Abstract

Objective

To examine the association between self-reported physician-diagnosed arthritis and health-related quality of life among older Mexican Americans.

Design

Cross-sectional study involving population-based survey.

Setting

Hispanic Established Population for the Epidemiologic Study of the Elderly (EPESE) survey conducted in Texas, Arizona, New Mexico, Colorado, and California.

Participants

839 non-institutionalized Mexican American older adults (≥75 years) participating in Hispanic EPESE.

Main Outcome Measures

Self-reported physician-diagnosed arthritis; socio-demographic variables; medical conditions; body mass index (BMI); and the physical and mental composite scales from the Medical Outcomes Study Short Form 36 Health Survey (SF-36).

Results

518 (62%) of the subjects reported physician-diagnosed arthritis. Participants with arthritis had significantly lower scores on the physical composite scale (PCS) (mean = 35.3, SD = 11.3) and the mental composite scale (MCS) (mean = 53.5, SD = 10.8) of the SF-36 compared to persons without arthritis (PCS mean = 42.9, SD = 10.9; MCS mean = 57.0, SD = 8.8). Multiple regression showed that arthritis was associated with decreased PCS and MCS (model estimates of -5.74 [SE = 0.83]; and -3.16 [SE = 0.64]), respectively, after controlling for sociodemographic and clinical covariates.

Conclusions

Arthritis is a highly prevalent medical condition in Mexican American older adults. Our findings suggest that deficits in both physical health and mental function contribute to reduced quality-of-life in this population.

Keywords: aging, disability, life satisfaction

Introduction

By 2030, it is estimated that the number of Americans aged 65 and older will be 20% of the population.1-3 Nearly 80% of older Americans are living with at least one chronic condition4-6 with arthritis being the most common cause of disability in the U.S.7-11 affecting 47% of persons >65 years.12 The prevalence of arthritis is projected to increase by 40% as the median age of the U.S. population increases over the next 25 years.13 There are 750,000 hospitalizations14 and 36 million outpatient visits annually attributed to arthritis.15 Direct medical costs for arthritis were $81 billion in 2003, up from $51 billion in 1997.16

Arthritis affects the older Hispanic population more than any other race/ethnic group.8,9,17 Data from the Asset and Health Dynamic Survey Among the Oldest Old (AHEAD)17 reported the adjusted prevalence of arthritis was 52% in older Hispanics; 47% in older non-Hispanic blacks, and 32% in older non-Hispanic whites. Greater than 65% of the Hispanic population in the U.S. are Mexican American and it is the fastest growing segment of the population over 65 years of age.8-9

The symptoms and consequences of arthritis often result in limitations in functional capacity and the ability to perform activities of daily living,18-21 severe pain,22 psychological distress,23 and depression.24 One health outcome of primary interest in patients with arthritis is health-related quality of life. Arthritis can affect several of the physical and psychological health domains. A number of large population-based studies have examined the effects of arthritis on disability and physical function,18-21 but few have assessed overall health-related quality of life.25-30 Several instruments, such as the Arthritis Impact Measurement Scales (AIMS/AIMS2), Disease Repercussion Profile (DRP), the Rheumatoid Arthritis Quality of Life (RAQOL), and the Medical Outcomes Study Short Form 36 Health Survey (SF-36), have been used in patients with arthritis to measure health-related quality of life.31

Studies examining older adults with arthritis have revealed lower summary values compared to older persons without arthritis, as measured by either the SF-3623,25, or the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) quality of life measure.27-30, 32-33 Little is known, however, about the effect of arthritis on health-related quality of life in older Mexican Americans.8

We examined the association between health-related quality of life in a sample of older Mexican Americans (≥75 years) with and without arthritis. We used the SF-36, which defines health-related quality of life as “an individual's or group's perceived physical and mental health over time.”34 We selected the SF-36 because it is widely used to assess health-related quality of life and has been validated for this sample of older Mexican Americans.35 We hypothesized that the presence of arthritis would be associated with a low level of physical health in older Mexican Americans after controlling for demographic and clinical covariates.

