Abstract

We explored cross-sectionally the roles in bipolar spectrum symptomatology of two broad motivational systems that are thought to control levels of responsiveness to cues of threat and reward, the Behavioral Inhibition System (BIS) and the Behavioral Activation System (BAS). Undergraduate students (n = 357) completed questionnaires regarding (a) bipolar spectrum disorders [the General Behavior Inventory (GBI), a well-established clinical screening measure], (b) current depression and mania symptoms (the Internal State Scale; ISS), and (c) BIS/BAS sensitivities (the BIS/BAS scales). Validated cutoff scores on the GBI were used to identify individuals at risk for a mood disorder. It was hypothesized that, among at-risk respondents, high BAS and low BIS levels would be associated with high current mania ratings, whereas low BAS and high BIS would be associated with high current depression ratings. Multiple regression analyses indicated that, among at-risk individuals (n = 63), BAS accounted for 27% of current mania symptoms but BIS did not contribute. For these individuals, BAS and BIS were both significant and together accounted for 44% of current depressive symptoms.

Keywords: bipolar disorder, behavioral activation, behavioral inhibition, BIS/BAS scales

INTRODUCTION

With its intense fluctuations from suicidal depressions to manic excitement, bipolar disorder has been described as a “magnification of common human experience” (Goodwin & Jamison, 1990, p. 3). The profound impairment associated with bipolar disorder is well known (Coryell, Scheftner, Keller, & Endicott, 1993; Gelenberg & Hopkins, 1988; Goldberg, Harrow, & Grossman, 1995; Weissman, Leaf, Tischler, & Blazer, 1988) and underlined dramatically by the alarming finding that as many as 19%of affected individuals will die from suicide (Isometsa, 1993). Evidence strongly supports the biological nature of this disorder (Gershon, Berrettini, Nurnberger, & Goldin, 1989; Science, 1992), and psychotropic medication is agreed to be generally effective in the treatment of manic depressive illness (Ahrens, Grof, Moller, & Muller-Oerlinghausen, 1995; Gelenberg & Hopkins, 1993; Silverstone & Romans-Clarkson, 1989).

Despite the biological foundation of this condition, psychosocial factors such as stress and social support exert a critical influence in the etiology and symptomatology of bipolar disorder (Miklowitz, Goldstein, Nuechterlein, & Snyder, 1988; O’Connell, 1986). Current research suggests, then, that a biological diathesis view may provide an appropriate conceptual frame—some individuals are biologically predisposed to experience mania or depression, but particular environmental contingencies control when symptoms surface among these at-risk individuals(Johnson & Roberts, 1995).

Neurobehavioral Systems Underlying Appetitive and Aversive Motivation

In disentangling which components predispose individuals to develop bipolar disorder, theorists have recently focused on broad neurobehavioral systems that are thought to underlie appetitive and aversive motivation among humans and other mammals (Johnson & Roberts, 1995; Depue & Iacono, 1989; Gray, 1989, 1990, 1991). These systems may control the intensity with which individuals respond behaviorally and affectively to different classes of stimuli. Whereas the Behavioral Activation System (BAS) governs elation and goal-seeking behavior in response to cues of reward, the Behavioral Inhibition System (BIS) governs anxiety and the interruption of behavior in response to cues of threat (Gray, 1989, 1990, 1991). BAS is said to control positive affect, and BIS may control negative affect (e.g., Clark, Watson, & Mineka, 1994). Individuals differ in their degree of responsiveness of the BAS and the BIS (Carver & White, 1994), and constellations of extreme responsiveness in these systems may place individuals at risk for bipolar disorder (Depue & Iacono, 1989; Depue, Krauss, & Spoont, 1987; Depue & Zald, 1993) and a host of other psychopathological syndromes, including childhood externalizing disorders (Milich, Hartung, Martin, & Haigler, 1994), substance abuse (Wise & Rompre, 1989), and psychopathy (Newman, Patterson, & Kosson, 1987).

In response to cues of conditioned reward, the BAS has been found to control goal-seeking behavior and positive affect such as happiness, hope, or elation (Carver & White, 1994; Gray, 1991). Neural components of the BAS are the dopaminergic fibers that ascend from the substantia nigra and nucleus A10 in the ventral tegmental area to innervate parts of the frontal cortex, the basal ganglia, and the limbic system (Gray, 1991). The BIS, in contrast, is sensitive to cues of threat: specifically, to conditioned punishment, nonreward, novelty, and innate fear stimuli. In response to such threats, the BIS is said to trigger increments in behavioral inhibition, anxiety, arousal, and threat-directed attention (e.g., Gray, 1991). Low BIS sensitivity has been theoretically and empirically related to indifference to threats, disinhibited behavior, and an incapacity to become anxious (e.g., Gray, 1991; Milich et al., 1994). Neural components of the BIS include the septal and the hippocampal formations in the brain (Gray, 1991). According to Gray (1994), BIS-related responsiveness to threats is mediated by noradrenergic activity originating in the locus coeruleus and by serotonergic activity originating in the median raphe. In short, whereas the BAS controls sensitivity and responsiveness to rewards via dopaminergic activity in the mesolimbic system, the BIS controls sensitivity and responsiveness to threats via noradrenergic and serotonergic activity in the septohippocampal system (cf. Gray, 1994).

