Abstract

Direct endoscopic views of bile duct have been described in literature since the 1970s. Since then rapid strides have been made with the advent of technologically advanced systems with better image quality and maneuverability. The single operator semi-disposable per-oral cholangioscope and other novel methods such as the cholangioscopy access balloon are likely to revolutionize this field. Even though cholangioscopy is currently used primarily for characterization of indeterminate strictures and management of large bile duct stones, the diagnostic and therapeutic indications are likely to expand in future. The following is an overview of the currently available per-oral cholangioscopy equipments, indications for use and future directions.

Key words: cholangioscopy, per-oral cholangioscopy, endoscopic retrograde, cholangiopancreatography, biliary stricture

Introduction

The first endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatography (ERCP) was performed more than three decades ago and it has continued to evolve ever since. With the advent of safe and advanced pancreato-biliary imaging techniques like computed tomography (CT) scan, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) and endoscopic ultrasound (EUS), the use of diagnostic ERCP has decreased significantly.1 ERCP can outline the anatomy of the biliary tree and define any strictures or filling defects. However, ERCP guided cytology and biopsy has at best, modest sensitivity in diagnosing malignant lesions. The idea of direct visualization of the bile duct (cholangioscopy) has allured the gastroenterologist for more than a couple of decades now. The bile duct can now be accessed percutaneously and per-orally or intra-operatively via a choledochotomy or the cystic duct. This brief review will highlight the historical developments, currently available per-oral cholangioscopic equipment and techniques, indications and future prospects of this procedure.

Historical perspectives

Cholangioscopy was first introduced in the 1970s. The feasibility of percutaneous approach was first demonstrated in 1974 and per-oral approach simultaneously by two different teams in 1976.2–4 The initial procedures were carried out using a smaller scope (baby scope) inserted through the instrumentation channel of a large channel therapeutic duodenoscope (mother scope). This “mother and baby scope” approach is still the most commonly used cholangioscopic technique. Urakami et al carried out the first direct per-oral cholangioscopy using a straight-view endoscope.5 The initial procedures were hampered by technical limitations like poor image quality, small instrumentation channel limiting therapy, lack of tip deflection and air and water irrigation channels. With the introduction of video-endoscopes, the image quality has improved significantly. The baby scopes today have image enhancing capabilities (narrow band imaging or NBI) which have augmented the ability to differentiate benign from malignant lesions.6 The SpyGlass semi-disposable direct visualization system was first introduced in 2005 and it overcame a number of disadvantages posed by the mother and baby systems.7,8 The diagnostic and therapeutic uses of cholangioscopy will be discussed in the following sections.

Equipments and techniques

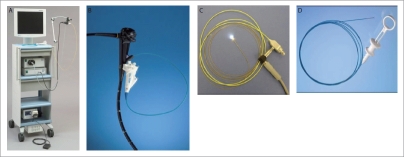

A brief comparison of the currently available cholangioscopic equipment is summarized in Table 1. These can be broadly classified into two-operator system or the single-operator systems. The two-operator system includes the conventional “mother and baby” system and needs the active participation of two endoscopists (Fig. 1). This system can be modified by securing the “baby” scope to a breast plate. A single experienced endoscopist can then hold the “mother” scope with the left hand and the right hand is free to control the “mother” or the “baby” in turn.9 The single operating systems include the SpyGlass direct visualization system (Boston Scientific, Natick, MA, USA) and the “ultra-slim” electronic gastroscope system.

Table 1.

Comparison of different per-oral cholangioscopic equipment

| Fibre-optic “baby” scopes | Video (electronic) “baby” scopes | SpyGlass direct visualization system | “Ultra-slim” electronic gastroscope system | |

| Number of operators | Two | Two | One | One |

| Tip deflection | Two way (up-down) | Two way (up-down) | Four way (up-down, left-right) | Four way (up-down, left-right) |

| Separate irrigation channel | No | No | Yes | No |

| Exchangeable optics | No | No | Yes | No |

| Image quality | Moderate to good | Excellent | Moderate to good | Excellent |

| Fragility | Yes | Yes | No* | No |

The SpyProbe component is fragile.

Figure 1.

Mother and baby cholangioscopy

Fiberoptic and Electronic “baby” scopes

The currently available fiberoptic baby scopes have an external diameter of 2.8 mm to 3.4 mm with a working channel varying from 0.5 mm to 1.2 mm. They have a single plane tip deflection (up-down) of approximately 90°. These systems are widely available, allow tissue biopsy and can be used for therapeutics. The electronic baby scopes have a charge-coupled device (CCD) video chip which is mounted at the distal tip of the scope (XCHF-B200, Olympus Optical Co., Hamburg, Germany).10,11 This scope has a vastly improved image quality but it lacks a working channel which forbids all therapeutics. A prototype electronic baby scope (Olympus XCHF-BP160F) has been developed which has an external diameter of 2.8 mm and includes a 1.2 mm working channel.12 However, the CCD of this scope is located at the control section which results in an inferior image. All baby scopes require a separate light source, image processor and a water-air pump. They are also fragile and can be easily damaged by the elevator of the mother duodenoscope. In addition, the tip deflection in only one plane and absence of an irrigation system also compromise the image quality when used in vivo.

