Abstract

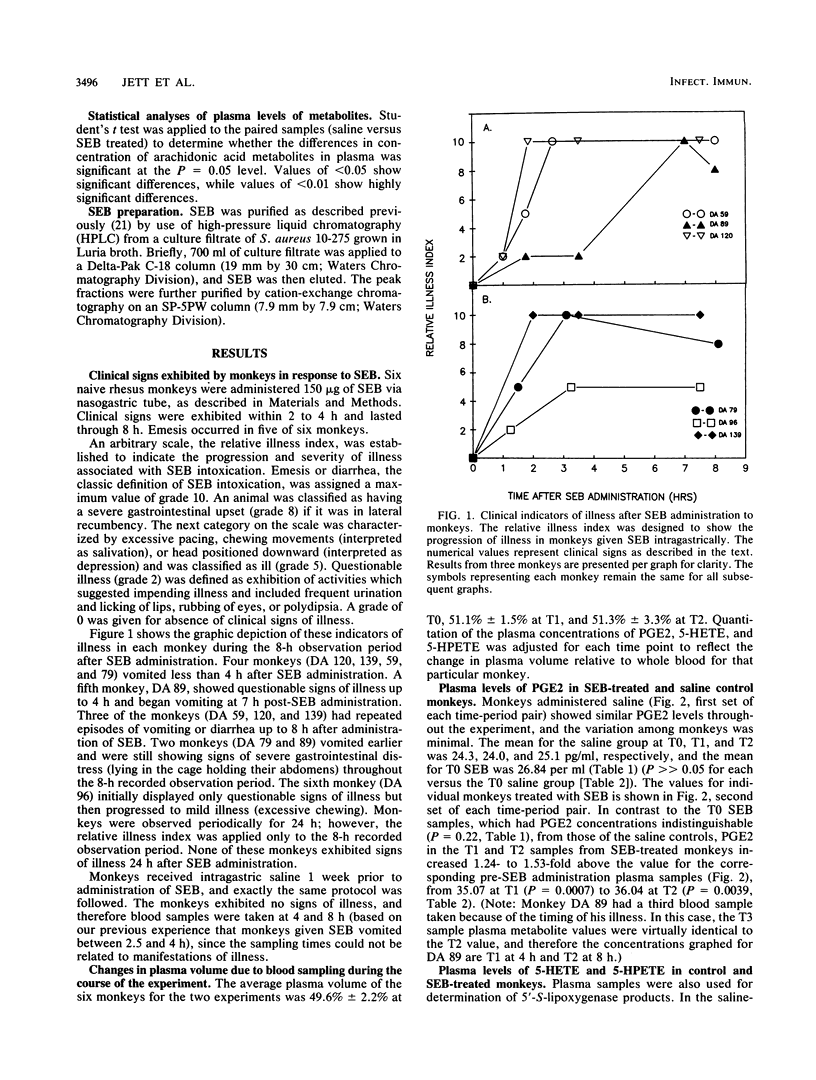

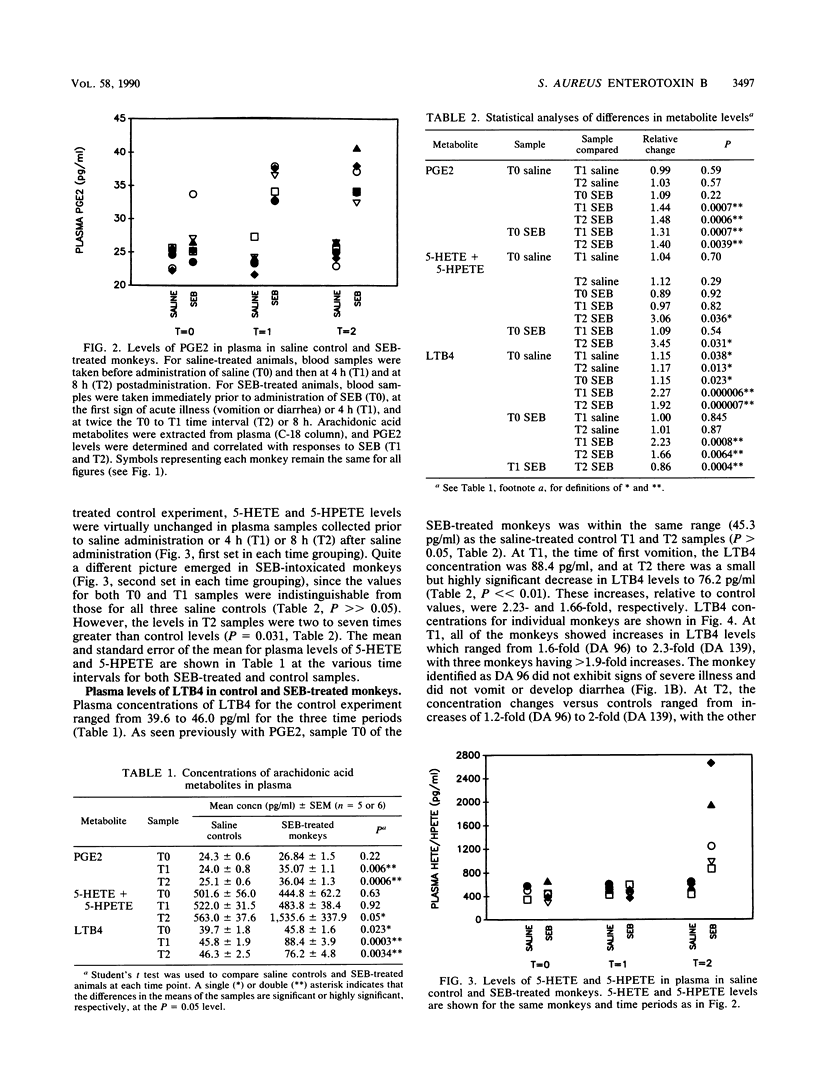

Arachidonic acid cascade products have been shown to be increased in vitro in Staphylococcus aureus enterotoxin B (SEB)-treated epithelial cell cultures in our laboratory. In order to confirm that these products were clinically related to SEB intoxication, monkeys were administered SEB by nasogastric intubation. It caused emesis in five of six monkeys (less than 4 h), and the sixth monkey showed signs of mild illness. The monkeys which vomited continued to display signs of gastrointestinal illness beyond 8 h but were without any apparent signs of illness by 24 h. Blood samples were collected prior to SEB administration, upon first indication of illness, and at twice that time interval. One week prior to SEB treatment, the same monkeys were administered saline by nasogastric intubation and in every way handled similarly in order to serve as their own controls. Blood samples were taken from the control animals at 0, 4, and 8 h. The plasma concentrations of prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), leukotriene B4 (LTB4), and 5-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid (5-HETE) did not vary significantly throughout the 8-h experiment for saline-treated controls, nor did they differ from the concentrations found in the plasma of monkeys just before administration of SEB. When the SEB-treated monkeys showed the first indication of illness (less than 4 h), the mean of the concentration in plasma of PGE2 increased 1.44-fold, that of LTB4 increased 2.23-fold, and that of 5-HETE was essentially unchanged. At twice the time interval of the first display of illness (less than 8 h), PGE2 was still elevated (1.48-fold), LTB4 had decreased slightly to 1.66-fold, and 5-HETE had soared (3,45-fold), suggesting a divergence in the enzymatic utilization of the parent compound of the latter two metabolites, 5-hydroperoxyeicosatetraenoic acid. These studies suggest that arachidonic acid cascade metabolites were a consequence of SEB intoxication and may provide a logical site for metabolic interference in SEB-induced toxicity.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Chesney P. J., Davis J. P., Purdy W. K., Wand P. J., Chesney R. W. Clinical manifestations of toxic shock syndrome. JAMA. 1981 Aug 14;246(7):741–748. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denzlinger C., Guhlmann A., Scheuber P. H., Wilker D., Hammer D. K., Keppler D. Metabolism and analysis of cysteinyl leukotrienes in the monkey. J Biol Chem. 1986 Nov 25;261(33):15601–15606. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donnelly R. P., Rogers T. J. Inhibitors of prostaglandin synthesis block the induction of staphylococcal enterotoxin B-activated T-suppressor cells. Cell Immunol. 1983 Oct 1;81(1):61–70. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(83)90211-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fast D. J., Schlievert P. M., Nelson R. D. Toxic shock syndrome-associated staphylococcal and streptococcal pyrogenic toxins are potent inducers of tumor necrosis factor production. Infect Immun. 1989 Jan;57(1):291–294. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.1.291-294.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson W. R., Jr Eicosanoids and lung inflammation. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1987 May;135(5):1176–1185. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1987.135.5.1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent T. H. Staphylococcal enterotoxin gastroenteritis in rhesus monkeys. Am J Pathol. 1966 Mar;48(3):387–407. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C. T., Griffin M. J., Hilmas D. E. Effect of staphylococcal enterotoxin B on cardiorenal functions and survival in X-irradiated rhesus macaques. Am J Vet Res. 1978 Jul;39(7):1213–1217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin T. R., Altman L. C., Albert R. K., Henderson W. R. Leukotriene B4 production by the human alveolar macrophage: a potential mechanism for amplifying inflammation in the lung. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1984 Jan;129(1):106–111. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1984.129.1.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin T. R., Pistorese B. P., Chi E. Y., Goodman R. B., Matthay M. A. Effects of leukotriene B4 in the human lung. Recruitment of neutrophils into the alveolar spaces without a change in protein permeability. J Clin Invest. 1989 Nov;84(5):1609–1619. doi: 10.1172/JCI114338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrill T. G., Sprinz H. The effect of staphylococcal enterotoxin on the fine structure of the monkey jejunum. Lab Invest. 1968 Feb;18(2):114–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morganroth M. L., Till G. O., Schoeneich S., Ward P. A. Eicosanoids are involved in the permeability changes but not the pulmonary hypertension after systemic activation of complement. Lab Invest. 1988 Mar;58(3):316–323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Needleman P., Turk J., Jakschik B. A., Morrison A. R., Lefkowith J. B. Arachidonic acid metabolism. Annu Rev Biochem. 1986;55:69–102. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.55.070186.000441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson J. W., Ochoa L. G. Role of prostaglandins and cAMP in the secretory effects of cholera toxin. Science. 