Abstract

Rationale: Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is a major cause of lower respiratory tract infections in children, for which no specific treatment or vaccine is currently available. We have previously shown that RSV induces reactive oxygen species in cultured cells and oxidative injury in the lungs of experimentally infected mice. The mechanism(s) of RSV-induced oxidative stress in vivo is not known.

Objectives: To measure changes of lung antioxidant enzymes expression/activity and activation of NF-E2-related factor 2 (Nrf2), a transcription factor that regulates detoxifying and antioxidant enzyme gene expression, in mice and in infants with naturally acquired RSV infection.

Methods: Superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD 1), SOD 2, SOD 3, catalase, glutathione peroxidase, and glutathione S-transferase, as well as Nrf2 expression, were measured in murine bronchoalveolar lavage, cell extracts of conductive airways, and/or in human nasopharyngeal secretions by Western blot and two-dimensional gel electrophoresis. Antioxidant enzyme activity and markers of oxidative cell injury were measured in either murine bronchoalveolar lavage or nasopharyngeal secretions by colorimetric/immunoassays.

Measurements and Main Results: RSV infection induced a significant decrease in the expression and/or activity of SOD, catalase, glutathione S-transferase, and glutathione peroxidase in murine lungs and in the airways of children with severe bronchiolitis. Markers of oxidative damage correlated with severity of clinical illness in RSV-infected infants. Nrf2 expression was also significantly reduced in the lungs of viral-infected mice.

Conclusions: RSV infection induces significant down-regulation of the airway antioxidant system in vivo, likely resulting in lung oxidative damage. Modulation of oxidative stress may pave the way toward important advances in the therapeutic approach of RSV-induced acute lung disease.

Keywords: respiratory syncytial virus, airways, antioxidant enzymes, oxidative stress

AT A GLANCE COMMENTARY.

Scientific Knowledge on the Subject

Although respiratory viruses, such as respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), induce reactive oxygen species production and oxidative stress responses in cultured cells and experimental infections, the mechanisms of such oxidative injury and their role in the pathogenesis of natural infections in humans are not known.

What This Study Adds to the Field

This study suggests that RSV infections cause inhibition of lung antioxidant enzymes involved in maintaining the oxidant–antioxidant cellular balance. In children with naturally acquired RSV infections, such an event is associated with the presence of biomarkers of oxidative injury and with greater severity of clinical illness.

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is one of the most important causes of upper and lower respiratory tract infections in infants and young children. A recent metaanalysis has estimated that in 2005, 33.8 million new episodes of RSV-associated lower respiratory tract infections occurred worldwide in children younger than 5 years of age, with at least 3.4 million episodes representing severe RSV-associated infections necessitating hospital admission and up to 199,000 fatal cases (1). In the United States the number of children hospitalized each year with viral lower respiratory tract infections has recently been estimated at more than 200,000, with 500 deaths occurring per year in children under 5 years of age (2). The mechanisms of RSV-induced airway disease and associated long-term consequences remain incompletely defined, although lung inflammatory response is believed to play a central pathogenetic role. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are important regulators of cellular signaling (3, 4), and oxidative stress has been implicated in the pathogenesis of acute and chronic lung inflammatory diseases, such as asthma, cystic fibrosis, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (5–7). We have previously shown that RSV infection of airway epithelial cells induces ROS production, which is involved in transcription factor activation and chemokine gene expression (8, 9). We have also shown that RSV induces oxidative stress in the lung in a mouse model of experimental RSV infection, and that antioxidant treatment significantly ameliorates RSV-induced clinical disease and pulmonary inflammation (10). In addition, we found that RSV infection of airway epithelial cells results in a significant decrease of antioxidant enzyme (AOE) expression, as well as in increased levels of markers of oxidative stress, indicating an imbalance between ROS production and antioxidant cellular defenses (11). The molecular mechanism(s) responsible for RSV-induced oxidative damage in the airways in vivo is not known.

In this study, we found that expression of superoxide dismutase (SOD) 1 and 2, catalase, glutathione peroxidase (GPx), and glutathione S-transferase (GST) was significantly reduced in the bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) of mice infected with RSV. Similarly, enzymatic assays showed that total SOD, catalase, GPx, and GST activities were decreased in the lungs of infected animals. Indeed, proteomic analysis of murine BALs found that the decrease in AOE expression involved a large number of the enzymes involved in maintaining cellular oxidant–antioxidant balance. Lungs of mice infected with RSV showed a significant decrease in nuclear expression of Nrf2, a protein belonging to the cap-n-collar (CNC) family of transcription factors, which coordinates gene transcription of antioxidant and phase 2 metabolizing enzymes in response to oxidative stress (12). In nasopharyngeal secretions (NPS) of children with naturally acquired RSV infection, there was a significant increase in markers of oxidative injury and a significant decrease in AOE expression, which correlated with the severity of clinical illness. Our findings suggest that RSV-induced oxidative damage in vivo is the result of an imbalance between ROS production and airway antioxidant defenses. Modulation of oxidative stress represents a potential novel pharmacological approach to ameliorate RSV-induced acute lung inflammation and its long-term consequences. Some of the results of these studies have been previously reported in the form of an abstract (13).

METHODS

RSV Preparation

RSV A2 strain was grown in HEp-2 cells and purified by centrifugation on discontinuous sucrose gradients as described elsewhere (14). Titer of the purified RSV pools was 8 to 9 log10 plaque-forming units (PFU)/ml using a methylcellulose plaque assay. No contaminating cytokines were found in these sucrose-purified viral preparations (15). The human metapneumovirus (hMPV) strain CAN97-83 was propagated and titrated in LLC-MK2 cells and sucrose-gradient purified as previously described (16). Virus pools were aliquoted, quick-frozen on dry ice/alcohol, and stored at −80°C until used. Virus pools were endotoxin free by routine tests using the limulus hemocyanin agglutination assay.

Experimental Infection Protocol and Sample Collection

Female, 6- to 8-week-old BALB/c mice were purchased from Harlan (Houston, TX) and maintained in pathogen-free conditions at the animal research facility of the University of Texas Medical Branch (UTMB), Galveston, Texas. Mice were used under an experimental protocol approved by the UTMB Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Before inoculation with RSV, mice were lightly anesthetized by intraperitoneal administration of ketamine and xylazine. Mice were infected intranasally with 50 μl of RSV diluted in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; 107 PFU) or sham inoculated using the same volume of control buffer. For hMPV infection, mice were infected intranasally with 50 μl of hMPV (107 PFU). Groups of mice were killed at various intervals after infection and BAL was collected by flushing the lungs twice with ice-cold sterile PBS (1 ml) as described (10). BAL fluid was centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 2 minutes at 4°C and stored at −80°C until further analysis. Lungs were removed, quickly frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C until further processing.

