Abstract

Purpose

Assessment of bronchoscopy usefulness for diagnosis and treatment in children suspected of foreign body aspiration.

Material and method

There were 27 boys and 18 girls in the age from 15 month to 14 years (average 5.5 years). Rigid bronchoscopy was performed under general anaesthesia. Assessment of the respiratory tract was done and in cases with foreign body bronchoscopic evacuation was executed. Medical records and video recordings of bronchoscopy procedures were subjected to retrospective analysis.

Results

In 28 children (62.2%) during bronchoscopy, foreign body aspiration recognized in 17 (37.8%) bronchoscopy cases was negative. In 27 patients, foreign bodies were removed. In one child, foreign body was evacuated during second bronchoscopy after preparing proper instrumentation. There were no complications in post-bronchoscopic period. Operating time was from 5 to 90 min, average time was noted to be 24 min. Average time of hospital stay was 2–3 days.

Conclusions

Aspiration of foreign body should be suspected in all cases of bronchopulmonary infection with atypical course. Bronchoscopy is the best diagnostic and therapeutic method in all suspicions of foreign body. In children rigid bronchoscopy is still the method of choice.

Keywords: Bronchoscopy, Foreign body aspiration, Children

Introduction

A foreign body aspirated into the respiratory tract constitutes a serious condition of the respiratory system, characterised by a considerable variability of medical history, symptoms and prognosis. In the majority of cases, the problem of the aspiration of a foreign body into the respiratory system affects children of 1–3 years old and it is less common in new-born babies and school children [1]. In the United States of America, the presence of a foreign body in the respiratory tract constitutes a direct cause of approximately 3,000 deaths an year, while in the group of children up to 3 years of age, it accounts for 7% of sudden deaths [2, 3]. The diagnostics and treatment of children with a foreign body in the respiratory tract is a complex process, which requires close cooperation of a paediatric, pulmonological and surgical team. The fundamental role in the algorithm of the therapeutic procedure is played by bronchoscopy.

The aim of the present paper is to share personal experiences of administering bronchoscopy as a diagnostic and therapeutic tool to children suspected of the aspiration of a foreign body.

Material and method

In the years 2000–2010 bronchoscopy was performed on 45 children suspected of the aspiration of a foreign body into the respiratory tract. 27 boys and 18 girls whose age ranged from 15 months to 14 years (the average of 5.5 years) underwent the treatment. Only six of the children were sent directly to a surgical unit with a view to performing bronchoscopy due to a suspected aspiration of a foreign body into the respiratory tract immediately after the incident (transferred from home). The remaining 39 patients were re-directed from paediatric or ENT units to have bronchoscopy performed due to intensifying symptoms of pulmonary infection and the lack of visible effects of previously applied treatment. Before being transferred, four of the patients were found to have the presence of foreign body, thanks to flexible bronchoscopy.

The patients were qualified for the procedure of bronchoscopy on the basis of preliminary examination, clinical symptoms and X-ray examination. From the clinical point of view, the predominant symptoms involved the unilateral ones indicating respiratory inflammation (wheezing and crepitations) or lowered vesicular murmur. X-ray examination confirmed signs of atelectasis and inflammation, or emphysema (check-valve effect) of a part of pulmonary parenchyma.

The procedure was invariably performed under general anaesthesia with the use of a rigid bronchoscope, which enables the ventilation of a patient. If the presence of a foreign body was confirmed, forceps were led into bronchoscope light in order to pick up the body and remove it from the bronchial tree.

Smaller foreign bodies were extracted through bronchoscope light, whereas bigger bodies, whose size exceeded the bronchoscope’s diameter, were removed together with the bronchoscope. In the case of numerous fine-sized foreign bodies or the remnants left after the extraction of a main body, they were removed with the use of a sucking–irrigating instrument. The control of the bronchial tree was invariably performed after the object had been removed. If the patient was observed to have inflammation in the area of the bronchial tree, accompanied by a considerably amount of mucus or pus, it was sucked out and a sample of slops was taken for further bacteriological examination. After the bronchoscope had been removed, the anaesthesiologist intubated the patient with a view to enabling the patient’s safe recovery from the general anaesthesia.

