Abstract

We address the advantages and challenges of service delivery models based on student response to intervention (RTI) for preventing and remediating academic difficulties and as data sources for identification for special education services. The primary goal of RTI models is improved academic and behavioral outcomes for all students. We review evidence for the processes underlying RTI, including screening and progress monitoring assessments, evidence-based interventions, and schoolwide coordination of multitiered instruction. We also discuss the secondary goal of RTI, which is to provide data for identification of learning disabilities (LDs). Incorporating instructional response into identification represents a controversial shift away from discrepancies in cognitive skills that have traditionally been a primary basis for LD identification. RTI processes potentially integrate general and special education and suggest new directions for research and public policy related to LDs, but the scaling issues in schools are significant and more research is needed on the use of RTI data for identification.

Children struggle to learn reading, mathematics, and writing skills for many reasons, including growing up in economically disadvantaged settings, low proficiency in English, emotional difficulties, and even inadequate academic instruction (Donovan & Cross, 2002). Some children are eventually identified with learning disabilities (LDs), representing approximately 5% of the school-age population and approximately 50% of students identified with disabilities in schools (U.S. Department of Education, 2007).

A variety of state, federal, and district school-based programs attempt to address different obstacles to learning academic skills. With the 2002 passage of the No Child Left Behind Act, which targets the needs of economically disadvantaged children through Title I funding, the federal government placed greater emphasis on early intervention, high-quality instruction, and accountability for academic outcomes. In 2004, the Individuals with Disabilities in Education Act (IDEA; U.S. Department of Education, 2004), which governs the provision of special education services in U.S. public schools, was also reauthorized.

Noteworthy in the reauthorization was the emphasis on early intervention services and specific provisions allowing districts to adopt service delivery models that focus on the child’s response to intervention (RTI). These models (a) screen all children for academic and behavioral problems; (b) monitor the progress of children at risk for difficulties in these areas; and (c) provide increasingly intense interventions based on the response to progress monitoring assessments (Vaughn & Fuchs, 2003). Those children who do not respond adequately may be referred for a comprehensive evaluation for eligibility for special education services. Through the comprehensive evaluation, some children will be eligible for special education and others may need alternative services because their difficulties in learning are not due to an LD or other type of disability consistent with a need for special education.

Service delivery models that provide universal screening, progress monitoring, and tiered, or layered, interventions have been widely adopted in No Child Left Behind and Title I and are a specific focus of IDEA 2004. We discuss the research and policy basis for these models, focusing only on academic difficulties (primarily reading) and noting that there is comparable development of RTI models in the behavioral area (Walker, Stiller, Serverson, Feil, & Golly, 1998).

Multitiered Intervention Models and RTI

What Are RTI Models?

RTI models are multitiered service delivery systems in which schools provide layered interventions that begin in general education and increase in intensity (e.g., increased time for instruction to smaller groups of students) depending on the students’ instructional response. There are many approaches to the implementation of RTI models, which are best considered as a set of processes and not a single model, with variation in how the processes are implemented. These approaches have at least two historical origins, both representing efforts to implement prevention programs in schools.

The first source involves schoolwide efforts to prevent behavior problems (Donovan & Cross, 2002; Walker et al., 1998). These models are associated with a problem-solving process in which a shared decision-making team identifies a behavior or academic problem, proposes strategies that address the problem, evaluates the outcome, and then reconvenes to consider whether the problem has been resolved, leading to improvements in behavior or learning (Reschly & Tilly, 1999).

The second origin derives from research on preventing reading difficulties in children. These approaches typically use standardized protocols to deliver interventions increasing in intensity and differentiation depending on the child’s instructional response. Both models have been significantly influenced by public health models of disease prevention that differentiate primary, secondary, and tertiary levels of intervention that increase in cost and intensity depending on the patient’s response to treatment (Vaughn, Wanzek, & Fletcher, 2007).