The link between the BIS and BAS and bipolar disorder appears plausible when considering the overlapping manifestations of these systems, on the one hand, and mania and depression symptoms, on the other (e.g., increased goal-seeking behavior during mania and BAS activation or fearlessness during mania and BIS inactivity). Recent neurochemical research further suggests the plausibility of this link. Specifically, this research shows that mania and depression symptoms may be related to patterns of over and underactivity in the dopamine, norepinephrine, and serotonin systems—the same neurotransmitters that underlie the BIS and the BAS. Diehl and Gershon (1992), for example, concluded in their review that dopamine overactivity may be related to mania symptoms, whereas dopamine underactivity may be related to retarded depression, a particularly common type of bipolar depression (Depue & Iacono, 1989). Serotonin depletion, in contrast, has been linked with the disinhibition of a variety of behaviors (cf. Goodwin & Jamison, 1990). In short, a variety of drug and animal studies (for reviews, see Goodwin & Jamison, 1990; Diehl & Gershon, 1992) indicates that dopamine overactivity and serotonin underactivity may be associated with manic disinhibition, whereas dopamine underactivity may be associated with retarded depression. These findings are consistent with Gray’s theory (1994), according to which mania may result from excessive dopamine-mediated responsiveness to rewards (i.e., high BAS) along with defective serotonin- and norepinephine-mediated responsiveness to threats (i.e., low BIS).

Although Gray (1971) first proposed his neurobehavioral theory more than two decades ago, measurement of the psychological dimensions of the BIS and the BAS has been difficult and ambiguous (cf. Carver & White, 1994). Scales that have previously been used to estimate BIS and BAS sensitivities generally deviate substantially from the content of Gray’s theory. BAS measures, for example, have typically assessed extraversion and impulsiveness rather than reward responsiveness, and BIS measures have failed to differentiate manifest anxiety from anxiety-susceptibility (Carver & White, 1994). Carver and White (1994) developed a brief self-report questionnaire, the BIS/BAS scales, to measure Gray’s dimensions more directly. The BIS scale predicted nervousness immediately following exposure to undesirable stimuli, whereas the BAS scale predicted happiness immediately following exposure to desirable stimuli. Recent studies have also related the BIS/BAS scales to asymmetrical levels of frontal cortical activation (Harmon-Jones & Allen, 1997; Sutton & Davidson, 1997), which in turn has been linked to depression (Allen, Iacono, Depue, & Arbisi; 1993; Henriques & Davidson, 1991). To date, the BIS/BAS scales have not been used to examine vulnerabilities to bipolar disorder.

Hypotheses

The goal of this study was to explore further the roles of self-reported threat and reward sensitivities (i.e., BIS/BAS levels) in the bipolar mood disorder spectrum. We classified participants into normal vs. vulnerable to a mood disorder with a well-validated questionnaire, the General Behavior Inventory (GBI; Depue, Krauss, Spoont, & Arbisi, 1989). Consistent with Gray’s theory (1991), we hypothesized that among individuals at risk for a mood disorder, low BAS levels would be associated with current depression ratings, whereas low BIS and high BAS levels would be associated with current mania ratings. We also explored whether high BIS levels—over and above low BAS levels—might be related to depression. Although Gray (e.g., 1994) postulated that high BIS activity likely corresponds primarily to anxiety, he also claimed that “neurotic depression” may stem from heightened activity in the BIS. This BIS-mediated primary responsiveness to cues of threat may “give rise secondarily to inhibition of the BAS, experienced as depression mixed with anxiety” (Gray, 1994, p. 47). Clark, et al. (1994) also view BIS as broadly relevant to negative affect, which they consider a core component of depression. Given this analysis, it seems plausible to examine whether self-reports of heightened threat sensitivity are related to symptoms of depression.

METHOD

Participants and Procedure

Three-hundred fifty-seven undergraduate students enrolled in introductory psychology courses at the University of Miami participated (208 women, 146 men, 3 who did not indicate gender). The majority of participants were freshmen or sophomores (307) between 17 and 20 years of age. (314). Students participated in partial fulfillment of a course requirement. After reading and signing an informed consent form, participants completed the questionnaires and were then offered a verbal explanation of the goals of the research.

Measures

The General Behavior Inventory (GBI)

The GBI (Depue et al., 1989) is a 73-item self-report measure designed to identify individuals who have experienced symptoms of depression, hypomania, or cyclothymia. The GBI is a measure of lifetime diagnosis of affective disorders; it does not assess whether respondents are currently suffering from a mood syndrome. The GBI consists of three subscales: depression, hypomania, and biphasic. The hypomania and biphasic scores, however, are commonly added to construct a mania index (Depue et al., 1989). Responses are coded on 4-point Likert-type scales, ranging from “never or hardly ever” to “very often or almost constantly” Depue and his colleagues (1989) recommended that responses of 3 or 4 on an item be counted as 1, whereas responses of 1or 2 be counted as 0. For case identification, the cutoff scores on both the depression and the mania indices recommended by Depue et al. (1989) were used. Respondents with a summed score of 22 or above on the depression index but below 11 on the mania index were classified as at risk for depression. Those who scored at 12 or above on the depression index and at 11 or above on the mania index were classified as cyclothymia/bipolar-prone, and those who scored below 12 on the depression index and at 13 or above on the mania index were classified hypomania/mania-prone. All others were classified as non-mood-disturbed or normal. These cutoff scores were proposed for nonclinical university populations by Depue (1989), based on a sample of 1068 university students.

