Abstract

Plants produce volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in response to herbivore attack, and these VOCs can be used by parasitoids of the herbivore as host location cues. We investigated the behavioural responses of the parasitoid Cotesia vestalis to VOCs from a plant–herbivore complex consisting of cabbage plants (Brassica oleracea) and the parasitoids host caterpillar, Plutella xylostella. A Y-tube olfactometer was used to compare the parasitoids' responses to VOCs produced as a result of different levels of attack by the caterpillar and equivalent levels of mechanical damage. Headspace VOC production by these plant treatments was examined using gas chromatography–mass spectrometry. Cotesia vestalis were able to exploit quantitative and qualitative differences in volatile emissions, from the plant–herbivore complex, produced as a result of different numbers of herbivores feeding. Cotesia vestalis showed a preference for plants with more herbivores and herbivore damage, but did not distinguish between different levels of mechanical damage. Volatile profiles of plants with different levels of herbivores/herbivore damage could also be separated by canonical discriminant analyses. Analyses revealed a number of compounds whose emission increased significantly with herbivore load, and these VOCs may be particularly good indicators of herbivore number, as the parasitoid processes cues from its external environment.

Keywords: herbivore-induced plant volatiles, Hymenoptera, Lepidoptera, parasitoid host location, tritrophic, volatile organic compounds

1. Introduction

Vet & Dicke [1] hypothesized that parasitoids may experience a ‘reliability–detectability problem’ while locating their hosts and their hosts' habitats, whereby chemical cues released directly from their hosts are likely to be highly reliable and taxonomically specific, but, may have low detectability because natural selection has reduced host conspicuousness. They hypothesized that volatile organic compounds (VOCs) produced by plants provide alternate cues. Plant VOCs are produced in greater volume than host cues, and so are more detectable, but may be less reliable because they might convey information that is less taxonomically specific [1]. However, feeding by a herbivore can cause qualitative and quantitative changes in plant VOC emissions [2,3]. Considerable evidence shows that parasitoids exploit herbivore-induced plant VOCs in a wide variety of tritrophic systems consisting of many different plant, herbivore and parasitoid species (e.g. [2,4–10]).

Despite recent advances in understanding of the genetics and molecular biology of the production of herbivore-induced plant VOCs (e.g. [11–14]), little is known regarding host-density effects on VOC production, although host density significantly influences parasitoid foraging [15–17]. Parasitoids use their ability to differentiate between complex volatile blends to forage optimally for herbivore hosts [18]. Guerrieri et al. [19] demonstrated that broad-bean plants require a minimum infestation level of 40 Acyrthosiphon pisum aphids for at least 48–72 h to produce VOCs detectable to their parasitoid Aphidius ervi. If a parasitoid could use VOCs from the plant–herbivore complex to judge the density of a herbivore population on a plant, it could forage more efficiently, by concentrating its close-range search behaviour and allocating more foraging effort to patches with more herbivores.

Herbivore-induced plant VOCs are often extremely complex blends, differing in composition quantitatively and qualitatively between plant species [3] and qualitatively within a plant species, when it is attacked by different herbivore species [2,3,20,21]. Parasitoids show preferences for VOCs from plants infested with their host herbivore over a non-host herbivore [5], but not if both herbivore species are suitable hosts [22]. Plants produce different VOCs after attack by different instars of a herbivore, which are differentially attractive to parasitoids [9,20,23,24]. Herbivore-induced VOCs also change temporally in relation to damage [19,25].

The responses of parasitoids and other natural enemies to VOCs are unlikely to be determined by individual compounds in the VOC profiles but more likely by a combination of compounds and their ratios in the VOC blend [26–28]. The use of multivariate analyses for the examination of VOC profiles has recently increased [29–33] because they allow analysis of the VOC profile as a whole, and this form of integrated analysis more closely resembles information processing in insects. Van Dam & Poppy [34] proposed that multivariate analysis techniques be applied more innovatively to help interpret changes in patterns of VOC blends.

We investigated whether a plant–herbivore complex emits different headspace VOC blends as a result of different degrees of herbivore infestation as well as equivalent mechanical damage, and, whether parasitoids respond behaviourally to any of these differences. We used a tritrophic system consisting of cabbage plants (Brassica oleracea), the diamondback moth Plutella xylostella and its specialist parasitoid Cotesia vestalis (formerly known as plutellae), which responds to plant VOCs produced resulting from P. xylostella infestation [8].

2. Material and methods

(a). Plants

Brassica oleracea var. capitata cv. Derby day seeds (Tozer Seeds, Surrey, UK) were sown in John Innes no. 2 compost (Minster Brand Products, Dorchester, UK) in a greenhouse with a minimum day-time temperature of 20°C (16 h) and a minimum night-time temperature of 14°C (8 h). Overhead lighting (mercury halide and sodium bulbs) was provided during the day to ensure a minimum light intensity of 300 W m−2. Seedlings were transplanted after two weeks into individual 13 cm plastic plant pots and grown for another four weeks.

(b). Insects

Colonies of both P. xylostella and C. vestalis were established from long-term UK laboratory strains kept by Rothamsted Research, and reared on six-week-old Chinese cabbage (Brassica rapa L. ssp. pekinensis (Lour.) var. Wong Bok) (Kings Seeds, Surrey, UK) grown in John Innes no. 2 compost. Both colonies were kept in 1 × 1 m Perspex cages in controlled temperature rooms, at 20 ± 2°C under a 16 L : 8 D light regime. Cotesia vestalis pupae were continuously collected from host–parasitoid cultures and isolated in empty cages. When they emerged, they were allowed to mate and were provided with a 10 per cent honey solution as a food source. All parasitoids used in experiments were naive, excluding the conditioning they receive upon emergence, to ensure that their responses to the different VOC profiles were innate and not altered by habituation to an alternate profile [35].

