Abstract

This study evaluates the levels of total polyphenolic compounds in three Malian medicinal plants and determines their antioxidant potential. Quantitative and qualitative analysis of polyphenolics contained in plants extracts were carried out by RP-C18 RP–HPLC using UV detector. The antioxidant activity was determined by three tests. They are phosphomolybdenum, DPPH (2,2-diphenyl-1 picrylhydrazyl) and ABTS [2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic)] tests. The total phenolic and the total flavonoid contents varied from 200 to 7600 mg 100 g−1 dry weight (dw), expressed as gallic acid equivalents and from 680 to 12 300 mg 100 g−1 dw expressed as catechin equivalents, respectively. The total anthocyanin concentrations expressed as cyanin-3-glycoside equivalent varied from 1670 to 28 388 mg 100 g−1 dw. The antioxidant capacity was measured by determining concentration of a polyphenolic (in mg ml−1) required to quench the free radicals by 50% (IC50) and expressed as vitamin C equivalent antioxidant capacity. The IC50 values were ranked between 2.68 and 8.80 μg ml−1 of a solution of 50% (v/v) methanol in water. The uses of plants are rationalized on the basis of their antioxidant capacity.

1. Introduction

Several epidemiological studies suggest that plants rich in antioxidants play a protective role in health and against diseases [1], and their consumption lowered risk of cancer, heart disease, hypertension and stroke [2–4]. The major groups of phytochemicals that may contribute to the total antioxidant capacity of plant include polyphenols and vitamins (C and E). Phenolic compounds can be nonnutrients [5]. Phenolic compounds of plants are hydroxylated derivatives of benzoic acid and cinnamic acids and have been reported to possess antioxidative and anticarcinogenic effects. Phenolic compounds including flavonoids are important in plant defense mechanisms against invading bacteria and other types of environmental stress [5, 6]. Flavonoids have long been recognized to possess anti-inflammatory, anti-allergic, antiviral and antiproliferative activities [5–9]. Several reports indicate that the antioxidant potential of medicinal plants may be related to the concentration of their phenolic compounds which include phenolic acids, flavonoids, anthocyanins and tannins [10, 11]. These compounds are of great value in preventing the onset and/or progression of many human diseases [12]. The health-promoting effect of antioxidants from plants is thought to arise from their protective effects by counteracting reactive oxygen species [11]. Antioxidants are compounds that help delay and inhibit lipid oxidation and when added to foods tend to minimize rancidity, retard the formation of toxic oxidation products, help maintain the nutritional quality and increase their shelf life [13].

We have recently reported the evaluation of the antioxidant potential of some medicinal and dietary plants [14, 15] and the positive correlation between peripheral blood granulocyte oxidative status and level of anxiety in mice [15–17].

The objectives of this investigation are (i) to evaluate the level of total phenolics, flavonoids and anthocyanins in three sub-Saharian medicinal plants (Daniella oliveri, Ficus capensis and Vitex doniana) used for treating hypertension and considered as diuretic, anti-inflammatory, antipyretic and antipurulent agents (Table 1) and (ii) to evaluate total antioxidant potential by using vitamin C equivalent antioxidant capacity (VCEAC) tests.

Table 1.

Name, traditional uses and phytocomponents data.

| Plant name | Family | Uses | Pharmacology data | Phytocomponents data |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Daniella oliveri (D. thurifera) Rolfe | Caesalpiniaceae | Treatment diarrheic (leaves), Bactericide, anti-inflammatory, analgesic, antiseptic, anti-diabetic, antispasmodic, anti-haemorrhoid, aphrodisiac, relaxing | Analgesic (hexane extract), antipyretic (ethyl acetate extract), anti-inflammatory, bactericide, anti-histamic (methanol extract) [18–21] | Polyphenols, flavonoids, anthocyanins, glycosides, tannins, saponins, terpenes, alkaloids |

|

| ||||

| Vitex doniana (V. umbrosa) | Verbenaceae | Bactericide (leaves and stems); diuretic (leaves) tonifiant (roots); aphrodisiac (leaves, roots) [22, 23]; anti-diabetic (stems) antiseptic (leaves) | Bactericide (aqueous extract) | Saponins, steroids, terpene, [24] flavonoids, polyphenols, vitamins C, A, E |

|

| ||||

| Ficus capensis (Thumb) (Forssk) | Moraceace | Bactericide, anti-diabetic, diuretic, aphrodisiac (stems, roots) [20, 25, 26] | Anti-diabetic, diuretic (methanol extract) | Polyphenols, flavonoids, tannins, vitamin C |

2. Methods

2.1. Apparatus

The RP–HPLC analyses were performed with a Waters 600E pump coupled to a Waters 486 UV visible tunable detector and equipped with a Alltech Intertsil ODS column (RP C18 column size 4.6 mm × 150 mm; particle size, 5 μm). In addition, spectrophotometer analyses were carried out with UV-Vis spectrophotometer (Cary 50 scan).

