top and middle panels show amplification patterns with two primer sets (PC-1 and PC-2; PC-1 and At-1R). Primer positions and sequences are shown in Figure 1A and Table S3. A primer set, At-IRS-FW (ITS-F) and At-IRS-RV (ITS-R) [66], was used for amplification of the complete ribosomal internal transcribed spacer (ITS) regions 1 and 2 including the 5.8S rDNA. (C) Southern blotting of plant species in different families. Ten microgram of Eco RI-digested genomic DNA (per lane), except for that from Ar. thaliana Col-0 (2.5 µg/lane), was probed with a DIG-labeled ILR2 (top panel) or ITS DNA fragment (bottom panel) derived from Ar. thaliana Col-0. (D) Genomic PCR analysis of the ILR2-flanking region. PCR fragments were amplified by a primer set (At-1F and At-1R) on ILR2-carrying genomic DNAs from Ar. thaliana, Ar. lyrata, Cap. bursa-pastoris, and O. korshinskyi, and ILR2-non-carrying DNAs from Cru. lasiocarpa, Sis. irio, and B. rapa.

Table 1. Non-retroviral partitivirus CP-like sequences (PCLSs) identified in plant genome sequence databases.

| PCLS | Plant | Sequence ID | Database | Best-matched virus (abbreviation, segment) | e-value | Mol. analysisa |

| AtPCLS1 | Arabidopsis thaliana | At3g18485 (ILR2)b | NCBI | Rosellinia necatrix partitivirus 2 (RnPV2, dsRNA2) | 2e-47 | GP, GS, SQ, PA |

| AlPCLS1 | Arabidopsis lyrata | 929729 (XM_002885214) | Phytozome | Rosellinia necatrix partitivirus 2 (RnPV2, dsRNA2) | 4e-01c | GP |

| MgPCLS1 | Mimulus guttatus | mgv1a022511m.g | Phytozome | Rosellinia necatrix partitivirus 2 (RnPV2, dsRNA2) | 6e-39 | PA |

| AtPCLS2 | Arabidopsis thaliana | At4g14104b | NCBI | Raphanus sativus cryptic virus 2 (RSCV2, dsRNA2) | 3e-49 | GP, SQ |

| MePCLS2 d | Manihot esculenta | cassava4.1_029961m.g | Phytozome | Raphanus sativus cryptic virus 2 (RSCV2, dsRNA2) | 3e-42 | PA |

| AlPCLS3 | Arabidopsis lyrata | 352550 (XM_002872767) | Phytozome | Fragaria chiloensis cryptic virus (FCCV, dsRNA 2) | 5e-38 | GP, SQ |

| BrPCLS4 | Brassica rapa | Bra021820 | BRAD | carrot cryptic virus 1 (CaCV1, dsRNA2) | 3e-70 | GP, GS, SQ, PA |

| BoPCLS4 | Brassica oleracea | BH939664e | NCBI-gss | carrot cryptic virus 1 (CaCV1, dsRNA2) | 6e-47 | GP, GS, SQ, PA |

| BrPCLS5 | Brassica rapa | Bra020160b | BRAD | Raphanus sativus cryptic virus 1 (RSCV1, dsRNA2) | 2e-130 | GP, GS, SQ, PA |

| BoPCLS5 | Brassica oleracea | FI711962.1b | NCBI-gss | Raphanus sativus cryptic virus 1 (RSCV1, dsRNA2) | 3e-16 | GP, GS, SQ, PA |

| SpPCLS5 | Solanum phureja | unassigned (scaffold.20100818064734797543000) | PGSC | Raphanus sativus cryptic virus 1 (RSCV1, dsRNA2) | 8e-122 | PA |

| StPCLS5 | Solanum tuberosum | EI814115e | NCBI-gss | Raphanus sativus cryptic virus 1 (RSCV1, dsRNA2) | 5e-05 | GP, GS, SQ, PA |

| NtPCLS5-1 | Nicotiana tabacum | GSSb (Contig-1)f | NCBI-gss | Raphanus sativus cryptic virus 1 (RSCV1, dsRNA2) | 5e-106 | GP, GS, SQ, PA |

| NtPCLS5-2 | Nicotiana tabacum | GSSb (Contig-2)f | NCBI-gss | Raphanus sativus cryptic virus 1 (RSCV1, dsRNA2) | 2e-64 | GP, GS, SQ |

| NtPCLS6 | Nicotiana tabacum | GSSb (Contig-3)f | NCBI-gss | Fragaria chiloensis cryptic virus (FCCV, dsRNA3) | 1e-33 | GP, GS, SQ |

| VuPCLS6 | Vigna unguiculata | EI930635c | NCBI-gss | Fragaria chiloensis cryptic virus (FCCV, dsRNA3) | 1e-05 | - |

| GmPCLS6 | Glycine max | unassigned (WGS ACUP01011070,984-1304) | NCBI-wgs | Fragaria chiloensis cryptic virus (FCCV, dsRNA3) | 8e-10 | - |

| NtPCLS7 | Nicotiana tabacum | GSSb (Contig-4)f | NCBI-gss | Raphanus sativus cryptic virus 3 (RSCV3, dsRNA2) | 9e-06 | GP, GS, SQ |

| MtPCLS7 | Medicago truncatula | GSSb (Contig-1)f | NCBI-gss | Raphanus sativus cryptic virus 3 (RSCV3, dsRNA2) | 2e-17 | GP, SQ |

| MdPCLS7 | Malus x domestica | unassigned (wgs ACYM01118643, 10505-11776) | NCBI-wgs | Raphanus sativus cryptic virus 3 (RSCV3, dsRNA2) | 4e-46 | PA |

| LjPCLS8 | Lotus japonicus | AP010106e | NCBI-htgs | rose cryptic virus (RoCV, dsRNA 3) | 6e-63g | GP, SQ |

| PdPCL8 | Phoenix dactylifera | unassigned (wgs ACYX01071982, 560-268; 790-1379) | NCBI-wgs | rose cryptic virus (RoCV, dsRNA 3) | 2e-24 | - |

| SbPCL8 | Sorghum bicolor | unassigned (wgs ABXC01001628, 27853-28723) | NCBI-wgs | rose cryptic virus (RoCV, dsRNA 3) | 1e-40 | PA |

| ZmPCLS8 d | Zea mays | GSSb (Contig-1)f | NCBI-gss | rose cryptic virus (RoCV, dsRNA 3) | 7e-09 | - |

Molecular analysis carried out in this study: GP, genomic PCR; GS, genomic Southern blot; SQ, sequencing; PA, phylogenetic analysis; -, not performed.

Reported as non-retroviral integrated plant genome sequence by Liu et al. (2010).

AlPCLS1 shows an e-value, 3e-35 against AtILR2.

MePCLS2 in cassava and ZmPCLS8 in maize were found in intron of particular gene loci.

Reported as the candidates for non-retroviral integrated plant genome sequence in Liu et al. (2010).

Contig1-4 indicate GSS assembly sequences as described by Liu et al. (2010).

An unrelated sequence interrupting the virus-like sequence (Figure S1A) was removed for BLAST search.

Genomic PCR analysis with primers corresponding to highly conserved 240-bp portions revealed that ILR2 homologs were retained in genera closely related to Arabidopsis, such as Capsella, Turritis, and Olimarabidopsis, but not in members of distantly-related genera, Brassica, Thellungiella, Crucihimalaya, Sisymbrium, and Thlaspi within the Brassicaceae family (Figure 1B). Genomic PCR fragments covering the entire ILR2-like domains of the plants shown in Table S4 were sequenced directly or after cloning into a plasmid. It should be noted that PCLS1s of closely related genera reside in an orthologous position [25], i.e., in a convergent configuration with the gene for the transmembrane Golgi matrix protein AtCASP, which shares a high degree of sequence similarity across kingdoms [26]. This notion was confirmed by genomic PCR in which a primer pair allowed detection of 0.75- to 1-kb fragments spanning the CASP gene. Previous comparative genomics studies proposed a hypothesis that the Brassicaceae genomes consist of 24 (A to X) conserved genome blocks [27]. The ILR2 locus is on block F which is considered to be duplicated in B. rapa. A search against the Brassica database (BRAD) confirmed the absence of a PCLS1 on the 2 B. rapa loci that flank the CASP gene. Southern blotting with members of the Brassicaceae, Cucurbitaceae, Solanaceae, and Leguminosae families indicated that PCLS1 (ILR2) is present in Ar. thaliana and Cap. bursa-pastoris, but absent in the other plants (Figure 1C), consistent with BLAST results and genomic PCR analyses. Furthermore, the absence of ILR2 in Crucihimalaya lasiocarpa, Sisymbrium irio and B. rapa was confirmed by sequence analysis of genomic PCR fragments covering the entire ILR2 region and its flanking regions (Figure 1D).

