Abstract

Obesity in humans is a complex polygenic trait with high inter-individual heritability estimated at 40–70%. Candidate gene, DNA linkage and genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have allowed for the identification of a large set of genes and genomic regions associated with obesity. Structural chromosome abnormalities usually result in congenital anomalies, growth retardation and developmental delay. Occasionally, they are associated with hyperphagia and obesity rather than growth delay. We report four new individuals with structural chromosome abnormalities involving 10q22.3-23.2, 16p11.2 and Xq27.1-q28 chromosomal regions with early childhood obesity and developmental delay. We also searched and summarized the literature for structural chromosome abnormalities reported in association with childhood obesity.

Keywords: Obesity, aCGH, chromosome, deletion, duplication, translocation, fluorescent in situ hybridization, CNV.

INTRODUCTION

Obesity is a major growing health problem facing children and adults worldwide and particularly in the Westernized world. It represents an energy imbalance in which energy intake exceeds expenditure. While decreased physical activity and increased caloric intake are the major forces behind this epidemic, there is strong evidence supporting the role of major genes and minor genomic variants in causing or contributing to human obesity. Various genetic techniques had been used to identify the genetic basis of severe early childhood obesity and with the more common forms of obesity usually seen in older individuals. To date, cytogenetic studies followed by appropriate molecular analysis in a small group of children with severe childhood obesity have shown specific structural chromosome abnormalities. Large cohorts of obese adults have also been studied using genome-wide linkage and association scans. In most of these studies, single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) based platforms were used rather than copy number variants. Beginning in 1996, the “Human Obesity Gene Map” provided a catalogue of all known genetic variants and chromosomal loci associated with or linked to obesity-related traits [1]. The most recent update was published in 2006 [2] and included 176 single-gene mutations in 11 different genes, 50 loci related to known Mendelian syndromes, 244 murine adiposity related genes, 408 animal model based quantitative trait loci (QTLs) and 253 human QTLs from 61 genome-wide scans.

In this report, we present our experience in a small series of individuals with childhood obesity and other health problems presenting for genetic services. Four individuals with obesity and other health problems were found to have structural chromosome abnormalities. We briefly review structural chromosome abnormalities associated with obesity reported in the literature.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

Clinical Reports

Subject 1

At 34 years of age, this woman (Fig. 1a,1b) presented with obesity since early childhood and developed idiopathic urticaria which became prednisone dependent. Therefore, multiple hives and target lesions were noted.

Fig. (1).

Photographs of Subjects 1-4. Subject 1 (a,b) has synophrys, obesity and urticaria (not shown). Subject 2 (c,d) and his sister, Subject 3 (e) have a prominent forehead, bulky ears, micrognathia and full lips. Subject 4 (f,g) has myopathic facies, ptosis, long and narrow face, truncal obesity, a prominent forehead and prognathism.

She was diagnosed with endometriosis at 22 years of age and a large lipoma on her upper back required resection at 34 years of age. She had recurrent facial methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infection and poison ivy. She had no cognitive abnormalities. An abdominal CT scan performed at 35 years of age showed a normal gastrointestinal tract but unexpectedly marked atrophy of the right kidney was seen with bilateral renal focal clubbing and cortical scarring. Calcified renal cysts were also noted in the right kidney. Extensive laboratory workup (rheumatoid factor, aldosterone, cortisol, FSH/LH, insulin, testosterone, celiac disease antibody panel, Hepatitis B antibody profile, ferritin, H. pylori profile, serum protein electrophoresis, thyroid peroxidase antibody, anti-thyroglobulins and histamine and tryptase levels) were all within normal range. Her serum uric acid was mildly increased and an ANA screen was positive at a low titer (1 in 40, speckled pattern). Her weight was 133.36 kg (>95th centile), height was 155 cm and BMI was 55.5 kg/m2. She had synophrys, a “buffalo hump” fat pattern and a recurring large lipoma on her upper back region.

A 105K-whole-genome array comparative genomic hybridization (aCGH) study revealed a 7.8 Mb duplication at chromosome 10q22.3-q23.2 (Fig. 2a) (base position: 81,281,895-89, 091,213; hg18) which was absent in her mother. Her father was not available for evaluation. The duplication was confirmed by fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) using the BAC clone “RP11-830JJ13” (Fig. 3a).

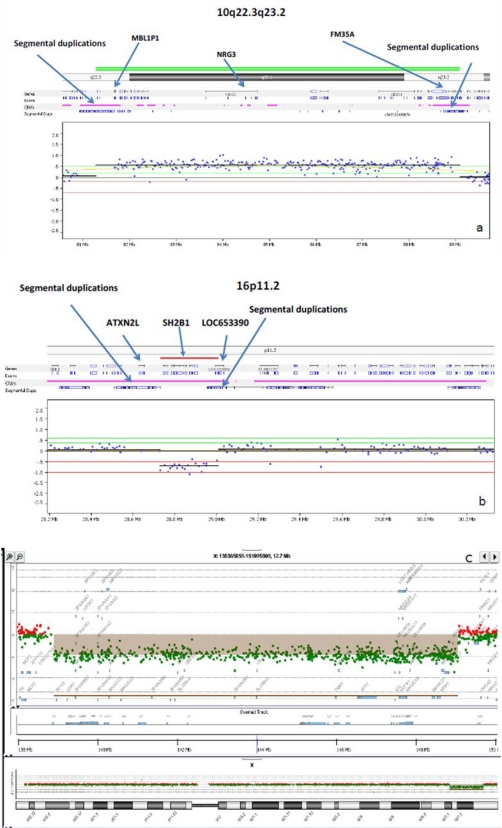

Fig. (2).

Array CGH (log2 R) profiles for Subjects 1-4. Subject 1(a) has a large 7.8 Mb duplication found at 10q22.3-q23.2 between the segmental LCR3 and LCR4 regions (arrows). Subjects 2 and 3 (b) have a small maternally inherited 16p11.2 deletion found which lies within a region of segmental duplications with location of representative genes (ATXN2L, SH2B1 and LAT) noted. Subject 4 (c) has a large 10.69 Mb deletion at Xq27.1-q28. The deleted X chromosome region detected by the array is shown above the X chromosome ideogram.

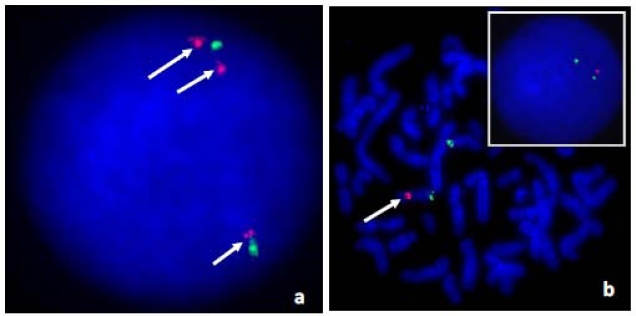

Fig. (3).