2.2. Chemicals

Folin-Ciocalteu's phenol reagent, aluminum chloride, catechin, gallic acid, p-coumaric acid, coumarin, rutin, protocatechic acid, vitamin acid, caffeic acid, isovitexin, chlorogenic acid, delphinidin, orientin, malvidin, homoorientin, ellagic acid, l-cyanidin, peonidin were purchased from Across Organics. Sodium carbonate, sodium nitrite, chlorhydric acid, ethyl acetate, sodium sulfate anhydrous, ammonium phosphate, ferric ammonium sulfate, acetonitrile, methanol, 2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic) (ABTS), PBS buffer, AAPH [2,2′-azo-bis(2-amidino-propane)dihydrochloride; ABTS: 2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic)] and DPPH (2,2-diphenyl-1 picrylhydrazyl) were obtained from Sigma and Roth (France). The chemicals used were all of analytical grade.

2.3. Procurement and Preparation of Samples

The plants D. oliveri, F. capensis and V. doniana were obtained from the Department of Traditional Medicine of Mali, upon arrival at the laboratory, different parts of the plants (leaves, root barks and stem barks) were dried at room temperature, powdered and sifted in a sieve (0.750 μm). The plant material was biologically authenticated by the National Institute for Research in Public Health of Bamako.

2.4. Samples Extractions

2.4.1. Total Phenolic, Flavonoid, Anthocyanin Contents and Antioxidant Capacity

Samples for total phenolic compounds (TPC), total flavonoid compounds (TFC), total anthocyanin compounds (TAC) and total antioxidant capacity assays were extracted from the different powders as described by Makkard et al. [27] slightly modified. The powder sample (2 g) was extracted twice with 20 ml of cold aqueous methanol solution (50%). The two volumes were combined, made up to 40 ml, centrifuged at 1238 g for 20 min and transferred in small sample bottles and stored at +4°C in the dark until analysis.

2.4.2. Extraction of Polyphenol Compounds for RP–HPLC Analysis

Polyphenols were extracted following the method described by Muchuweti et al. [28] slightly modified. Fresh samples (5 g) of plants portions were extracted twice with ethyl acetate (20 ml) and organic fractions were combined. After 30 min of drying with anhydrous NaSO4, the extract was evaporated to dryness at 40°C. Then, the residue was dissolved in methanol/water [2 ml 1 : 1(v/v)] before analysis by RP–HPLC. The standard solutions were prepared by dissolving 1 mg ml−1 (m/v).

2.5. Dosage of Phenolic Compounds

2.5.1. Spectrophotometer Analysis

Dosage of TPC —

TPC were determined following Muchuweti et al. [28] method which was slightly modified. To a sample of 100 μl, distilled water was added to make the quantity 2 ml (Eppendorff tube), followed by addition of 1 ml of Folin-Ciocalteu reagent (1N) and sodium carbonate (20%). After 40 min at room temperature, absorbance at 725 nm was read on a spectrophotometer against a blank that contained methanol instead of sample. TPC were expressed in terms of equivalent amounts of gallic acid (GAE).

Determination of TFC —

TFCs were measured according to a colorimetric assay slightly modified [12, 29]. A 250 μl of standard solution of catechin at different concentrations or appropriately diluted samples was added to 10 ml volumetric flask containing 1 ml of didistillate waters (ddH2O). At time 0 min, 75 μl of NaNO2 (5%) was added to the flask. After 5 min, 75 μl of AlCl3 (10%) was added. At 6 min, 500 μl of NaOH (1N) was added to the mixture. Immediately, the solution was diluted by adding 2.5 ml ddH2O and mixed thoroughly. Absorbance of the mixture, pink in color, was determined at 510 nm versus the prepared blank. TFCs in medicinal plants were expressed as microgram-catechin equivalents (CE)/gram dry weight (dw). Samples were analyzed in three replications.

Evaluation of TAC —

The anthocyanin contents of samples was estimated by a UV-spectrophotometer with the pH-differential method [30, 31] using two buffer systems, potassium chloride buffer, pH 1.0 (0.025 M) and sodium acetate buffer, pH 4.5 (0.4 M). Briefly, 400 μl of extract was mixed in 3.6 ml of corresponding buffer solutions and read against a blank at 510 and 700 nm. Absorbance (ΔA) was calculated as: ΔA = (A 510 − A 700) pH1.0 − (A 510 − A 700) pH4.0 [30–32]. Monomeric anthocyanin pigment concentration in the extract was calculated and expressed as cyaniding −3 glycoside (mg l−1): ΔA × MW × Df × 1000/(Ma × 1) [30–33] with ΔA: Absorbance, Mw: molecular weight (449.2), Ma: Molecular absorptivity (26.900) and Df: dilution factor.