Adequate reliability and validity of the GBI have been demonstrated by Depue and his colleagues (e.g., Depue, 1989). Internal consistencies for the GBI have ranged from .90 to .96. Test-retest reliabilities over 12 to 16 weeks have ranged from .71to .74. Using a modified Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia—Lifetime Version (SADS-L) as a diagnostic criterion, the sensitivity of the GBI for nonclinical university populations has also been found to be adequate [.76 to .78 (Depue et al., 1989)]. Most importantly for this study, the GBI’s specificity has been reported to be superior, resulting in a low rate of false positives [.99 (Depue et al., 1989)]. The GBI has also demonstrated predictive validity; for example, individuals identified as mood-disturbed by the GBI exhibited high levels of psychological impairment (e.g., suicidal ideation, receiving psychiatric treatment) at a 19-month follow-up (Klein & Depue, 1984).

The Internal State Scale (ISS)

The ISS (Bauer et al., 1991) is a 17-item self-report measure of current mania and depression symptoms. Bauer and co-workers’ (1991) principal-components factor analysis yielded four subscales, two of which correlated highly with well-established clinical rating scales for mania and depression and were thus used to measure these constructs in the current study. Specifically, the activation scale correlated significantly (r = .60, p < .05) with the Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS; Young, Biggs, & Meyer, 1978), and the depression index correlated significantly (r = .84, p < .05) with the Hamilton (1960) Depression Rating Scale (HDRS). Internal consistencies for all ISS scales were reported to be adequate (Bauer et al., 1991), with coefficient α ranging from .81 to .92.

Although a 100-mm visual-analog line was recommended for scoring by Bauer et al. (1991), a Likert-type scale with response options from 1 (not at all today) to 5 (extremely today) was used in this research. This minimal change appears justified considering that Bauer et al. (1991, p. 808) chose the visual-analog format because they anticipated respondents to have “somewhat impaired attention due to their affective syndrome”. Clearly, the college student sample used in this research could be expected to exhibit adequate attention capacities. Given further (a) that the end points of Bauer et al.’s (1991) visual-analog scale were identical with those of our 5-point scale and (b) that respondents in both formats are presented with gradated options between those end points, we assumed that the increased feasibility associated with this change would outweigh possible psychometric costs.

The BIS/BAS Scales

This 20-item self-report measure assesses trait sensitivity levels of the Behavioral Activation System and the Behavioral Inhibition System. Likert-type response scales that range from 1 (very false for me) to 4 (very true for me) were used. The BIS scale consists of seven items, two of which are reversed for scoring. Based on the results of their factor analysis, Carver and White (1994) divided the BAS scale into three separate subscales: (1) BAS reward responsiveness (five items), (2) BAS drive (four items), and (3) BAS fun seeking (four items). Alpha internal consistencies of these subscales have ranged from .66 (fun seeking) to .76 (drive); test-retest correlations over 8 weeks have ranged from .59(reward responsiveness) to .69 [fun seeking; see Carver & White (1994) for the full set of items along with evidence bearing on the adequate convergent, discriminant, and predictive validity of these scales].

RESULTS

Internal consistencies, means, and standard deviations of the scales are presented in Table I. The intercorrelations among the BIS/BAS subscales as well as the ISS subscales and the GBI subscales were consistent with previous research (Bauer et al., 1991; Carver & White, 1994; Depue et al., 1989).

Table I.

Internal Consistencies, Means, and Standard Deviations of Scales (n = 357)

| Scale | α | M | SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| BIS | .75 (.75) | 20.57 (20.59) | 3.95 (4.58) |

| BAS reward responsiveness | .69 (.73) | 17.45 (16.74) | 2.36 (3.17) |

| BAS fun seeking | .71 (.73) | 12.15 (12.16) | 2.45 (2.85) |

| BAS drive | .84 (.85) | 11.52(11.19) | 2.70(3.21) |

| GBI depression | .96 (.91) | 83.60(116.58) | 22.83 (20.23) |

| GBI mania | .90 (.79) | 53.75 (70.52) | 11.90(10.34) |

| ISS activation | .73 (.65) | 10.40 (13.26) | 3.82 (4.12) |

| ISS depression | .77 (.75) | 3.56 (4.97) | 1.92 (2.44) |

Note. Statistics for the subgroup of 63 participants classified as at risk for a mood disorder are in parentheses. GBI scales were scored on 4-point Likert-type scales.

