Abstract

SoxAX cytochromes catalyze the formation of heterodisulfide bonds between inorganic sulfur compounds and a carrier protein, SoxYZ. They contain unusual His/Cys-ligated heme groups with complex spectroscopic signatures. The heme-ligating cysteine has been implicated in SoxAX catalysis, but neither the SoxAX spectroscopic properties nor its catalysis are fully understood at present. We have solved the first crystal structure for a group 2 SoxAX protein (SnSoxAX), where an N-terminal extension of SoxX forms a novel structure that supports dimer formation. Crystal structures of SoxAX with a heme ligand substitution (C236M) uncovered an inherent flexibility of this SoxA heme site, with both bonding distances and relative ligand orientation differing between asymmetric units and the new residue, Met236, representing an unusual rotamer of methionine. The flexibility of the SnSoxAXC236M SoxA heme environment is probably the cause of the four distinct, new EPR signals, including a high spin ferric heme form, that were observed for the enzyme. Despite the removal of the catalytically active cysteine heme ligand and drastic changes in the redox potential of the SoxA heme (WT, −479 mV; C236M, +85 mV), the substituted enzyme was catalytically active in glutathione-based assays although with reduced turnover numbers (WT, 3.7 s−1; C236M, 2.0 s−1). SnSoxAXC236M was also active in assays using SoxYZ and thiosulfate as the sulfur substrate, suggesting that Cys236 aids catalysis but is not crucial for it. The SoxYZ-based SoxAX assay is the first assay for an isolated component of the Sox multienzyme system.

Keywords: Bacteria, Circular Dichroism (CD), Cytochrome c, Electron Paramagnetic Resonance (EPR), Energy Metabolism, Enzymes, Protein Structure, Bacterial Sulfur Metabolism

Introduction

Oxidation of reduced sulfur compounds by bacteria is a key reaction of the biological sulfur cycle that results in the transformation of sometimes toxic and malodorous reduced sulfur compounds into non-toxic, bioavailable forms, such as sulfate (1–3). SoxAX cytochromes are heme-containing enzymes that play key roles in the initiation of thiosulfate oxidation in two major microbial sulfur oxidation pathways, the Sox pathway (2) and the Dsr/Sox pathway, that occur in chemolithotrophic and phototrophic sulfur-oxidizing bacteria, respectively (4).

SoxAX cytochromes are members of the rare heme-thiolate proteins (5) and can be classified into two groups of heterodimeric and one group of heterotrimeric proteins (6, 7), all of which contain the two heme-bearing subunits, SoxA and SoxX (7). In addition, the heterotrimeric SoxAX cytochromes contain another subunit, SoxK, that stabilizes the SoxAX complex (6). Heterodimeric forms of SoxAX (group 1 and 2) have been isolated from chemolithotrophic sulfur oxidizers, while the SoxAX cytochromes from phototrophic sulfur-oxidizing bacteria, such as Allochromatium vinosum, appear to be trimeric proteins (group 3) (6).

The two groups of heterodimeric SoxAX cytochromes can be distinguished based on the number of heme groups present in the SoxA subunit; while group 1 proteins have two heme groups/SoxA subunit (8, 9), in group 2 enzymes, only the heme group located close to the proposed SoxAX active site is present (7). The single heme SoxX subunits of group2 SoxAX proteins have a molecular mass of ∼22–26 kDa (group 1 and 3; ∼15–16 kDa) (6, 7), and the amino acid sequence similarity between these types of SoxX subunits is only 30–35%. To date, no crystal structures for the group 2 and group 3 SoxAX proteins have been reported despite the obvious differences in protein structure and the potential mechanistic implications.

Axial heme-thiolate ligation of a c-type heme group is unusual, and it has been noted that the His/Cys ligation of the SoxA hemes (6–8, 10) gives rise to a number of unusual features, including an extremely low redox potential below −400 mV (11, 12) and a modification of the ligand to a cysteine persulfide that was shown to exist in the group 1 SoxAX proteins (8, 9, 13). It has been suggested that this modification is responsible for the multiple EPR active states observed for the SoxA active site heme (7, 12–14).

In addition to their emerging structural diversity, the catalytic function of SoxAX cytochromes is only poorly understood at present. SoxAX enzymes are thought to initiate the degradation of thiosulfate by catalyzing the formation of a sulfur-sulfur bond between the sulfane sulfur of thiosulfate and a cysteine residue present on the SoxYZ carrier protein (Reaction 1) (2, 8, 12).

|

A sulfur transferase-like mechanism has been proposed for SoxAX, where thiosulfate becomes bound to the heme-ligating cysteine before being transferred to SoxYZ (8). However, this mechanism does not explain how two electrons liberated by the formation of a disulfide bond can be even temporarily stored in the SoxAX protein, given that the SoxA heme is unlikely to accept electrons under physiological conditions due to its low redox potential and there is no evidence of radical formation. Recently, the group 2 SoxAX protein from Starkeya novella (SnSoxAX)5 has been shown to bind 1 eq of copper/enzyme molecule (12), and line broadening observed for the SoxA EPR signature suggests that the copper is located close to the SoxA heme in the active site (12). Copper-loaded SoxAX showed enhanced activity in an in vitro assay that uses glutathione as the sulfur substrate and cytochrome c as an electron acceptor, leading to the formation of oxidized glutathione (12). The presence of an additional, non-heme redox center can explain how SoxAX can store the two electrons that are released during its reaction (12); however, it does not explain the role of the SoxA heme cysteine ligand in catalysis or how it could become modified to a persulfide form.

In this paper, we have explored this issue by investigating the structural, physical, and kinetic changes in SoxAX properties associated with a substitution of the heme-ligating cysteine residue. As part of this work, the first crystal structure for both the wild type and substituted group2 SoxAX protein were solved and provide unique insights into the structural changes underlying the catalytic and spectroscopic properties of SoxAX cytochromes.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Bacterial Strains and Growth Conditions

Escherichia coli strains S17-1 (15) and DH5α (Invitrogen) were routinely grown on liquid or solid LB medium at 37 °C (16); for Rhodobacter capsulatus strains, TYS (17), or RCV medium (18) and incubation at 30 °C were used. R. capsulatus was grown either anaerobically under phototrophic conditions or aerobically in the dark using shake flasks. Where appropriate, media were supplemented with antibiotics (given in μg/ml; numbers in parentheses refer to R. capsulatus): ampicillin 100 (−), tetracycline 10 (1), and gentamicin − (4).

Expression and Purification of Recombinant Proteins

SoxAX proteins from S. novella were expressed in R. capsulatus and purified as described (14); SoxYZ from S. novella was expressed in E. coli and purified as described (12).

Generation of a Site-directed Mutation in SoxAX

A mutation in the heme-ligating cysteine, Cys236, was created using primers SOXAC236MF (CAC CGC ATG TGG GAC ATG TAC CGC CAG ATG CGC) and SOXAC236MR (GCG CAT CTG GCG GTA CAT GTC CCA CAT GCG GTG). Mutagenesis was performed using the pDorex-SoxAX plasmid (14) as the template essentially as described (19). Inserts carrying the mutation were identified by sequencing followed by subcloning into pRK415 and transfer into R. capsulatus as in Ref. 14.