Methods

Data sources

Data were from the Hispanic Established Population for Epidemiological Study of the Elderly (EPESE).36-38 The Hispanic EPESE is a population-based study that included 3,050 non-institutionalized Mexican Americans aged 65 years at baseline (1993-4). Participants were from Arizona, California, Colorado, New Mexico, and Texas. The total sample has been described in detail elsewhere.36-38 We examined 839 participants in the Hispanic aged ≥75 years who were enrolled in a sub-study of frailty. The participants included persons able to complete the physical performance measures required for the frailty study (e.g., grip strength, walking speed) and who responded to all questions in the SF-36. All participants were examined in their homes by trained interviewers. The interviewers received 30 hours of instruction on performance‐based assessments of physical function including balance, gait, and assessment of daily living skills. The interviews were conducted in Spanish or English, depending on the respondent's preference. Detailed information on the data collection protocol is provided in previous publications.36-38 The Hispanic EPESE data, questionnaires, and protocol instructions are available as public use data files at: http://www.icpsr.umich.edu/icpsrweb/ICPSR/studies/2851.

Data for the current study were collected in 2006.

Measurements

Arthritis

A prior physician diagnosis of arthritis was assessed with the question: “Has a doctor ever told you that you have arthritis or rheumatism?” Similar questions have been used in other national surveys39 and epidemiological studies6 with adequate sensitivity and specificity.10

Outcome measures (Health-Related Quality of Life)

The Short-Form 36-item Health Survey (SF-36) is a widely used measure of self-reported health-related quality of life.33,40 The SF-36 consists of 36 items covering 8 domains assessing the subject's physical and mental status. The Physical Composite Scale (PCS) includes the following domains: physical functioning (PF) (10 items); role limitations due to physical functioning (RP) (4 items); bodily pain (BP) (2 items); and general health (GH) (5 items). The Mental Composite Scale (MCS) includes the domains of general mental health (MH) (5 items); role limitations due to emotional problems (RE) (3 items); social functioning (SF) (2 items); and vitality (VT) (4 items).

The PCS and MCS scores range from 0 to 100, with higher values reflecting better health-related quality of life.33,41 Both the PCS and MCS have demonstrated good discriminate validity for identifying differences between clinically meaningful groups.41 The minimum clinically important differences (MCID) for arthritic conditions range between 2.5 to 5 points for both composite scores.42-44 The Cronbach's alpha for the SF-36 domains as administered in our sample ranged from 0.76 to 0.96.

Covariates

Sociodemographic characteristics included age (continuous), gender, formal years of education (continuous), and current marital status (i.e.; married or unmarried: single/divorced/widow). Body mass index (BMI) was calculated in the standard manner by dividing weight in kilograms by height in meters squared. We assessed the presence of medical conditions by asking the respondents if they had ever been told by a doctor that they had a heart attack, stroke, hypertension, diabetes and/or osteoporosis.

Statistical Analysis

We examined all variables using descriptive and univariate statistics for continuous variables and Chi-square for categorical variables. Multivariable linear regression models were computed to predict the PCS and MCS scores. To investigate the association between arthritis and the SF-36 physical and mental composite scales, we computed 3 models for both outcomes. Model 1 examined the unadjusted relation between arthritis and the SF-36 composite scores. In model 2, we investigated whether the association between arthritis and PCS or MCS was affected by sociodemographic variables (age, gender, education, and marital status). In model 3, BMI and all other medical conditions were included, along with the variables in model 2. The assumptions of linearity, normality, collinearity, and goodness-of-fit were tested and met for each model. All analyses were performed using the SAS, version 9.1.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

The descriptive statistics for the sample, based on the presence or absence of arthritis, are shown in Table 1. Five-hundred eighteen (62%) of the 839 participants reported doctor-diagnosed arthritis. Participants with arthritis were more likely to be unmarried women, have a lower educational level, and a higher BMI than persons without arthritis. They were also more likely to report hypertension and osteoporosis.