The patients were discharged from hospital after approximately 48–96 h of the inpatient treatment. The children who showed symptoms of pulmonary infection were directed to a paediatric-pulmonological ward.

The patients’ medical records, the records as well as video recordings of bronchoscopy procedures were subjected to retrospective analysis. The factors analysed included the age of the patients, the presence, location and type of the foreign body, complications arising during the course of the procedure and immediately after the procedure was complete, as well as the time of the procedure and inpatient treatment.

Results

The most common auscultatory changes involved the asymmetry of vesicular murmur, the intensification of vesicular murmur, wheezing and crepitations. They were observed in 38 out of 45 patients (84.44%).

A PA X-ray of the chest was done in the case of all the patients suspected of the aspiration of a foreign body, whereas computed tomography (CT) was applied in only four cases. The X-ray analysis confirmed that the majority of the children showed signs of unilateral pneumonia (Table 1) together or without concomitant changes (atelectasis, emphysema).

Table 1.

Changes verified by X-ray and/or CT

| Dominant changes verified by X-ray and/or CT | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| Inflammation–pneumonia | 34/45 (75.55) |

| Atelectasis | 15/45 (33.33) |

| Emphysema (check-valve effect) | 10/45 (22.22) |

| Shade of a foreign body | 3/44 (6.66) |

| Pneumomediastinum + pneumorachis | 1/44 (2.22) |

| Foreign body found in virtual bronchoscopy | 1/44 (2.22) |

| No changes | 8 (17.77) |

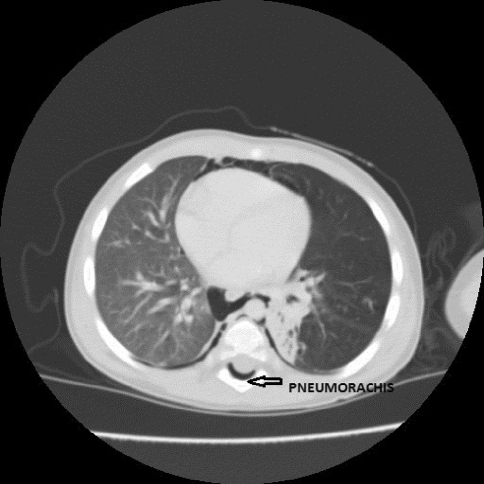

In three of the cases, the shade of a metallic foreign body could be noticed. One child suffering from micro-perforation of the left main bronchus showed in CT scans signs of pneumomediastinum and epidural emphysema (pneumorachis)—Fig. 1. In one of the patients, virtual bronchoscopy generated from the results of computer tomography made it possible to discern the foreign body present.

Fig. 1.

Epidural emphysema (pneumorachis) due to microperforation of left main bronchus

In 28 patients (62.22%), bronchoscopy confirmed the presence of a foreign body, while in the remaining 17 patients (37.77%) the result was negative. The preliminary examination had indicated that within the group of 28 patients, only 21 (75.0%) in whom bronchoscopy confirmed the presence of a foreign body.

Among the patients with a confirmed aspiration boys constituted the dominant group—60.71% (17 cases), whereas girls accounted for 39.28% (11 cases).

The average age of the patients with a confirmed aspiration was equivalent to 5.5 years (Table 2).

Table 2.

The age groups of children affected with the aspiration of a foreign body

| Age group | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| 1–5 years old | 19 (67.85) |

| 6–12 years old | 6 (21.42) |

| >12 years old | 3 (10.71) |

The location of a foreign body is presented in Table 3. In 19 of the cases (67.85%), a foreign body was noticed in the primary bronchus, whereas in 8 cases (28.57%) it made its way deeper into lobar bronchi or till the aperture to segmental bronchi. Only in one isolated case (3.57%) a foreign body got stuck in the trachea without causing a total occlusion.

