Abstract

Bovine pancreatic ribonuclease A (RNase A) catalyzes the cleavage of P–O5′ bonds in RNA. Structural analyses had suggested that the active-site lysine residue (K41) may interact preferentially with the transition state for covalent bond cleavage, thus facilitating catalysis. Here, site-directed mutagenesis and semisynthesis were combined to probe the role of K41 in the catalysis of RNA cleavage. Recombinant DNA techniques were used to replace K41 with an arginine residue (K41R) and with a cysteine residue (K41C), which had the only sulfhydryl group in the native protein. The value of kcat/Km for cleavage of poly(C) by K41C RNase was 105-fold lower than that by the wild-type enzyme. The sulfhydryl group of K41C RNase A was alkylated with 5 different haloalkylamines. The value of kcat/Km for the resulting semisynthetic enzymes and K41R RNase A were correlated inversely with the values of pKa for the side chain of residue 41. Further, no significant catalytic advantage was gained by side chains that could donate a second hydrogen bond. These results indicate that residue 41 donates a single hydrogen bond to the rate-limiting transition state during catalysis.

Introduction

Illuminating the role of individual amino acid residues in enzymatic catalysis was made less problematic by the introduction of oligonucleotide-mediated site-directed mutagenesis.1 Since then, biological chemists have been able to exchange any one of the twenty naturally-incorporated amino acid residues for any other. Still, the common, natural amino acids display limited functionality. We report the use of cysteine elaboration to introduce nonnatural amino acid residues at a specific position in the active site of bovine pancreatic ribonuclease A (RNase A; E.C. 3.1.27.5).2-5 The advantage of such a strategy here is that nonnatural amino acid residues allow for greater variation in side-chain length and pKa than does standard oligonucleotide-mediated site-directed mutagenesis.

RNase A efficiently catalyzes the cleavage of the P–O5' bond of RNA specifically after pyrimidine residues (Figure 1).8 This enzyme has been the object of landmark work on enzymology; on the folding, stability, and chemistry of proteins; and on molecular evolution.9 Here, we have combined site-directed mutagenesis with semisynthesis to probe the role of the lysine residue at position 41 (K41). This residue was known from chemical modification11 and site-directed mutagenesis12 studies to be important for catalysis, but its precise role in catalysis had been unclear. Our results indicate that residue 41 donates a single hydrogen bond to the chemical transition state during RNA cleavage.

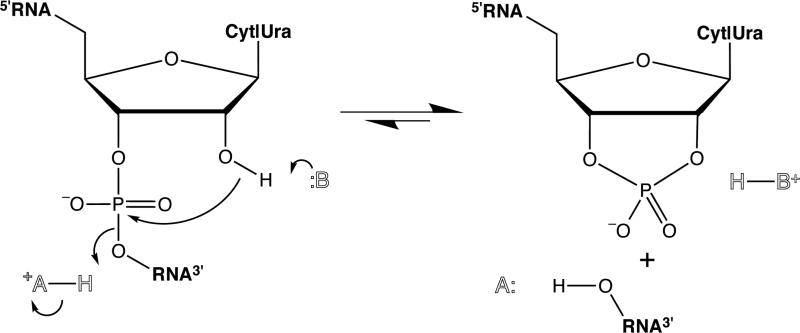

Figure 1.

Cleavage of RNA as catalyzed by RNase A.6 B is histidine 12; A is histidine 119.7

Results and Discussion

We used recombinant DNA techniques to produce an RNase A mutant in which K41 was changed to either a cysteine or an arginine residue. The change to cysteine introduces a solvent accessible sulfhydryl group to the native protein. (The other 8 cysteine residues form 4 disulfide bonds in native RNase A.) This sulfhydryl group was then alkylated with five haloalkylamines. In each of the resulting semisynthetic enzymes, residue 41 contains a nitrogen separated from the main chain by either 4 atoms (as in lysine) or 5 atoms (as in arginine). We then determined the ability of wild-type, mutant, and semisynthetic ribonucleases to catalyze the cleavage of polycytidylic acid [poly(C)].