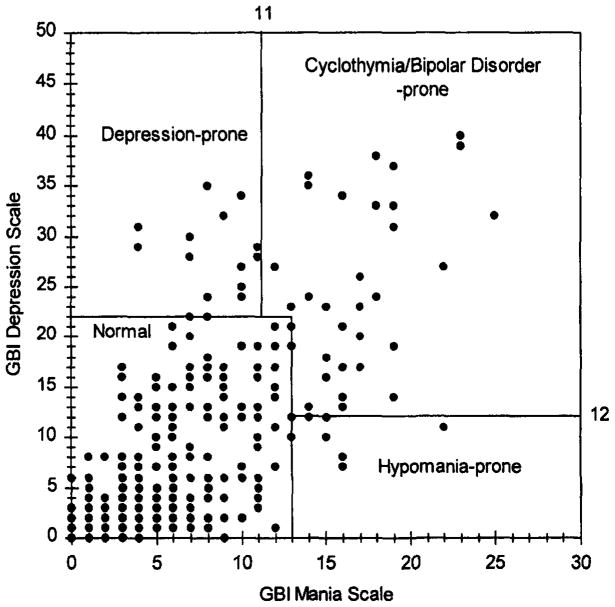

Figure 1 illustrates the distribution of scores on the GBI subscales. Using Depue’s (1989) cutoff scores for case identification, 294of 357 respondents with complete GBI scores were classified as normal, 13 as depression-prone, 6 as hypomania-prone, and 44 as cyclothymia-prone. The latter three groups were combined to form a pool of 63 participants classified as at risk for a mood disorder. These individuals constituted the focus of the primary analyses.

Fig. 1.

Classifications of respondents into normal and mood disorder-prone groups.

Bivariate correlations between the BIS/BAS scales and symptoms of depression and hypomania were examined next (see Table II). Among students classified as at-risk, positive correlations were observed between each of the BAS scales and ISS activation (current mania). As expected, all three BAS scales also correlated inversely with ISS depression among at-risk students. In this group, BIS was positively associated with depression but unrelated to hypomania symptoms. Among students classified as not at risk, in contrast, correlations between the BIS/BAS scales and current symptoms were weak (see Table II). Only two of three BAS scales were linked with ISS activation, and BIS was linked with depression. These correlations were less than half in magnitude among students classified as normal, compared to those at risk for a mood disorder. Because zero-order correlations do not permit inferences about unique associations of the BIS/ BAS scales with current symptomatology, we conducted a set of regression analyses.

Table II.

Zero-Order Correlations Between the BIS/BAS Scales and ISS Depression and Hypomania

| ISS symptom scale | BIS | BAS total score | BAS fun seeking | BAS drive | BAS reward responsiveness |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participants at risk for bipolar spectrum symptomatology (n = 63) | |||||

| Activation (Hypomania) | −.01 | .48** | .49** | .33** | .38** |

| Depression | .32** | −.53** | −.39** | −.49** | −.44** |

| Participants not at risk for bipolar spectrum symptomatology (n =294) | |||||

| Activation (Hypomania) | −.11 | .20** | .20** | .16** | .10 |

| Depression | .14* | −.05 | −.01 | −.01 | −.11 |

p< .05.

p < .01.

Two hierarchical multiple regression analyses were performed: one with the ISS depression scale as a dependent variable and one with the ISS activation scale (current mania) as a dependent variable (see Table III). After entering the three BAS scales as a set in a first block, the BIS scale was entered as a second block to determine the amount of variance in current depression and mania BIS could incrementally account for, over and above the contribution of BAS. One advantage hierarchical regression holds over other types of regressions (e.g., stepwise regression) is that the order of entry is theoretically determined in advance, so that conceptually meaningful increments in variance accounted can be obtained (cf. Cohen & Cohen, 1983). Given that BIS and BAS are theoretically separate systems, it seemed important to enter the respective scales in separate steps. Consistent with Cohen and Cohen’s (1983) recommendations, we entered first those independent variables with the more compelling theoretical ties to the dependent variable—in this case, the BAS scales. Because the link of BIS to depression and mania appears more exploratory, this scale was entered in the second and last step.

Table III.

Hierarchical Regressions: BIS/BAS Prediction of Current Symptoms of Mania and Depression Among Participants at Risk for a Mood Disorder (n = 63)

| R2 change | F change | df change | Final β | t | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable: current manic symtpoms | ||||||

| Block 1 (BAS set) | .27 | 7.28 | 3,59 | <.001 | ||

| BAS reward responsiveness | .23 | 1.4 | .17 | |||

| BAS drive | −.05 | -.31 | .76 | |||

| BAS fun seeking | .41 | 2.88 | .01 | |||

| Block 2 | .003 | .22 | 1, 58 | .95 | ||

| BIS | −.06 | -.47 | .64 | |||

| Dependent variable: Current depressive symptoms | ||||||

| Block 1 (BAS set) | .28 | 7.74 | 3,59 | <.001 | ||

| BAS reward responsiveness | −.53 | −3.63 | .00 | |||

| BAS drive | −.06 | −.42 | .68 | |||

| BAS fun seeking | −.06 | −.50 | .62 | |||

| Block 2 | .16 | 16.50 | 1, 58 | <.001 | ||

| BIS | .48 | 4.1 | <.001 | |||

Note. P values of individual predictors refer to the final regression model, after entering all variables into the equation.

