Abstract

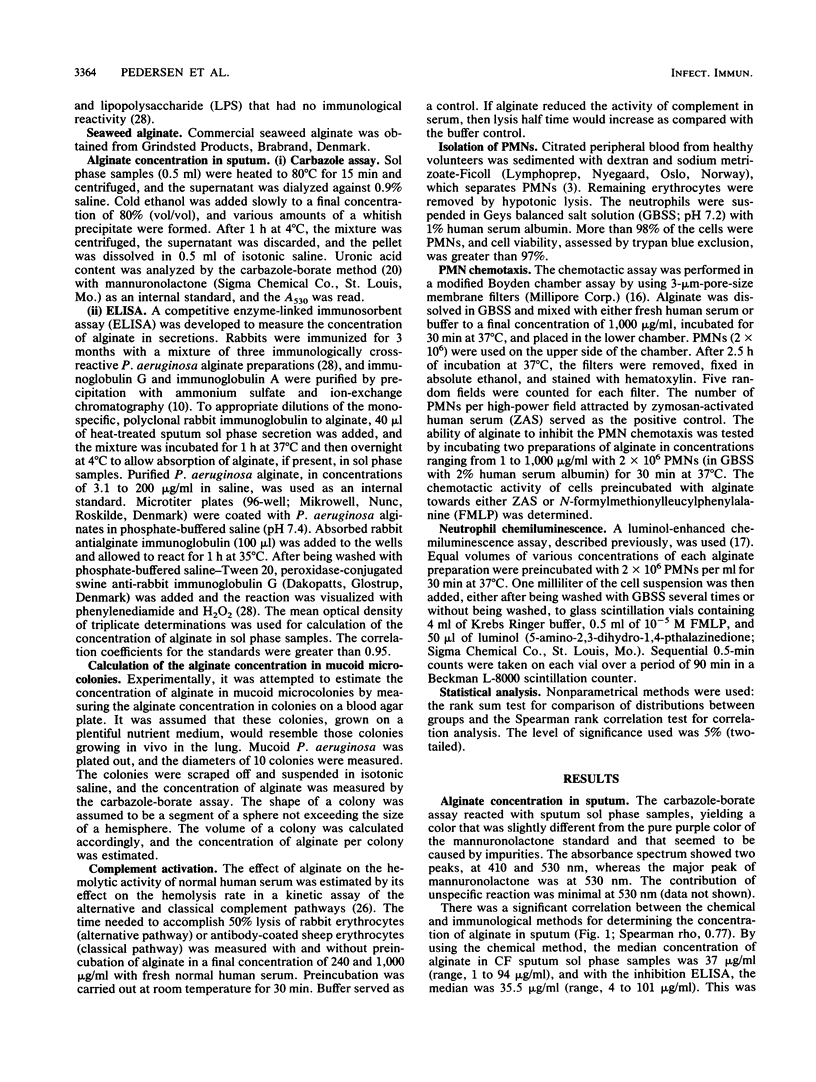

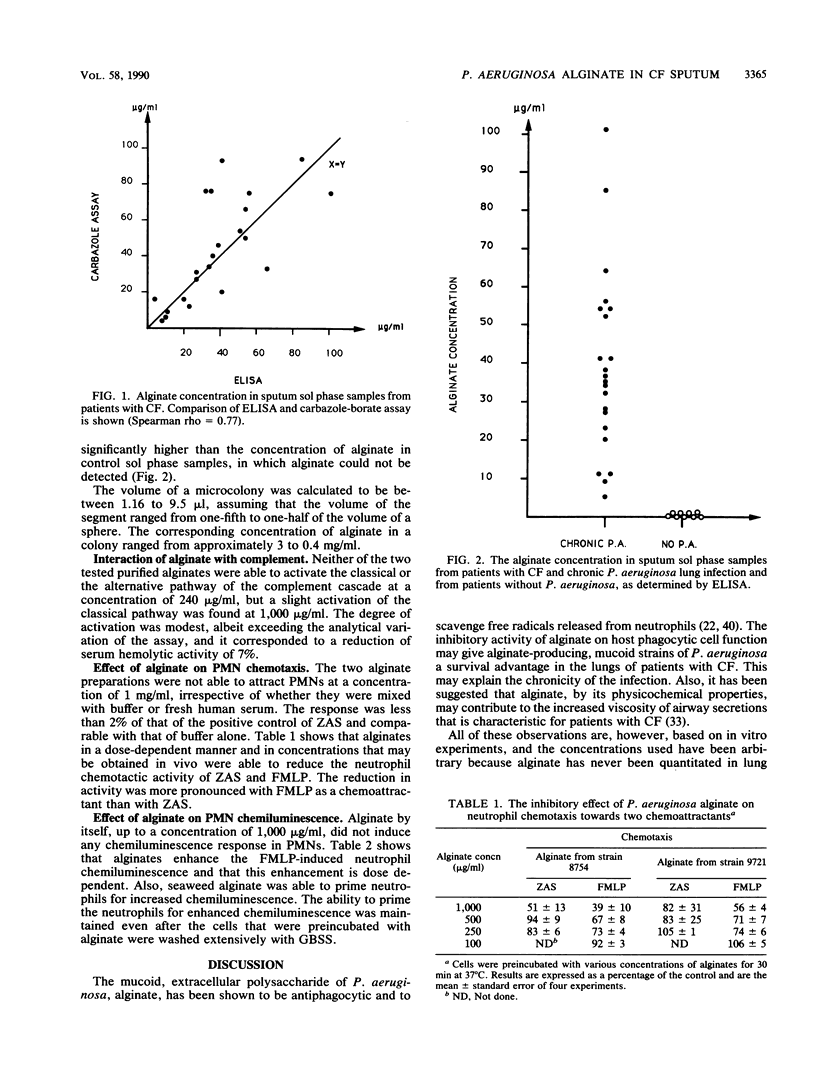

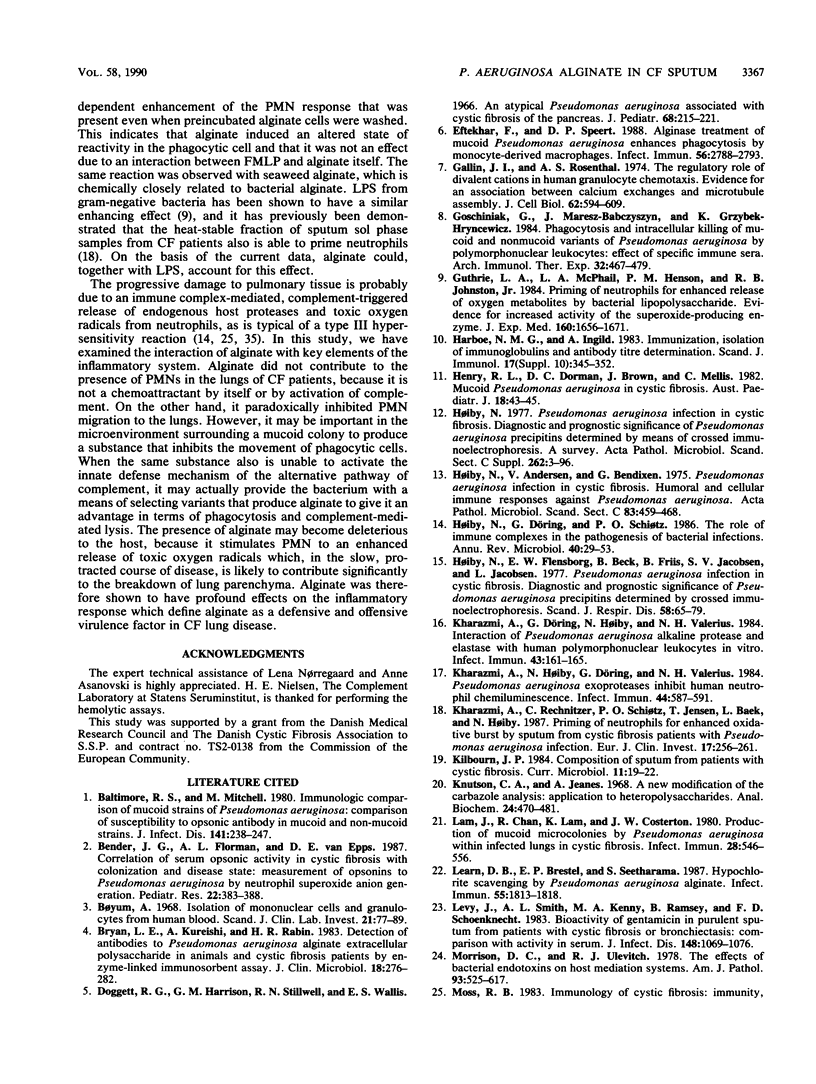

Alginate, a viscous polysaccharide from mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa, may interfere with the host defenses in patients with cystic fibrosis and chronic P. aeruginosa lung infection. The alginate concentration in the sol phase of expectorated sputum was quantitated by a biochemical method and a newly developed enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. There was a high degree of correlation between the methods, and the concentration of alginate ranged from 4 to 101 micrograms/ml with a median of 35.5 micrograms/ml when measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Alginate could not be detected in the bronchial secretions from patients without P. aeruginosa infection. In vitro investigation of alginate did not show any activation of the alternative pathway of complement, as determined by a hemolytic kinetic assay and by testing for neutrophil chemotaxis. At a high concentration, P. aeruginosa alginate caused a slight activation of the classical pathway of complement. Alginate did not cause neutrophil chemotaxis by itself but was able to reduce the neutrophil chemotactic response to N-formylmethionylleucylphenylalanine and for zymosan-activated serum. P. aeruginosa and seaweed alginates were able to prime neutrophils for increased N-formylmethionylleucylphenylalanine-induced neutrophil oxidative burst, as determined by chemiluminescence. Because of its ability to prevent attraction of neutrophils to the site of infection, lack of complement activation, and ability to enhance neutrophil oxidative burst, alginate from P. aeruginosa may contribute to the persistence and pathogenesis of chronic P. aeruginosa infection in cystic fibrosis.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Baltimore R. S., Mitchell M. Immunologic investigations of mucoid strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa: comparison of susceptibility to opsonic antibody in mucoid and nonmucoid strains. J Infect Dis. 1980 Feb;141(2):238–247. doi: 10.1093/infdis/141.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bender J. G., Florman A. L., Van Epps D. E. Correlation of serum opsonic activity in cystic fibrosis with colonization and disease state: measurement of opsonins to Pseudomonas aeruginosa by neutrophil superoxide anion generation. Pediatr Res. 1987 Oct;22(4):383–388. doi: 10.1203/00006450-198710000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan L. E., Kureishi A., Rabin H. R. Detection of antibodies to Pseudomonas aeruginosa alginate extracellular polysaccharide in animals and cystic fibrosis patients by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. J Clin Microbiol. 1983 Aug;18(2):276–282. doi: 10.1128/jcm.18.2.276-282.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eftekhar F., Speert D. P. Alginase treatment of mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa enhances phagocytosis by human monocyte-derived macrophages. Infect Immun. 