2.5.2. RP–HPLC Analysis

RP-RP–HPLC analysis was performed according to the modified method describe [34, 35]. Extracted sample was filtered through a 0.45-μm polytetrefluoroethylene syringe tip filter, using a 20-μl sample loop. The sample was analyzed using an RP–HPLC system equipped with a waters UV-Visible tunable detector on a Reverse Phase (RP C18) column Alltech Intertsil ODS-5 μm × 4.6 mm × 150 mm. The flow rate was set at 1 ml min−1 at room temperature. A gradient of three mobile phases was used in the study, solvent A: 50 mM ammonium phosphate (NH4H2PO4) pH 2.6 (adjusted with phosphoric acid); solvent B: Which was constituted of 80 : 20 (v/v) acetonitrile/solvent A, and solvent C, constituted of 200 mM phosphoric acid pH 1.5 (pH adjusted with ammonium hydroxide). The solvents were filtered through a Whatman Maidstone England paper No. 3 and putted in an ultrasonic apparatus for 25 min. The gradient profile was linearly change as follows (total 60 min): 100% solvent A at 0 min, 92% A/8% B at 4 min, 14% B/86% C at 10 min, 16% B/84% C at 22.5 min, 25% B/75% C at 27.5 min, 80% B/20% C at 50 min, 100% A at 55 min, 100% A at 60 min [36]. After each run, the system was reconditioned for 10 min before analysis of next sample. Under these conditions, 20 μl of sample were injected. All sample analysis was done in triplicate. Polyphenolic standards prepared by dissolving 1 mg ml−1 were used to generate characteristic UV spectra and calibration curves. The individual polyphenolic compounds in the sample were identified by comparison of their UV-visible spectra and their retention times with the spike of the corresponding polyphenolic standards.

The detection was carried out at 280 and 320 nm and their quantification was obtained by the comparison of the peaks area with the corresponding standards calibration curves. Collected results were reported as equivalent amount of commercial standard.

2.6. Antioxidant Activity

Three different tests have been used to determine the total antioxidant capacity: the phosphomolybdenum (PPM) test, the ABTS test and the DPPH test [37, 38].

2.6.1. PPM Test

The PPM assay is a DPPH scavenging method in which, hydrogen and electron transfer from antioxidant analytes to DPPH and Molybdenum(VI) complex occur in the DPPH and PPM. The transfers occur at different redox potentials in the two assays and also depend on the structure of antioxidant. Several flavonoids and phenols have been isolated from plant parts with potent DPPH scavenging activities [39], whereas the PPM method usually detects antioxidants such as vitamins C, E and some specific phenol [37]. In general, the extraction solvent affects the antioxidant capacity, the aqueous methanol extract showed better antioxidant activities than the organic extract, aqueous alcohol is considered to be the best solvent for the extraction of phenolic compounds from plant materials [40, 41].

The total antioxidant capacity of the plant extracts was measured by the method described by Prieto et al. [37]; 100 μl of the sample solution was mixed with 900 μl of the reagent solution (0.6 M sulfuric acid, 28 mM sodium phosphate and 4 mM ammonium molybdate) against a blank containing 100 μl of methanol mixed with 900 μl of reagent solution. The absorbance of the test sample was measured at 695 nm. The antioxidant activity was expressed as vitamin C equivalent (mg 100 g−1 dry matter).

2.6.2. ABTS Test

The method used in this test is the one developed by Vanden Berg et al. [38], slightly modified. One millimolar of AAPH solution was mixed with 2.5 mM ABTS as diammonium salt in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) solution 100 M potassium phosphate buffered (pH 7.4) containing 150 mM NaCl. The mixture was heated in a water bath at 68°C for 20 min. The concentration of the resulting blue-green ABTS radical anion solution was adjusted to an absorbance of 0.65 ± 0.02 at 734 nm. The sample solution (60 μl) was added to 2.94 ml of the resulting blue–green ABTS radical solution. The mixture, protected from light, was incubated in a water bath at 37°C for 20 min. Then the decrease of absorbance was measured at 734 nm. The control solution was consisted by 60 μl of methanol and 2.94 ml of ABTS radical anion solution. The stable ABTS radical anion scavenging activity of the plants phenolic compounds in the extracts was expressed as mg 100 g−1 dry plants powders and as mg 100 ml−1 standards compounds of VCEAC in 20 min. All radical stock solutions were prepared fresh daily.

2.6.3. DPPH Test

DPPH Evaluation —

The antioxidant activity of plant extract was estimated using a slight modification of the DPPH radical scavenging protocol reported by Chen et al. [42]; 1 ml of 100 μM DPPH solution in methanol was mixed with 0.1 ml of plant extract. The reaction mixture was incubated in the dark for 20 min and thereafter the optical density was recorded at 517 nm against the blank.

For the control, 1 ml of DPPH solution in methanol (100 μM) was mixed with 0.1 ml of methanol and optical density of the solution was recorded after 20 min. The decrease in optical density of DPPH on addition of test samples in relation to the control was used to calculate the antioxidant activity as percentage of inhibition (%IP) of DPPH radical, %IP = [(At 0 − At 20)/(At 0 × 1000)] [12, 43] where At 0: absorbance of the sample test after 0 min and At 20: absorbance of the control after 20 min. Each assay was carried out in triplicate.