SpyGlass™ direct visualization system

Developed by Boston Scientific (Boston Scientific, Natick, MA, USA), the SpyGlass direct visualization system (Fig. 2A–D), is a semi disposable, single operator cholangio-pancreatoscopy equipment which can be strapped on to the duodenoscope.7,8 It consists of three components:

Access and delivery catheter: SpyScope

Optical probe: SpyGlass

Biopsy forceps: SpyBite

Figure 2.

A: SpyGlass™ direct visualization system; B: SpyScope™; C: SpyGlass™; D: SpyBite™.

The SpyScope access and delivery catheter is a single use, single operator controlled, 10F, 230 cm long, four lumen catheter. It has an optical channel (0.9 mm) which accommodates the SpyGlass optical probe, a 1.2 mm accessory channel and two separate irrigation channels (each 0.6 mm). It incorporates a handle which allows four way tip deflection hence facilitating easier navigation in the bile duct.

The SpyGlass probe is a 0.77 mm diameter, 6000 pixel fiber optic bundle which enters the duct of interest through the SpyScope access and delivery catheter. It provides a 70° field of view and is 231 cm long. It has a central fiberoptic bundle for image acquisition which is surrounded by light fibers for illumination. This probe is fragile and needs to be carefully handled but can be reused.

The SpyBite biopsy forceps is a single use device which passes through the biopsy channel of the SpyScope catheter. Its jaws open to 4.1 mm allowing tissue biopsy which is adequate in a majority of cases.

In an initial feasibility study of the SpyScope access and delivery systems, Chen and Pleskow achieved procedural success in 32 out of 35 patients (91%) with indeterminate biliary strictures.8 Biopsy under direct vision was obtained in 71% patients with 71% sensitivity and 100% specificity in differentiating benign from malignant lesions. These initial results were further supported by a prospective international multicenter registry including 297 patients with a plethora of diagnostic and therapeutic indications for cholangioscopy.13 Overall success rate was reported to be 89% with a sensitivity of SpyGlass visual impression in diagnosing malignancy of 88%. Management of biliary stones was successful in 92% patients. Even though the image quality is inferior to the electronic baby scopes, four way tip deflection and separate irrigation channels help to keep a good luminal view clear of all debris. The SpyGlass access and delivery system has thus broadened the horizon of diagnostic and therapeutic cholangioscopy.

Ultra-slim endoscopes

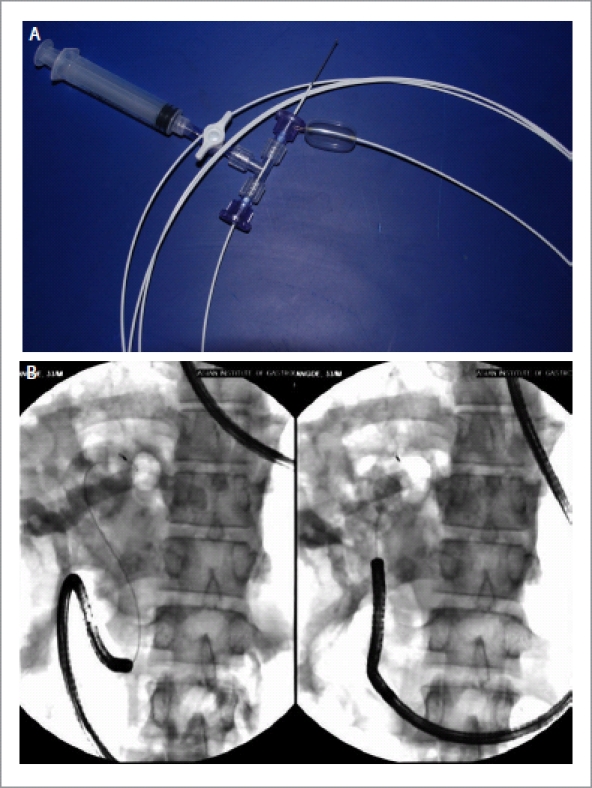

A number of ultra-slim endoscopes (5–6 mm) are currently available in the market. Each has a 2 mm working channel. They have the advantage of a superior image quality, providing larger biopsy samples and allowing a wide range of endoscopic therapies.14 Addition of narrow band imaging (NBI) allows superior visualization and identification of malignant lesions. Although direct per-oral cholangioscopy (POC) has been reported using free cannulation technique, the challenge in most cases is to negotiate them up the bile duct.15 This is carried out after a preliminary ERCP, a wide sphincterotomy and placement of a super-stiff 0.035-inch guidewire deep in the biliary system. The endoscope is then inserted over the guidewire and traversed cautiously into the duodenum and then up the ampulla of Vater under endoscopic and fluoroscopic guidance. Even with the guidewire in place, looping in the stomach and duodenum sometime result in failure to advance the scope into the bile duct. Looping can sometimes be prevented with the use of an overtube as demonstrated by Choi et al in their case series of 12 patients with various biliary diseases.16 Overtube-balloon-assisted direct cholangioscopy was performed successfully in 10 of the 12 patients (83.3%). In another series of 14 patients, Tsou et al demonstrated successful introduction of the ultra-slim endoscope into the bile ducts of all the patients using the overtube balloon-assisted technique.17 A feasibility study of balloon-guided direct P°C was carried out by Moon et al.18 Eleven patients underwent the traditional wire-guided POC as described above. Intraductal balloon-guided direct POC was carried out in 21 patients. A super-stiff guidewire was placed in the bile duct after ERCP and biliary sphincterotomy. The wire was then backloaded onto an ultra-slim endoscope through a 5F balloon catheter. The balloon catheter was advanced into an intra-hepatic duct over the guidewire and inflated to anchor it. The endoscope was then advanced over the balloon catheter into the bile duct. Wire-guided direct POC was successful in 5 of 11 patients (45.5%) and balloon-guided direct POC in 20/21 patients (95.2%; p<0.05). However, any therapeutic procedures will need the balloon to be withdrawn which may result in losing the scope position.