Table 3.

The location of a foreign body

| Location | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| Left bronchial tree | 15 (53.57) |

| Right bronchial tree | 12 (42.85) |

| Trachea | 1 (3.57) |

Among the aspirated foreign bodies, 75% (21 cases) of them were organic, while the remaining 25% (seven cases) were inorganic. The types of foreign bodies are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

The type of an aspirated foreign body

| Type of a foreign body | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| A nut | 15 (53.57) |

| Plastic objects | 5 (17.85) |

| Sunflower seed or its shell | 4 (14.28) |

| Metal objects | 2 (7.14) |

| Chicken gristle | 1 (3.57) |

| Chewing gum | 1 (3.57) |

The most frequently aspirated foreign bodies were nuts or their parts—53.57%. Among plastic objects, the dominant ones were small elements of pens. In one case, the object noticed was a board game pawn. The metal objects found were a charm, a pin, and a pen element.

In 27 of the patients, the foreign body was removed during bronchoscopy and no complications arising during the course of the procedure were noted. In one case (the pen element stented and modelled the bronchus), it was impossible to extract the foreign body during the first bronchoscopy due to technical problems and intensified bleeding. After 2 days, when the necessary equipment was prepared (appropriate forceps) another bronchoscopy was performed, and foreign body was extracted without any complication. In a different case (the pin in the lumen of the right-side subsegmental bronchus B10b), a metal part of the foreign body was removed leaving the plastic element tightly adhering to the bronchus wall. In a case with bronchus microperforation, foreign body was removed and child did not need any additional intervention, epidural emphysema receded in a few days. In the period following the procedure, none of the patients was observed to develop surgical complications.

The time of the procedure ranged from 5 to 90 min, giving the average of 24 min. The average time of inpatient treatment amounted to 2–3 days.

Discussion

The location of a foreign body is dependent not only on its size and shape but also on the position taken by the child at the time when the aspiration takes place. In 50–60% of cases, the foreign body makes its way to the left bronchus, in 30–40% of cases it lodges in the right bronchus, whereas in 10–15% of cases it gets stuck in the trachea [4, 5]. In our study 53.57% of the foreign bodies could be found in the left bronchial tree, 42.85% in the right one, and only one object (3.57%) was localised in the trachea. The most commonly aspirated objects were nuts and sunflower seeds, accounting for 67.85% of the aspirated foreign bodies.

However, diagnostic imaging is still a controversial issue. In the material analysed, all the patients had an X-ray of the chest done. The main changes noticed included: a combination of inflammatory changes (75.55%), atelectasis (33.33%) and emphysema (22.22%). In only 6.66% of the patients, the shade of a foreign body was noticed. It should be emphasised that no changes detected in the X-ray examination does not rule out the presence of a foreign body in the bronchial tree. The negative result of the X-ray of the chest is normally true for 11–22% of children [6, 7]. In the group subject to analysis, the number was equal to 17.77%.

Computed tomography was administered to only four patients. The authors believe that a routine performance of tomography is unnecessary in the light of a generally accepted code of conduct—any suspicion of the aspiration of a foreign body qualifies a patient for diagnostic bronchoscopy. In order to avoid the necessity of performing bronchoscopy, some authors recommend virtual bronchoscopy during computed tomography [8, 9]. However, although virtual bronchoscopy is helpful in diagnosing the presence of a foreign body in the lumen of the respiratory tract, it does not solve the problem of object extraction.

According to the standards of contemporary bronchology, the aspiration of a foreign body into the respiratory tract, or even the suspicion of aspiration, as well as concomitant symptoms such as a cough, difficulty in breathing and raise in temperature constitute a direct indication for carrying out bronchoscopy [10, 11]. The issue which remains to be solved is the choice of examination technique. In the case of adults, flexible bronchoscopes are used both for diagnostic purposes and the extraction of a foreign body, the procedure being performed under local anaesthesia. In the case of children, especially the youngest ones, considering the necessity of general anaesthesia as well as mechanical ventilation to extract foreign bodies, the tool which is preferred in the majority of cases is a rigid bronchoscope [6, 10]. Furthermore, the latter is additionally equipped with appropriate instruments (forceps), enabling the extraction of a foreign body.

