Abstract

Motivation: Early and accurate detection of human pathogen infection is critical for treatment and therapeutics. Here we describe pathogen identification using short RNA subtraction and assembly (SRSA), a detection method that overcomes the requirement of prior knowledge and culturing of pathogens, by using degraded small RNA and deep sequencing technology. We prove our approach's efficiency through identification of a combined viral and bacterial infection in human cells.

Contact: nshomron@post.tau.ac.il

1 INTRODUCTION

Early and accurate detection of microbial pathogens in both clinical and environmental samples is critical for effective public health care, treatment and therapeutics. Most pathogen detection methods [polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification or microarrays] rely on prior knowledge of the exact sequence of the potential pathogen, or the ability to cultivate the pathogen (for microbial cultures), which is unreasonable in many cases (Douglas, 2005; Straub et al., 2005). An alternative detection technique recently offered, which circumvents these limitations, is the sequencing of infected cells and the subsequent comparison of these sequences to a reference pathogen library for identification (MacConaill et al., 2008). Given the massive increase in nucleic acid sequence databases of all organisms, and the advancement in massive parallel sequencing technologies, sequencing possibly infected samples evolves as an increasingly prominent and logical alternative for pathogen characterization. The major advantages of this approach are the unbiased detection of all known pathogens, overcoming the requirement for cultivation of slow-growing and fastidious microbial agents; the ability to recognize pathogens, even at minute expression levels; simultaneous identification of several microbial agents in a co-infected sample; and the rapid turnaround and processing.

2 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Here we introduce a novel approach for pathogen detection using short reads, generated by deep sequencing of short RNA extracts. This three step approach includes: (i) alignment of the short reads against the human reference genome; (ii) subtraction and assembly of the remaining unmapped reads; and (iii) categorization and identification of the pathogen infection, based on nucleic acid databases. We term our approach short RNA subtraction and assembly (SRSA). We applied our method to Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) infected cells, precisely identifying the infected cells and the infecting agents.

In order to identify minute quantities of non-host organisms, we chose to analyze RNA in sizes that maximize the pathogen-to-host nucleotide ratio. Utilizing small RNA (20–50 nt) for pathogen detection, rather than the currently used cDNA and ESTs (Weber et al., 2002), has several apparent advantages. Specific short RNA extracts provide a larger pathogen-to-host ratio than DNA samples since host DNA is usually several orders of magnitude larger than pathogen DNA/RNA, and thus much more abundant in the sample. An increased non-host RNA quantity is achieved due to a higher RNA degradation rate in bacteria (Rauhut et al., 1999) and the presence of fragmented viral sequences (due to RNA interference) (Obbard et al., 2009) leading to prevalent bacterial and viral RNA at lower molecular weights. Unambiguous mapping of short RNAs to the human genome is preferred to circumvent splicing events of longer transcripts, since the proportion of reads spanning splice junctions is minute. This also increases our confidence in the unmapped reads being derived from non-human origin. Finally, short RNA extraction excludes the highly abundant host RNA species (e.g rRNA and tRNA) that can potentially over-cloud non-short RNA experiments.

All infected tissue contains nucleic acids from both the host and the infecting agent. It has been shown that mapping long sequence reads from a transcript sample against the human genome and analyzing the non-human reads has the potential of identifying non-human pathogen genes (Xu et al., 2003). These transcript subtraction methods utilize thousands of long sequence reads (>200 nt), produced by standard Sanger sequencing or Roche 454 sequencer. They were not, however, applied on reads shorter than 200 nt, like the ones produced by currently more common sequencing platforms, such as the Illumina Genome Analyzer or HiSeq 2000, that produce millions of short reads (<100 nt) in a single run (Voelkerding et al., 2009).

