Abstract

The disclosure of individual genetic research results to participants continues to be the subject of vigorous debate, centered primarily on the nature of the results: What are the criteria for the kinds of information that should, could, or should not be offered? There are widely diverging views about how to define these categories, as reasonable people can disagree about the value of various kinds of information. Data concerning participant preferences regarding receipt of results are important, but not determinative of researchers’ fundamental obligations.

We suggest that research context is a vital consideration that has not been sufficiently incorporated into the discussion. We adapt an ancillary care framework to explore what different contexts might call for with regard to offering individual genetic research results. Our analysis suggests that, beyond exceptionally rare circumstances that give rise to a duty to rescue, a “one size fits all” threshold cannot be developed for decisions about return of individual results. Instead, researchers and IRBs must consider the scope of entrustment involved in the research, the intensity and duration of interactions with participants, and the vulnerability and dependence of the study population. The strength of this approach is that research context is foreseeable at the time a study is designed. Assessments of the nature and value of the information may still be required to decide whether to offer a particular result, but perhaps will be facilitated by a more grounded understanding of researchers’ obligations in different contexts.

The disclosure of individual results to participants in genetic research continues to be the subject of vigorous debate. This debate has centered primarily on the nature of the results: What are the criteria for the kinds of information that should, could, or should not be offered to participants? Perhaps not surprisingly, there are widely diverging views about how to define these categories. Although many agree that results should be offered only when they have utility, opinions vary as to whether the line should be drawn at clinical utility (i.e., a proven therapeutic or preventive intervention is available), personal utility (e.g., for reproductive decision making or life planning), or in recognition that some individuals will find the information useful in and of itself (e.g., through an enhanced sense of personal identity).

Adding to the policy debate is a growing body of evidence documenting participants’ interest in receiving results (1, 2). Being responsive to participant preferences—within the parameters of the responsible use of research resources—may be consistent with the general ethical principles of respect for persons and beneficence (3) and may promote participation and public support of the research enterprise (4). There are good reasons, however, to be cautious in interpreting these data. First, survey responses may not reflect what participants’ nuanced preferences would be if they were given a more complete picture of the limited validity and utility of most individual findings (5). Second, the perceived worth of the information varies at an individual level. Any particular result could be viewed as harmful, depending on one’s circumstances and values (6). Some have therefore recommended that each participant be given the opportunity at the time of initial consent to choose whether and what kind of results to receive (7–9). However, even if these choices were periodically updated, it is difficult to imagine how participants could be given enough information to make a fully informed decision except at the time a specific result is available. Finally, focusing on fulfilling participants’ individual preferences, values, and goals inappropriately conflates research and medical care.

In this commentary, we suggest that researchers may choose to offer certain kinds of results based on knowledge of participants’ preferences, but such preferences should not define researchers’ fundamental obligations. Rather, we suggest that research context is a key consideration that has been little discussed but bears explicit analysis. We adapt an ancillary care framework to explore what different contexts might call for with regard to offering individual genetic research results. Assessments of the nature and value of the information may still be required to decide whether to offer a particular result, but perhaps will be facilitated by a more grounded understanding of researchers’ obligations in different contexts.

RESEARCHERS’ OBLIGATIONS AND THE IMPORTANCE OF CONTEXT

The goal of biomedical research is to produce generalizable knowledge that will eventually contribute to improved human health. In pursuing this goal, researchers must use sound methodology and uphold scientific integrity, minimize risks and burdens to participants, and exhibit respect for persons by obtaining participants’ voluntary informed consent, protecting their privacy and confidentiality, and ensuring their right to withdraw (10). As distinct from medical care, which requires that physicians optimize risk/benefit ratios and health outcomes for each patient, research does not require such proportionality. Within appropriate limits, it is ethically permissible to expose participants to risks that are justified by the value of the knowledge to be gained (10).