The values of the steady-state kinetic parameters for cleavage of poly(C) by our ribonucleases are given in Table 1. The second-order rate constant, kcat/Km, is proportional to the association constant of an enzyme and the rate-limiting transition state during catalysis.13 We define the related free energy difference, ΔΔG‡, to report on the change in ability of each ribonuclease to bind to the rate-limiting transition state during catalysis. As shown in Table 1, dramatic differences are observed in the values of kcat/Km and ΔΔG‡, indicating that the mere presence of an alkylamine is not enough to effect efficient catalysis.

Table 1.

Steady-State Kinetic Parameters for the Cleavage of Poly(C) by Wild-Type, Mutant, and Semisynthetic Ribonucleases

| residue 41 | side chain | kcat (s–1) | Km (mM) | kcat/Km (M–1 s–1) | ΔΔG‡a | pKa of side chain NHb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cysteine | ~CH2–SH | 0.026 ± 0.004 | 0.36 ± 0.12 | 73 ± 15 | 6.8 | — |

| lysine (wild-type) | ~CH2CH2CH2CH2NH3+ | 604 ± 47 | 0.091 ± 0.022 | (6.5 ± 1.2) × 106 | 0.0 | 10.6 |

| S-(aminoethyl)cysteine | ~CH2–S–CH2CH2NH3+ | 43 ± 3 | 0.075 ± 0.016 | (5.2 ± 1.0) × 105 | 1.5 | 10.6 |

| S-acetamidinocysteine | ~CH2–S–CH2C(NH2)NH2+ | 11.0 ± 0.4 | 0.041 ± 0.006 | (2.6 ± 0.3) × 105 | 1.9 | 12.5 |

| S-(carbamoylmethyl)cysteine | ~CH2–S–CH2C(O)NH2 | 0.074 ± 0.007 | 0.25 ± 0.05 | 301 ± 28 | 5.9 | 15.2 |

| S-((trimethylamino)ethyl)cysteine | ~CH2–S–CH2CH2N(CH3)3+ | nd | nd | <230c | >6.1c | — |

| S-(aminopropyl)cysteine | ~CH2–S–CH2CH2CH2NH3+ | 12.9 ± 0.4 | 0.12 ± 0.01 | (1.1 ± 0.1) × 105 | 2.4 | 10.6 |

| arginine | ~CH2CH2CH2NHC(NH2)NH2+ | 4.4 ± 0.3 | 0.091 ± 0.016 | (4.8 ± 0.6) × 104 | 2.9 | 13.7 |

ΔΔG‡ = RTln[(kcat/Km)wild-type/(kcat/Km)].

Based on aqueous solutions of the model compounds: lysine, S-(aminoethyl)cysteine, S-(aminopropyl)cysteine, CH3CH2CH2CH2NH3+ (Hall, H. K., Jr. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1957, 79, 5441-5444); S-acetamidinocysteine, CH3C(NH2)NH2+ and arginine, H2NC(NH2)NH2+ (Albert, A. R.; Goldacre, R.; Phillips, J. J. Chem. Soc. 1948, 3, 2240-2249); S-(carbamoylmethyl)cysteine, CH3C(O)NH2 (Bordwell, F. G. Acc. Chem. Res. 1988, 21, 456-463).

Assuming Km ≥ 0.1 mM.

