Abstract

DNA experiences torsional stress resulting from the activities of motor enzymes and bound proteins. The mechanisms by which this torsional stress is dissipated to maintain DNA structural integrity are not fully known. Here, we show that a Holliday junction can limit torsion by coupling rotation to translocation and torque to force. The torque required to mechanically migrate through individual junctions was found to be an order of magnitude smaller than that required to melt DNA. We also directly show that substantially more torque was required to migrate through even a single-base sequence heterology, which has important implications for the activity of junction-migrating enzymes.

DNA structure is modulated dynamically throughout the cell cycle by DNA binding proteins and motor enzymes that constantly pull and twist the DNA strands. A DNA molecule typically assumes a B-form structure when relaxed but can undergo phase transitions to other structures upon stretching and twisting, and can adopt even more exotic configurations under certain circumstances. A four-way Holliday junction (Fig. 1 A, inset) is one such important nanoscopic DNA structure, formed during homologous recombination (1), double-stranded break repair (2,3), replication fork recovery (4), and at inverted repeat sequences (5). During junction migration, the four arms of a junction coordinate their relative rotations to allow efficient coupling of rotation to junction translation. Holliday junction migration may be enzymatically mediated by molecular motors or junction binding proteins (6), some of which have been shown to use ATP hydrolysis to bias directional branch migration (7). Even in the absence of motor enzymes and proteins, junction migration may take place spontaneously in a random-walk fashion due to a low energetic cost resulting from the nearly fully base-paired DNA structure preserved during this process (7,8). However, a single-base mismatch can nearly completely shut down spontaneous migration (9) and presents a substantial torsional barrier to migration. Such mismatches due to sequence heterologies are common in vivo. The RuvAB junction-assisting complex is known to promote migration through sequence heterologies (10), but the nature of the torsional barrier that it encounters has not been fully understood. In this work, we have directly measured the torque required to migrate through both a homologous and heterologous junction. This establishes the torque that motor proteins such as RuvAB must be capable of generating to migrate a junction.

Figure 1.

Experimental configuration and migration through a fully homologous Holliday junction. (A) A DNA tether with a preformed Holliday junction at its center was migrated under constant tension by rotation of a nanofabricated quartz cylinder using an angular optical trap. (Inset) Structure of a Holliday junction and directions of force and torque exerted on the vertical arms. (B) Individual extension and torque traces. Twenty negative turns were applied at ∼20 bp/s and then reversed, returning the junction to its original location. The end-to-end extension and the torque of each molecule were measured simultaneously. (C) Shown are the mean torque as a function of force (points) and theoretical prediction (line; not a fit).

To understand the mechanical coupling of rotation to translation and the resulting torque and force at the junction, we employed an angular optical trap (11–15) to mechanically migrate individual Holliday junctions. A 2.2-kbp palindromic DNA molecule with a preformed Holliday junction at its midpoint was torsionally constrained at the two opposite ends and held under a fixed force using an angular optical trap (Fig. 1 A and Fig. S1 in the Supporting Material). The Holliday junction was then migrated by rotation of a trapped nanofabricated quartz cylinder (11) in phosphate-buffered saline containing Na+ ions, but no Mg2+, to prevent the stacking of junction arms (16). This unstacked conformation is typically achieved in vivo by the presence of junction-bound proteins, such as Escherichia coli RuvA, which hold the junction in an open planar configuration (17), thereby enhancing prolonged smooth migration events. Note that winding experiments performed in the presence of Mg2+ yielded complex extension behavior, consistent with frequent stacking events occurring off the main migration pathway of interest in this work (Supporting Discussion and Fig. S3). The application of a tension along opposing DNA arms of the Holliday junction resulted in a biased junction migration to extend these arms and a simultaneous torque build-up in these arms resisting junction migration.

We first examined the migration of a fully homologous junction. For each negative full turn of the cylinder, the DNA extension decreased by ∼3.3 nm, as the DNA was converted from vertical arms to side arms (Fig. 1 B; also see Fig. S2). The migration was smooth and fully reversible, as evidenced by the extension signal, indicating the system was under thermodynamic quasiequilibrium. Previous studies on cruciform extrusion using magnetic tweezers yielded similar extension behavior, but that technique does not allow for direct torque measurement (18). During migration, we measured a very small torque on the DNA, as low as 0.5 pN nm, in the same sense as DNA underwinding (Fig. 1, B and C). The measured torque remained constant under a given force but depended strongly on the magnitude of the applied force. We found that a simple thermodynamic model can predict this force dependence, assuming known values for the bending and torsional elasticities of DNA (Fig. 1 C, red line). Details are given in the Supporting Discussion.