Consistent with our hypotheses, the prediction of concurrent manic activation by BAS was significant (see Table III), with the fun seeking subscale carrying virtually the entire weight in this prediction. The direction of the BAS prediction of mania was consistent with the hypotheses, with higher levels of fun seeking being related to higher levels of manic activation. Interestingly, although the association of BAS fun seeking with ISS manic activation was highly significant (β = .41, p < .01), neither of the other two BAS subscales was related significantly to mania symptoms. It was further expected that low BIS levels would contribute to the prediction of concurrent manic activation, even after controlling for the influence of BAS. This hypothesis, however, received no support. In summary, BAS levels accounted for 27% of the variation in concurrent manic activation, but BIS levels were unrelated to mania scores.

The prediction of concurrent depression via BIS/BAS sensitivities in this sample was consistent with hypotheses—both BAS and BIS levels predicted ISS depression scores in the expected directions.3 Reward sensitivities (BAS) accounted for 28% of the variance in depression scores, and threat sensitivities raised this prediction by 16% to 44%. After entering all subscales, the BIS and the BAS reward-responsiveness subscales were the most potent predictors of concurrent depression. The more responsive subjects reported being to threats, and the less responsive to rewards, the higher their concurrently assessed depression scores were.

It might be argued that respondents classified as at risk for depression only (with low scores on the GBI mania index) should not be included here. Many individuals at risk for depression may differ fundamentally from those vulnerable to cyclothymia or bipolar disorder. For this reason, we also conducted separate analyses without this subgroup. Results for the 50 remaining respondents were generally equivalent to those shown in Table II. BAS fun seeking was the only significant predictor of current mania (final β = .33, t = 2.21, p = .03); both BIS and BAS reward responsiveness predicted current depression (for BIS, final β = .68, t = 5.03, p < .001; for BAS reward responsiveness, final β = −.49, t = −3.20, p = .002). Among this subgroup, BIS and BAS together accounted for a total 18% of the variance in current mania and 44% of the variance in current depression.

To compare whether the sizes of the effects obtained were indeed greater among those at-risk for a mood disorder in comparison to those classified as normal, two additional regression analyses were conducted, including only the 294 subjects classified as normal by the GBI. Results paralleled the first analyses in that BAS (especially fun seeking) but not BIS predicted concurrent mania symptoms, whereas both BAS (especially reward responsiveness) and BIS predicted concurrent depression. Consistent with the theoretical model, effect sizes of these predictions were much smaller among normal participants: the total R2 for the BIS/BAS prediction of mania was only .06 [F(4,287) = 4.30, p = .002], and the total R2 for the BIS/BAS prediction of depression was only .05 [F(4,287) = 3.86, p = .005]. This reduction in effect size among normal participants may be partly explained by the slight reduction of range in both the independent and the dependent variables. As shown in Table IV, however, this range reduction appeared negligible. Moreover, one would expect individuals at risk for mood disorders to exhibit a wider range of current affect than normals; thus, a wider range in their ISS scores may be realistic rather than artifactual.

Table IV.

Ranges, Means, and Standard Deviations Among At-risk [n = 63; vs. Normal (n = 294)] Participants

| ISS Mania | ISS Depression | BAS-FS | BAS-D | BAS-R | BIS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 13.27 (9.28) | 4.97 (3.26) | 12.16 (12.15) | 11.19(11.59) | 16.71 (17.61) | 20.59 (20.58) |

| SD | 4.12 (3.46) | 2.44 (1.64) | 2.85 (2.37) | 3.21 (2.58) | 3.17 (2.12) | 4.58 (3.79) |

| Min | 5(5) | 2(2) | 4(6) | 4(4) | 5(8) | 10(7) |

| Max | 25(23) | 10 (10) | 16 (16) | 16 (16) | 20 (20) | 28 (28) |

Note. ISS Mania, ISS Activation scale; ISS Depression, ISS Depression Index; BAS-FS, BAS Fun Seeking scale; BAS-D, BAS Drive scale; BAS-R, BAS Reward Responsiveness Scale.

We focused in this project on associations between the BIS/BAS scales and current symptoms among individuals at-risk for a mood syndrome. It is also reasonable to ask, however, whether the BIS/BAS scales are linked with lifetime vulnerability to mania and depression, controlling for current symptom intensity.4 Because the GBI is a measure of lifetime risk and the ISS one of current symptom intensity, our data permitted us to address this point. Partial correlation analyses were performed between the BIS/BAS scales and the GBI depression and hypomania/mania scales, controlling for ISS depression and mania (see Table V).

Table V.

Partial Correlations Between BIS/BAS Scales and Lifetime Vulnerability to Mania and Depression (GBI), Controlling for Current Intensity of Mania and Depression Symptoms (ISS)

| BIS/BAS scales | At-risk participants (n = 63) |

Not-at-risk participants (n = 294) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GBI Mania | GBI Depression | GBI Mania | GBI Depression | |

| BIS | −.03 | .03 | −.03 | .17** |

| BAS total score | .42** | −.06 | .11 | .03 |

| Fun seeking | .37** | .12 | .26** | .12* |

| Reward responsiveness | .29* | −.11 | −.07 | −.04 |

| Drive | .35** | −.15 | .06 | −.01 |

p < .05.

p < .01.