(c). Olfactometry

A glass Y-tube olfactometer (e.g. [5]) was used to record behavioural responses of C. vestalis to pairs of different volatile sources. The olfactometer had an internal diameter of 2 cm, an 18 cm stem and 16 cm arms at a 60° angle. Air was pumped through Teflon tubing, purified by passage through activated charcoal and humidified by bubbling through distilled water. Airflow was divided by a brass T-junction (Swagelok, OH, USA) and then passed through two separate flow meters, which regulated the flow rate to 0.6 l min−1. The air passed through two Plexiglas chambers (500 mm high × 300 mm diameter), containing the volatile sources to be tested, and into the arms of the olfactometer. All tests were performed in a constant-temperature room at 23 ± 2°C. Visual cues were excluded by placing a white cardboard screen around the Y-tube. The Y-tube was lit from above by two 15 W fluorescent lamps, producing a light intensity of 1.7 klx and fitted with a prismatic filter to ensure an even distribution of light. Both parasitoids and volatile sources were placed under the lamp at least 1 h before any experiments were conducted to allow them to acclimatize to light and temperature levels. Individual naive female C. vestalis that were 2–5 days old were introduced to the Y-tube and given 5 min to make a choice. When a parasitoid moved 8 cm up an arm of the olfactometer, it was defined as having selected an odour. The position of the treatments was swapped between the arms of the Y-tube every five replicates. Between trials, all glassware was washed in Decon90, rinsed with acetone and distilled water and then baked at 200°C for 3–4 h to remove any volatile chemicals adhering to the glass. Airflow was continuously maintained through the apparatus and tubing when not conducting an experiment.

(d). Dual-choice experiments

Two experiments were conducted. In the first, B. oleracea plants were either undamaged or infested with 5, 10 or 20 third-instar P. xylostella larvae for 72 h prior to the trial. To investigate whether C. vestalis responds differently to different levels of P. xylostella damage, the responses of female C. vestalis were tested to each of following pairs of B. oleracea treatments: (i) undamaged versus infested with five larvae, (ii) infested with five larvae versus infested with 10 larvae, and (iii) infested with 10 larvae versus infested with 20 larvae. After testing, the plants were photographed and the leaf area and the area consumed by P. xylostella calculated using ImageJ (v. 1.37 National Institutes of Health: [36]).

In the second experiment, plants used were either undamaged or mechanically damaged with a total of 10, 20 or 40 holes, using a hole punch cumulatively, once a day, over 3 days. The final damage was done a minimum of 2 h before the start of bioassays (ca 11.00). One hole produced 0.29 cm2 of damage, and the total number of holes punched removed an equivalent area of the leaf that would have been removed by 5, 10 and 20 P. xylostella outlined in the first experiment above. To investigate whether C. vestalis responds differently to different levels of mechanical damage, the responses of naive female C. vestalis were tested to each of following pairs of B. oleracea treatments: (i) undamaged versus damaged with 10 holes, (ii) damaged with 10 holes versus damaged with 20 holes, and (iii) damaged with 20 holes versus damaged with 40 holes.

The six different dual-choice experiments were conducted over a 5 day period; on each of the 5 days, separate replicates for every dual-choice experiment were conducted. On each day for each dual choice, the responses of 10 different naive C. vestalis to a pair of plants were tested; different plants were used every day and each C. vestalis was only ever used once. Therefore, for each dual-choice experiment, the responses of a total of 50 individuals were tested to a total of five plants of each treatment, as is standard for these types of experiments (e.g. [2,37]).

(e). Headspace volatile entrainments

Volatile entrainments were collected for both mechanically damaged and P. xylostella-infested B. oleracea plants. In the first experiment, plants were either undamaged or infested with 5, 10 or 20 third-instar P. xylostella larvae for 72 h prior to the trial. Insects were left on the plants during volatile collections. In the second experiment, plants were either undamaged or damaged with 10, 20 or 40 holes, as in the dual-choice experiments above. Entrainments were completed using a method similar to that described by Stewart-Jones & Poppy [38]. Plants were enclosed in a poly(ethylene terephthalate) (PET) tube (22 cm diameter, 60 cm length, 25 µm thickness; Kalle UK Ltd, Witham, UK), which had previously been purged overnight by purified air (0.9 l min−1; activated charcoal, BDH, 10–14 mesh, 50 g). The top of the plant pots was wrapped in three pieces of aluminium sheet to isolate soil from vegetative parts, but the roots remained aerated. The PET tube enclosed the whole plant and was fixed to the rim of the pot using a loop of wire and was closed loosely at the top also with some wire. Air was filtered through activated charcoal and blown in (0.9 l min−1) near the base of the plant and drawn out at the top through a Tenax TA trap (0.6 l min−1). This created a positive pressure within the bag, which ensured unfiltered air did not enter. Plants were enclosed between 10.00 and 11.00 and before sampling was started the system was purged for 30 min by blowing air in only. VOCs were collected on Tenax TA (50 mg, mesh 60–80, Supelco, Bellefonte, PA, USA) held in thermal desorption sampling tubes (Anatune Optic PTV liner, Cambridgeshire, UK) by plugs of silanized wool. Tenax TA filters were first washed thoroughly with redistilled diethyl ether (5 ml) and baked under a slow flow of purified nitrogen (225°C, 2 h). All entrainments were carried out between 11.00 and 15.30, and each entrainment lasted 4 h, after which liners were sealed in glass tubes and stored in the freezer (−22°C) until analysis. After sampling, the plants were cut, photographed and the leaf area calculated. There were no significant differences between total leaf areas across treatments (ANOVA, F3,16 = 0.64, p = 0.599).

