Data from mice lacking all endogenous melanocortin peptides suggest Agouti-related-peptide acts in vivo as a melanocortin antagonist rather than an inverse agonist.

Abstract

The hypothalamic melanocortin system is unique among neuropeptide systems controlling energy homeostasis, in that both anorexigenic proopiomelanocortin (POMC)-derived and orexigenic Agouti related-peptide (AgRP)-derived ligands act at the same receptors, namely melanocortin 3 and 4 receptors (MC3/4R). AgRP clearly acts as a competitive antagonist at MC3R and MC4R but may also have an inverse agonist action at these receptors. The physiological relevance of this remains uncertain. We generated a mouse lacking both POMC and AgRP [double knockout (DKO) mouse]. Phenotyping was performed in the absence and presence of glucocorticoids, and the response to central peptide administration was studied. The phenotype of DKO mice is indistinguishable from that of mice lacking Pomc alone, with both exhibiting highly similar degrees of hyperphagia and increased body length, fat, and lean mass compared with wild-type controls. After a 24-h fast, there was no difference in the refeeding response between Pomc−/− and DKO mice. Similarly, corticosterone supplementation caused an equivalent increase in food intake and body weight in both genotypes. Although the central administration of [Nle4, d-Phe7]-α-MSH to DKO mice caused a decrease in food intake and an increase in brown adipose tissue Ucp1 expression, both of which could be antagonized with the coadministration of AgRP, there was no effect of AgRP alone. These data suggest AgRP acts predominantly as a melanocortin antagonist. If AgRP has significant melanocortin-independent actions, these are of insufficient magnitude in vivo to impact any of the detailed phenotypes we have measured under a wide variety of conditions.

Central melanocortin 3 and 4 receptors (MC3/4-R) are critical regulators of energy homeostasis. MC4Rs have an established role in energy intake and energy expenditure, whereas MC3Rs may have a more subtle involvement in nutrient partitioning (1). These receptors receive inputs from two anatomically distinct subsets of arcuate neurons, which constitute the hypothalamic melanocortin system. The first population of neurons expresses proopiomelanocortin (POMC). The POMC propeptide is processed posttranslationally to produce the melanocortin peptides α-, β-, and γ-MSH. Central administration of melanocortin agonists significantly reduce food intake (2, 3). Furthermore, impairment of either the synthesis (4, 5) or processing (6–8) of POMC results in obesity.

The second neuronal population expresses, among other peptides, Agouti-related peptide (AgRP). Like POMC, AgRP is a propeptide that undergoes processing to produce smaller, active peptides (9). In contrast to melanocortins, central AgRP administration potently stimulates food intake (10). These and many other studies unequivocally show that AgRP is a competitive antagonist of melanocortins at both the MC3R and MC4R (11, 12).

Despite this, a full understanding of the biology of AgRP remains elusive, and there are data to suggest that central melanocortin signaling is rather more complex than a simple competition for binding at MC4R. There is clear asymmetry in hypothalamic Agrp and Pomc expression, with different diurnal variability and response to fasting (13). Furthermore, unlike α-MSH, a single dose of AgRP given centrally can increase food intake for up to a week (14).

AgRP may also act as an inverse agonist at MC4R. In vitro studies indicate that constitutive activity of the MC4R can be dose dependently suppressed by AgRP (15, 16). Further support comes from in vivo data showing that AgRP administration to a transgenic mouse model wholly lacking hypothalamic POMC-derived peptides can still bring about changes in food intake and energy expenditure (17).

We have previously used a mouse model of POMC deficiency (Pomc−/−) to study melanocortin biology (5, 18–20). Pomc−/− mice are hyperphagic, display increased fat and lean mass, and have reduced energy expenditure (5). Pomc−/− mice are also hypersensitive to the adverse metabolic effects of glucocorticoids (19). However, it remains uncertain whether the obese phenotype seen in Pomc−/− mice is due to a lack of melanocortin peptide, the unopposed action of AgRP, or both. Furthermore, it is unclear whether the severe metabolic consequences revealed when Pomc−/− mice are treated with corticosterone are driven by an AgRP-dependent mechanism.

To address these questions, we have generated a mouse model completely lacking all POMC- and AgRP-derived peptides. We have studied the resultant metabolic phenotype in the absence and presence of corticosterone and also used this model to further investigate the role of AgRP in vivo.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Agrp−/− mice [supplied by Dr. Qian (Merck) (21)] were backcrossed 10+ generations onto the 129S2/SVH background (>99.9% 129S2/SVH) before being bred with an existing model of Pomc deficiency on an identical background (5) to generate mice lacking both AgRP and POMC [Pomc−/−/Agrp−/−, double knockout (DKO)]. Mice were group housed with chow (RMI diet; Special Diet Services, Witham, UK) and water available ad libitum unless otherwise stated. All animals were maintained on a 12-h dark, 12-h light cycle (lights on 0700–1900 h) at 21–23 C, and all procedures were conducted under the British Home Office Animals Scientific Procedures Act 1986 (Project License 80/2098) and in accordance with the accepted standards of the local ethical review committee.

Phenotyping

Body length and weight were measured weekly from weaning. All studies of food intake were carried out on single housed animals, acclimatized to this environment. Daily food intake was an average taken from 7 consecutive days. Response to fasting was measured after mice were moved into clean cages, and food was removed at 0700 h for a 24-h period. Energy expenditure was determined using indirect calorimetry in a comprehensive laboratory animal monitoring system (Columbus Instruments, Columbus, OH). Body composition was determined using dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) using a Lunar PIXImus2 mouse densitometer (General Electric Medical Systems, Fitchburg, WI).

Glucose tolerance tests were carried out after an overnight fast. After baseline glucose measure, each animal received a single bolus of glucose by ip injection (1.2 g/kg body weight). Blood glucose was measured at 10, 20, 30, 60, 120, and 180 min using OneTouch Ultra 2 blood glucose monitor (LifeScan Inc., Milpitas, CA) on blood from tail vein.

Tissue and adipose depots were dissected after culling, weighed using an analytical balance (Sartorius, Epson, UK), snap frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 C.