Among students classified as at-risk, all three BAS scales were linked with lifetime mania vulnerability, even when controlling for current mania intensity. When controlling for current depression, no links emerged between the BIS/BAS scales and lifetime depression vulnerability. In the at-risk group, partial correlations between BIS and lifetime vulnerability were not significant for either mania or depression. In the group of 294 students classified as not at-risk, BIS was associated with lifetime depression vulnerability. In this group, BAS fun seeking was also linked with both mania and depression vulnerability. The major finding of these partial correlations, in summary, concerned the link between BAS and heightened lifetime vulnerability to mania, especially among individuals at risk for a mood syndrome.

DISCUSSION

What are the underlying mechanisms that control fluctuations in mood and behavior among individuals afflicted with bipolar spectrum disorders? This cross-sectional exploration suggests that individual differences in dispositional sensitivities to different classes of stimuli, as measured by the BIS/BAS scales, may contribute significantly to the explanation of mania and depression. BAS sensitivities, or reactivity levels to rewarding events, are relatively potent predictors of concurrently assessed symptoms of mania and depression. Whereas one component of BAS (fun seeking) was related uniquely to manic activation, another component (reward responsiveness) was related uniquely to depression. It is equally important to note, however, that two of three BAS scales were not uniquely associated with either depression or mania symptoms in each of the two main regression analyses.

BIS sensitivities, or levels of responsiveness to threatening events, on the other hand, appeared to be related to symptoms of depression only. The more responsive participants were to undesirable events, the more intense symptoms of concurrent depression they also reported. Because of the possible absence of individuals with currently clinical levels of mania in this sample, however, the lack of association between the BIS and mania must be regarded as tentative. Another possible reason for the lack of association between BIS and manic activation may be found in the ostensibly different levels of actual exposure to threats between high-BIS and low-BIS subjects. That is, those who are highly sensitive to threats (high BIS) may avoid exposure to threatening events, whereas those indifferent to threats (low BIS) may be exposed to greater threat levels. Because BIS levels and threat exposure combined are thought to control affective responses, then those with a high BIS/low exposure combination may exhibit equivalent affective responses to those with a low BIS/high exposure combination. By measuring threat exposure as well as BIS levels among mania-prone individuals, follow-up studies could gain a more precise understanding of the role threat sensitivities play in the regulation of mood disorder symptoms. The measurement of such event exposure could also establish links to life events theories in bipolar disorder etiology. Sophisticated instruments for the measurement of life events have long been developed (e.g., Brown & Harris, 1986); investigators would benefit from integrating these into follow-up projects to this study.

Our findings are also consistent with studies that examined associations between affect and symptoms of bipolar disorder. Lovejoy and Steuerwald (1992), for example, found among 324 students that negative affect was linked with depression, whereas positive affect was linked with both hypomanic and depressive symptoms, as measured by the GBI. Because BIS is thought to control negative affect and BAS positive affect (e.g., Clark et al., 1994), Lovejoy and Steuerwald’s findings are entirely compatible with the results reported here.

Limitations and Future Work

This cross-sectional exploration lends some support to the notion that BIS/BAS sensitivities vary concurrently with symptomatic states among mood disturbed individuals. It does not, however, show that unique BIS/BAS constellations cause or precede symptom cycles. That is, it is possible that the BIS/BAS differences reported may be no more than reflections or consequences of symptom cycles, rather than antecedents thereof. We did find, however, that among at-risk individuals, BAS was linked with lifetime vulnerability to mania, even after controlling for current mania intensity. This finding suggests that high trait levels of BAS may constitute a risk factor separate from mood state fluctuations. Given this initial support, prospective studies to gain further information on this point would certainly seem warranted.

A further limitation of this study concerns the exclusive use of self-report questionnaires. As convenient as this strategy may be for the purposes of large-scale exploratory studies, it fails to control for common-method biases. Self-reports may also correlate simply because of item overlap, which renders findings difficult to interpret (cf. Nicholls, Licht, & Pearl, 1982). Future studies in this area would benefit, then, from measuring constructs on different empirical levels. The BIS and the BAS, for example, could be measured physiologically, and bipolar spectrum symptomatology could be identified based on clinician-administered interviews. Alternatively, behavioral tasks that have been used in BIS/BAS investigations of disruptive childhood disorders (cf. Milich et al., 1994) could be adopted for research with bipolar disordered participants.

This study focused on Gray’s BIS/BAS model (e.g., 1989,1990,1991) to test whether dispositional sensitivities could predict concurrently assessed symptoms of mania and depression. Other theorists, however, including Cloninger (e.g., Cloninger, 1986; Stallings, Hewitt, Cloninger, Heath, & Eaves, 1996), Depue (Depue & Iacono, 1989; Depue & Zald, 1993), and Eysenck (e.g., 1967) have also developed sophisticated theories of biologically based personality dimensions. These theories parallel those of Gray in critical aspects but differ in others. Follow-up investigations ought to compare and integrate these systems to arrive at parsimonious explanations of the role of neurobehavioral systems in bipolar symptomatology. Cloninger’s system (e.g., Stallings et al., 1996) may be particularly relevant for such endeavors because his dimensions of novelty seeking and harm avoidance are said to reflect directly the functions of Gray’s BAS and BIS, respectively.