These results show that the torque required to mechanically migrate a fully homologous Holliday junction is at least an order of magnitude smaller than that required to melt dsDNA (∼–10 pN nm) (19) or to induce dsDNA buckling (around +20 pN nm under similar force loads) (14), and thus, branch migration would be favored over either of these structural changes upon the introduction of torsional stress. They set a new scale for what may be considered to be experimentally accessible physiologically relevant torques and suggest a mechanism for dissipation of torsional stress on DNA via junction migration.

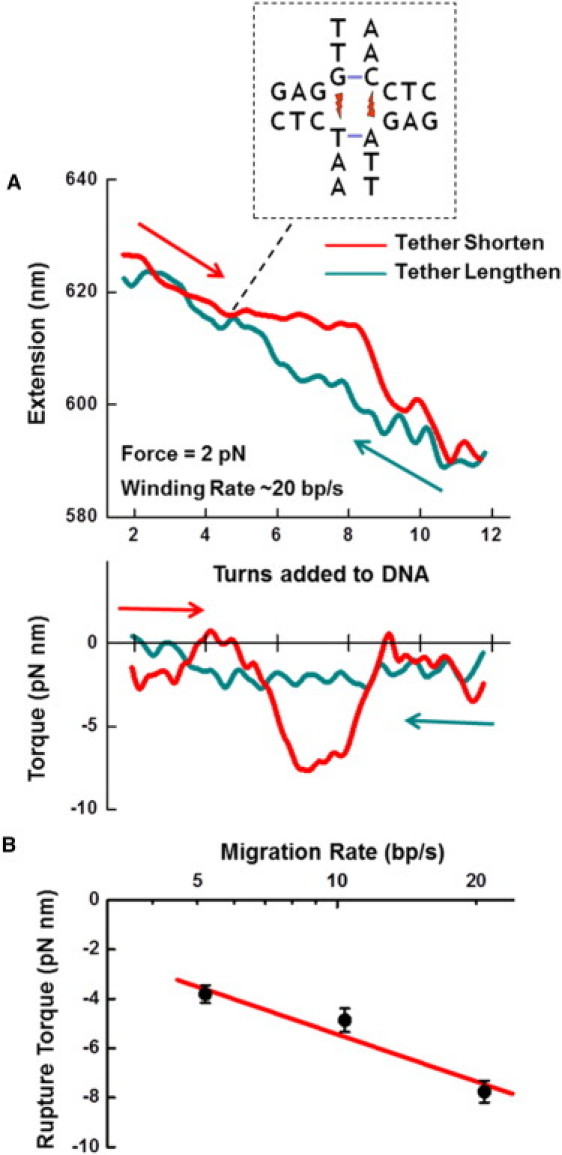

We next examined junction migration through heterologous basepairing. To determine the torsional barrier imposed by a sequence heterology, we mechanically migrated a junction containing a single-base heterology inserted into the construct at a predefined location (Fig. 2 A, and Fig. S1 and text in the Supporting Material). A junction was migrated at rates comparable to those generated by RuvAB (20) to simulate enzyme action. As shown, junction migration was indeed prevented by the heterologous base until enough torque had built up to create a set of mismatched bases in the side arms. This torque is much higher than the corresponding torque required to migrate a homologous junction and depended on the rate at which the torque increased during winding. In contrast, the reverse process showed no such impediment, as the mismatches located in the side arms were rapidly restored to a properly basepaired state in the vertical arms upon positive winding. Thus, the migration through a single base heterology under these conditions was a nonequilibrium process, and the torque depended on the migration rate when approaching the heterology (Fig. 2 B; Supporting Discussion). These results show that at the rate of migration by RuvAB (5–20 bp/s), a single base heterology in the Holliday junction can substantially increase the torque barrier by nearly an order of magnitude to ∼7 pN nm, which RuvAB or other junction-assisting enzymes would need to overcome during homologous recombination or homologous recombination-mediated DNA repair events.

Figure 2.

Migration through a single-base heterology. (A) Negative winding shortened the tether, but the heterology prevented smooth migration. Once sufficient torque was built up, the heterologous base was ruptured and migration continued. Upon reverse winding, the heterologous base was easily wound through, resulting in a return to full basepairing. (Inset) Schematic depicting the sequence content; location relative to the extension and torque data is noted. (B) Rupture torque measurements were taken while winding the tether at different rates.