RSV-Infected Children and Collection of Nasopharyngeal Secretion Samples

Sample of NPS were collected at UTMB from infants and children who were enrolled in an ongoing study on the pathogenesis of viral bronchiolitis. The study protocol and consent forms have been approved by the UTMB Institutional Review Board. The study population comprised groups of infants and children younger than 12 months old recruited from the UTMB Emergency Department, the pediatrics outpatient clinics, or inpatient areas of Children's Hospital. These subjects were assigned a diagnosis of upper respiratory tract infection (URTI) alone (absence of crackles or wheezing on auscultation of the chest, oxygen saturation ≥ 97% on room air, and normal chest radiograph when obtained), “nonhypoxic bronchiolitis” (defined for the purposes of this study as wheezing on auscultation with oxygen saturation > 95% on room air), or “hypoxic bronchiolitis” (wheezing on auscultation and oxygen saturation ≤ 95% on room air or, in the absence of wheezing, hyperinflation on chest radiograph and oxygen saturation ≤ 95% on room air). Hypoxia was assessed at the time that secretion samples were obtained, with subjects breathing ambient air without oxygen supplementation. Subjects with recurrent wheezing were not included, nor were those with history of chronic lung disease or congenital heart disease. Three infants who were intubated (VS, ventilatory support) because of acute respiratory failure caused by RSV infection were also included in the study. RSV infection was confirmed in all subjects by detection of viral antigen in NPS samples by antigen detection. All samples were obtained within the first 5 days of respiratory illness and within 24 hours after the onset of wheezing. Samples of NPS were obtained by passing size 5F feeding tubes into the nasopharynx and applying gentle suction. Secretions then were rinsed into collecting traps with 3 ml of PBS. After centrifugation to precipitate cells, samples were digested with sputolysin (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA), a mucolytic agent in 6.5 mM dithiothreitol in 100 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.01, and stored at −80°C for subsequent protein and biomarker analysis.

Extraction of Mouse Lung Nuclear and Epithelial Proteins

Lung nuclear proteins were prepared as previously described (17, 18). Briefly, mouse lung tissue was homogenized in 5 ml ice-cold Buffer A (10 mM 2-hydroxyethyl-piperazine N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid [HEPES]–KOH, pH 7.9, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM KCl, 0.5 mM dithiothreitol [DTT], 0.2 mM phemylmethyl sulfonyl fluoride [PMSF], 0.6% nonident P40 [NP-40]) and centrifuged at 350 × g, 4°C for 30 seconds. The supernatant was kept on ice for 5 minutes and centrifuged for 5 minutes at 6,000 × g at 4°C, and the pellet was resuspended in 200 μl Buffer B (10 mM HEPES–KOH, pH 7.9, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM KCl, 1.2 M sucrose, 0.5 mM DTT, 0.2 mM PMSF). After centrifugation (13,000 × g, 4°C, 30 min), the pellet was resuspended in 100 μl Buffer C (20 mM HEPES–KOH, pH 7.9, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 420 mM NaCl, 0.2 mM ethylenediamine-tetraacetic acid, 0.5 mM DTT, 0.2 mM PMSF, 2 mM benzamidine, 5 μg/ml leupeptin, 25% glycerol), incubated on ice for 20 minutes, and centrifuged (6,000 × g, 4°C, 2 min).

A lysis-lavage method described by Wheelock and colleagues was used to isolate epithelial cell proteins of conductive airways (19). Briefly, mice were killed and trachea was exposed and cannulated, lungs were then removed from the thorax and inflated with 0.5 ml agarose solution (0.75% low-melting agarose, 5% dextrose) immediately followed by 0.5 ml dextrose solution (1% dextrose, 2% protease inhibitor cocktail) through a three-way valve. Both solutions were preheated at 37°C. The inflated lungs were incubated in 5% dextrose for 15 minutes at room temperature. Dextrose solution was then removed by repeated steps of inversion of the lungs and gentle suction with a syringe. The airways were then lavaged with 0.5 ml of lysis buffer (2 M thiourea, 7 M urea, 4% 3-((3-cholamidopropyl)dimethylammonio)-1-propanesulfonic acid, 0.5% Triton X 100, 1% DTT, and protease inhibitors). The lysis buffer containing the proteins was immediately recovered, flash frozen on dry ice and stored at −80°C until further use.

Two-Dimensional Gel Electrophoresis and Gel Imaging

Mouse BAL fluids and sputolysin-digested human NPS samples were lyophilized and reconstituted in 100 μl of reagent 1 procured from Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA; 50 mM Tris buffer), desalted using protein desalting columns from Pierce (Rockford, IL) (7,000 MW cutoff), followed by albumin depletion by a Montage albumin depletion kit. Then 200 μl of 1 mg/ml protein aliquots were isoelectrofocused (IEF) on 11 cm–long nonlinear precast immobilized pH gradient (IPG) strips (pH 3–10; Bio-Rad) using the IPGPhor isoelectrofocusing system. Protein samples were loaded onto an IPG strip and rehydrated overnight. IEF was performed at 20°C with the following parameters: 50 V for 11 hours, 250 V for 1 hour, 500 V for 1 hour, 1,000 V for 1 hour, 8,000 V for 2 hours, and 8,000 V for 6 hours, with a total of 48,000 V. After IEF, the IPG strips were stored at −80°C until two-dimensional sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) was performed. For the two-dimensional SDS-PAGE, the IPG strips were incubated in 4 ml of equilibration buffer (6 M urea, 2% SDS, 50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.8], 20% glycerol) containing 10 μl of 0.5 M TCEP [Tris(2-carboxyethyl) phosphine] for 15 minutes at 22°C with shaking. The strips were then incubated in another 4 ml of equilibration buffer with 25 mg of iodoacetamide/ml for 15 minutes at 22°C with shaking. Electrophoresis was performed at 150 V for 2.25 hours at 4°C with 8 to 16% precast polyacrylamide gels in Tris-glycine buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl, 192 mM glycine, 0.1% SDS [pH 8.3]). After two-dimensional gel electrophoresis (2DE), the gels were fixed (10% methanol [MeOH], 7% acetic acid in double-distilled water), stained with SYPRO Ruby (Bio-Rad), and destained (10% ethanol in double-distilled water).

The destained gels were scanned at a 100-μm resolution using the Perkin-Elmer (Boston, MA) ProXPRESS ProFinder Proteomic Imaging System with 480-nm excitation and 620-nm emission filters. The exposure time was adjusted to achieve a value of approximately 55,000- to 63,000-pixel intensity on the most intense protein spots on the gel. The 2DE gel images were subsequently analyzed using Progenesis Discovery software version 2006.03 (Nonlinear Dynamics, Ltd., Newcastle Upon Tyne, UK). An average gel was created from gels run on BAL proteins from three separate samples from mock-infected mice (control) and three separate samples from RSV-infected mice (24 hours). For human samples, an average gel was created from gels run on NPS proteins from infants with URTI, nonhypoxic bronchiolitis, bronchiolitis with hypoxia, and patients on VS. The software automatically selected one of the six gels for mice experiment and one of the four gels for human NPS as the base image of the reference gel. The gel with the highest number of spots was set as the reference gel. Unmatched spots present in five of the six other gels were subsequently added to the reference gel image by the software to give a comprehensive reference gel. Subsequent to automatic spot detection, spot filtering was also manually performed. The matching of spots between the gels was manually reviewed and adjusted as necessary. Moreover, the log-transformed spot volumes were normally distributed, indicating that nonparametric statistical comparisons, such as t tests, could be applied to identify those proteins whose expression was significantly changed by infection. The spot volumes were normalized based on the total spot volume for each gel, and the control and RSV-infected samples were compared.

