Abstract

The hedgehog signaling pathway plays an important role in cell growth and differentiation both in normal embryonic development and in tumors. Our previous work shows that hedgehog pathway is frequently activated in esophageal cancers. To further elucidate the role of hedgehog pathway in esophageal cancers we examined the expression of the target genes, hedgehog-interacting protein (HIP) and platelet derived growth factor receptor alpha (PDGFRα) and hedgehog signaling molecules, smoothened (SMO), suppressor of fused (Su(Fu)) in the specimens using in situ hybridization and RT-PCR. We found that HIP, PDGFRα, SMO and Su(Fu) gene highly expressed in the primary esophageal squamous cell carcinomas but not in normal esophageal tissue. The transcripts of HIP, PDGFRα and SMO were expressed in 13 of 15 esophageal cancers. Su(Fu) expression was missing in 2 esophageal cancers. The results from in-situ hybridization were further confirmed by RT-PCR. Our results revealed a set of genes for detecting hedgehog signaling activation in esophageal cancer.

Keywords: esophageal cancer, hedgehog, hedgehog-interacting protein, platelet derived growth factor receptor alpha, smoothened, suppressor of fused

Introduction

Hedgehog (HH) signaling pathway regulates many processes in development, homeostasis in tissues, and ectopic expression of HH signaling pathway components are responsible for tumorigenesis. In the absence of HH, PTCH1 prevents SMO from signaling. When HH binds to PTCH1, SMO is free to pass signal to transcriptional factor GLIs and activate the target genes (e.g. PTCH1, GLI1, HIP and PDGFRα).

Active Smoothened contribute to activating the signaling pathway, result in inappropriate transcription of target genes, which may be important in the pathogenesis of carcinomas. Activated Smoothened mutations have been found in sporadic basal-cell carcinomas [1,2], over expression of smoothened was found in several tumors [3–5]. HIP is the target gene of HH pathway also is a negative hedgehog signaling regulator by binding to the hedgehog protein. Silence of HIP was found in several cancer cell lines as well as tumors through genetic and/or epigenetic alternations [6–8]. Su(Fu) is an essential repressor in mammalian hedgehog signaling [9]. Mice with both heterozygous PTCH1 and Su(fu) had higher to develop tumor [10]. Mutations in Su(Fu) or loss of Su(Fu) expression was reported in cancer cell lines and tumors [11–14]. Expression of PDGFRα was found in several types of tumors [15–18], and involved in tumor cell growth and metastasis [19–22].

Esophageal cancer is one of the most frequent cancers and with high mortality rates in the world. We have demonstrated the over-expression of Sonic hedgehog (SHH) and its target genes, GLI1 and PTCH1 (patched1) in the tissues of esophageal primary tumors both on mRNA and protein levels. And SMO antagonist or the SHH antibodies treated esophageal cancer cells are inhibited growth and induced apoptosis [23]. But there is short of expression of other genes of this signaling pathway in esophageal primary cancers. To identify if there are activation of other components in this pathway we analyze the expression of HIP, PDGFRα, SMO and Su(Fu) by using in situ hybridization and RT-PCR.

Material and methods

Tumor sample

Specimens from 15 cases of esophageal cancers were received as discarded materials from the Shangdong QiLu Hospital, Jinan, China as our previous report [23]. Pathology reports and H&E staining of each specimen were reviewed to determine the nature of the disease and the tumor histology. Esophageal cancers were identified according to the WHO guideline [24] as squamous cell carcinomas (15 cases) (Table 1). Five specimens of normal esophageal tissues were obtained from five esophageal cancer patients hospitalized in Shandong Provincial Hospital as discarded materials (Table 1).

Table 1.

