Abstract

Mice with thyroid-specific expression of oncogenic BRAF (Tg-Braf) develop papillary thyroid cancers (PTC) that are locally invasive and have well-defined foci of poorly differentiated carcinoma (PDTC). To investigate the PTC-PDTC progression, we performed a microarray analysis using RNA from paired samples of PDTC and PTC collected from the same animals by laser capture microdissection. Analysis of 8 paired samples revealed a profound deregulation of genes involved in cell adhesion and intracellular junctions, with changes consistent with an epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT). This was confirmed by IHC, as vimentin expression was increased and E-cadherin lost in PDTC compared to adjacent PTC. Moreover, PDTC stained positively for phospho-Smad2, suggesting a role for TGFβ in mediating this process. Accordingly, TGFβ induced EMT in primary cultures of thyroid cells from Tg-Braf mice, whereas wild-type thyroid cells retained their epithelial features. TGFβ-induced Smad2 phosphorylation, transcriptional activity and induction of EMT required MAPK pathway activation in Tg-Braf thyrocytes. Hence, tumor initiation by oncogenic BRAF renders thyroid cells susceptible to TGFβ-induced EMT, through a MAPK-dependent process.

INTRODUCTION

The BRAFT1799A mutation, which encodes BRAFV600E, is the most common genetic event in papillary thyroid cancers (PTC) (Kimura et al. 2003; Xing 2005; Soares et al. 2003). PTCs with BRAF mutations have a higher prevalence of extrathyroidal invasion, lymph node metastases, and have a higher rate of recurrence and decreased survival (Elisei et al. 2008; Soares et al. 2003). BRAFV600E mutation has also been demonstrated to predict a worse outcome in poorly differentiated thyroid cancers (PDTC) (Ricarte-Filho et al. 2009).

The evidence supporting a stepwise progression from PTC to PDTC is based primarily on the observation that distinct regions of PTC and PDTC (or ATC) frequently coexist within the same tumor (Ricarte-Filho et al. 2009; Nikiforova et al. 2003; Namba et al. 2003). The histopathological definition of human PDTC is controversial, which has confounded the interpretation of genetic and gene expression studies of this clinical entity. Mutations of P53 and CTNNB1 are found in anaplastic thyroid cancers (Fagin et al. 1993), and in a small proportion of PDTC. PDTC with BRAF mutations are also associated with mutations of PIK3CA or AKT1, primarily in metastases with high metabolic activity (Ricarte-Filho et al. 2009). Most studies of PDTC compared small numbers of PTC and PDTC samples from different patients, and thus had a limited resolution to identify events leading to phenotypic progression.

Tg-Braf mice overexpress BRAFV600E in thyroid cells, under the regulatory control of the thyroglobulin (Tg) gene promoter (Knauf et al. 2005). These mice develop invasive PTCs with high penetrance and short latency, which progress to PDTCs later in life, providing a model to explore mechanisms of disease progression. To this end, we analyzed expression profiles of paired PTC/PDTC foci to identify possible triggering events responsible for the PTC to PDTC transition. Our data point to an important role for TGFβ in this process, through induction of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT). Oncogenic BRAF induces TGFβ1 secretion in vitro, and a TGFβ-driven autocrine loop may mediate in part the effects of the oncoprotein on the activity of the sodium iodide transporter (NIS), as well as on cell migration, invasiveness and EMT (Riesco-Eizaguirre et al. 2009). The studies reported here indicate thyroid cancer cells that develop in vivo following BRAF activation are susceptible to undergo EMT in response to TGFβ, and that this requires concomitant constitutive activation of MAPK, and that these two pathways converge on Smads to modulate TGFβ transcriptional output.

RESULTS

Gene expression profiles of PTC and PDTC from Tg-Braf mice

Tg-Braf mice develop PTC by 3 weeks of age, and by 5 months virtually all cancers are locally invasive. At this time approximately 50% have distinct focal areas of PDTC (Knauf et al. 2005), which are characterized by spindle-shaped cells with a solid pattern of growth and increased number of mitotic figures (Fig 1A). To identify gene expression changes involved in the transition from PTC to PDTC, we used laser capture microdissection (LCM) to isolate cells from individual poorly differentiated foci and a corresponding area of PTC from 8 Tg-Braf mice (Fig 1B). RNA was isolated from the laser captured cells of PTC and PDTC paired samples, amplified, labeled with Cy5 or Cy3, and co-hybridized to the microarray chips. This identified 1630 genes with significant expression changes (p<0.05, FDR<0.1). Of these, 955 gene products decreased and 675 increased in the PDTC compared to the PTC. To identify signaling pathways that may mediate or contribute to these expression changes we used LRPath (Sartor et al. 2009) to compare our data set to the following databases: Gene Ontology, MeSH, Metabolite, KEGG pathways, Biocarta pathways, Pfam, Panther pathways, OMIM, Cytoband and DrugBank, as defined in the functional enrichment program ConceptGen (Sartor et al. 2010). Representative concept categories that were found to be significantly represented (p<0.001 and FDR<0.01) are listed in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2.

Figure 1. LCM of PDTC and PTC in Tg-Braf mice.

A) (a) H&E staining of a thyroid from a Tg-Braf mouse replaced by PTC (black arrow) and containing foci of PDTC (white arrows)(100×). (b) Mitotic cell in a focus of PTDC (black arrow) (400×). B) Representative images of thyroid from Tg-Braf mice before and after laser capture of discrete regions of PTC and PDTC stained with HistoGene™ LCM Frozen Section Staining Kit (Arcturus, Mountain View, CA).