Within the research context, some studies are designed to examine participants’ understanding and use of genetic information. This is an important area of inquiry to inform the responsible translation of such information into clinical and public health practice, as well as to inform the debate about disclosure of individual research results. However, this aim is not intrinsic to most genetic research, nor should it be. If researchers do plan routinely to offer certain kinds of results, a systematic assessment of participants’ reactions would be desirable because we currently have limited knowledge about how individuals respond to health-related genetic information. But designing research with disclosure of individual genetic results as an integral component is a morally optional choice, not an obligation of all researchers.

Duty to Rescue – A Fundamental Obligation

The duty to rescue is based on the premise that, when confronted with a clear and immediate need, an individual who is in a position to help must take action to try to prevent serious harm when the cost or risk to self is minimal (11, 12). This condition is met when, in the course of research, an investigator discovers genetic information that clearly indicates a high probability of a serious condition for which an effective intervention is readily available.

These criteria closely resemble the high threshold for return of results recommended by the National Bioethics Advisory Commission (13), and are perhaps what Greely (14) had in mind when he suggested that the failure to return clinically meaningful research results to individuals “…seems, at least in extreme situations, immoral, possibly illegal, and certainly unwise” (p. 359). His example of such an extreme situation is the finding of a mutation conferring a high risk of early-onset colorectal cancer. Knowledge of the mutation could allow a person to pursue life-saving screening; absent a dramatic family history, the participant might be unaware of the risk. Given the relative novelty of genetic testing in general clinical practice, it is predictable that researchers who uncover this information will be among the few in a position to help, and they can provide this help at little cost to themselves or their studies.

Thus, we submit that uncovering individual results of this kind constitute a duty to rescue. Endorsement of this duty can be found even among those voicing opposition to the routine return of individual results. Parker (15), for example, affirms that goal of research is to provide societal benefit in the form of generalizable knowledge, not to address participant preferences for information—but allows that if a result meets “Tarasoff-informed criteria of a duty to warn or disclose, then arguably concern to protect the subject’s welfare would warrant the offer (perhaps even the imposition) of such highly valuable (read: reliable lifesaving or severe-morbidity-preventing) information” (p. 6).

Although the duty to rescue is a legal concept, our intent is to propose an ethical underpinning for what participants have called basic “human decency” when discussing researchers’ obligations concerning genetic information (4). Participants should be informed during the consent process that these kinds of results—which can be expected to be exceptionally rare—will be disclosed. Making this statement, without regard to choices participants might be given about what other results they do or do not want to receive, ameliorates the possibility of having to override their stated wishes.

Researchers’ Potential Obligations

When offering results is not necessary to complete the aims of the study and is not required by the duty to rescue, the concept of ‘ancillary care’ provides a useful framework for examining researchers’ obligations in different contexts. According to Richardson and Belsky (12, 16), ancillary care obligations are based on (i) the scope of what participants have entrusted to researchers, and (ii) the strength of the claims concerning researchers’ responsibilities.

Participants entrust certain aspects of their health to researchers when they enroll in a study, and the scope of this entrustment is set by the specific set of permissions researchers obtain during the informed consent process to carry out the study validly and safely (12). Thus, the scope of entrustment is partial and depends on the nature of the study.

In genomic research, the permissions obtained are often broad. For example, researchers may seek biospecimens for detailed genomic analysis and request ongoing access to participants’ medical records for studies of “how genes affect health, or how genes affect response to treatment” (17). Even when the initial study addresses a particular condition, consent is often requested to store materials for use in unspecified future research. (This is why separating ‘research results’ from ‘incidental findings’ based on whether the information is related to the study aims (7) is problematic for much genomic research and we do not make that distinction here.)

Thus, a statement of the scope entrustment for much genomic research might be “The role of genes in human health and disease.” Despite its breadth, this scope is not unlimited. The ultimate goal of much genomic research is improving health care, and the scope of entrustment would therefore not cover the entirety of participants’ well-being or matters of ‘personal meaning’ that have been argued as reasons to offer individual results (18). In addition, researchers are not automatically responsible for all aspects of health that fall within the scope of entrustment (12, 16). Several contextual factors influence the strength of the rationale for ascribing ancillary responsibilities:

Degree of vulnerability

During the informed consent process, participants grant researchers certain permissions, for example to collect biospecimens and confidential medical information. Participants thus become vulnerable to researchers’ discretionary power (16), in that researchers’ decisions about how to respond to the information they collect or generate may affect participants’ well being (12). This vulnerability may be compounded when participants are ill, or experiencing oppression or poverty (16).