A final important theoretical point pertains to the pathways by which BIS/BAS sensitivities could influence affect and symptoms over time. For example, BIS/BAS sensitivities may determine not only the strength of a person’s emotional reaction to threat or reward, but also the level of exposure to cues of threat and reward (cf. Fowles, 1987). A sophisticated framework for testing whether personality constructs influence event exposure, reactivity, or both, has been formulated by Bolger and Zuckerman (1995). In their study, Bolger and Zuckerman (1995) showed that the effects of neuroticism on daily distress could best be explained by a reactivity rather than an exposure paradigm. In other words, although exposure explained some of the effects of neuroticism on distress, neuroticism-related differences in reactivity to stressful events were even more potent predictors of daily distress. Bolger and Zuckerman’s (1995) framework could well be applied to investigate whether BIS/BAS sensitivities determine exposure or reactivity levels to rewards and threats, or both.

In summary, the present study provides evidence that dispositional sensitivity levels to cues of threat and reward (as measured by the BIS/BAS scales) are associated more strongly with mania and depression symptoms among individuals at-risk for a mood disorder, compared to undergraduate students classified as normal. Among those vulnerable to major depressive disorder or bipolar disorder, low reward and high threat sensitivities may precede (or reflect) depressive episodes, and high reward sensitivities may precede (or reflect) manic episodes. Prospective follow-up studies with clinical populations are called for to examine further the intriguing implications of BIS/BAS theories in the bipolar spectrum of the mood disorders.

Acknowledgments

This project was completed as part of the first author’s master’s thesis at the University of Miami. Thanks are due to R. Jay Turner, who provided comments on an earlier version of this article.

Footnotes

There is some conceptual ambiguity about the source of depressed affect. Gray (e.g., 1994) links this affective quality to BIS activity, whereas Carver and colleagues (e.g., Carver, Lawrence, & Scheier, 1996; Carver & Scheier, 1998) link it to BAS function. Since there is a high comorbidity between depression and anxiety, it is difficult to sort this issue out empirically. Because anxiety was not measured in this data set, the present results do not permit a test of these competing hypotheses.

We thank Don Fowles for this suggestion.

References

- Ahrens B, Grof P, Moller HJ, Muller-Oerlinghausen B. Extended survival of patients on long-term lithium treatment. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 1995;40:241–246. doi: 10.1177/070674379504000504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen JJ, Iacono WG, Depue RA, Arbisi P. Regional electroencephalographic asymmetries in bipolar seasonal affective disorder before and after exposure to bright light. Biological Psychiatry. 1993;33:642–646. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(93)90104-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer MS, Crits-Christoph P, Ball WA, Dewees E, McAllister T, Alahi P, Cacciola J, Whybrow PC. Independent assessment of manic and depressive symptoms by self-rating: Scale characteristics and implications for the study of mania. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1991;48:807–812. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810330031005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger N, Zuckerman A. A framework for studying personality in the stress process. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology. 1995;69:890–902. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.69.5.890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown G, Harris TO. Establishing causal links: The Bedford College studies of depression. In: Katschnig H, editor. Life events and psychiatric disorders: Controversial issues. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press; 1986. pp. 107–187. [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS, Scheier MF. On the self-regulation of behavior. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS, White TL. Behavioral inhibition, behavioral activation, and affective responses to impending reward and punishment: The BIS/BAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1994;67:319–333. [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS, Lawrence JW, Scheier MF. A control-process perspective on the origins of affect. In: Martin LL, Tesser A, editors. Striving and feeling: Interactions among goals, affect, and self-regulation. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 1996. pp. 11–52. [Google Scholar]

- Clark LA, Watson D, Mineka S. Temperament, personality, and the mood and anxiety disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1994;103:103–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloninger CR. A unified biosocial theory of personality and its role in the development of anxiety states. Psychiatric Developments. 1986;3:167–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Cohen P. Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Coryell W, Scheftner W, Keller M, Endicott J. The enduring psychosocial consequences of mania and depression. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1993;150:720–727. doi: 10.1176/ajp.150.5.720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Depue RA, Iacono WG. Neurobehavioral aspects of affective disorders. Annual Review of Psychology. 1989;40:457–492. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ps.40.020189.002325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Depue RA, Zald DH. Biological and environmental processes in nonpsychotic psychopathology: A neurobehavioral perspective. In: Costello CG, editor. Basic Issues in Psychopathology. New York: Guilford Press; 1993. pp. 127–237. [Google Scholar]

- Depue RA, Krauss SP, Spoont MR. A two-dimensional threshold model of seasonal bipolar affective disorder. In: Magnusson D, Oehman A, editors. Psychopathology: An interactional perspective. Personality, psychopathology, and psychotherapy. Orlando, FL: Academic Press; 1987. pp. 95–123. [Google Scholar]