Plasma biochemistry

All blood samples were taken from the inferior vena cava while mice were under terminal anesthesia [phenobarbital sodium (Dolethal); Vétoquinol UK, Buckingham, UK]. Insulin and leptin were assayed using a two-plex electrochemical luminescence microtiter plate immunoassay (MesoScale Discovery, Gaithersburg, MD). Statistical analysis was performed on log-transformed insulin data; however, data are presented as non-log transformed for clarity of interpretation. T4 was measured using a human T4 DELFIA assay kit (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA) with a modified assay protocol to allow the measurement of T4 in rodent samples. Corticosterone was measured using an enzyme immunoassay kit (IDS, Boldon, UK).

Corticosterone supplementation

Study mice were given either corticosterone (Sigma Aldrich, Poole, UK)-supplemented drinking water (25 μg/ml) or normal drinking water for 10 d.

Peptides

AgRP82–131 (mouse) was purchased from Phoenix Peptides (Karlsruhe, Germany). [Nle4, d-Phe7]-α-MSH (NDP-α-MSH), a potent and stable analog of α-MSH previously used in studies of AgRP action (22, 23), was purchased from Bachem (Weil am Rhein, Germany). Lyophilized peptides were dissolved in sterile water immediately before administration.

Intracerebroventricular (icv) administration studies

Methods used were as previously described (20). In brief, mice were anesthetized with a mix of inhaled isoflurane and oxygen, and a 26-gauge steel guide cannula was implanted into the right lateral ventricle using the following coordinates: 1.0 mm lateral from bregma, 0.5 mm posterior to bregma. The guide cannula was secured to the skull and a dummy cannula was inserted. All animals received analgesia (Rimadyl, 5 mg/kg; Pfizer Animal Health, Kent, UK) and antibiotic (Teramycin LA, 60 mg/kg; Pfizer Animal Health) before being returned to their home cage.

All DKO animals used in icv studies received corticosterone-supplemented drinking water for the duration of the study (24). After 1 wk recovery, daily food intake and body weight measurements were started 1 d before peptide treatment. There were four icv treatment groups: 1) 2 nmol NDP-α-MSH, 2) 2 nmol AgRP 82–131, 3) 2 nmol NDP-α-MSH + 2 nmol AgRP 82–131, and 4) 1× PBS. All icv treatments were delivered in a total volume of 2 μl and administered using a Hamilton syringe (Hamilton Co., Reno, NV) over 2 min. Each treatment was given at 0900 h for 3 consecutive days. Twenty-four hours after the final peptide administration, mice were killed with tissue and blood collected as described above.

Quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was purified from whole hypothalamic and brown adipose tissue (BAT) using RNA STAT 60 (AMS Biotechnology, Abington, UK) according to the manufacturer's instructions. cDNA was obtained by reverse transcription of 500 ng RNA. PCR of cDNA was performed in duplicate on an ABI Prism 7900 sequence detection system using Taqman Gene expression assays (both from Applied Biosystems, Warrington, UK) for Pomc, Agrp, Npy, Crh, Mc3r, Mc4r in whole hypothalamus, Ucp1 in brown adipose, and endogenous controls CypA, Gapdh, and Actb.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 5 (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA). One-way ANOVA tests with a Bonferroni posttest were used to test groups and all data are presented as mean ± sem unless otherwise stated.

Results

Expression of hypothalamic genes in Pomc−/− Agrp−/− mice

As expected, Pomc was undetectable in Pomc−/− and DKO mice (P < 0.001), whereas Agrp was undetectable in Agrp−/− and DKO mice (P < 0.01) (Supplemental Fig. 1, published on The Endocrine Society's Journals Online web site at http://endo.endojournals.org). Crh expression was up-regulated in both Pomc−/− and DKO mice (P < 0.001). There was no difference in Mc3r or Mc4r expression between Pomc−/− and DKO mice.

Appearance and body composition of Pomc−/− Agrp−/− mice

Mice lacking both Agrp and Pomc have a similar phenotype to mice lacking Pomc alone, both being obese with a lighter ventral coat color (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

Phenotype of Pomc−/−/Agrp−/− DKO mouse. A, DKO mice have a similar phenotype to Pomc null mice, displaying obesity and a lighter ventral coat color than age-matched wild-type controls. Body weight (B) and body length (C) of wild-type (WT), AgRP knockout (KO), POMC KO, and DKO male mice on normal chow. Statistical significance vs. WT mice. Lean (D) and fat mass (E) of 4- to 5-month-old male mice determined by DEXA. All data represent mean sem. ***, P < 0.001 vs. WT mice. WT (Pomc+/+/Agrp+/+), n = 9; AgRP KO (Pomc+/+/Agrp−/−), n = 8; POMC KO (Pomc−/−/Agrp+/+), n = 9; DKO (Pomc−/−/Agrp−/−), n = 11.

The growth of DKO mice was indistinguishable from Pomc−/− mice, with both heavier than wild-type littermates by 6 wk. By 12 wk, DKO and Pomc−/− mice weighed 42.0 ± 0.9 and 40.5 ± 0.6 g, respectively, with both being approximately 30% heavier than wild-type littermates (28.0 ± 0.6 g, P < 0.001) (Fig. 1B).

Similarly, DKO mice had an equivalent body length phenotype to Pomc−/− mice. By wk 12, DKO and Pomc−/− mice were 9.8 ± 0.1 and 9.6 ± 0.1 cm in length, respectively, being longer than the wild-type littermates (8.8 ± 0.1 cm, P < 0.001) (Fig. 1C). DKO and Pomc−/− mice had an increased lean mass (30.4 ± 2.0 and 29.5 ± 1.5 g, respectively, P < 0.001 vs. their wild-type counterparts at 25.1 ± 2.6 g) (Fig. 1D) and fat mass (12.5 ± 3.1 and 12.1 ± 3.9 g, respectively, P < 0.001 vs. their wild-type counterparts at 5.1 ± 0.9 g) (Fig. 1E).

DKO and Pomc−/− mice were found to have a similar distribution of adipose tissue, and all depots were significantly heavier when compared with wild-type mice (Supplemental Fig. 2).