Prevalence of partitivirus CP-like sequences (PCLS1 to PCLS8) in plant chromosomes

Genome sequences with low levels of similarities to RnPV2 CP included a number of PCLSs from various plants spanning more than 17 species from 8 families (Table 1). Most PCLSs confirmed to be present on their chromosomes of these organisms were identified by genomic PCR and/or Southern blotting and sequencing (Tables 1, S4). For instance, AtPCLS2 and Ar. lyrata PCLS3 (AlPCLS3) are retained on non-orthologous loci of ILR2s of Ar. thaliana and Ar. lyrata, respectively (Figure 2A). AtPCLS2 (At4g14104) resides between the genes for COP9 (constitutive photo-morphogenic-9, COP9) and an F-box protein, while AlPCLS3 is between 2 coding sequences for F-box domains corresponding to At4g02760 and At4g02740 [25]. AtPCLS2 and AlPCLS3 from 2 closely related plant species show the highest sequence identities to the CPs from 2 different partitiviruses: Raphanus sativus cryptic virus 2 (RSCV2) and Fragaria chiloensis cryptic virus (FCCV) (dsRNA2) [28]. The PCLS retention profile was revealed by genomic PCR using 2 primer sets. A primer set designed to amplify internal AtPCLS2 sequences provided DNA fragments of an expected size of 470 bp in Ar. thaliana accessions Col-0, Ler, and Shokei, but not in Ar. lyrata, Ar. Arenosa, or Cap. rubella (Figure 2B, top panel). A different primer set specific for AtPCLS2 and the F-box protein gene (At4g14103) gave the same amplification pattern (Figure 2B, second panel) as shown in the top panel. Using the same approach with 2 sets of primers, PCLS3 was detected by genomic PCR in Ar. lyrata and Ar. arenosa, while no such sequence was observed in Ar. thaliana ecotypes or Cap. rubella (Figure 2B, third and fourth panels). Although the COP9 and the F-box protein genes are conserved on the corresponding loci of Ar. lyrata, no counterpart of AtPCLS2 was identified between the genes (Phytozome). Similarly, no AlPCLS3 homolog was observed on the corresponding chromosomal position of Ar. thaliana [25].

Figure 2. PCLS2 and PCLS3 homologs from members of the genus Arabidopsis.

(A) Diagrams of the plant genome map containing PCLS2 and PCLS3 from Arabidopsis-related species. See Figure 1 legend for explanation of symbols. AtPCLS2 and AllPCL3 showed the highest levels of similarity to the CP of plant partitiviruses, Raphanus sativus cryptic virus 2 (RSCV2) and Fragaria chiloensis cryptic virus (FCCV), respectively. (B) Genomic PCR analysis of PCLS2 and PCLS3. PCLS2 homologs were amplified using primer sets PC2-1 and PC2-2 (top panel) and PC2-1 and At-2 (second panel). These primers are specific for AtPCLS2 except for At-2, which corresponds to an F-box protein gene (At4g14103). The third and fourth panels show amplification patterns of PCLS3 with primer sets PC3-1 and PC3-2 or Al-3 and PC3-2, respectively. A primer set, At-IRS-FW and At-IRS-RV (ITS-F and ITS-R for abbreviation, see the Figure 1 legend) were used in this and subsequent figures (Figures 3, 5, S1, S3) for amplification of the complete ITS regions. Primers' positions are shown by small arrows in A, while their sequences are shown in Table S3.

PCLS4 and PCLS5 were found in the genome sequence databases of B. rapa (BrPCLS4 and 5), Solanum phureja (wild species of potato) (SpPCLS5) (Figure 3A, S2), and Nicotiana tabacum (NtPCLS5-1 and -2) (Figure S1A). These sequences commonly exhibited greater sequence similarity to CPs of previously reported plant partitiviruses than to RnPV2 CP (Tables 1). The 3 PCLS5s from the Solanaceae family were very similar to each other (approximately 60% aa sequence identity), and showed high sequence identity (over 45%) (Table S2) to CP of Raphanus sativus cryptic virus 1 (RSCV1, plant partitivirus) [29]. Two PCLSs, BrPCLS4 (Bra021820) and BrPCLS5 (Bra020160), which are detected on different scaffolds, were determined to not flank the CASP gene of B. rapa as AtPCLS1 (ILR2) does. BrPCLS4 and 5 show much greater aa sequence identities to CPs of RSCV1 and carrot cryptic virus 1 (CaCV1, plant partitivirus) [30] than it does to RnPV2 CP (Table S2).

Figure 3. PCLS4 and PCLS5 homologs from members of the families Solanaceae and Brassicaceae.

(A) Diagrams of the structures of B. rapa PCLS4 (BrPCLS4), and PCLS5s from Sol. phureja (SpPCLS5) and from B. rapa (BrPCLS5). PCLS4 shows the highest similarities to carrot cryptic virus 1 (CaCV1) CP, while PCLS5s exhibit the greatest sequence similarities to the CP of another plant partitivirus, Raphanus sativus cryptic virus 1 (RSCV1). (B) Genomic PCR analysis of PCLS4 and PCLS5. Genomic DNA from members of the families Brassicaceae and Solanaceae shown on the top of gels were used for amplification of PCLSs. Primers used were: PC4-1 and PC4-2 specific for BrPCLS4 (top panel); PC5a-1 and PC5a-2 specific for BrPCLS5 (second panel); PC5b-1 and PC5b-2 specific for SpPCLS5 (third panel); PC5b-1 and SP-5 specific for SpPCLS5 and PUX_4 (fourth panel); ITS-F and ITS-F specific for the ITS region (bottom panel). (C) Genomic Southern blotting of PCLS4 and PCLS5. EcoRI-digested genomic DNA isolated from various plants shown at the top of the blots were hybridized with different DIG-labeled probes specific for BrPCLS4 (top panel), BrPCLS5 (second panel), B. rapa ITS (third panel) Sol. tuberosum PCLS5 (fourth panel) and Sol. tuberosum ITS (bottom panel). Migration positions of DNA size standards are shown at the left.

Molecular analyses were performed to determine how widely these PCLS4 and PCLS5 are conserved. Genomic PCR using a primer set specific for BrPCLS4 detected related sequences in all Brassica species tested, but not in other plants including members of the family Solanaceae or genera other than Brassica in Brassicaceae, such as Ar. thaliana, Cru. lasiocarpa, Thellungiella parvula, Thl. arvense and Sis. irio, and Raphanus sativus (Figure 3B, top panel). For BrPCLS5, the primer set, PC5a-1 and PC5a-2 enabled detection of expected PCR fragments in all Brassica plants in addition to R. sativus, while no PCR fragments were amplified in the other plant species (Figure 3B, second panels). A different detection profile was obtained by genomic PCR with a primer set specific for SpPCLS5 in which PCLS5-related sequences were detectable only in Sol. tuberosum and Sol. lycopersicum (Figure 3B, third and fourth panels). We failed to yield amplification from all other tested plants in the families Brassicaceae and Solanaceae including Sol. melongena. Interestingly, PCLS5, but not PCLS4 fragments, were detected in R. sativus. Moreover, the presence or absence of PCLSs was confirmed by genomic Southern analysis. As expected from the genomic PCR results, hybridization signals were detected with a BrPCLS4- or a BrPCLS5-specific probe in the Brassica species such as B. rapa and B. oleracea (Figure 3C, top and second panels); however, the numbers and signal positions differed between the 2 blots. The StPCLS4-specific probe allowed detection of 2 and 1 hybridization signals in Sol. tuberosum and Sol. lycopersicum, respectively, but not in any other plants examined in this study (Figure 3C, fourth panel).

In addition to PCLS1 to PCLS5, 2 other subgroups of PCLSs (PCLS6 and PCLS7) were observed in the GSS database of N. tabacum and showed an interesting detection pattern in Nicotiana species (Figure S1). NtPCLS6 and NtPCLS7 showed moderate aa sequence identities to CPs encoded by FCCV dsRNA3 (38%) [28] and RSCV3 dsRNA2 (30%) [29], respectively. Sequencing of genomic PCR fragments and Southern blotting (Figure S1B, E) suggested that NtPCLS5-1 and NtPCLS5-2 are retained only in N. tabacum, but not in other Nicotiana species examined, such as N. benthamiana and N. megalosiphon, whereas PCLS6 was detected in both N. tabacum and N. megalosiphon (Figure S1B). In contrast, PCLS7 is conserved in all 4 Nicotiana plants tested, although sequence divergence was observed among the PCLS7s. Other PCLSs from 2 legume plants, MtPCLS7 and LjPCLS8 were identified on their nuclear genomes by PCR (Figures S1A, C, D).