From a plot of concentration against %IP, a linear regression analysis was performed to determine the IC50 value (concentration of a polyphenolic (in mg ml−1) required to quench the free radicals by 50%) for each plant extract. The DPPH radical scavenging activity of phenolic compounds was expressed as IC50 value in micrograms per milliliter of fresh weight. A low IC50 value represents a high antioxidant activity.

DPPH Determination —

The DPPH scavenging activity was determined using a modified method of Kim et al. [35]. To 2.90 ml of an aqueous methanol solution (50%) of 100 μM of DPPH, 100 μl of the plant extracts solution was added. The mixture was shaken and allowed to stand at 20°C in dark for 30 min. After the decrease in absorbance, the resulting solution was monitored at 517 nm. The DPPH radical scavenging activity of phenolic compounds was expressed as mg 100 g−1 of dry matter and as mg 100 ml−1 of VCEAC in 30 min. The control solution was consisted by 100 μl of methanol and 2.90 ml of DPPH solution. The radical solution was prepared daily.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Results are presented as mean ± standard error; statistical analysis of experimental result was based on analysis of variance. Significant difference was statistically considered at the level of P < .001.

3. Results

3.1. TPCs, TFCs and TACs

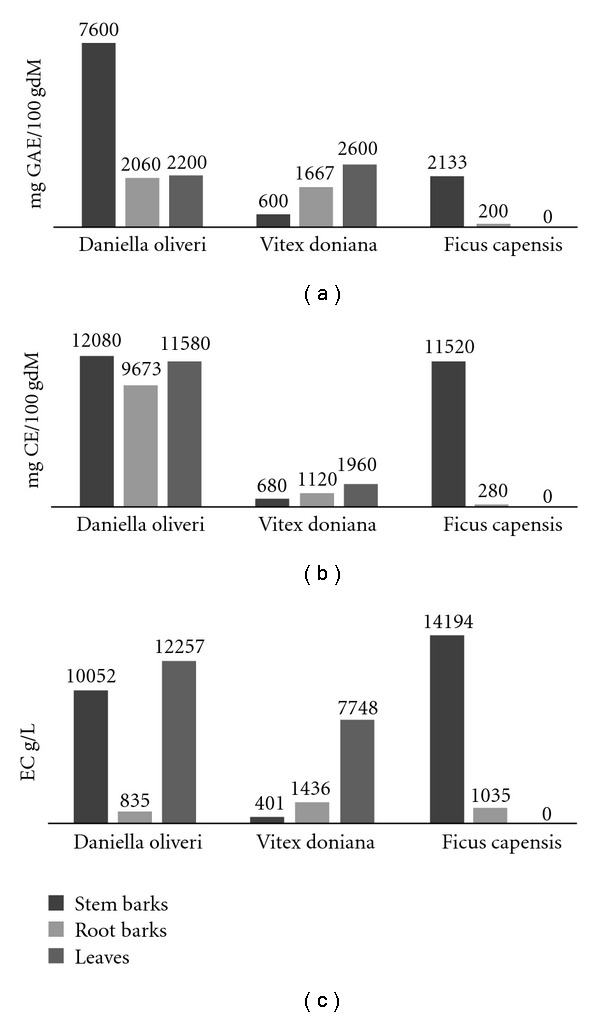

TPCs, TFCs and TACs were quantified using a UV-vis spectrophometric apparatus. The results of analysis are showed in Figure 1. No data were recorded for F. capensis leaves due to lack of sample.

Figure 1.

(a) Total polyphenols, (b) total flavonoids, (c) total anthocyanins.

3.2. RP–HPLC Analysis

Quantitative and qualitative comparison of polyphenolic compounds (TPC, TFC, TAC) were conducted using RP–HPLC.

The retention time of standards and their corresponding concentration in the samples were collected in Table 2. The experimentation has been done in four replicates. However, it is important to note that numerous peaks were not identified owing to the absence of suitable standards.

Table 2.

Compounds identified in the different plant parts and their concentration.

| Name of compound | Family | Retention time (min) | Stem barks (μg ml−1) | Root barks (μg ml−1) | Leaves (μg/ml) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D. oliveri | V. doniana | F. capensis | D. oliveri | V. doniana | F. capensis | D. oliveri | V. doniana | |||

| Gallic acid | P | 11.2 | 210.1 ± 1.5 | 190.9 ± 0.2 | 1180 ± 4 | 1202 ± 2 | 168.6 ± 0.4 | 1.6 ± 0.1 | 292.5 ± 0.3 | 471.4 ± 0.2 |

| Protocatechic acid | P | 17.0 | 19.8 ± 0.2 | 63.5 ± 1.4 | 71.6 ± 0.3 | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 22.7 ± 0.1 | 1.6 ± 0.1 | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 34.8 ± 0.3 |