Table 1. Sociodemographic and Health-Related Characteristics for the Entire Sample and for Persons with and without self-reported physician-diagnosed arthritis.

| Total | No self-reported diagnosed arthritis | Self-reported physician-diagnosed arthritis | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | N = 839 | N = 321 | N = 518 |

| Sex† (women) | 538 (64.1%) | 175 (54.5%) | 363 (70.1%) |

| Married† (yes) | 344 (41.0%) | 151 (47.0%) | 193 (37.2%) |

| Heart Attack | 143 (17.0%) | 51 (16.0%) | 92 (17.7%) |

| Hypertension† | 557 (66.4%) | 189 (58.9%) | 368 (71.0%) |

| Diabetes | 270 (32.2%) | 96 (29.9%) | 174 (33.6%) |

| Osteoporosis† | 196 (23.3%) | 44 (13.7%) | 152 (29.3%) |

| Stroke | 107 (12.7%) | 39 (12.1%) | 68 (13.1%) |

| Characteristics Mean (SD) | |||

| Age in yrs | 82.1 (4.5) | 82.6 (4.1) | 81.7 (4.2) |

| Education yrs‡ | 5.07 (3.9) | 4.98 (3.7) | 4.53 (3.6) |

| BMI in kg/m2† | 27.3 (5.1) | 25.8 (4.3) | 27.5 (4.9) |

| SF=36 | |||

p<.0001,

p <.001,

p < .05: independent t-test and chi-square analyses for unadjusted comparisons between arthritis and no arthritis groups.

SD = Standard Deviation, BMI = Body Mass Index

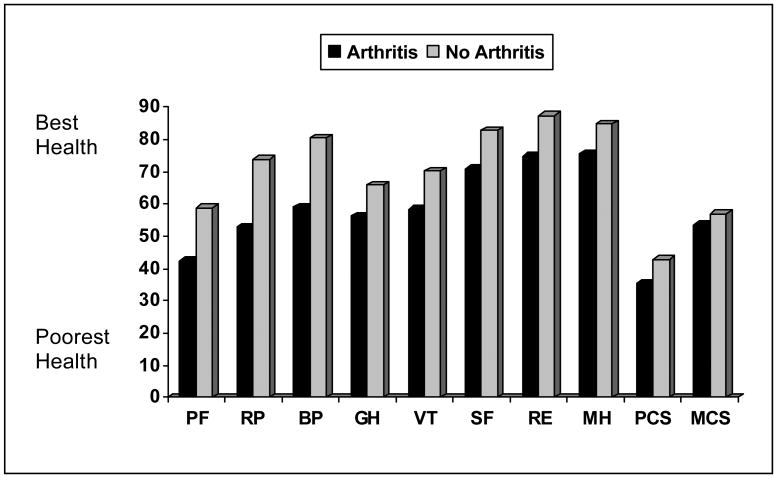

Figure 1 displays domain and composite scores for older Mexican Americans with arthritis and without arthritis. Older Mexican Americans with arthritis were significantly more likely to report low health-related quality of life in all 8 domains of the SF-36 compared to those without arthritis. The PCS and MCS means (SDs) in persons with arthritis were 35.3 (11.3), and 53.5 (10.8), respectively.

Figure 1. Comparison of mean SF-36 scores between older Mexican Americans with and without self-reported physician-diagnosed arthritis (aged 75+).

PF = physical functioning, RP = role limitations due to physical functioning, BP = bodily pain, GH = general health, VT = vitality, SF = social functioning, RE = role limitations due to emotional problems, MH = mental health, PCS = standardized physical composite scale, MCS = standardized mental composite scale.

In model 1, arthritis was significantly associated with a decrease of -7.58 (SE = 0.79) points on the PCS score (see Table 2). In model 2, when sociodemographic variables (age, sex, education, and marital status) were added, the association decreased but remained statistically significant. In model 3, after controlling for BMI and medical conditions along with the variables in model 2, the association with arthritis was attenuated by approximately 23% [(7.58 – 5.74)/7.58 = 0.235], but remained strong at -5.74. Entering all covariates in the model resulted in an increase of explained variance from an R2 of 0.09 to 0.21. Other variables significantly associated with the physical aspects of health-related quality of life were age, gender, education, BMI, diabetes, heart attack, osteoporosis, and stroke (see Table 2).

Table 2. Regression Analysis of self-reported physician-diagnosed arthritis on the Physical Composite Scale (PCS); (N=839).

