Abstract

Human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) is an important biomarker in pregnancy and oncology, where it is routinely detected and quantified by specific immunoassays. Intelligent epitope selection is essential to achieving the required assay performance. We present binding affinity measurements demonstrating that a typical β3-loop-specific monoclonal antibody (8G5) is highly selective in competitive immunoassays and distinguishes between hCGβ66–80 and the closely related luteinizing hormone (LH) fragment LHβ86–100, which differ only by a single amino acid residue. A combination of optical spectroscopic measurements and atomistic computer simulations on these free peptides reveals differences in turn type stabilized by specific hydrogen bonding motifs. We propose that these structural differences are the basis for the observed selectivity in the full protein.

Keywords: Antibodies, Circular Dichroism (CD), Fourier Transform IR (FTIR), Hormones, Molecular Dynamics, Human Chorionic Gonadotropin, Oncology

Introduction

The glycoprotein human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG),2 is a heterodimer consisting of an α- and β-chain (Fig. 1a) in noncovalent association. Essential in pregnancy and detectable within a few days of fertilization, it has become one of the most frequently assayed hormones, and simple, one-step, antibody-based measurements of hCG are now standard in pregnancy testing. At this early stage of pregnancy, the trophoblast cells of the preimplantation embryo produce a hyperglycosylated form of the hormone, which drives embryonic implantation in the uterine wall (2). Subsequently, hCG regulation by syncytiotrophoblast cells of the placenta promotes and maintains progesterone secretion from the corpus luteum. In other applications, therapeutically injected hCG is the key to in vitro fertilization, where it is used to trigger ovulation and, in males, used to promote testosterone production.

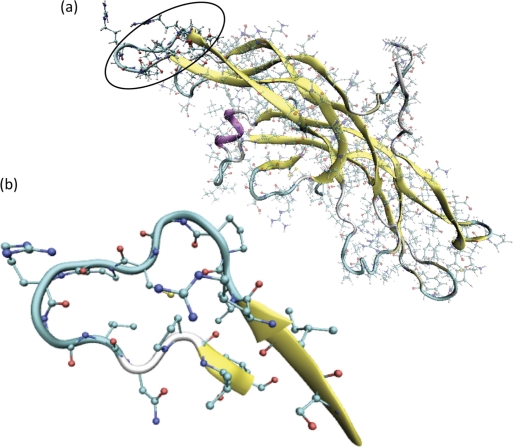

FIGURE 1.

a, crystal structure of hCG (1). hCGβ66–80 is circled. b, crystal structure of hCGβ66–80 as obtained from Protein Data Bank ID code 1HRP. Hydrogen atoms are omitted.

The role of hCG as a tumor marker in a variety of cancers is of great clinical significance (3, 4), and quantitative, specific hCG tests are important in the diagnosis and management of hCG-secreting cancers (5). However, the design criteria of hCG cancer assays differ from those required for pregnancy tests. Specifically, different sensitivity ranges are involved, and, for oncology applications, the antibodies used must be able to detect various modified forms of hCG with equal affinity (6). The role of hCG assays in the diagnosis and management of malignant trophoblastic disease (choriocarcinoma) is one of the great success stories of oncology (7, 8); it is the ideal tumor marker, always present when choriocarcinoma cells exist, and in quantities directly related to the number of those cells. The correct use of hCG assays in combination with appropriate therapy has led to a survival rate approaching 100% in this otherwise aggressive cancer.

All hCG diagnostic tests are carried out as immunoassays, based on specific antibodies that are able to distinguish hCG from three other, closely related, members of the glycoprotein hormone family (luteinizing hormone (LH), follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), and thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH)) (9). The α-chains of these four hormones are identical, each comprising 92 amino acids. The β-chains are hormone-specific and determine the particular activity of each hormone (10) but exhibit significant sequence homology among all four β-chains, with LH having 86%, TSH 46%, and FSH 36% commonality with the first 114 amino acids of hCG (11). Both the α- and β-chains are composed as three loops held in place by a “cysteine knot” of three disulfide bonds (1, 12).

These similarities in sequence and structure, especially within the quartet of the glycoprotein protein hormones (hCG, LH, TSH, FSH), make stringent demands of antibody specificity when immunoassays are used to distinguish among the different molecules. To ensure high fidelity in hCG detection and quantification, rigorous antibody characterization and selection are essential and, for this reason, much attention has been paid to hCG epitope structure as it relates to the specificity of antibody binding to the various hCG isoforms. The diagnostic value of any hCG immunoassay depends totally on the properties of the antibody around which the assay is built. Previous analysis of the hCG epitope structure (13) focused on the assignment of epitopes to the three-dimensional structure of hCG, together with a clear linkage to identified monoclonal antibodies.

However, a wide range of hCG variants exists, differing both in glycosylation state and fragment size (3, 14, 15). This heterogeneity poses a major obstacle to the development of a quantitative universal immunoassay for hCG (16), especially because many hCG epitopes depend on the molecule being intact and/or in its native conformation (11). An assay architecture built around a single epitope site is preferred because a two-site assay (double antibody sandwich) could result in more false negative results due to the doubled risk of one of the necessary epitopes being absent in a hCG variant (17). However, the performance of a single site assay depends on the identity and nature of the chosen epitope, and it is crucial that it is present, intact and correctly folded in every hCG variant encountered.