Protein Gel Spot Identification

Protein gel spots were excised and prepared for matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF-MS) analysis using Genomic Solutions' ProPic and ProPrep robotic instruments following the manufacturer's protocols. Briefly, gel pieces were incubated with trypsin (20 μg/ml in 25 mM ammonium bicarbonate, pH 8.0; Promega Corp., Madison, WI) at 37°C for 4 hours. The peptide mixture was purified with an in-tip reversed-phase column (C18 Zip-Tip; Millipore) to remove salts and impurities (20). MALDI-TOF-MS was performed using an Applied Biosystems Voyager model DE STR (Applied Biosystems, Framingham, MA) for peptide mass fingerprinting. The peptide masses were matched with the theoretical peptide masses of all the proteins from mouse and human species of the Swiss-Prot and National Center for Biotechnology database. Protein identification was performed using a Bayesian algorithm, in which high-probability matches are indicated by an expectation score, an estimate of the number of matches that would be expected in that database if the matches were completely random (21).

Western Blot Analysis

Equal amount of proteins (10–20 μg, depending on the antibody used) from mouse BAL, conductive airway epithelial cells or human NPS were loaded and separated by SDS-PAGE, and transferred onto Hybond-polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ). Nonspecific binding was blocked by immersing the membrane in Tris-buffered saline-Tween (TBST) blocking solution (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.6, 150 mM NaCl, 0.05% Tween-20 [v/v]) containing 5% skim milk powder for 30 minutes. After a short wash in TBST, the membranes were incubated with the primary antibody overnight at 4°C, followed by the appropriate secondary antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), diluted 1:5–10,000 in TBST for 1 hour at room temperature. After washing, the proteins were detected using enhanced-chemiluminescence assay (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. The primary antibodies used for Western blots were anti-SOD 1, 2, and 3 rabbit polyclonal antibodies (Stressgen Bioreagents, Ann Arbor, MI), anti-catalase rabbit polyclonal antibody, and anti-lamin B mouse monoclonal antibody (Calbiochem), anti-Nrf2 (C20) rabbit polyclonal (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and anti–β-actin mouse monoclonal antibody from Sigma-Aldrich (Saint Louis, MO). The anti-GST rabbit polyclonal antibody was a generous gift from Dr. Yogesh Awasthi, University of North Texas Health Science Center.

Biochemical Assays for Antioxidant Activities

Catalase, GST, GPx, and SOD activities were determined in BAL fluids using specific biochemical assays (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI; Catalog No. 707002, 703302, 703102, and 706002, respectively, for catalase, GST, GPx, and SOD), according to the manufacturer's instructions. The quantification of catalase activity in BAL was based on the reaction of the enzyme with methanol in the presence of an optimal concentration of H2O2. The formaldehyde produced is measured spectrophotometrically with 4-amino-3-hydrazino-5-mercapto-124-triazole as the chromogen. The catalase activity was expressed as nmol/min/mg of protein in the sample. The total GST activity was quantified by measuring the conjugation of 1-chloro-2,4-dinitrobenzene with reduced glutathione. The conjugation is accompanied by an increase in absorbance at 340 nm. The rate of increase is directly proportional to the GST activity in the sample. The GST activity was expressed as nmol/min/mg of protein in the sample. The GPx activity was determined spectrophotometrically in BAL through an indirect coupled reaction with glutathione reductase. Oxidized glutathione, produced on reduction of hydroperoxide by GPx, is recycled to its reduced state by glutathione reductase and NADP reduced. The oxidation of NADP reduced to NADP+ is accompanied by a decrease in absorbance at 340 nm. Under conditions in which the GPx activity is rate limiting, the rate of decrease in the A340 is directly proportional to the GPx activity in the sample. SOD activity was determined by using tetrazolium salt for the detection of superoxide radicals generated by xanthine oxidase and hypoxanthine. One unit of SOD is defined as the amount of enzyme needed to exhibit 50% dismutation of the superoxide radical.

Measurement of Lipid Peroxidation Products

Measurement of F2 8-isoprostane in human NPS was performed using a competitive enzyme immunoassay from Cayman Chemical Co. according to manufacturer's instructions. Measurement of malondialdehyde (MDA) was performed using a spectrophotometric assay (Oxis Research, Burlingame, CA).

Statistical Analysis

All results are expressed as mean ± SEM. Data were analyzed using the GraphPad Instat Biostatistics 3.0 software. Student t test using a 95% confidence level was used to determine the level of differences in RSV-infected versus sham-inoculated mice. Differences between RSV illness groups were assessed by use of ANOVA.

RESULTS

Expression of AOE in the Lung Is Decreased by RSV Infection

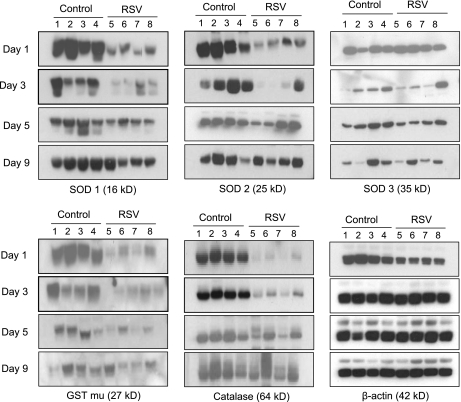

ROS generation due to the respiratory burst of activated phagocytic cells recruited to the airways during viral infections is an important antiviral defense. However, a robust production of ROS can lead to depletion of antioxidants and cause oxidative stress. In previous studies, we have shown that RSV infection causes significant oxidative stress damage as demonstrated by the increase of the lipid peroxidation markers F2 8-isoprostane, MDA, and 4-hydroxynonenal in cultured airway epithelial cells and in the lung of experimentally infected mice (8, 10). More recently, we have demonstrated a significant reduction in the expression of several antioxidant enzymes, such as SOD 1, SOD 3, catalase, and GST, in airway epithelial cells as a result of RSV infection, suggesting that oxidative stress could be the result of imbalance between ROS production and antioxidant cellular defenses (11). To determine whether RSV infection results in decreased expression of antioxidant proteins in vivo, similar to our observation in cultured cells, groups of BALB/c mice were infected intranasally with RSV or sham-inoculated. BAL was collected at Days 1, 3, 5, and 9 after infection to assess levels of catalase, GST-mu, and SOD 1, 2, and 3 by Western blot. As shown in Figure 1 and by densitometric analysis in Figure E1 in the online supplement, RSV-infected mice showed a significant reduction in the expression levels of most of the tested enzymes at Days 1 and/or 3 after infection compared with control animals. SOD 3 was decreased at Days 3 and 5 after infection in most but not all of the RSV-infected animals and therefore did not reach statistical significance. Overall, levels of AOE in RSV-infected mice returned to control levels by Day 9 after infection, with the exception of SOD 2, whose expression normalized earlier (Day 5 after infection). A similar reduction in AOE expression in the lung was also observed in mice infected with hMPV, a paramyxovirus that causes a significant proportion of lower respiratory tract infections in young infants and children (22) (Figure E4).

Figure 1.

Antioxidant enzymes are reduced in bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV)-infected mice. Groups of mice were infected with RSV or sham inoculated with saline (Control) and BAL was collected at Days 1, 3, 5, and 9. BAL proteins were resolved on 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and Western blots were performed using antibodies against superoxide dismutase (SOD) 1, SOD 2, SOD 3, catalase, and glutathione S-transferase (GST)-mu. Membranes were stripped and reprobed for β-actin as an internal control for protein integrity and loading. Lanes 1 to 4 are BAL from four control and 5 to 8 from four RSV-infected mice at each time point. Densitometric analysis of Western blot band intensities is presented in Figure E1. The figure is representative of three independent experiments, each experiment with four mice per group at each time point.