EMT occurs during progression of PTC to PDTC

The main concept categories altered in the PTC-PDTC transition included “extracellular matrix”, “cell adhesion”, “tight junctions” and “apicolateral plasma membrane”. Genes involved in tight junctions, desmosomes, and adherent junction proteins were significantly downregulated, whereas expression of intermediate filament and basement membrane genes was increased (Table 1). These expression changes indicate that an EMT occurred during progression from PTC to PDTC. To confirm this, a second set of 5 thyroids from Tg-Braf animals containing foci of PDTC were stained for E-cadherin and vimentin (Fig 2A). All foci of PDTC lacked E-cadherin staining, and stained strongly for vimentin, confirming the microarray results, and the mesenchymal phenotype of PDTC. By contrast, regions of PTC stained strongly for E-cadherin, and weakly or not at all for vimentin.

Figure 2. PDTC developing in Tg-Braf mice undergo EMT.

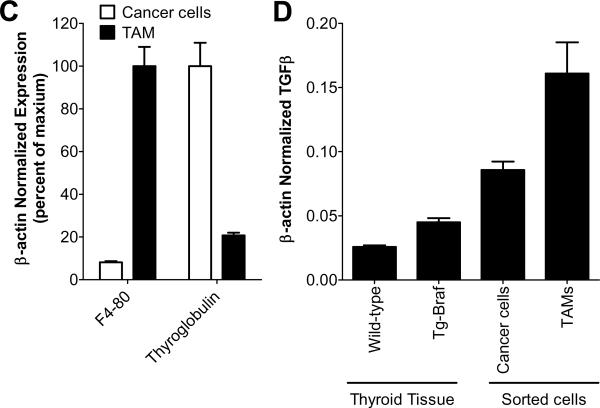

A) A representative thyroid from a Tg-Braf mouse entirely replaced with PTC and harboring multiple foci of PDTC (indicated by arrows) stained with H&E (i, ii), E-cadherin (iii,iv), vimentin (v,vi) or pSmad2 (vii,viii) at 40× (i,iii,v,vii) and the PDTC at 200× (ii,iv,vi,viii). Images in panels vii and viii were acquired using the Nuance imaging system which converted the hematoxyllin blue counter stain to red, and the brown pSmad stain to blue, to allow better distinction of pSmad from the counter stain. B) A representative PTC and PDTC from a Tg-Braf mice stained for the activated macrophage marker, MAC-2 (200×). C) Bars represent β-actin normalized mRNA levels of F4-80 and thyroglobulin in TAMs and thyroid cancer cells, respectively, isolated from LSL-BrafV600E/TPO-Cre/ROSA26-EGFPf/f thyroids using cell sorting. D) Bars represent β-actin normalized mRNA levels of TGFβI in wild-type thyroid tissue, Tg-Braf PTCs, isolated TAMs or isolated Braf-expressing thyroid cancer cells.

Marked increase in pSmad2 in PDTC

In other model systems induction of EMT involves activation of TGFβ signaling pathways (reviewed in (Xu et al. 2009)). Expression of BRAFV600E in the well-differentiated thyroid cell line PCCL3 was recently reported to increase secretion of TGFβ1 (Riesco-Eizaguirre et al. 2009). We found that TGFβ1 expression was increased 1.7-fold (p=0.002) in Tg-Braf thyroids compared to normal by RT-PCR (Fig 2D). A further increase in TGFβ signaling in PDTC compared to PTC was supported by ConceptGen analysis (Sartor et al. 2010), which found that 123 genes that were differentially regulated in the PDTC also had expression changes in immortalized ovarian surface epithelial cells treated with TGFβ (p=7.6×10−11). To provide an independent measure of TGFβ pathway activation in PDTC, we performed IHC for phospho (S465/467) Smad2, and found a marked increase in pSmad2 positive cells in PDTC compared to adjacent PTC (Fig 2A). Interestingly, tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), which are a known source of TGFβ (Savage et al. 2008), are present in high numbers in human PDTC and anaplastic thyroid cancers (Ryder et al. 2008). As shown in Fig 2B, TAM abundance was also markedly increased in regions of PDTC compared to PTC (Fig 2B). To further investigate the source of the TGFβ we isolated thyroid follicular cells and tumor associated macrophages (TAM) from BrafV600E-induced mouse thyroid papillary cancers, obtained from mice that express endogenous levels of the oncoprotein (please see Methods), and that phenocopy Tg-Braf mice in penetrance of PTC, and development of PDTC with aging. RNA extracted from cells isolated by FACS was first analyzed by qRT-PCR for expression of F4–80 and thyroglobulin, to confirm >80% enrichment of TAMs and thyrocytes, respectively (Fig 2C). qRT-PCR for TGFβ demonstrated that both TAMs and thyroid cancer cells express TGFβ, with slightly more expression in the TAMs (Fig 2D). The abundance of TGFβ is also regulated by proteolytic cleavage of its latent form, but this could not be resolved in this model.