Recently, Cook Medical (Winston-Salem, NC, USA) has developed another anchoring system consisting of a 4F, multiple-stage, latex balloon (12, 15, 18 or 20 mm), 300 cm in length with a gold loop tip, which is radio-opaque to facilitate visualization (Fig. 3A,B). The core of the catheter contains a nitinol stiffening wire. The proximal end of the balloon has a detachable hub to enable backloading of the endoscope while maintaining an inflated balloon. This hub contains a plunger that secures a tapered plug that pushes into the catheter and releases once the desired balloon diameter is achieved. In a pilot study on porcine model, four animals underwent direct POC with this prototype balloon.19 Ductal access was achieved in 2 subjects after a sphincterotomy and 2 subjects after balloon sphincteroplasty. Intra-ductal placement of the ultra-slim endoscope was achieved in all 4 subjects with good visualization. Biliary perforation occurred in one case because of over-inflation of the balloon and another because of a sphincterotomy. Large human trials using this system are however awaited.

Figure 3.

A: Cook cholangioscopy access balloon; B: An ultraslim endoscope being pushed into the bile duct with the Cook cholangioscopy access balloon in situ.

To improve visualization, the issue of saline irrigation versus carbon dioxide (CO2) insufflation during POC was addressed in a small case-control study by Ueki and his colleagues.20 They carried out mother and baby cholangioscopy in 19 patients, 10 using CO2 insufflation and 9 using saline irrigation. The quality of images was found to be far superior with CO2 than saline irrigation. No serious adverse events or any significant change in venous partial pressure of CO2 level were noted. Moreover, the small risk of air embolism with cholangioscopy is also eliminated with the use of CO2.

Diagnostic applications

Cholangioscopy is of immense value in the diagnosis and subsequent treatment of biliary disorders that goes far beyond ERCP. Direct endoscopic views of indeterminate biliary strictures, filling defects and masses coupled with targeted biopsies can achieve the diagnosis in a majority of such cases. Most baby scopes these days are equipped with image enhancement facilities such as NBI which further aids in diagnosis. In addition, cholangioscopy can help in precise delineation of intraductal spread of malignancy prior to resection, collection of fluid for cytology or culture, visual analysis of post-transplant strictures, intra-ductal spread of an ampullary adenoma or characterization of a choledochal cyst.