Confirmatory fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) studies in Subjects 1, 2, and 3. In Subject 1 (panel a), the 10q23.2 (RP11-830J13) Rhodamine labeled BAC clone showed 3 copies (arrows) while the “control” chr. 10p11.21 FITC labeled BAC clone (RP11-876K20) showed normal hybridization pattern in interphase nuclei. Subjects 2, 3 and their mother shared the same 16p11.2 deletion (panel b) detected by the RP11-1136I3 (Rhodamine) BAC clone (arrow). The RP11-133L7 (FITC) BAC clone was the control probe.

Subjects 2 and 3

At 8 months of age, this Hispanic boy (Fig. 1c,1d) was evaluated for a suspected diagnosis of Prader-Willi syndrome because of his rapid weight gain and developmental delay. He was born at term and his mother had gestational diabetes mellitus. He had feeding difficulties for the first four months of life followed by developmental delays. His weight was 11.53 kg (>95th centile), length was 73.5 cm (50-75th centile) and BMI was 21.3 kg/m2 with a head circumference of 46.25 cm (75-90th centile). Frontal bossing was noted with moderate micrognathia, almond-shaped eyes, flat-nasal bridge, small appearing hands with distal tapering of fingers, deep palmar creases, one large café au lait spot on the left shoulder, undescended testes, and a head lag. DNA methylation testing for the Prader-Willi syndrome/Angelman syndrome region at chromosome 15q11.2 was normal (not shown). Genomic DNA oligo-array CGH analysis was then performed which showed a small 16p11.2 deletion (base position: 28,730,299-29,009,896; hg18) (Fig. 2b) and confirmed by FISH analysis using the BAC clone “RP11-1136I3” (Fig. 3b).

His mother was 30 years old, weighed 58.2 kg and was 150.3 cm tall. Her BMI was 25.8 kg/m2. She reported no significant health problems. Her other child (subject 3), a 34 month old daughter with obesity and speech delay, presented for genetic evaluation. The pregnancy was complicated by preterm labor at 36 weeks gestation with a history of maternal syphilis and gestational diabetes mellitus. Birth weight was 2.43 kg (39th centile), length 45.9 cm (46th centile), BMI was 11.5 kg/m2 and head circumference was 29.5 cm (6th centile). Congenital syphilis was excluded. She walked at 12 months of age. At 34 months of age, her weight was 19.9 kg (>97th centile), length was 97.5 cm (>95th centile), BMI was 20.9 kg/m2 and head circumference was 50 cm (90th centile). She presented with frontal bossing, one small café au lait spot on the lower back and delayed speech (Fig. 1e). Her serum liver and lipid profiles, renal ultrasound and bone age were normal for her age. These family members also showed the same 16p11.2 deletion as subject 2.

Subject 4

At 8 years of age, this Caucasian girl was evaluated and found to have a de novo germline deletion involving chromosome Xq27.1-q28 region by standard chromosome analysis (not shown). This chromosome abnormality was confirmed by aCGH analysis and a 10.69 Mb deletion was found (base position: 139,354,859-150,046,723; hg18) (Fig. 2c). She was the product of a 37 weeks gestation complicated by maternal tobacco smoking. Delivery was spontaneous vaginal and birth weight was 2.41 kg. Postnatal health problems included a slow weight gain, hypotonia, microcephaly, global developmental delays, right eye esotropia, and chronic constipation. A brain CT scan, thyroid function, quantitative plasma amino acid and urine organic acid profiles were all normal. She also had normal MECP2 gene sequencing, SNRPN gene methylation testing for PWS and FMR1 gene methylation with the CGG repeat determination at 20 indicating one allele. Quantitative urine mucopolysaccharides levels were elevated at 20.8 (<12.0 mg/mmoL Cr). Her weight was 33.7 kg (90-95th centile), height was 100 cm (<5th centile), head circumference was 50 cm, and BMI 33.7 was kg/m2. She was dysmorphic (myopathic facies, dolicho-microcephaly, almond-shaped eyes, narrow, long face and nose, pinched nostrils, prominent philtrum, small mouth, small ear lobes, and a narrow palate). She had truncal obesity, small hands and feet and severe speech and cognitive delays (Fig. 1f,1g). She was treated with growth hormone.

Molecular Cytogenetic Studies

In this study, four individuals were studied and found to have various chromosome aberrations associated with early onset obesity and other findings. Standard chromosome analysis of peripheral blood lymphocytes was initially performed in subject 4. DNA was isolated according to standard procedures and used for chromosome microarray studies. FISH analysis used genomic region specific BAC clones (Table 1) for Subjects 1, 2 and 3 and obtained from The Center for Applied Genomics (TCAG, Toronto, Canada). Quantitative PCR amplification of an Xq27.1 gene was used in Subject 4 to confirm the cytogenetic deletion (not shown). Three separate Agilent Technologies (Santa Clara, CA) oligonucleotide CGH array platforms (105K platform in Subject 1, 180K platform in Subjects 2 and 3 and 244K platform in Subject 4) were used with genomic DNA isolated following manufacturer’s recommendations and as previously described [3,4]. Each sample was subjected to one hybridization experiment using Cy3 fluorescently labeled test DNA paired with Cy5 labeled reference DNA. Probe hybridization signals were expressed as the log2 ratio of signal intensities of a test sample versus signal intensities of a reference sample and array data were analyzed using the Nexus Copy Number™ software (Biodiscovery, El Segundo, CA) based on the genome content sourced from the UCSC hg18 human genome (NCBI build 36, March 2006). Array CGH studies for Subjects 1, 2 and 3 were performed at CombiMatrixTM (Irvine, CA) while Subject 4 was studied at The Children’s Mercy Hospital Microarray Laboratory (Kansas City, MO).

Table 1.

Summary of the Clinical and Molecular Findings in the Four Reported Subjects in our Study

| Subject | Chromosome abnormality | FISH study/ Probe | Clinical features |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Chr. 10q22.3-q23.2 dup (81,281,895-89,091,213bp) | Yes/ RP11-830J13 | 34 yr old, early onset obesity, idiopathic urticaria, endometriosis, atrophy & scarring of right kidney |

| 2 and 3 | Chr. 16p11.2 del (28,730,299-29,009,896 bp)mat | Yes/ RP11-1136I3 | Early onset obesity, developmental and speech delays |

| 4 | Chr. Xq27.1-q28 del (139,354,859-150,046,723 bp)dn | No | Early onset obesity (truncal), hypotonia, microcephaly, global developmental delays, right esotropia, short stature |

Literature Search Discovery

To further identify structural chromosome abnormalities playing a role in the causations of obesity, we preformed an online PubMed search for structural chromosome abnormalities reported in the literature using key words such obesity, chromosome deletion, duplication, translocation, inversion, and the names of leading genetics journals. The results of this search were compiled in Table 2.