TGFβ-induced EMT requires MEK activation in Tg-Braf thyrocytes

We next examined whether TGFβ was sufficient to induce EMT in primary cultures of Tg-Braf PTCs. Incubation with TGFβ induced a spindle-shape morphology in Tg-Braf thyroid cells (Fig 3A), but not wild-type thyroid cells (Fig 3B), which was associated with increased vimentin and loss of E-cadherin immunostaining. The vimentin (+) E-cadherin (−) cells were confirmed to be epithelial by staining for cytokeratin. Accordingly, vimentin and E-cadherin mRNA levels were regulated reciprocally by TGFβ (Fig 3C). Expression of the E-cadherin repressors Snail 1, Zeb1, and Zeb2 was increased, suggesting that these genes may help mediate induction of EMT by TGFβ in Tg-Braf thyroid cancer cells. By contrast, TGFβ did not evoke changes in vimentin and E-cadherin expression or localization in wild-type thyroid cells (Fig 3B). This suggests that constitutive MAPK activation may be required for TGFβ to induce EMT in cells transformed by oncogenic Braf. Consistent with this, addition of the MEK inhibitor U0126 blunted the TGFβ-induced EMT, as shown by the lack of effect on cell morphology and unchanged vimentin or E-cadherin localization (Fig 3A).

Figure 3. TGFβ-induced EMT in primary cultures of Tg-Braf thyroid cells requires MAPK.

A&B) Thyroid cells isolated from Tg-Braf (A) or wild-type (B) mice were plated into chamber slides coated with collagen and incubated for 48 h. Cells were then incubated in the absence or presence of TGFβ (10 ng/ml) with or without U0126 (25 μM) for 6 days, with a medium change every 2 days. Cells in the left panels of (A) and (B) were co-stained for E-cadherin (green) and cytokeratin (red). Cells in the right panel were stained for vimentin (green) and cytokeratin (red). Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). C) Tg-Braf thyroid primary cells were plated into CellBind plates and incubated for 48 h. Cells were then incubated in the absence or presence of TGFβ for 10 days in serum-free medium. RNA was isolated and used in quantitative RT-PCR reactions for the indicated transcripts.

TGFβ-induced Smad2 phosphorylation and transcriptional activity is MEK dependent

TGFβ has been shown to activate MAPK in a Smad-independent manner (Derynck and Zhang 2003; Lee et al. 2007). In turn, MAPK can modulate TGFβ-induced signaling through phosphorylation of the MH1 or linker regions of Smad2 or 3 (Wrighton et al. 2009). As shown in Fig 4A, treatment of primary cultures of Tg-Braf thyrocytes with TGFβ resulted in increased levels of phospho (S465/467) Smad2, C-terminal sites known to be phosphorylated following activation of the TGFβ receptor, and to be required for its transcriptional function. By contrast, phosphorylation of threonine 8 in the MH1 region of Smad2 was not regulated by TGFβ. Pretreatment with a MEK inhibitor for 3 hours decreased p(T8) Smad2, and blunted the TGFβ-induced increase in p(S465/467)Smad2. The inhibitory effects of U0126 on TGFβ-induced Smad2 (S465/467) phosphorylation were confirmed in the mBraf-p53 immortalized cell line created from a transgenic mouse with thyroid-specific expression of BrafV600E and loss of p53. Here pre-treatment with the MEK inhibitor blunted TGFβ-induced Smad phospho S465/467 in a time-dependent fashion (Fig 4B). Total Smad levels were higher in cancer cells than in wild type thyrocytes (Fig 4C). After 24h incubation with MEK inhibitor total Smad levels were significantly reduced. Although the effects of MEK inhibition of Smad phosphorylation precede the changes in total Smad protein, it is important to note that Smad stability is also a recognized mechanism to regulate the output of the TGFβ signaling pathway ((Lin et al. 2000; Seo et al. 2004), reviewed in (Inoue and Imamura 2008)). In our model, the lower levels of Smad2 protein after prolonged treatment with U0126 are likely due to posttranscriptional events, as Smad2 mRNA levels were not decreased (data not shown).

Figure 4. TGFβ-induced transcription in Tg-Braf thyroid cells is MEK dependent.

A) Tg-Braf thyroid cells were plated into primary culture in CellBind plates and incubated for 48 h. Cells were then incubated in the absence or presence of U0126 (25 μM) for 3 h. TGFβ (10 ng/ml) was then added for 1h. Protein lysates were prepared and subjected to Western blotting for the indicated proteins. B) Immortalized mBraf-p53 cells were incubated in the absence or presence of U0126 (25 μM) for 1–3 h. TGFβ (10 ng/ml) was then added for 1h. Protein lysates were prepared and subjected to Western blotting for the indicated proteins. C) Tg-Braf or wild-type thyroid cells were plated into primary culture in CellBind plates and incubated for 48 h. Cells were then incubated in the absence or presence of TGFβ (10 ng/ml) with or without U0126 (25 μM) for 24 h. Protein lysates were prepared and subjected to Western blotting for the indicated proteins. D&E) Primary thyroid cells from wild-type (D) or Tg-Braf (E) mice were plated into 24-well plates coated with collagen and incubated for 48 h. Cells were then co-transfected with 3TP-lux and CMV-renilla lucerifase. Sixteen hours after transfection the medium was changed to medium with or without TGFβ (10 ng/ml) and U0126 (25 μM) and incubated for 36 h. Firefly and renilla lucerifase activity were then determined. Bars represent fold-change from untreated cells in firefly lucerifase activity after normalizing for differences in renilla lucerifase activity, and subtracting background activity as determined in cells transfected with pGL3-basic.

In many cell contexts, ERK activation has been associated with inhibitory effects on TGFβ signaling. Our results, by contrast, suggest that constitutive activation of the MAPK pathway is required for optimal TGFβ signaling in mouse thyroid cancer cells induced by Braf. To confirm this, we determined the effects of MEK inhibition on the activity of the TGFβ-Smad transcriptional reporter 3TP-Lux. TGFβ induced far greater 3TP-Lux reporter activity in Tg-Braf (7-fold) compared to wild-type thyroid cells (2-fold) (Fig 4 D,E). MEK inhibition blocked TGFβ-induced 3TP Lux reporter activity in both Tg-Braf and wild-type thyroid primary cultures.