To determine whether AgRP deficiency promotes a late-onset phenotype in DKO mice, the body composition of 6- to 7-month-old Pomc−/− and DKO male mice was measured. There was no difference in lean mass (29.5 ± 1.9 vs. 30.4 ± 2.1 g, P > 0.05), fat mass (13.0 ± 4.5 vs. 15.9 ± 3.3 g, P > 0.05), total mass (42.5 ± 6.3 vs. 46.3 ± 4.4 g, P > 0.05), or percentage fat (29.8 ± 6.1 vs. 34.1 ± 4.7%, P > 0.05) between Pomc−/− and DKO mice, respectively (Supplemental Fig. 3).

Food intake and energy expenditure of DKO mice

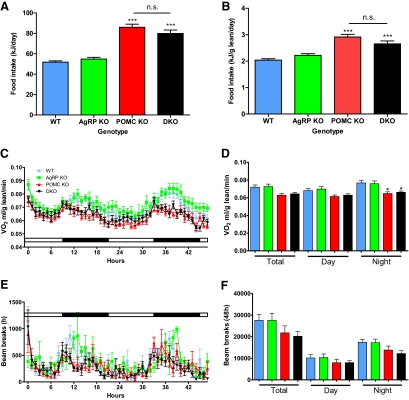

DKO and Pomc−/− mice consumed more food than wild-type mice (79.86 ± 3.33 and 85.93 ± 3.02 kJ, respectively, vs. 51.76 ± 1.33 kJ for wild-type mice, P < 0.05) (Fig. 2A). Food intake remained significantly higher when normalized for lean mass (2.653 ± 0.111 and 2.913 ± 0.102 kJ/g lean mass, respectively, vs. 2.038 ± 0.053 kJ/g lean mass for wild-type mice, P < 0.005) (Fig. 2B). During the dark phase, when normalized for lean mass a significant reduction in oxygen consumption (VO2) was identified in Pomc−/− and DKO mice compared with their wild-type counterparts (Fig. 2, C and D). Pomc−/− and DKO mice had average nighttime VO2 values of 0.065 ± 0.002 and 0.066 ± 0.001 ml/g lean mass per minute, respectively, compared with 0.077 ± 0.003 ml/g lean mass per minute for wild-type counterparts (P < 0.05). There was a nonsignificant trend for decreased ambulatory movement in Pomc−/− and DKO mice, particularly in the dark phase (Fig. 2, E and F).

Fig. 2.

Food intake and energy expenditure of DKO mouse. Total (A) and lean mass (B) corrected daily food intake of 3- to 4-month-old male mice on a normal chow diet. Time course (C) and average day/night lean mass-corrected VO2 values (D) of 3- to 4-month-old male mice determined using indirect calorimetry. Time course (E) and average day/night ambulatory movement (F) of 3- to 4-month-old male mice determined using metabolic cages. Data represent mean sem. *, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.001 vs. WT mice. WT (Pomc+/+/Agrp+/+), n = 9; AgRP KO (Pomc+/+/Agrp−/−), n = 8; POMC KO (Pomc−/−/Agrp+/+), n = 9; DKO (Pomc−/−/Agrp−/−), n = 11.

Plasma biochemistry of DKO mice

Plasma leptin was significantly higher in Pomc−/− and DKO mice (11145.3 ± 8237.7 and 13096.0 ± 8064.9 pg/ml, respectively, both P < 0.01 vs. wild-type mice) compared with wild-type and Agrp null mice (2440.8 ± 2810.1 and 1989.1 ± 1010.5 pg/ml, respectively). As expected, plasma corticosterone was undetectable in Pomc−/− and DKO mice, whereas there was no difference between wild-type and Agrp−/− mice (50.6 ± 64.8 vs. 40.3 ± 31.8 ng/ml, respectively, P > 0.05). There was no significant difference between plasma T4, insulin, or fed blood glucose between any of the genotypes (data not shown), whereas an ip glucose tolerance test showed no significant difference in glucose homeostasis (Supplemental Fig. 4).

Response to fasting in DKO mice

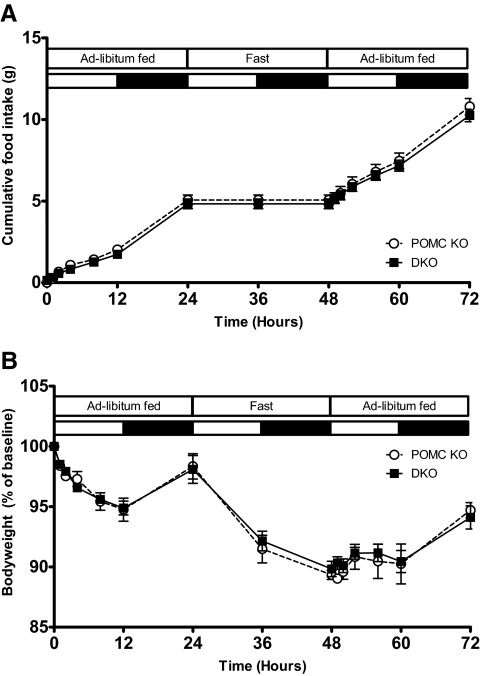

There was no difference in the refeeding response and resulting body weight change between Pomc−/− and DKO mice after a 24-h fast, both in terms of absolute values and also the latency of the refeeding response (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Response of DKO mice to fasting. Cumulative food intake (A) and body weight (B) of 10- to 12-wk-old POMC KO (Pomc−/−/Agrp+/+) and DKO (Pomc−/−/Agrp−/−) female mice over 72 hours with ad libitum feeding (0–24 h), 24 h fast (24–38 h), and ad libitum refeeding (48–72 h). Data represent mean sem. POMC KO, n = 4 (white circles with dotted line); DKO, n = 7 (black squares with solid line).