(f). Coupled gas chromatography–mass spectrometry

Samples were thermally desorbed using an Optic 2 programmable injector (Anatune, Cambridgeshire, UK) fitted to an Agilent 6890 GC coupled to a Hewlett-Packard 5972 Quadrupole Mass Selective Detector that ionized by electron ionization (−70 eV). VOCs collected and trapped on the Tenax TA were released directly onto the column by thermal desorption. The whole liner was inserted into the inlet. Injector conditions were equilibrated (30 s) and then ramped from 30°C to 220°C at 16°C s−1, the carrier gas was helium (8 psi constant) and the injector was operated in a split mode (1 : 2) for rapid transfer of analytes to the column. The capillary column was a BPX5MS (SGE, Australia; 30 m × 0.25 mm i.d., 0.5 µm film), and oven temperature was held at 30°C for 2 min, then programmed at 4°C min−1 to 200°C, then 10°C min−1 to 250°C and held for 10 min. The mass spectrometer (172°C) scanned from mass 330 to 33 at a rate of 2.5 times s−1 and data were captured and analysed by Enhanced ChemStation software (v. B.01.00). VOCs were initially tentatively identified by comparing spectra with those in Wiley 275 and Nist 98 analytical databases and our own database, and their peak areas recorded. Confirmation was achieved for a number of the VOCs by comparison of spectra and retention times with those of authenticated standards. For some of the compounds for which standards were unavailable, tentative identifications were determined from Kovat's indices and database matches. To avoid coelution problems and improve limits of detection, total ion current was not quantified. A target ion was quantified for each compound and validated using two qualifier ions for which a relative response was determined.

(g). Statistical analyses

Behavioural preferences of C. vestalis in dual-choice tests were analysed using generalized linear mixed models (GLMM) for both the P. xylostella and the mechanical damage experiments. Each GLMM used a Poisson distribution and logit link function. Within an experiment, replicates for all three dual-choice tests were conducted over a number of days; for each replicate, the preference of 10 wasps was determined to a fresh pair of plants on the same day. The total preferences of 10 wasps per plant pair were used as the replicate to avoid pseudoreplication in GLMM analyses, rather than the responses of individual wasps. Plant pair was nested within dual-choice test type as a random effect. To assess whether parasitoids displayed a significant preference between plant treatments in each dual-choice test, the mean logit for each dual-choice test type was compared with zero. In addition, comparisons were made to investigate whether parasitoid preferences changed between dual-choice tests. GLMM tests were conducted using R (v. 2.11.1).

Air entrainment data were analysed to test for differences in VOC emissions between plant treatments. To compare the differences in recorded peak areas between plant treatments for each individual VOC, peak areas were first tested for univariate normality. A series of Shapiro–Wilk tests and residual plots demonstrated that peak areas and their residuals were non-normal and could not be normalized by transformation for a number of VOCs. Therefore, a series of randomized ANOVAs were conducted, using Resampling Procedures software (v. 1.3), to investigate whether the distribution of observed peak areas to each treatment was significantly different from that expected from a random assignment. For each randomized ANOVA the data were randomized 10 000 times.

Canonical discriminant analysis (CDA) by the forward stepwise method was completed on the peak areas of the different VOCs for both entrainment experiments. CDA allows for the identification of those VOCs that discriminate most clearly between treatments. For both experiments, emissions of VOCs varied qualitatively between plants, meaning that for many of the VOCs, only a few observations were recorded. In addition, some VOCs only contributed a very minor proportion to total emissions. Therefore, to focus analyses on VOCs that contributed a consistent and substantial proportion to VOC emissions, only those VOCs whose peak area contributed more than 0.5 per cent of the total peak area of all VOCs were included in CDAs; Degen et al. [30] used a similar cut-off point. Consequently, for the P. xylostella and mechanical damage experiments, 29 and 22 VOCs, respectively, were selected for inclusion in each CDA. This method avoids the inclusion of VOCs based upon a priori biases resulting from previous research and instead bases selection purely on their contribution to the overall profile. Omnibus tests for multivariate normality on these data demonstrated that they were not normally distributed. Therefore, a randomization CDA test was conducted for each experiment, in which observed peak areas for each VOC were randomly assigned to treatments and the χ2 statistic for all canonical functions calculated. This procedure was repeated 1000 times. p-values were calculated as the proportion of randomized χ2 statistics equal to or greater than the observed χ2. CDAs were conducted using SPSS (v. 15.0).

3. Results

(a). Olfactometry

In all experiments conducted, 99 per cent of C. vestalis chose between odour sources, indicating that the volatile sources were very attractive. Overall, naive female C. vestalis significantly preferred cabbage plants infested with more hosts (Wald Z2,6 = 5.049, p < 0.001). In dual-choice tests, 64 per cent of 50 females preferred plants infested with five larvae for 3 days over undamaged plants. Furthermore, 70 per cent of females significantly preferred plants infested with 10 larvae over those infested with five larvae and 80 per cent preferred plants infested with 20 larvae over 10 larvae. Although these results suggest that increasing P. xylostella infestation may enhance the attractiveness of cabbage, this increase was not quite significant (Wald Z2,6 = 1.762, p = 0.078). In the comparative experiments, naive female C. vestalis exhibited no preference based on the severity of mechanical damage (Wald Z2,6 = 0.164, p = 0.87).

(b). Headspace volatile entrainments

Qualitative differences in VOC emissions occurred between undamaged and P. xylostella-infested plants; infested plants produced 125 different VOCs, 16 more than undamaged control plants. Plants infested with five larvae emitted 120 VOCs, those with 10 and 20 larvae both emitted 125 VOCs. Randomized ANOVAs indicated that the distribution of observed peak areas to each plant treatment was significantly different from random for 44 VOCs; in all cases, emissions increased after infestation. Twelve of these compounds were significantly different from random at p < 0.001, 18 at p < 0.01 and 14 at p < 0.05. The four most significant compounds were dimethyl trisulphide, 3-methyl-2-pentanol (tentative ID) indole and methyl salicylate (table 1). Of these 44 VOCs, 34 were released by both undamaged and infested plants, demonstrating quantitative differences in emission rates between treatments.

Table 1.