Methods utilizing short RNA sequencing and assembly were previously applied mainly for viral detection and classification in plants and invertebrates. Kreuze et al. (2009) sequenced and assembled viral small RNA in sweet potato without the need for subtraction of the host-derived sequences. However, this method would not suit mammalian samples, as skipping the subtraction step could result in excess of, or over-clouding by, host-derived reads (>90%). Briese et al. (2009) selected larger RNA products (>70 bp) from clinical samples taken from human serum and tissue and, following assembly, they were able to detect and classify a new strain of infecting Arenavirus. However, the majority of their viral sequences were obtained from the serum sample, where competing cellular abundant RNA species are absent. This approach would likely reduce the pathogen-to-host-ratio in non-serum samples and as a consequence limit detection sensitivity. Wu et al. (2010) applied an approach termed ‘vdSAR’ to assemble previously sequenced small RNA libraries from invertebrates, in order to both demonstrate their sequence overlap, and to classify the infecting viral agents. However, dealing with mammalian genomes and a large number of sequencing reads (>10 million) necessitates a host-based sequence subtraction step for increasing accuracy. Thus, our approach is unique, as we utilize short RNA subtraction and assembly in mammalian-derived cells, to maximize pathogen-to-host-ratio; demonstrate recognition of both viral and bacterial infecting agents; and suggest a possible siRNA-related immune response.

Short sequence reads present a confounding problem of multiple organisms' alignment (Trapnell et al., 2009a) and thus inconclusive identification of the organisms. In order to identify the non-human sequences and target to which organism it aligns, we applied de novo sequencing (sequence assembly), using an assembly software [Velvet (Zerbino et al., 2008)] to produce longer consensus sequences from our given short read sample. These longer assembled reads were then compared to known organisms' references [using BLAST (Dumontier et al., 2002)] to produce high scoring unique alignments and thus a valid and conclusive identification, which could not have been reached otherwise.

We used cell line infected with Human Immunodeficiency Virus 1 (HIV-1; see Section 2). Using an alignment software [Burrows-Wheeler Aligner (BWA) (Li and Durbin, 2009)], we aligned the reads produced by our sequencing platform against the human reference genome. Our sequencing produced >10 million reads for each sample, with an average read length of 34 nt. Filtering the human genome-associated reads produced 6% and 17% unmapped reads in the HIV-1 negative and positive samples, respectively.

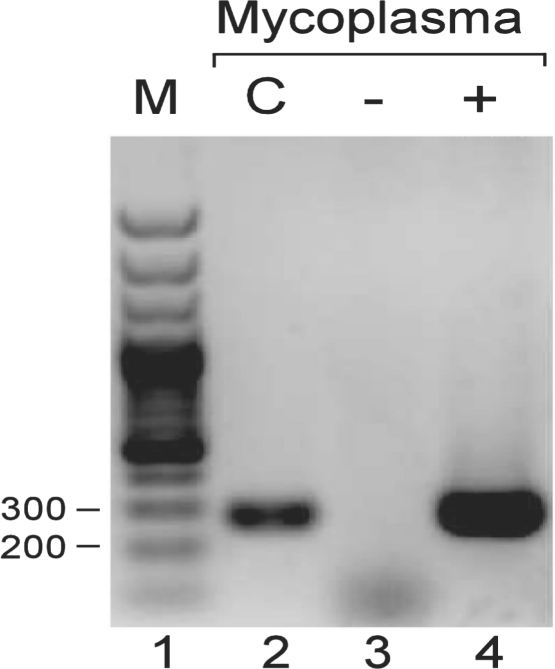

In order to reduce the number of multiple organism hits we expect when matching such short reads against a large database, we assembled each read groups into longer contigs. The assembly process produced 16 and 878 contigs, with an average length of 75 and 91 nt for the HIV-1 negative and positive samples, respectively. As we expected, the assembly process was far more productive in the HIV-1 positive sample than the negative one, due to the presence of more specific non-human organisms' sequences. We then used NCBI's megablast to match these contigs against any known organism. Megablast was chosen since it is an optimal tool for identical sequence detection for both short and long sequences. Since our goal was not to find homologous sequences but rather to detect the most probable and specific sequence in the nucleotide database, megablast was preferred over other optional tools. Using an in-house specific software (available upon request), we incorporated only the highest scoring hits in the downstream analysis, and filtered out non-unique organism hits, meaning that any contig that matched more than one organism was discarded. We also set the combined E-value of all unique hits to be 1*E−200 at most (See Section 2 for more detail). After applying these filters to the Blastn results, we could not identify any non-human organism in the HIV-1 negative sample. In the HIV-1 positive sample, however, we identified two non-human organisms: HIV-1 and Mycoplasma Hyorhinis HUB-1 (Table 1). We then further analyzed the distribution of hits matching any HIV strain, finding the strain accumulating the highest number of hits was, in fact, the exact strain used to infect the sample (HIV-HXB2; Table 2). To confirm the detection of Mycoplasma in our HIV-1-infected sample, we used a standard Mycoplasma test kit (Fig. 1), followed by a PCR and a sequencing confirmation that verified the Mycoplasma strain was indeed of the Hyorhinis strain. The detection of Mycoplasma and HIV-1 validates the accuracy and sensitivity of our method in identifying both intracellular viral agents and environmental bacterial contaminants, in the same given sample.