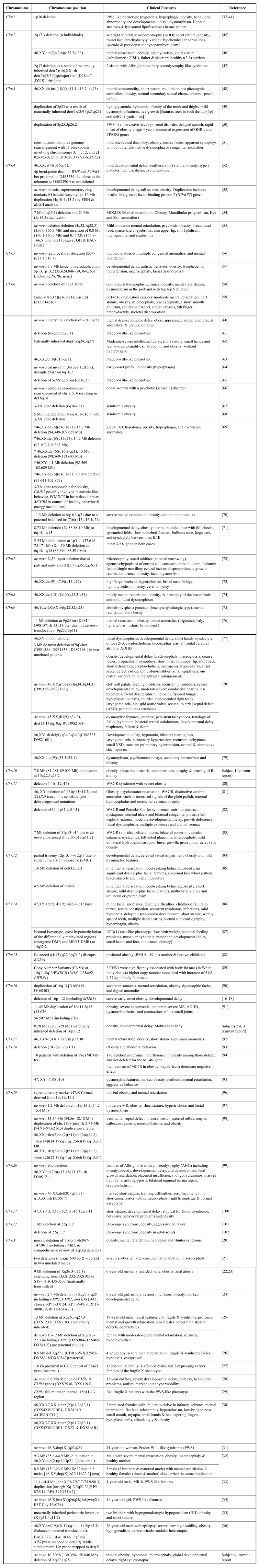

Table 2.

Summary of Reported Chromosomal Abnormalities in the Literature from Individuals with Syndromic Obesity excluding Prader-Willi Syndrome

RESULTS

The major clinical findings in our four individuals were summarized in Table 1 and the results of their molecular studies. While obesity is a shared clinical finding, each individual had a different complex phenotype due to their unrelated molecular genetic abnormality except for Subjects 2 and 3 who were siblings. The aCGH profiles for Subjects 1 through 4 are shown in Fig. (2a-2c) representing the regions of genomic abnormality. The regions recognized segmental duplications (Fig. 2a,2b) known to mediate the copy number abnormalities of the chromosomes involved are highlighted. In Fig. (3a,3b), the duplication of chromosome 10q22.3-q23.2 and deletion of 16p11.2 were confirmed by FISH analysis. The BAC clones used for the FISH studies in each subject are shown in Table 1. The parents of subject 4 had normal peripheral blood chromosomes studies.

DISCUSSION

In this group of four subjects, generalized or truncal obesity was a major clinical feature. Early feeding difficulties (Subjects 2 and 4), hypotonia (Subject 4) and developmental delays (Subjects 2 and 4) followed by rapid weight gain led to the clinical suspicion of Prader-Willi syndrome (PWS). The PWS diagnosis was largely excluded by the normal SNRPN gene methylation studies which ruled out genetic defects of the PWS/AS (Angelman syndrome) region. Subject 1 also presented as an adult with an unexplained complex phenotype which warranted a detailed genetic evaluation and revealed a chromosome 10q22.3-q23.2 duplication. Facial dysmorphism was noticeable in each of the four individuals but the most striking observations were seen in Subject 4. Developmental and speech delays were present in subjects 2, 3 and 4.

Human DNA fragments >1 kb in size and of >90% DNA sequence identity have been termed low copy repeats (LCRs) or segmental duplications which can stimulate or mediate constitutional (i.e., inherited; both recurrent and non-recurrent) and somatic genomic rearrangements [5]. The advent and application of aCGH resulted in the identification of an increasing number of genomic disorders (microdeletion/microduplication syndromes) with nonallelic homologous recombination (NAHR) as the predominant underlying molecular mechanism using the flanking LCRs as recombination substrates [5]. Examples of common copy repeat loci involved in genomic disorders due to copy number abnormalities include 7q11.2, 15q11.2, 22q11.2 and others. The phenotypic consequences observed in these disorders may result from mechanisms such as deletions or duplications of dosage sensitive genes, position effect, unmasking of recessive mutations or functional polymorphisms of the remaining allele when a deletion occurs, or through effects of transvection (interaction between alleles on homologous chromosomes) [6,7].

The 10q22.3-q23.2 region is characterized by a complex set of low-copy repeats (LCRs 3, 4), which can give rise to various genomic changes mediated by nonallelic homologous recombination. Large duplications involving the 10q22-q23 region are very rare with only four cases reported overlapping this region [8-12]. However, six microduplications within the 10q22.3-q23.3 region have been reported recently by van Bon et al. [13]. Subject 1 in this report has a large 7.8 Mb duplication at 10q22.3-q23.2 which is between LCR 3 and 4. It is interesting to note that the hsa-miRNA346 gene (human microRNA) lies within this duplicated region (base position: 88,022,451-88,026,545). Microdeletion/duplications involving mirRNA genes may add another level of complexity because of their multiple target genes. For example, miRNA346 has 72 predicted targets [miRBase, 2011]. Unlike the six individuals reported by van Bon et al. [13], Subject 1 has severe obesity and recurrent large lipomas requiring surgical resection. She is not known to have intestinal polyposis. The 10q22.3-q23.2 duplication region seen in this subject does not include the PTEN and BMPR1 genes which cause Bannayan-Riley-Ruvalcaba syndrome (BRRS) and Juvenile Polyposis Syndrome (JPS), respectively. Lipomatosis is a known feature of BRRS. In addition, positive linkage with D10S535 (10q22.3; base position:76,240,707-76,440,904, hg19), and D10S1267 (10q24.32; chr10:104,278,612-104,478,824bp) and obesity phenotypes have been reported separately in both White and African-American individuals [14,15]. We speculate that our subject’s 10q duplication may have disrupted the expression of a dosage sensitive gene such as PTEN or another gene or non-coding signal in this region contributing to her recurrent lipomatosis and obesity.

The clinical and molecular findings in Subjects 2 and 3 are consistent with the recently described 16p11.2 obesity- related microdeletion syndrome (position 28.7-28.9 Mb) [16-18]. We mapped this deletion to a region of segmental duplications at 16p11.2 and found it to be maternally inherited and confirmed by FISH analysis. This deletion encompasses the SH2B1 gene which is implicated in murine obesity [19]. The mother of these two affected children appeared to be non-penetrant for this pathogenic copy number variant, a phenomenon known to occur. This locus appears to be distinct from the more proximal 16p11.2 (29.5-30.1 Mb) autism associated locus.

Several subjects with contiguous gene deletions involving the FMR1 gene locus have been reported and were comprehensively reviewed recently by Coffee et al. [20]. They cited a total of 71 deletions that were classified as small or large deletions. Subject 4 who has severe developmental delays, facial dysmorphism and truncal obesity was found to carry a de novo 10.69 Mb deletion at Xq27.1-q28 (Fig. 2c). Major genes within the deleted region include FMR1, FMR2, IDS, MTM1 and MTMR1. In addition to Hunter syndrome and myotubular myopathy, other phenotypic abnormalities noted in other individuals with contiguous gene deletions including the FMR1 are obesity [21,22,24], cherubism [23], overgrowth [25,26], and macrocephaly [27,28]. A Prader-Willi syndrome-like phenotype with obesity has been described in fragile X syndrome individuals with the CGG expansion mutation [29], indicating that the obesity is probably due to loss of FMR1 function and interaction with other genes. In addition to these deletions, 4 duplications [30-33], 2 inversions [34,35] and 1 translocation [36] involving the X chromosome have been reported to be associated with obesity.