1988 Nov;56(11):2788–2793. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.11.2788-2793.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallin J. I., Rosenthal A. S. The regulatory role of divalent cations in human granulocyte chemotaxis. Evidence for an association between calcium exchanges and microtubule assembly. J Cell Biol. 1974 Sep;62(3):594–609. doi: 10.1083/jcb.62.3.594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gościniak G., Maresz-Babczyszyn J., Grzybek-Hryncewicz K. Phagocytosis and intracellular killing of mucoid and nonmucoid variants of Pseudomonas aeruginosa by polymorphonuclear leukocytes: effect of specific immune sera. Arch Immunol Ther Exp (Warsz) 1984;32(4):467–479. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guthrie L. A., McPhail L. C., Henson P. M., Johnston R. B., Jr Priming of neutrophils for enhanced release of oxygen metabolites by bacterial lipopolysaccharide. Evidence for increased activity of the superoxide-producing enzyme. J Exp Med. 1984 Dec 1;160(6):1656–1671. doi: 10.1084/jem.160.6.1656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry R. L., Dorman D. C., Brown J., Mellis C. Mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa in cystic fibrosis. Aust Paediatr J. 1982 Mar;18(1):43–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.1982.tb01979.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoiby N., Flensborg E. W., Beck B., Friis B., Jacobsen S. V., Jacobsen L. Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection in cystic fibrosis. Diagnostic and prognostic significance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa precipitins determined by means of crossed immunoelectrophoresis. Scand J Respir Dis. 1977 Apr;58(2):65–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Høiby N., Döring G., Schiøtz P. O. The role of immune complexes in the pathogenesis of bacterial infections. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1986;40:29–53. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.40.100186.000333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kharazmi A., Döring G., Høiby N., Valerius N. H. Interaction of Pseudomonas aeruginosa alkaline protease and elastase with human polymorphonuclear leukocytes in vitro. Infect Immun. 1984 Jan;43(1):161–165. doi: 10.1128/iai.43.1.161-165.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kharazmi A., Høiby N., Döring G., Valerius N. H. Pseudomonas aeruginosa exoproteases inhibit human neutrophil chemiluminescence. Infect Immun. 1984 Jun;44(3):587–591. doi: 10.1128/iai.44.3.587-591.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kharazmi A., Rechnitzer C., Schiøtz P. O., Jensen T., Baek L., Høiby N. Priming of neutrophils for enhanced oxidative burst by sputum from cystic fibrosis patients with Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection. Eur J Clin Invest. 1987 Jun;17(3):256–261. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.1987.tb01245.