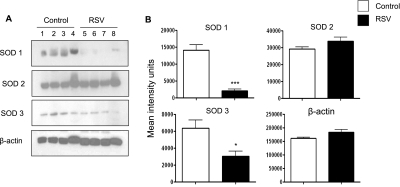

To determine whether levels of AOE detected in the BAL reflected changes in the AOE in airway epithelium, a major target of RSV infection, we performed Western blot analysis of SOD 1, 2, and 3 in proteins isolated from airway epithelial cells of infected mice. We found a significant decrease of SOD 1 and 3 in epithelial proteins of RSV-infected mice compared with epithelial proteins from control mice (Figure 2). On the other hand, SOD 2 levels were similar in epithelial proteins of RSV-infected and control mice, suggesting that the reduction of such enzymes observed in Western blots of infected BAL samples may reflect a nonepithelial source/cell target of such enzymes after RSV infection (see Discussion).

Figure 2.

Superoxide dismutase (SOD) 1, SOD 2, and SOD 3 in conductive airway epithelial cells. (A) Proteins of conductive airway epithelial cells were obtained by lysis-lavage from respiratory syncytial virus (RSV)-infected or control mice (Day 1 after infection). Proteins were analyzed by Western blot for content of SOD 1, SOD 2, and SOD 3 as in Figure 1. (B) Densitometric analysis of Western blot band intensities was performed using Alpha Ease software, version 2200 (2.2d) (Alpha Innotech Co., San Leandro, CA). Bands in RSV-infected samples were normalized to uninfected control sample background and are presented as mean ± SEM of n = 4. *P < 0.05; ***P < 0.001 relative to control mice.

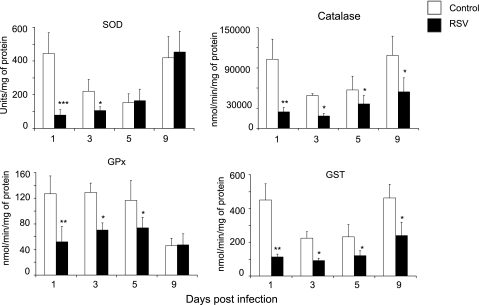

RSV Infection Decreases Lung AOE Activities

To determine whether changes in AOE protein expression resulted in changes in their activities in response to RSV infection, BAL was collected from groups of RSV-infected or sham-inoculated mice at Days 1, 3, 5, and 9 after infection, and total SOD, catalase, GST, and GPx enzymatic activity were assessed by biochemical assays. There was a significant reduction of all AOE activities in RSV-infected mice compared with control animals (Figure 3). In particular, in RSV-infected mice, total SOD and GPx activities decreased significantly at Days 1 (86 and 59%, respectively) and 3 (52 and 46%, respectively), compared with sham-inoculated mice, with levels returning to those in control mice by Day 9. In addition, catalase and GST activities were significantly lower in RSV-infected mice compared with control mice at all tested time points, but different from our findings with SOD and GPx, they did not return to control levels by Day 9 (76, 63, 37, and 50% reduction for catalase and 75, 59, 50, and 48% reduction for GST at Days 1, 3, 5, and 9 after infection). Overall, these results indicate that RSV significantly reduces antioxidant defenses of the airways.

Figure 3.

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infection inhibits antioxidant enzyme activity in the lung. Specific biochemical assays were used to determine total superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase, glutathione peroxidase (GPx), and glutathione S-transferase (GST) activity in bronchoalveolar lavage of groups of mice that were RSV infected or sham inoculated as in Figure 1. The figure is representative of three independent experiments, each experiment with four to five mice per group at each time point. Data are presented as mean ± SEM of four mice per group at each time point. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001 relative to control mice.

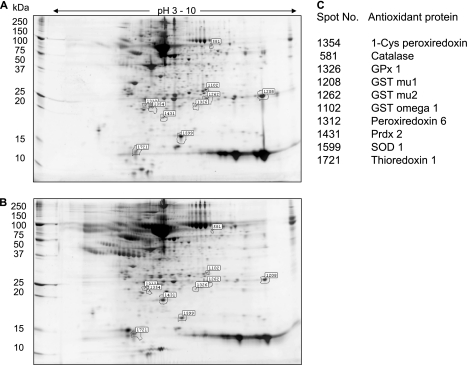

Global Proteomic Analysis of AOE Expression in BAL

In recent years, proteomic analysis has advanced our knowledge of BAL proteins and their degradation products present at the alveolar level. These proteins may be plasma derived or locally produced and are released under normal or pathological conditions by inflammatory, immune, and tissue-resident cells (23). Thus, with the intent to gain a more global insight into the lung antioxidant response in the course of a viral infection, we investigated differential protein expression in BAL of RSV-infected mice compared with control uninfected animals by 2DE. Comparison of SYPRO Ruby-stained 2DE gels of RSV-infected and uninfected BAL proteins showed significant changes in the protein spot profile, as shown in the master gel images of 2DE BAL proteins from control (Figure 4A) and RSV-infected mice (Figure 4B) at Day 3 after infection. Overall, more than 1,300 protein spots with pH range 3 to 10 and relative molecular masses range of 10 to 250 kD were detected on our 2DE. BAL protein spots found to be significantly different in expression level between RSV-infected and control mice (either increased or decreased) were excised from the gels, trypsinized, and analyzed by MALDI-TOF-MS. Among the spots that we were able to identify with high probability score there were several antioxidant enzymes that were decreased in the BAL of RSV-infected mice compared with control mice. We found reduced expression of several other AOE, including peroxiredoxin enzymes (listed with their corresponding spot number in Figure 4C), in addition to catalase, SOD 1, GPx 1, and GST-mu (whose change in expression is better shown in Figure E2). Table 1 summarizes all antioxidant proteins whose expression in BAL changed during the course of RSV infection. Most of the AOE levels were significantly reduced as early as Day 1 (with the exception of peroxiredoxin 2), and they were significantly lower throughout the acute phase of RSV infection, compared with control mice, to return to basal or slightly above basal levels by Day 25 after infection. Thioredoxin 1 was the only AOE substantially unchanged in infected mice compared with control mice. These results confirm and extend our findings by Western blots, indicating that RSV significantly diminishes antioxidant defenses in the lung.

Figure 4.

Two-dimensional gel electrophoresis (2DE) of bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) proteins reveals a global reduction in antioxidant enzyme expression after respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infection. SYPRO Ruby–stained 2DE of BAL from (A) control and (B) RSV-infected mouse at Day 3 after infection Desalted and albumin-depleted proteins (200 μl at 1 mg/ml concentration) were fractionated over immobilized pH gradients from 3 to 10 in the horizontal dimension, followed by sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis in the vertical dimension. Left, migration of molecular mass standards (kDa). The spot volumes were normalized based on the total spot volume for each gel, and the control and RSV-infected samples were compared. The numbers indicate differentially expressed spots identified by tryptic peptide mass fingerprinting and listed in C.

TABLE 1.