Phylogenetic analysis of the PCLSs

An expanded BLAST (tblastn) search against the EST sequence libraries (in NCBI) helped detect many related sequences of possible plant partitiviruses that shared moderate levels of sequence similarity. Some representative EST sequences, PCLSs and partitivirus CPs, whose entire sequences are available, were aligned using the MAFFT program. Three relatively well-conserved motifs are located on the N- terminal, central, and C-terminal regions of partitivirus CPs and PCLSs, and are represented by PGPLxxxF [31], F/WxGSxxL and GpfW domains (Figure S2). As expected from sequence similarities, phylogenetic analysis of partitivirus CPs and PCLSs identified in plant genomes clearly show that members of each PCLSs subgroup (PCLS1, 2, 4, 5, 7, 8) clusters together with the CP of the respective partitivirus that shows the highest sequence similarities (Figure 4, Table 1). For example, RnPV2 CP (in red), MgPCLS1, and ILR2 homologs (PCLS1s) from Arabidopsis-related genera (in green) constitute one group in the tree. The MgPCLS1 clade includes an assembled sequence in the EST database from meadow fescue (Festuca pratensis) (in purple) believed to be from a plant partitivirus. Another group includes PCLS5s from the families Brassicaceae and Solanaceae (in green), CPs of fungal (in red) and plant partitiviruses (in blue) are grouped together. Within this group, PCLSs from the families Brassicaceae (BrPCLS5, BoPCLS5, and BnPCLS5) and Solanaceae (StPCLS5, SpPCLS5, SlPCLS5, and NtPCLS5-1) comprised 2 subgroups that included CPs encoded by RSCV1 (CP) and RSCV1 dsRNA3 (Figure 4), respectively, which are considered to be from two different partitiviruses. PCLS4s from members of the genus Brassica clustered together with CPs of other plant partitiviruses including white clover cryptic virus 1 (WCCV1) [32], CaCV1, beet cryptic virus 1 (BCV1) [33], and vicia cryptic virus (VCV) [34].

Figure 4. Molecular phylogenetic analysis of partitivirus CPs and plant PCLSs.

A phylogenetic tree was generated based on an alignment (see Figure S2) of the entire region of partitivirus CP-related sequences. Analyzed sequences were from 7 fungal partitiviruses (shown in red), 10 plant partitiviruses (in blue), 1 F. pratensis EST-derived sequence (shown in purple), 4 accessions of Ar. thaliana, and 16 other plant species (in green) (See Tables 1 and S4 for their descriptions). The assembled sequence from the F. pratensis ESTs in the database is believed to be of plant-infecting partitivirus origin because the library contains EST entries of RdRp sequences and some had interrupted poly(A) tails typical of a partitiviral mRNA. Viruses analyzed phylogenetically are: Rosellinia necatrix partitivirus 2, RnPV2; Sclerotinia sclerotiorum partitivirus S, SsPV-S; Chondrostereum purpureum cryptic virus, CPCV; Raphanus sativus cryptic virus 1, RSCV1; white clover cryptic virus 1, WCCV1; vicia cryptic virus, VCV; carrot cryptic virus 1, CaCV1; beet cryptic virus 1, BCV1; Amasya cherry disease associated partitivirus, ACD-PV; cherry chlorotic rusty spot-associated partitivirus, CCRS-PV; Heterobasidion RNA virus 3, HetRV3; Flammulina velutipes browning virus, FvBV; beet cryptic virus 2, BCV2; Raphanus sativus cryptic virus 3, RSCV3; Fragaria chiloensis cryptic virus, FCCV; rose cryptic virus 1, RoCV; Raphanus sativus cryptic virus 2, RSCV2. Note that RSCV1 CP gene and RSCV1 dsRNA3, BCV2 dsRNA2 and 3, and RSCV2 dsRNA2 and 3 are assumed to be from two independent viruses although the same virus name was assigned to the segments in the database. Numbers at the branches show aLRT values using an SH-like calculation (only values greater than 0.5 are shown). The scale bar represents the relative genetic distance (number of substitutions per nucleotide).

The tree topology shown in Figure 4 was similar to that reported by Liu et al. [24]. The current study used more PCLSs detected in various plants but not partial PCLSs such as PCLS3 and NtPCLS5-2, 6 and 7 (Tobacco Contig-2, -3 and -4) analyzed phylogenetically by Liu et al. [24].

Detection of negative-strand RNA viral sequences in plant nuclear genomes

Because negative-strand RNA viral sequences are found in animal chromosomes, we searched for negative-strand RNA viral sequences (Table S1) in plant genomes as described in the Materials and Methods. This search identified sequences related to the N protein in members of the genus Cytorhabdovirus (Lettuce necrotic yellows virus, LNYV, Lettuce yellow mottle virus, LYMoV, and northern cereal mosaic virus, NCMV) and a CP of the genus Varicosavirus (Lettuce big-vein associated virus, LBVaV) in the genomes of a variety of plants such as Populus trichocarpa, N. tabacum, and B. rapa (Figures 5, S3, Table 2). While varicosaviruses have bipartite genomes replicated in the cytoplasm of infected plant cells, they are phylogenetically closely related to cytorhabdoviruses with monopartite genomes [35], [36]. Varicosavirus CP is phylogenetically and functionally equivalent to rhabdovirus N. Thus, these plant nuclear sequences were designated as rhabdovirus N-like sequences (RNLSs) and classified into 4 subgroups (RNLS1 to RNLS4) based on the sequences of presently existing viruses with the highest levels of sequence similarities (Table 2). Their potentially encoding proteins were designated as RNLSs as in the case for PCLSs.

Figure 5. Negative-strand RNA virus-related sequences (RNLSs) from plant nuclear genomes.

(A) Genome organization of a varicosavirus, lettuce big-vein associated virus (LBVaV) [67] and a cytorhabdovirus, lettuce necrotic yellows virus (LNYV) [68]. While LBVaV and LNYV have a bipartite and a monopartite genome architecture, respectively, both viruses share similarities in terminal sequence features such as leader sequences (le) and trailer sequence (tr), genome expression strategy and sequences in encoded proteins (e.g., CP vs. N and L vs. L). (B) Schematic representation of RNLSs and their flanking regions. RNLS found in the genome sequence database of B. rapa (BrRNLS1) is shown to match that of CP from LBVaV. Another RNLS from N. tabacum (NtRNLS2) showed the greatest similarity to the LNYV-N protein. (C, E) Genomic PCR analysis of RNLS1 and RNLS2. Template genomic DNAs from plant species shown on the top of the gel were used to amplify RNLS1 (C, top panel), RNLS2 (E, top panel) or ribosomal RNA ITS regions (C and E, bottom panels). Primer pairs, RN1a-1 and RN1a-2, RN2-1 and RN2-2, and ITS-F and ITS-R were used to amplify RNLS1, RNLS2, and the ITS regions, respectively. Amplified DNA fragments were electrophoresed in 1.0% agarose gel in TAE. (D, F) Southern blot analyses of plant species in different families. The same DNA preparations as for Figure 1 were used for detection of RNLS1 (D) and RNLS2 (F) in which DIG-labeled DNA fragments spanning BrRNLS1, NtRNLS2, and N. tabacum ITS served as probes, respectively. See Figure 3C for hybridization with a B. rapa ITS DNA probe.