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam J., Chan R., Lam K., Costerton J. W. Production of mucoid microcolonies by Pseudomonas aeruginosa within infected lungs in cystic fibrosis. Infect Immun. 1980 May;28(2):546–556. doi: 10.1128/iai.28.2.546-556.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Learn D. B., Brestel E. P., Seetharama S. Hypochlorite scavenging by Pseudomonas aeruginosa alginate. Infect Immun. 1987 Aug;55(8):1813–1818. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.8.1813-1818.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy J., Smith A. L., Kenny M. A., Ramsey B., Schoenknecht F. D. Bioactivity of gentamicin in purulent sputum from patients with cystic fibrosis or bronchiectasis: comparison with activity in serum. J Infect Dis. 1983 Dec;148(6):1069–1076. doi: 10.1093/infdis/148.6.1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Maza O., Fehniger T. E., Ashman R. F. Antibody-secreting cell precursor frequencies among the sheep-erythrocyte-binding cells after immunization. Scand J Immunol. 1983 Apr;17(4):345–354. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.1983.tb00799.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mogensen C. E. The glomerular permeability determined by dextran clearance using Sephadex gel filtration. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 1968;21(1):77–82. doi: 10.3109/00365516809076979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison D. C., Ulevitch R. J. The effects of bacterial endotoxins on host mediation systems. A review. Am J Pathol. 1978 Nov;93(2):526–618. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen H. E., Koch C. Congenital properdin deficiency and meningococcal infection. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1987 Aug;44(2):134–139. doi: 10.1016/0090-1229(87)90060-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver A. M., Weir D. M. The effect of Pseudomonas alginate on rat alveolar macrophage phagocytosis and bacterial opsonization. Clin Exp Immunol. 1985 Jan;59(1):190–196. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen S. S., Espersen F., Høiby N., Shand G. H. Purification, characterization, and immunological cross-reactivity of alginates produced by mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa from patients with cystic fibrosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1989 Apr;27(4):691–699. doi: 10.1128/jcm.27.4.691-699.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen S. S., Høiby N., Shand G. H., Pressler T. Antibody response to Pseudomonas aeruginosa antigens in cystic fibrosis. Antibiot Chemother (1971) 1989;42:130–153. doi: 10.1159/000417614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson P. K., Wilkinson B. J., Kim Y., Schmeling D., Douglas S. D., Quie P. G., Verhoef J. The key role of peptidoglycan in the opsonization of Staphylococcus aureus. J Clin Invest. 