Esophageal cancer specimens and summary of SHH, PTCH1, GLI1, SMO, Su(Fu), HIP and PDGFRα expression from in situ hybridization

| No | Age | Sex | Pathology diagnosis | Stage | *SHH/PTC H1/GLI1 | SMO | HIP | PDGFRα | Su(Fu) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 57 | F | Squamous cell carcinoma (W) | III | − | ± | + | + | + |

| 2 | 57 | M | Squamous cell carcinoma (W) | II | + | + | ± | + | + |

| 3 | 65 | M | Squamous cell carcinoma (W) | II | + | + | ± | ± | + |

| 4 | 54 | M | Squamous cell carcinoma (W) | II | + | ± | ± | ± | + |

| 5 | 51 | M | Squamous cell carcinoma (W) | II | + | ± | ± | + | + |

| 6 | 56 | F | Squamous cell carcinoma (M) | III | + | + | ± | + | N/A |

| 7 | 64 | M | Squamous cell carcinoma (M) | II | − | ± | ± | + | + |

| 8 | 52 | M | Squamous cell carcinoma (M) | III | + | ± | ± | ± | − |

| 9 | 47 | F | Squamous cell carcinoma (M) | II | − | − | − | − | − |

| 10 | 64 | F | Squamous cell carcinoma (P) | II | + | + | ± | + | N/A |

| 11 | 54 | M | Squamous cell carcinoma (P) | III | + | + | ± | + | N/A |

| 12 | 73 | M | Squamous cell carcinoma (P) | II | + | − | − | − | − |

| 13 | 38 | F | Squamous cell carcinoma (P) | III | + | + | + | + | N/A |

| 14 | 55 | M | Squamous cell carcinoma (P) | II | − | ± | ± | ± | − |

| 15 | 45 | M | Squamous cell carcinoma (P) | III | + | + | ± | ± | + |

| 16 | 60 | M | Normal | N/A | − | − | − | − | |

| 17 | 58 | M | Normal | N/A | − | − | − | − | |

| 18 | 57 | F | Normal | N/A | − | − | − | − | |

| 19 | 64 | M | Normal | N/A | − | − | − | − | |

| 20 | 64 | M | Normal | N/A | − | − | − | − |

The results of SHH, PTCH1 and GLI1 in-situ hybridization were from our previous study.

W: well, M: moderate, P: poor.

In situ hybridization

Tissue sections (6 μm thick) were mounted onto poly-L-lysine slides. Following deparaffinization, tissue sections were rehydrated in a series of dilutions of ethanol. To enhance signal and facilitate probe penetration, sections were immersed in 0.3% Triton X-100 solution for 15 min at room temperature, followed by treatment with proteinase K (20 μg/ml) for 20 min at 37 ºC. The sections were then incubated with 4% (v/v) paraformaldehyde/PBS for 5 min at 4 ºC. After washing with PBS and 0.1M triethanolamine, the slides were incubated with prehybridization solution (50% formamide, 50% 4×standard saline citrate) for 2 hr at 37 ºC. The probe was added to each tissue section at a concentration of 1μg/ml and hybridized overnight at 42 ºC. After high-stringency washing (2×SSC twice, 1×SSC twice, 0.5×SSC twice at 37 ºC), sections were incubated with an alkaline phosphatase-conjugated sheep antidigoxigenin antibody, which catalyzed a color reaction with the NBT/BCIP (nitro-blue-tetrazolium/ 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate) substrate (Roche). Blue indicated strong hybridization. As negative controls, sense probes were used in all hybridization and no positive signals were observed.

RT-PCR

Total RNAs were extracted using a RNA extraction kit from Promega according to the manufacturer (Promega, Madison, WI). PCR was performed using 10 pmol each of primers in a standard 50 ml PCR reaction containing 100 mM dNTPs and cDNA from human tissue cDNA expression libraries as template. The primer sequences are shown in (Table 2). DNA was amplified by Taq DNA Polymerase for 30 cycles, and then was run on a 0.8% agarose gel mixed with ethidium bromide. The bands were visualized under UV light before taking pictures.

Table 2.