EMT in human PTC progression to undifferentiated thyroid cancers

To investigate if EMT also occurs in progression of human thyroid cancers we immunostained a panel of differentiated and undifferentiated thyroids carcinoma tissue microarrays for E-cadherin. Consistent with other reports we found that most of the undifferentiated thyroid carcinoma specimens (14/18, 78%) lost membranous E-cadherin. The 4 undifferentiated carcinomas with membranous staining were squamous cell carcinomas or had squamoid features, while all the anaplastic carcinomas showing mesenchymal differentiation were negative for E-cadherin (Fig 5). By contrast, almost all well-differentiated papillary thyroid carcinomas (32/33, 97%) maintained membranous staining for E-cadherin (Fig 5). The difference in staining for E-cadherin between differentiated and undifferentiated tumors was significant (p<0.0001). To further explore the association of oncogenic BRAF with EMT, we stained an additional 7 ATC known to harbor BRAF mutations: 4 with mesenchymal differentiation, 2 with squamoid features, and 1 with mixed squamoid and mesenchymal features. The BRAF V600E (+) ATC with mesenchymal differentiation did not stain for E-cadherin, whereas those with squamoid features had membrane staining for E-cadherin. This indicates that loss of E-cadherin (i.e. EMT) is tightly associated with mesenchymal differentiation. However, the presence of BRAFV600E does not appear to predict whether an ATC will have squamoid or mesenchymal features. We were not able to optimize phospho (S465/467) Smad2 IHC on human FFPE sections to determine whether the EMT in undifferentiated carcinomas was associated with increased TGFβ signaling. However, a comparison of expression arrays from human BRAFV600E (+) PTC and ATC identified 1943 genes that were differentially regulated in the ATC compared to PTC, which included increased expression of TGFβI and decreased expression of Smad6, a negative regulator of TGFβ signaling. The activation of the TGFβ signaling pathway is also supported by ConceptGen analysis, which found that 177 of the differentially expressed genes were also altered in immortalized ovarian surface epithelial cells treated with TGFβ (p=3.4×10−11). Other representative concept categories identified by LRPath analysis of genes differentially expressed between BRAFV600E(+) human PTC and ATC are listed in Supplementary Tables 1 and 3. Most were related to cell division, which is consistent with the high mitotic rate of ATC. Interestingly, a number of concept categories were common to both mouse and human thyroid tumor progression (Supplementary Table 4). These include the categories “Extracellular matrix”, “Tight Junctions” and “Apicolateral plasma membrane”, further supporting EMT as a key event in progression of BrafV600E-mutant PTC to undifferentiated cancers in mice and human

Figure 5. Loss of E-cadherin staining in human anaplastic thyroid cancers.

Representative E-cadherin staining of a human anaplastic thyroid cancer (ATC) with an adjacent region of PTC. PTC cells show strong membrane E-cadherin staining, which is entirely lost in the surrounding ATC cells. Open arrow indicate ATC and solid arrow indicates an area of PTC. Left: 100×, Right: 400×.

DISCUSSION

Here, we aimed to identify events associated with thyroid cancer progression in a mouse model of tumorigenesis induced by BrafV600E. The expression profile of PDTC showed an unequivocal signature of EMT as compared bona fide to paired samples of PTC. We believe that the PDTC arising in Tg-Braf mice represent a progression event. Thus, they are unlikely to have arisen de novo from a distinct thyroid progenitor cell (i.e. without traversing through a well-differentiated phase), in which case they would have manifested earlier because of their higher mitotic rate. EMT involves changes whereby epithelial cells disassemble their junctional structures, express mesenchymal proteins, remodel their extracellular matrix, lose polarity, and become more migratory. This phenotypic switch is a key process in development, and also occurs during tissue regeneration and organ fibrosis, usually in response to an inflammatory process (reviewed in (Kalluri and Weinberg 2009)). Cancer cells use this property of epithelial cells to enhance their invasive and metastatic potential and render them more resistant to apoptotic cues. Accordingly, cells within the invasive front of human thyroid cancers have gene expression changes consistent with EMT when compared to cells in the central part of the tumor (Vasko et al. 2007). In addition, loss of E-cadherin, a hallmark of EMT, is a marker of progression from differentiated to undifferentiated thyroid cancers (Wiseman et al. 2007), a finding that we confirmed in our tissue microarray experiment. Moreover, a transcriptomic comparison of differentiated and dedifferentiated thyroid tumors found E-cadherin to be among the top genes that distinguished between these histotypes (Montero-Conde et al. 2008).

The full spectrum of triggering events that contribute to EMT in tumor cells is not completely understood. Alterations that occur during the course of primary tumor formation may sensitize them to EMT-inducing signals that arise during tumor progression, including expression of growth factors such as HGF, EGF, PDGF, and TGFβ (Jechlinger et al. 2002; Peinado et al. 2007; Weinberg 2008). The expression profile of the paired specimens did not yield a clear signature of activation of any of these growth factors or cytokines, with the exception of TGFβ, which scored robustly in one of the datasets we used to interrogate the arrays. The pattern of genes activated in response to TGFβ is notoriously variable because of the presence of distinct transcriptional partners of Smad in different cell types and conditions, which define synexpression groups that are highly context-dependent (Massague 2008; Gomis et al. 2006), and which may account for the lack of uniformity of TGFβ expression signatures between databases.