Our study suggests that during recombination or double-stranded DNA break repair events, the migrating Holliday junction could act as a torque buffer that prevents the formation of torsionally generated DNA structures, such as plectonemes or melted DNA bubbles. Thus, Holliday junctions may be considered ultrasensitive nanotorque wrenches for stretches of homologous sequence. However, substantial torque can build up at a heterologous junction and must be overcome by enzymes like RuvAB, which utilize energy from the hydrolysis of ATP to bypass the sequence heterology and allow torsional relaxation.

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the Wang laboratory for critical reading of the manuscript and Drs. E. Alani and J. T. Lis for helpful scientific discussions.

M.D.W. acknowledges support from a National Science Foundation grant (MCB-0820293), a National Institutes of Health grant (R01 GM059849), the Keck Foundation, and the Cornell Nanobiotechnology Center.

Footnotes

Scott Forth's present address is Department of Chemistry and Cell Biology, The Rockefeller University, New York, NY 10065.

Christopher Deufel's present address is Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN 55905.

Supporting Material

References and Footnotes

- 1.Kowalczykowski S.C., Dixon D.A., Rehrauer W.M. Biochemistry of homologous recombination in Escherichia coli. Microbiol. Rev. 1994;58:401–465. doi: 10.1128/mr.58.3.401-465.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Gent D.C., Hoeijmakers J.H.J., Kanaar R. Chromosomal stability and the DNA double-stranded break connection. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2001;2:196–206. doi: 10.1038/35056049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ira G., Pellicioli A., Foiani M. DNA end resection, homologous recombination and DNA damage checkpoint activation require CDK1. Nature. 2004;431:1011–1017. doi: 10.1038/nature02964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Courcelle J., Hanawalt P.C. RecA-dependent recovery of arrested DNA replication forks. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2003;37:611–646. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.37.110801.142616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pearson C.E., Zorbas H., Zannis-Hadjopoulos M. Inverted repeats, stem-loops, and cruciforms: significance for initiation of DNA replication. J. Cell. Biochem. 1996;63:1–22. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4644(199610)63:1%3C1::AID-JCB1%3E3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.West S.C. Processing of recombination intermediates by the RuvABC proteins. Annu. Rev. Genet. 1997;31:213–244. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.31.1.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rasnik I., Jeong Y.J., Ha T. Branch migration enzyme as a Brownian ratchet. EMBO J. 2008;27:1727–1735. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Panyutin I.G., Hsieh P. The kinetics of spontaneous DNA branch migration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1994;91:2021–2025. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.6.2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Biswas I., Yamamoto A., Hsieh P. Branch migration through DNA sequence heterology. J. Mol. Biol. 1998;279:795–806. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.1769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dennis C., Fedorov A., Grigoriev M. RuvAB-directed branch migration of individual Holliday junctions is impeded by sequence heterology. EMBO J. 2004;23:2413–2422. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deufel C., Forth S., Wang M.D. Nanofabricated quartz cylinders for angular trapping: DNA supercoiling torque detection. Nat. Methods. 2007;4:223–225. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.La Porta A., Wang M.D. Optical torque wrench: angular trapping, rotation, and torque detection of quartz microparticles. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2004;92:190801. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.92.190801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Inman J., Forth S., Wang M.D. Passive torque wrench and angular position detection using a single-beam optical trap. Opt. Lett. 2010;35:2949–2951. doi: 10.1364/OL.35.002949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Forth S., Deufel C., Wang M.D. Abrupt buckling transition observed during the plectoneme formation of individual DNA molecules. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2008;100:148301. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.100.148301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sheinin M.Y., Wang M.D. Twist-stretch coupling and phase transition during DNA supercoiling. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2009;11:4800–4803. doi: 10.1039/b901646e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Panyutin I.G., Biswas I., Hsieh P. A pivotal role for the structure of the Holliday junction in DNA branch migration. EMBO J. 1995;14:1819–1826. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07170.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rafferty J.B., Sedelnikova S.E., Rice D.W. Crystal structure of DNA recombination protein RuvA and a model for its binding to the Holliday junction. Science. 1996;274:415–421. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5286.415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dawid A., Guillemot F., Heslot F. Mechanically controlled DNA extrusion from a palindromic sequence by single molecule micromanipulation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2006;96:188102. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.96.188102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Strick T.R., Bensimon D., Croquette V. Micro-mechanical measurement of the torsional modulus of DNA. Genetica. 1999;106:57–62. doi: 10.1023/a:1003772626927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dawid A., Croquette V., Heslot F. Single-molecule study of RuvAB-mediated Holliday-junction migration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:11611–11616. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404369101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.