Volatile compounds collected from the headspace of B. oleracea plants either undamaged or infested with 5, 10 or 20 P. xylostella larvae for 72 h prior to volatile collection. (Data are expressed as the mean peak areas (×1000) of five plants for each treatment ± s.e. U followed by a number represents an unidentified compound. Fobs are F-values observed from one-way ANOVAs. p-values were calculated as the proportion of F-values (obtained from 10 000 ANOVAs conducted on randomizations of the data) greater than Fobs; only those compounds significant at p < 0.01 are shown (for all other significant VOCs, see electronic supplementary material, table S1).)

| volatile compound | number of larvae on plant |

Fobs | proportion of randomized F > Fobs | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 5 | 10 | 20 | |||

| dimethyl trisulphide | 49 ± 20 | 188 ± 30 | 290 ± 38 | 857 ± 39 | 117.099 | <0.001 |

| 3-methyl-2-pentanola | 70 ± 12 | 184 ± 41 | 294 ± 46 | 662 ± 98 | 19.383 | <0.001 |

| indole | 81 ± 29 | 602 ± 201 | 574 ± 153 | 1509 ± 142 | 16.714 | <0.001 |

| methyl salicylate | 27 ± 14 | 203 ± 41 | 129 ± 35 | 465 ± 74 | 16.408 | <0.001 |

| U1 | 0 ± 0 | 8 ± 8 | 20 ± 14 | 157 ± 34 | 15.499 | <0.001 |

| U2 | 0 ± 0 | 19 ± 12 | 50 ± 20 | 129 ± 19 | 14.921 | <0.001 |

| U3 | 0 ± 0 | 0 ± 0 | 1 ± 1 | 13 ± 3 | 13.151 | <0.001 |

| U4 | 0 ± 0 | 7 ± 4 | 18 ± 7 | 46 ± 8 | 13.003 | <0.001 |

| U5 | 1 ± 1 | 16 ± 11 | 29 ± 8 | 205 ± 53 | 12.125 | <0.001 |

| dimethyl disulphide | 33 ± 17 | 89 ± 8 | 112 ± 17 | 312 ± 73 | 9.875 | <0.001 |

| 3-methyl-2-pentanonea | 5 ± 3 | 13 ± 2 | 24 ± 5 | 45 ± 10 | 9.396 | <0.001 |

| β-cubebenea | 4 ± 2 | 66 ± 21 | 93 ± 31 | 271 ± 77 | 7.098 | <0.001 |

| U6 | 1 ± 1 | 22 ± 9 | 37 ± 8 | 73 ± 12 | 11.894 | 0.001 |

| U7 | 0 ± 0 | 0 ± 0 | 1 ± 1 | 8 ± 2 | 9.254 | 0.001 |

| U8 | 0 ± 0 | 2 ± 2 | 1 ± 1 | 25 ± 8 | 9.103 | 0.001 |

| eugenola | 0 ± 0 | 17 ± 8 | 24 ± 5 | 141 ± 39 | 10.427 | 0.002 |

| methyl isothiocyanatea | 9 ± 5 | 28 ± 5 | 31 ± 4 | 73 ± 16 | 9.138 | 0.002 |

| (E)-10-heneicosenea | 1 ± 1 | 2 ± 1 | 8 ± 2 | 13 ± 3 | 7.372 | 0.002 |

| benzyl nitrilea | 159 ± 42 | 616 ± 160 | 1465 ± 345 | 2590 ± 735 | 6.652 | 0.003 |

| C20 hydrocarbona | 0 ± 0 | 1 ± 1 | 6 ± 2 | 11 ± 3 | 8.341 | 0.004 |

| 2-ethyl-3-methyl-maleimidea | 26 ± 5 | 104 ± 32 | 89±24 | 180 ± 24 | 7.195 | 0.004 |

| (Z)-2-penten-1-ol, acetatea | 44 ± 14 | 137 ± 46 | 202 ± 28 | 323 ± 75 | 6.374 | 0.004 |

| U9 | 21 ± 3 | 81 ± 24 | 84 ± 17 | 440 ± 236 | 2.593 | 0.004 |

| α,α-dimethyl-benzene ethanola | 1 ± 1 | 2 ± 1 | 5 ± 3 | 30 ± 10 | 6.551 | 0.005 |

| U10 | 2 ± 1 | 25 ± 11 | 22 ± 6 | 61 ± 16 | 5.776 | 0.007 |

| β-phenyl butyratea | 2 ± 2 | 48 ± 18 | 57 ± 16 | 212 ± 75 | 5.433 | 0.007 |

| U11 | 0 ± 0 | 2 ± 1 | 11 ± 4 | 37 ± 15 | 4.609 | 0.007 |

| U12 | 4 ± 4 | 23 ± 9 | 29 ± 7 | 64 ± 20 | 4.51 | 0.008 |

| amyl acetatea | 2 ± 1 | 7 ± 3 | 8 ± 1 | 26 ± 9 | 4.667 | 0.009 |

| U13 | 16 ± 6 | 15 ± 3 | 14 ± 2 | 54 ± 18 | 4.176 | 0.009 |

aTentative identifications.

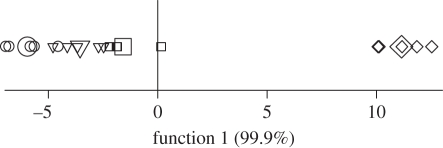

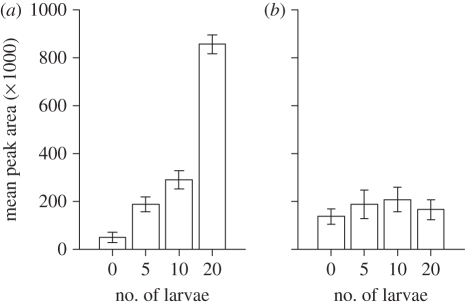

The randomized CDA for P. xylostella-infested plants demonstrated that the discrimination ability of the canonical functions, for the observed data, was significantly different from functions obtained when peak areas were randomly assigned to treatments (p = 0.012). The first canonical function explained 99.9 per cent of the variance and the second only 0.1 per cent (figure 1). There was good separation on the first axis between plant treatments, with width of separation increasing at higher infestation levels, and group means differed significantly (Wilks' λ2,16 = 0.02, p < 0.001). Two chemicals were included in the stepwise classification of VOCs; dimethyl trisulphide and 6-methyl-5-hepten-2-ol (tentative ID; figure 2).