The presence of nuclear pSmad staining in PDTC provides evidence for a stage-specific activation of TGFβ. There was a marked increase in the number of TAMs in PDTCs, which express high levels of TGFβ (Fig 2D, (Savage et al. 2008)). As is the case for other epithelial lineages, TGFβ is not by itself sufficient to convert normal thyroid cells to a mesenchymal phenotype. TGFβ inhibits thyroid cell growth induced by TSH or growth factors in non-transformed rat and normal porcine thyroid cells, respectively (Morris, III et al. 1988; Tsushima et al. 1988). The proposed mechanism of growth impairment by TGFβ is through interference with the association of the cyclin D3/cdk4 holoenzyme with p27 kip1 (Depoortere et al. 2000).

Of note, a correlation between TGFβ signaling and EMT was also found in human PDTC and ATC (Montero-Conde et al. 2008). The execution of the EMT program in response to TGFβ depends on priming events occurring during tumor microevolution (reviewed in (Tse and Kalluri 2007)). Braf-induced thyroid cancer is driven primarily by constitutive activation of the classical MAPK pathway, as demonstrated by the sensitivity of BRAF-mutated thyroid cancer cell lines to MEK inhibitors (Leboeuf et al. 2008; Ball et al. 2007). Our data in primary cultures of PTC cells from Tg-Braf mice shows that they are already primed for TGFβ-induction of EMT, and that this is mediated via MAPK activation, since the process is prevented by treatment with a MEK inhibitor. The role of TGFβ as a triggering event for EMT has also been demonstrated in immortalized rat thyroid PCCL3 cells overexpressing oncogenic Braf (Riesco-Eizaguirre et al. 2009). In these cells TGFβ-induced EMT was also blocked by MEK inhibition. This has also been reported in the mammary gland epithelial cell line NMuMG, in which EMT was blocked by inhibition of MEK, but in contrast to our results this was not associated with changes in TGFβ-induced Smad phosphorylation (Xie et al. 2004).

Smads are potential convergence nodes for TGFβ and MAPK signaling. Smad2 is phosphorylated by ERK at multiple sites in the hinge domain (T220, S245, S250) and at T8 in the MH1 domain (Funaba et al. 2002; Wrighton et al. 2009). The functional consequences of MAPK phosphorylation of Smads appears to be context-dependent, although the role of each individual site in different cell types has not been carefully mapped. Whereas most of the ERK substrates in the hinge domain are also phosphorylated by multiple other kinases, T8 phosphorylation is largely controlled by ERK, and therefore serves as a useful readout of the activity of MAPK. Accordingly, pT8 Smad2 was markedly increased in thyroid cells from Tg-Braf mice, and inhibited by treatment with U0126. The canonical TGFβ receptor Smad phosphorylation sites at the C terminus SXS motifs track closely with transcriptional activation. Interestingly, TGFβ-induced SXS phosphorylation was decreased by inhibition of MEK activity in both wild type and Tg-Braf cells, as did Smad transcriptional output.

As reported in other cancer lineages, the ultimate effects of TGFβ on thyroid cell growth may vary according to the stage of tumor development (Tang et al. 2003). During early stages of clonal expansion cells may need to bypass growth inhibitory and apoptotic signals mediated by TGFβ. This can be done through a loss of the core pathway (i.e. TGFβ receptor mutations) or selective amputation of the growth inhibitory/apoptotic arm of the pathway. In the thyroid this has been proposed to be mediated through a variety of mechanisms, including NF-κB activation (Bravo et al. 2003). In some cancers when the core TGFβ signaling pathway remains intact, the tumor can utilize the pro-tumor attributes of the TGFβ pathway to promote progression (i.e. autocrine mitogens, pro-metastatic cytokines, immune evasion and EMT). For example a TGFβ-response signature was found to be associated with lung metastases in ER negative breast cancers (Padua et al. 2008). The data reported in this spontaneously-developing model of thyroid cancer progression shows that the growth inhibitory and pro-apoptotic action of TGFβ, if present, are bypassed via mechanisms that leave the core TGFβ signaling pathway intact, allowing at least some components of TGFβ signaling to be engaged during disease progression and be co-opted to promote EMT. Taken together with recent evidence that TGFβ may contribute to the impairment of iodine transport in thyroid cells induced by oncogenic Braf (Riesco-Eizaguirre et al. 2009), a legitimate case can now be made that targeting TGFβ signaling in advanced thyroid cancers may be of therapeutic benefit.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experimental animals

Tg-Braf mice, which express BrafV600E under the control of the bovine thyroglobulin promoter, have been described (Knauf et al. 2005), and were the primary model used in this study. LSL-BrafV600E/TPO-Cre mice, which harbor a latent oncogenic Braf knock-in allele activated in thyroid cells via Cre-mediated recombination (Franco et al. 2011), were crossed with ROSA26-EGFPf/f mice (Mao et al. 2001) resulting in expression of GFP in only the Braf-transformed thyroid cells, which allowed FACS analysis of thyroid cancer and stromal cell subpopulations. All animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees of the University of Cincinnati and Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center.

Thyroid collection and laser capture microdissection

Animals were euthanized with CO2 and thyroids collected and immediately frozen in OTC. H&E-stained frozen sections were examined by a thyroid pathologist (YEN) for identification of discrete foci of well differentiated papillary thyroid cancer (PTC) and poorly differentiated thyroid cancer (PDTC). Slides were stained with HistoGene™ LCM Frozen Section Staining Kit (Arcturus Bioscience, Mountain View, CA) and cells from the PDTC focus and a representative region of PTC were micro-isolated using the Arcturus PixCell II laser capture microscope System. RNA was isolated from the laser captured cells using PicoPure™ RNA Isolation Kit (Arcturus Bioscience) and then subjected to two rounds of mRNA amplification using the messageAMP RNA amplification kit (Ambion, Austin, TX).