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | (SE) | P-value | b | (SE) | P-value | b | (SE) | P-value | |

| Arthritis | -7.58 | (0.79) | <.0001 | -6.80 | (0.78) | <.0001 | -5.74 | (0.83) | <.0001 |

| Age (years) | -0.28 | (0.08) | <.001 | -0.34 | (0.12) | <.0001 | |||

| Sex (Female) | -3.77 | (0.86) | <.0001 | -2.58 | (0.93) | <.01 | |||

| Education | 0.34 | (0.09) | <.001 | 0.32 | (0.15) | <.001 | |||

| Married | -0.02 | (0.85) | 0.98 | 0.23 | (0.87) | 0.77 | |||

| BMI | -0.17 | (0.15) | 0.03 | ||||||

| Hypertension | -0.15 | (0.84) | 0.85 | ||||||

| Diabetes | -2.31 | (0.82) | <.01 | ||||||

| Heart attack | -3.69 | (1.01) | <.001 | ||||||

| Osteoporosis | -4.84 | (0.92) | <.0001 | ||||||

| Stroke | -2.31 | (1.16) | 0.04 | ||||||

| R2 | 0.09 | 0.14 | 0.21 | ||||||

b = parameter estimate, SE = standard error, BMI = body mass index

Model 1 included only arthritis

Model 2, included age, gender, education, and marital status along with arthritis

Model 3, included medical conditions (hypertension, diabetes, heart attack, osteoporosis, and stroke) along with variables in Model 2

Table 3 presents the regression models for the MCS of the SF-36. Among older Mexican Americans, arthritis was associated with a decrease in MCS of -3.48 (SE = 0.71) points. After controlling for covariates (models 3), arthritis was still significantly associated with decreased mental composite scores (b =-3.16 [SE = 0.64]). The pattern of covariates significantly associated with the mental aspects of health-related quality of life was different than for the PCS and included diabetes and heart attack.

Table 3. Regression Analysis of self-reported physician-diagnosed arthritis on the Mental Composite Scale (MCS); (N=839).

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | (SE) | P-value | b | (SE) | P-value | b | (SE) | P-value | |

| Arthritis | -3.48 | (0.71) | <.0001 | -3.28 | (0.72) | <.0001 | -3.16 | (0.64) | <.0001 |

| Age (years) | 0.13 | (0.08) | 0.11 | 0.15 | (0.07) | 0.07 | |||

| Sex (Female) | -1.21 | (0.79) | 0.13 | -1.01 | (0.77) | 0.22 | |||

| Education | 0.14 | (0.09) | 0.13 | 0.15 | (0.07) | 0.10 | |||

| Married | -0.61 | (0.78) | 0.43 | -0.49 | (0.79) | 0.53 | |||

| BMI | 0.1 | (0.06) | 0.15 | ||||||

| Hypertension | 0.03 | (0.81) | 0.97 | ||||||

| Diabetes | -1.94 | (0.76) | 0.01 | ||||||

| Heart attack | -2.43 | (1.03) | 0.01 | ||||||

| Osteoporosis | -1.16 | (0.92) | 0.18 | ||||||

| Stroke | -1.24 | (1.10) | 0.25 | ||||||

| R2 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.06 | ||||||

b = parameter estimate, SE = standard error, BMI = body mass index

Model 1 included only arthritis

Model 2, included age, gender, education, and marital status along with arthritis

Model 3, included medical conditions (hypertension, diabetes, heart attack, osteoporosis, and stroke) along with variables in Model 2

Discussion

The aim of the current study was to examine the association between arthritis and health-related quality of life among Mexican American adults aged 75 years and older. Our findings can be summarized as follows: self-reported physician-diagnosed arthritis was significantly associated with decreased scores in the physical (PCS) and mental composite (MCS) scales of the SF-36. The effect was stronger for the PCS.

The prevalence of arthritis was nearly 62% among older (≥75 years) Mexican Americans. This rate is higher compared to 25% to 50% reported in the literature for the general population, suggesting an escalating prevalence of arthritis with age in this sample of Mexican American older adults.17,45 The current results extend a prior trend reported from Hispanic EPESE data; the prevalence of arthritis in participants aged ≥65 years was 41%, and it increased to more than 55% for those >70 years of age.46

We found that older Mexican Americans with arthritis scored lower on scales that measured physical health compared to participants without arthritis. As expected, given the pathophysiology of osteoarthritis and its association with physical disability, our findings suggest a negative impact on physical aspects of health-related quality of life. According to data from the National Survey of Functional Health Status,34 patients with arthritis scored significantly lower on the PCS only, indicating that the impact of arthritis was primarily on physical health.