It is against this background that the β3-loop of hCGβ66–80 (Fig. 1b) has been identified as a potentially ideal epitope on which to base universal, single site hCG assays. This loop is present in all known variants of hCG, and we postulate that it might have its own, self-contained secondary structural features that are retained, regardless of the conformation or fragmentation state of the rest of the molecule. It is suggested here that this local structure provides the basis for antibodies against this epitope to bind with similar affinity to any known hCG variant, as long as the relevant linear sequence remains accessible.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Peptide Synthesis

Peptides were synthesized with Fmoc chemistry on TGA resin (Merck Chemicals) using a Liberty Microwave Synthesizer (CEM). Completed peptide resins were cleaved in 95% TFA (Rathburn), 2.5% water, and 2.5% trisopropylsilane (Sigma) for 2 h, and recovered TFA liquors were dried by rotary evaporation and precipitated in cold tert-butyl methyl ether (Sigma) to afford a white solid. Freeze-dried crude peptides were purified using a Dionex Ultimate 3000 HPLC system with an Onyx C18 column (Phenomenex) and a mobile phase gradient of 5% acetonitrile/water (0.1% TFA) to 100% acetonitrile (0.1% TFA) over 8 min. Pure peptide fractions were reduced by rotary evaporation and freeze-dried from 50% acetonitrile. Purified peptides were analyzed using a C18 kinetix column (Phenomenex). Integrated peak areas typically indicated purity of 95% or above. Peptides were positively identified by electrospray mass spectrometry (Waters ZMD MK II).

Screening Assays

A range of peptide arrays were synthesized on polypropylene 455-well PEPSCAN cards using standard Fmoc chemistry. Initially, to determine which linear sequential epitopes were recognized by various antibody preparations, a library of overlapping 12-mer peptides representing the entire sequence of hCGβ was created (18); the first well was endowed with an array of identical immobilized peptides consisting of amino acids 1–12, the second well carried peptides consisting of amino acids 2–13, the third 3–14, etc. In conjunction with further libraries constructed with longer peptides (up to 20-mer), these libraries were used to determine which host species (mouse, rabbit, or sheep) were able to produce antibodies that recognized the linear sequence of the β3-loop. From these findings a panel of candidate monoclonal antibodies with binding specificity for the β3-region was selected. These monoclonal antibodies were prepared by hybridoma techniques in the laboratories of Bioventix Ltd. (Farnham, UK). Subsequently, once the recognition of the correct sequential epitope (hCGβ66–80) had been confirmed, a positional scanning library incorporating all single natural amino acid changes across the peptide sequence SIRLPGCPRGVNPVV (of hCGβ66–80) was used. After deprotection with TFA and scavengers, the cards were washed extensively with an excess of H2O and sonicated in disrupt-buffer containing 1% SDS/0.1% β-mercaptoethanol in PBS (pH 7.2) at 70 °C for 30 min, followed by sonication in H2O for another 45 min. The binding of antibody to each peptide was tested in a PEPSCAN-based ELISA. The polypropylene cards containing the covalently linked peptides were incubated with primary antibody 8G5 (obtained from sheep) diluted in blocking solution, 4% horse serum, 5% ovalbumin (w/v) in PBS/1% Tween. After the wells had been washed, the peptides were incubated with a 1/1000 dilution of secondary antibody peroxidase conjugate for 1 h at 25 °C to detect and quantify the binding of 8G5 antibodies. After a further washing step, the peroxidase substrate 2,2′-azino-di-3-ethylbenzthiazoline sulfonate (ABTS) and 2 μl of 3% H2O2 were added. Color development was then measured by means of a charge-coupled device camera and an image processing system, after a 1-h incubation (19).

Sample Preparation

The peptides were dissolved directly in 10 mm phosphate buffer solution (pH 6.8), with a final concentration of 0.11 mm (0.177 mg ml−1). The peptides stock concentration was confirmed by UV-visible spectroscopy using a calculated extinction coefficient of ϵ214 = 21,807 m−1 cm−1 (20). For the samples with the fluorinated alcohol HFIP, water and 0.2 m buffer solutions were used to ensure the overall buffer concentration remained 10 mm.

Circular Dichroism (CD) Measurements

Far-ultraviolet CD spectra were recorded on a Jasco J-810 spectropolarimeter (Japan Spectroscopic Co., Tokyo) fitted with a Peltier unit for temperature control. The spectra are the average of three accumulations in step mode (data pitch of 1 nm, response time of 8 s, bandwidth of 1 nm) acquired in rectangular cuvettes of 0.1 cm path length (Hellma GmbH, Germany) at 20 °C. For every sample, an appropriate solvent spectrum was recorded under identical conditions and subtracted from the corresponding sample spectrum. The data collected was expressed in molar ellipticity (m−1 cm−1).

Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy

FTIR-attenuated total reflectance spectra were collected using a Tensor-37 FTIR spectrophotometer (Bruker Optics) equipped with a thermostatted BioATR II unit and a liquid nitrogen-cooled photovoltaic mercury cadmium tellurium detector. The spectra were analyzed using the OPUS software (Bruker Optics). Five acquisitions (128 scans, 4-cm−1 resolution) were done at different peptide concentrations. The contribution from atmospheric gases was eliminated using an algorithm provided by the OPUS software. The contribution of liquid water was subtracted from the peptide spectrum using the combination band of water, centered at 2125 cm−1, by flattening the region from 1906 to 1740 cm−1.