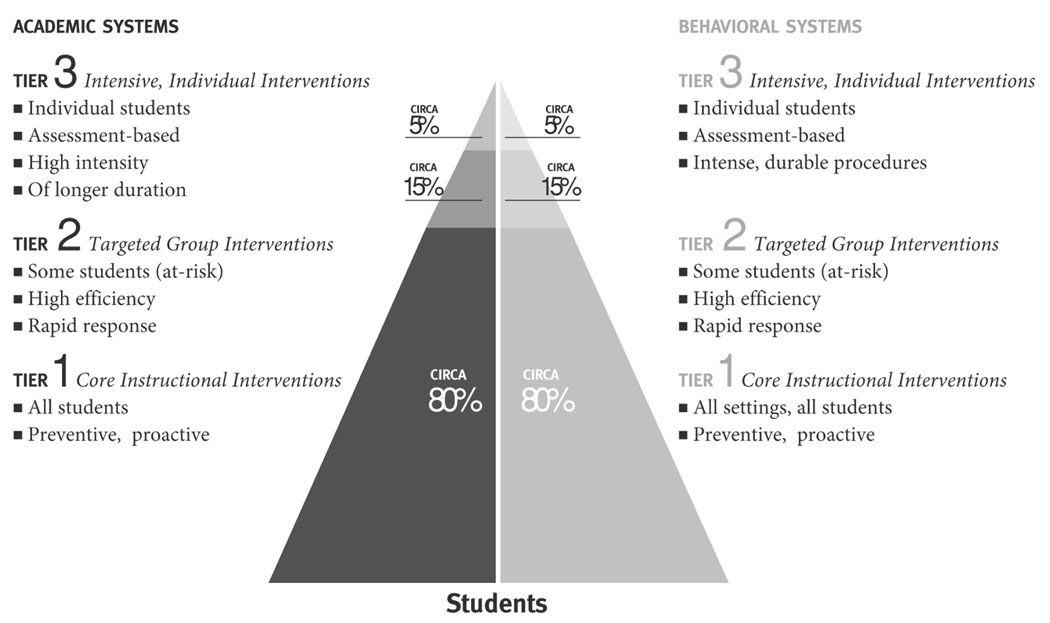

In a common implementation of a standard protocol model (Figure 1; Vaughn, Wanzek, Woodruff, & Linan-Thompson, 2006), all students are screened and those at risk for academic problems are assessed frequently (every 1–4 weeks) on short probes designed to assess progress over time (Stecker, Fuchs, & Fuchs, 2005). Classroom teachers receive professional development in effective instruction and ways to enhance differentiation and intensity through flexible grouping strategies and evaluations of progress (Tier 1, primary intervention). Children who do not achieve specified levels of progress based on local or national benchmarks receive additional instruction in small groups of three to five students for 20–40 minutes daily (Tier 2, secondary intervention). If the child does not make adequate progress in secondary intervention, an even more intensive and individualized intervention (Tier 3, tertiary intervention) is provided that may involve smaller groups, increased time in intervention (45–60 minutes daily), and a more specialized teacher. Progress is monitored weekly or biweekly. These models link with special education because inadequate instructional response allows for determination of adequate and inadequate responders and provides a framework for implementing seamless interventions between general and special education.

Figure 1.

A three-tier model for increasingly intense academic and behavioral interventions. The percentages represent estimates of the number of children who are at grade level (Tier 1) and who require Tier 2 and Tier 3 services. Note. From Response to Intervention: Policy Considerations and Implementation (p. 22), National Association of State Directors of Special Education, Inc., 2006, Alexandria, VA: Author. Copyright 2006 by the National Association of State Directors of Special Education, Inc. Reprinted with permission.