In the analysed material, diagnostic flexible bronchoscopy was performed on only four children during inpatient treatment at a paediatric or ENT ward. The presence of a foreign body was confirmed. However, on account of the impossibility of object extraction, the children were transferred to our clinic.

Divisi et al. [12] believe that the diagnostic effectiveness of flexible bronchoscopy reaches 100%, whereas the effectiveness of object extraction amounts to only 10%. It should be emphasised, however, that during the last couple of years the number of successful attempts to remove foreign bodies using flexible bronchoscopes has considerably increased. This has been facilitated by the technological development of endoscopes, as well as greater experience of teams performing the examination [13, 14]. There are units which claim 80–90% of success in extracting foreign bodies from children’s bronchial trees using the aforementioned technique [13]. One of the unquestionable advantages of flexible bronchoscopes is the possibility of reaching bronchi of smaller diameter, the segmental and subsegmental ones.

Despite all above-mentioned facts rigid bronchoscopy is still the best solution for the age group concerned [15, 16]. Not only does it ensure the possibility of general anaesthesia and controlled ventilation of a patient during the procedure, but also it limits the risk of complications [15]. Thus, it increases the level of the child’s safety, bringing additional comfort to the doctor performing the procedure. The application of a rigid bronchoscope was effective in each and every case, making it possible to extract the major parts of foreign bodies (using forceps) as well as to remove eventual remaining fragments from segmental bronchi (using forceps of a suction terminal).

The question that we are left with concerns the optimal time for performing bronchoscopy: whether it should be done immediately after the incident of aspiration or the suspicion thereof, or whether it should be postponed. Mani et al. [17] recommends performing bronchoscopy within 24 h from the moment of the incident in order to enable the possibility of performing the procedure in optimal conditions, so that the patient, the proper equipment and adequately trained team can get prepared for the procedure. Such an algorithm has also been accepted and implemented in our department. In the event of a suspected aspiration just after admission to the hospital, even though the preliminary examination or X-ray does not indicate any changes; rigid bronchoscopy was performed.

Most often, the aspiration of a foreign body affects children aged 2–5 [18, 19]. In the presented material, this age group accounted for more than 60% of the patients. The most commonly aspirated foreign bodies were nuts and sunflower seeds (about 68% of cases). Therefore, it is necessary to instruct parents and child-carers not to give any nuts or small seeds to pre-school children. Sure enough, prevention invariably serves better than treatment, even the best one.

Conclusions

The presence of a foreign body in the area of the bronchial tree is too rarely taken into account in the process of differentiation among pulmonary changes in children.

The aspiration of a foreign body should be suspected in each and every case of a pulmonary infection marked by ambiguous symptoms, especially with concomitant atelectasis or emphysema of some parts of pulmonary parenchyma.

In the event of a suspected aspiration, even if the preliminary examination or X-ray does not indicate any changes, bronchoscopy should be performed, since it constitutes the best diagnostic and therapeutic method under these circumstances.