FTIR spectra of synthetic peptides should be analyzed carefully due to the possibility of trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) being present as an impurity in the sample, resulting from the reverse phase-HPLC purification step. It is important to consider TFA because it is known to absorb in the Amide I region at 1673–1680 cm−1 and can result in an overestimation of certain secondary structural elements (e.g. turns). To compensate for this, the TFA contribution is subtracted if the spectrum of a synthetic peptide presents a peak centered around 1200 cm−1 (21).

Computational Methods

An array of peptides was generated by performing point mutations on the structure of hCGβ66–80 obtained from Protein Data Bank ID code 1HRP (supplemental Fig. 1), varying only the coordinates of the side chain and not the backbone. From theses, unit cells were set up, which comprised a peptide sequence, 1853 water molecules and counterions to ensure charge neutrality (Table 1). The molecules were arrayed on a cubic lattice with random molecular orientations in a cubic box of length 38.2 Å. The rigid, nonpolarizable, three-site TIP3P empirical force field was used to describe the water molecules, the peptide was described by the CHARMM22 force field (22), and the PINY simulation package (23) was employed to perform the simulations.

TABLE 1.

Peptide sequences and counterions used in unit cells

| Peptide sequence | Counterions | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| SIRLPGCPRGVNPVV | 2 Chloride | supplemental Fig. 1 |

| SIRLPGCPRGVDPVV | 1 Chloride | |

| SIRLPGCPRGVHPVV | 2 Chloride | |

| SIRLPGCPRGVLPVV | 2 Chloride | |

| SIRLPGCPRGVGPVV | 2 Chloride |

The systems were equilibrated at 300 K in the canonical system for 350 ps with a time step of 0.5 fs to anneal out unphysical contacts. The system was then run for 300 ps with a time step of 0.5 fs in the isothermal-isobaric ensemble to allow for spatial relaxation. The system was then run for a further 150 ps in the canonical ensemble with a time step of 1 fs being employed before a production run of 15 ns using a time step of 2.5 fs from which all data were collected. Periodic boundary conditions were employed, and long range interactions were evaluated via Ewald summation.

To analyze the structure of the peptide using molecular dynamics simulations, we have made use of Ramachandran plots and bond probability distribution functions, as used by Samuelson et al. (24). The former allows for the assignment of secondary structure motifs based on dihedral angles while providing a clear illustration of the conformational space explored during the course of the simulation. The latter, on the other hand, allows for the probability distribution of selected atomic contacts as a function of interatomic separation to be assessed.

RESULTS

Relative Binding Affinity and Specificity

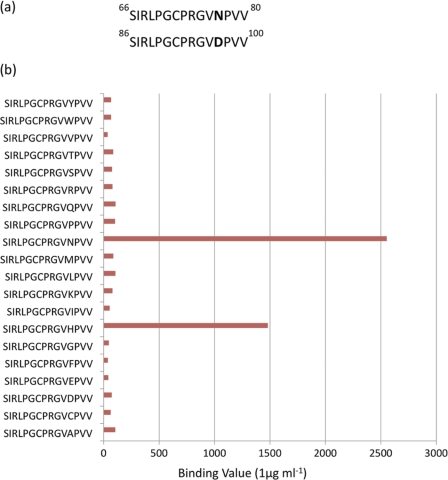

Of the three species tested, only sheep were found to produce antibodies to the β3-loop, with the loop appearing to constitute an immunodominant epitope. The sequence of the β3-loop is highly conserved with hCGβ66–80 and LHβ86–100 differing by only one amino acid; asparagine (Asn) in hCG cf. aspartate (Asp) in LH (Fig. 2a). Utilizing a particular sheep monoclonal antibody designated 8G5, point mutations in peptide arrays were introduced in the sequence SIRLPGCPRGVNPVV (hCGβ66–80) to determine whether substitution of the asparagine (Asn77) residue (Fig. 2b) had an impact on the antigen-antibody binding.

FIGURE 2.

a, primary structure of hCGβ66–80 (upper) and LHβ86–100 (lower). b, binding results from a small subset of the Pepscan positional substitution library, in which there is a systematic substitution of position 77, occupied by asparagine in hCGβ. Note that there is negligible binding to the peptide occupying the position third from the bottom, which equates to the sequence in LH. In the sequence containing histidine at position 77, the binding is ∼60% that of the hCGβ binding (supplemental Table 1).

We found that this single amino acid difference between LH and hCG confers a substantial specificity bias to the antigen-antibody interaction (Fig. 2), in favor of hCG with all five of the monoclonal antibodies binding to this region. Careful calibration of the LH cross-reactivity (with intact LHβ and hCGβ) revealed this to be 2.5% for 8G5 (additional antibodies were tested, and this cross-reactivity was found to range between approximately 0.27% and 2.5%). Substitution involving histidine (His) was the only other mutation found to retain significant binding. In view of the potential usefulness of this particular epitope-antibody combination, we explored the structure of the β3 epitope recognized so strongly by the ovine immune system by means of a combination of experimental techniques and computer simulation in the free peptide.

Additional point mutations were investigated, involving substitution of a proline (Pro78) residue (supplemental Table 2). The results revealed that binding to the monoclonal antibody 8G5 was lost.