Mouse microarray hybridizations and analysis

Expression profiling was performed with chips arrayed with the 70-mer mouse oligonucleotide Operon Library Version MEEBO v1.05 (35,302 oligos) (Operon Biotechnologies; Huntsville, AL). Fluorescently-labeled antisense RNAs (aRNA)s obtained from the microdissected tissue specimens were used for microarray hybridization. The aRNA was generated by reverse transcription of RNA via an oligo(dT)-primer bearing a T7 promoter, followed by in vitro transcription of the resulting cDNA using amino allyl modified UTP. The aRNAs were labeled with monofunctional reactive cyanine-3 and cyanine-5 dyes (Cy3 and Cy5; Amersham, Piscataway, NJ), for the PTC and PDTC from each paired sample, respectively. Co-hybridizations were done in triplicate with a single dye flip. Imaging and data generation were carried out using a GenePix 4000A and GenePix 4000B (Axon Instruments, Union City, CA) and associated software from Axon Instruments, Inc. (Foster City, CA). The microarray slides were scanned with dual lasers with wavelength frequencies to excite Cy3 and Cy5 fluorescence emittance. Images were stored in JPEG and TIFF files, and DNA spots were captured by the adaptive circle segmentation method. Information extraction for a given spot is based on the median value for the signal pixels minus the median value for the background pixels to produce a gene set data file for all the DNA spots. Data normalization was performed in two steps (Guo et al. 2004). First, background-adjusted intensities were log transformed, and the differences (R) and averages (A) of log-transformed values were calculated as R=log2(X1)−log2(X2 and A=[log2(X1)+log2(X2)]/2, where X1 and X2 denote the Cy5 and Cy3 intensities after subtracting local backgrounds, respectively. Second, data centering was done by fitting the array-specific local regression model of R as a function of A. The difference between the observed log-ratio and the corresponding fitted value represented the normalized log-transformed gene expression ratio. The statistical analysis was done for each gene separately by fitting a mixed-effects model including biological replicate as a random factor and ensuring the correct denominator degrees of freedom. Estimated fold changes were calculated for appropriate contrasts, and statistical significance of differential expression was assessed using an intensity-based empirical Bayes method (IBMT) (Sartor et al. 2006), calculating P-values, and adjusting for multiple hypotheses testing using the false discovery rate method (Benjamini and Hochberg 1995; Reiner et al. 2003). An FDR cutoff level of 0.10 was used for significance. Preprocessing and data normalization were performed using R statistical platform and the limma package of Bioconductor (Smyth 2004).

Human microarray hybridizations and analysis

The array analyzed has been previously described (Giordano et al. 2005). To identify genes differentially expressed in ATC versus PTC we first used the custom Entrez cdf package (Dai et al. 2005) to map probes to probe sets, and then performed all pre-processing and normalization using RMA in Bioconductor. Differential expression was tested using a moderated T-test (IBMT) and adjusting for multiple testing using the false discovery rate method.

Immunohistochemistry

Thyroid glands were fixed in 4% PFA at 4°C for 24 hours, and then in 70% ethanol before embedding them in paraffin. Sections were immunostained with antibodies to phospho (S465/467) Smad2 (3108) or E-cadherin (3195) from Cell Signaling (Beverly, MA), vimentin (ab7783, Abcam, Cambridge, MA) or MAC-2 (CL8942B, Cedarlane, Burlington, Ontario, Canada) with the help of MSKCC Molecular Cytology core facility (pSmad2) or Genetically Engineered Mouse Phenotyping core facility (MAC2, E-cadherin, and vimentin). The human thyroid cancer tissue microarray has been previously described (Saltman et al. 2006).

Primary cultures of thyroid cells

Thyroid lobes were isolated, washed with 1× PBS and then with digestion medium (MEM+112 U/ml type I collagenase, 1.2 U/ml dispase, and penicillin/streptomycin). The thyroids were then minced and incubated in digestion medium for 1 hour at 37°C and washed with growth medium consisting of Coon's modified F12 medium containing 2mIU/ml bovine TSH, 20 μg/ml insulin, 10 μg/ml apo-transferrin, 2nM hydrocortisone, 3% fetal bovine serum, 0.5% bovine brain extract (Hammond Cell Tech, Windsor, CA), penicillin and streptomycin. Cells were resuspended and plated into CellBind plates or collagen-coated chamber slides. The thyroid cancer cell line is an immortalized murine thyroid cancer cell line that was created from a transgenic mouse with thyroid-specific expression of BrafV600E and loss of p53. mBraf-p53 cells were grown in Coon's modified F12 medium containing 5% fetal bovine serum, 0.5% bovine brain extract (Hammond Cell Tech, Windsor, CA), penicillin and streptomycin.

Isolation of TAMs and thyroid cancers cells

Thyroid lobes from LSL-BrafV600E/TPO-Cre/ROSA26-EGFPf/f were washed with 1× PBS and then with digestion medium (MEM+112 U/ml type I collagenase, 1.2 U/ml dispase, and penicillin/streptomycin). The thyroids were then minced and incubated in digestion medium for 2 h at 37°C and washed with Coon's modified F12 medium containing 5% fetal bovine serum and penicillin and streptomycin. Cells were blocked with Fc-receptor and then stained with APC conjugated rat anti-CD11b (BD, Biosciences cat# 553312), a molecular marker of macrophages. The TAMs and GFP positive thyroid cancer cells were isolated by flow cytometry and RNA isolated from the two cell populations using PicoPure™ RNA Isolation Kit (Arcturus Bioscience). qRT-PCR was performed as described below.