Table 1.

Identified pathogens in our samples using SRSA method

| Organism | Unique | Multiple | Total | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| hits | hits | E-value | score | |

| Mycoplasma Hyorhinis HUB-1 | 564 | 51 | 0 | 48 951 |

| Mycoplasma Hyorhinis | 12 | 42 | 0 | 1544 |

| Human immunodeficiency virus 1 | 13 | 26 | 0 | 1138 |

Unique hits, describes the number of queries that matched only one specific organism. Multiple hits, describes the number of queries in which the organism was one of the organisms matched. Total E-value, the combined E-value of all unique organism hits. Total score, describes the sum of all scores for each organism query hit, with reduced weight for multiple organisms hits score.

Table 2.

Distribution of HIV related BLAST hits

| HIV hit name | Total hits |

|---|---|

| HIVHXB2CG HIV type 1 (HXB2), complete genome; HIV1/HTLV-III/LAV reference genome | 1.147 |

| HIV-1, complete genome | 0.809 |

| Human T-cell leukaemia type III (HTLV-III) proviral genome | 0.475 |

| HIVBH102 HIV type 1, isolate BH10, genome | 0.475 |

| HIVPV22 HIV type 1, isolate PV22, complete genome (H9/HTLV-III proviral DNA) | 0.454 |

| HIVTH475A HIV type 1 (individual isolate: TH4-7-5) gene | 0.333 |

| HIV-1 isolate F233 from Argentina vpu gene, complete sequence | 0.333 |

| HIVH3BH5 HIV type 1, isolate BH5 | 0.316 |

| HIV-1 proviral vif gene DNA | 0.294 |

| HIVMCK1 HIV 1 DNA | 0.275 |

The distribution of blast HIV-related hits, after the multiple hit adjustments in which one of the hits for a query matching n number of organism is added 1/n to its total hits. This adjustment was utilized in intraspecies strain differentiation and was able to single out HXB2 as the strain of HIV in our sample.

Fig. 1.

PCR products visualized in 1.5% agarose gel, a single band for both SupT1 + HIV-1 sample (lane 4) and the positive control (c) from the mycoplasma detection kit (lane 2) observed within the predicted marker (m) size range (270 bp). Lane 3 is the uninfected cells.

In addition to the efficient detection of HIV in our sample, sequencing data coverage analysis showed that when mapping our human-alignment unmapped reads against HIV reference genome, 87% of the bases were covered with an average coverage of 18 reads. This comprehensive read depth could be utilized for further phylogenetic, strain and mutation analysis, relevant in microbial detection and research (Wang et al., 2007).

Due to the decrease in cost and increase in efficiency of deep sequencing platforms, we expect sequencing utilization in the field of pathogen detection and identification to increase. Our method, based on using small RNA, to increase the pathogen-to-host ratio, proves to be a useful tool for microbial identification and detection. Our computational approach of subtraction and assembly (SRSA) presents an easily implemented pipeline, appropriate for all types of current sequencing platforms. We envision early and accurate detection of pathogen infection, using short RNA reads to accelerate clinical biomedical investigation.

3 METHODS

3.1 Sample preparation

SupT1 cells (human, Caucasian, pleural effusion, lymphoma, T cell) were infected with HIV-1 (HXB2 strain) on day 0. Four days post-infection, ~50% of naive cells were added to the cultures, and 4 days later they were harvested. Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen), and 10 μg of each sample were prepared for deep sequencing following Illumina's small RNA sample preparation protocol v1. Briefly, samples were ligated with 3′ and 5′ adapters, reverse transcribed and then PCR amplified. cDNA library was prepared from 93 to 100 bp PCR products, and sequenced in separate lanes on an Illumina Genome Analyzer IIx instrument at the Tel Aviv University Genome High-Throughput Sequencing Laboratory.