- Depue RA, Krauss S, Spoont MR, Arbisi D. General Behavior Inventory identification of unipolar and bipolar conditions in a non-clinical university population. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1989;98:117–126. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.98.2.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diehl DJ, Gershon S. The role of dopamine in mood disorders. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 1992;33:115–120. doi: 10.1016/0010-440x(92)90007-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eysenck HJ. The biological basis of personality. Springfield, IL: Charles C Thomas; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Fowles DC. Application of a behavioral theory of motivation to the concepts of anxiety and impulsivity. Journal of Research in Personality. 1987;21:417–435. [Google Scholar]

- Gelenberg AJ, Hopkins HS. Report on efficacy of treatments for bipolar disorder. Psychopharmacology Bulletin. 1993;29:447–456. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gershon ES, Berrettini WH, Nurnberger JI, Jr, Goldin L. Genetic studies of affective illness. In: Mann JJ, editor. Models of depressive disorders: Psychological, biological, and genetic perspectives. The depressive illness series. New York: Plenum Press; 1989. pp. 109–142. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg JF, Harrow M, Grossman LS. Course and outcome in bipolar affective disorder: A longitudinal follow-up study. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1995;152:379–384. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.3.379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin FK, Jamison KR. Manic-depressive illness. New York: Oxford University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Gray JA. The psychology of fear and stress. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson; New York: McGraw Hill; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Gray JA. Fundamental systems of emotion in the mammalian brain. In: Perlarmo DS, editor. Coping with Uncertainty: Biological, Behavioral, and Developmental Perspectives. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1989. pp. 173–195. [Google Scholar]

- Gray JA. Brain systems that mediate both emotion and cognition. Cognition and Emotion. 1990;4:269–288. [Google Scholar]

- Gray JA. Neural systems, emotion, and personality. In: Madden J IV, editor. Neurobiology of learning, emotion, and affect. New York: Hillsdale Press; 1991. pp. 273–306. [Google Scholar]

- Gray JA. Framework for a taxonomy of psychiatric disorder. In: Van Goozen HM, Van De Poll NE, Sergeant JA, editors. Emotions: Essays on emotion theory. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1994. pp. 29–59. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harmon-Jones E, Allen JJB. Behavioral activation sensitivity and resting frontal EEG asymmetry: Covariation of putative indicators related to risk for mood disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1997;106:159–163. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.106.1.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henriques JB, Davidson RJ. Left frontal hypoactivation in depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1991;100:535–545. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.100.4.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isometsa ET. Course, outcome, and suicide risk in bipolar disorder: A review. Psychiatria Fennica. 1993;24:113–124. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SL, Roberts JE. Life events and bipolar disorder: Implications from biological theories. Psychological Bulletin. 1995;117:434–449. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein DN, Depue RA. Continued impairment in persons at risk for bipolar affective disorder: Results of a 19-month follow-up study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1984;93:345–347. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.93.3.345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovejoy MS, Steuerwald BL. Psychological characteristics associated with subsyndromal affective disorder. Personality and Individual Differences. 1992;13:303–308. [Google Scholar]

- Miklowitz DJ, Goldstein MJ, Nuechterlein KH, Snyder KS. Family factors and the course of bipolar affective disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1988;45:225–231. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1988.01800270033004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milich R, Hartung CM, Martin CA, Haigler ED. Behavioral disinhibition and underlying processes in adolescents with disruptive behavior disorders. In: Routh DK, editor. Disruptive behavior disorders in childhood. New York: Plenum Press; 1994. pp. 109–138. [Google Scholar]

- Newman JP, Patterson CM, Kosson DS. Response perseveration in psychopaths. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1987;96:145–148. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.96.2.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholls JG, Licht BG, Pearl RA. Some dangers of using personality questionnaires to study personality. Psychological Bulletin. 1982;92:572–580. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connell RA. Psychosocial factors in a model of manic-depressive disease. Integrative Psychiatry. 1986;4:150–154. [Google Scholar]

- Science. Neuroscience and mental illness. Science. 1992;257:1867. doi: 10.1126/science.257.5078.1867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverstone T, Romans-Clarkson S. Bipolar affective disorder: Causes and prevention of relapse. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1989;154:321–335. doi: 10.1192/bjp.154.3.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stallings MC, Hewitt JK, Cloninger CR, Heath AC. Genetic and environmental structure of the Tridimensional Personality Questionnaire: Three or four temperament dimensions? Journal of Personality & Social Psychology. 1996;70:127–140. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.70.1.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutton SK, Davidson RJ. Prefrontal brain asymmetry: A biological substrate of the behavioral approach and inhibition systems. Psychological Science. 1997;8:204–210. [Google Scholar]

- Weissman MM, Leaf PJ, Tischler GL, Blazer DG. Affective disorders in five United States communities. Psychological Medicine. 1988;18:141–153. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700001975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wise RA, Rompre PP. Brain dopamine and reward. Annual review of psychology. 1989;40:191–225. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ps.40.020189.001203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young R, Biggs J, Meyer D. A rating scale for mania: Reliability, validity, and sensitivity. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1978;133:429–435. doi: 10.1192/bjp.133.5.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]