Protein Characterization Methods

SDS-PAGE was performed according to the method of Ref. 20; in-gel heme stains used the method of Ref. 21. Protein concentrations were determined using either the BCA-1 kit (Sigma-Aldrich) or the 2D-Quant kit (GE Healthcare). Mass fingerprints of proteins separated on SDS-polyacrylamide gels were prepared as in Ref. 7 and analyzed using a VoyagerSTR MALDI-TOF mass spectrometer (Applied Biosystems). Electrospray mass spectrometry was performed on a Q-Star mass spectrometer (Applied Biosystems) essentially as in Ref. 7. Molecular mass determination of native, purified proteins by multiangle laser light scattering was carried out as in Refs. 22 and 23. A sample volume of 50 μl of an ∼200 μm protein solution was used per injection, and experimental errors are reported as S.D. of the molecular mass estimate. Copper loading of purified SoxAX was carried out as in Ref. 12; metal content analysis of purified proteins was carried out using ICP-MS at the ENTOX Centre (University of Queensland); the heme content of recombinant SoxAX proteins was determined using alkaline hemochrome spectra as in Ref. 24. Mass Spectra of whole proteins and tryptic digests were collected at the School of Chemistry and Molecular Biology Proteomics facility. Modification of SoxYZ by sulfur compounds was tested using 30 μm protein samples and a 5 mm concentration of each sulfur compound, and the experiments were conducted at room temperature and 37 °C for 1 h before analysis using mass spectrometry. Thiol content of treated preparations was estimated using the method of Ref. 25.

Heme redox potentials were determined by optical redox potentiometry essentially as in Ref. 12. All potentials have been corrected relative to NHE. The experiments employed 5 μm enzyme solutions in 20 mm Tris buffer (pH 8.0), and the solution potentials were stabilized using high potential iron complexes as mediators (26). Changes in the electronic absorption spectrum were monitored continuously with an Ocean Optics USB4000 fiber optic spectrometer. A global analysis of the spectra was performed with the program SPECFIT/32 (Dr. R. A. Binstead, Spectrum Software Associates, Marlborough, MA) for a three-component model (Fe(III)/Fe(III), Fe(III)/Fe(II), and Fe(II)/Fe(II)) comprising two consecutive single electron redox reactions.

Assays determining the reduction of SoxAX by SoxYZ (12) used 10 μm SoxAX in 20 mm Tris-Cl, pH 8.0, and a 6:1 ratio of purified SoxYZ to SoxAX. All SoxYZ samples were stored in the presence of reductant (DTT; 5 mm), which was removed from the sample immediately prior to use by passing it through a PD-10 column (GE Healthcare). Electronic absorption spectra (300–700 nm) of the reaction mixture were recorded every 2 min using a Cary50 spectrophotometer (Varian). Kinetic assays contained 20 μm horse heart cytochrome c (Sigma-Aldrich catalog no. C7752), 20 mm MES, pH 6.0, or 20 mm Tris-Cl, pH 7.0, and reduced glutathione (final concentration 0.15–2 mm; standard assays used 1 mm), from a stock solution titrated to pH 7.0 as described (12). Assays using SoxYZ contained 20 mm MES, pH 6.0, 300 μm thiosulfate, 38.5 μm cytochrome c, and 4.85 μm reduced SoxYZ. Reduced SoxYZ refers to SoxYZ protein where the cysteine is detectable by 5,5′-dithiobis(nitrobenzoic acid)-based thiol assays. In both cases, reduction of cytochrome c was monitored at 550 nm, and data were fitted to the Michaelis-Menten equation using SigmaPlot (Sysstat Inc.) or IGOR Pro (WaveMetrics Inc.).

MCD Spectroscopy

MCD spectroscopy was carried out as described (27). Samples contained 20 mm Tris-Cl, pH 8 (samples for the IR were prepared in deuterium oxide) and 60% (v/v) glycerol as a glassing agent. Protein concentrations of 25 and 100 μm were used for the visible and infrared regions, respectively.

EPR Spectroscopy

Continuous wave X-band EPR spectra were recorded as in Ref. 12.

Crystallization and Data Collection

Conditions for the crystallization of SnSoxAX (32 mg/ml) were screened at 293 K according to the sparse matrix method (28) using commercially available screens. Screens were set up in 96-well plates (F-bottom Microplates, Greiner) using a Mosquito nanoliter liquid-handling robot (TTP LabTech). Equal volumes of protein (100 nl) and reservoir were mixed. Initial crystals were observed in condition 77 of the index screen (Hampton Research, 25% PEG 3350, 0.2 m lithium sulfate, 0.1 m Tris-Cl, pH 8.5). Crystal optimization trials were then performed in 24-well plates by varying the concentration of precipitant (PEG 3350, 24–29%) and the pH (0.1 m Tris-Cl, pH 8.3–8.9). In addition, an additive screen (Hampton Research) was carried out to improve the diffraction properties of the SnSoxAX crystals. The best crystals were grown in PEG 3350 (25%), lithium sulfate (0.2 m), Tris-Cl (0.1 m, pH 8.5), and spermidine (0.01 m) at 25 °C (298 K). The crystals reached maximum size in 3 weeks. Prior to x-ray data collection, crystals were quickly transferred into mother liquor containing 30% glycerol and frozen in a cold nitrogen stream (100 K). Data were collected using a Mar 345 image plate detector at either BM14 or ID29 at the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility or with copper Kα X-rays from a Rigaku RU-200 rotating anode generator focused using Osmic mirror optics. All data were processed and scaled with DENZO and SCALEPACK (HKL program suite) or with HKL2000. As prepared, SoxAX contains ∼10–20% copper. Crystals of copper-loaded SoxAX protein were obtained but failed to diffract. Similarly, soaking of SoxAX crystals in CuSO4 solution resulted in crystals with insufficient diffraction properties.

Structure Solution and Refinement

The structure of SoxAX was solved by multiple wavelength anomalous dispersion using data collected at the iron K-edge. Two data sets were used in the structure solution: a peak data set and a remote data set (collected at 1.739 and 0.954 Å, respectively). The peak data set was used to determine the positions of 8 iron atoms/asymmetric unit using SHELXD (29). Phases were calculated with both peak and remote data sets using SHARP (30) to the resolution limit of the remote data (2.20 Å). The automatic density modification protocol within autoSHARP (using DM and SOLOMON (31)) yielded an interpretable electron density map. Model building was carried out automatically with ARP/wARP (31, 32). Further model building was carried out manually in COOT (33). This structure was used to determine the positions of three SoxAX heterodimers in the asymmetric unit of a high resolution, native data set (1.77 Å, SnSoxAX in supplemental Table S1) by molecular replacement with PHASER (34). All three copies of SoxAX in the P1 asymmetric unit are identical within experimental error (r.m.s. deviation of 0.3–0.6 Å for the superposition of SoxA residues 46–274 and SoxX residues 40–208).

Refinement of the native structure was carried out with REFMAC5 (35), with manual adjustments incorporated in COOT. Tight NCS restraints were maintained throughout the refinement process until the final cycle, where they were removed completely. The structure of the C236M mutant protein (SnSoxAXC236M; supplemental Table S1) was solved by molecular replacement using the coordinates of the native SnSoxAX structure as a search model. Refinement and model building were carried out as for the native SnSoxAX structure, with the addition of twin refinement in REFMAC5. For all structures, water molecules were incorporated into the models automatically with ARP/wARP and later confirmed manually by inspection of electron density maps in COOT, with consideration of conservative hydrogen-bonding criteria. Residue numbering for all structures is based on the sequence of the unprocessed protein (accession number Q7BQR6).