3.2 Alignment and assembly

The sequenced reads were clipped for the standard short RNA adapter, using fastx clipper (http://hannonlab.cshl.edu/fastx_toolkit/), discarding all reads <16 nt. Our sequencing method produced 21 048 677 and 12 003 830 reads after clipping for HIV-1 negative and positive samples, respectively. We then aligned the reads using BWA alignment software (using the default parameters) against the human genome (hg19) reference, retrieved from NCBI. We re-aligned our positive sample using TopHat (Trapnell et al., 2009b), which considers splice junctions in the alignment process, to test the confounding effect of splice junctions presence on our results. Since BWA demonstrated higher mapping accuracy (83% as opposed to 78% using TopHat), all downstream analysis was conducted on its output. Filtering the human genome-associated reads produced 1 251 267 (6%) and 1 992 557 (16.6%) unmapped reads in the HIV-1 negative and positive samples, respectively. The unmapped reads were then assembled, using Velvet's AssemblyAssembler (v1.3), which conducts assemblies with predefined parameter values across a user-specified range of k-mer values, followed by utilization of the contigs from all previous assemblies, as input for a final assembly. We ran the script with a wide range of hash lengths of 9–31 nt in order to optimize the length of the contigs. The most effective length was found to be within the range of 17 to 25 nt. The assembly produced 16 and 878 contigs with an average length of 75 and 91 nt for the HIV-1 negative and positive samples, respectively. The difference in the amount of produced reads can be accounted for by the lack of non-human-associated sequences in the negative sample.

3.3 Categorization and identification

The assembled contigs were then aligned, using NCBI's nucleotide megablast with a word size of 28, against the ‘All non-redundant GenBank CDS translations+PDB+SwissProt+PIR+PRF’ database, with an inclusion threshold E-value of 0.01. Using an in-house developed software (available upon request), we included only the highest ranking hits (with lowest E-value and highest total score) per query for the downstream analysis. Using the blast results, we produced an organism table for each sample. Unique organism hits were added, when all the highest ranking included hits per query matched only a single organism [organism taxonomy retrieved using NCBI's E-utils (http://eutils.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) and taxonomy database]. Multiple hits were counted for each organism matched per query. The organism's total E-value was calculated by multiplying the E-value of all the unique hits (E-value is nearly identical to P-values for E<0.01). To account for the multiple hits in the blast results, we also calculated an organism total score, by summing the score for each unique organism hit with the score for each multiple hit, divided by the number of different organisms per query. This summation approach did not increase our interspecies differentiation capabilities, since different species could have a different number of strains and annotations. It was, however, utilized in our intraspecies analysis, prioritizing the different strains (Table 2). Deciding on a standard of maximum total E-value of 1*E−200, no organism was identified in the HIV-1 negative sample, the most prominent was Homo sapiens with nine unique hits. In the HIV-1 positive sample, four organisms were identified, one of which was Homo sapiens, the other three were Mycoplasma Hyorhinis HUB-1, Human Immunodeficiency Virus 1 and Mycoplasma Hyorhinis. While optimizing our method, we found that its sensitivity was very high, detecting both infecting agents and host-related sequences with very high certainty, and an extremely low E=0. We also observed that the number of different taxonomies passing the basic filter of having the highest query score and lowest E-value was very high, demonstrating a low specificity rate. Out of 385 different taxonomies passing the basic filter, 14 were Mycoplasma out of which 3 were of the Hyorhinis strain. There were also 19 different human immunodeficiency virus taxonomies and 1 Homo sapiens. Counting only the Hyorhinis, HIV-1 and Homo sapiens as true positives (true positive rate; TPR=0.06), our method demonstrated a false positive rate (FPR) of 0.94. We then sought to implement more rigorous inclusion criteria to reduce the FPR, while maintaining high sensitivity. Setting our inclusion criteria to only include taxonomies that have unique query hits, resulted in eight different taxonomies, one of which is Homo sapiens, one HIV-1 and four Mycoplasma out of which two are Hyorhinis reaching an FPR of 0.5. We then added a maximal E-value threshold equal to 1*E−200, which resulted in only four taxonomies remaining, all of which are true positives, with Mycoplasma Arginini being the closest taxonomy for inclusion with 4*E−181. We also noticed that the total score, calculated by dividing each query score against the number of taxonomies it hits and summing it for each taxonomy, could also serve as a reliable filtration standard, though further tests are required.