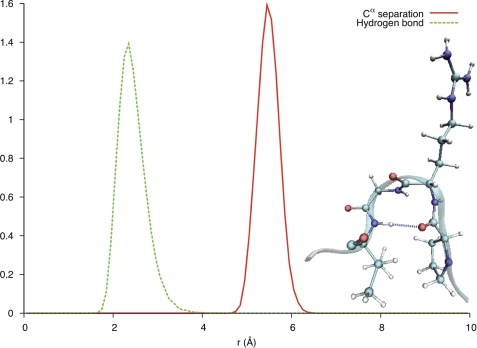

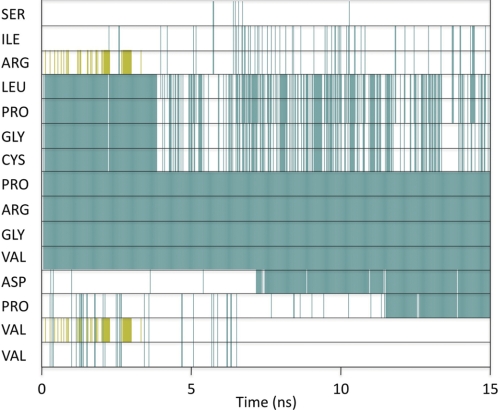

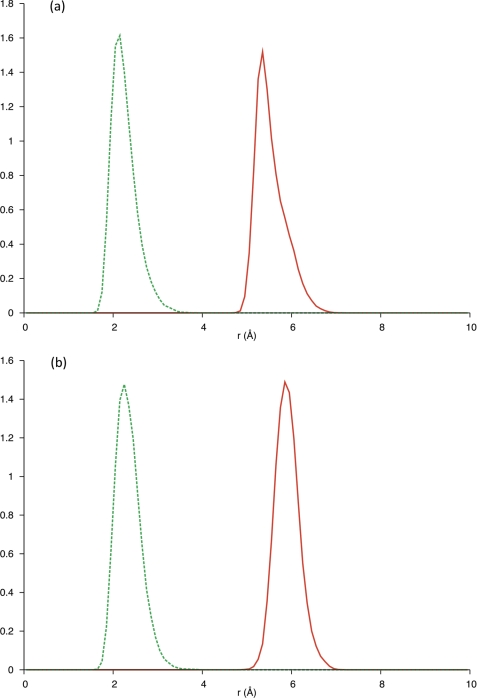

Secondary Structure of hCG

In the crystal structure of hCGβ, hCGβ66–80 is defined by two turns with β-sheet structure over the N and C termini (Fig. 1b) of the peptide. Molecular dynamics simulations were performed to reveal the structure of hCGβ66–80 under aqueous conditions (supplemental Fig. 2), to establish whether the structural features found in the crystalline subunit are retained in the free peptide. The secondary structure of each residue as a function of time was analyzed utilizing the STRIDE assignment algorithms (25) (Fig. 3). The simulation predicted a stable turn spanning the residues Pro73–Val76, persisting over the course of the 15-ns simulation. This was consistent with the separation of the Cα (α-carbons) of these residues, for which the distributions fell within the assumed 7-Å cutoff for a turn (Fig. 4). Furthermore, bond probability distributions revealed a peak below 2.5 Å for the backbone carbonyl group of Pro73 and the backbone amine group of Val76 (Fig. 4). This distance is assumed to define a hydrogen bond that contributes to the stability of the turn.

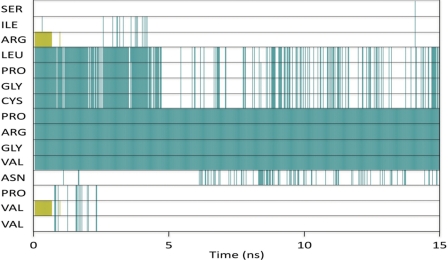

FIGURE 3.

Secondary structure of each residue of hCGβ66–80 as a function of time. Green corresponds to turn, white is unordered, and gold is β-strand. Simulation predicts a stable turn over Pro73–Val76, whereas a second turn spanning Leu69–Cys72 was found to be only a transient feature.

FIGURE 4.

Solid red line, separation of Cα in Pro73 and Val76. Dashed green line, separation between backbone carbonyl (Pro73) and amine (Val76) groups. Inset, visualization of the turn motif spanning residues PRGV (Pro73–Val76), revealing the stabilizing hydrogen bond between the backbone carbonyl group of Pro73 and the backbone amine group of Val76.

A second turn spanning Leu69–Cys72 present in the initial configuration became less ordered after 5 ns and returned only as a transient feature (Fig. 3). The STRIDE assignments were consistent with the separation of the Cα of Leu and Cys (supplemental Fig. 3a), with a notable portion of the distribution below the 7-Å cutoff. However, the corresponding hydrogen bond probability had a maximum at 3.66 Å (supplemental Fig. 3a), well above the 2.5-Å cutoff. This therefore ruled out the presence of a stabilizing hydrogen bond and may explain why the turn was only detected sporadically. Similarly, although the Cα separation between Asn77 and Val80 was below 7 Å, the corresponding donor and acceptor atoms were not within range for hydrogen bonding (supplemental Fig. 3b).

No evidence for other turn types such as γ-turns (supplemental Fig. 4), α-turns (supplemental Fig. 5), and π-turns (supplemental Fig. 6) in hCGβ66–80 was found. Specifically, no atom pair presented a peak below both the 7-Å and 2.5-Å cutoffs for Cα separation and hydrogen bond, respectively. Finally, evidence of β-sheet character in the full protein (present as an initial condition in the free peptide between Arg68 and Val79) was found to anneal away very quickly. This aspect of the full protein was therefore not retained in the isolated peptide.