Thus, the nature of the study population is an important contextual consideration. As Joffe and Franklin (10) note, the principle of respect for persons takes on additional dimensions when research is focused on sick individuals because of their status as patient-subjects, not just subjects. They further suggest that investigators must debrief patient-subjects at the conclusion of research, provide medically relevant information that has emerged during the course of research, and make appropriate referrals for or provide ongoing treatment.

With regard to genetic research, investigators who plan to recruit participants who have been diagnosed with a particular condition may decide to offer certain kinds of individual results beyond those required by the duty to rescue. For example, they may decide to offer results that inform participants’ understanding of their illness, even when clinical utility is not established. Such decisions can be made during the study design stage, as could plans to involve participants’ physicians in communication about results. The ancillary care framework suggests that the offer of such information may represent an obligation, rather than a choice, when the depth of the relationship and the degree of dependence between participant and researcher is sufficiently strong.

Depth of relationship

The depth of researcher-participant relationships will vary from study to study because different protocols demand interactions of varying intensity, duration, and longevity. Relationships may also be influenced by institutional commitments; for example, research undertaken within a health maintenance organization may be influenced by the institution’s commitment to its members’ health care. When considering ancillary care obligations, researchers have a stronger moral responsibility to engage with a fuller range of participants’ needs when the relationship is deeper (12).

The depth of relationships in genomic research can range from a single interaction to collect a biospecimen and snapshot of health information, to extensive ongoing interactions in community-based participatory research with disadvantaged populations (19). With the advent of large-scale repositories that facilitate unprecedented sharing, a rapidly increasing amount of genomic research can occur with no interaction at all between researchers and the individuals who contributed the specimens and/or data under study.

Depth of relationship is therefore a critical contextual factor in analyzing researchers’ obligations concerning genetic results. We suggest that it be assessed at the level of the investigator (or entity) who originally collects and stores the biospecimens and data for research, with the obligations extending to sharing the occurs under the control of that investigator. If these assessments indicate that the original collector has a responsibility to offer certain kinds of results, secondary users of the stored materials should be required (e.g., through material transfer agreements) to notify the original collector of such results.

When data are submitted to centralized repositories, such as dbGaP (20), subsequent sharing is no longer under the control of the original collector and may take place long after the original collector’s relationship with participants has ended. Informing participants during the original consent process that they will not receive individual results from this specific kind of sharing places a reasonable limit on researchers’ obligations.

Degree of gratitude

Researchers may owe a debt of gratitude to participants who have accepted uncompensated risks and burdens or offered researchers a hard to come by scientific opportunity (16). Although gratitude is an important consideration in determining ancillary care obligations in general, there are several reasons why it is less applicable for genetic research results.

Framing the offer of individual results as an expression of gratitude implies that participants will receive something of worth in exchange for taking part. In most cases, this would be an erroneous characterization of such results. Further, gratitude should not depend on researchers’ success in answering the study question (e.g., identifying a genetic trait associated with a health outcome) nor a participant’s relationship to the findings (e.g., possession of the genetic trait) (21, 22); out of fairness, it should be of established and relatively uniform value to all (15). Finally, the offer of genetic information that is unlikely to have much certainty or clinical value may create an inappropriate incentive for people to participate in research that they otherwise would not (15, 23).

For these reasons, we believe that gratitude is best expressed by provision of aggregate results. Participants volunteer to help generate the data needed to address the study’s research questions—the aggregate results—and informing them of these results expresses respect for them as persons as well as acknowledges their contribution to the study (15).