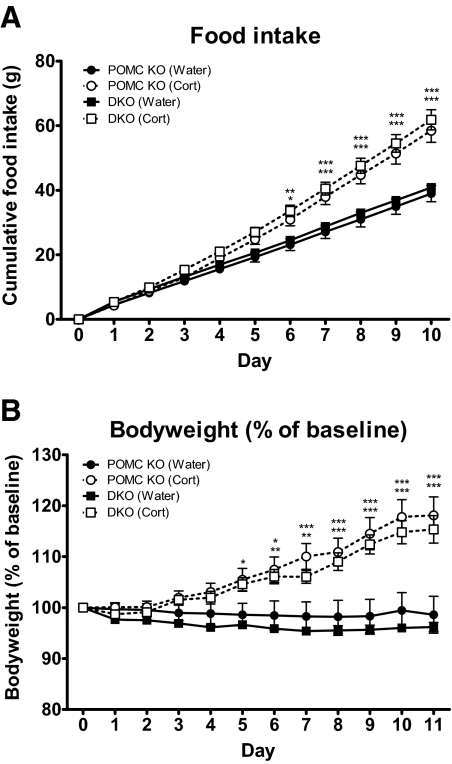

Effect of corticosterone supplementation on DKO mice

Ten days of corticosterone-supplemented drinking water (CORT) led to a 50% increase in cumulative food intake in Pomc−/− mice (38.96 ± 3.03 g vs. 58.43 ± 3.60 g, control and CORT groups, respectively, P < 0.001) (Fig. 4A). A similar increase was also seen in DKO mice given CORT (40.86 ± 2.47 g vs. 61.80 ± 3.96 g, control vs. CORT, P < 0.001).

Fig. 4.

Food intake and body weight after corticosterone supplementation. Cumulative food intake (A) and body weight (B) of corticosterone- (25 μg/ml drinking water) and control-treated POMC KO (Pomc−/−) and DKO (Pomc−/−/Agrp−/−) female mice aged 10–16 wk. Data represent mean total cumulative food intake and mean body weight as percentage of baseline sem. *, P < 0.05, **, P < 0.01, ***, P < 0.001 vs. control-treated mice. DKO (corticosterone), n = 8 (white squares); DKO (control), n = 8 (black squares); POMC KO (corticosterone), n = 8 (white circles); POMC KO (control), n = 8 (black circles).

There was also an equivalent 20% increase in body weight in both Pomc−/− (95.43 ± 3.85 vs. 114.82 ± 5.11% of baseline, control vs. CORT, P < 0.001) and DKO mice (96.20 ± 0.90 vs. 115.36 ± 2.69% of baseline, control vs. CORT, P < 0.001) (Fig. 4B).

The increase in body weight seen in CORT mice was due to an increase in fat mass in both Pomc−/− (94.79 ± 5.97 vs. 152.51 ± 14.06% of baseline, control vs. CORT, P < 0.001) and DKO mice (95.11 ± 2.47 vs. 143.95 ± 5.46% of baseline, control vs. CORT, P < 0.01) with no change observed in lean mass.

CORT had no significant effect on fed blood glucose in either Pomc−/− (9.5 ± 1.1 mmol/liter vs. 7.5 ± 0.1 mmol/liter, control vs. CORT, P > 0.05) or DKO mice (9.9 ± 0.6 mmol/liter vs. 10.4 ± 1.8 mmol/liter, control vs. CORT, for, P > 0.05). However, CORT led to a significant increase in insulin in both Pomc−/− (0.80 ± 0.33 vs. 6.41 ± 1.49 μg/liter, control vs. CORT, P < 0.001) and DKO mice (0.54 ± 0.05 vs. 10.26 ± 3.16 μg/liter, control vs. CORT, P < 0.001). Furthermore, plasma leptin was significantly increased after the corticosterone supplementation in both Pomc−/− (7.2 ± 1.6 vs. 37.3 ± 5.6 ng/ml, control vs. CORT, P < 0.001) and DKO mice (6.3 ± 0.6 vs. 43.7 ± 2.7 pg/ml, control vs. CORT, P < 0.001).

Finally, as expected, Agrp expression was significantly increased in corticosterone treated Pomc−/− mice but undetected in control or corticosterone-treated DKO mice.

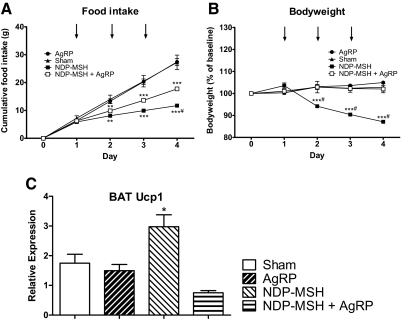

Effect of central administration of AgRP

To validate an effective peptide dose, AgRP was first administered to wild-type mice. Administration of 2 nmol of AgRP (icv, once daily for 3 d) led to a 36% increase in cumulative food intake (14.47 ± 0.57 vs. 19.67 ± 1.45 g, saline vs. AgRP treated groups, respectively, P < 0.001) and a 13% increase in body weight from baseline (97.09 ± 1.04 vs. 112.66 ± 2.48% of baseline, saline vs. AgRP, P < 0.001), whereas there was no body weight increase in saline-treated mice (Supplemental Fig. 5, A and B). This increase in body weight was due to an increase in fat mass (3.70 ± 0.09 vs. 5.03 ± 0.20 g, saline vs. AgRP, P < 0.001) with no change in lean mass (16.3 ± 0.9 vs. 17.1 ± 0.9 g, saline vs. AgRP, P > 0.05) (Supplemental Fig. 5, C and D).

In DKO mice, central administration of 2 nmol NDP-α-MSH once daily for 3 d led to a 55% decrease in cumulative food intake (27.25 ± 2.60 vs. 11.73 ± 0.47 g for saline and NDP-α-MSH groups, respectively, P < 0.001) (Fig. 5A), a 16% decrease in body weight (102.82 ± 1.71 vs. 87.10 ± 0.51%, saline vs. NDP-α-MSH, P < 0.001) (Fig. 5B), and a significant increase in BAT Ucp1 expression (Fig. 5C). Coadministration of 2 nmol AgRP significantly antagonized the potent effect of NDP-α-MSH, restoring food intake to 65% of that seen with saline-treated controls (27.25 ± 2.60 vs. 17.74 ± 0.56 vs. 11.73 ± 0.47 g, saline vs. AgRP + NDP-α-MSH vs. NDP-α-MSH, P < 0.01 for AgRP + NDP-α-MSH vs. NDP-α-MSH groups), maintaining body weight at a level not significantly different from that seen with saline treatment (102.82 ± 1.71 vs. 102.03 ± 1.71 vs. 87.10 ± 0.51%, saline vs. AgRP + NDP-α-MSH vs. NDP-α-MSH groups, P < 0.001 for AgRP + NDP-α-MSH vs. NDP-α-MSH groups) and ameliorating the effect of NDP-α-MSH on BAT Ucp1 expression.