RESULTS

Crystal Structure of the S. novella SoxAX Protein

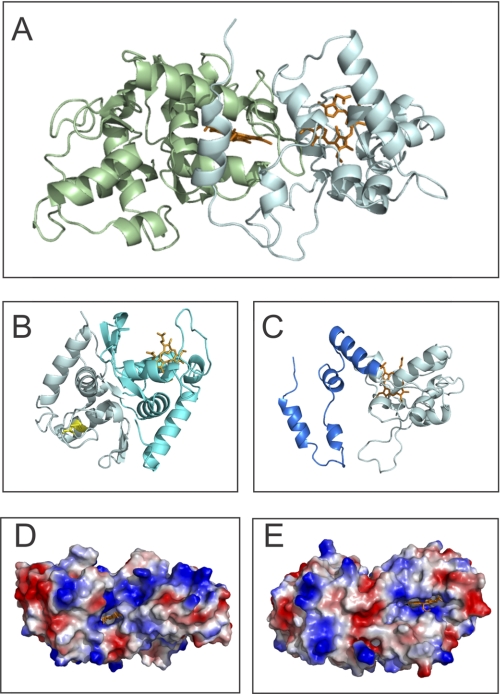

Three different groups of SoxAX proteins are known to exist, and while the structure of two representatives of the group 1, triheme SoxAX proteins from Rhodovulum sulfidophilum (RsSoxAX, Protein Data Bank code 2OZ1) and Paracoccus pantotrophus (PpSoxXA, Protein Data Bank code 2C1D) have been solved previously (8, 9), we have solved the first structure for a group 2, diheme SoxAX protein. SoxAX from S. novella (SnSoxAX) crystallized in space group P1 (1.77 Å resolution) with three heterodimers per asymmetric unit (supplemental Table S1). Similar to what has been described for the group 1 SoxAX structures, the SnSoxA subunit (A46–A274) can be divided into two structurally similar domains, A46–A152 and A153–A274, (r.m.s. deviation of 1.86 Å, superposition of 84 aligned Cα atoms) which introduces a pseudo-2-fold symmetry to this subunit (Fig. 1 and supplemental Fig. S1). Although RsSoxA and PpSoxA are diheme proteins, the single heme prosthetic group found in SnSoxA is coordinated by HisA187 and residue A236 (discussed below), while a disulfide bridge between CysA74 and CysA110 replaces the second heme group, thus confirming earlier observations using mass spectrometry (6, 7). Surface loops with different relative conformations (residues A187–A207 and A65–A86, respectively) border the SnSoxA heme group and the disulfide bond. The heme loop has an open conformation that “covers” the heme cofactor, while the disulfide loop reaches in toward the core of the molecule, filling the space created by the absence of the heme group (Fig. 1B). In contrast, both the RsSoxA and PpSoxA proteins show open loop structures about both heme-binding sites.

FIGURE 1.

Structure of the SnSoxAX. A, overall structure of SnSoxAX. Green, SnSoxA; gray, SnSoxX; orange, heme groups. B, domain structure of SnSoxA. Turquoise, domain 1; gray, domain 2; orange, heme group; yellow, disulfide bond. C, structure of SnSoxX. Gray, heme-binding core; blue, N-terminal extension. D and E, electrostatic surface of the SnSoxAX dimer. Both the SoxA (D) and SoxX (E) hemes are solvent-exposed. E shows the SoxAX dimer rotated by 180° around the horizontal (x) axis.

The SnSoxA heme ligand, residue A236, has been modeled as an equal mixture of Cys and the post-translationally modified cysteine persulfide (supplemental Fig. S2) residues as a result of careful analysis of difference Fourier electron density maps for a variety of models and occupancy refinement with PHENIX (36). Using this refinement, the average coordination distances for the three SnSoxA molecules in the asymmetric unit are as follows: HisA187 NE2-Fe = 2.1 Å; cysteine persulfide A236 SD-Fe = 2.3 Å; CysA236 SG-Fe = 2.5, with a bond length error of ∼0.15 Å.

The SnSoxX Subunit

The SnSoxX structure (residues B29–B208) can be partitioned into a tightly folded heme-binding domain (residues B96–B208) and an N-terminal extension (residues B29–B95) that is unique to group 2 SoxAX proteins. SnSoxX contains a single heme cofactor that is bound by a CXXCH motif (residues B125–129) and is axially ligated by residues HisB129 and MetB187 (HisB129 NE2-Fe = 2.09 Å; MetB178 SD-Fe = 2.36 Å).

The core of the SnSoxX model (residues B96–B208) can be superposed on the corresponding subunit structures of RsSoxX (Protein Data Bank code 1H33, 92 aligned residues, r.m.s. deviation of 1.6 Å) and PpSoxX (Protein Data Bank code 2C1D, 90 aligned residues, r.m.s. deviation of 1.5 Å) (Fig. 1 and supplemental Fig. S1). However, the mature SnSoxX protein is 70 residues longer than its homologues, and most of that difference lies in the SnSoxX N-terminal extension (B29–B95) as well as in some loop structures (e.g. RsSoxX B97–B119 and SnSoxX B109–B121) that are unique to each protein (Fig. 1 and supplemental Fig. S1).

The SnSoxX N-terminal extension (B29–B95) is tethered to the heme-binding domain through a disulfide bridge (CysB64–CysB175) and three hydrogen-bonding interactions between the N-terminal extension and the main body of SnSoxX (ArgB54–GlyB111; AspB58–ArgB180; ThrB60–GluB83). The N-terminal extension shows no significant structural homology to domains of proteins deposited within the PDB, and it is unlikely that it represents an independently folded domain. Because the N-terminal extension mediates a significant portion of the interactions between SnSoxX and SnSoxA, its structure may depend on these interactions.

The SnSoxAX Dimer

The SnSoxAX heterodimer has approximate dimensions of 70 × 35 × 35 Å (Fig. 1 and supplemental Fig. S1), with a buried surface area of ∼2100 Å2 per monomer (19%) and a shape complementarity statistic of 0.75, in keeping with values from other known permanent heterodimeric complexes (37). The interactions are mediated mainly by an association of the N-terminal extension structure of SnSoxX (residues B29–B95) with a helix and two loops from the SnSoxA subunit (residues A158–A174, A174–A183, and A241–A250) as well as some loop structures (supplemental Table S2).

In contrast, the RsSoxAX and PpSoxXA structures only have buried surface areas of ∼1500 Å2 per monomer (∼16% per subunit). The larger interface for SnSoxAX presumably translates to greater stability of the heterodimer as a whole.

The active site of SoxAX proteins is located at the interface of the two subunits, where the two heme cofactors of SnSoxAX are located. The edge-to-edge separation of the heme cofactors (distance between thioether groups) is 5.9 Å (Fe-Fe distance, 19 Å), and they have solvent-accessible areas of 86 and 113 Å2, respectively, which include the heme propionate groups (Fig. 1). The thioether groups of the heme cofactors point toward each other across the dimer interface; in fact, association of SnSoxAX in the dimer reduces the solvent-accessible area of the SnSoxX heme from 144 Å2 (SnSoxX subunit only) to 113 Å2 (SnSoxAX dimer).