| Catechin | F | 25.0 | ND | 10.4 ± 0.1 | 3.0 ± 0.1 | ND | 51.5 ± 0.2 | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 4.1 ± 0.1 | 1.4 ± 0.1 |

| Chlorogenic acid | P | 26.5 | 505.2 ± 0.4 | 4.2 ± 0.1 | 12.3 ± 0.1 | ND | ND | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 1.7 ± 0.1 |

| Caffeic acid | P | 28.7 | 2410.4 ± 12 | 8.2 ± 0.1 | 12.7 ± 0.1 | 0.9 ± 0.1 | ND | 5.2 ± 0.1 | 13.6 ± 0.2 | ND |

| p-Coumaric acid | P | 33.5 | 322.4 ± 3.7 | 9.2 ± 0.1 | 827.2 ± 3.5 | 127.6 ± 2.1 | ND | 827.2 ± 0.8 | 18.9 ± 0.2 | 18.8 ± 0.3 |

| Homo-orientin | F | 35.4 | 784.4 ± 4.9 | 453.6 ± 4.0 | 36.6 ± 0.1 | 6.2 ± 0.2 | 2804 ± 4 | 194.9 ± 0.3 | 894.9 ± 4.5 | 384.1 ± 2 |

| Orientin | F | 36.4 | ND | 3.8 ± 0.1 | 9.0 ± 0.1 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 247.1 ± 2.0 | 9.0 ± 0.1 | ND | 1.0 ± 0.2 |

| Rutin | F | 37.1 | 144.2 ± 2.4 | 34.9 ± 0.2 | 22.7 ± 0.2 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 6363 ± 2 | 6.1 ± 0.1 | ND | 11943 ± 5 |

| Quercitrin-glucosyl | F | 38.0 | 224.1 ± 0.7 | 96.3 ± 0.3 | ND | 115.6 ± 0.4 | 18.1 ± 0.1 | ND | 12.3 ± 0.2 | 12.6 ± 1 |

| Quercitrin dehydrate | F | 39.3 | 5.0 ± 0.2 | 78.7 ± 0.2 | 1.8 ± 0.1 | 22.4 ± 0.1 | 1346 ± 1 | 83.2 ± 0.5 | ND | 1.7 ± 0.1 |

| Coumarin | P | 40.4 | 1.9 ± 0.1 | 2.5 ± 0.1 | 13.8 ± 0.1 | 4.9 ± 0.1 | 33.9 ± 0.7 | 2.9 ± 0.1 | 29.2 ± 0.4 | 10.9 ± 0.1 |

| Malvidin | A | 42.0 | ND | 39.1 ± 0.2 | ND | ND | 110.0 ± 0.6 | ND | ND | 8.3 ± 0.1 |

| Delphinidin | A | 42.5 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 35.3 ± 0.1 | 34.4 ± 0.1 | ND | ND | 7.6 ± 0.1 | ND | ND |

| Quercitrin | F | 44.0 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | ND | 109.5 ± 1.0 | 5.0 ± 0.1 | 323.2 ± 0.1 | 63.3 ± 0.2 | ND | 1831 ± 18 |

| Ascorbic acid | Vit. C | 56.5 | 2.5 ± 0.1 | 1.6 ± 0.1 | 14.5 ± 0.4 | 4.0 ± 0.1 | ND | 1.3 ± 0.1 | ND | ND |

ND: not determinate; A: Anthocyanidins; F: Flavonoids; P: Polyphenol. Data were reported as mean ± SEM (n = 4).

3.3. Antioxidant Activity

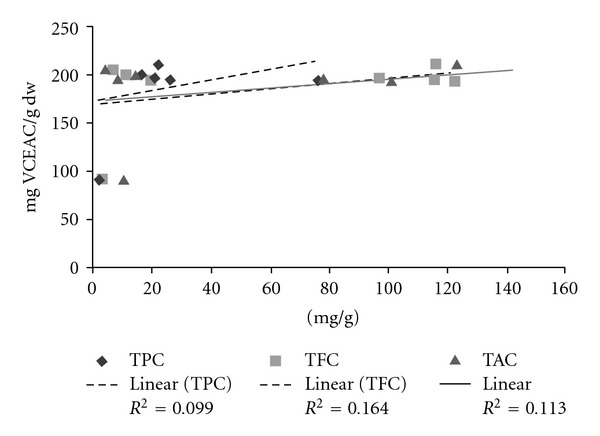

On the three plants screened, the extracts revealed good scavenging antioxidant activities as well as by PPM, ABTS or DPPH tests. The scavenging antioxidant activities of the different samples were reported in Table 3. Figure 2 showed the relationship between the antioxidant activities and the polyphenolic compounds (TPC, TFC, TAC) in the samples.

Table 3.