Fig. 5.

Central AgRP administration to DKO mice. Cumulative food intake (A), body weight (B) and quantitative RT-PCR determined expression of BAT uncoupling protein-1 (Ucp1) mRNA (C) of corticosterone-supplemented (2–5 μg/ml drinking water) DKO (Pomc−/−/Agrp−/−) female mice aged 10–16 wk after icv administration of 2 nmol AgRP (black circles), 2 nmol NDP-α-MSH (black squares), 2 nmol AgRP + 2 nmol NDP-α-MSH (white squares), or saline (black triangles). Data represent mean ± sem for food intake and mean body weight as percentage of baseline sem. AgRP, n = 6; NDP-α-MSH, n = 5; AgRP + NDP-α-MSH, n = 5; saline, n = 6. *, P < 0.05, **, P < 0.01, ***, P < 0.001 vs. control treatment; ¥, P < 0.01, #, P < 0.001 vs. AgRP + NDP-α-MSH treatment.

In DKO mice, AgRP administration alone had no effect on cumulative food intake (27.25 ± 2.60 vs. 27.41 ± 1.22 g, saline vs. AgRP, respectively, P > 0.05), body weight (102.82 ± 1.71 vs. 104.96 ± 0.65% of baseline, saline vs. AgRP, P > 0.05), or BAT Ucp1 expression when compared with saline-treated animals. DEXA showed no difference in lean mass (22.2 ± 0.7 vs. 22.2 ± 1.1 g, P > 0.05) or fat mass (13.4 ± 0.8 vs. 13.9 ± 0.9 g, P > 0.05) between saline- and AgRP-treated animals, respectively. Furthermore, AgRP administration had no effect on plasma insulin or leptin.

Discussion

We have generated a novel mouse model lacking both Pomc and Agrp. The phenotype of these DKO mice resembles that of Pomc−/− mice, displaying similar degrees of hyperphagia and obesity. The effect of corticosterone supplementation is also indistinguishable between DKO and Pomc−/− mice. Finally, icv studies in DKO mice have shown that whereas NDP-α-MSH is a potent agonist that can be antagonized by coadministration of AgRP, administration of AgRP alone had no effect on food intake, body weight, or Ucp1 expression in brown adipose, supporting a role for AgRP as an antagonist but not an inverse agonist at melanocortin receptors.

AgRP was first identified when found to be up-regulated in ob/ob and db/db mice (25). Further pharmacological studies (11) and work carried out using transgenic murine models (26) confirmed unequivocally that it is able to bring about robust changes in food intake and body weight through antagonism of central melanocortin receptors. In light of these data, it was surprising that the first study of an Agrp−/− mouse identified a phenotype with normal locomotor activity, growth rates, body composition, food intake, and response to starvation (21). The same study also reported that mice lacking both AgRP and the potent orexigen neuropeptide Y (NPY) appeared indistinguishable from wild-type littermates, leading these authors to conclude that neither AgRP nor NPY had an essential role in feeding behavior. Our reported phenotype of Pomc−/−/Agrp−/− mice is concordant with these observations that congenital absence of AgRP, alone or in combination with a loss of POMC, has no obvious impact on food intake or body weight. Interestingly, a more recent study of an independently generated Agrp−/− mouse identified a modest late-onset lean phenotype with reduced body weight and adiposity after 6 months (27). Although we have not undertaken such an exhaustive study of aged mice, our measurements did not reveal a late-onset phenotype observed in DKO mice with coexisting AgRP deficiency when compared with age-matched Pomc−/− mice.

We have previously shown that corticosterone supplementation of Pomc−/− mice is associated with increased food intake and fat mass (19). Furthermore, a transgenic mouse model in which peripheral melanocortin and corticosterone secretion was restored in Pomc−/− mice has also shown that restoration of peripheral POMC, and therefore restoration of glucocorticoid secretion, leads to increased food intake and fat mass as well as decreased energy expenditure (28). We identified that the increased food intake and fat mass in corticosterone-supplemented Pomc−/− mice was associated with a 200% increase in hypothalamic expression of Agrp. Therefore, we hypothesized that the corticosterone-supplemented phenotype was due to a mechanism involving AgRP, with suppression of Agrp by the hypoadrenal state protecting Pomc-deficient mice from the full adverse metabolic effects of melanocortin deficiency. However, in the current study, there were no discernible differences in Pomc−/− and DKO mice after corticosterone supplementation, indicating that the responses seen previously with corticosterone were not due to a mechanism involving AgRP (19).

Further uncertainties over the role of AgRP include the potential mechanisms underlying both the long-lasting and putative melanocortin-independent effects of AgRP. For example, a single dose of 100 pmol has been reported to produce a robust increase in food intake that persists for an entire week (14), and centrally administered AgRP has been shown to increase food intake in Mc4r−/− mice in a dose-dependent manner (29). However, there are data that counter this, with other studies reporting that administration of AgRP to Mc4r−/− mice has no significant effect on food intake or body weight (30).

A more contentious aspect of AgRP biology relates to its potential action as an inverse agonist at melanocortin receptors. Since the first report by Costa and Herz (31) that δ-opioid receptors can be active in the absence of agonist, an increasing number of G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) have been shown to exhibit spontaneous, constitutive activity in vitro in the absence of agonist, that can be reduced by inverse agonist ligands (32). Mutations resulting in receptor malfunction and constitutive activity in a range of GPCRs such as TSH, LH, and PTH have also been reported (reviewed in Ref. 33). Although there are also data to indicate that histamine H3 receptor can have constitutive activity in vivo (34), questions remain about the physiological relevance of constitutive activity within GPCRs.

Early evidence for AgRP acting as an inverse agonist came from in vitro studies. Nijenhuis et al. (15) showed that MCB16/G4F cell lines transfected with human MC4R had adenylate cyclase activity that correlated with receptor expression level in the clones. Furthermore, they showed that treatment of the cells with AgRP could dose dependently suppress adenylate cyclase activity, consistent with inverse agonist activity at a constitutively active receptor. Similarly, Haskell-Luevano and Monck (16) demonstrated that signaling through a constitutively active MC4R mutant could be dose dependently suppressed by AgRP, supporting the hypothesis that AgRP has inverse agonist activity.