The SnSoxAXC236M Cysteine Ligand Mutant

The cysteine ligand to the SnSoxA heme has been proposed to play a crucial role in catalysis by providing an intermediate binding site for substrate molecules, such as thiosulfate (8). Breakdown of the thiosulfate-SoxA complex without turnover has been postulated to lead to the persulfide modification of this cysteine observed in all available crystal structures of SoxAX proteins (8, 9). In order to investigate the importance of this residue for catalysis, we have created a substitution of this cysteine, C236M, in the SnSoxAX protein. If this cysteine residue is a key component in the SoxAX reaction, in the SnSoxAXC236M-substituted protein, catalysis should be impaired, and the spectroscopic signature of the protein should be less complex because the substituted enzyme contains only two His/Met-ligated heme groups.

The substituted protein, SnSoxAXC236M, contained a full complement of redox cofactors (1.9 heme groups/molecule), and both subunits could be stained for heme-linked peroxidase activity (data not shown). SnSoxAXC236M was also capable of binding ∼1.2 eq of copper/molecule, which is comparable with what was observed for SnSoxAXWT (12).

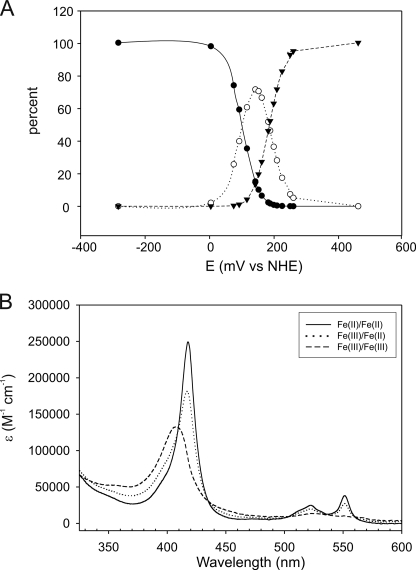

By a global analysis of the spectra obtained during optical redox titrations of SnSoxAXC236M (supplemental Fig. S3), the redox potentials of the two hemes were determined to be E1 = 162 ± 12 mV and E2 = 85 ± 15 mV, which is within the range expected for His/Met-ligated heme groups (38). Because E1 is rather close to the value previously determined for the SnSoxX heme group (12), we have tentatively assigned this potential to the SnSoxX heme. The spectra of the diferric, ferric/ferrous, and diferrous SnSoxAXC236M were also obtained as a result of the global analysis (Fig. 2), with the intermediate ferric/ferrous SnSoxAXC236M displaying a Soret band (417 nm) with approximately half the intensity of the diferrous form. Lowering the solution potentials of SnSoxAXC236M below −400 mV did not result in any further changes to the electronic absorption spectrum (data not shown).

FIGURE 2.

A, speciation diagram for the three redox forms of the protein. Black circles, ferrous spectrum; open circles, ferrous/ferric spectrum; triangles, ferric/ferric spectrum. B, deconvoluted spectra of the three redox forms from global analysis of the potential dependent spectra. The redox potentials are as follows: E1 = 186 ± 14 mV and E2 = 103 ± 18 mV. See also supplemental Fig. S1.

Structural Implications of the SnSoxAXC236M Substitution

SnSoxAXC236M crystallized in space group P1, with two heterodimers per asymmetric unit, and the refinement converged with residuals r = 0.251 and Rfree = 0.314 for all data to 2.25 Å resolution (supplemental Table S1). In the SnSoxAXC236M SoxA subunit (A46–A274), the heme cofactor is coordinated by residues HisA187 and MetA236, while heme coordination for the SoxX subunit (B30–B208) is unchanged.

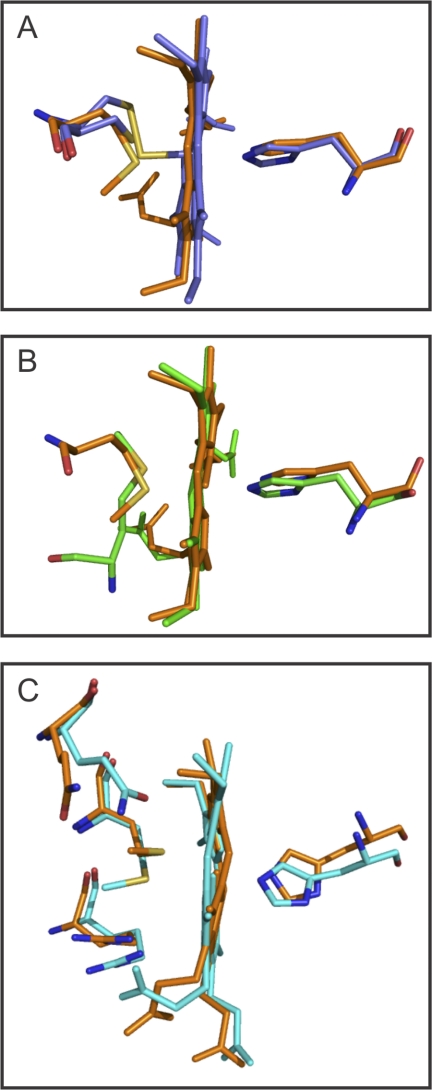

Superposition of the SnSoxAXC236M and SnSoxAXWT structures (chains A and B only, r.m.s. deviation of 0.75 Å for 414 Cα positions) shows that structural differences are confined to the N and C termini of the respective molecules, and only negligible adjustment of the surrounding polypeptide structure has accompanied the substitution of residue A236. In fact, the structure of Met236 is clearly constrained by the surrounding polypeptide, and analysis of the conformation of the Met236 ligand (33) revealed it to be a relatively uncommon rotamer, occurring in only 3% of protein crystal structures. Further comparisons revealed that although the His ligands and heme cofactors of the two SnSoxAXC236M heme groups overlay well between the two subunits (Fig. 3), the polypeptide structures harboring the Met ligands are completely different. This is also reflected in the coordination distances of the heme ligands. For the SnSoxAXC236M SoxA subunit, these are HisA187 NE2-Fe = 2.4 Å, MetA236 SD-Fe = 2.56 Å, HisC187 NE2-Fe = 2.1 Å, and MetC236 SD-Fe = 2.9 Å, while SoxX subunit distances of HisB129 NE2-Fe = 2.1 Å, MetB178 SD-Fe = 2.4 Å, HisD129 NE2-Fe = 2.1 Å, and MetD178 SD-Fe = 2.6 Å with a bond length error of ∼0.2 Å were observed. These data clearly show that differences between the general structures of the heme environments in the two heterodimers in the SnSoxAXC236M asymmetric unit exist.

FIGURE 3.

Comparison of the ligand environment of SnSoxAXWT and SnSoxAXC236M heme groups. A, comparison of SoxA active site hemes of SnSoxAXWT and SnSoxAXC236M. B, comparison of the SoxA and SoxX hemes of SnSoxAXC236M chains A and B. C, overlay of SnSoxAXC236M SoxA hemes chain A and chain C. Blue, SnSoxAXWT SoxA heme; orange, SnSoxAXC236M chain A SoxA heme; green, SnSoxAXC236M chain B SoxX heme; turquoise, SnSoxAXC236M chain C SoxA heme.

In addition to revealing the differing Met236 to iron bond lengths, the superposition of the SoxAC236M heme groups (chains A and C) shows that the relative orientations of the His and Met ligands differ (Fig. 3). In chain A, the planes of the two ligands are close to perpendicular, while in chain C they are parallel. Orientations of the side chains of Arg232 and Gln239 and the heme propionate groups also differ in chains A and C, which further suggests that the heme environment in the SoxA subunit of SnSoxAXC236M has some inherent flexibility.