Table 2. Rhabdovirus nucleocapsid protein (N)-like sequences (RNLSs) identified in plant genome sequence databases.

| RNLS | Plant | Sequence ID | Database | Best-matched virus (abbreviation) | e-value | Mol. analysisa |

| BrRNLS1-1 | Brassica rapa | Bra027743 | BRAD | lettuce big-vein associated virus (LBVaV) | 9e-08 | GP, GS, SQ, PA |

| AqcRNLS1 | Aquilegia coerulea | AcoGoldSmith_v1.007196m | Phytozome | lettuce big-vein associated virus (LBVaV) | 2e-20 | (GP, SQ) PA |

| MdRNLS1-1 | Malus x domestica | unassigned (wgs ACYM01021736, 2134-3297) | NCBI-wgs | lettuce big-vein associated virus (LBVaV) | 8e-31 | GP, SQ, PA |

| MdRNLS1-2 | Malus x domestica | unassigned (wgs ACYM01114737, 2849–3310) | NCBI-wgs | lettuce big-vein associated virus (LBVaV) | 7e-16 | GP, SQ |

| LjRNLS1-1 | Lotus japonicus | unassigned (gss BABK01031243+cDNA AK339012) | NCBI-gss,-nt | lettuce big-vein associated virus (LBVaV) | 6e-12, 7e-13 | GP, SQ, PA |

| LjRNLS1-2 | Lotus japonicus | unassigned (chromosome 3 clone LjT47I22, 60953-62007) | NCBI-htgs | lettuce big-vein associated virus (LBVaV) | 2e-16 | GP, SQ, PA |

| CsRNLS1 | Cucumis sativus | unassigned (wgs ACHR01010215, 16588–18054) | NCBI-wgs | lettuce big-vein associated virus (LBVaV) | 1e-05 | GP, SQ, PA |

| TcRNLS1 | Theobroma cacao | unassigned (wgs CACC01021584, 28267-27932) | NCBI-wgs | lettuce big-vein associated virus (LBVaV) | 1e-03 | - |

| MgRNLS2 | Mimulus guttatus | mgf014425m | Phytozome | lettuce necrotic yellows virus (LNYV) | 8e-07 | - |

| NtRNLS2 | Nicotiana tabacum | GSS (Contig-5, Figure S3) | NCBI-gss | lettuce necrotic yellows virus (LNYV) | 8e-35 | GP, GS, SQ, PA |

| NtRNLS3 | Nicotiana tabacum | GSS (Contig-6, Figure S3) | NCBI-gss | northern cereal mosaic virus (NCMV) | 8e-08 | GP, SQ |

| PtRNLS4 | Populus trichocarpa | POPTR_0008s16330 | Phytozome | lettuce yellow mottle virus (LYMoV) | 1e-41 | PA |

Molecular analysis carried out in this study: GP, genomic PCR; GS, genomic Southern blot; SQ, sequencing; PA, phylogenetic analysis; -, not performed.

To confirm the presence of the RNLSs in plant chromosomes, we conducted genomic PCR and Southern blot analyses. Interestingly genomic PCR with primers specific for an RNLS1 from B. rapa (BrRNLS1) detected RNLS1s in R. sativus and all tested plants within the Brassica genus, but not in members in other genera (Figure 5C), in a pattern similar to that of PCLS5s from the family Brassicaceae (Figure 3B). Consistent with these results, Southern blotting detected hybridization signals in 3 Brassica plants (Figure 5D) with a probe specific for BrRNLS1.

The NtRNLS2 sequence was detected in N. tabacum, while no fragments were generated from other Nicotiana species using genomic PCR (Figure 5E). Southern blotting results supported this detection profile (Figure 5F); N. tabacum, but not N. benthamiana, was shown to carry an NtRNLS2-related sequence (Figure 5F, left panel).

All other RNLSs discovered through the similarity search of genome sequence databanks (Table 2), except for PtRNLS4 from Pop. trichocarpa and TcRNLS1 from Theobroma cacao, were shown to be retained on respective plant genomes by genomic PCR and subsequent sequencing (Figure S3). RNLS1s molecularly analyzed included those from Aquilegia flabellata (a close relative of Aq. coerulea) (AfRNLS1), Lotus japonicus (LjRNLS1), Malus x domestica (MdRNLS1) and Cucumis sativus (CsRNLS1) (Figure S3B–H). The AqfRNLS1 sequence defined in this article showed approximately 98% nt sequence identity to AcRNLS1 whose sequence is available in the database (Phytozome). LjRNLS1-1 from L. japonicus line B129 and CsRNLS1 from 3 cucumber varieties (Hokushin, Suyo, and ‘Borszcagowski’ line B10) were identical to the reported RNLS1 sequences for line MG-20 (Kazusa DNA Research Institute) and ‘Chinese long’ line 9930 [37], respectively. Approximately 97% nucleotide sequence identity was found between MdRNLS1s of cultivars ‘Sun-Fuji’ and ‘Golden Delicious.’ ‘Golden Delicious’ is currently used in the apple genome sequence project [38] (http://www.rosaceae.org/projects/apple_genome). These examined RNLS sequences are listed in Table S5.

Phylogenetic analysis of negative-strand RNA virus sequence in plant nuclear genomes

Several sequences found through searching plant EST databases (Table S6, Figure S4) were included in our phylogenetic analysis. Deduced amino acid sequences of plant RNLSs, the N (CP) proteins of negative-strand RNA viruses, and related EST entries were aligned using the MAFFT program (Figure S5). Pair-wise similarities between selected RNLSs and viral N (CP) sequences are shown in Table S7. Two amino acid segments, GmH and YaRifdxxxfxxLQtkxC are relatively well-conserved among these sequences. A dendrogram generated on the basis of alignment showed 4 major groups containing plant RNLSs (Figure 6). RNLS1s are separated into two major groups. The first group includes varicosavirus CPs and RNLS1s from apple, cucumber and Brassica plants (MdRNLS1, CsRNLS1, BoRNLS1, and BrRNLS1) in addition to a few ESTs. The second group accommodates RNLS1s from Aquilegia and Lotus (AqfRNLS1, AqcRNLS1, LjRNLS1), together with an RNLS2 from Mim. guttatus (MgRNLS2) and EST sequences from Cichorium intybus and B. oleracea. The placement of MgRNLS2 in this group may be explained by low-level sequence identity to its most closely related extant varicosavirus, LNYV (Table 2). NtRNLS3, PtRNLS4, and Ns of cytorhabdoviruses (LNYV, LYMoV, and NCMV) form the third group (Figure 6). A dichorhabdovirus (orchid fleck virus, OFV) and nucleorhabdoviruses (PYDV and SYNV), replicating in the nuclei of host plants, are placed into an independent clade.

Figure 6. Phylogenetic analyses of the nucleocapsid protein sequences of rhabdoviruses and RNLSs.

Phylogenetic relation of nucleocapsid proteins of negative strand RNA viruses and plant RNLSs. A phylogenetic tree was constructed using PhyML 3.0 based on the multiple amino acid sequence alignments of entire regions of rhabdovirus nucleocapsid protein-related sequences shown in Figure S5. Plant RNLSs, N (CP) proteins from negative-strand RNA viruses, and EST-derived sequences are shown in green, blue and purple, respectively. Viruses analyzed phylogenetically are: tobacco stunt virus, TStV; lettuce big-vein associated virus, LBVaV; lettuce yellow mottle virus, LYMoV; lettuce necrotic yellows virus, LNYV; northern cereal mosaic virus, NCMV; potato yellow dwarf virus, PYDV; orchid fleck virus, OFV; sonchus yellow net virus, SYNV. Numbers at the branches show aLRT values using an SH-like calculation (only values greater than 0.5 are shown).

Whether most of the analyzed ESTs originated from viruses or plant chromosomes is unknown. However, an EST from F. pratensis is presumed to originate from a plant virus in our preliminary experiment not only because the N (CP)- but also the L (RdRp)-derived ESTs were detected in the same EST library of F. pratensis. This suggests a presently existing virus more closely related to RNLSs of the genus Brassica than LBVaV, because both N- and L-related sequences are rarely found in a single plant genome (Table 2).

Database search for and molecular detection of plus-strand RNA viral sequences in plant genomes

Extensive searches of genome sequence databases for plant plus-strand RNA viral sequences were conducted using genome sequences of various plus-strand RNA viruses representing the major virus genera and families Potyviridae, Luteoviridae, Tombusviridae, and Bromoviridae (Table S1). Compared to searches for double- or negative-strand RNA viral sequences, the search for plus-strand RNA virus sequences yielded a much smaller number of hits. The Medicago truncatula database (HTGS) contains sequences of 320 and 475 nts with over 98% sequence identity to the capsid and movement protein genes of cucumber mosaic virus, a member of the family Bromoviridae. However, this sequence was not amplified in Med. truncatula line A17 used in the genome sequence project by genomic PCR with different sets of internal and external primers. A sequence similar to replication-related genes of citrus leaf blotch virus (CLBV) [39] belonging to the family Betaflexiviridae, is identified in the complete genome databases for the cucumber ‘Chinese long’ line 9930 [37] and termed Cucumis sativus flexivirus replicase-like sequence 1, CsFRLS1 (Figure 7A). The GSS database of cucumber ‘Borszczagowski’ line B10 also contains CsFRLS1 (http://csgenome.sggw.pl/), but its available sequence is fragmented (Figure 7A, dashed purple bar) and shorter than that in the complete genome sequence data base.

Figure 7. Plant genome sequence related to positive-strand RNA virus.