In Table 2, we summarized reports from the literature in which structural chromosome abnormalities were reported with syndromic obesity [20-102]. Those involving chromosome 15q11.2 and Prader-Willi syndrome were excluded as this genetic obesity syndrome will be described separately in this journal issue. The most frequently reported chromosome regions were 15q (not shown), 6q [58-71] and Xq [20-36]. Single-minded 1 (SIM1) gene (chr.6q16.3, position:100,836,750-100,911,551; hg19) mutations are one of the few known causes of nonsyndromic and PWS- like monogenic obesity in both humans and mice.

The mouse Sim1 gene is expressed in the developing kidney and central nervous system and essential for formation of the supraoptic and paraventricular (PVN) nuclei of the hypothalamus implicated in the regulation of body weight. The melanocortin-4 receptor (MC4R) gene is expressed in these brain regions and are physiologic targets of alpha-melanocyte-stimulating hormone which inhibits food intake [103]. Michaud et al. [104] also demonstrated that the lethal homozygous Sim1 (Sim1 -/-) null mutation in mice causes lack of the paraventricular nucleus. However, Sim1 heterozygotes were viable but developed early-onset hyperphagic obesity with clinical features of metabolic syndrome. A remarkable decrease in hypothalamic oxytocin (Oxt) and PVN melanocortin 4 receptor (Mc4r) mRNA was also demonstrated in conditional Sim1 homozygous and germ line Sim1 heterozygous mutant mice suggesting that hyperphagic obesity may be attributable to changes in the leptin-melanocortin-oxytocin pathway [105].

Other genes such as MC4R, leptin and leptin receptor, Ghrelin (GHRL), peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARG), oxytocin receptor (OXTR), prohormone convertase-1 and proopiomelanocortin have been implicated in human obesity and will be discussed elsewhere in this journal issue. Heterozygous or bi-allelic disruptions of these genes by structural chromosome abnormalities may potentially lead to obesity. For example, Bittel et al. [50] reported a boy with marked obesity and a duplication of chromosome 3p25.3-p26.2 region which contains GHRL and PPARG. They reported increased expression of these genes which appears to contribute to the obesity seen in this individual. In most of the remaining chromosomal abnormalities in individuals with obesity identified in our literature search listed in Table 2, no specific obesity- related gene was identified.

In conclusion, obesity is a highly complex multifactorial clinical phenotype with significant genetic predisposition. So far, several single genes and genomic loci scattered on most of the chromosomes except the Y chromosome have been reported and are involved in the pathogenesis of human obesity. The genetic basis of syndromic obesity in our four selected individuals was identified or confirmed using aCGH microarray analysis. Improved understanding of the specific mechanisms of these genetic predispositions will be crucial for the personalized management of individuals with various forms of obesity, particularly in early childhood.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank the subjects and their parents for participating and support in this study. We also wish to especially thank Dr. Shihui Yu for performing the aCGH study on subject 4 and the many clinicians who provided excellent medical care of these individuals.

WEB RESOURCES

The Center for Applied Genomics (TCAG): http://www.cag.icph.org/

Database of Chromosome Genomic Variants (http://projects.tcag.ca/variation)