MCD Spectroscopy

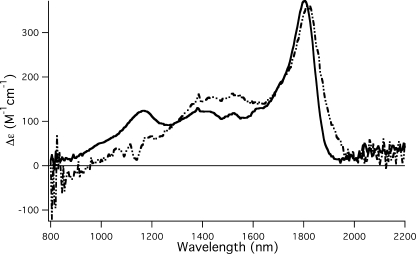

The UV-visible MCD spectra of SnSoxAXC236M show intense bands characteristic of low spin ferric heme, including a sharp negative feature at ∼690 nm characteristic of a sulfur to Fe charge transfer (CT) transition p(S) → dp(Fe) in His/Met ligated hemes (39, 40) that is also seen in SnSoxAXWT spectra (data not shown). In the 1000–2200 nm region, porphyrin to iron CT transitions with energies diagnostic of the axial ligation (41, 42) (Fig. 4) are located, and SnSoxAXWT spectra show two positive peaks that are due to the His/Cys (1150 nm) and His/Met (1800 nm) ligated heme species. Further broad positive intensity present in the 1350–1600 nm range has previously been assigned to the SoxA heme with a cysteine persulfide ligand (13). As expected, the 1150 nm peak is absent SnSoxAXC236M, while the 1800 nm peak remains; however, surprisingly, the intensity of the signals in the 1350–1600 nm region also remains. If this broad intensity were due to a cysteine persulfide ligated heme, then this intensity would be expected to decrease with the cysteine to methionine replacement. When reduced by dithionite, the MCD spectra of neither SnSoxAXWT nor SnSoxAXC236M showed these features. No evidence of a high spin ferric heme conformation of any of the hemes was apparent.

FIGURE 4.

Near IR MCD spectrum of SoxAXWT (solid line) and SoxAXC236M (dashed line) recorded at 2 K, 7 teslas with protein concentrations of 100 and 72 μm, respectively. Samples were buffered in 20 mm Tris-Cl, pH 8, and 60% glycerol in D2O. The SoxAXWT spectrum contains two main peaks corresponding to His/Cys (1150 nm) and His/Met (1800 nm) coordinated low spin heme groups, while the SoxAXC236M spectrum has a single main peak at 1800 nm, which is consistent with the mutation of Cys236 to methionine. The broad feature between 1300 and 1600 nm in the SoxAXWT spectrum was previously assigned to a His/Cys-persulfide ligated heme; however, the SoxAXC236M spectrum demonstrates the same broad feature, suggesting that this assignment needs to be reconsidered.

EPR Spectroscopy of SnSoxAXC236M

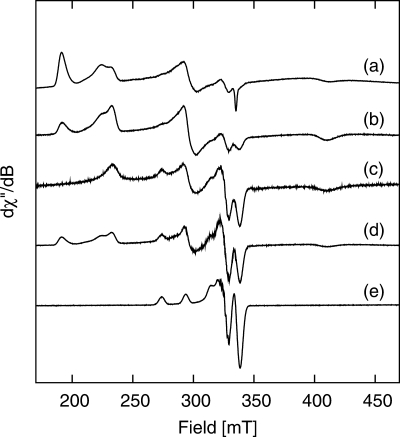

The published EPR data for both di- and triheme forms of SoxAXWT contain resonances from a type 3 His-Met low spin heme center (LS3 and SoxX) and multiple resonances (LS1a, -1b, and -2) from type 1 and 2 low spin His-Cys centers associated with the heme(s) in the SoxA subunit. The substitution of the SoxA heme-ligating cysteine Cys236 for a methionine was expected to simplify the properties of this heme group, including the EPR spectrum; however, the heterogeneity revealed by the x-ray crystallographic data above is also apparent in the EPR data (Fig. 5a). The EPR spectrum of SnSoxAXC236M reveals resonances at gmax ∼3.5 corresponding to the SnSoxX type 3 (LS3) heme observed in SnSoxAXWT and two major EPR active species (1 and 2, respectively) at g ∼(1.63, 2.25, 2.88) and g ∼(1.38, 2.30, 2.95) arising from the His/Met-ligated SoxA heme of SnSoxAXC236M (Table 1). In addition, at geff ∼4.3, resonances due to a small amount of adventitious Fe(III) are observed as well as a small amount of a type 3 heme signal (species 3) distinct from LS3 and an intense, slightly rhombically distorted high spin ferric heme signal, with geff = 2.000, 5.759, 5.980 (Fig. 5a and supplemental Fig. S4a). Resonances at ∼320 mT and the shoulder at ∼290 mT are due to Cu(II) and become relatively more intense as the temperature is raised to 50 K (Fig. 5, a–c). At 50 K, the EPR spectrum from species 1 persists, while those of species 2, 3, and LS3 disappear, indicating a fast spin lattice relaxation time (T1) for those heme centers. The SnSoxAXC236M high spin signal shows a slight rhombic distortion and can be simulated using the spin Hamiltonian parameters, D = 0.53 cm−1, E/D = 0.0045, g = 2.000 (supplemental Fig. S4b). The rhombicity of the high spin signal increases slightly when the protein is loaded with copper (Table 1).

FIGURE 5.

X-band EPR spectra of the “as prepared” SoxAXC236M and copper-loaded SoxAXC236M enzymes measured in 20 mm Tris-Cl buffer, pH 8, containing 50% glycerol. a, SoxAXC236M, T = 1.6 K, ν = 9.37520 GHz; b, SoxAXC236M, T = 8 K, ν = 9.37506 GHz; c, SoxAXC236M, T = 50 K, ν = 9.37501 GHz; d, copper-loaded SoxAXC236M, T = 1.6 K, ν = 9.37620 GHz; e, copper-loaded SoxAXC236M, T = 50 K, ν = 9.37494 GHz. The spectra have been scaled to ×5.36 (a, b, and e), ×21.43 (c), and ×2.68 (d).

TABLE 1.

The g values and ligand field parameters for the various heme signals in SnSoxAXWT and SnSoxAXC236M proteins

| gz | gy | gx | Δ/λ | V/λ | |V|/Δ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SnSoxAX | ||||||

| LS1a | 1.853 | 2.348 | 2.531 | 3.571 | 3.843 | 1.076 |

| LS1b | 1.835 | 2.348 | 2.556 | 3.541 | 3.631 | 1.025 |

| LS2 | 1.912 | 2.268 | 2.417 | 4.748 | 4.899 | 1.032 |

| LS 3 | 3.502 | |||||

| SnSoxAXC236M | ||||||

| 1 | 1.634 | 2.25 | 2.879 | 3.929 | 2.126 | 0.541 |

| 2 | 1.379 | 2.30 | 2.979 | 2.646 | 1.699 | 0.642 |

| 3 | 3.174 | |||||

| LS 3 | 3.495 | |||||

| 4a,b | 2.000 | 5.759 | 5.980 | |||

| Copper-loaded 4a,c | 2.000 | 5.762 | 5.993 | |||

a These g values are effective g values because they arise from a slightly rhombically distorted high spin ferric heme.

b D = 0.53 cm−1, E/D = 0.0045, g = 2.0.

c D = 0.53 cm−1, E/D = 0.0047, g = 2.0.