(A) Chromosomal position of the flexivirus replicase-like sequence (FRLS) found in the cucumber ‘Chinese long’ inbred line 9930 and the genome structure of a positive-sense RNA virus, citrus leaf blotch virus (CLBV) [39]. A sequence related to the 5′ terminal half of the CLBV genome (CsFRLS1) is detected in scaffold 507. Genes for small potential ORFs (Cucsa 038520 and 038540) reside near CsFRLS1 as well as a retrotransposon-like sequence (shown by thick black lines). Three short sequences identical to CsFRLS1 are found in the GSS database (NCBI) from a different cucumber line, ‘Borszczagowski’ B10 (http://csgenome.sggw.pl/) (shown by dashed bars above CsFRLS1 in red). Functional domains of the CLBV replicase polyprotein are indicated in ocher: Met, methyltransferase; AlkB, Fe(II)/2OG-dependent dioxygenase superfamily domain; peptidase; Hel, RNA helicase; RdRp, RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. (B) Detection of CsFRLS1 from cucumber line by genomic PCR. See Materials and Methods for DNA isolation and PCR reaction. Template genomic DNA was prepared from the cucumber cultivar ‘Borszczagowski’ line B10 (top panel) and Citrullus lanatus (watermelon) (bottom panel). Primers (FR1-1 to FR1-6, FR1-6*, CS-1F, and CS-1R) used are shown on the top of the panel. The positions of the primers are shown by arrows below CsFRLS1 in A, except primer pairs used for amplification of the ITS region (ITS-F and ITS-R) (Table S3). (C) Phylogenetic analysis of CsFRLS1. CsFRLS1 and corresponding amino acid sequences from plant flexiviruses including members of the genera Citrivirus, Carlavirus, Foveavirus, Vitivirus, Capillovirus, Trichovirus and Potexvirus, were aligned using MAFFT program (Figure S6). The alignment was then utilized to generate a phylogram. Numbers at the branches show aLRT values using an SH-like calculation (only values greater than 0.5 are shown).

Two independent cucumber genome databases for 2 different lines strongly suggest the presence of CsFRLS1 in the cucumber chromosome. We confirmed this by genomic PCR using different sets of primers corresponding to methyltransferase (Met) and RNA helicase (Hel) domains, the inter-domain region (FR1-3 and FR1-4) and the entire CsFRLS1 region (Figure 7B). DNA fragments of expected sizes were amplified on genomic DNA from the ‘Borszczagowski’ line B10, but not from watermelon, Citrullus lanatus (Figure 7B). Furthermore, genomic PCR fragments covering FRLS1 and its flanking putative open reading frames (ORFs) were amplified, strongly suggesting that FRLS1 resides on the nuclear genome as shown in Figure 7A and B. The phylogenetic tree containing CsFRLS1 potentially encoded by CsFRLS1 and its counterparts from related viruses shows that CsFRLS1 is closely related to the genus Citrivirus within the family Betaflexiviridae (Figure 7C). The distance between CsFRLS1 and citriviruses are similar to intra-genus distances in the genera Carla-, Fovea-, Viti- and Potexviruses.

Discussion

The finding that the CP of a novel partitivirus, RnPV2 from a fungal phytopathogen matched a plant gene product, ILR2 from Ar. thaliana initiated a comprehensive search of the plant genomic sequence data available as of December 10, 2010 for non-retroviral RNA virus sequences (NRVSs) in plant genomes. While this study showed a variety of sequences related to the N (CP) genes of negative-stranded RNA viruses (cytorhabdoviruses and varicosaviruses) in members in the plant families including Solanaceae, Leguminosae, Brassicaceae and Phrymaceae, only one plus-sense RNA virus-related sequence (betaflexivirus replication-related gene) was found to be present in the cucumber genome. Furthermore, this survey detected sequences related to CP from dsRNA viruses (partitiviruses) (PCLSs) in various plants in addition to PCLSs reported by Liu et al. [24]. These authors performed a thorough search of eukaryotic genomic sequences available as of September 2009 for NRVSs and showed multiple dsRNA virus-related sequences not only in plants but also animals. Importantly, many of the NRVSs revealed by BLAST searches in this study were subsequently identified in plant genomes by Southern blotting, genomic PCR and sequence analyses (Figures 1– 3, 5, 7, S1, S3). These findings provide interesting insights into plant nuclear genome evolution, plant phylogeny and virus/host interactions.

Horizontal gene transfer, HGT, can occur “from virus to plant” or “from plant to virus.” A retention profile of PCLS1 among plants strongly suggests that HGT may have involved the former direction. The family Brassicaceae of the order Brassicales includes the genus Arabidopsis, which is believed to have diverged after the split of the families Phrymaceae and Solanaceae, accommodates the genera Mimulus and Solanum and belong to different orders, Lamiales and Solanales, respectively (Figure 8). No PCLS1 homologs are found in Vitis vinifera or Carica papaya, and that this gene resides on non-orthologous chromosomal positions of Mim. guttatus (data not shown) and Arabidopsis-related species (Figure 1A). This strongly suggests that independent HGT events from virus to the Arabidopsis and Mim. guttatus lineages may have occurred (Figure 8). This observation is also true for other PCLSs. The families Solanaceae and Brassicaceae contain PCLS5s, while their counterparts are not found in other plants whose complete genome sequences are available (Figure 8). The observation that a relatively widely conserved gene PUX_4 is disrupted in Sol. phureja by SpPCLS5 (Figure 3A) provides additional evidence for its insertion into the PUX_4 locus. The HGT direction “from virus to plant” was further confirmed by phylogenetic analysis showing that plant PCLSs and partitivirus CPs are placed in a mixed way (Figure 4). Viral sequences are basal in each of the three major clades, supporting the direction of transfers from virus to plant.

Figure 8. Horizontal gene transfer of genome sequences of non-retroviral RNA viruses into plant genomes.

The cladogram was created based on previous reports by The Angiosperm Phylogeny Group (31) [69], Oyama et al. [43], Udvard et al. [70] and Phytozome (http://www.phytozome.net/). Plants whose integrated non-retroviral RNA virus sequences (NRVSs) were analyzed molecularly in this study are shown in red. Integrations of non-retroviral RNA virus sequences, PCLSs, RNLSs, and FRLS are shown next to the plant species retaining them. Presumed integration times of NRSVs are indicated by dots on the nodes. Numbers within the genome-integrated NRVSs refer to subgroups (possible different virus origins) of PCLS (yellow column), RNLS (blue column) and FRLS (pink column) (Tables 1, 2, S4, S5). Numbers are placed within or beneath the symbolized morphologies of viruses that are thought to be the source of integrations (spherical for partitivirus, PCLS; bacilliformed for rhabdovirus, RNLS; flexuous for betaflexivirus, FRLS).

The divergence time of plant lineages is estimated through a classical approach using fossils and mutations rates of some particular genes. Alternatively, if we assume that cellular genes evolve at a constant rate, their divergence time can be calculated from the genome-wide, spontaneous mutation rate determined on a generation basis in the laboratory [40]. Together with the patterns of occurrence of the non-retroviral integrated RNA virus sequences, these values allow us to estimate time of some, if not all, HGTs identified in this study. For example, the integration of PCLS1 (ILR2) may have post-dated the split of the lineages containing the genera Arabidopsis and Brassica (16.0–24.1 million years ago) and pre-dated the speciation of Arabidopsis spp., or more accurately the divergence of Arabidopsis and its closely related genera (Figure 8) (10–14 million years ago) [40], [41], [42]. The phylogenetic relation among PCLS1s from Arabidopsis and its close relatives within the tribe Camelina (Capsella, Olimarabidopsis, and Turritis) agrees with the phylogeny of the family Brassicaceae deduced from systematic analyses [43]. Moreover, assuming that the Ar. thaliana and Ar. arenosa separated 10 million years ago, the mutation rates calculated for PCLS1s between the 2 plants are estimated to be 6.8×10−9 base substitutions per site per year, a value close to the genome-wide base substitution rate, 7×10−9, reported for Ar. thaliana by Ossowski et al. [40]. These observations suggest that endogenized PCLS1s accumulated mutations in a manner similar to those of other nuclear sequences during the course of evolution after a single HGT event in an ancestral Arabidopsis plant.