Figure 1.

The first canonical discriminant function used to classify volatiles collected from the headspace of B. oleracea plants undamaged (circles) or infested with 5 (triangles), 10 (squares) or 20 (diamonds) P. xylostella larvae for 72 h prior to volatile collection (n = 5). Large symbols indicate the discriminant function of the group centroid for each treatment and smaller symbols indicate the functions for each data point within that particular treatment.

Figure 2.

Mean peak areas (±s.e.) of (a) dimethyl trisulphide, and (b) 6-methyl-5-hepten-2-ol (tentative ID), identified from the headspace of B. oleracea plants either undamaged or infested with 5, 10 or 20 P. xylostella larvae for 72 h prior to volatile collection.

By contrast, mechanically damaged plants showed few differences between treatments. These plant treatments emitted 106 different VOCs, with 94, 93 and 96 VOCs emitted from plants with 10, 20 or 40 holes, respectively. Undamaged control plants emitted 100 VOCs. Few qualitative differences in VOC profiles occurred, with only five VOCs extra being emitted by at least one of the mechanical damage treatments, but not the undamaged controls. Randomized ANOVAs indicated that the distribution of observed peak areas to each plant treatment was significantly different from random for only five VOCs (electronic supplementary material, table S2). Only benzyl nitrile (tentative ID) emissions increased with damage. The randomized CDA for mechanically damaged plants showed that the discrimination ability of the canonical functions was not different from functions obtained from a random assignment of peak areas to treatments (p = 0.396).

4. Discussion

To identify a suitable host patch, a parasitoid requires unambiguous and reliable cues that indicate the location, quality and density of its host. It is well established that VOCs produced from a plant–herbivore complex provide both reliable and detectable cues that parasitoids can use to locate their herbivore hosts [2,5,7,10]. Parasitoids can use these herbivore-induced VOCs when in a patch, to assess its profitability and adapt their patch residence time, in order to forage more optimally [18]. Parasitoids are unable, at a distance, to visually assess the density of host herbivores on a plant and require other forms of information. Our findings, that naive C. vestalis significantly prefers VOCs from B. oleracea plants infested with more P. xylostella in a density-dependant fashion, provide evidence that a parasitoid is capable of responding innately to VOC cues from a plant–herbivore complex to distinguish between plants of the same species with different levels of herbivore infestation/damage. These experiments used walking assays, which may produce different responses to flying assays; therefore, caution must be taken in extrapolating the conclusions of this study to insects locating patches in-flight.

The results of the VOC analyses complemented these behavioural data, with qualitative increases and greater differences in emissions between plant treatments as herbivore loads rose. As figure 2 illustrates, emission of some VOCs exhibits an accelerating positive relation with herbivore density. If parasitoids perceive VOCs in proportion to their concentration, they should therefore exhibit a stronger preference for plants with more larvae when confronted with 20 versus 10 larvae than with 10 versus 5 larvae, which in turn should elicit a stronger preference than a comparison between 5 versus 0 larvae. This increasing preference appears apparent from the behavioural data but was not quite statistically significant.

The fact that parasitoids preferentially select plants infested with more herbivores could have implications for how they regulate host populations and therefore their effectiveness as biocontrol agents. An ideal biocontrol agent suppresses a pest population but does not eliminate it [39]. When foraging in an agricultural monoculture, where there are likely to be only short distances between hosts, a parasitoid that selects plants producing a strong signal, and therefore with more hosts, should reduce the likelihood that it will eliminate a host population but may still suppress outbreaks. The responses here are from naive parasitoids, suggesting that they are innate and that parasitoids may prefer a volatile source based on the strength of a signal without prior experience of how volatile emissions relate to herbivore density. Therefore, assuming that the response is owing to an overall increase in certain VOCs and not how their relative concentrations vary within the blend, a foraging parasitoid may prefer the strongest signal whether that is the result of low damage on a plant spatially close or high damage on one further away. In this scenario, it may be advantageous for a plant to produce as strong a signal as possible. Shiojiri et al. [40] recently proposed the concept of ‘cry wolf’ signalling, where plants ‘dishonestly’ produce strong VOC emissions in the presence of only minor damage. They demonstrated that C. vestalis were unable to distinguish between different damage levels on B. oleracea var. capitata cv. Shikidori, but did show density-dependent responses on B. oleracea var. acephala. They also demonstrate that both plants signal ‘honestly’ in response to attack by the cabbage white larvae, Pieris rapae. Our data suggest that B. oleracea var. capitata cv. Derby day infested with P. xylostella produce ‘honest’ signals, which may be more common than ‘dishonest’ signals.

An ability to use VOCs from the plant–herbivore complex to locate more profitable patches may not be restricted to parasitoids; Gols et al. [41] demonstrated that a predatory mite responds with increasing strength to plants infested with increasing numbers of its spider mite prey. Horiuchi et al. [42] found that plants with higher infestations of spider mites produced greater emissions of certain volatiles and to a limited extent, these differences correlated with the plants' attractiveness to a predator of the mite. However, only 10 VOCs were analysed, based on a priori knowledge of this system from previous investigation, half of which did not increase as a result of infestation.