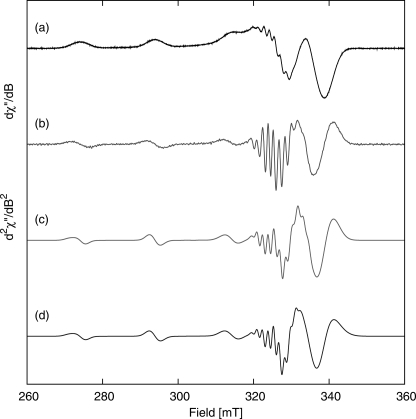

Similar to what has been reported for SnSoxAXWT (12), EPR spectra of SnSoxAXC236M (Fig. 5, a–c) reveal the presence of variable quantities of Cu(II). The first and second derivative spectra of copper-loaded SnSoxAXC236M (Fig. 6, a and b) reveal rhombic g and A matrices (supplemental Table S3) arising from a rhombically distorted Cu(II) center, and the second derivative spectrum shows ligand nitrogen hyperfine coupling (Fig. 6b). Simulation of the spectra assuming either three or four equatorially coordinated nitrogen nuclei does not allow us to distinguish between these different coordination spheres (supplemental Table S3 and Fig. 6, c and d); however, although the x and y components of the g and A(Cu, N) matrices are identical (supplemental Table S3), the value of gz (2.2028) for Cu-SnSoxAXC236M is smaller than for SnSoxAXWT (gz, 2.235), and Az is larger (202.63 × 10−4 cm−1) than for SnSoxAXWT (Az, 187.26 × 10−4 cm−1). Examination of the Blumberg-Peisach plots (43) reveals that either a change in the number of nitrogen nuclei coordinated to the Cu(II) ion or a change in the charge of the Cu(II) center could account for the observed differences.

FIGURE 6.

X-band EPR and power spectra of the Cu(II) center in SoxAXC236M recorded in 20 mm Tris-Cl at pH 8, 150 K, ν = 9.37560 GHz. Shown are the first (a) and second (b) derivative experimental EPR spectra. Shown are computer simulations of the second derivative spectra assuming ligand hyperfine coupling to either three (c) or four (d) nitrogen nuclei.

Impact of C236M Substitution on the SnSoxAX Reaction

SoxAX proteins are thought to catalyze the formation of a heterodisulfide bond between the carrier protein SoxYZ and a sulfur substrate (e.g. thiosulfate). SnSoxAXWT can be reduced by incubation with reduced SoxYZ, and using a 6:1 ratio of purified SoxYZ to SoxAX, a reduction rate of 0.042 μm/min was obtained for SnSoxAXC236M at pH 8.0, which is comparable with the 0.048 μm/min observed for SnSoxAXWT under similar conditions (12). This indicates that despite the removal of the cysteine from the active site, SnSoxAXC236M can still interact with SoxYZ.

Using an in vitro SoxAX assay system that uses reduced glutathione as the sulfur substrate and cytochrome c (horse heart) as an electron acceptor and leads to the formation of oxidized glutathione (12), the kinetic parameters for SnSoxAXC236M and SnSoxAXWT were determined at pH 6. Turnover of SnSoxAXC236M was reduced relative to the wild type enzyme (2.0 ± 0.5 s−1 instead of 3.7 ± 0.3 s−1 for SoxAXWT), while the apparent Km glutathione stayed the same within experimental error (228 ± 27 μm instead of 195 ± 12 μm for SoxAXWT). As a result, the second order rate constant, kcat/Km glutathione apparent is reduced to about 50% of the SnSoxAXWT value. The data clearly show that despite the absence of the active site cysteine, SnSoxAXC236M is still catalytically active, indicating that Cys236, although not crucial for SoxAX function, is still involved in the SoxAX reaction and promotes enzyme turnover.

We then aimed to develop an assay system that uses the natural substrates of SoxAX, SoxYZ, and thiosulfate and horse heart cytochrome c as the electron acceptor. In order to develop this system, it was first necessary to characterize the SnSoxYZ protein because SoxYZ from P. pantotrophus (PpSoxYZ) has been reported to undergo formation of higher order oligomers (44, 45) and has also been shown to be modified and activated to varying extents by incubation with reduced sulfur compounds (45, 46). In contrast to PpSoxYZ, which contains additional cysteine residues in the SoxZ subunit, the only cysteine residue present in SnSoxYZ is the one located in the GGCGG active site motif. In the absence of reductant in the storage buffer, SnSoxYZ becomes inactive (determined by testing SoxAX reduction), and native gel electrophoresis showed that these preparations contained two protein bands (supplemental Fig. S5). Using multiangle laser light scattering, we were able to show that reduced samples of SnSoxYZ contained only a single, 29.97 kDa peak corresponding well to a SoxYZ heterodimer (molecular mass 16.254 kDa for SoxY6xHis and 12.017 kDa for SoxZ), while oxidized preparations contained approximately equal amounts of the SnSoxYZ heterodimer (30.34 kDa) and a SnSoxYZ heterotetramer (59.57 kDa) (supplemental Fig. S5). A complete transformation of SnSoxYZ to the heterotetrameric form upon oxidation was never observed, although oxidized preparations were completely inactive, suggesting that other modification to the SoxY active site cysteine may occur. However, mass spectra of both the oxidized and reduced SoxYZ had SoxY mass modifications of +33 and +50 Da, with the only difference between the two preparations being a +67 Da present in about 18% of the oxidized SoxY preparation.

Incubation of SnSoxYZ with a variety of sulfur substrates (thiosulfate, sulfide, sulfite, glutathione, and oxidized glutathione) showed that all preparations contained both unmodified SoxY protein and protein with a mass modification of +32 Da (sulfur atom), which in sulfide-treated fractions increased to 48%. Following incubation with thiosulfate, 31% of SoxY molecules showed the corresponding modification by +113 Da. Interestingly, although incubation with glutathione did not alter the modification spectrum or SoxY, fractions incubated with oxidized glutathione contained a small amount of glutathione (+306 Da, 17%)-modified SoxY.

In assays using the reconstituted Sox system, PpSoxYZ was reported to be most active following reduction with sulfide. In contrast, SnSoxYZ showed the highest activity in the SoxAX reduction assay following treatment with fresh DTT, while following treatment with either sulfide or thiosulfate, it showed lower reduction rates (48–63% decrease), even when increased amounts of SoxYZ were used in the assay (data not shown). It should be noted that activation of PpSoxYZ was tested using the reconstituted Sox complex (proteins SoxYZ, SoxAX, SoxB, and SoxCD) as opposed to just its activity toward SoxAX as was done here, so that the results are not fully comparable.