The simulation therefore leads to a model of the free peptide in which a single stable turn coexists with other transient structures; more open and less structured than the sequence in the full β-chain. Direct experimental confirmation of such a dynamic situation is challenging, yet it is important to establish whether the simulations capture the general secondary structure of the free peptide.

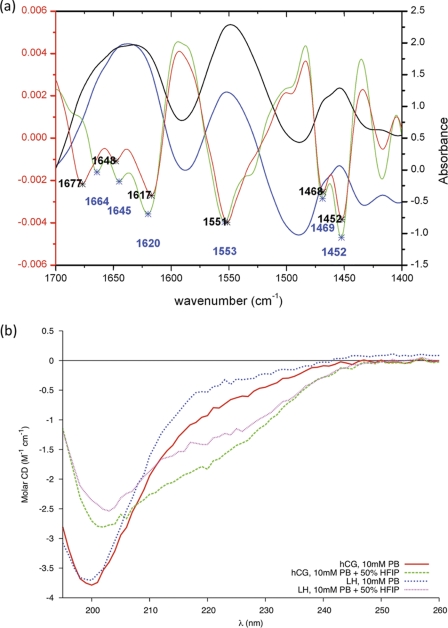

The measured FTIR spectra of hCGβ66–80 exhibited a broad Amide I band, indicative of the co-existence of different conformations in solution (Fig. 5a). Over the replicate measurements, the second derivative spectrum revealed bands consistent with the presence of a fractional population of turns in solution (26). The position of the Amide II band (maximum at 1551 cm−1) also suggested that β-turns were present because the band was positioned at a higher frequency compared with other structural elements (27).

FIGURE 5.

a, FTIR-attenuated total reflectance blank-subtracted and TFA-corrected spectrum of hCGβ66–80 (black), LHβ86–100 (blue), and their second derivative spectra (red and green, respectively) displaying the peak positions of the different components. b, far-ultraviolet CD spectrum of 0.11 mm hCGβ66–80 and 0.11 mm LHβ86–100.

The evidence for turns in the CD data is more equivocal; turns can give a variety of signatures with bands of positive or negative ellipticity at wavelengths of ∼200 nm. In particular, type II β-turns should exhibit a weak negative band at 220–230 nm, with a stronger positive band between 200 and 210 nm. Type I β-turns give CD spectra that are similar to those of an α-helix, characterized by positive ellipticity near 190 nm and two bands of negative ellipticity at longer wavelengths (28). None of these typical turn signatures was observed in the far-ultraviolet CD spectra of hCGβ66–80 (Fig. 5b). Instead, the single negative ellipticity band near 200 nm was more indicative of a disordered structure, and if turns were present they occurred as a minority component of an ensemble of open conformations.

To examine whether the conformational bias of the ensemble could be altered to enhance the population of a particular fold type, experiments were performed in fluorinated alcohol HFIP-water mixtures. Fluorinated co-solvents exclude water from the peptide environment, favoring the formation of intramolecular hydrogen bonds. Therefore, if a hydrogen bond is responsible for the stabilization of a particular conformation, a change in solvent conditions may shift the relative population of conformers. Far-ultraviolet CD spectra of hCGβ66–80 in 50% HFIP (v/v) were recorded (Fig. 5b). The presence of the Pro residues in the sequence of hCGβ66–80 would be expected to strongly disfavor the formation of a helical motif. Coupled with the structural preferences predicted by molecular dynamics, this observed change in the spectrum could be indicative of the stabilization of a turn motif. On the basis of these spectra, it was concluded that the secondary structure of hCGβ66–80 comprised an ensemble of open structures and turn motifs and that the simulated configurations (supplemental Fig. 2) were consistent with the experimental measurements.

Secondary Comparison between LH and hCG

Experimentally, the FTIR spectra of LHβ86–100 were similar to those observed in hCGβ66–80; namely, a broad Amide I band (Fig. 5a) was found from which the second derivative spectra were consistent with turns coexisting among other motifs (26). The Amide II band (maximum at 1553 cm−1) also suggested that β-turns were present (27).

The recorded far-ultraviolet CD spectra of LHβ86–100 (Fig. 5b) also revealed a predominantly disordered structure. There were, however, detectable differences between the hCG and LH spectra (∼220 nm) implying that the single point mutation had influenced the conformational equilibrium. Far-ultraviolet CD spectra of LHβ86–100 in 50% HFIP (v/v) also suggested the stabilization of a turn motif (Fig. 5b), although potentially to a lesser degree than observed for hCGβ66–80. The weaker shoulder of negative ellipticity at 220–230 nm may be due to LHβ86–100 presenting weaker intensity than hCGβ66–80 at these wavelengths in aqueous buffer. This may be indicative of hCGβ66–80 comprising more stable turn motifs than the LHβ86–100 mutant under such conditions.

Unsurprisingly, the main structural features of LHβ86–100 and hCGβ66–80 peptides were found to be similar, with each peptide comprising an ensemble of open structures and turn motifs. The experimental data, however, also revealed evidence of subtle differences arising from the point mutation, but precise secondary structure interpretation was beyond the resolution of the techniques employed. Because the molecular dynamics simulations and experiments of hCGβ66–80 were within the resolution limits of the measurements, further emphasis was placed on a secondary structure comparison based on the simulation evidence.