miRBase: the microRNA database: http://www.mirbase.org/

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURE

Karine Hovanes, Ph.D. is a Director at CombiMatrix Diagnostics: E.L.Y. and M.J.D. have no conflict of interests to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bouchard C, Perusse L. Current status of the human obesity gene map. Obes. Res. 1996;4:81–90. doi: 10.1002/j.1550-8528.1996.tb00516.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rankinen T, Zuberi A, Chagnon YC, Weisnagel SJ, Argyropoulos G, Walts B, Pe´russe L, Bouchard C. The Human Obesity Gene Map: The 2005 Update. Obesity. 2006;14:529– 644. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yu S, Kielt M, Stegner AL, Kibiryeva N, Bittel DC, Cooley LD. Quantitative real- time PCR for the verification of genomic imbalances detected by microarray-based comparative genomic hybridization. Genet. Test Mol. Biomarkers. 2009;13:751–760. doi: 10.1089/gtmb.2009.0056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yu S, Bittel DC, Kibiryeva N, Zwick DL, Cooley LD. Validation of the Agilent 244K oligonucleotide array-based comparative genomic hybridization platform for clinical cytogenetic diagnosis. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 2009;132:349–360. doi: 10.1309/AJCP1BOUTWF6ERYS. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stankiewicz P, Lupski JR. Structural variation in the human genome and its role in disease. Annu. Rev. Med. 2010;61:437–455. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-100708-204735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kurotaki N, Shen JJ, Touyama M, Kondoh T, Visser R, Ozaki T, Nishimoto J, Shiihara T, Uetake K, Makita Y, Harada N, Raskin S, Brown CW, Höglund P, Okamoto N, Lupski JR. Phenotypic consequences of genetic variation at hemizygous alleles: Sotos syndrome is a contiguous gene syndrome incorporating coagulation factor twelve (FXII) deficiency. Genet. Med. 2005;7:479–483. doi: 10.1097/01.gim.0000177419.43309.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lupski JR, Stankiewicz P. Genomic disorder mechanisms elucidated by breakpoint analysis of 17p rearrangements. PLoS Genet. 2005;1:e49. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0010049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goss PW, Voullaire L, Gardner RJ. Duplication 10q22-q25.1 due to intrachromosomal insertion: A second case. Ann. Genet. 1998;41:161–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Han JY, Kim KH, Jun HJ, Je GH, Glotzbach CD, Shaffer LG. Partial trisomy of chromosome 10(q22-q24) due to maternal insertional translocation (15;10) Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2004;131:190–193. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.30307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dufke A, Singer S, Borell-Kost S, Stotter M, Pflumm DA, Mau-Holzmann UA, Starke H, Mrasek K, Enders H. De novo structural chromosomal imbalances: Molecular cytogenetic characterization of partial trisomies. Cytogenet. Genome Res. 2006;114:342–350. doi: 10.1159/000094224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Erdogan F, Belloso JM, Gabau E, Ajbro KD, Guitart M, Ropers HH, Tommerup N, Ullmann R, Tümer Z, Larsen LA. Fine mapping of a de novo interstitial 10q22-q23 duplication in a patient with congenital heart disease and microcephaly. Eur. J. Med. Genet. 2008;51:81–86. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2007.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alliman S, Coppinger J, Marcadier J, Thiese H, Brock P, Shafer S, Weaver C, Asamoah A, Leppig K, Dyack S, Morash B, Schultz R, Torchia BS, Lamb AN, Bejjani BA. Clinical and molecular characterization of individuals with recurrent genomic disorder at 10q22. q23.2. Clin. Genet. 2010;78:162–168. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2010.01373.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van Bon BWM, Balciuniene J, Fruhman G, Sreenath Nagamani SC, Broome DL, Cameron E, Martinet D, Roulet E, Jacquemont S, Beckmann JS, Irons M, Potocki L, Lee B, Cheung SW, Patel A, Bellini M, Selicorni A, Ciccone R, Silengo M, Vetro A, Knoers NV, de Leeuw N, Pfundt R, Wolf B, Jira P, Aradhya S, Stankiewicz P, Brunner HG, Zuffardi O, Selleck SB, Lupski JR, and de Vries BBA. The phenotype of recurrent 10q22q23 deletions and duplications. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2011;19:400–408. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2010.211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dong C, Wang S, Li W, Li D, Zhao H, Price R. Interacting genetic loci on chromosomes 20 and 10 influence extreme human obesity. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2003;72:115–124. doi: 10.1086/345648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bell C, Benzinou M, Siddiq A, Lecoeur C, Dina C, Lemainque A, Clément K, Basdevant A, Guy-Grand B, Mein CA, Meyre D, Froguel P. Genome-wide linkage analysis for severe obesity in French Caucasians finds significant susceptibility locus on chromosome 19q. Diabetes. 2004;53:1857– 1865. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.7.1857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Walters RG, Jacquemont S, Valsesia A, de Smith AJ, Martinet D, Andersson J, Falchi M, Chen F, Andrieux J, Lobbens S, Delobel B, Stutzmann F, El-Sayed Moustafa JS, Chèvre JC, Lecoeur C, Vatin V, Bouquillon S, Buxton JL, Boute O, Holder-Espinasse M, Cuisset JM, Lemaitre MP, Ambresin AE, Brioschi A, Gaillard M, Giusti V, Fellmann F, Ferrarini A, Hadjikhani N, Campion D, Guilmatre A, Goldenberg A, Calmels N, Mandel JL, Le Caignec C, David A, Isidor B, Cordier MP, Dupuis-Girod S, Labalme A, Sanlaville D, Béri-Dexheimer M, Jonveaux P, Leheup B, Ounap K, Bochukova EG, Henning E, Keogh J, Ellis RJ, Macdermot KD, van Haelst MM, Vincent-Delorme C, Plessis G, Touraine R, Philippe A, Malan V, Mathieu-Dramard M, Chiesa J, Blaumeiser B, Kooy RF, Caiazzo R, Pigeyre M, Balkau B, Sladek R, Bergmann S, Mooser V, Waterworth D, Reymond A, Vollenweider P, Waeber G, Kurg A, Palta P, Esko T, Metspalu A, Nelis M, Elliott P, Hartikainen AL, McCarthy MI, Peltonen L, Carlsson L, Jacobson P, Sjöström L, Huang N, Hurles ME, O'Rahilly S, Farooqi IS, Männik K, Jarvelin MR, Pattou F, Meyre D, Walley AJ, Coin LJ, Blakemore AI, Froguel P, Beckmann JS. A new highly penetrant form of obesity due to deletions on chromosome 16p11. Nature. 2010;463:671–675. doi: 10.1038/nature08727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bochukova EG, Huang N, Keogh J, Henning E, Purmann C, Blaszczyk K, Saeed S, Hamilton- Shield J, Clayton-Smith J, O'Rahilly S, Hurles ME, Farooqi IS. Large, rare chromosomal deletions associated with severe early-onset obesity. Nature. 2010;463:666–670. doi: 10.1038/nature08689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bachmann-Gagescu R, Mefford HC, Cowan C, Glew GM, Hing AV, Wallace S, Bader PI, Hamati A, Reitnauer PJ, Smith R, Stockton DW, Muhle H, Helbig I, Eichler EE, Ballif BC, Rosenfeld J, Tsuchiya KD. Recurrent 200-kb deletions of 16p11.2 that include the SH2B1 gene are associated with developmental delay and obesity. Genet. Med. 2010;12:641–647. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181ef4286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ren D, Zhou Y, Morris D, Li M, Li Z, Rui L. Neuronal SH2B1 is essential for controlling energy and glucose homeostasis. J. Clin. Invest. 2007;117:397–406. doi: 10.1172/JCI29417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Coffee B, Ikeda M, Budimirovic DB, Hjelm LN, Kaufmann WE, Warren ST. Research review mosaic FMR1 deletion causes fragile x syndrome and can lead to molecular misdiagnosis: A case report and review of the literature. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part A. 2008;146A:1358–1367. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hirst M, Grewal P, Flannery A, Slatter R, Maher E, Barton D, Fryns JP, Davies K. Two new cases of FMR1 deletion associated with mental impairment. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1995;56:67–74. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Quan F, Zonana J, Gunter K, Peterson KL, Magenis RE, Popovich BW. An atypical case of fragile X syndrome caused by a deletion that includes the FMR1 gene. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1995;56:1042–1051. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Quan F, Grompe M, Jakobs P, Popovich BW. Spontaneous deletion in the FMR1 gene in a patient with fragile X syndrome and cherubism. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1995;4:1681–1684. doi: 10.1093/hmg/4.9.1681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Probst FJ, Roeder ER, Enciso VB, Ou Z, Cooper ML, Eng P, Li J, Gu Y, Stratton RF, Chinault AC, Shaw CA, Sutton VR, Cheung SW, Nelson DL. Chromosomal microarray analysis (CMA) detects a large X chromosome deletion including FMR1, FMR2, and IDS in a female patient with mental retardation. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2007;143A:1358–1365. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wolff DJ, Gustashaw KM, Zurcher V, Ko L, White W, Weiss L, Van Dyke DL, Schwartz S, Willard HF. Deletions in Xq26.3-q27.3 including FMR1 result in a severe phenotype in a male and variable phenotypes in females depending upon the X inactivation pattern. Hum. Genet. 1997;100:256–261. doi: 10.1007/s004390050501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parvari R, Mumm S, Galil A, Manor E, Bar-David Y, Carmi R. Deletion of 8.5 Mb, including the FMR1 gene, in a male with the fragile X syndrome phenotype and overgrowth. Am. J. Med. Genet. 1999;83:302–307. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-8628(19990402)83:4<302::aid-ajmg13>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meijer H, de Graaff E, Merckx DM, Jongbloed RJ, de Die-Smulders CE, Engelen JJ, Fryns JP, Curfs PM, Oostra BA. A deletion of 1.6 kb proximal to the CGG repeat of the FMR1 gene causes the clinical phenotype of the fragile X syndrome. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1994;3:615–620. doi: 10.1093/hmg/3.4.615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moore SJ, Strain L, Cole GF, Miedzybrodzka Z, Kelly KF, Dean JC. Fragile X syndrome with FMR1 and FMR2 deletion. J. Med. Genet. 1999;36:565–566. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.de Vries BB, Fryns JP, Butler MG, Canzian F, Wesby-van Swaay E, van Hemel JO, Oostra BA, Halley DJ, Niermeijer MF. Clinical and molecular studies in fragile X patients with a Prader- Willi-like phenotype. J. Med. Genet. 1993;30:761–766. doi: 10.1136/jmg.30.9.761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tümer Z, Wolff D, Silahtaroglu AN, Orum A, Brøndum-Nielsen K. Characterization of a supernumerary small marker X chromosome in two females with similar phenotypes. Am. J. Med. Genet. 1998;76:45–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Monaghan KG, Van Dyke DL, Feldman GL. Prader-Willi-like syndrome in a patient with an Xq23q25 duplication. Am. J. Med. Genet. 1998;80:227–231. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-8628(19981116)80:3<227::aid-ajmg10>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tzschach A, Chen W, Erdogan F, Hoeller A, Ropers HH, Castellan C, Ullmann R, Schinzel A. Characterization of interstitial Xp duplications in two families by tiling path array CGH. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2008;146A:197–203. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gabbett MT, Peters GB, Carmichael JM, Darmanian AP, Collins FA. Prader-Willi syndrome phenocopy due to duplication of Xq21.1-q21.31, with array CGH of the critical region. Clin. Genet. 2008;73:353–359. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2007.00960.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Florez L, Anderson M, Lacassie Y. De novo paracentric inversion (X)(q26q28) with features mimicking Prader-Willi syndrome. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2003;121A:60–64. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.20129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Talaban R, Sellick GS, Spendlove HE, Howell R, King C, Reckless J, Newbury-Ecob R, Houlston RS. Inherited pericentric inversion (X)(p11.4q11.2) associated with delayed puberty and obesity in two brothers. Genome Res. 2005;109:480–484. doi: 10.1159/000084206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Balci S, Unal A, Engiz O, Aktas D, Liehr T, Gross M, Mrasek K, Saygi S. Bilateral periventricular nodular heterotopia, severe learning disability, and epilepsy in a male patient with 46,XY,der(19)t(X;19)(q11.1-11.2;p13.3) Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2007;49:219–224. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2007.00219.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Eugster EA, Berry SA, Hirsch B. Mosaicism for deletion 1p36.33 in a patient with obesity and hyperphagia. Am. J. Med. Genet. 1997;70:409–412. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-8628(19970627)70:4<409::aid-ajmg14>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Slavotinek A, Shaffer LG, Shapira SK. Monosomy 1p36. J. Med. Genet. 1999;36:657–663. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Finelli P, Giardino D, Russo S, Gottardi G, Cogliati F, Grugni G, Natacci F, Larizza L. Refined FISH characterization of a de novo 1p22-p36.2 paracentric inversion and associated 1p21-22 deletion in a patient with signs of 1p36 microdeletion syndrome. Am. J. Med. Genet. 2001;99:308–313. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Neumann LM, Polster T, Spantzel T, Bartsch O. Unexpected death of a 12 year old boy with monosomy 1p36. Genet. Couns. 2004;15:19–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.D'Angelo CS, Da Paz JA, Kim CA, Bertola DR, Castro CI, Varela MC, Koiffmann CP. Prader-Willi-like phenotype: investigation of 1p36 deletion in 41 patients with delayed psychomotor development, hypotonia, obesity and/or hyperphagia, learning disabilities and behavioral problems. Eur. J. Med. Genet. 2006;49:451–460. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2006.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Haimi M, Iancu TC, Shaffer LG, Lerner A. Severe lysosomal storage disease of liver in del(1)(p36): A new presentation. Eur. J. Med. Genet. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2010.11.012. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.D'Angelo CS, Kohl I, Varela MC, de Castro CI, Kim CA, Bertola DR, Lourenço CM, Koiffmann CP. Extending the phenotype of monosomy 1p36 syndrome and mapping of a critical region for obesity and hyperphagia. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2010;152A:102–110. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.33160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tsuyusaki Y, Yoshihashi H, Furuya N, Adachi M, Osaka H, Yamamoto K, Kurosawa K. 1p36 deletion syndrome associated with Prader-Willi-like phenotype. Pediatr. Int. 2010;52:547–550. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-200X.2010.03090.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Phelan MC, Rogers RC, Clarkson KB, Bowyer FP, Levine MA, Estabrooks LL, Severson MC, Dobyns WB. Albright hereditary osteodystrophy and del(2) (q37.3) in four unrelated individuals. Am. J. Med. Genet. 1995;58:1–7. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320580102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Giardino D, Finelli P, Gottardi G, De Canal G, Della Monica M, Lonardo F, Scarano G, Larizza L. Narrowing the candidate region of Albright hereditary osteodystrophy-like syndrome by deletion mapping in a patient with an unbalanced cryptic translocation t(2;6)(q37.3;q26) Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2003;122A:261–265. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.20287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fernández-Rebollo E, Pérez O, Martinez-Bouzas C, Cotarelo-Pérez MC, Garin I, Ruibal JL, Pérez-Nanclares G, Castaño L, de Nanclares GP. Two cases of deletion 2q37 associated with segregation of an unbalanced translocation 2;21: Choanal atresia leading to misdiagnosis of CHARGE syndrome. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2009;160:711–717. doi: 10.1530/EJE-08-0865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Al-Attia HM, Sedaghatian MR. Mental retardation/shortness of stature/multiple minor anomalies syndrome associated with insertion of 3q material into 18p. Am. J. Med. Genet. 1995;56:35–38. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320560110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McClure RJ, Telford N, Newell SJ. A mild phenotype associated with der(9)t(3;9) (p25;p23) J. Med. Genet. 1996;33:625–627. doi: 10.1136/jmg.33.7.625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bittel DC, Kibiryeva N, Dasouki M, Knoll JH, Butler MG. A 9-year-old male with a duplication of chromosome 3p25.3p26.2: clinical report and gene expression analysis. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2006;140:573–579. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Borg K, Stankiewicz P, Bocian E, Kruczek A, Obersztyn E, Lupski JR, Mazurczak T. Molecular analysis of a constitutional complex genome rearrangement with 11 breakpoints involving chromosomes 3, 11, 12, and 21 and a approximately 0.5-Mb submicroscopic deletion in a patient with mild mental retardation. Hum. Genet. 