Primers used in RT-PCR.

| Gene name | Primers |

|---|---|

| SMO | F: AAGGCCACGCTGCTCATCTGG |

| R: CATTGAGGTCAAAGGCCAAGC | |

| Su(Fu) | F: AGAGTGCCGCCGCCTTTACC |

| R: ACGGGCTGCATCTGTGGGTC | |

| HIP | F: TTCCATACCAAGGAGCAACC |

| R: TCTTGCCACTGCTTTGTCAC | |

| PGDFRα | F: GCTTTCATTACCCTCTATCCT |

| R: GAATCATCCTCCACGA |

Results

Expression of HIP and PDGFRα in esophageal cancers

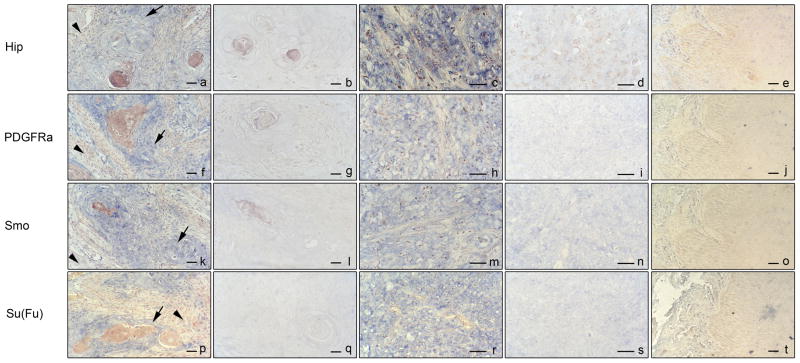

Several putative HH target genes have been discovered, but only a few of them have been confirmed in esophageal cancer[23]. Several studies indicate that elevated expression of HIP indicates HH signaling activation in human cancer [11,25]. PDGFRα expression was elevated in basal cell carcinomas, in which HH pathway was activated[26]. To assess expression of HIP and PDGFRα in esophageal cancers, we examined expression of HIP and PDGFRα in 15 cases of esophageal specimens and 5 normal esophageal tissues using in situ hybridization. We found that 13 of the 15 (86.7%) tumor specimens expressed HIP and PDGFRα transcripts (see Table 1 for details). Most of the expression was detected in the tumor tissues (blue in Figure.1a, f, indicated by arrows), not in the stroma (Figure.1a, f, indicated by arrow heads). The anti-sense probe showed good signal (Figure.1a, c, f, h) while the sense probe did not yield any staining (Figure.1b, d, g, i), indicating specificity of in-situ hybridization. Positive staining of HIP and PDGFRα did not show in normal tissue (Figure.1e, j). Further analysis showed that HIP and PDGFRα co-expressed in all the 13 tissues, and there is consistency of expression of PTCH1, Gli1, HIP and PDGFRα in 11 of 15 esophageal cancers (Table 1, data obtained from our previous publication[23]), indicating that detection of HIP and PDGFRα is as effective as detection of Gli1 or PTCH1 in esophageal cancer. The result was confirmed by RT-PCR (data not show). Taken together, we found that transcripts of HIP and PDGFRα were highly expressed in esophageal cancer specimens which contained activation of hedgehog pathway.

Figure 1.

Expression of HIP, PDGFRα, SMO and Su(Fu) in esophageal tumors. HIP, PDGFRα, SMO and Su(Fu) transcript (blue as positive, indicated by arrows) was detected by in situ hybridization in normal esophageal tissue (e, j, o, t), well-differentiated Squamous Cell Carcinoma (a, f, k, p) and poorly-differentiated Squamous Cell Carcinoma (c, h, m, r), b, d, g, i, l, n, q and s are their controls with respective sense probe. Bar presents 200μm.

Expression of SMO and Su(Fu) in esophageal cancers

In addition to HH target genes, we also investigated expression of hedgehog signaling molecules in gastric cancer. We examined expression of SMO in 15 cases and Su(Fu) in 11 cases of esophageal specimens and 5 normal esophageal tissues using in situ hybridization. Expressing of SMO was found in 13 of the 15 (86.7%) tumor specimens and Su(Fu) was expressed in 7 of the 11 (63.6%) tumor tissues (see Table 1 for details). Most of the signal (Blue as indicated by arrows in Figure.1k, p) was detected in the tumor tissue, not in the stroma (as indicated by arrow heads in Figure.1k, p). Since the sense probe of SMO and Su(Fu) did not give any signals, we believe our in-situ hybridization method is very reliable. SMO was co-expressed with HIP and PDGFRα in 13 esophageal cancers. Two cases with expression of SMO, HIP and PDGFRα transcripts lost expression of Su(Fu), indicating that silence of Su(Fu) may responsible for HH pathway activating in these two tumors. We did not detect the positive staining of SMO and Su(Fu) in normal tissues (Figure.1o, t). We performed RT-PCR to confirm the result of in-situ hybridization (data not show). Taken together, we found elevated expression SMO and Su(Fu) in esophageal cancer which contained activation of hedgehog pathway and there were two specimens showed lost expression of Su(Fu).