Van Dam & Poppy [34] highlighted that current methodologies often struggle to identify causal links between an insects' behaviour and the exact VOCs that actually elicit that behaviour. Currently, this issue is only addressed by the use of coupled gas chromatography–electroantennography (e.g. [43]) and neurophysiology techniques (e.g. [44,45]) to identify those volatiles to which the insect is physiologically responsive. However, this does not always translate to behavioural responsiveness. Here, we demonstrate that by using CDA and ANOVAs, it is possible to identify those VOCs that vary positively with herbivore density and which could therefore be reliable indicators of increasing herbivore numbers, assuming that parasitoid sensitivity increases linearly with concentration and equally among VOCs.

In the current analyses, the VOCs that these analyses intimated could be key compounds included dimethyl trisulphide, methyl salicylate, indole and dimethyl disulphide. The next step would be to investigate the behavioural responsiveness of C. vestalis to these VOCs, to confirm their suitability as VOCs that may be used to gauge herbivore number on a plant. However, it has already been shown that C. vestalis responds significantly to dimethyl trisulphide in Y-tube olfactometry tests [46], and both indole and methyl salicylate are attractive to other closely related Cotesia spp. [47,48]. Dimethyl disulphide and dimethyl trisulphide are given off by frass of P. xylostella [49] and were emitted in significantly greater quantities from plants infested with higher herbivore numbers (table 1). These two compounds may have been derived from frass still on the plant, as would be found in real foraging situations, rather than from the plants themselves. Whatever their derivation, their presence and concentration may still be good indicators of herbivore presence and load. As a result of natural selection, parasitoids are likely to weight the importance of certain compounds during neural processing based on their reliability, and, therefore, these analyses could be used as a powerful technique to identify such putative key compounds in parasitoid host location.

Behavioural and chemical analyses did not distinguish between plant treatments in the mechanical damage experiment (figure 2). By contrast, C. vestalis has previously been shown to prefer VOCs from plants with similar mechanical damage over undamaged plants [8]. Different methods of administering mechanical damage result in different VOC emissions and chemical elicitors present in herbivores saliva also alter plant VOC emissions. Controversy exists in the literature as to how best mimic caterpillar damage [29,50–53].

Insect parasitoids that exploit insect herbivores as hosts comprise a vast and varied group, which employ a huge range of different foraging strategies based upon their life-history characteristics. Many of these parasitoid species are able to use VOCs from the plant–herbivore complex to increase their host foraging efficiency. If, as our findings suggest, a parasitoid can further increase its patch-finding ability by using VOC emissions to select more rewarding host patches, then this strategy has the potential to be pervasive among other species of insect parasitoids that possess similar life histories.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr Simon Leather for his comments on the research and Prof. Lawrence Harder for his advice on statistical analyses. Funding was provided by BBSRC grant BB/D01154x/1.