In our data, Mexican Americans with arthritis had lower MCS scores compared to participants without arthritis. The arthritis-related differences in MCS scores suggest that the disease impacted areas beyond physical function in our sample. Although a direct link between arthritis and mental aspects of health-related quality of life is not obvious, previous research has shown adverse effects of arthritis across dimensions of health-related quality of life, including mental health.27,30 For example, Hill et al.47 found that persons with self-reported physician-diagnosed arthritis have more mental health comorbid conditions and are at greater risk for anxiety and depression compared to persons without arthritis. They suggest that coexisting psychological distress compounds the inherent negative consequences of arthritis for many individuals.47 This is a topic that requires further investigation.

Cultural factors, such as individual versus family orientation, attitudes toward work, illness, and health beliefs, may influence health-related quality of life in patients with arthritis.24,48 For example, Escalante et al. 24 found that Hispanic patients with rheumatoid arthritis, who are not fully acculturated to the mainstream Anglo society, had more depressive symptoms and psychological distress than did Non-Hispanic patients. Fisher et al. 49 found that older Mexican Americans with arthritis, who had a high positive affect, had a lower incidence of disability.

Our study has several limitations. Since data were examined cross-sectionally, the association between arthritis and health-related quality of life cannot be viewed as causal. Longitudinal studies are needed to examine predictive relationships between arthritis and health-related quality of life ratings with other factors, such as depression and pain. Another limitation of our study was that it relied on self-report of physician diagnosed arthritis. Some participants might have had arthritis, but were not diagnosed at the time of interview and, therefore, misclassified. Self-report of physician diagnosis of arthritis has been used in other national surveys39,50 and has demonstrated good concurrent reliability with medical records and acceptable sensitivity and specificity.10

Our investigation has several strengths, including a large community-based sample of Mexican Americans older adults. We also used a widely accepted and validated measure to assess health-related quality of life – the SF-36. Information was collected in the participants' homes by trained interviewers and the respondents were given the option to complete the interview and assessment in English or Spanish.

A better understanding of the relation between arthritis and health-related quality of life is necessary to develop effective prevention and treatment programs, particularly for older adults.51 For example, if future research confirms that older Mexican Americans with arthritis display both reduced physical capacity and impaired mental function compared to persons without arthritis; then attention should be devoted to the types of educational and training materials prepared for this population, which could aid them in managing their health and maintaining their independence. This is particularly important for Mexican Americans; some of whom will require information in a bilingual format.52 In addition, state health departments that organize physical activity programs, such as the “Buenos Días, Artritis,”53 should consider the implications of the current findings related to both physical and mental functioning in planning activities and education/training materials.

In conclusion, we found arthritis to be highly prevalent in this sample of older Mexican Americans, and that persons with arthritis demonstrated poor health-related quality of life compared to those without arthritis. Arthritis was significantly associated with both low physical and mental components of health-related quality of life, even after adjusting for sociodemographic and clinical covariates. Future population-based longitudinal research is necessary in order to examine how health-related quality of life changes over time and the relation to physical activity, pain and mental function.53 This research is particularly important in underserved groups, such as Mexican American older adults, who are at high risk for arthritis.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institute on Aging - R01 AG017638 (Ottenbacher) and R01 AG010939 (Markides). Dr. Al Snih was supported by a career development grant, K12 HD052023 (PI: Berenson), funded by the National Institute of Child Health & Human Development. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not represent the official views of the institutes above. There are no financial benefits to the authors.