The genome of B. rapa in the family Brassicaceae retained 2 PCLSs (BrPCLS4 and BrPCLS5) with low-level similarities to RnPV2 CP on chromosomal positions different from each other and from that of the PCLS1 (ILR2) homologs of Arabidopsis-related genera. No PCLS1 homolog was identified on the orthologous positions of the B. rapa genome, and no BrPCLS4 or BrPCLS5 homologs were found on the corresponding locus of the Ar. thaliana or Ar. lyrata genome. Therefore, BrPCLS4 and 5 may have been introduced into the B. rapa genome separately from each other and from PCLS1 (ILR2) after the divergence of the Brassica and Arabidopsis lineages (Figure 8). Similarly, the detection profile of AtPCLS2 and AlPCLS3 (Figure 2) shows that they may have been introduced into Ar. thaliana and Ar. lyrata chromosomes independently after the separation of 2 plant species (3.0–5.8 million years ago) (Figure 8); these are more recent HGT events than the PCLS1 integration into the Arabidopsis lineage. PCLS integrations into the Solanaceae lineage were slightly complex. Relatively high or moderate levels of aa sequence identities (47–68%) are shared within the PCLS5s from the family Solanaceae. However, a lack of information regarding genome sequences flanking the PCLS5s caused difficulty in determining whether a single event or multiple HGT events may have occurred within the lineage (Figure 8).

Gene sequences related to rhabdovirus or varicosavirus N (CP) genes (RNLSs) are detected in many genera including Brassica, Raphanus, Mimulus, Nicotiana, Lotus, Malus, Cucumis, Populus, Theobroma, and Aquilegia (Figures 5, 8, S3). Using similar rationale for the HGT of PCLSs, multiple integrations of RNLSs into plant chromosomes are thought to have occurred (Figure 8). RNLSs are distributed in an irregular manner in the plant lineage, while rhabdovirus N proteins show similar tree topology to that exhibited by corresponding RdRps. This is consistent with the hypothesis that HGT occurred “from virus to plants.” RNLS2 was detected in a very narrow range of plants, i.e., detectable only in N. tabacum but not other Nicotiana species (Figure 5). RNLS1 was detected in all tested Brassica species, R. sativus and Aq. coerulea, while it was not detected in the genomes of Ar. thaliana [25] or Ar. lyrata (Phytozome), which are much closely related to Brassica than Aq. coerulea to Brassica. If these sequences were of plant origin, homologous sequences are expected to be retained at least within some members of the families Brassicaceae and Solanaceae. However, Southern blotting and genomic PCR analyses with NtRNLS2- and BrRNLS1-specific probes and primers failed to detect their related sequences in plants other than N. tabacum, and Brassica species and R. sativus, respectively (Figure 5C–F). A search using NtRNLS2 and BrRNL1 against the genome sequences of Ar. thaliana and Ar. lyrata did not yield any hits. This indicates that multiple HGTs of RNLSs occurred from “virus to plant.” While the BrRNLS1 integration may have postdated the split of the Arabidopsis and Brassica lineages (43.2–18.5 million years ago), NtRNLS2 and NtRNLS3 integration may have occurred after the divergence of N. tabacum (allotetraploid) and its maternal parent N. sylvestris (diploid) (0.2 million years ago) [44]. This hypothesis must be verified by sequence analysis of the corresponding regions of N. tabacum and other Nicotiana species.

The detection pattern of PCLSs within the family Brassicaceae provided an interesting insight into the phylogenetic relationship of some genera in the family. The family Brassicaceae is one of the largest families comprising over 300 genera and approximately 3,300 species that include an important plant biology model plant, Ar. thaliana, and agriculturally important Brassica species. Their phylogenetic relationships have been extensively studied and are occasionally controversial, because they rely on data sets and methods exploited for analyses. For example, placement of the genus Crucihimalaya is interesting to note in relation to this study. The genus is placed into a clade containing the genus Boechera, and is assumed to have separated from an ancestor common to the genus Capsella after the divergence of the Arabidopsis lineage based on phylogenetic analyses with a single nuclear gene (chalcone synthase gene) [45] or multiple data sets containing plastid and nuclear genes [45], [46], [47], [48]. However, utilization of different data sets shows different tree topologies, suggesting that the Crucihimalaya genus may have diverged before the split between Arabidopsis and Capsella [45], [49]. PCLS1s (ILR2 homologs) were detected in relatives of Arabidopsis but not in Cru. lasiocarpa (Figure 1B, D), strongly supporting the phylogenetic relation proposed by Lysak et al. [49]. The absence of the PCLS1 in a homologous position of the Cru. lasiocarpa chromosome was confirmed by sequencing of genomic PCR fragments generated with a specific primer set (Figure 1D). Therefore, these results clearly indicate that PCLSs have the potential to supplement phylogenetic estimates by serving as molecular markers. Furthermore, a similar insight into phylogenetic relations among Nicotiana species may be gained from data regarding 4 PCLSs identified in N. tabacum as more data in the genome and PCLS sequences of the genus Nicotiana become available.

Many examples of HGT from minus-sense RNA and dsRNA viruses, particularly from partitiviruses, have been found in plant nuclear genomes. Endogenization of NRVSs required 3 events to occur: (1) replication of the ancestral viral genome in the germ lines of host plants, (2) reverse transcription of genomic RNA, and (3) its subsequent integration into plant chromosomes. Many plant viruses are reported to be transmitted through pollens and seeds [50], while their transmission rates depended on virus/host combinations. Seed-transmitted viruses include positive-strand and negative-strand RNA viruses and partitiviruses with dsRNA genomes. The family Partitiviridae accommodates members that infect plants or fungi, and some plant and fungal partitiviruses are phylogenetically closely related ([21]; Figure 4). PCLS1 is most closely related to a novel fungal partitivirus, RnPV2, but the other PCLSs show the closest resemblance to plant partitiviruses (Table 1, Figure 4). Therefore, PCLS1 integration occurred when an ancestor of RnPV2 acquired the ability to infect an ancestral plant during endosymbiotic [51] or parasitic interactions between its host fungus and the plant, a host of the fungus, and to invade the plant germ cells. In support of this hypothesis, an assembled EST sequence is present in F. pratensis that is more closely related to PCLS1 than the RnPV2 CP gene and considered to have originated in a plant partitivirus (Figure 4). Such a virus may have been a direct source of plant PCLS1. Alternatively some fungal partitiviruses may be intrinsically able to infect plant cells. The expected capability of plant partitiviruses to replicate in host germ cells may be associated with their high rates (∼100%) of seed transmission via ovule and/or pollen [21], an uncommon phenomenon for plant viruses. Although germ lines are hypothesized to have the ability to eliminate virus infection, partitivirus may be able to overcome such a host mechanism. It is also likely that ancestral negative-strand RNA viruses may have invaded germ cells of host plants.

For the second required event, integration of NRVSs likely involved reverse transcription that may have been mediated by reverse transcriptase encoded by retrotransposons or pararetroviruses. However, the mechanism by which the viral RNA sequences were converted to DNA and introduced into plant genomes remains unknown. Interestingly LjPCLS8 harbors an unrelated sequence of 1.3-kb sequence in its central region (Figure S1A, D), suggesting a recombination event of during reverse transcription or a 2-step integration of 2 distinct molecules, PCLS8 and a sequence of an unknown origin. For the third event, as suggested by Liu et al. [24], transposon-mediated integration [52] and/or double-strand-break repair (non-homologous recombination) [53] may be involved. Flanking regions of some plant genome-integrated NRVSs (e.g., RNLS1s and CsFRLS1, see Figures 7, S3) carried transposable elements or multiple repeat sequences, supporting the first type of integration. Vertebrate cultured cells are useful for experimentally monitoring de novo integrations of negative-strand RNA viral sequences [11]; however, the agents that facilitate the reverse transcription and integration steps remain unknown.

In contrast to the nuclear integrations of partitivirus CP sequences and negative-strand RNA virus N sequences, plus-strand RNA virus endogenizations were observed much less frequently. A level of viral transcripts in germ cells may be one of factors governing the frequency of NRVSs. This is supported by the observation (data not shown) that, whereas we searched for integrated partitiviral RdRp sequences or other non-N sequences of rhabdoviruses, we could seldom detect them. Partitivirus CP and rhabdovirus N coding transcripts are highly likely to be produced in cells infected by the respective viruses more than other viral transcripts. Plus-strand RNA viruses, are believed to accumulate in infected plant cells much more than plant partitiviruses. However, plus-strand RNA viruses may generally be more able to be detected by a surveillance system of host germ cells and/or less competent to escape from their defense system. A smaller number of FRLS integrations observed in this study (Figure 7) may be associated with a lower ability of ancestral plus-strand RNA viruses to invade host germ cells, as predicted from the low seed transmissibility of CLBV [54]. Alternatively, plus-strand RNA virus sequences are disfavored by reverse transcriptase and agents that facilitate integration of their complementary DNA in the second and third events, respectively, although this possibility may be low.