References

- 1.Vet L. E. M., Dicke M. 1992. Ecology of infochemical use by natural enemies in a tritrophic context. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 37, 141–172 10.1146/annurev.en.37.010192.001041 (doi:10.1146/annurev.en.37.010192.001041) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Du Y. J., Poppy G. M., Powell W., Pickett J. A., Wadhams L. J., Woodcock C. M. 1998. Identification of semiochemicals released during aphid feeding that attract parasitoid Aphidius ervi. J. Chem. Ecol. 24, 1355–1368 10.1023/A:1021278816970 (doi:10.1023/A:1021278816970) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Turlings T. C. J., Wackers F. L., Vet L. E. M., Lewis W. J., Tumlinson J. H. 1993. Learning of host-finding cues by hymenopterous parasitoids. In Insect learning: ecological and evolutionary perspectives (eds Papaj D. R., Lewis A. C.), pp. 51–78 London, UK: Chapman and Hall, Inc [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dicke M., Vanbeek T. A., Posthumus M. A., Bendom N., Vanbokhoven H., Degroot A. E. 1990. Isolation and identification of volatile kairomone that affects acarine predator–prey interactions: involvement of host plant in its production. J. Chem. Ecol. 16, 381–396 10.1007/BF01021772 (doi:10.1007/BF01021772) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Du Y. J., Poppy G. M., Powell W. 1996. Relative importance of semiochemicals from first and second trophic levels in host foraging behavior of Aphidius ervi. J. Chem. Ecol. 22, 1591–1605 10.1007/BF02272400 (doi:10.1007/BF02272400) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Girling R. D., Hassall M., Turner J. G., Poppy G. M. 2006. Behavioural responses of the aphid parasitoid Diaeretiella rapae to volatiles from Arabidopsis thaliana induced by Myzus persicae. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 120, 1–9 10.1111/j.1570-7458.2006.00423.x (doi:10.1111/j.1570-7458.2006.00423.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Paré P. W., Tumlinson J. H. 1997. Induced synthesis of plant volatiles. Nature 385, 30–31 10.1038/385030a0 (doi:10.1038/385030a0) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Potting R. P. J., Poppy G. M., Schuler T. H. 1999. The role of volatiles from cruciferous plants and pre-flight experience in the foraging behaviour of the specialist parasitoid Cotesia plutellae. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 93, 87–95 10.1023/A:1003822208843 (doi:10.1023/A:1003822208843) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Takabayashi J., Sato Y., Horikoshi M., Yamaoka R., Yano S., Ohsaki N., Dicke M. 1998. Plant effects on parasitoid foraging: differences between two tritrophic systems. Biol. Cont. 11, 97–103 10.1006/bcon.1997.0583 (doi:10.1006/bcon.1997.0583) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Turlings T. C. J., Mccall P. J., Alborn H. T., Tumlinson J. H. 1993. An elicitor in caterpillar oral secretions that induces corn seedlings to emit chemical signals attractive to parasitic wasps. J. Chem. Ecol. 19, 411–425 10.1007/BF00994314 (doi:10.1007/BF00994314) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arimura G., Matsui K., Takabayashi J. 2009. Chemical and molecular ecology of herbivore-induced plant volatiles: proximate factors and their ultimate functions. Plant. Cell Physiol. 50, 911–923 10.1093/pcp/pcp030 (doi:10.1093/pcp/pcp030) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Girling R. D., Madison R., Hassall M., Poppy G. M., Turner J. G. 2008. Investigations into plant biochemical wound-response pathways involved in the production of aphid-induced plant volatiles. J. Exp. Bot. 59, 3077–3085 10.1093/Jxb/Ern163 (doi:10.1093/Jxb/Ern163) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pieterse C. M. J., Dicke M. 2007. Plant interactions with microbes insects: from molecular mechanisms to ecology. Trends Plant Sci. 12, 564–569 10.1016/j.tplants.2007.09.004 (doi:10.1016/j.tplants.2007.09.004) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Snoeren T., Van Poecke R., Dicke M. 2009. Multidisciplinary approach to unravelling the relative contribution of different oxylipins in indirect defense of Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Chem. Ecol. 35, 1021–1031 10.1007/s10886-009-9696-3 (doi:10.1007/s10886-009-9696-3) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hassell M. P. 2000. Host–parasitoid population dynamics. J. Anim. Ecol. 69, 543–566 10.1046/j.1365-2656.2000.00445.x (doi:10.1046/j.1365-2656.2000.00445.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Van Baalen M., Sabelis M. W. 1993. Coevolution of patch selection strategies of predator and prey and the consequences for ecological stability. Am. Nat. 142, 646–670 10.1086/285562 (doi:10.1086/285562) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Van Baalen M., Sabelis M. W. 1999. Non-equilibrium population dynamics of ‘ideal and free’ prey and predators. Am. Nat. 154, 69–88 10.1086/303215 (doi:10.1086/303215) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tentelier C., Fauvergue X. 2007. Herbivore-induced plant volatiles as cues for habitat assessment by a foraging parasitoid. J. Anim. Ecol. 76, 1–8 10.1111/j.1365-2656.2006.01171.x (doi:10.1111/j.1365-2656.2006.01171.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guerrieri E., Poppy G. M., Powell W., Tremblay E., Pennacchio F. 1999. Induction and systemic release of herbivore-induced plant volatiles mediating in-flight orientation of Aphidius ervi. J. Chem. Ecol. 25, 1247–1261 10.1023/A:1020914506782 (doi:10.1023/A:1020914506782) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.De Moraes C. M., Lewis W. J., Pare P. W., Alborn H. T., Tumlinson J. H. 1998. Herbivore-infested plants selectively attract parasitoids. Nature 393, 570–573 10.1038/31219 (doi:10.1038/31219) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Powell W., Pennacchio F., Poppy G. M., Tremblay E. 1998. Strategies involved in the location of hosts by the parasitoid Aphidius ervi Haliday (Hymenoptera: Braconidae: Aphidiinae). Biol. Cont. 11, 104–112 10.1006/bcon.1997.0584 (doi:10.1006/bcon.1997.0584) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blande J. D., Pickett J. A., Poppy G. M. 2007. A comparison of semiochemically mediated interactions involving specialist and generalist Brassica-feeding aphids and the braconid parasitoid Diaeretiella rapae. J. Chem. Ecol. 33, 767–779 10.1007/s10886-007-9264-7 (doi:10.1007/s10886-007-9264-7) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gouinguené S., Alborn H., Turlings T. C. J. 2003. Induction of volatile emissions in maize by different larval instars of Spodoptera littoralis. J. Chem. Ecol. 29, 145–162 10.1023/A:1021984715420 (doi:10.1023/A:1021984715420) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Takabayashi J., Takahashi S., Dicke M., Posthumus M. A. 1995. Developmental stage of herbivore Pseudaletia separata affects production of herbivore-induced synomone by corn plants. J. Chem. Ecol. 21, 273–287 10.1007/BF02036717 (doi:10.1007/BF02036717) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hoballah M. E., Turlings T. C. J. 2005. The role of fresh versus old leaf damage in the attraction of parasitic wasps to herbivore-induced maize volatiles. J. Chem. Ecol. 31, 2003–2018 10.1007/s10886-005-6074-7 (doi:10.1007/s10886-005-6074-7) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bruce T. J. A., Wadhams L. J., Woodcock C. M. 2005. Insect host location: a volatile situation. Trends Plant Sci. 10, 269–274 10.1016/j.tplants.2005.04.003 (doi:10.1016/j.tplants.2005.04.003) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.De Boer J. G., Posthumus M. A., Dicke M. 2004. Identification of volatiles that are used in discrimination between plants infested with prey or nonprey herbivores by a predatory mite. J. Chem. Ecol. 30, 2215–2230 10.1023/B:JOEC.0000048784.79031.5e (doi:10.1023/B:JOEC.0000048784.79031.5e) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meiners T., Wackers F., Lewis W. J. 2003. Associative learning of complex odours in parasitoid host location. Chem. Senses 28, 231–236 10.1093/chemse/28.3.231 (doi:10.1093/chemse/28.3.231) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Connor E. C., Rott A. S., Samietz J., Dorn S. 2007. The role of the plant in attracting parasitoids: response to progressive mechanical wounding. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 125, 145–155 10.1111/j.1570-7458.2007.00602.x (doi:10.1111/j.1570-7458.2007.00602.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Degen T., Dillmann C., Marion-Poll F., Turlings T. C. J. 2004. High genetic variability of herbivore-induced volatile emission within a broad range of maize inbred lines. Plant Physiol. 135, 1928–1938 10.1104/pp.104.039891 (doi:10.1104/pp.104.039891) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ozawa R., Arimura G., Takabayashi J., Shimoda T., Nishioka T. 2000. Involvement of jasmonate- and salicylate-related signaling pathways for the production of specific herbivore-induced volatiles in plants. Plant. Cell Physiol. 41, 391–398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pareja M., Mohib A., Birkett M. A., Dufour S., Glinwood R. T. 2009. Multivariate statistics coupled to generalized linear models reveal complex use of chemical cues by a parasitoid. Anim. Behav. 77, 901–909 10.1016/j.anbehav.2008.12.016 (doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2008.12.016) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Soler R., et al. 2007. Root herbivores influence the behaviour of an aboveground parasitoid through changes in plant-volatile signals. Oikos 116, 367–376 10.1111/j.2006.0030-1299.15501.x (doi:10.1111/j.2006.0030-1299.15501.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Van Dam N. M., Poppy G. M. 2008. Why plant volatile analysis needs bioinformatics: detecting signal from noise in increasingly complex profiles. Plant Biol. 10, 29–37 10.1055/s-2007-964961 (doi:10.1055/s-2007-964961) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Poppy G. M., Powell W., Pennacchio F. 1997. Aphid parasitoid responses to semiochemicals: genetic, conditioned or learnt? Entomophaga 42, 193–199 10.1007/BF02769897 (doi:10.1007/BF02769897) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rasband W. S. 1997–2005. ImageJ. Bethesda, MD: US National Institutes of Health; See http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kappers I. F., Aharoni A., Van Herpen T. W. J. M., Luckerhoff L. L. P., Dicke M., Bouwmeester H. J. 2005. Genetic engineering of terpenoid metabolism attracts, bodyguards to Arabidopsis. Science 309, 2070–2072 10.1126/science.1116232 (doi:10.1126/science.1116232) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stewart-Jones A., Poppy G. M. 2006. Comparison of glass vessels and plastic bags for enclosing living plant parts for headspace analysis. J. Chem. Ecol. 32, 845–864 10.1007/s10886-006-9039-6 (doi:10.1007/s10886-006-9039-6) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Van Driesche R. G., Bellows T. S. 1996. Biological control. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers Group [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shiojiri K., Ozawa R., Kugimiya S., Uefune M., van Wijk M., Sabelis M. W., Takabayashi J. 2010. Herbivore-specific, density-dependent induction of plant polatiles: honest or ‘cry wolf’' signals? PLoS ONE 5, e12161 10.1371/journal.pone.0012161 (doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0012161) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gols R., Roosjen M., Dijkman H., Dicke M. 2003. Induction of direct and indirect plant responses by jasmonic acid, low spider mite densities, or a combination of jasmonic acid treatment and spider mite infestation. J. Chem. Ecol. 29, 2651–2666 10.1023/B:JOEC.0000008010.40606.b0 (doi:10.1023/B:JOEC.0000008010.40606.b0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Horiuchi J., Arimura G., Ozawa R., Shimoda T., Takabayashi J., Nishioka T. 2003. A comparison of the responses of Tetranychus urticae (Acari: Tetranychidae) and Phytoseiulus persimilis (Acari: Phytoseiidae) to volatiles emitted from lima bean leaves with different levels of damage made by T. urticae or Spodoptera exigua (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Appl. Entomol. Zool. 38, 109–116 10.1303/aez.2003.109 (doi:10.1303/aez.2003.109) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schoonhoven L. M., Jermy T., Loon J. J. A. V. 1998. Insect–plant biology: from physiology to evolution. London, UK: Chapman & Hall [Google Scholar]