Indeterminate biliary strictures/filling defects

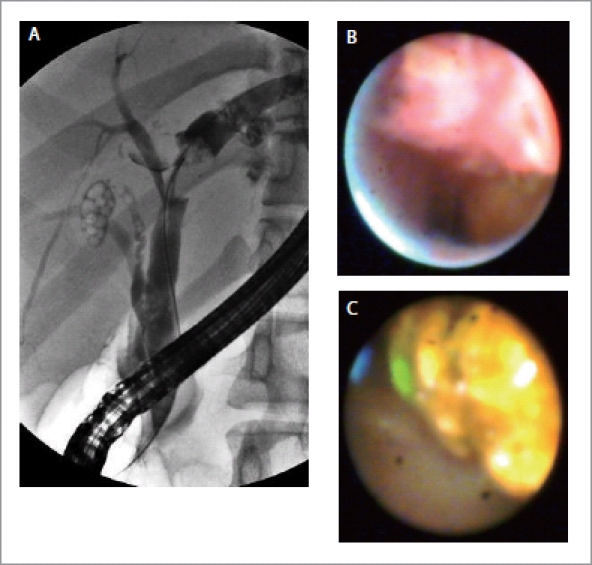

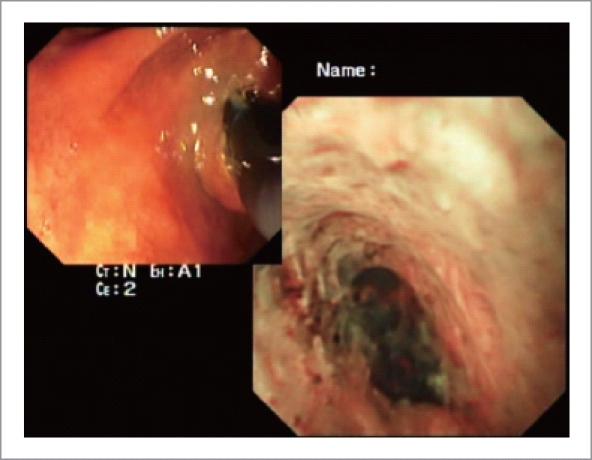

Traditionally ERCP has been used for the initial evaluation of patients presenting with obstructive jaundice and imaging studies suggesting a bile duct stricture with upstream biliary dilatation. However, it is limited in its capability to differentiate benign from malignant lesions. The diagnostic specificity of ERCP and brush cytology is very high but its sensitivity remains low despite modifications in the brush itself, balloon dilatation of the strictures prior to brushing or DNA methylation improves analysis of ERCP brush specimens.21–24 In a study by Fukuda et al, when cholangioscopy was carried out in addition to ERCP for evaluation of biliary strictures or filling defects, it increased the diagnostic accuracy from 78% to 93% and sensitivity from 58% to 100% (Fig. 4A–C).25 In another similar retrospective study, the diagnostic accuracy was reported to increase from 85% to 98% and sensitivity from 86% to 99%.26 On the basis of mucosal changes, presence of neovascularization and patterns of luminal narrowing on percutaneous cholangioscopy, Seo et al classified bile duct carcinoma into nodular, papillary and infiltrative types.27 The presence of an irregular, dilated and tortuous vessel (tumor vessel) is considered to be a diagnostic hallmark of malignancy on cholangioscopy (Fig. 5). In a prospective analysis of 63 patients, Kim HJ et al found that such vessels were present in 25 of the 41 patients with malignancy (61%). None of the patients with benign strictures had tumor vessels. Combining the observation of tumor vessel and percutaneous cholangioscopic-guided biopsy resulted in a diagnosis of malignancy in 39 of 41 patients (96%)28.

Figure 4.

A: Cholangiogram showing a filling defect in the left hepatic duct which could be a stone or a tumor; B: SpyGlass picture showing a nodular, irregular lesion suggestive of a malignancy; C: SpyGlass picture showing cholesterol stone in the bile duct.

Figure 5.

Cholangioscopic views of cholangiocarcinoma showing a nodular lesion with thick circuitous vessels

Cholangioscopy can thus help take targeted biopsies by accurate assessment of masses or nodules, tumor vessels or ulcerated and infiltrative lesions. Multiple biopsies increase the diagnostic sensitivity and specificity. When three biopsies were obtained from the margins of a stenotic cholangiocarcinoma rather than from the stricture itself, a positive diagnosis could be made in 95% cases.29 In a retrospective case review of 44 consecutive patients with localized type bile duct cancer, Kawakami et al compared the diagnostic accuracy to detect intra-epithelial tumor spread (ITS) beyond the visible tumor on ERCP, ERCP with POC and ERCP with POC plus mapping biopsy.30 ITS was correctly diagnosed in 22%, 77% and 100% cases, respectively. However, the cholangioscope could not be negotiated beyond the stricture in 15% of cases.

As mentioned previously, the 4-way steering system of the SpyGlass cholangioscopic system gives us the ability to negotiate and visualize deep into the biliary tree. In a novel application of the SpyGlass, Nguyen et al carried out POC in two patients using the SpyGlass in conjunction with a Tandem XL cannula (Boston Scientific, MA, USA) and a swing tip cannula (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). In the first patient, a filling defect in the left intra-hepatic duct was found to be a tumor and in the second case, they were able to clarify if complete clearance of the common bile duct has been achieved after mechanical lithotripsy of a large stone.31

The risk of developing cholangiocarcinoma in a patient with primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) has been reported to vary from 6–18%.32–34 The risk increases with dominant strictures. In a prospective study of 53 patients with PSC and dominant stenosis, POC and biopsy was carried out in addition to ERCP. Cholangioscopy was found to be significantly superior to ERCP for detecting malignancy in terms of its sensitivity (92% vs. 66%), specificity (93% vs. 51%), accuracy (93% vs. 55%), positive predictive value (79% vs. 29%), and negative predictive value (97% vs. 84%).35 The cholangioscopic findings of a malignant stricture included polypoid or villous masses and ulcerated mucosa. There was only one patient with false negative diagnosis of malignancy. Another prospective cohort study by Awadallah et al was carried out in 41 patients of PSC with mixed indications for cholangioscopy including evaluation of dominant strictures (n=35) and stone removal (n=6). Only a small number of PSC patients had a diagnosis of cholangiocarcinoma (n=3). Nevertheless, cholangioscopy-guided biopsies from the biliary stricture were taken in 15 patients. The adequacy of tissue sampling was satisfactory, with only one inadequate sample.36

Image enhanced cholangioscopy

Image enhancement of the endoscopically visualized mucosa can be carried out with dye, auto-fluorescence or NBI. When methylene blue dye solution is used during cholangioscopy, malignant lesions have an irregular mucosa with dark-blue staining pattern in contrast to benign lesions which have a smooth surface with uniform staining.37 Methylene blue chromo-cholangioscopy has also been used to characterize the features of ischemic type biliary lesions after liver transplantation.38 It permitted rapid discrimination between necrotic and normal areas of the bile duct. With autofluorescence, the neoplastic lesions appear dark green or black and benign lesions are green. However, it has a poor specificity which results in high false positive rates.39 NBI caused marked enhancement of the surface mucosal features and the mucosal blood vessels. Irregular and tortuous vessels suggest malignancy. In addition, the delineation of the proximal and distal margin of malignant lesions can be much better appreciated on NBI.40–41 Confocal fluorescence microscopy is another promising image enhancing technique used with cholangioscopy. In a preliminary study of 14 patients, mucosal imaging was performed with a miniaturized confocal laser scanning miniprobe introduced via the accessory channel of a cholangioscope and targeted biopsy specimens were taken. Presence of irregular vessels using this technique enabled prediction of malignancy with an accuracy rate of 86%, sensitivity of 83%, and specificity of 88%. The respective numbers for standard histopathology were 79%, 50%, and 100%.42

Thus, image enhancing techniques when used in combination with cholangioscopy help to distinguish benign from malignant biliary strictures. However, its true value needs further evaluation in prospective, randomized studies.