More recently, in vivo evidence indicating that AgRP may have inverse agonist activity has emerged using Pomc−/− mice with an additional transgenic construct that allows expression of Pomc in pituitary cells but not in neurons (Pomc−/−/Tg/+), thereby restoring both peripheral melanocortin and glucocorticoid levels. Central administration of a single dose of 0.5 nmol of AgRP to these mice was reported to increase food intake as well as decrease energy expenditure (17). However, the magnitude and time course of these effects was remarkably different from that seen in wild-type mice. Thus, a single injection of AgRP to wild-type mice caused a significant increase in 24-h food intake in each of the first, second, and third days after administration. In contrast, in Pomc−/−/Tg/+ mice, AgRP had no effect on food intake within the first 24 h or on any of the individual days studied after administration. Significance was reached only after averaging out cumulative food intake between 24 and 72 h. Similarly, AgRP to wild-type mice caused a significant reduction in oxygen consumption in the first 24 h, but again no effect was seen in Pomc−/−/Tg/+ mice until after 24 h and was of a reduced magnitude. Of note, Pomc−/−/Tg/+ mice still respond rapidly (within 2 h) to central administration of the melanocortin agonist melanotan II. Thus, even if Agrp were to be interacting with central melanocortin receptors to modulate energy intake, the disparity of time of onset of effect may be indicative of AgRP-modulating receptor activity in a quite different manner from that of agonist ligands.

The Pomc−/−/Tg/+ transgenic model is similar to our model in that it lacks central POMC-derived peptides yet has restored circulating glucocorticoids (via transgenic restoration and corticosterone supplementation, respectively). However, one potential modifier may be that the transgenic model was largely backcrossed onto a C57BL/6 strain, whereas mice used in the current study were congenic to a 129SV background. Furthermore, the model used by Tolle and Low (17) retains the potential confounding effect of endogenous AgRP-derived ligands. Our model lacks all the endogenous ligands of the central melanocortin system, whereas it is conceivable that in the Pomc−/−/Tg/+ model, a small amount of pituitary-derived melanocortin could have made their way through to the hypothalamus and provided a small subphysiological amount of ligand tone to the central melanocortin system that could then be antagonized by AgRP.

Our data argue against AgRP having an inverse agonist activity at melanocortin receptors in vivo. If constitutive activity of the MCR4 could be suppressed by AgRP in vivo, we would hypothesize an intermediate phenotype for the DKO mouse when compared with the Pomc−/− mouse as predicted by Srinivasan et al. (35) on the basis of in vitro data. Furthermore, if AgRP were an inverse agonist in vivo, we would also anticipate increased food intake after icv administration of AgRP to DKO mice. One caveat is that corticosterone-treated DKO mice already display hyperphagia, and our model system may not have been sensitive enough to detect further increase in food intake brought about by inverse agonist activity. Furthermore, because melanocortin pathways controlling energy balance are known to have regional divergence, with MC4Rs in the paraventricular hypothalamus and/or the amygdala controlling food intake whereas MC4Rs elsewhere control energy expenditure (36), we cannot exclude the hypothesis that this regional specificity extends also to the activity of AgRP, it being an antagonist globally and an inverse agonist only in a limited number of sites. However, it is noteworthy that when judged by the effects on BAT Ucp1 expression, central administration of AgRP revealed antagonist activity only.

So where does this leave our current understanding of AgRP? Taken together, the data reviewed above could be interpreted as being indicative of AgRP having only a minor role in the control of energy balance. However, one explanation for the modest phenotype resulting from loss of Agrp is that mechanisms brought into play by the early loss of peptide, inevitable with germline mutations, are able to compensate for the deficiency. To attempt to overcome this issue, a series of studies undertook to ablate AgRP neurons in adult life. Such an approach brought about more robust phenotype (37–40), with a rapid decline in food intake and body weight after the loss of these neurons. However, because these studies deleted the whole AgRP neuron, and deletion of the neuron is a far greater insult than deletion of the peptide alone (41), the possibility of this effect being due to neuropeptides other than AgRP remained. Indeed, recent studies have shown that starvation after ablation of AgRP neurons is independent of melanocortin signaling (42) and that it is in fact the loss of secretion of γ-aminobutyric acid signaling to the parabrachial nucleus that causes the starvation (43).

Could AgRP also have a role outside of the melanocortin system? There are reports that central administration of AgRP increases ethanol intake in C57BL/6J mice (44), whereas Agrp−/− mice show decreased ethanol self-administration in lever press studies (45). Furthermore, the preference for a high-fat diet after activation of μ-opioid receptors with [d-Ala2, N-Me-Phe4, Gly5-ol]-enkephalin is ameliorated in Agrp−/− mice (46) also suggests that AgRP may impact pathways involved in reward and motivation. However, these mechanisms remain to be fully elucidated.

We believe further studies are required to fully understand the physiological role of AgRP. The true effects of AgRP may require more genetically modified precision being brought to bear, both in terms of neuroanatomical regional loss and in timing of perturbation. Although technically challenging, adult-onset loss of the AgRP peptide alone through the use of conditional or inducible loss may be one possible approach to bring clarity to our understanding of this enigmatic peptide (41).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Su Qian (Merck) for kindly supplying the Agrp−/− mouse. We also thank Keith Burling (Core Biochemical Assay Laboratory, Department of Clinical Biochemistry, Addenbrooke's Hospital, Cambridge, UK) for blood plasma analyses.

M.P.C. is funded by a Medical Research Council-Centre for Obesity and Related Metabolic Disease PhD studentship. S.O. is funded by a Medical Research Council programme grant (G9824984). A.P.C. is funded by the Wellcome Trust (Grant 084748/Z/08/Z). Phenotyping equipment is supported by Medical Research Council-Centre for Obesity and Related Metabolic Disease.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

For editorial see page 1731

- AgRP

- Agouti-related peptide

- BAT

- brown adipose tissue

- DEXA

- dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry

- DKO

- double knockout

- GPCR

- G protein-coupled receptor

- icv

- intracerebroventricular

- MC3/4-R

- melanocortin 3 and 4 receptor

- NDP-α-MSH

- [Nle4, d-Phe7]-α-MSH

- NPY

- neuropeptide Y

- POMC

- proopiomelanocortin

- Pomc−/−

- POMC deficiency

- VO2

- oxygen consumption.