References

- 1.U.S. Census Bureau . Population Projections Program. Population Division, U.S. Census Bureau; Washington, D.C.: 2000. Population Projections of US by Age, Sex, Race, Hispanic Origin, and Nativity: 1999 to 2100. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), The Merck Company Foundation . The State of Aging and Health in America 2007. The Merck Company Foundation; Whitehouse Station, NJ: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hobbs FB, Damon BL. 65+ in the United States: Current Population Reports: 1996. U.S. Government Printing Office; Washington, DC: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 4.DeFrances C, Cullen K, Kozak L. National Hospital Discharge Survey: 2005 Annual Summary with Detailed Diagnosis and Procedure Data. National Center for Health Statistics; Hyattsville, MD: 2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Amador L, Loera J. Preventing postoperative falls in the older adult. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;204:447–453. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2006.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martin L, Soldo B. Racial and Ethnic Differences in the Health of Older Americans. National Academy Press; Washington, DC: 1997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Federal Interagency Forum on Aging-Related Statistics . Older Americans 2008: Key Indicators of Well-Being (Older Americans 2008) U.S. Government Printing Office; Washington, DC: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guzman B. The Hispanic Population: Census 2000 Brief. US Dept. of Commerce, Bureau of the Census; Washington, DC: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. Vol. 50. 2001. Prevalence of disabilities and associated health conditions among adults--United States, 1999; pp. 120–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Helmick C, Felson D, Lawrence R, et al. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States. Part I. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:15–25. doi: 10.1002/art.23177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ostir GV, Ottenbacher KJ, Markides KS. Onset of frailty in older adults and the protective role of positive affect. Psych Aging. 2004;19:402–408. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.19.3.402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fried LP. Epidemiology of aging. Epidemiol Rev. 2001;22:95–106. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a018031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hootman J, Helmick C. Projections of US prevalence of arthritis and associated activity limitations. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:226–229. doi: 10.1002/art.21562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lethbridge-Cejku M, Helmick C, Popovic J. Hospitalizations for arthritis and other rheumatic conditions: data from the 1997 National Hospital Discharge Survey. Med Care. 2003;41:1367–1373. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000100582.52451.AC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hootman J, Helmick C, Schappert S. Magnitude and characteristics of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions on ambulatory medical care visits, United States, 1997. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;47:571–581. doi: 10.1002/art.10791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yelin E, Murphy L, Cisternas MG, et al. Medical care expenditures and earnings losses among persons with arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in 2003, and comparisons with 1997. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:1397–1407. doi: 10.1002/art.22565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dunlop D, Manheim L, Song J, et al. Arthritis prevalence and activity limitations in older adults. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44:212–221. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200101)44:1<212::AID-ANR28>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Song J, Chang RW, Dunlop DD. Population impact of arthritis on disability in older adults. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;55:248–55. doi: 10.1002/art.21842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Covinsky KE, Lindquist K, Dunlop DD, et al. Effect of arthritis in middle age on older-age functioning. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:23–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01511.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Song J, Chang HJ, Tirodkar M, et al. Racial/ethnic differences in activities of daily living disability in older adults with arthritis: a longitudinal study. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57:1058–1066. doi: 10.1002/art.22906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Al Snih S, Markides KS, Ostir GV, Goodwin JS. Impact of arthritis on disability among older Mexican Americans. Ethnicity Dis. 2001;11:19–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Paananen M, Taimela S, Auvinen J, et al. Impact of Self-Reported Musculoskeletal Pain on Health-Related Quality of Life among Young Adults. Pain Med. 2011;12:9–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2010.01029.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hill CL, Parsons J, Taylor AW, et al. Health related quality of life in a population sample with arthritis. J Rheumatol. 1999;26:2029–2035. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Escalante A, del Rincón I, Mulrow CD. Symptoms of depression and psychological distress among Hispanics with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res. 2000;13:156–167. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200006)13:3<156::aid-anr5>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alonso J, Ferrer M, Gandek B, et al. Health-related quality of life associated with chronic conditions in eight countries: results from the International Quality of Life Assessment (IQOLA) Project. Qual Life Res. 2004;13:283–298. doi: 10.1023/b:qure.0000018472.46236.05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mili F, Helmick C, Moriarty D. Health related quality of life among adults reporting arthritis: analysis of data from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, US, 1996-99. J Rheumatol. 2003;30:160–166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kovac S, Mikuls T, Mudano A, et al. Health-related quality of life among self-reported arthritis sufferers: effects of race/ethnicity and residence. Qual Life Res. 2006;15:451–460. doi: 10.1007/s11136-005-3213-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. Vol. 49. 