A special situation arises where advocacy organizations for rare disorders collaborate closely with researchers, providing an otherwise hard to come by scientific opportunity. As part of such endeavors, researchers and families can reach agreement during the study design phase about how results will be handled. However, many of the drawbacks of ‘gratitude’ still apply; the more powerful rationale for providing results in this situation is ‘degree of vulnerability’ (due to illness) and ‘depth of relationship.’

Degree of dependence

Participants may become dependent on researchers because they are impoverished, lack insurance, or join a trial because it is their last hope (16). Thus, researchers may be in a unique position to help participants.

Translating from the ancillary care framework (12), a key question for assessing dependence in genomic research is “How much difference would provision of individual genetic research results make to participants’ health?” In many cases, not revealing individual results would have no affect on participants’ well being because little is known about the clinical validity or utility of the results.

In some cases, however, researchers may be in a unique position to help because the genetic information is beneficial and other sources for obtaining it are limited. Health care providers’ preparedness to order and interpret genetic tests and to recommend appropriate follow-up care, as well as third-party reimbursement for these services remain substantial challenges (24). These issues of availability and access are features of the larger environment in which genomic research occurs, not of a study itself. However, researchers should monitor this evolving landscape and be aware of the extent to which it affects their study population’s ability to obtain needed genetic services. When results will be offered, participants must still understand that research analyses cannot be guaranteed to occur with the same timeliness as clinical testing.

These three factors—vulnerability, relationships, and dependence—influence the strength of the rationale for researchers’ obligations within the scope of entrustment. Because each of these factors can vary independently, obligations to offer individual results must be assessed for each study (Box 1). In evaluating researchers’ potential obligations, “strength of claim” factors must be weighed against the importance of reasons for not providing ancillary care (12). In some contexts, the rationale for providing individual results is insufficient to justify spending scarce research resources to do so.

Box 1. Examples of strength of claims for ancillary obligations in different research contexts.

Strong

Family-based studies for gene discovery or assessment of genotype-phenotype correlation

Research in collaboration with rare disease advocacy organizations

Community-based participatory research with disadvantaged populations

Moderate

Population-based biobanks designed to have ongoing interaction with participants (e.g., to collect additional biospecimens and information, for recontact about additional research, through newsletters intended to keep participants actively engaged)

Studies where participants are recruited through their source of health care, but without regard to disease status (i.e., they are not recruited specifically because they have been diagnosed with a condition of interest)

Weak

Secondary analysis of data shared from a repository under the control of a third party (not the researcher who originally collected the specimens and data)

Biobanks built using biospecimens leftover from clinical care and de-identified medical information