DIFFERENTIAL EXPRESSION OF ANTIOXIDANT ENZYMES IN BAL OF MICE BY TWO-DIMENSIONAL GEL ELECTROPHORESIS

| Fold Change in RSV BAL Compared to Control |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AOE | Day 1 | Day 3 | Day 5 | Day 9 | Day 25 |

| 1-Cys peroxiredoxin protein | −1.0 | −6.1 | — | −4.1 | — |

| Catalase | — | −2.5 | −2.1 | — | — |

| Cu/Zn SOD 1 | −2.3 | −3.4 | −2.0 | −2.0 | — |

| Glutathione peroxidase 1 | −1.8 | −2.3 | — | 1.3 | — |

| Glutathione S-transferase | — | — | — | −6.0 | — |

| Glutathione S-transferase omega 1 | −6.8 | −3.6 | −2.3 | −2.0 | 1.3 |

| Glutathione S-transferase, alpha 4 | −2.2 | — | — | — | — |

| Glutathione S-transferase, mu 1 | — | −4.0 | −7.0 | −1.7 | 1.4 |

| Glutathione S-transferase, mu 2 | — | −4.3 | — | 3.4 | −1.3 |

| Glutathione-disulfide reductase | — | — | — | 3 | — |

| Nonselenium glutathione peroxidase | −2.6 | — | −4.2 | −1.3 | 1.2 |

| Peroxiredoxin 6 | — | −3.1 | −3.9 | −4.1 | 1.3 |

| Peroxiredoxin 2 | 2.7 | 2.4 | −2.1 | 1.7 | — |

| Thioredoxin 1 | — | 1.5 | — | — | 1.1 |

Definition of abbreviations: AOE = antioxidant enzymes; BAL = bronchoalveolar lavage; RSV = respiratory syncytial virus; SOD = superoxide dismutase; 2DE = two-dimensional gel electrophoresis.

Shown are fold changes of spot volume/intensity in RSV-infected over control mice. Listed AOE protein spots were identified based on high-probability from peptide mass fingerprinting in MALDI-TOF-MS (Expectation score). — indicates a protein spot that was not excised from the 2DE gel for mass fingerprinting.

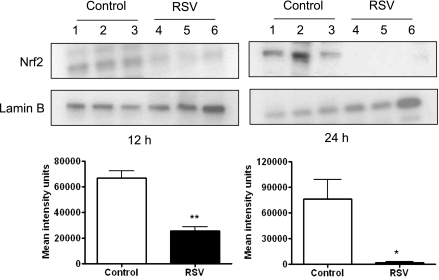

RSV Infection Modifies the Expression of Transcription Factor Nrf2 in Mouse Lung Nuclear Extracts

Recent findings have demonstrated that Nrf2 is a crucial transcription factor that binds to antioxidant responsive element (ARE) sequences and regulates the expression of antioxidant and phase 2 metabolizing enzymes in response to oxidative stress (12) (24, 25). To examine the effect of RSV infection on Nrf2 activation, we performed Western blot analysis of mouse lung nuclear extracts. Groups of BALB/c mice were infected with RSV or sham inoculated, and nuclear extracts were obtained from lungs at 12, 24, 48, and 72 hours after infection. There was a significant decrease of Nrf2 nuclear abundance in RSV-infected mice compared with control mice at 12 hours and 24 hours after infection (average percentage change of Nrf2 in RSV over control is 61 and 97% at 12 and 24 hours, respectively) (Figure 5), with nuclear levels in RSV-infected mice still below control at 48 and 72 hours after infection (data not shown). These results suggest that decreased AOE expression after RSV infection could be due to reduced basal activation of Nrf2 in the airways of mice.

Figure 5.

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infection is associated with decreased levels of nuclear Nrf2 in the lung. Mice were infected with RSV or sham inoculated and lungs were harvested at 12 and 24 hours to isolate nuclear proteins. Equal amounts of nuclear proteins were analyzed by Western blot using anti-Nrf2 antibody. Membranes were stripped and reprobed for Lamin B, as control for equal loading of the samples. Lanes 1 to 3 are lung nuclear proteins from control and 4 to 6 from RSV-infected mice at each time point. The figure is representative of three independent experiments, each experiment with four to five mice per group at each time point. Densitometric analysis of Western blot band intensities was performed using Alpha Ease software presented as mean ± SEM of n = 3. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01 relative to control mice.

Oxidative Stress Markers and AOE in Children with RSV Infection

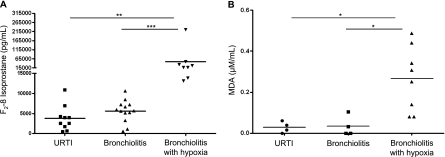

We have previously shown that RSV is a potent inducer of ROS in airway epithelial cells in vitro (8) and causes significant oxidative stress damage in vivo, as demonstrated by the increase of lipid peroxidation markers F2 8-isoprostane, MDA, and 4-hydroxynonenal in the lung of experimentally infected mice (10). These data along with the findings presented herein showing a global down-regulation of the lung antioxidant capacity as a consequence of RSV infection prompted us to conduct a study in children to determine whether the virus is capable of inducing oxidative stress damage in naturally acquired infections. Thus, we measured the levels of F2 8-isoprostane and MDA in NPS of children with RSV-proven infections of increasing clinical severity, from milder URTI to bronchiolitis without or with hypoxia (demographics of the study population described in Table 2). The group of children with hypoxic bronchiolitis included also three subjects who required intubation and VS because of respiratory failure. As shown in Figure 6A, concentration of F2 8-isoprostane in NPS was slightly increased in subjects with mild bronchiolitis compared with those with URTI, but the difference was not statistically significant. However, subjects with hypoxic bronchiolitis had significantly more F2 8-isoprostane in NPS than did subjects with URTI alone (P < 0.01) or with nonhypoxic bronchiolitis (P < 0.001). A similar trend was observed for MDA concentrations in a smaller number of NPS samples that were tested (Figure 6B).

TABLE 2.

CHARACTERISTICS OF STUDY PATIENTS WITH RESPIRATORY SYNCYTIAL VIRUS INFECTION, BY ILLNESS GROUP

| Study Patient Characteristics | URTI Alone | Bronchiolitis | Hypoxic Bronchiolitis |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of subjects | 10 | 13 | 8 |

| Age, mean months | 6.4 | 6.3 | 9.7 |

| Boys:girls | 5:5 | 8:5 | 4:4 |

| Race | |||

| White | 0 | 4 | 2 |

| Black | 0 | 2 | 4 |

| Hispanic | 9 | 5 | 2 |

| Others | 1 | 2 | 0 |

Definition of abbreviations: URTI = upper respiratory tract infection.

Figure 6.

Concentrations of the oxidative stress markers in nasopharyngeal secretions (NPS) of infants with naturally acquired respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infections. NPS collected from infants and young children with RSV-proven upper respiratory tract infections (URTI) and bronchiolitis were tested for (A) F2-isoprostane or (B) malondialdehyde (MDA) concentrations. Horizontal lines indicate the mean concentration. **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001 compared with URTI.

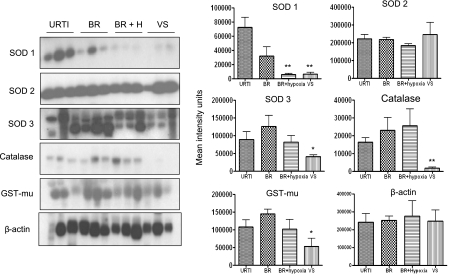

To determine whether natural RSV infection along with an oxidative stress response may cause reduction of antioxidant defenses as we observed in experimentally infected mice, we measured levels of SOD 1, 2, and 3, catalase, and GST-mu in NPS of infected children by Western blot (Figure 7). For this analysis, infants on VS (i.e., those with most severe illness) were included in a separate group. SOD 1 levels were lower in infants with bronchiolitis, hypoxic bronchiolitis, and VS compared with those with URTI alone. The VS group showed also significantly lower levels of SOD 3, catalase, and GST-mu compared with the other illness groups. SOD 2 levels were similar in all illness groups.