2000. Health-related quality of life among adults with arthritis--behavioral risk factor surveillance system, 11 states, 1996-1998; pp. 366–369. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dominick K, Ahern F, Gold C, et al. Health-related quality of life among older adults with arthritis. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2004;2:5. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-2-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carr A. Arthritis Rheum. Vol. 49. 2003. The Arthritis Impact Measurement Scales (AIMS/AIMS2), Disease Repercussion Profile (DRP), EuroQoL, Nottingham Health Profile (NHP), Patient Generated Index (PGI), Quality of Well-Being Scale (QWB), RAQoL, Short Form-36 (SF-36), Sickness Impact Profile (SIP), SIP-RA, and World Health Organization's Quality of Life Instruments (WHOQoL, WHOQoL-100, WHOQoL-Bref) pp. S113–S133. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mielenz T, Jackson E, Currey S, et al. Health Qual Life Outcomes. Vol. 4. 2006. Psychometric properties of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Health-Related Quality of Life (CDC HRQOL) items in adults with arthritis; p. 66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Measuring Healthy Days Monograph. CDC; Atlanta, GA: 2000. p. 8. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kosinski M, Keller S, Ware JJ, et al. The SF-36 Health Survey as a generic outcome measure in clinical trials of patients with osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis: relative validity of scales in relation to clinical measures of arthritis severity. Med Care. 1999;37:MS23–39. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199905001-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Peek MK, Ray L, Patel K, et al. Reliability and validity of the SF-36 among older Mexican Americans. Gerontologist. 2004;44:418–425. doi: 10.1093/geront/44.3.418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Markides KS, Stroup-Benham CA, Goodwin JS, et al. The effect of medical conditions on the functional limitations of Mexican-American elderly. Ann Epidemiol. 1996;6:386–391. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(96)00061-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Markides K, Rudkin L, Angel R, et al. Health Status of Hispanic Elderly. In: Martin LG, Soldo BJ, editors. Racial and Ethnic Differences in the Health of Older Americans. National Academy Press; Washington, DC: 1997. pp. 285–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Markides K, Stroup-Benham C, Black S, et al. The health of Mexican American elderly selected findings from the Hispanic EPESE. In: Wykle M, Ford A, editors. Serving minority elders in the 21st century. Springer; New York: 1999. pp. 72–90. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miles TP, Flegal K, Harris T. Musculoskeletal disorders: time trends, comorbid conditions, self-assessed health status, and associated activity limitations. Vital Health Stat. 1994;3:275–288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vetter T. A primer on health-related quality of life in chronic pain medicine. Anesth Analg. 2007;104:703–718. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000255290.64837.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ware JE, Kosinski M, Keller SK. SF-36 Physical and Mental Health Summary Scales: A User's Manual. The Health Institute; Boston, MA: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Khanna D, Tsevat J. Health-related quality of life--an introduction. Am J Manag Care. 2007;9 13:S218–223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Graham JE, Stoebner-May DG, Ostir GV, et al. Health related quality of life in older Mexican Americans with diabetes: a cross-sectional study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2007;5:39. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-5-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ware J, Snow K, Kosinski M, et al. SF-36 Health Survey manual and interpretation guide. The Health Institute, New England Medical Center; Boston: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Center for Disease Control and Prevention Prevalence of doctor-diagnosed and arthritis-attributable activity limitation. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59(39) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Al Snih S, Markides KS, Ray L, et al. Prevalence of arthritis in older Mexican Americans. Arthritis Care Res. 2000;13:409–416. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200012)13:6<409::aid-art12>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hill CL, Gill T, Taylor AW, et al. Psychological factors and quality of life in arthritis: a population-based study. Clinic Rheum. 2007;26:1049–1054. doi: 10.1007/s10067-006-0439-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Escalante A, Del Rincón I. The disablement process in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;47:333–342. doi: 10.1002/art.10418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fisher MN, Al Snih S, Ostir GV, Goodwin JS. Positive affect and disability among older Mexican American with arthritis. Arthritis Care Res. 2004;51:34–39. doi: 10.1002/art.20079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. Atlanta, GA: 2006. Prevalence of Doctor-Diagnosed Arthritis and Arthritis-Attributable Activity Limitation, United States 2003-2005; pp. 1089–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Singh JA, Nelson DB, Fink HA, Nichol KL. Health-related quality of life predicts future health care utilization and mortality in veterans with self-reported physician-diagnosed arthritis: the veteran's arthritis quality of life study. Sem Arth Rheum. 2005;34(5):755–765. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2004.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.US Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) Healthy People 2010: Understanding and Improving Health. U.S. Government Printing Office; Washington, DC: 2001. Arthritis, Osteoporosis, and Chronic Back Conditions. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Arthritis Foundation, Association of State and Territorial Health Officials, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . National Arthritis Action Plan: A Public Health Strategy. Arthritis Foundation; Atlanta, GA: 1999. [Google Scholar]