Discussion

It is important to identify activity of hedgehog pathway in cancers to improve diagnosis and treatment. However, previous studies only detected a few target genes of hedgehog pathway. To better understand expression profile of hedgehog pathway in cancer, we investigate expression of HIP, PDGFRα, SMO and Su(Fu) in esophageal cancer. Our result showed that HIP and PDGFRα highly expressed in esophageal cancer, which is consistent with expression of PTCH1 and Gli1 (Table 1). Our results indicate that HIP and PDGFRα is effective as PTCH1 and Gli1 in identification of activation of hedgehog pathway, which is different from the study we perform in gastric cancer [30]. We found that transcripts of HIP, Gli1 and PTCH1 are highly expressed in gastric cancer specimens whereas the PDGFRα transcript is detectable only in a subset of cancer with expression of Gli1, PTCH1 and HIP. Further more, the study shows that Gli1 can activate PDGFRα in C3H10T1/2 cells[26]. Various expression of PDGFRα in esophageal and gastric cancer suggests that hedgehog pathway functions though different molecule in different type or subtype of cancers. Therefore, identification of mechanism by which PDGFRα is regulated will enrich our understanding in hedgehog-mediate carcinogenesis. Currently, STI571 is used in clinical therapeutics against PDGFRα function[27]. It may shed the light that esophageal cancer with detectable expression of PDGFRα may be eligible for treatment with STI571.

It is reported that transcriptional silencing of HIP protein is found in cancer cell lines and cancer tissues [7]. Our studies did not reveal any reduced expression of HIP in tumors with detectable expression of Gli1 and PTCH1, suggesting that silencing of HIP in esophageal cancer is not a major mechanism for HH signaling activation. There are several reports indicating that alterations of HH signaling molecules may be responsible for Hh signaling activation. Su(Fu) is an essential repressor in mammalian hedgehog signaling [9], inhibiting the function of GLI molecules through several mechanisms [28]. Mutations in Su(Fu) have been found in cancer cell lines and tumors [11,13,14]. However, we did not find significant alteration in the expression of Su(Fu) in esophageal cancer, suggesting that Su(Fu) inactivation is not very common in esophageal cancer. SMO expression is elevated in a subset of prostate cancer specimens [29]. Our data showed SMO highly expressed in esophageal cancer and expression of SMO was consistent with expression of HIP and PDGFRα. Whether the SMO transcript level can be used to detect HH signaling activation in other subtypes of esophageal cancer remains to be determined.

Our study found that HIP, PDGFRα, SMO and Su(Fu) gene are highly expressed in the primary esophageal squamous cell carcinomas. The transcripts of HIP, PDGFRα and SMO were expressed in 13 of 15 esophageal cancers. Su(Fu) expression was missing in 2 esophageal cancer specimens. The results indicate that activation of the hedgehog pathway occurs frequently in esophageal cancers. Our results revealed a set of genes for detecting Hh signaling activation in esophageal cancer.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (30671072 and 30570967) and the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (2007CB947100 and 2007CB815800).