Antioxidant activity in vitro analysis.

| Plants | Parts | Test PPM (mg 100 g−1 dw) | Test ABTS (mg 100 g−1 dw) | Test DPPH | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VCEAC (mg 100 g−1 dw) | % IP | IC50 (μg ml−1) | ||||

| Daniella oliveri | Stem barks | 586 ± 12 | 127.5 ± 0.1 | 193.7 ± 1.8 | 86.1 ± 1.4 | 2.9 ± 0.1 |

| Root barks | 606 ± 1 | 124.1 ± 0.9 | 196.3 ± 0.7 | 87.6 ± 0.3 | 2.8 ± 0.1 | |

| Leaves | 526 ± 4 | 109.2 ± 3.8 | 210.3 ± 0.4 | 93.3 ± 0.2 | 2.7 ± 0.1 | |

| Vitex doniana | Stem barks | 74 ± 6 | 129.6 ± 0.1 | 205.5 ± 2.3 | 84.9 ± 1.3 | 2.9 ± 0.1 |

| Root barks | 194 ± 7 | 126.2 ± 0.9 | 200.1 ± 1.1 | 87.7 ± 0.1 | 2.8 ± 0.1 | |

| Leaves | 180 ± 5 | 127.1 ± 0.1 | 195.0 ± 1.3 | 84.9 ± 0.7 | 2.9 ± 0.1 | |

| Ficus capensis | Stem barks | 280 ± 3 | 120.8 ± 6.1 | 195.8 ± 3.3 | 85.40 ± 1.80 | 2.9 ± 0.1 |

| Root barks | 60 ± 2 | 122.5 ± 1.4 | 91.3 ± 0.5 | 28.41 ± 0.23 | 8.8 ± 0.1 | |

Figure 2.

Relationship between the antioxidant activities and the polyphenolic compounds TPC (Total Phenolic Compounds); TFC (Total Flavonoid compounds) and TAC (Total Anthocyanin Compounds).

4. Discussion

The distribution of TPC in D. oliveri and V. doniana differs. The content of TPC are higher in leaves than in stem barks in V. doniana, whereas in D. oliveri TPC is more concentrated in the stem barks (Figure 1). The concentration of TFC is very low in the root barks of F. capensis. The stem bark extracts of D. oliveri and F. capensis contain almost the same levels of TFC. Daniella oliveri plant parts, stem barks, root barks and leaves exhibit a similar TFC (Figure 1). For all the three plants, the concentration of TAC is lowest in the root barks.

RP–HPLC analysis revealed that the caffeic acid in the stem barks of D. oliveri is the most important phenolic compound (2410.4 μg ml−1), whereas its levels are too low in the other two plants (V. doniana, 8.2 μg ml−1 and F. capensis, 12.7μg ml−1). Moreover, it appears that rutin is in very high concentration (6363.0 μg ml−1) in the root barks of V. doniana and almost absent in the root barks of D. oliveri and F. capensis.

Rutin is the most important phenolic compound (11943.0 μg ml−1) in the leaves of V. doniana, while it is not detected in the leaves of D. oliveri (Table 2).

Antioxidant activity has been evaluated by three tests: PPM, ABTS and DPPH. The PPM assay showed that the highest value was 606.0 mg 100 g−1 dw (VCEAC) for the root barks of D. oliveri; in contrast, the lowest one was 60.0 mg 100 g−1 dw for the root barks of F. capensis (Table 3). The great variations observed between the different plants and plant parts could be explained by the fact that PPM essay evaluates the antioxidant activity of polyphenols, and others antioxidant agents which are not phenolic compounds [43]. To be more accurate about phenolic compounds, ABTS and DPPH tests have been done. ABTS tests showed that the antioxidant activity of different plants was almost the same. DPPH tests expressed as VCEAC varied from 91.3 mg 100 g−1 dw for the root barks of F. capensis to 205.5 mg 100 g−1 dw for the stem barks of V. doniana. In addition, the antioxidant activity evaluated as %IP revealed a similar behavior. The highest IP value was 93.3% for the stem barks of V. doniana and the lowest one was 28.4% for the root barks of F. capensis. The %IP and IC50 (μg ml−1) have been calculated to compare the antioxidant capacity of the studied plant parts extracts with those described by other authors in literature such as Adesegun et al. [44] and Ruchi et al. [43]. %IP values were relatively high (28.41–93.3%) and IC50 relatively weak (2.7–8.8 μg ml−1). This revealed that these three Malian plants have very good antioxidant activities. Each plant contains generally different phenolic compounds with different amount of antioxidant activity.

Many studies indicate linear relationship between total phenolics and antioxidant activity [10, 12, 45]. In this study we found that polyphenolic compounds were not major contributors to antioxidant activity, since for TPCs, TFCs and TACs versus antioxidant activity, the correlation coefficients R 2 = 0.0998, 0.1641, 0.1135, respectively, were weak (Figure 2). These correlations have been established using all plant parts (stem barks, root barks, leaves). In conclusion, our results suggest that these plants are strong radical scavengers and can be seen as potential source of natural antioxidants for medicinal and commercial uses.

Funding

Ministry of Scientific Research of the Republic Democratic of Congo grant (No. 132.49/060/KMB/07).