Structural Implications

The result of modifying the cysteine-containing mutant protein (K41C) with bromoethylamine is an enzyme quite closely related to wild-type RNase A. Yet, the value of kcat/Km for catalysis by K41S-ethylaminocysteine RNase A is only 8% that of the wild-type enzyme. The difference in the two proteins must lie in the differences between a thioether group and a methylene group. Although the angles of C–S–C bonds tend to be more acute than those of C–CH2–C bonds, this difference is offset by the greater length of C–S bonds.3g,14 Molecular modeling indicates that the primary amine groups in S-ethylaminocysteine and lysine can be superimposed to within 0.1 Å. A more significant difference between S-ethylaminocysteine and lysine is their relative preference for gauche rather than anti torsion angles.15 The anti conformation of CC–CC bonds is favored by approximately 0.8 kcal/mol in model compounds.16 Indeed, the average K41 torsion angle is (175 ± 3)° in the complex of RNase A with cyclic 2′,3′-uridine vanadate (U>v), a putative transition state analog (Figure 2). In contrast to CC–CC bonds, the gauche conformation of CS–CC bonds is favored by 0.05–0.20 kcal/mol.17 Molecular modeling indicates that the CS–CC bond of an S-ethylaminocysteine residue at position 41 can be in the gauche conformation without disturbing the structure of the native protein. Thus, the thioether side chains at position 41 are likely to be less rigid and extended than are the alkyl side chains. We therefore surmise that catalysis by the S-ethylaminocysteine enzyme is not as efficient as that by wild-type RNase A because of the entropic cost of fixing a thioether in the all anti conformation.

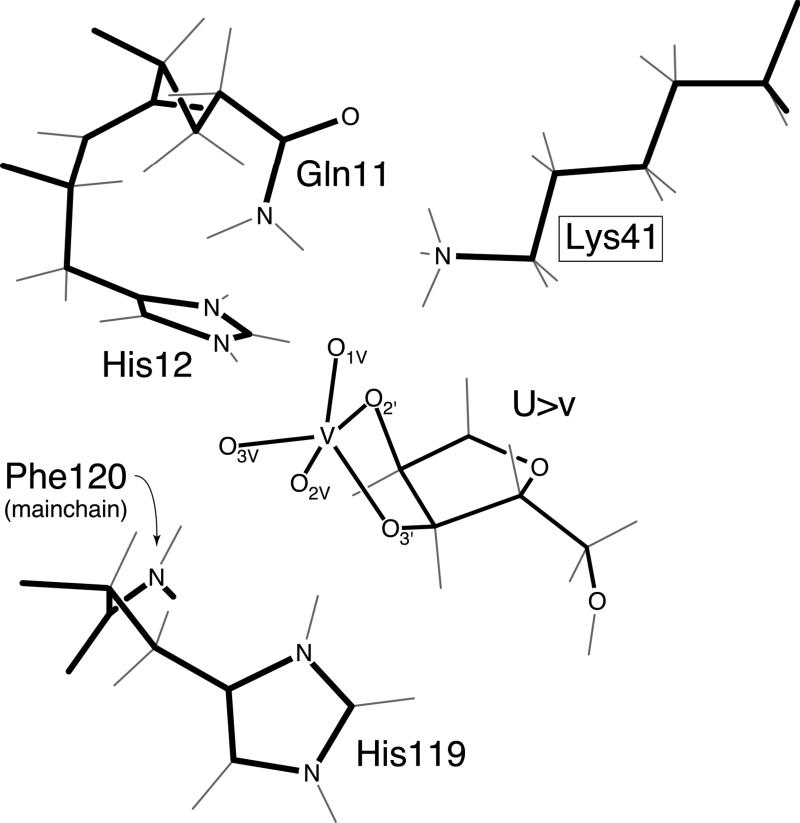

Figure 2.

Structure of the active site of RNase A bound to uridine 2′,3′-cyclic vanadate. The structure was refined at 2.0 Å from X-ray and neutron diffraction data collected from crystals grown at pH 5.3. The side chain of phenylalanine 120 and the uracil base are not shown.

Catalytic efficiency depends on the length of the side chain of residue 41. RNase A variants that present an amino group at the end of a side chain longer than that of lysine are more active catalysts than is unmodified K41C RNase A. Thus, additional length is tolerated in the active site. Still, enzymes in which an amino group at position 41 is separated from the main chain by 4 atoms are more active than are those separated by 5 atoms. This result could arise from the additional conformational entropy or unfavorable torsion angles of longer side chains.