CONCLUSION

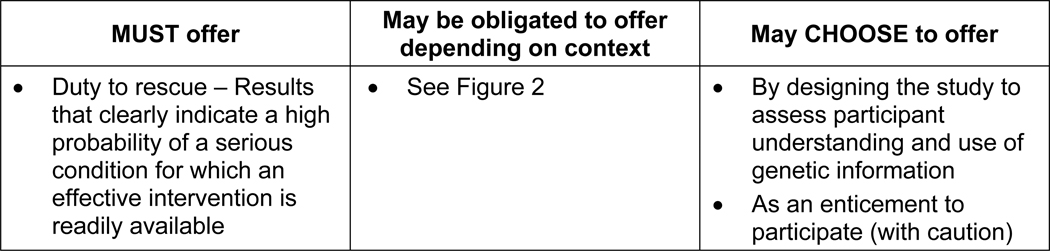

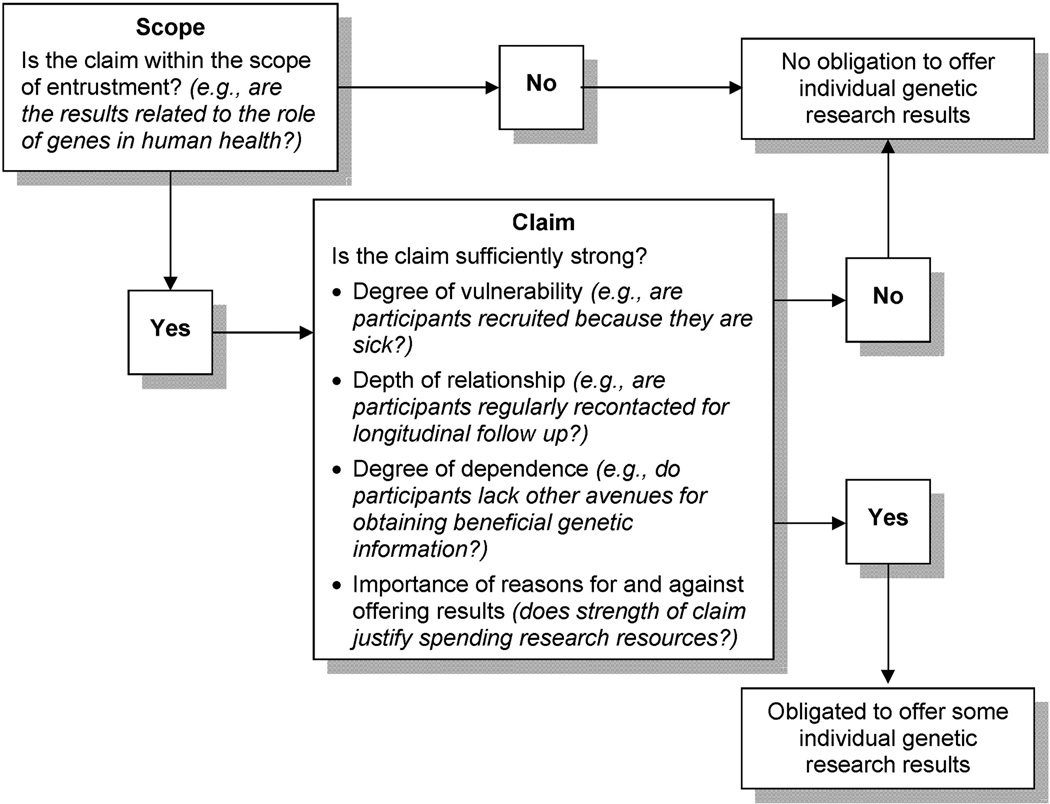

Debate over disclosure of individual genetic research results has stalled, in part because there is ample room for reasonable people to disagree about the value of various kinds of information. Research context is a vital element that has not been sufficiently incorporated into the discussion, and the concept of ‘ancillary care’ provides a useful framework for assessing the relationship between context and researchers’ potential obligations (Figures 1, 2).

Figure 1.

Researcher Obligations to Return Individual Results

Figure 2.

Framework for Evaluating Researcher Obligations *

*Adapted from Belsky & Richardson 2004

Our analysis suggests that, beyond the fundamental duty to rescue, a “one size fits all” threshold cannot be developed for decisions about return of individual results. Instead, researchers and IRBs must consider the scope of entrustment involved in the research, the intensity and duration of interactions with participants, and the vulnerability and dependence of the study population. The strength of this approach is that research context is foreseeable at the time a study is designed. Thus, the possibility of return of results can be planned and, importantly, included with more specificity in research budgets and informed consent processes.