In the case of children, rigid bronchoscopy still remains a technique of the first choice.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- 1.Berry FA, Yemen TA. Pediatric airway in health and disease. Pediatr Clin N Am. 1994;41(1):153–180. doi: 10.1016/s0031-3955(16)38697-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zerella JT, Dimler M, McGill LC, Pippus KJ. Foreign body aspiration in children: value of radiography and complications of bronchoscopy. J Pediatr Surg. 1998;33:1651–1654. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3468(98)90601-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baharloo F, Veyckemans F, Francis C, Biettlot MP, Rodenstein DO. Tracheobronchial foreign bodies: presentation and management in children and adults. Chest. 1999;115:1357–1362. doi: 10.1378/chest.115.5.1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhijun C, Fugao Z, Niankai Z, Jingjing C. Therapeutic experience from 1,428 patients with pediatric tracheobronchial foreign body. J Pediatr Surg. 2008;43(4):718–721. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2007.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tahir N, Ramsden WH, Stringer MD. Tracheobronchial anatomy and the distribution of inhaled foreign bodies in children. Eur J Pediatr. 2009;168(3):289–295. doi: 10.1007/s00431-008-0751-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cataneo AJ, Cataneo DC, Ruiz RJ., Jr Management of tracheobronchial foreign body in children. Pediatr Surg Int. 2008;24(2):151–156. doi: 10.1007/s00383-007-2046-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Girardi G, Contador AM, Costro-Rodriguez JA. Two new radiological findings to improve the diagnosis of bronchial foreign body aspiration in children. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2004;38(3):261–264. doi: 10.1002/ppul.20065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kocaoglu M, Bulakbasi N, Soylu K, Demirbag S, Tayfun C, Somuncu I. Thin-section axial multidetector computed tomography and multiplanar reformatted imaging of children with suspected foreign body aspiration: is virtual bronchoscopy overemphasized? Acta Radiol. 2006;47(7):746–751. doi: 10.1080/02841850600803834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang HJ, Fang HY, Chen HC, Wu CY, Cheng CY, Chang CL. Three-dimensional computed tomography for detection of tracheobronchial foreign body aspiration in children. Pediatr Surg Int. 2008;24(2):157–160. doi: 10.1007/s00383-007-2088-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jiaqiang S, Jingwu S, Yanming H, Qiuping L, Yinfeng W, Cinaguang L, Guanglun W, Demin H. Rigid bronchoscopy for inhaled pen caps in children. J Pediatr Surg. 2009;44(9):1708–1711. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2008.11.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cohen S, Avital A, Godfrey S, Gross M, Kerem E, Springer C. Suspected foreign body inhalation in children: what are the indications for bronchoscopy? J Pediatr. 2009;155(2):276–280. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Divisi D, Di Tommaso S, Garramone M, Di Francescantonio W, Crisci RM, Costa AM, Gravina GL, Crisci R. Foreign bodies aspirated in children: role of bronchoscopy. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2007;55(4):249–252. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-924714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tang LF, Cu YC, Wans YS, Wanf CF, Zhu GH, Bao XE, Lu MP, Chen LX, Chen ZM. Airway foreign body removal by flexible bronchoscopy: experience with 1,027 children during 2000–2008. World J Pediatr. 2009;5(3):191–195. doi: 10.1007/s12519-009-0036-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ramirez-Figueroa JL, Gochicoa-Rangel LG, Ramirez-San Juan DH, Bargas MH. Foreign body removal by flexible fibre-optic bronchoscopy in infants and children. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2005;40(5):392–397. doi: 10.1002/ppul.20242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tomaske M, Gerber AC, Weiss M. Anesthesia and peri-interventional morbidity of rigid bronchoscopy for tracheobronchial foreign body diagnosis and removal. Paediatr Anaesth. 2006;16(2):123–129. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9592.2005.01714.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zur KB, Litman RS. Pediatric airway foreign body retrieval: surgical and anesthetic perspectives. Paediatr Anaesth. 2009;19(1):109–117. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9592.2009.03006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mani N, Soma M, Massey S, Albert D, Bailey CM. Removal of inhaled foreign bodies—middle of the night or the next morning? Int J Pediatr Otorhi. 2009;73(8):1085–1089. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2009.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen LH, Zhang X, Li SQ, Liu YQ, Zhang TY, Wu JZ. The risk factors for hypoxemia in children younger than 5 years old undergoing rigid bronchoscopy for foreign body removal. Anesth Analg. 2009;109(4):1079–1084. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e3181b12cb5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brkić F, Umihanić S. Tracheobronchial foreign bodies in children. Experience at ORL clinic Tuzla 1954–2004. Int J Pediatr Otorhi. 2007;71(6):909–915. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2007.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]