No significant advantage is gained if residue 41 can donate a second hydrogen bond. Guanidino and acetamidino groups have the potential to interact simultaneously with more than one oxygen of a phosphoryl group. For example, a guanidino group is used to bind phosphoryl groups by the HIV-1 Tat protein18 and by artificial receptors.19 Further, in Staphylococcal nuclease and ribonucleases of the T1 family, an arginine appears to play the role of K41 in RNase A.20 We have replaced K41 with an arginine residue and an S-acetamidino residue, which is a short analog of arginine. The values of ΔΔG‡ for these enzymes are less than those for the analogous enzymes with only a primary amino group in the side chain of position 41. Thus, one hydrogen bond appears to be enough to effect efficient catalysis. This result is consistent with the crystalline complex of RNase A with U>v (Figure 2). The vanadyl group in U>v is an approximate trigonal bipyramid with two non-bridging equatorial oxygens, O1V and O3V. Oxygen O1V accepts a hydrogen bond from the side chain of glutamine 11 while O3V accepts a hydrogen bond from the main chain of phenylalanine 120. Only O1V is in position to accept a hydrogen bond from K41.

Mechanistic Implications. The catalytic role most commonly attributed to K41 is to stabilize the excess negative charge built up on the nonbridging phosphoryl oxygens during RNA cleavage (Figure 2). Charge build-up could occur in a pentacoordinate transition state (or phosphorane intermediate) when the 2′ hydroxyl group attacks the phosphorous, on the way to displacing the 5′ nucleoside. It has been assumed that this stabilization occurs by Coulombic interactions.12c,21 But, it has also been proposed recently that the stabilization occurs by way of a short, strong hydrogen bond involving the partial transfer of a proton from K41.22

The salient features of a lysine residue are its positive charge and its capacity to donate hydrogen bonds. Three of the 5 semisynthetic enzymes as well as K41R share these features. It is not a simple matter to differentiate between an interaction based solely on Coulombic forces and one based on hydrogen bonds between two charged species. What follows is the simplest explanation that is consistent with the data in Table 1.

The distinction between hydrogen bonds and Coulombic forces is most evident nowhere more than in a comparison of the S-ethyltrimethylaminocysteine enzyme, which possesses a terminal positive charge but no ability to donate a hydrogen bond, and the S-acetamidocysteine enzyme, which has an amide N–H for potential hydrogen bond donation but lacks a positive charge. The low catalytic activity of the S-ethyltrimethylaminocysteine enzyme argues strongly against the efficacy of Coulombic forces in transition state stabilization. All else being equal, the energy of a charge–charge interaction diminishes only as the inverse of distance. An increased distance between the positive charge on the side chain and the phosphoryl oxygens, relative to that in the S-ethylaminocysteine enzyme, is imposed by the methyl groups. Still, this distance is unlikely to be great enough to cause the observed >103-fold reduction in kcat/Km, especially since the three methyl group could readily be accomodated in the vicinity of the phosphoryl oxygens (Figure 2).

The strength of a hydrogen bond is expected to correlate inversely with the pKa of the proton being donated, inasmuch as hydrogen bonding involves some extent of proton transfer.23 As shown in Table 1, increases in pKa do indeed correspond to decreases in ΔΔG‡ for semisynthetic enzymes having side chains of comparable length. For those semisynthetic enzymes in which side chain lengths are comparable to lysine, the correlation is, however, nonlinear. This lack of linearity could arise because the pKa of each side chain depends on its particular environment in the native protein. Indeed, the pKa of Lys41 has been determined to be 9.0,24 rather than 10.6 as is listed for butylammonium ion in Table 1. Different side chains may be affected to different extents. Another, perhaps more significant, source of nonlinearity is that charged species tend to participate in stronger hydrogen bonds than do uncharged species. This phenomenon has been observed for proteins25 as well as small molecules, including amines.26 Comparing semisynthetic enzymes with side chains that are isosteric but differ in formal charge should reveal any such tendency. For example, in the S-acetamidinocysteine and S-acetamidocysteine enzymes, the side chains at position 41 are identical except for one of the two heteroatoms attached to the terminal carbon. Yet, the difference in the ability of these two isologous side chains to bind to the transition state is greater than that expected from their acidities alone. Here, the hydrogen bond donated from a charged acetamidine is 4 kcal/mol stronger than is that from an uncharged amide. This value is consistant with other data on the relative strengths of charged and uncharged hydrogen bonds in protein–ligand interactions.21 Finally, it is noteworthy that although the S-acetamido side chain lacks a formal charge and has a relatively high pKa, it still contributes (albeit modestly) to catalysis. This result provides further evidence of the importance to catalysis of a hydrogen bond donated by residue 41.