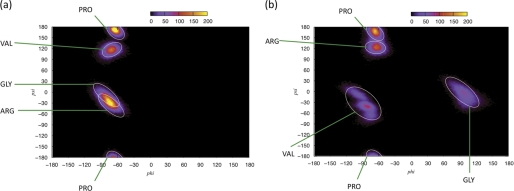

Molecular dynamics simulations were performed (Fig. 6) on the sequence found in the LH β3-subunit peptide (Fig. 2a) to identify whether the mAb 8G5 molecular recognition mechanism and selectivity between hCG and LH were due to a structural variation induced by the single amino acid mutation. Two main differences were found: First, although both peptides were defined by a β-turn over the PRGV span; Cα separation of Pro93–Val96 distributed around 5.365 Å, and bond probability analysis for stabilizing hydrogen bond revealed a peak positioned at 2.146 Å (Fig. 7a); the type of β-turn was different for each peptide. Ramachandran angles of Pro73–Val76 (hCGβ66–80) were calculated over the last 5 ns of the simulation (Fig. 8a). The two central amino acids were found to have angles (Arg: ϕ = −75, ψ = −30; Gly: ϕ = −85, ψ = −10) that indicated a type I β-turn, defined by the two central amino acids presenting angles of −60°,−30° and −90°,0°, respectively. The torsional angles of Pro93–Val96 (Fig. 8b), however, revealed that the two central amino acids (Arg: ϕ = −60, ψ = 120; Gly: ϕ = 90, ψ = 0) represented a type II β-turn (known to present torsional angles of −60°,120° and 80°,0°, respectively).

FIGURE 6.

Secondary structure of each residue of LHβ86–100 as a function of time. Green corresponds to turn, white is unordered, and gold is β-strand. Simulation predicts a stable turnover Pro93–Val96, with the span extending to include Asp97 and Pro98. A second turn spanning Leu89–Cys92 was found to be less stable.

FIGURE 7.

Solid red line, Cα separation. Dashed green line, separation between backbone carbonyl and amine. a, Pro93–Val96. b, Asp97–Val100.

FIGURE 8.

Ramachandran angles of sequence PRGV in hCGβ66–80 (a) and LHβ86–100 (b) over the last 5 ns. The torsional angles of the two central amino acids, Arg74 and Gly75, indicate a type I β-turn, whereas those for Arg94 and Gly95 indicate a type II β-turn.

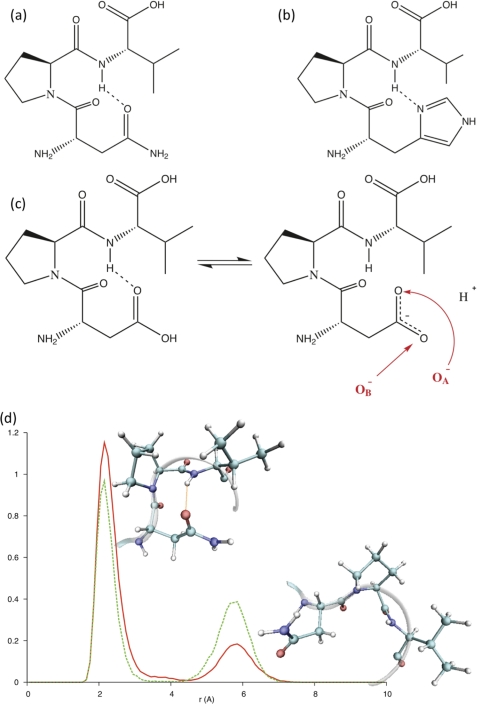

The second difference related to the presence of a specific hydrogen bond. Visualization of the crystallographic structure of the hCGβ subunit (supplemental Fig. 7) reveals a hydrogen bond between the carbonyl group of the Asn77 side chain and the backbone amine group of Val79 (Fig. 9a). It is known that asparagine can form hydrogen bonds with the polypeptide backbone, for example at the start or end of an α-helix or in turn motifs in β-sheets, and such a hydrogen bond could stabilize a hairpin loop whereby the peptide is “zipped” together at each end. The substitution involving histidine would also result in a similar orientation allowing for this hydrogen bond (Fig. 9b). It is also believed that although aspartate (native in LH) is very similar to asparagine (native in hCG), such a stabilizing hydrogen bond would only be present if Asp were protonated (Fig. 9c). This seemed surprising because one would have expected the deprotonated carboxylate anion to be a prime hydrogen bond acceptor. However, due to the deprotonation, the carbon and oxygens of the carboxylate anion would be partially sp and sp2 hybridized, respectively. This would lead to the formation of two partially double bonded C-O bonds, which could be spatially locked in an orientation disfavoring such an interaction.

FIGURE 9.

a–c, proposed H-bonding geometry in hCGβ66–80 (a), His77 mutant (b), and Asp77 mutant depicting the proposed “clasp” being only present in the protonated form of Asp (c). d, bond probability analysis of the safety catch in hCGβ66–80, coupled with visualizations of the structure corresponding to each peak.