Missed stones

It is not uncommon to miss biliary stones during ERCP. Small stones may be easily obscured or masked in excessive contrast when injected by an over zealous assistant. In the study by Awadallah et al, calculi were not seen on ERCP in seven of 23 patients with PSC.36 In a recent study, stones were missed in 29% patients on ERCP which were detected when immediately followed by cholangioscopy.43 Cholangioscopy thus has a role to play in patients who continue to remain symptomatic despite satisfactory biliary clearance after ERCP.

Assessment of post liver transplant anastomotic strictures

Bile duct anastomotic strictures have long been considered the Achilles heel of liver transplantation. Cholangioscopy may be beneficial in the assessment of such strictures. Siddique et al reported their experience with choledochoscopy in sixty patients, twenty of whom had undergone prior liver transplantation.44 Cholangioscopy helped to diagnose ischemia, ulcers, scar tissue, blood clots and retained suture material. Importantly, it provided additional unsuspected diagnostic information in 18 of the 61 (29.5%) patients. The role of cholangioscopy is this field still needs further evaluation.

Other rare diagnostic applications

POC has also been reported to be useful in isolated case reports in determination of the source of bleeding in hemobilia45, evaluation of recurrent pancreatitis46, diagnosis and ablation of biliary neoplasm41,47,48 and diagnosis of recurrent bile duct stones post cholecystectomy.49

Therapeutic applications

The main therapeutic indications of cholangioscopy include management of difficult bile duct stones and palliative therapy for malignant obstructive jaundice. Several studies have also highlighted the value of cholangioscopy in guiding the passage of a guidewire across difficult biliary strictures and thus allowing endotherapy to proceed.50,51 Waxman et al have also described a through-the-scope, direct, cholangioscopic, selective biliary stent placement using an ultra-slim endoscope.15

Biliary calculi

Up to 95% of bile duct calculi can be removed during ERCP after a sphincterotomy and/or balloon sphincteroplasty and use of balloon extraction catheters, baskets or mechanical lithotripsy.52 However, at times, ERCP fails to clear all the calculi, especially the large ones. When the stones cannot be removed using conventional means, then they need to be pulverized using either laser lithotripsy (LL) or electro-hydraulic lithotripsy (EHL). Extra-corporeal shock wave lithotripsy (ESWL) has also been shown to be effective in clearing large CBD stones.53 Cholangioscopy is needed for intraductal EHL and LL. The stones need to be visualized directly so that the shock waves or laser are directed at the stone and not the bile duct wall which may result in bleeding or perforation. Various studies have reported high success rates ranging from 80% to 100% in clearing the bile ducts of stones after cholangioscopic EHL or LL.54–56 In a study by Neuhaus et al, comparing the efficacy of ESWL and cholangioscopy guided LL, the latter was found to be more effective in clearing bile duct stones (73% vs. 97%).57 After a cross-over to the LL arm, biliary clearance was achieved in seven out of eight patients who failed ESWL. Being much thinner than the EHL probe, LL is preferred to be used during cholangioscopy. LL is thus more suited for calculi within the intrahepatic ducts.54 Chen et al demonstrated a biliary clearance rate of 100% using SpyGlass directed EHL after failure of conventional ERCP techniques.8 Similarly, the international registry using SpyGlass achieved an overall success rate of 92% using either EHL or LL.13 Randomized trials comparing LL vs EHL using cholangioscopy for difficult biliary stones are awaited.

Palliative treatment of malignant obstructive jaundice

Cholangioscopy guided argon plasma coagulation for a hepatoma with intraductal growth has been described before.58 Recently, we also demonstrated successful ablation of cholangiocarcinoma using radiofrequency ablation.48 Lu XL et al have also used brachytherapy to ablate a mucin producing bile duct tumor which was confirmed using POC.41

Complications of cholangioscopy

Both diagnostic and therapeutic POC is generally safe. The complications of ERCP such as bleeding and perforation can occur during a preliminary sphincterotomy which is usually required prior to cholangioscopy. Similarly, pancreatitis is generally rare unless a large caliber cholangioscope is used without a generous sphincterotomy.59 The main concern is introduction of infection, especially in patients with PSC or difficult strictures or stones.60–62 Prophylactic antibiotics are recommended whenever there is concern of incomplete drainage of contrast. Mild self-limited hemobilia has been reported in some patients after cholangioscopy guided lithotripsy.9

Conclusion

POC plays an extremely important complimentary role in the diagnostic and therapeutic armamentarium of a host of biliary disorders. “Tissue being the main issue”, it helps in obtaining targeted biopsies from strictures and hence allowing accurate diagnosis and staging of bile duct neoplasia. However, the high initial and maintenance costs, have not allowed this technique to flourish and hence its use is limited to expert centers. With the development of new ultrathin endoscopes combined with NBI facility and the SpyGlass single operator cholangioscopy, this scenario is likely to change in the coming few years.