3.4 Mycoplasma confirmation

To confirm the detection of a Mycoplasma contamination in our HIV-1-infected sample, we used EZ-PCR Mycoplasma test kit (Biological Industries, Beit-Ha'Emek) on the samples (50 ng in 50 μl reaction volume) following High-Capacity Reverse Transcription Kit with random primers (Applied Biosystems) (1 μg RNA in 15 μl total reaction volume). The products were separated in Agarose gel (Fig. 1), and bands were excised from the gel using Wizard SV Gel Clean-Up System (Promega). Confirmation sequencing was done using the forward primer 5′-GGGAGCAAACAGGATTAGATACCCT-3′. This confirmation strengthens our methods' fidelity, since Mycoplasma is indeed present in the sample.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Tel Aviv University Genome High-Throughput Sequencing Laboratory staff, Drs Varda Oron-Karni, Orly Yaron and Nitzan Kol, for their dedicated and professional work. We thank Judit Kovarsky for assisting and advising in the assembly process and David Golan in the statistics. We thank Prof. Zvi Bentwich and Drs Eran Bacharach and Eran Halperin for helpful discussions. We thank Dana Braff for commenting on the manuscript. This work was performed in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a PhD degree of O.I. and S.M. at the Sackler Faculty of Medicine, Tel Aviv University.

Funding: The Shomron laboratory is supported by the Chief Scientist Office, Ministry of Health, Israel; Kunz-Lion Foundation; Ori Levi Foundation for Mitochondrial Research; Israel Cancer Association; the Wolfson family Charitable Fund. O.I. is supported by a fellowship from the Edmond J. Safra Bioinformatics program at Tel-Aviv University.

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- Briese T., et al. Genetic detection and characterization of Lujo virus, a new hemorrhagic fever–associated Arenavirus from Southern Africa. PLoS Pathogens. 2009;5:e1000455. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas R. Challenges and opportunities for pathogen detection using DNA microarrays. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2005;31:91–99. doi: 10.1080/10408410590921736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumontier M., Hogue C.W. NBLAST: a cluster variant of BLAST for NxN comparisons. BMC Bioinformatics. 2002;3:13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-3-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreuze J.F., et al. Complete viral genome sequence and discovery of novel viruses by deep sequencing of small RNAs: a generic method for diagnosis, discovery and sequencing of viruses. Virology. 2009;388:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2009.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H., Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;26:589–595. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacConaill L., Meyerson M. Adding pathogens by genomic subtraction. Nat. Genet. 2008;40:380–382. doi: 10.1038/ng0408-380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obbard D.J., et al. The evolution of RNAi as a defence against viruses and transposable elements. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2009;364:99–115. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2008.0168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauhut R., Klug G. mRNA degradation in bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 1999;23:353–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.1999.tb00404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straub T.M., et al. Automated methods for multiplexed pathogen detection. J. Microbiol. Methods. 2005;62:303–316. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2005.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trapnell C., Salzberg S.L. How to map billions of short reads onto genomes. Nat. Biotechnol. 2009a;27:455–457. doi: 10.1038/nbt0509-455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trapnell C., et al. TopHat: discovering splice junctions with RNA-Seq. Bioinformatics. 2009b;25:1105–1111. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voelkerding K.V., et al. Next-generation sequencing: from basic research to diagnostics. Clin. Chem. 2009;55:641–658. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2008.112789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C., et al. Characterization of mutation spectra with ultra-deep pyrosequencing: application to HIV-1 drug resistance. Genome Res. 2007;17:1195–1201. doi: 10.1101/gr.6468307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber G., et al. Identification of foreign gene sequences by transcript filtering against the human genome. Nat. Genet. 2002;30:141–142. doi: 10.1038/ng818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Q., et al. Virus discovery by deep sequencing and assembly of virus-derived small silencing RNAs. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:1606–1611. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911353107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y., et al. Pathogen discovery from human tissue by sequence-based computational subtraction. Genomics. 2003;81:329–335. doi: 10.1016/s0888-7543(02)00043-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zerbino D.R., Birney E. Velvet: algorithms for de novo short read assembly using de Bruijn graphs. Genome Res. 2008;18:821–829. doi: 10.1101/gr.074492.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]