References

- 1. Mountjoy KG. 2010. Functions for pro-opiomelanocortin-derived peptides in obesity and diabetes. Biochem J 428:305–324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Poggioli R, Vergoni AV, Bertolini A. 1986. ACTH-(1–24) and α-MSH antagonize feeding behavior stimulated by κ opiate agonists. Peptides 7:843–848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fan W, Boston BA, Kesterson RA, Hruby VJ, Cone RD. 1997. Role of melanocortinergic neurons in feeding and the agouti obesity syndrome. Nature 385:165–168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Krude H, Biebermann H, Luck W, Horn R, Brabant G, Grüters A. 1998. Severe early-onset obesity, adrenal insufficiency and red hair pigmentation caused by POMC mutations in humans. Nat Genet 19:155–157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Challis BG, Coll AP, Yeo GS, Pinnock SB, Dickson SL, Thresher RR, Dixon J, Zahn D, Rochford JJ, White A, Oliver RL, Millington G, Aparicio SA, Colledge WH, Russ AP, Carlton MB, O'Rahilly S. 2004. Mice lacking pro-opiomelanocortin are sensitive to high-fat feeding but respond normally to the acute anorectic effects of peptide-YY(3–36). Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101:4695–4700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Farooqi IS, Volders K, Stanhope R, Heuschkel R, White A, Lank E, Keogh J, O'Rahilly S, Creemers JW. 2007. Hyperphagia and early-onset obesity due to a novel homozygous missense mutation in prohormone convertase 1/3. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 92:3369–3373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jackson RS, Creemers JW, Farooqi IS, Raffin-Sanson ML, Varro A, Dockray GJ, Holst JJ, Brubaker PL, Corvol P, Polonsky KS, Ostrega D, Becker KL, Bertagna X, Hutton JC, White A, Dattani MT, Hussain K, Middleton SJ, Nicole TM, Milla PJ, Lindley KJ, O'Rahilly S. 2003. Small-intestinal dysfunction accompanies the complex endocrinopathy of human proprotein convertase 1 deficiency. J Clin Invest 112:1550–1560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jackson RS, Creemers JW, Ohagi S, Raffin-Sanson ML, Sanders L, Montague CT, Hutton JC, O'Rahilly S. 1997. Obesity and impaired prohormone processing associated with mutations in the human prohormone convertase 1 gene. Nat Genet 16:303–306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Creemers JW, Pritchard LE, Gyte A, Le Rouzic P, Meulemans S, Wardlaw SL, Zhu X, Steiner DF, Davies N, Armstrong D, Lawrence CB, Luckman SM, Schmitz CA, Davies RA, Brennand JC, White A. 2006. Agouti-related protein is posttranslationally cleaved by proprotein convertase 1 to generate agouti-related protein (AGRP)83–132: interaction between AGRP83–132 and melanocortin receptors cannot be influenced by syndecan-3. Endocrinology 147:1621–1631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rossi M, Kim MS, Morgan DG, Small CJ, Edwards CM, Sunter D, Abusnana S, Goldstone AP, Russell SH, Stanley SA, Smith DM, Yagaloff K, Ghatei MA, Bloom SR. 1998. A C-terminal fragment of Agouti-related protein increases feeding and antagonizes the effect of alpha-melanocyte stimulating hormone in vivo. Endocrinology 139:4428–4431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ollmann MM, Wilson BD, Yang YK, Kerns JA, Chen Y, Gantz I, Barsh GS. 1997. Antagonism of central melanocortin receptors in vitro and in vivo by agouti-related protein. Science 278:135–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cone RD. 2005. Anatomy and regulation of the central melanocortin system. Nat Neurosci 8:571–578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mizuno TM, Makimura H, Silverstein J, Roberts JL, Lopingco T, Mobbs CV. 1999. Fasting regulates hypothalamic neuropeptide Y, agouti-related peptide, and proopiomelanocortin in diabetic mice independent of changes in leptin or insulin. Endocrinology 140:4551–4557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hagan MM, Rushing PA, Pritchard LM, Schwartz MW, Strack AM, Van Der Ploeg LH, Woods SC, Seeley RJ. 2000. Long-term orexigenic effects of AgRP-(83–132) involve mechanisms other than melanocortin receptor blockade. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 279:R47–R52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nijenhuis WA, Oosterom J, Adan RA. 2001. AgRP(83–132) acts as an inverse agonist on the human-melanocortin-4 receptor. Mol Endocrinol 15:164–171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Haskell-Luevano C, Monck EK. 2001. Agouti-related protein functions as an inverse agonist at a constitutively active brain melanocortin-4 receptor. Regul Pept 99:1–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tolle V, Low MJ. 2008. In vivo evidence for inverse agonism of Agouti-related peptide in the central nervous system of proopiomelanocortin-deficient mice. Diabetes 57:86–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Coll AP, Challis BG, Yeo GS, Snell K, Piper SJ, Halsall D, Thresher RR, O'Rahilly S. 2004. The effects of proopiomelanocortin deficiency on murine adrenal development and responsiveness to adrenocorticotropin. Endocrinology 145:4721–4727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Coll AP, Challis BG, López M, Piper S, Yeo GS, O'Rahilly S. 2005. Proopiomelanocortin-deficient mice are hypersensitive to the adverse metabolic effects of glucocorticoids. Diabetes 54:2269–2276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tung YC, Piper SJ, Yeung D, O'Rahilly S, Coll AP. 2006. A comparative study of the central effects of specific proopiomelancortin (POMC)-derived melanocortin peptides on food intake and body weight in pomc null mice. Endocrinology 147:5940–5947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Qian S, Chen H, Weingarth D, Trumbauer ME, Novi DE, Guan X, Yu H, Shen Z, Feng Y, Frazier E, Chen A, Camacho RE, Shearman LP, Gopal-Truter S, MacNeil DJ, Van der Ploeg LH, Marsh DJ. 2002. Neither agouti-related protein nor neuropeptide Y is critically required for the regulation of energy homeostasis in mice. Mol Cell Biol 22:5027–5035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kim MS, Small CJ, Stanley SA, Morgan DG, Seal LJ, Kong WM, Edwards CM, Abusnana S, Sunter D, Ghatei MA, Bloom SR. 2000. The central melanocortin system affects the hypothalamo-pituitary thyroid