Abbreviations

- ERCP

endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatography

- CT: computed tomography; MRCP

magnetic resonance cholangio-pancreatography

- EUS

endoscopic ultrasound

- CCD

charge-coupled device

- NBI

narrow band imaging

- POC

peroral cholangioscopy

- ITS

intra-epithelial tumor spread

- PSC

primary sclerosing cholangitis

- LL

laser lithotripsy

- EHL

electrohydraulic lithotripsy

- ESWL

extra-corporeal shock wave lithotripsy

D. Nageshwar Reddy, MD, DM, DSc, FAMS, FRCP

Dr D Nageshwar Reddy is currently the Chairman of Asian Institute of Gastroenterology, Hyderabad, India.

He graduated from Kurnool Medical College obtaining internal medicine, Masters in Madras Medical College and D.M in Gastroenterology from PGIMER, Chandigarh. He subsequently worked as a Professor of Gastroenterology in Andhra Pradesh Health Sciences before setting up Asian Institute of Gastroenterology, a tertiary care Gastro intestinal Specialties Hospital.

His main areas of research interest has been in G.I.Endoscopy particularly in Therapeutic Pancreatio Biliary Endoscopy and Innovations in Transgastric Endoscopic Surgery. He has published over 170 papers in National & International Peer review journals and has contributed chapters in 7 International Text Books of Gastroenterology and has edited 3 G.I.Endoscopy Text Books. He is on the Editorial Board of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, Digestive Endoscopy, World Journal of Gastroenterology, World Gastroenterology News, Gastroenterology Today, The Journal of Chinese Clinical Medicine, Recent Patents on Medical Imaging, Indian Journal of Gastroenterology and Gastro-Hep.com. He is the peer reviewer of the Journals like Lancet, Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, Endoscopy, World Journal of Gastroenterology, Journal of Gastroenterology & Hepatology and Indian Journal of Gastroenterology. He was the President of Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy of India in 2001. He has been a visiting faculty for 112 international endoscopy workshops and forum member of Asian Endoscopy Masters Forum.

He has been recognized for his achievements by several societies. He has been elected as honorary member for American Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy in 2004, Fellow of Royal College of Physicians of Ireland in 2003, Fellow of National Academy of Medical Sciences, New Delhi in 2001, Fellow of Philippines Society of Gastroenterology in 2001 and is a recipient of Honorary Doctor in Sciences (D.Sc) from Nagarjuna University in 2005. He has given several named orations including The Francisco Roman oration of Philippines Society of Gastroenterology 2002, Dr Panner Selvam Memorial Oration of Malaysian Society of Gastroenterology in 2006, Kees Huibregtse Oration of 15th International Symposium on Pancreatio Biliary Endoscopy, Los Angeles 2008, Sir Francis Avery Jones Professorship in St. Marks, London 2008. Peter Gilispie Oration, Australia 2010. He received the Master Endoscopist Award from A.S.G.E in 2009 and International Service Award from ASGE in 2011.