Western blotting

Thyroid cell primary cultures were incubated in CellBind plates with growth medium containing the indicated concentration of TGFβ and U0126. Cells were then washed with ice-cold PBS, and harvested by scraping and centrifugation (1000 × g for 4 minutes at 4°C). The cell pellets were resuspended in a lysis buffer consisting of 10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 5.0 mM ETDA, 4.0 mM EGTA, 1% Triton X100, protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma), phosphatase inhibitor cocktail A & B (Sigma) and cells lysed by passing through a p200 tip, and cell debris removed by centrifugation. The supernatant was collected and the protein concentration determined using MicroBCA kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL). Fifty micrograms of protein lysate was subjected to SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membranes. The membranes were probed with the indicated antibody and the target protein detected by incubating with species-specific horseradish peroxidase conjugated IgG's and then with enhanced chemiluminescence reagent (Amersham Biosciences Corp, Piscataway, NJ). Images were captured using the LAS4000 (Fujifilm Medical Systems, Stamford, CT). The following antibodies were used phospho (Thr202/Tyr204) ERK1/2 (4376), ERK1/2 (4695), α/β-tubulin (2148) and phospho (Ser465/467) Smad2 from Cell Signaling (Beverly, MA); Smad2/3 (sc-8332) from Santa Cruz (Santa Cruz, CA); Smad2 (ab63576) and phospho(T8)-Smad2/3 (ab63399) from Abcam (Cambridge, MA).

Quantitative RT-PCR

RNA was isolated from cells using Prepease RNA spin kit (USB Corporation, Cleveland, OH). Reverse transcription and quantitative PCR was performed using the Superscript III First-Strand Synthesis system (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and Fast SYBR® Green Master Mix as directed by the manufacturer (Applied Biosystems Inc., Foster City, CA), respectively (see Supplementary Table 5 for primer pair sequences). The CT value was used to calculate the β-actin-normalized expression of the different mRNAs using the Q-Gene program (Muller et al. 2002).

3TP-Lux promoter assay

Primary cultures of thyroid cells from Tg-Braf and wild-type mice were incubated in growth medium until ~80% confluent, and then transfected with CMV-Renilla and either 3TP-Lux, pGL3-basic, or pGL3-control using Fugene6 (Roche, Indianapolis, IN). The TGFβ-responsive 3TP-Lux construct contains three repeats of a 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol 13-acetate responsive element plus the plasminogen activator inhibitor promoter linked to a luciferase reporter gene (Wrana et al. 1992). Luciferase activity was determined using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega, Madison, WI). Firefly luciferase activity was normalized to CMV-Renilla and subtracted from normalized luciferase activity in cells transfected with pGL3-Basic.

Immunofluorescence cytochemistry

Tg-Braf and wild-type thyroid primary culture cells were plated onto collagen-coated chamber slides and incubated for 2–3 days. Cells were then changed to growth medium with or without TGFβ and the indicated reagents for 6 days. Cells were then washed with ice-cold PBS and fixed in −20°C methanol/acetone (1:1) for 4 minutes. Slides were then washed, incubated in PBS containing 10% goat serum and 0.1% Triton ×100 for 30 minutes and then in PBS with 1% goat serum and 0.05% Triton ×100 with the indicated primary antibodies for 2 hours. After washing, slides were then incubated for 30 minutes with Alexa488 and Alexa647-conjugated goat anti-mouse and anti-rabbit antibodies, respectively. The slides were then washed and the nuclei stained with DAPI. Images were captured using Nikon Eclipse TE2000 (Nikon Instruments Inc.). The following antibodies were used mouse anti E-Cadherin (610182) from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA), mouse anti Vimentin (V5255) from Sigma (St. Louis, MO) and rabbit anti Cytokeratin (Z0622) from Dako (Carpinteria, CA).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Supported by NIH CA 50706, and a grant from the Margot Rosenberg Pulitzer Foundation. We are grateful to the MSKCC Genetically Engineered Mouse Phenotyping core facility and Dr. Katia Manova of the MSKCC Molecular Cytology core for help with immunohistochemical experiments.