- 44.Galizia C. G., Menzel R. 2000. Probing the olfactory code. Nat. Neurosci. 3, 853–854 10.1038/78741 (doi:10.1038/78741) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Galizia C. G., Menzel R. 2001. The role of glomeruli in the neural representation of odours: results from optical recording studies. J. Insect Physiol. 47, 115–130 10.1016/S0022-1910(00)00106-2 (doi:10.1016/S0022-1910(00)00106-2) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Reddy G. V. P., Holopainen J. K., Guerrero A. 2002. Olfactory responses of Plutella xylostella natural enemies to host pheromone, larval frass, and green leaf cabbage volatiles. J. Chem. Ecol. 28, 131–143 10.1023/A:1013519003944 (doi:10.1023/A:1013519003944) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ozawa R., Shiojiri K., Sabelis M. W., Takabayashi J. 2008. Maize plants sprayed with either jasmonic acid or its precursor, methyl linolenate, attract armyworm parasitoids, but the composition of attractants differs. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 129, 189–199 10.1111/j.1570-7458.2008.00767.x (doi:10.1111/j.1570-7458.2008.00767.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Turlings T. C., Fritzsche M. E. 1999. Attraction of parasitic wasps by caterpillar-damaged plants. Novartis Found Symp 223, 21–32 (discussion 32–8) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Auger J., Lecomte C., Paris J., Thibout E. 1989. Identification of leek-moth and diamondback-moth frass volatiles that stimulate parasitoid, Diadromus pulchellus. J. Chem. Ecol. 15, 1391–1398 10.1007/BF01014838 (doi:10.1007/BF01014838) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Alborn T., Turlings T. C. J., Jones T. H., Stenhagen G., Loughrin J. H., Tumlinson J. H. 1997. An elicitor of plant volatiles from beet armyworm oral secretion. Science 276, 945–949 10.1126/science.276.5314.945 (doi:10.1126/science.276.5314.945) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mithöfer A., Wanner G., Boland W. 2005. Effects of feeding Spodoptera littoralis on lima bean leaves. II. Continuous mechanical wounding resembling insect feeding is sufficient to elicit herbivory-related volatile emission. Plant Physiol. 137, 1160–1168 10.1104/pp.104.054460 (doi:10.1104/pp.104.054460) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Turlings T. C. J., Alborn H. T., Loughrin J. H., Tumlinson J. H. 2000. Volicitin, an elicitor of maize volatiles in oral secretion of Spodoptera exigua: isolation and bioactivity. J. Chem. Ecol. 26, 189–202 10.1023/A:1005449730052 (doi:10.1023/A:1005449730052) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Turlings T. C. J., Tumlinson J. H., Lewis W. J. 1990. Exploitation of herbivore-induced plant odors by host-seeking parasitic wasps. Science 250, 1251–1253 10.1126/science.250.4985.1251 (doi:10.1126/science.250.4985.1251) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]