As part of such planning, researchers and IRBs should try to anticipate the results likely to emerge, but—perhaps more so for current genetic research than for other types of research—many results cannot be foreseen. Professional judgment will always be required in determining whether to offer particular individual results. However, those decisions should be informed by the obligations that follow from different research contexts.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The development of this manuscript was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health Clinical and Translational Science Award 1UL1RR024128 to Duke University, and from the National Human Genome Research Institute Award 1P50HG003374 to the University of Washington.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kaufman D, Murphy J, Scott J, Hudson K. Subjects matter: a survey of public opinions about a large genetic cohort study. Genet Med. 2008;10:831–839. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e31818bb3ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wendler D, Emanuel E. The debate over research on stored biological samples: what do sources think? Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:1457–1462. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.13.1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kohane IS, Taylor PL. Multi-dimensional results reporting to participants in genomic studies: Getting the right message for the right person in the right way at the right time. Science Transl Med. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3000809. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beskow LM, Smolek SJ. Prospective biorepository participants' perspectives on access to research results. J Empir Res Hum Res Ethics. 2009;4:99–111. doi: 10.1525/jer.2009.4.3.99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ormond KE, Cirino AL, Helenowski IB, Chisholm RL, Wolf WA. Assessing the understanding of biobank participants. Am J Med Genet A. 2009;149A:188–198. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parker LS. The future of incidental findings: should they be viewed as benefits? J Law Med Ethics. 2008;36:341–351. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720X.2008.00278.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wolf SM, Lawrenz FP, Nelson CA, Kahn JP, Cho MK, Clayton EW, Fletcher JG, Georgieff MK, Hammerschmidt D, Hudson K, Illes J, Kapur V, Keane MA, Koenig BA, Leroy BS, McFarland EG, Paradise J, Parker LS, Terry SF, Van Ness B, Wilfond BS. Managing incidental findings in human subjects research: analysis and recommendations. J Law Med Ethics. 2008;36:219–248. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720X.2008.00266.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bookman EB, Langehorne AA, Eckfeldt JH, Glass KC, Jarvik GP, Klag M, Koski G, Motulsky A, Wilfond B, Manolio TA, Fabsitz RR, Luepker RV. NHLBI Working Group, Reporting genetic results in research studies: summary and recommendations of an NHLBI working group. Am J Med Genet A. 2006;140:1033–1040. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rothstein MA. Tiered disclosure options promote the autonomy and well-being of research subjects. Am J Bioeth. 2006;6:20–21. doi: 10.1080/15265160600934871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Joffe S, Miller FG. Bench to bedside: mapping the moral terrain of clinical research. Hastings Cent Rep. 2008;38:30–42. doi: 10.1353/hcr.2008.0019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith P. The duty to rescue and the slippery slope problem. Soc Theory Pract. 1990;16:19–41. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Richardson HS, Belsky L. The ancillary-care responsibilities of medical researchers. An ethical framework for thinking about the clinical care that researchers owe their subjects. Hastings Cent Rep. 2004;34:25–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Bioethics Advisory Commission, Research Involving Human Biological Materials: Ethical Issues and Policy Guidance. Volume 1. Rockville, MD: US Government Printing Office; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Greely HT. The uneasy ethical and legal underpinnings of large-scale genomic biobanks. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2007;8:343–364. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.7.080505.115721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Parker LS. Rethinking respect for persons enrolled in research. ASBH Exchange. 2006;9:1, 6–7. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Belsky L, Richardson HS. Medical researchers' ancillary clinical care responsibilities. BMJ. 2004;328:1494–1496. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7454.1494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.The Electronic Medical Records and Genomics (eMERGE) Network Consent & Community Consultation Workgroup Informed Consent Task Force. http://www.genome.gov/27526660.

- 18.Ravitsky V, Wilfond BS. Disclosing individual genetic results to research participants. Am J Bioeth. 2006;6:8–17. doi: 10.1080/15265160600934772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Christopher S, Watts V, McCormick AK, Young S. Building and maintaining trust in a community-based participatory research partnership. Am J Public Health. 2008;98:1398–1406. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.125757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.National Institutes of Health, Policy for Sharing of Data Obtained in NIH Supported or Conducted Genome-Wide Association Studies (GWAS) http://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/notice-files/NOT-OD-07-088.html.

- 21.Meltzer LA. Undesirable implications of disclosing individual genetic results to research participants. Am J Bioeth. 2006;6:28–30. doi: 10.1080/15265160600935811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Parker LS. Best laid plans for offering results go awry. Am J Bioeth. 2006;6:22–23. doi: 10.1080/15265160600934913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ossorio PN. Letting the gene out of the bottle: a comment on returning individual research results to participants. Am J Bioeth. 2006;6:24–25. doi: 10.1080/15265160600935555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Robson ME, Storm CD, Weitzel J, Wollins DS, Offit K. American Society of Clinical Oncology policy statement update: genetic and genomic testing for cancer susceptibility. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:893–901. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.0660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]