Reference List

- Ball DW, Jin N, Rosen DM, Dackiw A, Sidransky D, Xing M, et al. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:4712–4718. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society B. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Bravo SB, Pampin S, Cameselle-Teijeiro J, Carneiro C, Dominguez F, Barreiro F, et al. Oncogene. 2003;22:7819–7830. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai M, Wang P, Boyd AD, Kostov G, Athey B, Jones EG, et al. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:e175. doi: 10.1093/nar/gni179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Depoortere F, Pirson I, Bartek J, Dumont JE, Roger PP. Mol Biol Cell. 2000;11:1061–1076. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.3.1061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derynck R, Zhang YE. Nature. 2003;425:577–584. doi: 10.1038/nature02006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elisei R, Ugolini C, Viola D, Lupi C, Biagini A, Giannini R, et al. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:3943–3949. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-0607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagin JA, Matsuo K, Karmakar A, Chen DL, Tang SH, Koeffler HP. J Clin Invest. 1993;91:179–184. doi: 10.1172/JCI116168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franco AT, Malaguarnera R, Refetoff S, Liao XH, Lundsmith E, Kimura S, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1015557108. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funaba M, Zimmerman CM, Mathews LS. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:41361–41368. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204597200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giordano TJ, Kuick R, Thomas DG, Misek DE, Vinco M, Sanders D, et al. Oncogene. 2005;24:6646–6656. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomis RR, Alarcon C, He W, Wang Q, Seoane J, Lash A, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:12747–12752. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605333103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo J, Sartor M, Karyala S, Medvedovic M, Kann S, Puga A, et al. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2004;194:79–89. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2003.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue Y, Imamura T. Cancer Sci. 2008;99:2107–2112. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2008.00925.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jechlinger M, Grunert S, Beug H. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2002;7:415–432. doi: 10.1023/a:1024090116451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalluri R, Weinberg RA. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:1420–1428. doi: 10.1172/JCI39104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura ET, Nikiforova MN, Zhu Z, Knauf JA, Nikiforov YE, Fagin JA. Cancer Res. 2003;63:1454–1457. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knauf JA, Ma X, Smith EP, Zhang L, Mitsutake N, Liao XH, et al. Cancer Res. 2005;65:4238–4245. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leboeuf R, Baumgartner JE, Benezra M, Malaguarnera R, Solit D, Pratilas CA, et al. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:2194–2201. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-2825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MK, Pardoux C, Hall MC, Lee PS, Warburton D, Qing J, et al. EMBO J. 2007;26:3957–3967. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin X, Liang M, Feng XH. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:36818–36822. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C000580200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao X, Fujiwara Y, Chapdelaine A, Yang H, Orkin SH. Blood. 2001;97:324–326. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.1.324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massague J. Cell. 2008;134:215–230. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montero-Conde C, Martin-Campos JM, Lerma E, Gimenez G, Martinez-Guitarte JL, Combalia N, et al. Oncogene. 2008;27:1554–1561. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris JC, III, Ranganathan G, Hay ID, Nelson RE, Jiang NS. Endocrinology. 1988;123:1385–1394. doi: 10.1210/endo-123-3-1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller PY, Janovjak H, Miserez AR, Dobbie Z. Biotechniques. 2002;32:1372–1379. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Namba H, Nakashima M, Hayashi T, Hayashida N, Maeda S, Rogounovitch TI, et al. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:4393–4397. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-030305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikiforova MN, Kimura ET, Gandhi M, Biddinger PW, Knauf JA, Basolo F, et al. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:5399–5404. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-030838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padua D, Zhang XH, Wang Q, Nadal C, Gerald WL, Gomis RR, et al. Cell. 2008;133:66–77. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peinado H, Olmeda D, Cano A. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:415–428. doi: 10.1038/nrc2131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiner A, Yekutieli D, Benjamini Y. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:368–375. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btf877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricarte-Filho JC, Ryder M, Chitale DA, Rivera M, Heguy A, Ladanyi M, et al. Cancer Res. 2009;69:4885–4893. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riesco-Eizaguirre G, Rodriguez I, De l, V, Costamagna E, Carrasco N, Nistal M, et al. Cancer Res. 2009;69:8317–8325. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryder M, Ghossein RA, Ricarte-Filho JC, Knauf JA, Fagin JA. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2008;15:1069–1074. doi: 10.1677/ERC-08-0036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saltman B, Singh B, Hedvat CV, Wreesmann VB, Ghossein R. Surgery. 2006;140:899–906. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2006.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sartor MA, Leikauf GD, Medvedovic M. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:211–217. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sartor MA, Mahavisno V, Keshamouni VG, Cavalcoli J, Wright Z, Karnovsky A, et al. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:456–463. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sartor MA, Tomlinson CR, Wesselkamper SC, Sivaganesan S, Leikauf GD, Medvedovic M. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006;7:1–17. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savage ND, de BT, Walburg KV, Joosten SA, van MK, Geluk A, et al. J Immunol. 2008;181:2220–2226. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.3.2220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo SR, Lallemand F, Ferrand N, Pessah M, L'Hoste S, Camonis J, et al. EMBO J. 2004;23:3780–3792. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smyth GK. Stat Appl Genet Mol Biol. 2004;3:1–25. doi: 10.2202/1544-6115.1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soares P, Trovisco V, Rocha AS, Lima J, Castro P, Preto A, et al. Oncogene. 2003;22:4578–4580. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang B, Vu M, Booker T, Santner SJ, Miller FR, Anver MR, et al. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:1116–1124. doi: 10.1172/JCI18899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tse JC, Kalluri R. J Cell Biochem. 2007;101:816–829. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsushima T, Arai M, Saji M, Ohba Y, Murakami H, Ohmura E, et al. Endocrinology. 1988;123:1187–1194. doi: 10.1210/endo-123-2-1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasko V, Espinosa AV, Scouten W, He H, Auer H, Liyanarachchi S, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:2803–2808. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610733104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg RA. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:1021–1023. doi: 10.1038/ncb0908-1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiseman SM, Griffith OL, Deen S, Rajput A, Masoudi H, Gilks B, et al. Arch Surg. 2007;142:717–727. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.142.8.717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wrana JL, Attisano L, Carcamo J, Zentella A, Doody J, Laiho M, et al. Cell. 1992;71:1003–1014. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90395-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wrighton KH, Lin X, Feng XH. Cell Res. 2009;19:8–20. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie L, Law BK, Chytil AM, Brown KA, Aakre ME, Moses HL. Neoplasia. 2004;6:603–610. doi: 10.1593/neo.04241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xing M. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2005;12:245–262. doi: 10.1677/erc.1.0978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J, Lamouille S, Derynck R. Cell Res. 2009;19:156–172. doi: 10.1038/cr.2009.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.