Conclusion

Site-directed mutagenesis followed by chemical modification has enabled us to study related enzymes that have more subtle changes in their active sites than would have been possible with site-directed mutagenesis alone. The correlation of high values of kcat/Km with low values of side-chain pKa and the low activity of the S-ethyltrimethylaminocysteine enzyme support a model in which the role of lysine 41 in catalysis by RNase A is to donate a strong hydrogen bond. Further, catalysis is not enhanced by the presence of a side chain at position 41 that can donate a second hydrogen bond. Finally, kinetic data are consistent with thioether side chains being less extended than alkyl side chains—lysine is not equivalent to S-ethylaminocysteine.

Experimental Section

Materials

Bromoethylamine·HBr, bromopropylamine·HBr, iodoacetamide, and bromoethyltrimethylamine·HBr were from Sigma Chemical (St. Louis, MO), and were used without further purification. Chloroacetonitrile and other chemicals used in the synthesis of chloroacetamidine·HCl were from Aldrich Chemical (Milwaukee, WI), and were used without further purification.

Chloroacetamidine·HCl was synthesized from chloroacetonitrile and ammonium chloride as described by Schaefer and Peters.27 Briefly, NaOCH3 was added to a solution of chloroacetonitrile in MeOH. A stoichiometric amount of ammonium chloride was then added to the solution of the imidate. Solvent was removed under vacuum, and the product was washed several times with diethyl ether and dried under vacuum. The integrity and purity of the chloroacetamidine·HCl was confirmed by 1H NMR (CD3OD; 4.85 ppm relative to tetramethylsilane, s, CH2), mass spectroscopy (EI, m/e 92; calcd. for C2H5ClN2 92.0141), and melting point determination (92–94 °C; uncorrected). Chloroacetamidine·HCl was found to be stable under vacuum for at least one week.

Enzyme preparation

Mutations in the cDNA that codes for RNase A were made by the method of Kunkel28 using oligonucleotides AAGGTGTTAACTGGCCTGCATCGATC (for K41R) and AAAGGTGTTAACTGGACAGCATCGATC (for K41C). Mutant cDNA's were expressed in Escherichia coli under the control of the T7 RNA polymerase promoter, and the resulting proteins were refolded and purified as described.29 The behavior of the K41C enzyme during FPLC suggests that the 4 native disulfide bonds form in high yield in this mutant enzyme. After purification, the new sulfhydryl group in the K41C enzyme was protected from inadvertant air oxidation by reaction with 5,5′-dithio-bis(2-nitrobenzoic acid) (DTNB). Prior to alkylation, the sulfhydryl group was deprotected by treatment with dithiothreitol (0.1 mM) for 25 min at 25 °C, or until one equivalent of 5-thio-2-nitrobenzoic acid had been released. Deprotected K41C RNase A was added to a freshly prepared solution of haloalkylamine (0.1 M) in 0.2 M Tris.HCl buffer, pH 8.3, and the resulting solution was incubated for 3 h at 30 °C. Semisynthetic enzymes were separated from any unreacted or undeprotected K41C by cation exchange FPLC (Mono S column; Pharmacia, Piscataway, NJ) using a linear gradient of NaCl (0–200 mM) in 50 mM HEPES buffer, pH 7.7. The isolated yield of each semisynthetic enzyme was at least 50%. Because of concerns about the stability of the acetamidino residue, the S-acetamidino enzyme was re-injected onto the FPLC column 10 days after it had been isolated and 8 days after kinetic parameters had been assayed. At this point, the enzyme still appeared to be >95% pure.