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/jig/

References

- 1.Devereaux CE, Binmoeller KF. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in the next millennium. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2000;10:117–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Takada T, Suzuki S, Nakamura K, Uchida Y, Nomoto T, Yamada A, et al. Percutaneous transhepatic cholangioscopy as a new approach to the diagnosis of biliary disease. Gastroenterol Endosc. 1974;16:106–111. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nakajima M, Akasaka Y, Fukumoto K, Mitsuyoshi Y, Kawai K. Peroral cholangiopancreatosocopy (PCPS) under duodenoscopic guidance. Am J Gastroenterol. 1976;66:241–247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rosch W, Koch H, Demling L. Peroral cholangioscopy. Endoscopy. 1976;8:172–175. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Urakami Y, Seifert E, Butke H. Peroral direct cholangioscopy (PDCS) using routine straight-view endoscope: first report. Endoscopy. 1977;9:27–30. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1098481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Itoi T, Neuhaus H, Chen YK. Diagnostic value of image-enhanced video cholangiopancreatoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2009;19:557–566. doi: 10.1016/j.giec.2009.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen YK. Preclinical characterization of the Spyglass peroral cholangiopancreatoscopy system for direct access, visualization, and biopsy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;65:303–311. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2006.07.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen YK, Pleskow DK. SpyGlass single-operator peroral cholangiopancreatoscopy system for the diagnosis and therapy of bile-duct disorders: a clinical feasibility study (with video) Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;65:832–841. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2007.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Farrell JJ, Bounds BC, Al-Shalabi S, Jacobson BC, Brugge WR, Schapiro RH, et al. Single-operator duodenoscope-assisted cholangioscopy is an effective alternative in the management of choledocholithiasis not removed by conventional methods, including mechanical lithotripsy. Endoscopy. 2005;37:542–547. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-861306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kodama T, Imamura Y, Sato H, Koshitani T, Abe M, Kato K, et al. Feasibility study using a new small electronic pancreatoscope: description of findings in chronic pancreatitis. Endoscopy. 2003;35:305–310. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-38148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kodama T, Koshitani T, Sato H, Imamura Y, Kato K, Abe M, et al. Electronic pancreatoscopy for the diagnosis of pancreatic diseases. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:617–622. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05539.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kodama T, Tatsumi Y, Sato H, Imamura Y, Koshitani T, Abe M, et al. Initial experience with a new peroral electronic pancreatoscope with an accessory channel. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:895–900. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(04)01272-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Neuhaus H, Parsi MA, Binmoeller K, Stevens PD, Sherman S, Chen YK, et al. Peroral cholangioscopy for biliary strictures and bile duct stones- an international registry using SpyGlass. 2009 Abstract OP113, UEGW. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Larghi A, Waxman I. Endoscopic direct cholangioscopy by using an ultra-slim upper endoscope: a feasibility study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:853–857. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2005.07.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Waxman I, Chennat J, Konda V. Peroral direct cholangioscopic-guided selective intrahepatic duct stent placement with an ultraslim endoscope. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:875–878. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2009.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Choi HJ, Moon JH, Ko BM, Hong SJ, Koo HC, Cheon YK, et al. Overtube-balloon-assisted direct peroral cholangioscopy by using an ultra-slim upper endoscope (with videos) Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:935–940. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.08.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tsou YK, Lin CH, Tang JH, Liu NJ, Cheng CL. Direct peroral cholangioscopy using an ultraslim endoscope and overtube balloon-assisted technique: a case series. Endoscopy. 2010;42:681–684. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1255616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moon JH, Ko BM, Choi HJ, Hong SJ, Cheon YK, Cho YD, et al. Intraductal balloon-guided direct peroral cholangioscopy with an ultraslim upper endoscope (with videos) Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;70:297–302. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Waxman I, Dillon T, Chmura K, Wardrip C, Chennat J, Konda V. Feasibility of a novel system for intraductal balloon-anchored direct peroral cholangioscopy and endotherapy with an ultraslim endoscope (with videos) Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;72:1052–1056. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2010.06.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ueki T, Mizuno M, Ota S, Ogawa T, Matsushita H, Uchida D, et al. Carbon dioxide insufflation is useful for obtaining clear images of the bile duct during peroral cholangioscopy (with video) Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:1046–1051. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2010.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Glasbrenner B, Ardan M, Boeck W, Preclik G, Möller P, Adler G. Prospective evaluation of brush cytology of biliary strictures during endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Endoscopy. 1999;31:712–717. doi: 10.1055/s-1999-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fogel EL, deBellis M, McHenry L, Watkins JL, Chappo J, Cramer H, et al. Effectiveness of a new long cytology brush in the evaluation of malignant biliary obstruction: a prospective study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:71–77. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2005.08.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ornellas LC, Santos Gda C, Nakao FS, Ferrari AP. Comparison between endoscopic brush cytology performed before and after biliary stricture dilation for cancer detection. Arq Gastroenterol. 2006;43:20–23. doi: 10.1590/s0004-28032006000100007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Parsi MA, Li A, Li CP, Goggins M. DNA methylation alterations in endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography brush samples of patients with suspected pancreatico-biliary disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:1270–1278. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fukuda Y, Tsuyuguchi T, Sakai Y, Tsuchiya S, Saisyo H. Diagnostic utility of peroral cholangioscopy for various bile-duct lesions. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62:374–382. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2005.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Itoi T, Osanai M, Igarashi Y, Tanaka K, Kida M, Maguchi H, et al. Diagnostic peroral video cholangioscopy is an accurate diagnostic tool for patients with bile duct lesions. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:934–938. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2010.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Seo DW, Lee SK, Yoo KS, Kang GH, Kim MH, Suh DJ, et al. Cholangioscopic findings in bile duct tumors. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52:630–634. doi: 10.1067/mge.2000.108667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim HJ, Kim MH, Lee SK, Yoo KS, Seo DW, Min YI. Tumor vessel: a valuable cholangioscopic clue of malignant biliary stricture. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52:635–638. doi: 10.1067/mge.2000.108969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tamada K, Kurihara K, Tomiyama T, Ohashi A, Wada S, Satoh Y, et al. How many biopsies should be performed during percutaneous transhepatic cholangioscopy to diagnose biliary tract cancer? Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;50:653–658. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(99)80014-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kawakami H, Kuwatani M, Etoh K, Haba S, Yamato H, Shinada K, et al. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiography versus peroral cholangioscopy to evaluate intraepithelial tumor spread in biliary cancer. Endoscopy. 2009;41:959–964. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1215178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nguyen NQ, Shah JN, Binmoeller KF. Diagnostic cholangioscopy with SpyGlass probe through an endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography cannula. Endoscopy. 2010;42:E288–E289. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1255707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Farrant JM, Hayllar KM, Wilkinson ML, Karani J, Portmann BC, Westaby D, et al. Natural history and prognostic variables in primary sclerosing cholangitis. Gastroenterology. 1991;100:1710–1717. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(91)90673-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Burak K, Angulo P, Pasha TM, Egan K, Petz J, Lindor KD. Incidence and risk factors for cholangiocarcinoma in primary sclerosing cholangitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:523–526. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.04067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rosen CB, Nagorney DM, Wiesner RH, Coffey RJ, Jr, LaRusso NF. Cholangiocarcinoma complicating primary sclerosing cholangitis. Ann Surg. 1991;213:21–25. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199101000-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tischendorf JJ, Krüger M, Trautwein C, Duckstein N, Schneider A, Manns MP, et al. Cholangioscopic characterization of dominant bile duct stenoses in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis. Endoscopy. 2006;38:665–669. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-925257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Awadallah NS, Chen YK, Piraka C, Antillon MR, Shah RJ. Is there a role for cholangioscopy in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis? Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:284–291. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00383.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hoffman A, Kiesslich R, Bittinger F, Galle PR, Neurath MF. Methylene blue-aided cholangioscopy in patients with biliary strictures: feasibility and outcome analysis. Endoscopy. 2008;40:563–571. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-995688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hoffman A, Kiesslich R, Moench C, Bittinger F, Otto G, Galle PR, et al. Methylene blue-aided cholangioscopy unravels the endoscopic features of ischemic-type biliary lesions after liver transplantation. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:1052–1058. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2007.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Itoi T, Neuhaus H, Chen YK. Diagnostic value of image-enhanced video cholangiopancreatoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2009;19:557–566. doi: 10.1016/j.giec.2009.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Itoi T, Sofuni A, Itokawa F, Tsuchiya T, Kurihara T, Ishii K, et al. Peroral cholangioscopic diagnosis of biliary-tract diseases by using narrow-band imaging (with videos) Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:730–736. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2007.02.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lu XL, Itoi T, Kubota K. Cholangioscopy by using narrow-band imaging and transpapillary radiotherapy for mucin-producing bile duct tumor. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:e34–e35. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Meining A, Frimberger E, Becker V, Von Delius S, Von Weyhern CH, Schmid RM, et al. Detection of cholangiocarcinoma in vivo using miniprobe-based confocal fluorescence microscopy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:1057–1060. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen YK, Parsi MA, Binmoeller KF, Hawes RH, Pleskow D, Slivka A, et al. Peroral cholangioscopy (PJC) using a disposable steerable single operator catheter for biliary stone therapy and assessment of indeterminate strictures - A multicenter experience using SpyGlass. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:AB264–AB265. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Siddique I, Galati J, Ankoma-Sey V, Wood RP, Ozaki C, Monsour H, et al. The role of choledochoscopy in the diagnosis and management of biliary tract diseases. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;50:67–73. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(99)70347-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hayashi S, Baba Y, Ueno K, Nakajo M. Small arteriovenous malformation of the common bile duct causing hemobilia in a patient with hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2008;31:S131–S134. doi: 10.1007/s00270-007-9098-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Parsi MA, Sanaka MR, Dumot JA. Iatrogenic recurrent pancreatitis. Pancreatology. 2007;7:539. doi: 10.1159/000108972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Johnson G, Hatfield A, Webster G, Groves C, Rodriguez-Justo M. A diagnosis of an intraluminal carcinoid tumor of the bile duct by using cholangioscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:622–623. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2009.10.014. discussion 623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Monga A, Gupta R, Ramchandani M, Rao GV, Santosh D, Reddy DN. Endoscopic radiofrequency ablation of cholangiocarcinoma: new palliative treatment modality (with videos) Gastrointest Endosc. 2010 Dec 17; doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2010.10.018. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Agrawal D, Chak A. Peroral direct cholangioscopy for recurrent bile duct stones, using an ultrathin upper endoscope. Endoscopy. 2010;42:E190–E191. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1244224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Parsi MA, Guardino J, Vargo JJ. Peroral cholangioscopy-guided stricture therapy in living donor liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2009;15:263–265. doi: 10.1002/lt.21584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Parsi MA. Peroral cholangioscopy-assisted guidewire placement for removal of impacted stones in the cystic duct remnant. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;1:59–61. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v1.i1.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Van Dam J, Sivak MV., Jr Mechanical lithotripsy of large common bile duct stones. Cleve Clin J Med. 1993;60:38–42. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.60.1.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tandan M, Reddy DN, Santosh D, Reddy V, Koppuju V, Lakhtakia S, et al. Extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy of large difficult common bile duct stones: efficacy and analysis of factors that favor stone fragmentation. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;24:1370–1374. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2009.05919.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Neuhaus H, Hoffmann W, Zillinger C, Classen M. Laser lithotripsy of difficult bile duct stones under direct visual control. Gut. 1993;34:415–421. doi: 10.1136/gut.34.3.415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jakobs R, Pereira-Lima JC, Schuch AW, Pereira-Lima LF, Eickhoff A, Riemann JF. Endoscopic laser lithotripsy for complicated bile duct stones: is cholangioscopic guidance necessary? Arq Gastroenterol. 2007;44:137–140. doi: 10.1590/s0004-28032007000200010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Piraka C, Shah RJ, Awadallah NS, Langer DA, Chen YK. Transpapillary cholangioscopy-directed lithotripsy in patients with difficult bile duct stones. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:1333–1338. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Neuhaus H, Zillinger C, Born P, Ott R, Allescher H, Rösch T, et al. Randomized study of intracorporeal laser lithotripsy versus extracorporeal shock-wave lithotripsy for difficult bile duct stones. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;47:327–334. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(98)70214-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Park do H, Park BW, Lee HS, Park SH, Park JH, Lee SH, et al. Peroral direct cholangioscopic argon plasma coagulation by using an ultraslim upper endoscope for recurrent hepatoma with intraductal nodular tumor growth (with videos) Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:201–203. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2006.11.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chen YK. Pancreatoscopy: present and future role. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2007;9:136–143. doi: 10.1007/s11894-007-0008-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bogardus ST, Hanan I, Ruchim M, Goldberg MJ. “Mother-baby” biliary endoscopy: the University of Chicago experience. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:105–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Caldwell SH, Bickston SJ. Cholangioscopy to screen for cholangiocarcinoma in primary sclerosing cholangitis. Liver Transpl. 2001;7:380. doi: 10.1002/lt.500070417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Binmoeller KF, Brückner M, Thonke F, Soehendra N. Treatment of difficult bile duct stones using mechanical, electro hydraulic and extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy. Endoscopy. 1993;25:201–206. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1010293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]