Figure 7.

Antioxidant enzyme expression in nasopharyngeal secretions (NPS) of infants with naturally acquired respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infections. (A) Western blot analysis of superoxide dismutase (SOD) 1, SOD 2, and SOD 3, catalase, and glutathione S-transferase (GST)-mu in NPS of children with upper respiratory tract infections (URTI), bronchiolitis (BR), bronchiolitis with hypoxia (BR + H), and patients on ventilatory support (VS). β-actin was used as a control for protein integrity and equal loading of the samples. Densitometric analysis of Western blot band intensities was performed using Alpha Ease software. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01, compared with URTI.

To further investigate the spectrum of AOE changes in NPS samples from RSV-infected children, NPS proteins from the four groups described above were separated by high-resolution 2DE followed by MALDI-TOF-MS. We found that the antioxidant protein spots corresponding to SOD 1 and catalase were clearly present in URTI and bronchiolitis but significantly decreased in patients with hypoxic bronchiolitis and patients on VS, in agreement with the data of the Western blot analysis. Peroxiredoxin 1 expression was also significantly lower in children with bronchiolitis with hypoxia and VS compared with those with URTI and bronchiolitis (Figure E3).

DISCUSSION

Free radicals and ROS have been shown to function as cellular signaling molecules influencing a variety of molecular and biochemical processes, including expression of proinflammatory mediators, such as cytokines and chemokines (reviewed in Reference 4). However, excessive ROS formation can lead to a condition of oxidative stress, which has been implicated in the pathogenesis of several acute and chronic airway diseases, such as asthma and COPD (reviewed in References 26 and 27). Inducible ROS generation has been shown after stimulation with a variety of molecules and infection with certain viruses, such as HIV, hepatitis B, influenza, and rhinovirus (reviewed in Reference 28). We have recently shown that RSV infection of airway epithelial cells induces ROS production, in part through an NAD(P)H oxidase-dependent mechanism, inducing oxidative stress in vitro (11) and in vivo (10), and that antioxidant treatment blocks transcription factor activation and chemokine gene expression in vitro (8, 9, 29) and ameliorates RSV-induced clinical illness in vivo (10), indicating a central role of ROS in RSV-induced cellular signaling and lung disease. Although there is increasing evidence that generation of oxidative stress is linked to the pathogenesis of a variety of acute and chronic inflammatory lung diseases, little is known regarding the role of oxidative stress in viral-induced lung diseases and the effect of respiratory viruses on AOE expression and/or activity. In the present study, we investigated whether RSV-induced lung oxidative stress in vivo, defined as a disruption of the prooxidant–antioxidant balance in favor of the former, could be due to an impairment of the antioxidant defense systems and whether increased oxidative stress could play a role in RSV-associated lung disease severity. Our results show that RSV infection induces a significant decrease in the expression of most AOE involved in maintaining cellular oxidant–antioxidant balance in mice and children, with the exception of SOD 2, for which levels are reduced in the BAL of infected mice but not in epithelial cell proteins of the conductive airways or in NPS of infected children, suggesting that airway epithelial cells may not be the only cellular source of the lung antioxidant response measured in BAL of mice. Other tissue resident cells, such as alveolar macrophages, which are early targets of RSV infection (30), could contribute to the observed BAL findings.

Similar to RSV, hMPV, a recently identified paramyxovirus, induces a progressive decrease of AOE expression levels in airway epithelial cells (31) and in the lung of infected mice as showed herein (Figure E4). In other studies, total lung SOD and catalase activities have been shown to be reduced in mice after influenza infection (32), supporting the knowledge that oxidative stress plays a significant role in the pathogenesis of influenza-induced pneumonia (33, 34). On the other hand, rhinovirus infection of bronchial epithelial cells has been shown to induce ROS formation (35) and to increase SOD 1 expression and total SOD activity at early time points of infection, with no changes in SOD 2, catalase, and GPx (36), although AOE expression/activity was investigated only at 6 hours after infection. Regarding other noninfectious conditions, an increase in antioxidant defenses has been shown to occur in certain pulmonary diseases with significant oxidant burden, such as exposure to hyperoxia (37), ozone (38), and cigarette smoke (39), although decreased antioxidant expression and/or activity has been reported in other respiratory acute and chronic inflammatory disease, such as asthma and COPD (40–43). Reduced SOD and catalase activity has been shown in airway epithelial cells and/or bronchoalveolar lavage obtained from patients with asthma (40–42). Similarly, decreased catalase and GST expression has been found in the lungs of COPD patients in association with chronic smoke exposure (43). Low dietary intake of antioxidants, including vitamins C and E, has been associated with worse symptoms in children with asthma (44).

The mechanism leading to decreased expression/activity of AOE is not clear. SOD 3 and catalase expression has been shown to be negatively regulated in response to cytokine stimulation, such as interleukin-1, tumor necrosis factor-α, and interferon-γ (45). Furthermore, oxidative stress can lead to SOD and catalase inactivation, as it has been shown in the BAL of patients with asthma (42). Nrf2 is a central transcription factor regulating the expression of a variety of cytoprotective genes involved in detoxification of xenobiotics and in counteracting cellular oxidative stress, including inducible AOE genes (reviewed in Reference 46). In this study, we have observed that RSV infection leads to a progressive decrease in the nuclear protein levels of Nrf2, suggesting a potential mechanism for down-regulation of AOE gene expression. Reduced nuclear levels of Nrf2 can occur as a result of various mechanisms, including decreased expression or increased degradation or through increased nuclear export (47). As Nrf2 positively regulates its own gene transcription, there are reduced Nrf2 mRNA levels in airway epithelial cells at a late time point of RSV infection, as we recently published (11). However, it is likely that other mechanisms contribute to the decreased Nrf2 nuclear levels at the earlier time points of infection. A recent study has shown that the Nrf2-ARE pathway plays a protective role in the murine airways against RSV-induced injury and oxidative stress (48). More severe RSV disease, including higher viral titers, augmented inflammation, and enhanced mucus production and epithelial injury, were found in Nrf2−/− mice compared with Nrf2+/+ mice. Significant down-regulation of Nrf2 mRNA expression has been observed in pulmonary macrophages of aged smokers and patients with COPD (49), and functional polymorphisms in the Nrf2 gene promoter, leading to reduced gene transcription, are associated with the severity of COPD (50) and increased risk of acute lung injury after trauma (51).

In our initial study of NPS obtained from children with RSV infection, we found a significant increase in markers of oxidative injury and a significant decrease in AOE expression, which correlated with the severity of lung disease. In previous studies of patients with RSV infection we have shown that concentration of certain inflammatory mediators and cytokines in NPS, many of which are of epithelial origin, correlate with their concentration in the lower airway (52). We therefore speculate that ROS or oxidative stress marker production measured in the NPS samples may reflect the events occurring in the lower airways. Although our study was performed in a relatively small cohort of RSV-infected subjects, it included a balanced representation of the spectrum of disease that is caused by this pathogen in infancy. Since viral culture or real-time PCR for other viral pathogens in samples that were positive for RSV antigen were not performed, the potential effect of single RSV versus dual infections on oxidative stress responses and AOE expression cannot be answered at this point. Also, our data in mice suggest that infections caused by other viral respiratory pathogens, which are known to cause bronchiolitis in infants, may also result in a similar inhibition of AOE expression. To unequivocally answer this question there is a need for larger clinical studies. In this regard, we are currently enrolling infants in a prospective study in which patients with a broad spectrum of disease severity caused by RSV or by other viral agents will be tested.