The following observations indicate that the alkylation reaction was specific for C41. First, no additional material eluted during cation exchange FPLC after the semisynthetic enzyme. Second, exposure of wild-type RNase A to the alkylation conditions did not change its catalytic activity.

Enzymatic Assays. Poly(C) was from Sigma Chemical or Midland Reagent (Midland, TX), and was purified by precipitation from aqueous ethanol (70% v/v). Assays of poly(C) cleavage were performed at 25 °C in 0.1 M Mes–HCl buffer, pH 6.0, containing NaCl (0.1 M). Cleavage of poly(C) was monitored by UV absorption using Δe = 2380 M–1cm–1 at 250 nm.8c Steady-state kinetic parameters were determined by fitting initial velocity data to a hyperbolic curve using the program HYPERO.30

Acknowledgment

This work was grant GM44783 (NIH). R.T.R. is a Presidential Young Investigator (NSF), Searle Scholar (Chicago Community Trust), and Shaw Scientist (Milwaukee Foundation).

References

- 1.a Hutchison CA, Phillips SA, Edgell MH, Gillam S, Jahnke P, Smith M. J. Biol. Chem. 1978;253:6551–6560. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Gillam S, Smith M. Gene. 1979;8:81–97. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(79)90009-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.For an early review of “semisynthesis” in enzymology, see: Kaiser ET, Lawrence DS. Science. 1984;226:505–511. doi: 10.1126/science.6238407.

- 3.For other applications of cysteine elaboration, see: Pease MD, Supersu EH, Mildvan AS. Fed. Proc. 1987;46:1932. Smith HB, Hartman FC. J. Biol. Chem. 1988;263:4921–4925. Lukac M, Collier RJ. J. Biol. Chem. 1988;263:6146–6149. Smith HB, Larimer FW, Hartman FC. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 152:579–584. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(88)80077-9. Planas A, Kirsch JF. Protein Eng. 1990;3:625–628. doi: 10.1093/protein/3.7.625. Smith HB, Larimer FW, Hartman FC. J. Biol. Chem. 1990;265:1243–1245. Planas A, Kirsch JF. Biochemistry. 1991;30:8268–8276. doi: 10.1021/bi00247a023. Sutton CL, Mazumder A, Chen CB, Sigman DS. Biochemistry. 1993;32:4225–4230. doi: 10.1021/bi00067a009. Wynn R, Richards FM. Protein Sci. 1993;2:395–403. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560020311. Dhalla AM, Li B, Alibhai MF, Yost KJ, Hemmingsen JM, Atkins WM, Schineller J, Villafranca J. J. Protein Sci. 1994;3:476–481. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560030313. Gloss LM, Kirsch JF. Biochemistry. 1995;34:3990–3998. doi: 10.1021/bi00012a017.

- 4.For reviews of the cysteine elaboration of ribulosebisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase, see: Hartman FC. In: Enzymatic and Model Carboxylation and Reduction Reactions for Carbon Dioxide Utilization. Aresta M, Schloss JV, editors. Kluwer Academic Publishers; The Netherlands: 1990. Hartman FC. In: Plant Protein Engineering. Shewry PR, Gutteridge S, editors. Cambridge University Press; New York, NY: 1992. Hartman FC. Adv. Enzymol. 1993;67:1–75. doi: 10.1002/9780470123133.ch1. Harpel MR, Larimer FW, Lee EH, Mural RJ, Smith HB, Soper TS, Hartman FC. In: Carbon Dioxide Fixation and Reduction in Biological and Model Systems, Proceedings of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences Nobel Symposium 1991. Brändén C-I, Schneider G, editors. Oxford University Press; New York, NY: 1994. Hartman FC, Harpel MR. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1994;63:197–234. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.63.070194.001213.