axis and may mediate the effect of leptin. J Clin Invest 105:1005–1011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kim MS, Rossi M, Abusnana S, Sunter D, Morgan DG, Small CJ, Edwards CM, Heath MM, Stanley SA, Seal LJ, Bhatti JR, Smith DM, Ghatei MA, Bloom SR. 2000. Hypothalamic localization of the feeding effect of agouti-related peptide and α-melanocyte-stimulating hormone. Diabetes 49:177–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Coll AP, Fassnacht M, Klammer S, Hahner S, Schulte DM, Piper S, Tung YC, Challis BG, Weinstein Y, Allolio B, O'Rahilly S, Beuschlein F. 2006. Peripheral administration of the N-terminal pro-opiomelanocortin fragment 1–28 to Pomc−/− mice reduces food intake and weight but does not affect adrenal growth or corticosterone production. J Endocrinol 190:515–525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Shutter JR, Graham M, Kinsey AC, Scully S, Lüthy R, Stark KL. 1997. Hypothalamic expression of ART, a novel gene related to agouti, is up-regulated in obese and diabetic mutant mice. Genes Dev 11:593–602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Graham M, Shutter JR, Sarmiento U, Sarosi I, Stark KL. 1997. Overexpression of Agrt leads to obesity in transgenic mice. Nat Genet 17:273–274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wortley KE, Anderson KD, Yasenchak J, Murphy A, Valenzuela D, Diano S, Yancopoulos GD, Wiegand SJ, Sleeman MW. 2005. Agouti-related protein-deficient mice display an age-related lean phenotype. Cell Metab 2:421–427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Smart JL, Tolle V, Low MJ. 2006. Glucocorticoids exacerbate obesity and insulin resistance in neuron-specific proopiomelanocortin-deficient mice. J Clin Invest 116:495–505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Marsh DJ, Miura GI, Yagaloff KA, Schwartz MW, Barsh GS, Palmiter RD. 1999. Effects of neuropeptide Y deficiency on hypothalamic agouti-related protein expression and responsiveness to melanocortin analogues. Brain Res 848:66–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Fekete C, Marks DL, Sarkar S, Emerson CH, Rand WM, Cone RD, Lechan RM. 2004. Effect of Agouti-related protein in regulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid axis in the melanocortin 4 receptor knockout mouse. Endocrinology 145:4816–4821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Costa T, Herz A. 1989. Antagonists with negative intrinsic activity at Δ opioid receptors coupled to GTP-binding proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 86:7321–7325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bond RA, Ijzerman AP. 2006. Recent developments in constitutive receptor activity and inverse agonism, and their potential for GPCR drug discovery. Trends Pharmacol Sci 27:92–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Parnot C, Miserey-Lenkei S, Bardin S, Corvol P, Clauser E. 2002. Lessons from constitutively active mutants of G protein-coupled receptors. Trends Endocrinol Metab 13:336–343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Arrang JM, Morisset S, Gbahou F. 2007. Constitutive activity of the histamine H3 receptor. Trends Pharmacol Sci 28:350–357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Srinivasan S, Lubrano-Berthelier C, Govaerts C, Picard F, Santiago P, Conklin BR, Vaisse C. 2004. Constitutive activity of the melanocortin-4 receptor is maintained by its N-terminal domain and plays a role in energy homeostasis in humans. J Clin Invest 114:1158–1164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Balthasar N, Dalgaard LT, Lee CE, Yu J, Funahashi H, Williams T, Ferreira M, Tang V, McGovern RA, Kenny CD, Christiansen LM, Edelstein E, Choi B, Boss O, Aschkenasi C, Zhang CY, Mountjoy K, Kishi T, Elmquist JK, Lowell BB. 2005. Divergence of melanocortin pathways in the control of food intake and energy expenditure. Cell 123:493–505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Bewick GA, Gardiner JV, Dhillo WS, Kent AS, White NE, Webster Z, Ghatei MA, Bloom SR. 2005. Post-embryonic ablation of AgRP neurons in mice leads to a lean, hypophagic phenotype. FASEB J 19:1680–1682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Gropp E, Shanabrough M, Borok E, Xu AW, Janoschek R, Buch T, Plum L, Balthasar N, Hampel B, Waisman A, Barsh GS, Horvath TL, Brüning JC. 2005. Agouti-related peptide-expressing neurons are mandatory for feeding. Nat Neurosci 8:1289–1291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Luquet S, Perez FA, Hnasko TS, Palmiter RD. 2005. NPY/AgRP neurons are essential for feeding in adult mice but can be ablated in neonates. Science 310:683–685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Xu AW, Kaelin CB, Morton GJ, Ogimoto K, Stanhope K, Graham J, Baskin DG, Havel P, Schwartz MW, Barsh GS. 2005. Effects of hypothalamic neurodegeneration on energy balance. PLoS Biol 3:e415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Flier JS. 2006. AgRP in energy balance: will the real AgRP please stand up? Cell Metab 3:83–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wu Q, Howell MP, Cowley MA, Palmiter RD. 2008. Starvation after AgRP neuron ablation is independent of melanocortin signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105:2687–2692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Wu Q, Boyle MP, Palmiter RD. 2009. Loss of GABAergic signaling by AgRP neurons to the parabrachial nucleus leads to starvation. Cell 137:1225–1234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Navarro M, Cubero I, Chen AS, Chen HY, Knapp DJ, Breese GR, Marsh DJ, Thiele TE. 2005. Effects of melanocortin receptor activation and blockade on ethanol intake: a possible role for the melanocortin-4 receptor. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 29:949–957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Navarro M, Cubero I, Ko L, Thiele TE. 2009. Deletion of agouti-related protein blunts ethanol self-administration and binge-like drinking in mice. Genes Brain Behav 8:450–458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Barnes MJ, Argyropoulos G, Bray GA. 2010. Preference for a high fat diet, but not hyperphagia following activation of mu opioid receptors is blocked in AgRP knockout mice. Brain Res 1317:100–107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.