1978 Mar;61(3):597–609. doi: 10.1172/JCI108971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pier G. B., Matthews W. J., Jr, Eardley D. D. Immunochemical characterization of the mucoid exopolysaccharide of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Infect Dis. 1983 Mar;147(3):494–503. doi: 10.1093/infdis/147.3.494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruhen R. W., Holt P. G., Papadimitriou J. M. Antiphagocytic effect of Pseudomonas aeruginosa exopolysaccharide. J Clin Pathol. 1980 Dec;33(12):1221–1222. doi: 10.1136/jcp.33.12.1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell N. J., Gacesa P. Chemistry and biology of the alginate of mucoid strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in cystic fibrosis. Mol Aspects Med. 1988;10(1):1–91. doi: 10.1016/0098-2997(88)90002-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiller N. L., Joiner K. A. Interaction of complement with serum-sensitive and serum-resistant strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Infect Immun. 1986 Dec;54(3):689–694. doi: 10.1128/iai.54.3.689-694.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzmann S., Boring J. R. Antiphagocytic Effect of Slime from a Mucoid Strain of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Infect Immun. 1971 Jun;3(6):762–767. doi: 10.1128/iai.3.6.762-767.1971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson J. A., Smith S. E., Dean R. T. Alginate inhibition of the uptake of Pseudomonas aeruginosa by macrophages. J Gen Microbiol. 1988 Jan;134(1):29–36. doi: 10.1099/00221287-134-1-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson J. A., Smith S. E., Dean R. T. Scavenging by alginate of free radicals released by macrophages. Free Radic Biol Med. 1989;6(4):347–353. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(89)90078-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speert D. P., Dimmick J. E., Pier G. B., Saunders J. M., Hancock R. E., Kelly N. An immunohistological evaluation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa pulmonary infection in two patients with cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Res. 1987 Dec;22(6):743–747. doi: 10.1203/00006450-198712000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speert D. P. Host defenses in patients with cystic fibrosis: modulation by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Surv Synth Pathol Res. 1985;4(1):14–33. doi: 10.1159/000156962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens D., Lieberman M., McNitt T., Price J. Demonstration of uronic acid capsular material in the cerebrospinal fluid of a patient with meningitis caused by mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Clin Microbiol. 1984 Jun;19(6):942–943. doi: 10.1128/jcm.19.6.942-943.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stiver H. G., Zachidniak K., Speert D. P. Inhibition of polymorphonuclear leukocyte chemotaxis by the mucoid exopolysaccharide of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Clin Invest Med. 1988 Aug;11(4):247–252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]