- 5.Several groups have introduced nonnatural amino acids into specific sites of proteins by using stop-codon suppressor tRNAs that have been charged in vitro. For leading references, see: Cornish VW, Schultz PG. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 1994;4:601–607.. We chose a semisynthetic route so as to generate large amounts of protein at little cost, and thereby allow for future structural analyses.

- 6.For other proposed mechanisms, see: Witzel H. Progr. Nucleic Acids Res. 1963;2:221–258. Hammes GG. Adv. Protein Chem. 1968;23:1–57. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3233(08)60399-x.; Wang JH. Science. 1968;161:328–334. doi: 10.1126/science.161.3839.328.; Anslyn E, Breslow R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1989;111:4473–4482.

- 7.Thompson JE, Raines RT. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994;116:5467–5468. doi: 10.1021/ja00091a060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.For recent work on the energetics and specificity of the reaction in Figure 1, see: Thompson JE, Venegas FD, Raines RT. Biochemistry. 1994;33:7408–7414. doi: 10.1021/bi00189a047.; Thompson JE, Kutateladze TG, Schuster MC, Venegas FD, Messmore JM, Raines RT. Bioorg. Chem. doi: 10.1006/bioo.1995.1033. Submitted for publication. delCardayré SB, Raines RT. Biochemistry. 1994;33:6031–6037. doi: 10.1021/bi00186a001. delCardayré SB, Raines RT. J. Mol. Biol. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0500. In press.

- 9.For reviews, see: Richards FM, Wyckoff HW. The Enzymes. 1971;4:647–806. Karpeisky MY, Yakovlev GI. Sov. Sci. Rev., Sect. D. 1981;2:145–257. Blackburn P, Moore S. The Enzymes. 1982;15:317–433. Wlodawer A. In: Biological Macromolecules and Assemblies, Vol. II, Nucleic Acids and Interactive Proteins. Jurnak FA, McPherson A, editors. Wiley; New York: 1985. pp. 395–439. Beintema JJ, Schüller C, Irie M, Carsana A. Prog. Biophys. Molec. Biol. 1988;51:165–192. doi: 10.1016/0079-6107(88)90001-6.

- 10.Alber T, Gilbert WA, Ponzi DR, Petsko GA. In: Mobility and Function in Proteins and Nucleic Acids. Porter R, O'Connor M, Whelan J, editors. Pitman; London: 1983. pp. 4–24. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murdock AL, Grist KL, Hirs CHW. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1966;114:375–390. [Google Scholar]

- 12.a Raines RT, Rutter WJ. In: Stucture and Chemistry of Ribonucleases. A. G. Pavlovsky A, Polyakov K, editors. USSR Academy of Sciences; Moscow: 1989. pp. 95–100. [Google Scholar]; b Raines RT. Structure, Mechanism and Function of Ribonucleases. Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona; Bellaterra, Spain: 1991. pp. 139–143. [Google Scholar]; c Trautwein K, Holliger P, Stackhouse J, Benner SA. FEBS Lett. 1991;281:275–277. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(91)80410-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Laity JH, Shimotakahara S, Scheraga HA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1993;90:615–619. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.2.615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Tarragona-Fiol A, Eggelte HJ, Harbron S, Sanchez E, Taylorson CJ, Ward JM, Rabin BR. Protein Eng. 1993;6:901–906. doi: 10.1093/protein/6.8.901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wolfenden R. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Bioeng. 1976;5:271–306. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.05.060176.001415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.For example, dimethyl sulfide: C–S 1.807 Å, angle CSC 99.05°; propane: C–C 1.532 Å, angle CCC 112° Lide DR, editor. CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics. 75th ed. CRC Press; Boca Raton, FL: 1994. pp. 9–31.pp. 9–37.