Acknowledgments

Mr Frédéric Desort (Ethnobotanique et Pharmacologie, Anxiété, Stress oxydant et Bioactivité. Université P. Verlaine-Metz, Metz, France) is acknowledged for technical assistance.

References

- 1.Milner JA. Functional foods and health promotion. Journal of Nutrition. 1999;129(7) doi: 10.1093/jn/129.7.1395S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Diaz MN, Frei B, Vita JA, Keaney JF., Jr. Antioxidants and atherosclerotic heart disease. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1997;337(6):408–416. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199708073370607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vinson JA, Su X, Zubik L, Bose P. Phenol antioxidant quantity and quality in foods: fruits. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2001;49(11):5315–5321. doi: 10.1021/jf0009293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wolfe K, Wu X, Liu RH. Antioxidant activity of apple peels. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2003;51(3):609–614. doi: 10.1021/jf020782a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ndhlala AR, Kasiyamhuru A, Mupure C, Chitindingu K, Benhura MA, Muchuweti M. Phenolic composition of Flacourtia indica, Opuntia megacantha and Sclerocarya birrea . Food Chemistry. 2007;103(1):82–87. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wallace G, Fry SC. Phenolic components of the plant cell wall. International Review of Cytology. 1994;151:229–267. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(08)62634-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frankel EN, Kanner J, German JB, Parks E, Kinsella JE. Inhibition of oxidation of human low-density lipoprotein by phenolic substances in red wine. The Lancet. 1993;341(8843):454–457. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)90206-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kuda T, Tsunekawa M, Goto H, Araki Y. Antioxidant properties of four edible algae harvested in the Noto Peninsula, Japan. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis. 2005;18(7):625–633. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sharma S, Stutzman JD, Kelloff GJ, Steele VE. Screening of potential chemopreventive agents using biochemical markers of carcinogenesis. Cancer Research. 1994;54(22):5848–5855. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Djeridane A, Yousfi M, Nadjemi B, Boutassouna D, Stocker P, Vidal N. Antioxidant activity of some algerian medicinal plants extracts containing phenolic compounds. Food Chemistry. 2006;97(4):654–660. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wong C-C, Li H-B, Cheng K-W, Chen F. A systematic survey of antioxidant activity of 30 Chinese medicinal plants using the ferric reducing antioxidant power assay. Food Chemistry. 2006;97(4):705–711. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim D-O, Chun OK, Kim YJ, Moon H-Y, Lee CY. Quantification of polyphenolics and their antioxidant capacity in fresh plums. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2003;51(22):6509–6515. doi: 10.1021/jf0343074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fukumoto LR, Mazza G. Assessing antioxidant and prooxidant activities of phenolic compounds. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2000;48(8):3597–3604. doi: 10.1021/jf000220w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bouayed J, Piri K, Rammal H, et al. Comparative evaluation of the antioxidant potential of some Iranian medicinal plants. Food Chemistry. 2007;104(1):364–368. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bouayed J, Djilani A, Rammal H, Dicko A, Younos C, Soulimani R. Quantitative evaluation of the antioxidant properties of Catha edulis . Journal of Life Sciences. 2008;2:7–14. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bouayed J, Rammal H, Dicko A, Younos C, Soulimani R. Chlorogenic acid, a polyphenol from Prunus domestica (Mirabelle), with coupled anxiolytic and antioxidant effects. Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 2007;262(1-2):77–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2007.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bouayed J, Rammal H, Younos C, Soulimani R. Positive correlation between peripheral blood granulocyte oxidative status and level of anxiety in mice. European Journal of Pharmacology. 2007;564(1-3):146–149. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.02.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ahmadu A, Haruna AK, Garba M, Ehinmidu JO, Sarker SD. Phytochemical and antimicrobial activities of the Daniellia oliveri leaves. Fitoterapia. 2004;75(7-8):729–732. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2004.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Balogun EA, Adebayo J. Effect of ethanolic extract of Daniella oliveri leaves on some cardiovascular indices in rats. Pharmacognosy Magazine. 2008;4:16–20. [Google Scholar]