Following this characterization, SoxYZ was then incorporated into assay mixtures that contained thiosulfate and cytochrome c (horse heart) in 20 mm MES buffer, pH 6.0. Cytochrome c reduction by the assay components was tested and found to be well below the enzymatic rates observed in the presence of SoxAX (Table 2). For this assay, SoxYZ concentrations were expressed as SoxYZ in thiol form, as estimated using a 5,5′-dithiobis(nitrobenzoic acid)-based thiol assay. Enzymatic rates increased with increasing amounts of SoxYZ being added, with saturation being estimated to require concentrations in excess of around 10 μm SoxYZ thiol. Despite the fact that due to the relatively low purification yield of SnSoxYZ it could only be added in non-saturating amounts (4.86 μm), a difference of ∼30% in the activities was observed with SnSoxAXWT and SnSoxAXC236M, respectively, under otherwise identical assay conditions (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Reactivity of SoxAXWT and SoxAXC236M in a SoxYZ-based assay and assessment of relevant background reactions

The progress of the reaction was determined by monitoring the reduction of the cytochrome c at 550 nm. Concentrations of individual assay components are given in the table. X, the component was part of the assay mixture. −, the component was not used in the assay. ΔE550/min values for complete assay mixtures were corrected for the rate of cytchrome c reduction observed with all assay components other than a SoxAX protein present (0.003 ΔE550/min). NA, not applicable.

| Cytochrome c (38.4 μm) | Thiosulfate (300 μm) | Reduced SoxYZ (4.86 μm) | SoxAX (0.048 μm) | SoxAXC236M (0.048 μm) | Cytochrome c reduction rate (ΔE550/min) | Cytochrome c reduction rate (μm/min) | SoxAX activity (units/mg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X | X | − | − | − | 0 | 0 | NA |

| X | X | X | − | − | 0.003 | 0.14 | NA |

| − | − | X | X | − | 0.00085 | 0.04 | NA |

| X | X | X | X | − | 0.00824 ± 0.0015 | 0.39 ± 0.07 | 0.165 ± 0.021 |

| X | X | X | − | X | 0.0057 ± 0.0016 | 0.27 ± 0.08 | 0.114 ± 0.022 |

DISCUSSION

The crystal structures of the S. novella SoxAX protein and its variant are the first crystal structures available for the diheme, group 2 SoxAX enzymes; the two previously published SoxAX structures were both for group 1, triheme SoxAX enzymes. Despite the replacement of the second SoxA heme group with a disulfide bond, the SnSoxA subunit retains the pseudo-2-fold symmetry already described for the SoxA subunits of group 1 enzymes (8) without substantial changes in the subunit fold.

In contrast, significant differences exist in the fold of the SoxX subunit and in the nature of the subunit interface. SoxX subunits of group 2 SoxAX proteins all have an N-terminal extension of ∼70 amino acids that is absent in the group 1 SoxX subunits, and only the core of the SoxX fold is conserved between the two groups of SoxAX proteins. While the N-terminal extension of the SnSoxX subunit is unlikely to represent an independently folded domain, it mediates extensive interactions between the SnSoxA and SnSoxX subunits, which results in an increase in the buried surface area for SnSoxAX and may stabilize the SoxAX heterodimer. In the trimeric group of SoxAX proteins, an additional polypeptide, SoxK (also known as SAXB), is required to stabilize the SoxAX complex. SoxK has no sequence similarities to any structures available in the Protein Data Base, but an analysis of its primary structure using the program PHYRE (47) predicts a predominantly α-helical secondary structure. It thus may be possible that SoxK and the SnSoxX N-terminal domain assume similar structures and functions.

Similar to the group 1 proteins, the SnSoxA heme has histidine and cysteine axial ligands, and the latter is present as a mixture of cysteine and a cysteine persulfide, with an approximately equal distribution of the two forms (Fig. 1 and supplemental Fig. S2). Since its discovery by Bamford et al. (8), the origin of the cysteine persulfide ligand of the SoxA active site heme has been the subject of intense speculation, and it is still unclear how this modification arises and what its role in the SoxAX-mediated reaction is.

In order to investigate this, we have created a substitution in SnSoxAX that replaces the SoxA heme cysteine ligand with a methionine residue. The SnSoxAXC236M substituted protein contained a full complement of redox cofactors with redox potentials in the typical range for His/Met-ligated hemes, and MCD spectroscopy confirmed the absence of the His/Cys-ligated heme group. The crystal structure confirmed that no major structural perturbations occurred as a result of the substitution. However, instead of the expected simplification of the SnSoxAXC236M EPR spectra, an increase in the number of the observed SnSoxA heme-related species from three to four different EPR active species, including a high spin ferric heme species, is observed (Table 1). This latter finding was surprising because no evidence for this was found in MCD studies of the SnSoxAXC236M ligand environment, but it might be due to the lower intensity of MCD signals obtained for high spin hemes (48). Although the g matrices for EPR species 1 and 2 of SnSoxAXC236M do not match any previously published SoxAX EPR species, using the data in Table 1, it is possible to calculate the contributions of these species to MCD spectra using the empirical formula ECT = 3973 + 1322 (Eyz/λ) that has been determined for a large collection of hemes where histidine is one of the axial ligands and the other ligand is varied (41). The calculated ECT values are 1407 and 1597 nm for EPR species 1 and 2 of SnSoxAXC236M, respectively, indicating that these transitions may be responsible for the increased MCD intensity in the 1350–1600 nm region of the SnSoxAXC236M MCD spectrum (Fig. 4). This is consistent with the loss of these features upon dithionite reduction. Clearly, both the EPR and the MCD spectra show that the mutation of the SoxA heme to His/Met ligation results in an electronic structure very different from that of the His/Met-ligated SoxX heme. In particular, it does not result in a large gmax (type I) heme. The smaller ligand field parameters Δ, V in Table 1 imply that MetA236 has a smaller axial and rhombic ligand field on the t2g Fe(III) d-orbitals.

The unusual spectroscopic properties of the SnSoxAXC236M SoxA heme may be due to the inherent flexibility of this heme site, which is also demonstrated by the SnSoxAXC236M crystal structure, where the Met236 residue is present not only as an unusual rotamer but also in different orientations relative to the His ligand. Changes in ligand orientation are well known to influence the spectroscopic properties of heme groups and are a likely cause of the observed complex spectroscopic properties, including the unusual intensities between 1350 and 1600 nm in the near IR-MCD. The SnSoxAXC236M crystal structure also indicates that the bond distances of the SoxA heme ligands can vary significantly. In chain C, the Met SD-Fe distance is nearly 3 Å, and in view of this, it may be possible that additional forms of the SnSoxAXC236M SoxA heme exist in solution, in which the SoxA heme may be only five-coordinate, giving rise to the observed high spin EPR signal.

Careful analysis of the SnSoxAXWT crystal structure also shows small variations in the SoxA heme environment that may produce the observed heterogeneity of the LS1 EPR signal. In all three heterodimers, there is some variability of the Cys-Sγ to iron distances, and the angles of the histidine ring planes relative to the nearest Fe-N (heme) bond also varied (19.2–28.3°), while hardly any variability is observed for the SoxX heme.

Whether the heme environment structures observed in the SnSoxAXC236M crystal structure reflect distinct conformations in solution or the averages of many possible environments is unclear in the current structure due to limitations associated with the resolution and quality of the diffraction data. However, it is probable that the heterogeneity observed in the SoxAX EPR spectra is due to the overall structural flexibility of the site rather than being exclusively caused by the cysteine SoxA heme ligand and its modifications.

Previously, a critical role for the posttranslational cysteine persulfide modification of the SoxA heme ligand for SoxAX has been suggested, and this might also account for the flexibility of the SoxA heme coordination sphere because it would imply that sulfur substrates such as thiosulfate or possibly even the SoxYZ GGCGG sulfur binding motif could become temporarily bound to the Cys236 residue. However, in our current glutathione-based in vitro assay system, SnSoxAXC236M was still catalytically competent, although turnover was reduced by 45%. A second generation SoxAX in vitro assay based on SoxYZ and thiosulfate as sulfur substrates was developed, and this is the first available assay for an isolated component of the Sox multienzyme complex. This new assay confirmed the results obtained with the glutathione-based assay, with activities of SnSoxAXC236M being 30% lower than those of the wild type enzyme. These data show that although Cys236 participates in the SoxAX reaction, it is not absolutely crucial for SoxAX reactivity, making a purely rhodanese-like SoxAX reaction mechanism (8) unlikely. Interestingly, the dramatic change in the redox potential of the SnSoxAC236M heme appeared to have little if any influence on SoxAX catalytic competence. Our data suggest that the SoxAX reaction mechanism does not rely on the cysteine ligand to the SoxA heme as the center of heterodisulfide bond formation, and our newly developed SoxYZ-based assay opens up new possibilities of investigating SoxAX and site-directed SoxAX mutants for their catalytic properties.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. Glen King and Dr. Susan Rowland for making the multiangle laser light scattering system available for this project.