Materials and Methods

Fungal strains and virus characterization

A virus-infected fungal strain of R. necatrix, W57, was isolated in the Iwate Prefecture, Japan. Molecular characterization of genomic dsRNAs were performed according to the methods described by Chiba et al. [55], unless otherwise mentioned.

Plant materials and gene characterization

Seeds for members of the Brassicaceae family, L. japonicus, Med. truncatula and Cuc. sativus cv. Borszczagowski B10 line were provided by the Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center of The Ohio State University, the Frontier Science Research Center, University of Miyazaki, and Drs. Kazuhiro Toyoda, Douglas Cook, and Grzegorz Bartoszewski, respectively. Seeds for members of the genus Nicotiana were originally obtained from Nihon Tabako, Inc (Tokyo, Japan) and maintained at Okayama University. Dr. Takashi Enomoto of Okayama University provided the remaining plants. Plant genomic DNA was isolated from seeds or fresh leaf materials and used in genomic PCR and Southern blot analyses as described by Miura et al. [56]. Sequences of ILR2 homologs (PCLS1s) from members of the family Brassicaceae, except for Ar. thaliana accessions Col-0 and WS, and Ar. lyrata, were obtained by sequencing genomic PCR fragments. Genomic PCR fragments or clones were used to determine the sequences of other selected PCLSs, RNLSs and FRLSs. Digoxigenin (DIG)-labeled DNA, prepared as described by Chiba et al. [55], was used as probes in Southern blotting analyses as described by Faruk et al. [57]. Table S3 includes sequences of primers used in this study.

Database search and phylogenetic analysis

BLAST (tblastn) searches [58] were conducted against genome sequence databases available from the NCBI (nucleotide collection, nr/nt; genome survey sequences, GSS; high-throughput genomic sequence, HTGS; whole-genome shotgun reads, WGS; non-human, non-mouse ESTs, est others) (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/), Phytozome v6.0 (http://www.phytozome.net/), Brassica database (BRAD) (http://brassicadb.org/brad/), Potato Genome Sequencing Consortium (http://potatogenomics.plantbiology.msu.edu/), and Kazusa DNA Research Institute (http://www.kazusa.or.jp/e/index.html). The databanks covered the complete and partial genome sequences of 20 plant species. Transposable element sequences were identified using the Censor (http://www.girinst.org/censor/index.php) [59]. Obtained non-retroviral integrated sequences were translated to amino acid sequences and aligned with MAFFT version 6 under the default parameters [60] (http://mafft.cbrc.jp/alignment/server). For some non-retroviral integrated sequences with interrupted ORFs, frames were restored by adding Ns as unknown sequences to obtain continuous aa sequences (edited residues are shown as Xs). Alignments were edited by using MEGA version 4.02 software [61]. To obtain appropriate substitution models for the maximum likelihood (ML) analyses, each data set was subjected to the Akaike information criterion (AIC) calculated using ProtTest server [62] (http://darwin.uvigo.es/software/prottest_server.html). According to ProtTest results, WAG+I+G+F, LG+I+G, and LG+I+G+F were selected for PCLSs and partitiviruses, for RNLSs, plant rhabdoviruses and varicosaviruses, and for FRLS and flexiviruses, respectively. Phylogenetic trees were generated using the appropriate substitution model in PhyML 3.0 [63] (http://www.atgc-montpellier.fr/phyml/). In each analysis, four categories of rate variation were used. The starting tree was a BIONJ tree and the type of tree improvement was subtree pruning and regrafting (SPR) [64]. Branch support was calculated using the approximate likelihood ratio test (aLRT) with a Shimodaira–Hasegawa–like (SH-like) procedure [65]. The tree was midpoint-rooted using FigTree version 1.3.1 software (http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/).

Data deposition

Two mycoviral genome sequences and a total of 73 non-retroviral integrated RNA virus sequences were analyzed. Sequence data (1 of the 2 genome segments of RnPV2, 21 PCLSs, 12 RNLSs and 1 FRLS) used for phylogenetic analyses in this article have been deposited into the EMBL/GenBank/DDBJ Data Library under the following accession numbers: AB569998 (RnPV2 dsRNA2), AB576168–AB576175, AB609326–AB609329 (ILR2-like sequences: PCLS1s), AB609330–AB609338 (PCLS2–PCLS8), AB9339–AB609350 (RNLSs), and AB610884 (CsFRLS1) (Tables S4 and S5). Other non-retroviral integrated RNA virus elements whose sequences were partially determined and analyzed in this study are available upon request.

Supporting Information

Detection of PCLS s from members of the genus Nicotiana , and Med. truncatula and L. japonicus . (A) Schematic representation of genome organization of partitivirus genome segments and PCLSs from N. tabacum, Med. truncatula and L. japonicus. RSCV1 dsRNA2 encodes CP of 505 amino acids that is closely related to PCLS5s, including NtPCLS5-1 and NtPCLS55-2. NtPCLS5-1 and NtPCLS5-2 share 47% sequence identity. NtPCLS6 and NtPCLS7 show the highest levels of similarity to the C-terminal and central portions of CPs encoded by FCCV dsRNA3 and RSCV3 dsRNA2, respectively. These NtPCLSs were detected in contigs independently assembled with sequences in the NCBI GSS database [24]. See the Figure 1 legend for explanation of the symbols. (B–D) Genomic PCR analyses of PCLS 5 to PCLS8. PCR was carried out on DNA templates from Nicotiana plants (B), three lines of Med. truncatula (C), and 2 lines of L. japonicus and G. max (D), as shown on the top of the panel. Primer sets specific for NtPCLS5-1 (PC5-1-1 and PC5-1-2), NtPCLS5-2 (PC5-2-1 and PC5-2-2), NtPCLS6 (PC6-1 and PC6-2), NtPCLS7 (PC7a-1 and PC7a-2), MtPCLS7 (PC7b-1 and PC7b-2), LjPCLS8 (PC8-1 and PC8-2), and the ITS region (ITS-F and ITS-R) were used for PCR and indicated at the right of the panels. Primer positions are shown in A. (E) Southern blotting of PCLS5 to PCLS7. EcoRI-digested genomic DNA was used for detection using DIG-labeled DNA probes specific for NtPCLS5-1, NtPCLS5-2, NtPCLS6, NtPCLS7 and NbPCLS7, and N. tabacum ITS. Four plant species, B. rapa, Sol. tuberosum, N tabacum, and N. benthamiana were analyzed. NtPCLS5-2 possesses an internal EcoRI recognition site. No cross-hybridization was observed on Southern blots under the conditions used in this study between NtPCLS7 and NbPCLS7, which share 75% nucleotide sequence identity with 6 gaps between the sequences (compare sizes of PCR fragments in lane N. tabacum and the other lanes of the fourth panel of Figure S1B).

(TIF)

Alignment of plant partitivirus CPs and their related plant sequences (PCLSs). The entire region of RnPV2 CP (aa 1–483) was aligned with homologous sequences from other plant and fungal partitiviruses, translated EST sequences of possible plant partitivirus origin, and plant PCLSs using the program MAFFT version 6. The alignment was used to generate a phylogenetic tree, as shown in Figure 4. For full virus names and information on PCLSs, see the Figure 4 legend, and Tables 1 and S4. Three relatively well conserved sequences, PGPLxxxF, F/WxGSxxL and GpfW domains are marked in red.

(PDF)

Schematic representation of chromosomal positions of RNLS s and their detection by genomic PCR. (A) Map positions of a total of 11 RNLSs are depicted. Their source plants, such as cucumber, apple, and N. tabacum are shown at the left. RNLS1s showed highest levels sequence similarities to the CP of LBVaV, while the other RNLSs are most closely related to the N protein of cytorhabdovirus, either lettuce necrotic yellows virus (LNYV), northern cereal mosaic virus (NCMV) or lettuce yellow mottle virus (LYMoV). Contigs were constructed from GSSs of N. tabacum as shown below the chromosomal positions of NtRNLS2 and NtRNLS3. Sequences related to transposable elements or repeat sequences are shown by black thick lines. See the legend to Figure 1 for explanation of the other symbols. (B–H) Molecular detection of RNLSs from several plants. Representative RNLSs from Aq. flabellata (B), Mal. domestica (C, D), L. japonicus (E, F), Cuc. sativus (G), and N. tabacum (H) were detected by genomic PCR and sequencing. Primers' positions and sequences are shown in A (arrows) and Table S3. Entire regions of RNLSs were amplified in all PCR assays (A to F), while in panels B and E partial forms of RNLSs were also amplified. Most sequences of DNA fragments were identical to those available from the respective genome sequence databases.