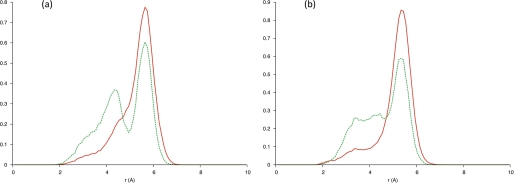

Bond probability distributions (Fig. 9d) revealed that irrespective of the chosen time frame, hCGβ66–80 presented two peaks at 2.158 Å and 5.852 Å, indicating only transient presence of this proposed hydrogen bond. Over the entirety of the LHβ86–100 simulation, bond probability distributions revealed a peak positioned at 5.662 Å for the O−A pairing (Fig. 10a), and a peak at 5.365 Å, with a shoulder at 3.357 Å for the O−B pair (Fig. 10b). These separations fluctuated to a greater degree over the last 5 ns, with the OA− pairing presenting a double peak at 5.662 Å and 4.367 Å (Fig. 10a), whereas the O−B pairing resulted in a peak at 5.365 Å accompanied by two (more pronounced) shoulders at 4.319 Å and 3.405 Å (Fig. 10b). The transient presence and separately, absence of such a hydrogen bond in these two systems would indicate that such a structural feature might be important in rationalizing the 8G5 discrimination between hCG and LH.

FIGURE 10.

Separation of Asp97 carboxylate oxygen (a) O−A, (b) O−B, and hydrogen of the backbone amine group of Val79. Solid red line, over full 15 ns. Dashed green line, over last 5 ns.

Other structural features of LHβ86–100 were the increase in span of the turn motif (Fig. 6), extended to include residues Asp97 and Pro98. Of potential β-turn Cα pairs that presented a peak below the assumed 7 Å threshold (supplemental Fig. 8), only Asp97–Val100 coincided with a stabilizing hydrogen bond (Fig. 7b). Visualization of the secondary structure (supplemental Fig. 9a) revealed that the sequence Pro93–Val100 appeared to comprise sequential β-turns forming an “S-bend ” motif. This second β-turn was found to present Ramachandran angles that indicated a type I β-turn (supplemental Fig. 9b).

Of all other potential turns, only the Pro93–Asp97 pairing presented peaks below the 7-Å and 2.5-Å thresholds for the Cα separation and hydrogen bond, respectively (supplemental Figs. 10–12). However, the strong evidence of two β-turns spanning this sequence precludes the presence of an α-turn.

Finally, evidence of β-sheet character between residues Arg88 and Val99 was found to anneal away more quickly than in hCG (Arg68 and Val79). However, it did return sporadically during the initial 3 ns of the simulation.

Other Mutations

Because the substitution involving histidine was the only such mutation found to retain significant binding to the mAb 8G5 (Fig. 2), a molecular dynamics simulation was performed on a sequence incorporating such a mutation (supplemental Fig. 13). The obvious major differences between the secondary structures was in the stability of the turn motif spanning residues Leu-Pro-Gly-Cys and in the β-sheet character between residues Arg and Val, with both structural motifs being more stable over the course of the 15-ns simulation.

The Ramachandran angles of the amino acids belonging to the sequence Pro73–Val76 (supplemental Fig. 14a) indicated a type I β-turn (Arg: ϕ = −75°, ψ = −30°; Gly: ϕ = −85°, ψ = −10°). As in the hCG model, analysis of the bond probability distributions of the suspected stabilizing hydrogen bond (supplemental Fig. 14b) revealed the presence of two peaks which persisted over the simulation, suggesting that the hydrogen bond was relatively stable.

Analysis of the models representative of the sequences SIRLPGCPRGVLPVV and SIRLPGCPRGVGPVV revealed the former to present a type II β-turn over the Pro-Arg-Gly-Val sequence (supplemental Fig. 15). SIRLPGCPRGVGPVV, however, was found to differ substantially from the other peptide sequences, displaying 310-helical structure over the sequence RGVGPV (supplemental Fig. 16).

Further analysis also revealed that substitution of the Pro residue resulted in loss in binding for all amino acids (supplemental Table 2). If the proposed hydrogen bond was indeed functionally important, then this would suggest that the Ramachandran angles of the Pro78 residue were crucial in sustaining such a geometry. Because these mutations did not correspond to any biologically relevant systems, rationalization of this particular phenomenon will be the basis of future work.

DISCUSSION

The monoclonal antibody 8G5 was found to be able to discriminate between peptides representative of the β3 loops of hCGβ and LHβ (namely hCGβ66–80 and LHβ86–100, respectively), which differ by only a single amino acid. Such a strong change in affinity resulting from a point mutation, with such a small change in chemical structure, aminocarbonyl group (Asn) for a carboxyl group (Asp), was remarkable. We therefore sought to determine whether there were structural differences between these two peptides because such variations might give insights into explaining the substantially weaker binding of the LH version of the epitope with the paratope.

Over the residues Pro-Arg-Gly-Val, the type of β-turn varied; type I and II β-turn were observed in hCGβ66–80 and LHβ86–100, respectively. Compared with the results obtained experimentally, the secondary structures are consistent with an ensemble of open structures and turn motifs.