2005;118:267–275. doi: 10.1007/s00439-005-0021-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Blackett PR, Li S, Mulvihill JJ. Ring chromosome 4 in a patient with early onset type 2 diabetes, deafness, and developmental delay. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2005;137:213–216. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.20386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bonnet C, Zix C, Grégoire MJ, Brochet K, Duc M, Rousselet F, Philippe C, Jonveaux P. Characterization of mosaic supernumerary ring chromosomes by array-CGH: segmental aneusomy for proximal 4q in a child with tall stature and obesity. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2006;140:233–237. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.van Haelst MM, Wang R, Kantaputra PN, Palmer R, Beales P. Obesity syndrome, MOMES caused by deletion-duplication (4q35.1del and 5p14.3 dup) Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2009;149A:833–834. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tzschach A, Menzel C, Erdogan F, Istifli ES, Rieger M, Ovens-Raeder A, Macke A, Ropers HH, Ullmann R, Kalscheuer V. Characterization of an interstitial 4q32 deletion in a patient with mental retardation and a complex chromosome rearrangement. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2010;152A:1008–1012. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.33343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fryns JP, Kleczkowska A, Smeets E, Thiry P, Geutjens J, Van den Berghe H. Cohen syndrome and de novo reciprocal translocation t(5;7)(q33 ;p15.1). Am. J. Med. Genet. 1990;37(4):546–547. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320370425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Oexle K, Hempel M, Jauch A, Meitinger T, Rivera-Brugués N, Stengel-Rutkowski S, Strom T. 3.7 Mb tandem microduplication in chromosome 5p13.1-p13.2 associated with developmental delay, macrocephaly, obesity, and lymphedema. Further characterization of the dup(5p13) syndrome. Eur. J. Med. Genet. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2010.12.012. [epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fryns JP, Bettens W, Van den Berghe H. Distal deletion of the long arm of chromosome 6: A specific phenotype? Am. J. Med. Genet. 1986;1:175–178. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320240122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Roland B, Lowry RB, Cox DM, Ferreira P, Lin CC. Familial complex chromosomal rearrangement resulting in duplication/deletion of 6q14 to 6q16. Clin. Genet. 1993;43(3):117–121. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.1993.tb04434.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Villa A, Urioste M, Bofarull JM, Martínez-Frías ML. De novo interstitial deletion q16.2q21 on chromosome 6. Am. J. Med. Genet. 1995;55:379–383. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320550326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Stein CK, Stred SE, Thomson LL, Smith FC, Hoo JJ. Interstitial 6q deletion and Prader-Willi-like phenotype. Clin. Genet. 1996;49:306–310. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.1996.tb03794.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Smith A, Jauch A, Slater H, Robson L, Sandanam T. Syndromal obesity due to paternal duplication 6(q24.3-q27) Am. J. Med. Genet. 1999;84:125–131. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-8628(19990521)84:2<125::aid-ajmg8>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gilhuis HJ, van Ravenswaaij CM, Hamel BJ, Gabreëls FJ. Interstitial 6q deletion with a Prader-Willi-like phenotype: A new case and review of the literature. Eur. J. Paediatr. Neurol. 2000;4:39–43. doi: 10.1053/ejpn.1999.0259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Holder JL Jr, Butte NF, Zinn AR. Profound obesity associated with a balanced translocation that disrupts the SIM1 gene. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2000;9:101–108. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.1.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Faivre L, Cormier-Daire V, Lapierre JM, Colleaux L, Jacquemont S, Geneviéve D, Saunier P, Munnich A, Turleau C, Romana S, Prieur M, De Blois MC, Vekemans M. Deletion of the SIM1 gene (6q16.2) in a patient with a Prader-Willi-like phenotype. J. Med. Genet. 2002;39:594–596. doi: 10.1136/jmg.39.8.594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lespinasse J, Bugge M, Réthoré MO, North MO, Lundsteen C, Kirchhoff M. De novo complex chromosomal rearrangements (CCR) involving chromosome 1, 5, and 6 resulting in microdeletion for 6q14 in a female carrier with psychotic disorder. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2004;128A:199–203. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.30064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Varela MC, Simões-Sato AY, Kim CA, Bertola DR, De Castro CI, Koiffmann CP. A new case of interstitial 6q16.2 deletion in a patient with Prader-Willi-like phenotype and investigation of SIM1 gene deletion in 87 patients with syndromic obesity. Eur. J. Med. Genet. 2006;49:298–305. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2005.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wang JC, Turner L, Lomax B, Eydoux P. A 5-Mb microdeletion at 6q16.1-q16.3 with SIM gene deletion and obesity. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2008;146A:2975–2978. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bonaglia MC, Ciccone R, Gimelli G, Gimelli S, Marelli S, Verheij J, Giorda R, Grasso R, Borgatti R, Pagone F, Rodrìguez L, Martinez-Frias ML, van Ravenswaaij C, Zuffardi O. Detailed phenotype-genotype study in five patients with chromosome 6q16 deletion: Narrowing the critical region for Prader-Willi-like phenotype. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2008;16:1443–1449. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2008.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Spreiz A, Müller D, Zotter S, Albrecht U, Baumann M, Fauth C, Erdel M, Zschocke J, Utermann G, Kotzot D. Phenotypic variability of a deletion and duplication 6q16.1 → q21 due to a paternal balanced ins(7;6)(p15;q16.1q21) Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2010;152A:2762–2767. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.33699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wentzel C, Lynch SA, Stattin EL, Sharkey FH, Annerén G, Thuresson AC. Interstitial deletions at 6q14.1-q15 associated with obesity, developmental delay and a distinct clinical phenotype. Mol. Syndromol. 2010;1:75–81. doi: 10.1159/000314025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Frints SG, Schrander-Stumpel CT, Schoenmakers EF, Engelen JJ, Reekers AB, Van den Neucker AM, Smeets E, Devlieger H, Fryns JP. Strong variable clinical presentation in 3 patients with 7q terminal deletion. Genet. Couns. 1998;9:5–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kozma C, Haddad BR, Meck JM. Trisomy 7p resulting from 7p15;9p24 translocation: Report of a new case and review of associated medical complications. Am. J. Med. Genet. 2000;91:286–290. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-8628(20000410)91:4<286::aid-ajmg9>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kleefstra T, van de Zande G, Merkx G, Mieloo H, Hoovers JM, Smeets D. Identification of an unbalanced cryptic translocation between the chromosomes 8 and 13 in two sisters with mild mental retardation accompanied by mild dysmorphic features. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2000;8:637–640. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Menten B, Buysse K, Vandesompele J, De Smet E, De Paepe A, Speleman F, Mortier G. Identification of an unbalanced X-autosome translocation by array CGH in a boy with a syndromic form of chondrodysplasia punctata brachytelephalangic type. Eur. J. Med. Genet. 2005;48:301–309. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2005.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Serra A, Bova R, Bellanova G, Chindemi A, Zappata S, Brahe C. Partial 9p monosomy in a girl with a tdic(9p23;13p11) translocation, minor anomalies, obesity, and mental retardation. Am. J. Med. Genet. 1997;71:139–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Cormier-Daire V, Molinari F, Rio M, Raoul O, de Blois MC, Romana S, Vekemans M, Munnich A, Colleaux L. Cryptic terminal deletion of chromosome 9q34: a novel cause of syndromic obesity in childhood? J. Med. Genet. 2003;40:300–303. doi: 10.1136/jmg.40.4.300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Neas KR, Smith JM, Chia N, Huseyin S, St Heaps L, Peters G, Sholler G, Tzioumi D, Sillence DO, Mowat D. Three patients with terminal deletions within the subtelomeric region of chromosome 9q. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2005;132:425–430. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.30496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Gawlik-Kuklinska K, Iliszko M, Wozniak A, Debiec-Rychter M, Kardas I, Wierzba J, Limon J. A girl with duplication 9q34 syndrome. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2007;143A:2019–2023. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Gül D, Ogur G, Tunca Y, Ozcan O. Third case of WAGR syndrome with severe obesity and constitutional deletion of chromosome (11)(p12p14) Am. J. Med. Genet. 2002;107:70–71. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.10013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Jung R, Rauch A, Salomons GS, Verhoeven NM, Jakobs C, Michael Gibson K, Lachmann E, Sass JO, Trautmann U, Zweier C, Staatz G, Knerr I. Clinical, cytogenetic and molecular characterization of a patient with combined succinic semialdehyde dehydrogenase deficiency and incomplete WAGR syndrome with obesity. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2006;88:256–260. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2006.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Brémond-Gignac D, Crolla JA, Copin H, Guichet A, Bonneau D, Taine L, Lacombe D, Baumann C, Benzacken B, Verloes A. Combination of WAGR and Potocki-Shaffer contiguous deletion syndromes in a patient with an 11p11.2-p14 deletion. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2005;13:409–413. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lennon PA, Scott DA, Lonsdorf D, Wargowski DS, Kirkpatrick S, Patel A, Cheung SW. WAGR(O?) syndrome and congenital ptosis caused by an unbalanced t(11;15)(p13;p11.2)dn demonstrating a 7 megabase deletion by FISH. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2006;140:1214–1218. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ausems MG, Schuil J, Van Raveswaaij-Arts C, De Pater JM. Clinical and molecular cytogenetic studies in a case with partial trisomy 12p due to a de novo supernumerary ring chromosome. Genet. Couns. 2004;15:405–410. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Niyazov DM, Nawaz Z, Justice AN, Toriello HV, Martin CL, Adam MP. Genotype/phenotype correlations in two patients with 12q subtelomere deletions. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2007;143A:2700–2705. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Lemire EG, Cardwell S. Unusual phenotype in partial trisomy 14. Am. J. Med. Genet. 1999;87:294–296. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-8628(19991203)87:4<294::aid-ajmg2>3.0.co;2-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Zechner U, Kohlschmidt N, Rittner G, Damatova N, Beyer V, Haaf T, Bartsch O. Epimutation at human chromosome 14q32.2 in a boy with a upd(14)mat-like clinical phenotype. Clin. Genet. 2009;75:251–258. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2008.01116.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Klar J, Asling B, Carlsson B, Ulvsbäck M, Dellsén A, Ström C, Rhedin M, Forslund A, Annerén G, Ludvigsson JF, Dahl N. RAR-related orphan receptor A isoform 1 (RORa1) is disrupted by a balanced translocation t(4;15)(q22.3) associated with severe obesity. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2005;13:928–934. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Chen Y, Liu YJ, Pei YF, Yang TL, Deng FY, Liu XG, Li DY, Deng HW. Copy number variations at the Prader-Willi syndrome region on chromosome 15 and associations with obesity in Whites. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2011 doi: 10.1038/oby.2010.323. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Stratakis CA, Lafferty A, Taymans SE, Gafni RI, Meck JM, Blancato J. Anisomastia associated with interstitial duplication of chromosome 16, mentalretardation, obesity, dysmorphic facies, and digital anomalies: Molecular mapping of a new syndrome by fluorescent in situ hybridization and microsatellites to16q13 (D16S419-D16S503) J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2000;85:3396–3401. doi: 10.1210/jcem.85.9.6776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.van den Berg L, de Waal HD, Han JC, Ylstra B, Eijk P, Nesterova M, Heutink P, Stratakis CA. Investigation of a patient with a partial trisomy 16q including the fat mass and obesity associated gene (FTO): fine mapping and FTO gene expression study. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2010;152A:630–637. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.33229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Rosenberg C, Borovik CL, Canonaco RS, Sichero LC, Queiroz AP, Vianna-Morgante AM. Identification of a supernumerary marker derived from chromosome 17 using FISH. Am. J. Med. Genet. 1995;59:33–35. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320590107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Wilson GN, Al Saadi AA. Obesity and abnormal behaviour associated with interstitial deletion of chromosome 18 (q12.2q21.1) J. Med. Genet. 1989;26:62–63. doi: 10.1136/jmg.26.1.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Cody JD, Reveles XT, Hale DE, Lehman D, Coon H, Leach RJ. Haplosufficiency of the melancortin-4 receptor gene in individuals with deletions of 18q. Hum. Genet. 1999;105:424–427. doi: 10.1007/s004390051125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Swingle HM, Ringdahl J, Mraz R, Patil S, Keppler-Noreuil K. Behavioral management of a long-term survivor with tetrasomy 18p. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2006;140:276–280. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Zung A, Rienstein S, Rosensaft J, Aviram-Goldring A, Zadik Z. Proximal 19q trisomy: A new syndrome of morbid obesity and mental retardation. Horm. Res. 2007;67:105–110. doi: 10.1159/000096419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Van der Aa N, Vandeweyer G, Kooy RF. A boy with mental retardation, obesity and hypertrichosis caused by a microdeletion of 19p13. 2. Eur. J. Med. Genet. 2010;53:291–293. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2010.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Davidsson J, Jahnke K, Forsgren M, Collin A, Soller M. Dup(19)(q12q13.2): Array-based genotype-phenotype correlation of a new possibly obesity-related syndrome. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2010;18:580–587. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Aldred MA, Aftimos S, Hall C, Waters KS, Thakker RV, Trembath RC, Brueton L. Constitutional deletion of chromosome 20q in two patients affected with albright hereditary osteodystrophy. Am. J. Med. Genet. 2002;113:167–172. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.10751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Braddock SR, Henley KM, Potter KL, Nguyen HG, Huang TH. Tertiary trisomy due to a reciprocal translocation of chromosomes 5 and 21 in a four-generation family. Am. J. Med. Genet. 2000;92:311–317. doi: 10.1002/1096-8628(20000619)92:5<311::aid-ajmg4>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.D'Angelo CS, Jehee FS, Koiffmann CP. An inherited atypical 1 Mb 22q11.2 deletion within the DGS/VCFS 3 Mb region in a child with obesity and aggressive behavior. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2007;143A:1928–1932. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Digilio MC, Marino B, Cappa M, Cambiaso P, Giannotti A, Dallapiccola B. Auxological evaluation in patients with DiGeorge/velocardiofacial syndrome (deletion 22q11.2 syndrome) Genet. Med. 2001;3:30–33. doi: 10.1097/00125817-200101000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Michaud JL, Rosenquist T, May NR, Fan CM. Development of neuroendocrine lineages requires the bHLH-PAS transcription factor SIM1. Genes & Dev. 1998;12:3264–3275. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.20.3264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Michaud J L, Boucher F, Melnyk A, Gauthier F, Goshu E, Levy E, Mitchell G A, Himms-Hagen J, Fan CM. Sim1 haploinsufficiency causes hyperphagia, obesity and reduction of the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2001;10:1465–1473. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.14.1465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Tolson KP, Gemelli T, Gautron L, Elmquist JK, Zinn AR, Kublaoui BM. Postnatal Sim1 deficiency causes hyperphagic obesity and reduced Mc4r and oxytocin expression. J. Neurosci. 2010;30:3803–3812. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5444-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]