Other important aspects in future studies of RSV infections compared with those caused by other pathogens include the actual profile of AOE that are altered in expression, either decreased or increased in severe versus milder forms of infection, the ability of each pathogen to trigger the generation of ROS, and the “magnitude” and type of oxidative damage in the airways, including the presence of other lipid peroxidation products or protein modifications, which characterize the biological targets of ROS formation. Also, the known developmental process of the AOE system that starts during fetal life and is characterized by a certain degree of immaturity in the neonatal period and early infancy may contribute to the severity of RSV infections that occur during this vulnerable period of life (53). All these factors are likely to contribute to the oxidative-mediated pathogenesis of viral bronchiolitis and perhaps to the relative greater effect of a pathogen (for example RSV) compared with others. With even broader implications, generation of such an oxidative stress environment in the airways, along with the impaired antioxidant response that we describe as result of paramyxovirus infections, may induce critical chemical modifications of bystander antigens and their immunogenicity. Such a possibility has been suggested by studies of aldehyde-mediated carbonylation of protein allergens resulting in enhanced Th2 responses, perhaps via enhanced immune priming (54).

In conclusion, our findings suggest that virus-induced oxidative damage in vivo is the result of an imbalance between ROS production and airway antioxidant defenses. Based on our findings in this work as well as our previous published data in the experimental mouse model of RSV infection in which antioxidants were used (10), we suggest that modulation of AOE expression and/or blocking of oxidative stress response may represent potential pharmacological approaches to prevent or treat viral-induced lung inflammation and its long-term consequences.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Drs. Alan Buckpitt and Asa Wheelock, University of California Davis, for training in the lysis-lavage technique, and Mrs. Cynthia Tribble for her assistance in manuscript submission.

Supported by National Institutes of Health grants AI062885, AI30039, HV28184, UL1RR029876, by Department of Defense W81XWH1010146, and by Flight Attendant Medical Research Institute (FAMRI) Clinical Innovator Awards 072147 (A.C.) and 42253 (R.P.G.). P.D.J. and D.L.E. were supported by Postdoctoral Fellowships from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (T32–07254).

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue's table of contents at www.atsjournals.org

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1164/rccm.201010-1755OC on March 4, 2011

Author Disclosure: Y.M.H. does not have a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript. P.D.J. does not have a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript. D.L.E. does not have a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript. H.S. does not have a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript. A.K. does not have a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript. A.C. received grant support from the Department of Defense and the Flight Attendant Medical Research Institute. R.P.G. received grant support from the Department of Defense, the Flight Attendant Medical Research Institute, and NASA.

References

- 1.Nair H, Nokes DJ, Gessner BD, Dherani M, Madhi SA, Singleton RJ, O'Brien KL, Roca A, Wright PF, Bruce N, et al. Global burden of acute lower respiratory infections due to respiratory syncytial virus in young children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2010;375:1545–1555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leader S, Kohlhase K. Respiratory syncytial virus-coded pediatric hospitalizations, 1997 to 1999. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2002;21:629–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gabbita SP, Robinson KA, Stewart CA, Floyd RA, Hensley K. Redox regulatory mechanisms of cellular signal transduction. Arch Biochem Biophys 2000;376:1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Allen RG, Tresini M. Oxidative stress and gene regulation. Free Radic Biol Med 2000;28:463–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.MacNee W, Rahman I. Is oxidative stress central to the pathogenesis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease? Trends Mol Med 2001;7:55–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rahman I, Morrison D, Donaldson K, MacNee W. Systemic oxidative stress in asthma, COPD, and smokers. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1996;154:1055–1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hull J, Vervaart P, Grimwood K, Phelan P. Pulmonary oxidative stress response in young children with cystic fibrosis. Thorax 1997;52:557–560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Casola A, Burger N, Liu T, Jamaluddin M, Brasier AR, Garofal RP. Oxidant tone regulates RANTES gene transcription in airway epithelial cells infected with Respiratory Syncytial Virus: role in viral-induced Interferon Regulatory Factor activation. J Biol Chem 2001;276:19715–19722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu T, Castro S, Brasier AR, Jamaluddin M, Garofalo RP, Casola A. Reactive oxygen species mediate virus-induced STAT activation: role of tyrosine phosphatases. J Biol Chem 2004;279:2461–2469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Castro SM, Guerrero-Plata A, Suarez-Real G, Adegboyega PA, Colasurdo GN, Khan AM, Garofalo RP, Casola A. Antioxidant treatment ameliorates respiratory syncytial virus-induced disease and lung inflammation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006;174:1361–1369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hosakote YM, Liu T, Castro SM, Garofalo RP, Casola A. Respiratory syncytial virus induces oxidative stress by modulating antioxidant enzymes. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2009;41:348–357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jaiswal AK. Nrf2 signaling in coordinated activation of antioxidant gene expression. Free Radic Biol Med 2004;36:1199–1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hosakote, Y, Esham, D, Casola A, and Garofalo, RP. Oxidative injury in the lungs is associated with inhibition of antioxidant gene expression in RSV infection [abstract]. E-Pediatric Academic Societies 2010:2735.6. Available from: http://www.abstracts2view.com/pasall/view.php?nu=PAS10L1_2375.