- 15.Gellman SH. Biochemistry. 1991;30:6633–6636. doi: 10.1021/bi00241a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Allinger NL, Yuh YH, Lii JH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1989;111:8551–8566. [Google Scholar]

- 17.a Sakakibara M, Matsuura H, Harada I, Shimanogouchi T. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1977;50:111–115. [Google Scholar]; b Oyanagi K, Kuchitsu K. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1978;51:2243–2248. [Google Scholar]; c Durig JR, Compton DAC, Jalilian MR. J. Phys. Chem. 1979;83:511–515. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Calnan BJ, Tidor B, Biancalana S, Hudson D, Frankel AD. Science. 1991;252:1168–1171. doi: 10.1126/science.252.5009.1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jubian V, Dixon RP, Hamilton AD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1992;114:1120–1121. [Google Scholar]

- 20.For leading references, see: Saenger W. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 1991;1:130–138.

- 21.a Roberts GCK, Dennis EA, Meadows DH, Cohen JS, Jardetzky O. Biochemistry. 1969;62:1151–1158. doi: 10.1073/pnas.62.4.1151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Flogel M, Biltonen RL. Biochemistry. 1975;14:2616–2621. doi: 10.1021/bi00683a009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Fersht A. Enzyme Structure and Mechanism. Freeman; New York: 1985. p. 431. [Google Scholar]

- 22.The proposal Gerlt JA, Gassman PG. Biochemistry. 1993;32:11943–11952. doi: 10.1021/bi00096a001. involves the sort of hydrogen bond that Cleland has called “low-barrier” Cleland WW, Kreevoy MM. Science. 1994;264:1887–1890. doi: 10.1126/science.8009219., and as such would require a pKa matched to the resulting transition state or a phosphorane dianion intermediate. The pKa's of the oxygens of a phosphorane triester were measured at 11.3 and 15. Anslyn E, personal communication.

- 23.a Gordy W, Stanford SC. J. Chem. Phys. 1941;9:204–214. [Google Scholar]; b Arnett EM. Prog. Phys. Org. Chem. 1963;1:223–403. [Google Scholar]; c Hine J. Structural Effects on Equilibria in Organic Chemistry. Wiley Interscience; New York: 1975. p. 200. [Google Scholar]; d Jencks WP. Catalysis in Chemistry and Enzymology. Dover Publications; New York: 1987. p. 338. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jentoft JE, Gerken TA, Jentoft N, Dearborn DG. J. Biol. Chem. 1981;256:231–236.. Also, the pKa of S-(aminoethyl)cysteine has been reported to be 9.5 Hermann VP, Lemke K. Hoppe-Seyler Z. Physiol. Chem. 1968;349:390–394.. In Table 1, we report the pKa's of appropriate model compounds rather than those of Lys41 or S-(aminoethyl)cysteine for the sake of internal consistency.

- 25.Fersht AR, Shi J-P, Knill-Jones J, Lowe DM, Wilkinson AJ, Blow DM, Brick P, Carter P, Waye MMY, Winter G. Nature. 1985;314:235–238. doi: 10.1038/314235a0. For reviews and leading references, see: Fersht AR. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1987;12:301–304. Rose GD, Wolfenden R. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 1993;22:381–415. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.22.060193.002121.

- 26.a Meot-Ner M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1984;106:1257–1264. [Google Scholar]; b Meot-Ner M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1986;108:7525–7529. doi: 10.1021/ja00284a014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schaefer FC, Peters GA. J. Org. Chem. 1961;26:412–418. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kunkel TA, Roberts JD, Zakour RA. Methods Enzymol. 1987;154:367–382. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(87)54085-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.delCardayré SB, Ribó M, Yokel EM, Quirk DJ, Rutter WJ, Raines RT. Protein Eng. 1995;8:261–273. doi: 10.1093/protein/8.3.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cleland WW. Methods Enzymol. 1979;63:103–138. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(79)63008-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]