(TIF)

RNLS Contigs constructed from EST libraries of different plants. Rhabdovirus nucleocapsid (N)-like sequences were detected by searching EST databases for F. pratensis, Aq. formosa×Aq. pubescens, B. oleracea, B. napus, Cic. intybus, Picea glauca, and Triphysaria pusilla. Multiple ESTs were used to construct contigs where overlapping regions of EST sequences show over 99% sequence identity. These ESTs are either from endogenized viral sequences or infecting viruses.

(TIF)

Alignment of plant rhabdovirus and varicosavirus N proteins and plant nuclear encoded RNLSs. The entire nucleocapsid protein (N) sequences (approximately 450 aa) of plant rhabdoviruses and varicosaviruses (approximately 450 aa) and plant rhabdovirus N-like proteins (RNLSs) were aligned using the program MAFFT version 6. The alignment was used to generate a phylogenetic tree, as shown in Figure 6. For non-abbreviated virus names and information on RNLSs, see the Figure 6 legend, and Tables 2 and S5. Two conserved motifs GmH and YaRifdxxxfxxLQtkxC are marked in red.

(PDF)

Alignment of a plant nuclear encoded FRLS and betaflexivirus replicase proteins. The partial replicase polyprotein sequences (approximately 1500 aa) from Cuc. sativus (cucumber) (CsFRLS1), all Betaflexiviridae genera (Citri-, Carla-, Fovea-, Viti-, Capillo-, and Trichoviruses) and a member of the family Alphaflexivirdae (potato virus X) were aligned using the program MAFFT version 6. The alignment was used to generate a phylogenetic tree, as shown in Figure 7C. Conserved methyltransferase, RNA helicase (partial), and RdRp motifs are marked in red.

(PDF)

Virus gene sequences used as query sequences in the search for non-retroviral integrated RNA viruses.

(DOC)

Amino acid sequence identities among selected partitivirus CPs and plant Partitivirus CP-like sequences (PCLSs).

(DOC)

Oligonucleotide primers used in this study.

(DOC)

Partitivirus CP-like sequences (PCLSs) analyzed in this study.

(DOC)

Rhabdovirus N-like sequences (RNLSs) analyzed in this study.

(DOC)

Rhabdovirus N-like sequences (RNLSs) identified in plant EST collections.

(DOC)

Amino acid sequence identities among selected rhabdovirus Ns/CPs and plant rhabdovirus N-like sequences (RNLSs).

(DOC)

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Dr. Yukio Shirako for fruitful discussion, and to Drs. Takashi Enomoto, Kazuhiro Toyoda, Douglas Cook, Sanwen Huang, Yongchen Du, Grzegorz Bartoszewski, the National BioResource Project Office, Frontier Science Research Center, University of Miyazaki, and the Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center, Ohio State University for seeds of cucumber, Med. truncatula, L. japonicus and relatives of Ar. thaliana. The authors also thank Kazuyuki Maruyama for technical support.

Footnotes

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

The work is supported by Yomogi Inc. (to NS), a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research [KAKENHI 21580056] from the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sport, Science and Technology (to HK and NS), and the Program for Promotion of Basic and Applied Researches for Innovations in Bio-Oriented Industries (PROBRAIN) (to HK and SK). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Gorbalenya AE. Host-related sequences in RNA viral genomes. Semin Virol. 1992;3:359–371. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meyers G, Rumenapf T, Thiel HJ. Ubiquitin in a togavirus. Nature. 1989;341:491. doi: 10.1038/341491a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mayo MA, Jolly CA. The 5′-terminal sequence of potato leafroll virus RNA: evidence of recombination between virus and host RNA. J Gen Virol. 1991;72:2591–2595. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-72-10-2591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Agranovsky AA, Boyko VP, Karasev AV, Koonin EV, Dolja VV. Putative 65 kDa protein of beet yellows closterovirus is a homologue of HSP70 heat shock proteins. J Mol Biol. 1991;217:603–610. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(91)90517-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dolja VV, Kreuze JF, Valkonen JP. Comparative and functional genomics of closteroviruses. Virus Res. 2006;117:38–51. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2006.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bertsch C, Beuve M, Dolja VV, Wirth M, Pelsy F, et al. Retention of the virus-derived sequences in the nuclear genome of grapevine as a potential pathway to virus resistance. Biol Direct. 2009;4:21. doi: 10.1186/1745-6150-4-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gayral P, Noa-Carrazana JC, Lescot M, Lheureux F, Lockhart BE, et al. A single Banana streak virus integration event in the banana genome as the origin of infectious endogenous pararetrovirus. J Virol. 2008;82:6697–6710. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00212-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Richert-Poggeler KR, Noreen F, Schwarzacher T, Harper G, Hohn T. Induction of infectious petunia vein clearing (pararetro) virus from endogenous provirus in petunia. EMBO J. 2003;22:4836–4845. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kunii M, Kanda M, Nagano H, Uyeda I, Kishima Y, et al. Reconstruction of putative DNA virus from endogenous rice tungro bacilliform virus-like sequences in the rice genome: implications for integration and evolution. BMC Genomics. 2004;5:80. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-5-80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Geuking MB, Weber J, Dewannieux M, Gorelik E, Heidmann T, et al. Recombination of retrotransposon and exogenous RNA virus results in nonretroviral cDNA integration. Science. 2009;323:393–396. doi: 10.1126/science.1167375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Horie M, Honda T, Suzuki Y, Kobayashi Y, Daito T, et al. Endogenous non-retroviral RNA virus elements in mammalian genomes. Nature. 2010;463:84–87. doi: 10.1038/nature08695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Belyi VA, Levine AJ, Skalka AM. Unexpected inheritance: multiple integrations of ancient bornavirus and ebolavirus/marburgvirus sequences in vertebrate genomes. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1001030. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Katzourakis A, Gifford RJ. Endogenous viral elements in animal genomes. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1001191. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Taylor DJ, Leach RW, Bruenn J. Filoviruses are ancient and integrated into mammalian genomes. BMC Evol Biol. 2010;10:193. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-10-193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koonin EV. Taming of the shrewd: novel eukaryotic genes from RNA viruses. BMC Biol. 2010;8:2. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-8-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Taylor DJ, Bruenn J. The evolution of novel fungal genes from non-retroviral RNA viruses. BMC Biol. 2009;7:88. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-7-88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Frank AC, Wolfe KH. Evolutionary capture of viral and plasmid DNA by yeast nuclear chromosomes. Eukaryot Cell. 2009;8:1521–1531. doi: 10.1128/EC.00110-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arakawa M, Nakamura H, Uetake Y, Matsumoto N. Presence and distribution of double-stranded RNA elements in the white root rot fungus Rosellinia necatrix. Mycoscience. 2002;43:21–26. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ikeda K, Nakamura H, Arakawa M, Matsumoto N. Diversity and vertical transmission of double-stranded RNA elements in root rot pathogens of trees, Helicobasidium mompa and Rosellinia necatrix. Mycol Res. 2004;108:626–634. doi: 10.1017/s0953756204000061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ghabrial SA, Suzuki N. Viruses of plant pathogenic fungi. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 2009;47:353–384. doi: 10.1146/annurev-phyto-080508-081932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ghabrial SA, Ochoa WF, Baker T, Niber ML. Partitiviruses: general features. In: Mahy BWJVRM, editor. Encyclopedia of Virology 3rd edn. Oxford: Elsevier; 2008. pp. 68–75. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koonin EV, Wolf YI, Nagasaki K, Dolja VV. The Big Bang of picorna-like virus evolution antedates the radiation of eukaryotic supergroups. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2008;6:925–939. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Magidin M, Pittman JK, Hirschi KD, Bartel B. ILR2, a novel gene regulating IAA conjugate sensitivity and metal transport in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 2003;35:523–534. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2003.01826.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu H, Fu Y, Jiang D, Li G, Xie J, et al. Widespread horizontal gene transfer from double-stranded RNA viruses to eukaryotic nuclear genomes. J Virol. 2010;84:11876–11887. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00955-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Initiative TAG. Analysis of the genome of the flowering plant Arabidopsis thaliana. Nature. 2000;408:796–815. doi: 10.1038/35048692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Renna L, Hanton SL, Stefano G, Bortolotti L, Misra V, et al. Identification and characterization of AtCASP, a plant transmembrane Golgi matrix protein. Plant Mol Biol. 2005;58:109–122. doi: 10.1007/s11103-005-4618-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]