- 20.El-Mahmood AM, Doughari JH, Chanji FJ. In vitro antibacterial activities of crude extracts of Nauclea latifolia and Daniella oliveri . Scientific Research and Essays. 2008;3(3):102–105. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Onwukaeme ND, Lot TY, Udoh FV. Effects of Daniellia oliveri stem bark and leaf extracts on rat skeletal muscle. Phytotherapy Research. 1999;13(5):419–421. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1573(199908/09)13:5<419::aid-ptr470>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ouattara F. Traitement traditionnelle des infections sexuellement transmissibles au Mali: etude de la phytochimie et des activités biologiques des Annona senegalesis L. (Annonaceae) et de stochytarpheta augustifolia Valh (Verbenaceae) Université de Bamako; 2005. Thèse de doctorat. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goetz P. Traitement des troubles de la libido masculine. Phytothérapie Clinique. 2006;1:9–14. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Higham JP, Ross C, Warren Y, Heistermann M, MacLarnon AM. Reduced reproductive function in wild baboons (Papio hamadryas anubis) related to natural consumption of the African black plum (Vitex doniana) Hormones and Behavior. 2007;52(3):384–390. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2007.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baldé NM, Youla A, Balde MD, et al. Herbal medicine and treatment of diabetes in Africa an example from Guinea. Diabetes & Metabolism. 2007;32(2):171–175. doi: 10.1016/s1262-3636(07)70265-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peter AG, Desmet M. Traditional pharmacognosy and medicine in Africa ethnopharmacological in sub-saharan art objet and utensils. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 1999;63:1–175. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(98)00031-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Makkar HPS. Quantification of Tannins in Tree Foliage: A Laboratory Manual for the FAO/IAEA Co-ordinate Research Project on Use of Nuclear and Related Techniques to Develop Simple Tannin Assay for Predicting and Improving the Safety and Efficiency of Feeding Ruminants on the Tanniniferous Tree Foliage. Vienna, Austria: Joint FAO/IAEA Division of nuclear techniques in Food and Agriculture; 1999. pp. 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Muchuweti M, Ndhlala AR, Kasiamhuru A. Analysis of phenolic compounds including tannins, gallotannins and flavanols of Uapaca kirkiana fruit. Food Chemistry. 2006;94(3):415–419. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhishen J, Mengcheng T, Jianming W. The determination of flavonoid contents in mulberry and their scavenging effects on superoxide radicals. Food Chemistry. 1999;64(4):555–559. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sellappan S, Akoh CC, Krewer G. Phenolic compounds and antioxidant capacity of Georgia-grown blueberries and blackberries. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2002;50(8):2432–2438. doi: 10.1021/jf011097r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sellappan S, Akoh CC. Flavonoids and antioxidant capacity of Georgia-grown Vidalia onions. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2002;50(19):5338–5342. doi: 10.1021/jf020333a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lako J, Trenerry VC, Wahlqvist M, Wattanapenpaiboon N, Sotheeswaran S, Premier R. Phytochemical flavonols, carotenoids and the antioxidant properties of a wide selection of Fijian fruit, vegetables and other readily available foods. Food Chemistry. 2007;101(4):1727–1741. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Prior RL, Cao G. Antioxidant phytochemicals in fruits and vegetables: diet and health implications. HortScience. 2000;35(4):588–592. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Arnao MB, Cano A, Acosta M. The hydrophilic and lipophilic contribution to total antioxidant activity. Food Chemistry. 2001;73(2):239–244. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim D-O, Lee KW, Lee HJ, Lee CY. Vitamin C equivalent antioxidant capacity (VCEAC) of phenolic phytochemicals. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2002;50(13):3713–3717. doi: 10.1021/jf020071c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Donovan JL, Meyer AS, Waterhouse AL. Phenolic Composition and Antioxidant of prunes and prunes juice (Prunus domestica) Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 1998;46(4):1247–1252. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Prieto P, Pineda M, Aguilar M. Spectrophotometric quantitation of antioxidant capacity through the formation of a phosphomolybdenum complex: specific application to the determination of vitamin E. Analytical Biochemistry. 1999;269(2):337–341. doi: 10.1006/abio.1999.4019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Van den Berg R, Haenen GRMM, Van den Berg H, Bast A. Applicability of an improved Trolox equivalent antioxidant capacity (TEAC) assay for evaluation of antioxidant capacity measurements of mixtures. Food Chemistry. 1999;66(4):511–517. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee SK, Mbwambo ZH, Chung H, et al. Evaluation of the antioxidant potential of natural products. Combinatorial Chemistry and High Throughput Screening. 1998;1(1):35–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Antolovich M, Prenzler P, Robards K, Ryan D. Sample preparation in the determination of phenolic compounds in fruits. Analyst. 2000;125(5):989–1009. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Negi PS, Jayaprakasha GK, Jena BS. Antioxidant and antimutagenic activities of pomegranate peel extracts. Food Chemistry. 2003;80(3):393–397. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen Y, Wang M, Rosen RT, Ho C-T. 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl radical-scavenging active components from Polygonum multiflorum Thunb. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 1999;47(6):2226–2228. doi: 10.1021/jf990092f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Marwah RG, Fatope MO, Mahrooqi RA, Varma GB, Abadi HA, Al-Burtamani SKS. Antioxidant capacity of some edible and wound healing plants in Oman. Food Chemistry. 2007;101(2):465–470. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Adesegun SA, Fajana A, Orabueze CI, Coker HAB. Evaluation of antioxidant properties of phaulopsis fascisepala C.B.Cl. (Acanthaceae) Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2009;6(2):227–231. doi: 10.1093/ecam/nem098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Van den Berg R, Haenen GRMM, Van den Berg H, Van der Vijgh W, Bast A. The predictive value of the antioxidant capacity of structurally related flavonoids using the Trolox equivalent antioxidant capacity (TEAC) assay. Food Chemistry. 2000;70(3):391–395. [Google Scholar]