1989 Aug 25;245(4920):857–859. doi: 10.1126/science.2549637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piper P. J. Formation and actions of leukotrienes. Physiol Rev. 1984 Apr;64(2):744–761. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1984.64.2.744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheuber P. H., Denzlinger C., Wilker D., Beck G., Keppler D., Hammer D. K. Cysteinyl leukotrienes as mediators of staphylococcal enterotoxin B in the monkey. Eur J Clin Invest. 1987 Oct;17(5):455–459. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.1987.tb01142.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheuber P. H., Denzlinger C., Wilker D., Beck G., Keppler D., Hammer D. K. Staphylococcal enterotoxin B as a nonimmunological mast cell stimulus in primates: the role of endogenous cysteinyl leukotrienes. Int Arch Allergy Appl Immunol. 1987;82(3-4):289–291. doi: 10.1159/000234209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeger W., Lasch H. G. Septic lung. Rev Infect Dis. 1987 Sep-Oct;9 (Suppl 5):S570–S579. doi: 10.1093/clinids/9.supplement_5.s570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soter N. A., Lewis R. A., Corey E. J., Austen K. F. Local effects of synthetic leukotrienes (LTC4, LTD4, LTE4, and LTB4) in human skin. J Invest Dermatol. 1983 Feb;80(2):115–119. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12531738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strickler M. P., Neill R. J., Stone M. J., Hunt R. E., Brinkley W., Gemski P. Rapid purification of staphylococcal enterotoxin B by high-pressure liquid chromatography. J Clin Microbiol. 1989 May;27(5):1031–1035. doi: 10.1128/jcm.27.5.1031-1035.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suttorp N., Seeger W., Zucker-Reimann J., Roka L., Bhakdi S. Mechanism of leukotriene generation in polymorphonuclear leukocytes by staphylococcal alpha-toxin. Infect Immun. 1987 Jan;55(1):104–110. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.1.104-110.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vroegop S. M., Buxser S. E. Cell surface molecules involved in early events in T-cell mitogenic stimulation by staphylococcal enterotoxins. Infect Immun. 1989 Jun;57(6):1816–1824. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.6.1816-1824.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weed L. A., Michael A. C., Harger R. N. Fatal Staphylococcus Intoxication from Goat Milk. Am J Public Health Nations Health. 1943 Nov;33(11):1314–1318. doi: 10.2105/ajph.33.11.1314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]