References

- 1.Xie J, Murone M, Luoh SM, Ryan A, Gu Q, Zhang C, Bonifas JM, Lam CW, Hynes M, Goddard A, Rosenthal A, Epstein EH, Jr, de Sauvage FJ. Activating Smoothened mutations in sporadic basal-cell carcinoma. Nature. 1998;391:90–2. doi: 10.1038/34201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lam CW, Xie J, To KF, Ng HK, Lee KC, Yuen NW, Lim PL, Chan LY, Tong SF, McCormick F. A frequent activated smoothened mutation in sporadic basal cell carcinomas. Oncogene. 1999;18:833–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kallassy M, Toftgard R, Ueda M, Nakazawa K, Vorechovsky I, Yamasaki H, Nakazawa H. Patched (ptch)-associated preferential expression of smoothened (smoh) in human basal cell carcinoma of the skin. Cancer Res. 1997;57:4731–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oniscu A, James RM, Morris RG, Bader S, Malcomson RD, Harrison DJ. Expression of Sonic hedgehog pathway genes is altered in colonic neoplasia. J Pathol. 2004;203:909–17. doi: 10.1002/path.1591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shao J, Zhang L, Gao J, Li Z, Chen Z. Aberrant expression of PTCH (patched gene) and Smo (smoothened gene) in human pancreatic cancerous tissues and its association with hyperglycemia. Pancreas. 2006;33:38–44. doi: 10.1097/01.mpa.0000222319.59360.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martin ST, Sato N, Dhara S, Chang R, Hustinx SR, Abe T, Maitra A, Goggins M. Aberrant methylation of the Human Hedgehog interacting protein (HHIP) gene in pancreatic neoplasms. Cancer Biol Ther. 2005;4:728–33. doi: 10.4161/cbt.4.7.1802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taniguchi H, Yamamoto H, Akutsu N, Nosho K, Adachi Y, Imai K, Shinomura Y. Transcriptional silencing of hedgehog-interacting protein by CpG hypermethylation and chromatic structure in human gastrointestinal cancer. J Pathol. 2007;213:131–9. doi: 10.1002/path.2216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tada M, Kanai F, Tanaka Y, Tateishi K, Ohta M, Asaoka Y, Seto M, Muroyama R, Fukai K, Imazeki F, Kawabe T, Yokosuka O, Omata M. Down-regulation of hedgehog-interacting protein through genetic and epigenetic alterations in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:3768–76. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Svard J, Heby-Henricson K, Persson-Lek M, Rozell B, Lauth M, Bergstrom A, Ericson J, Toftgard R, Teglund S. Genetic elimination of Suppressor of fused reveals an essential repressor function in the mammalian Hedgehog signaling pathway. Dev Cell. 2006;10:187–97. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Svard J, Rozell B, Toftgard R, Teglund S. Tumor suppressor gene co-operativity in compound Patched1 and suppressor of fused heterozygous mutant mice. Mol Carcinog. 2009;48:408–19. doi: 10.1002/mc.20479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sheng T, Li C, Zhang X, Chi S, He N, Chen K, McCormick F, Gatalica Z, Xie J. Activation of the hedgehog pathway in advanced prostate cancer. Mol Cancer. 2004;3:29. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-3-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chi S, Huang S, Li C, Zhang X, He N, Bhutani MS, Jones D, Castro CY, Logrono R, Haque A, Zwischenberger J, Tyring SK, Zhang H, Xie J. Activation of the hedgehog pathway in a subset of lung cancers. Cancer Lett. 2006;244:53–60. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2005.11.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reifenberger J, Wolter M, Knobbe CB, Kohler B, Schonicke A, Scharwachter C, Kumar K, Blaschke B, Ruzicka T, Reifenberger G. Somatic mutations in the PTCH, SMOH, SUFUH and TP53 genes in sporadic basal cell carcinomas. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152:43–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06353.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Taylor MD, Liu L, Raffel C, Hui CC, Mainprize TG, Zhang X, Agatep R, Chiappa S, Gao L, Lowrance A, Hao A, Goldstein AM, Stavrou T, Scherer SW, Dura WT, Wainwright B, Squire JA, Rutka JT, Hogg D. Mutations in SUFU predispose to medulloblastoma. Nat Genet. 2002;31:306–10. doi: 10.1038/ng916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rikova K, Guo A, Zeng Q, Possemato A, Yu J, Haack H, Nardone J, Lee K, Reeves C, Li Y, Hu Y, Tan Z, Stokes M, Sullivan L, Mitchell J, Wetzel R, Macneill J, Ren JM, Yuan J, Bakalarski CE, Villen J, Kornhauser JM, Smith B, Li D, Zhou X, Gygi SP, Gu TL, Polakiewicz RD, Rush J, Comb MJ. Global survey of phosphotyrosine signaling identifies oncogenic kinases in lung cancer. Cell. 2007;131:1190–203. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Taja-Chayeb L, Chavez-Blanco A, Martinez-Tlahuel J, Gonzalez-Fierro A, Candelaria M, Chanona-Vilchis J, Robles E, Duenas-Gonzalez A. Expression of platelet derived growth factor family members and the potential role of imatinib mesylate for cervical cancer. Cancer Cell Int. 2006;6:22. doi: 10.1186/1475-2867-6-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang T, Sun HC, Xu Y, Zhang KZ, Wang L, Qin LX, Wu WZ, Liu YK, Ye SL, Tang ZY. Overexpression of platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha in endothelial cells of hepatocellular carcinoma associated with high metastatic potential. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:8557–63. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matei D, Emerson RE, Lai YC, Baldridge LA, Rao J, Yiannoutsos C, Donner DD. Autocrine activation of PDGFRalpha promotes the progression of ovarian cancer. Oncogene. 2006;25:2060–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jechlinger M, Sommer A, Moriggl R, Seither P, Kraut N, Capodiecci P, Donovan M, Cordon-Cardo C, Beug H, Grunert S. Autocrine PDGFR signaling promotes mammary cancer metastasis. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:1561–70. doi: 10.1172/JCI24652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lev DC, Kim SJ, Onn A, Stone V, Nam DH, Yazici S, Fidler IJ, Price JE. Inhibition of platelet-derived growth factor receptor signaling restricts the growth of human breast cancer in the bone of nude mice. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:306–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Russell MR, Jamieson WL, Dolloff NG, Fatatis A. The alpha-receptor for platelet-derived growth factor as a target for antibody-mediated inhibition of skeletal metastases from prostate cancer cells. Oncogene. 2009;28:412–21. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wehler TC, Frerichs K, Graf C, Drescher D, Schimanski K, Biesterfeld S, Berger MR, Kanzler S, Junginger T, Galle PR, Moehler M, Gockel I, Schimanski CC. PDGFRalpha/beta expression correlates with the metastatic behavior of human colorectal cancer: a possible rationale for a molecular targeting strategy. Oncol Rep. 2008;19:697–704. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ma X, Sheng T, Zhang Y, Zhang X, He J, Huang S, Chen K, Sultz J, Adegboyega PA, Zhang H, Xie J. Hedgehog signaling is activated in subsets of esophageal cancers. Int J Cancer. 2006;118:139–48. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sarbia M, Becker KF, Hofler H. Pathology of upper gastrointestinal malignancies. Semin Oncol. 2004;31:465–75. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2004.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bonifas JM, Pennypacker S, Chuang PT, McMahon AP, Williams M, Rosenthal A, De Sauvage FJ, Epstein EH., Jr Activation of expression of hedgehog target genes in basal cell carcinomas. J Invest Dermatol. 2001;116:739–42. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2001.01315.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xie J, Aszterbaum M, Zhang X, Bonifas JM, Zachary C, Epstein E, McCormick F. A role of PDGFRalpha in basal cell carcinoma proliferation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:9255–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.151173398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Heinrich MC, Corless CL, Demetri GD, Blanke CD, von Mehren M, Joensuu H, McGreevey LS, Chen CJ, Van den Abbeele AD, Druker BJ, Kiese B, Eisenberg B, Roberts PJ, Singer S, Fletcher CD, Silberman S, Dimitrijevic S, Fletcher JA. Kinase mutations and imatinib response in patients with metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumor. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:4342–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.04.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barnfield PC, Zhang X, Thanabalasingham V, Yoshida M, Hui CC. Negative regulation of Gli1 and Gli2 activator function by Suppressor of fused through multiple mechanisms. Differentiation. 2005;73:397–405. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.2005.00042.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Karhadkar SS, Bova GS, Abdallah N, Dhara S, Gardner D, Maitra A, Isaacs JT, Berman DM, Beachy PA. Hedgehog signalling in prostate regeneration, neoplasia and metastasis. Nature. 2004;431:707–12. doi: 10.1038/nature02962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang L, Huang SH, Bian YH, Ma XL, Zhang HW, Xie JW. Indentification of signature genes for detecting hedgehog signaling activation in gastric cancer. Molecular Medicine Reports. 2010;3:473–478. doi: 10.3892/mmr_00000283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]