- 14.Ueba O. Respiratory syncytial virus: I. concentration and purification of the infectious virus. Acta Med Okayama 1978;32:265–272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Patel JA, Kunimoto M, Sim TC, Garofalo R, Eliott T, Baron S, Ruuskanen O, Chonmaitree T, Ogra PL, Schmalstieg F. Interleukin-1 alpha mediates the enhanced expression of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 in pulmonary epithelial cells infected with respiratory syncytial virus. Am.J.Resp.Cell Mol. 1995;13:602–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guerrero-Plata A, Casola A, Garofalo RP. Human metapneumovirus induces a profile of lung cytokines distinct from that of respiratory syncytial virus. J Virol 2005;79:14992–14997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bohrer H, Qiu F, Zimmermann T, Zhang Y, Jllmer T, Mannel D, Bottiger BW, Stern DM, Waldherr R, Saeger HD, et al. Role of NFkB in the mortality of sepsis. J Clin Invest 1997;100:972–985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haeberle HA, Nesti F, Dieterich HJ, Gatalica Z, Garofalo RP. Perflubron reduces lung inflammation in respiratory syncytial virus infection by inhibiting chemokine expression and nuclear factor-kappaB Activation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002;165:1433–1438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wheelock AM, Zhang L, Tran MU, Morin D, Penn S, Buckpitt AR, Plopper CG. Isolation of rodent airway epithelial cell proteins facilitates in vivo proteomics studies of lung toxicity. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2004;286:L399–L410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Berndt P, Hobohm U, Langen H. Reliable automatic protein identification from matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometric peptide fingerprints. Electrophoresis 1999;20:3521–3526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang W, Chait BT. ProFound: an expert system for protein identification using mass spectrometric peptide mapping information. Anal Chem 2000;72:2482–2489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kahn JS. Human metapneumovirus: a newly emerging respiratory pathogen. Curr Opin Infect Dis 2003;16:255–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Magi B, Bini L, Perari MG, Fossi A, Sanchez JC, Hochstrasser D, Paesano S, Raggiaschi R, Santucci A, Pallini V, et al. Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid protein composition in patients with sarcoidosis and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a two-dimensional electrophoretic study. Electrophoresis 2002;23:3434–3444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rangasamy T, Cho CY, Thimmulappa RK, Zhen L, Srisuma SS, Kensler TW, Yamamoto M, Petrache I, Tuder RM, Biswal S. Genetic ablation of Nrf2 enhances susceptibility to cigarette smoke-induced emphysema in mice. J Clin Invest 2004;114:1248–1259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chan JY, Kwong M. Impaired expression of glutathione synthetic enzyme genes in mice with targeted deletion of the Nrf2 basic-leucine zipper protein. Biochim Biophys Acta 2000;1517:19–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Folkerts G, Kloek J, Muijsers RB, Nijkamp FP. Reactive nitrogen and oxygen species in airway inflammation. Eur J Pharmacol 2001;429:251–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ciencewicki J, Trivedi S, Kleeberger SR. Oxidants and the pathogenesis of lung diseases. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2008;122:456–468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schwarz KB. Oxidative stress during viral infection: a review. Free Radic Biol Med 1996;21:641–649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Indukuri H, Castro SM, Liao SM, Feeney LA, Dorsch M, Coyle AJ, Garofalo RP, Brasier AR, Casola A. Ikkepsilon regulates viral-induced interferon regulatory factor-3 activation via a redox-sensitive pathway. Virology 2006;353:155–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Haeberle H, Takizawa R, Casola A, Brasier AR, Dieterich H-J, van Rooijen N, Gatalica Z, Garofalo RP. Respiratory syncytial virus-induced activation of NF-kB in the lung involves alveolar macrophages and Toll-like receptor 4-dependent pathways. J Infect Dis 2002;186:1199–1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bao X, Sinha M, Liu T, Hong C, Luxon BA, Garofalo RP, Casola A. Identification of human metapneumovirus-induced gene networks in airway epithelial cells by microarray analysis. Virology 2008;374:114–127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kumar P, Khanna M, Srivastava V, Tyagi YK, Raj HG, Ravi K. Effect of quercetin supplementation on lung antioxidants after experimental influenza virus infection. Exp Lung Res 2005;31:449–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Akaike T, Noguchi Y, Ijiri S, Setoguchi K, Suga M, Zheng YM, Dietzschold B, Maeda H. Pathogenesis of influenza virus-induced pneumonia: involvement of both nitric oxide and oxygen radicals. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1996;93:2448–2453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Suliman HB, Ryan LK, Bishop L, Folz RJ. Prevention of influenza-induced lung injury in mice overexpressing extracellular superoxide dismutase. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2001;280:L69–L78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Biagioli MC, Kaul P, Singh I, Turner RB. The role of oxidative stress in rhinovirus induced elaboration of IL-8 by respiratory epithelial cells. Free Radic Biol Med 1999;26:454–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kaul P, Singh I, Turner RB. Effect of rhinovirus challenge on antioxidant enzemes in respiratory epithelial cells. Free Radic Res 2002;36:1085–1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Erzurum SC, Danel C, Gillissen A, Chu CS, Trapnell BC, Crystal RG. In vivo antioxidant gene expression in human airway epithelium of normal individuals exposed to 100% O2. J Appl Physiol 1993;75:1256–1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Boehme DS, Hotchkiss JA, Henderson RF. Glutathione and GSH-dependent enzymes in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid cells in response to ozone. Exp Mol Pathol 1992;56:37–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gilks CB, Price K, Wright JL, Churg A. Antioxidant gene expression in rat lung after exposure to cigarette smoke. Am J Pathol 1998;152:269–278. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Smith LJ, Shamsuddin M, Sporn PH, Denenberg M, Anderson J. Reduced superoxide dismutase in lung cells of patients with asthma. Free Radic Biol Med 1997;22:1301–1307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.De Raeve HR, Thunnissen FB, Kaneko FT, Guo FH, Lewis M, Kavuru MS, Secic M, Thomassen MJ, Erzurum SC. Decreased Cu,Zn-SOD activity in asthmatic airway epithelium: correction by inhaled corticosteroid in vivo. Am J Physiol 1997;272:L148–L154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ghosh S, Janocha AJ, Aronica MA, Swaidani S, Comhair SA, Xu W, Zheng L, Kaveti S, Kinter M, Hazen SL, et al. Nitrotyrosine proteome survey in asthma identifies oxidative mechanism of catalase inactivation. J Immunol 2006;176:5587–5597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tomaki M, Sugiura H, Koarai A, Komaki Y, Akita T, Matsumoto T, Nakanishi A, Ogawa H, Hattori T, Ichinose M. Decreased expression of antioxidant enzymes and increased expression of chemokines in COPD lung. Pulm Pharmacol Ther 2007;20:596–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Burns JS, Dockery DW, Neas LM, Schwartz J, Coull BA, Raizenne M, Speizer FE. Low dietary nutrient intakes and respiratory health in adolescents. Chest 2007;132:238–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chung-man HJ, Zheng S, Comhair SA, Farver C, Erzurum SC. Differential expression of manganese superoxide dismutase and catalase in lung cancer. Cancer Res 2001;61:8578–8585. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kensler TW, Wakabayashi N, Biswal S. Cell survival responses to environmental stresses via the Keap1-Nrf2-ARE pathway. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 2007;47:89–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kaspar JW, Niture SK, Jaiswal AK. Nrf2:INrf2 (Keap1) signaling in oxidative stress. Free Radic Biol Med 2009;47:1304–1309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cho HY, Imani F, Miller-Degraff L, Walters D, Melendi GA, Yamamoto M, Polack FP, Kleeberger SR. Antiviral activity of Nrf2 in a murine model of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2009;179:138–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Suzuki M, Betsuyaku T, Ito Y, Nagai K, Nasuhara Y, Kaga K, Kondo S, Nishimura M. Down-regulated NF-E2-related factor 2 in pulmonary macrophages of aged smokers and patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2008;39:673–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hua CC, Chang LC, Tseng JC, Chu CM, Liu YC, Shieh WB. Functional haplotypes in the promoter region of transcription factor Nrf2 in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Dis Markers 2010;28:185–193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Marzec JM, Christie JD, Reddy SP, Jedlicka AE, Vuong H, Lanken PN, Aplenc R, Yamamoto T, Yamamoto M, Cho HY, et al. Functional polymorphisms in the transcription factor NRF2 in humans increase the risk of acute lung injury. FASEB J 2007;21:2237–2246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Garofalo RP, Patti J, Hintz KA, Hill V, Ogra PL, Welliver RC. Macrophage inflammatory protein 1-alpha, and not T-helper type 2 cytokines, is associated with severe forms of bronchiolitis. J Infect Dis 2001;184:393–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Davis JM, Auten RL. Maturation of the antioxidant system and the effects on preterm birth. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med 2010;15:191–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Moghaddam A, Olszewska W, Wang B, Tregoning JS, Helson R, Sattentau QJ, Openshaw PJ. A potential molecular mechanism for hypersensitivity caused by formalin-inactivated vaccines. Nat Med 2006;12:905–907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.