This work was supported by Australian Research Council Grant and Fellowship DP0878525 (to U. K.).

The atomic coordinates and structure factors (codes 3OA8 and 3OCD) have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ (http://www.rcsb.org/).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Tables S1–S3 and Figs. S1–S5.

- SnSoxAX

- S. novella SoxAX protein

- SnSoxA

- S. novella SoxA protein

- SnSoxX

- S. novella SoxX protein

- RsSoxAX

- R. sulfidophilum SoxAX protein

- PpSoxAX

- P. pantotrophus SoxAX protein

- CT

- charge transfer

- mT

- millitesla(s)

- MCD

- magnetic circular dichroism.

REFERENCES

- 1. Kappler U., Dahl C. (2001) FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 203, 1–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Friedrich C. G., Bardischewsky F., Rother D., Quentmeier A., Fischer J. (2005) Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 8, 253–259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Frigaard N. U., Dahl C., Robert K. P. (2009) Adv. Microb. Physiol. 54, 103–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dahl C., Schulte A., Stockdreher Y., Hong C., Grimm F., Sander J., Kim R., Kim S. H., Shin D. H. (2008) J. Mol. Biol. 384, 1287–1300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Omura T. (2005) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 338, 404–409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ogawa T., Furusawa T., Nomura R., Seo D., Hosoya-Matsuda N., Sakurai H., Inoue K. (2008) J. Bacteriol. 190, 6097–6110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kappler U., Aguey-Zinsou K. F., Hanson G. R., Bernhardt P. V., McEwan A. G. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 6252–6260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bamford V. A., Bruno S., Rasmussen T., Appia-Ayme C., Cheesman M. R., Berks B. C., Hemmings A. M. (2002) EMBO J. 21, 5599–5610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dambe T., Quentmeier A., Rother D., Friedrich C., Scheidig A. J. (2005) J. Struct. Biol. 152, 229–234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hensen D., Sperling D., Trüper H. G., Brune D. C., Dahl C. (2006) Mol. Microbiol. 62, 794–810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Reijerse E. J., Sommerhalter M., Hellwig P., Quentmeier A., Rother D., Laurich C., Bothe E., Lubitz W., Friedrich C. G. (2007) Biochemistry 46, 7804–7810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kappler U., Bernhardt P. V., Kilmartin J., Riley M. J., Teschner J., McKenzie K. J., Hanson G. R. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 22206–22214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cheesman M. R., Little P. J., Berks B. C. (2001) Biochemistry 40, 10562–10569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kappler U., Hanson G. R., Jones A., McEwan A. G. (2005) FEBS Lett. 579, 2491–2498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Simon R., Priefer U., Puhler A. (1983) Bio/Technology 1, 784–791 [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ausubel F. M., Brent R., Kingston R. E., Moore D. D., Seidman J. G., Smith J. A., Struhl K. (2005) in Current Protocols in Molecular Biology (Janssen K. ed) John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, NJ [Google Scholar]

- 17. Beringer J. E. (1974) J. Gen. Microbiol. 84, 188–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Weaver P. F., Wall J. D., Gest H. (1975) Arch. Microbiol. 105, 207–216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kappler U., Bailey S., Feng C., Honeychurch M. J., Hanson G. R., Bernhardt P. V., Tollin G., Enemark J. H. (2006) Biochemistry 45, 9696–9705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Laemmli U. K. (1970) Nature 227, 680–685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Thomas P. E., Ryan D., Levin W. (1976) Anal. Biochem. 75, 168–176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wilson J. J., Kappler U. (2009) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1787, 1516–1525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rowland S. L., Burkholder W. F., Cunningham K. A., Maciejewski M. W., Grossman A. D., King G. F. (2004) Mol. Cell 13, 689–701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Berry E. A., Trumpower B. L. (1987) Anal. Biochem. 161, 1–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Riddles P. W., Blakeley R. L., Zerner B. (1983) Methods Enzymol. 91, 49–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bernhardt P. V., Chen K. I., Sharpe P. C. (2006) J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 11, 930–936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kappler U. (2008) in Microbial Sulfur Metabolism, pp. 151–169, Springer, Berlin [Google Scholar]

- 28. Jancarik J., Kim S. H. (1991) J. Appl. Crystallogr. 24, 409–411 [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sheldrick G. M. (2008) Acta Crystallogr. A 64, 112–122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. delaFortelle E., Bricogne G. (1997) Macromol. Crystallogr. A 276, 472–494 [Google Scholar]

- 31. CCP4 (1994) Acta Crystallogr. D 50, 760–763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Langer G., Cohen S. X., Lamzin V. S., Perrakis A. (2008) Nat. Protoc. 3, 1171–1179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Emsley P., Cowtan K. (2004) Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 60, 2126–2132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. McCoy A. J., Grosse-Kunstleve R. W., Adams P. D., Winn M. D., Storoni L. C., Read R. J. (2007) J. Appl. Crystallogr. 40, 658–674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Murshudov G. N., Vagin A. A., Dodson E. J. (1997) Acta Crystallogr. D 53, 240–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Adams P. D., Afonine P. V., Bunkóczi G., Chen V. B., Davis I. W., Echols N., Headd J. J., Hung L. W., Kapral G. J., Grosse-Kunstleve R. W., McCoy A. J., Moriarty N. W., Oeffner R., Read R. J., Richardson D. C., Richardson J. S., Terwilliger T. C., Zwart P. H. (2010) Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 213–221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Jones S., Thornton J. M. (1996) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93, 13–208552589 [Google Scholar]

- 38. Frausto da Silva J. J. R., Williams R. J. P. (2001) The Biological Chemistry of the Elements: The Inorganic Chemistry of Life, pp. 370–399, Oxford University Press, Oxford [Google Scholar]

- 39. McKnight J., Cheesman M. R., Thomson A. J., Miles J. S., Munro A. W. (1993) Eur. J. Biochem. 213, 683–687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Spilotros A., Levantino M., Cupane A. (2010) Biophys. Chem. 147, 8–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Gadsby P. M. A., Thomson A. J. (1990) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 112, 5003–5011 [Google Scholar]

- 42. Thomson A. J., Gadsby P. M. A. (1990) J. Chem. Soc. Dalton Trans., 1921–1928 [Google Scholar]

- 43. Peisach J., Blumberg W. E. (1974) Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 165, 691–708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Quentmeier A., Li L., Friedrich C. G. (2008) FEBS Lett. 582, 3701–3704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Quentmeier A., Janning P., Hellwig P., Friedrich C. G. (2007) Biochemistry 46, 10990–10998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Quentmeier A., Friedrich C. G. (2001) FEBS Lett. 503, 168–172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kelley L. A., Sternberg M. J. E. (2009) Nat. Protoc. 4, 363–371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Cheesman M. R., Greenwood C., Thomson A. J. (1991) Adv. Inorg. Chem. 36, 201–205 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.