The simulations of these peptides also revealed the presence of a proposed hydrogen bond clasp, present in hCGβ66–80. Because this feature is present in the crystallographic structure of the hCGβ subunit, it would suggest that such a feature is important in the stabilization of a particular turn type and thus, the molecular recognition mechanism that endows mAb 8G5 with a strong binding preference for hCGβ. In the case of LHβ86–100, neither carboxylate oxygen was found to present a peak below the assumed 2.5-Å threshold, which therefore appeared to support the hypothesis that the stabilizing hydrogen bond was not favored in the presence of the deprotonated Asp97 residue. The lack of a hydrogen bond clasp, coupled with the difference in turn type spanning the residues Pro-Arg-Gly-Val, suggests that these structural features are important in the differential molecular recognition mechanism of the mAb 8G5 between the different β subunits of hCG and LH.

The presence of the hydrogen bond and type I β-turn in SIRLPGCPRGVHPVV, would appear to support the notion that the ability of 8G5 to discriminate between the β subunits of hCG and LH was due to a well defined structural difference between the two peptides. Furthermore, molecular dynamics simulations of SIRLPGCPRGVLPVV and SIRLPGCPRGVGPVV revealed stark contrasts in the predicted secondary structures. Because both peptide sequences showed diminished affinity for 8G5, the models suggest that any deviation from the structure shared by hCGβ66–80 and the histidine mutant would result in significant loss in binding.

Supplementary Material

This work was supported by the Strategic Research Programme of the National Physical Laboratory and the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Tables 1 and 2 and Figs. 1–16.

- hCG

- human chorionic gonadotropin

- Fmoc

- N-(9-fluorenyl)methoxycarbonyl

- FSH

- follicle-stimulating hormone

- HFIP

- hexafluoroisopropanol

- LH

- luteinizing hormone

- TSH

- thyroid-stimulating hormone.

REFERENCES

- 1. Lapthorn A. J., Harris D. C., Littlejohn A., Lustbader J. W., Canfield R. E., Machin K. J., Morgan F. J., Isaacs N. W. (1994) Nature 369, 455–461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cole L. A. (2007) Placenta 28, 977–986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. O'Connor J. F., Birken S., Lustbader J. W., Krichevsky A., Chen Y., Canfield R. E. (1994) Endocr. Rev. 15, 650–683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sturgeon C. M., McAllister E. J. (1998) Ann. Clin. Biochem. 35, 460–491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gronowski A. M., Grenache D. G. (2009) Clin. Chem. 55, 1447–1449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Stenman U. H. (2001) Clin. Chem. 47, 815–820 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ozturk M., Bellet D., Manil L., Hennen G., Frydman R., Wands J. R. (1987) Endocrinology 120, 549–558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ozturk M., Berkowitz R., Goldstein D., Bellet D., Wands J. R. (1988) Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 158, 193–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Pierce J. G. (1971) Endocrinology 89, 1331–1344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pierce J. G., Parsons T. F. (1981) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 50, 465–495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lund T., Delves P. J. (1998) Rev. Reprod. 3, 71–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wu H., Lustbader J. W., Liu Y., Canfield R. E., Hendrickson W. A. (1994) Structure 2, 545–558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Berger P., Sturgeon C., Bidart J. M., Paus E., Gerth R., Niang M., Bristow A., Birken S., Stenman U. H. (2002) Tumor Biol. 23, 1–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Elliott M. M., Kardana A., Lustbader J. W., Cole L. A. (1997) Endocrine 7, 15–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Birken S., Armstrong E. G., Kolks M. A. G., Cole L. A., Agosto G. M., Krichevsky A., Vaitukaitis J. L., Canfield R. E. (1988) Endocrinology 123, 572–583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sturgeon C. M., Berger P., Bidart J. M., Birken S., Burns C., Norman R. J., Stenmanm U. H. (2009) Clin. Chem. 55, 1484–1491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mitchell H., Seckl M. J. (2007) Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 260–262, 310–313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Meloen R. H., Puijk W. C., Schaaper W. M. M. (1997) in Immunology Methods Manual (Lefkovits I. ed) pp. 982–988, Academic Press, San Diego [Google Scholar]

- 19. Slootstra J., Puijk W. C., Ligtvoet G., Langeveld J., Meloen R. H. (1996) Mol. Divers. 1, 87–96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kuipers B. J. H., Gruppen H. (2007) J. Agric. Food Chem. 55, 5445–5451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Valenti L. E., Paci M. B., De Pauli C. P., Giacomelli C. E. (2011) Anal. Biochem. 410, 118–123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. MacKerell A., Bashford D., Bellott M., Dunbrack R., Evanseck J., Field M., Fischer S., Gao J., Guo H., Ha S., Joseph-McCarthy D., Kuchnir L., Kuczera K., Lau F., Mattos C., Michnick S., Ngo T., Nguyen D., Prodhom B., Reiher W., Roux B., Schlenkrich M., Smith J., Stote R., Straub J., Watanabe M., Wiorkiewicz-Kuczera J., Yin D., Karplus M. (1998) J. Phys. Chem. B 102, 3586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tuckerman M. E., Yarne D. A., Samuelson S. O., Hughes A. L., Martyna G. J. (2000) Comput. Phys. Commun. 128, 333–376 [Google Scholar]

- 24. Samuelson S. O., Tobias D. J., Martyna G. J. (1997) J. Phys. Chem. B 101, 7592–7603 [Google Scholar]

- 25. Heinig M., Frishman D. (2004) Nucleic Acids Res. 32, W500–W502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Byler D. M., Susi H. (1986) Biopolymers 25, 469–487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bandekar J., Krimm S. (1979) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 76, 774–777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Perczel A., Fasman G. D. (1992) Protein Sci. 1, 378–395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.