The implementation of both problem-solving and standardized protocol models is a significant effort. First, providing effective Tier 1 instruction to all students requires ongoing professional development, screening, and progress monitoring of students. Maintaining these practices demands an extensive professional development regiment from well-trained and committed professionals that are not readily available (NASDSE, 2006). Second, Tier 2 intervention is continuous. Although effective Tier 1 reduces the number of students at risk, significant numbers of students (as many as 20%–25% in early reading; Vaughn et al., 2006) require supplemental interventions by trained personnel (e.g., classroom teachers, paraprofessionals). Finally, many school districts do not perceive that they have the personnel and resources to effectively implement all of the elements of RTI models. Nonetheless, over the past 20 years, many school districts have implemented RTI models from kindergarten to high school (Jimerson, Burns, & VanDerHeyden, 2007).

Screening and Progress Monitoring

A key component of RTI models is universal screening of all children for academic problems. The screening instrument can be norm-referenced or criterion-referenced, the latter often representing the first assessment of a progress monitoring tool. Because screening devices are used with entire grades, the key is that the tool can be quickly administered with adequate sensitivity and specificity. In general, screenings tend to overidentify children as being at risk because the consequence is that students’ progress is monitored and/or they are provided a supplemental intervention to enhance their performance in reading or math (Fletcher, Lyon, Fuchs, & Barnes, 2007).

The most common implementation of a progress monitoring measure involves a technology known as curriculum-based measurement (CBM), which provides brief (1–3 minutes per child) assessments that are readily administered and interpreted by classroom teachers and useful for adjusting instruction (Fuchs, Deno, & Mirkin, 1984). Typically, a child reads a list of words or a short passage appropriate for his or her grade level (or does a set of math computations, spells words, etc.). The number of words (or math problems or spelling items) correctly read (or computed or spelled) is graphed over time and compared against grade-level benchmarks.

There is a substantial research base showing that, when used by classroom teachers, CBM provides reliable and valid information about how well students are progressing and is associated with improved outcomes (Stecker et al., 2005). Controlled studies document that when CBM implementation is compared to classrooms not using CBM, better end-of-year academic outcomes result because teachers modify goals and adjust instruction (e.g., Fuchs, Fuchs, & Hamlett, 1989a, 1989b; Fuchs, Fuchs, Hamlett, & Stecker, 1991). Serial assessments based on CBM have also been used to provide data for eligibility decisions involving education services (Fuchs & Fuchs, 1998).

Despite the value of CBM measures, there are concerns about equivalency of text passages (Francis et al., in press). In addition, it is unclear how reliably benchmarks from these CBM-type measures can be used to determine movement across the tiers, and when used, whether the best benchmarks are at the district or national level. Finally, the use of CBM measures as part of the eligibility process is especially controversial, and there are no widely accepted criteria for identification of inadequate responders. Thus, instructional response is not recommended as the sole determinant of eligibility for special education.

Evidence-Based Interventions

RTI models depend on the implementation of evidence-based interventions designed to prevent or remediate academic difficulties. Numerous syntheses and meta-analyses address the efficacy of interventions for students with academic difficulties. Although a complete analysis is beyond this article, the most comprehensive meta-analysis on interventions for children identified with LDs was conducted by Swanson, Hoskyn, and Lee (1999), who reviewed and analyzed 180 intervention studies over a 30- year period. Their findings suggested moderate to high effects across studies (0.79) and higher effect sizes for interventions conducted in resource room settings (0.86) than those in general education classes (0.48).

Wanzek and Vaughn (2007) synthesized studies of extensive reading interventions defined as at least 100 sessions (i.e., approximately 20 weeks of daily intervention). The effects were diverse, but most studies reported effect sizes in the moderate to large range. Effect sizes were usually larger if the study (a) involved students in kindergarten and grade 1 as opposed to grades 2–5, (b) used a comprehensive reading program, and (c) delivered the intervention one-on-one or in small groups.

In another recent meta-analysis, Scammacca et al. (2007) examined outcomes from intervention studies conducted with older students with reading difficulties. The overall effect size across all 31 studies in Scammacca et al. (2007) was 0.95, with a lower overall effect size when only standardized, norm-referenced measures were used (0.42). For 23 intervention studies that measured reading comprehension, often with experimenter-designed measures, the effect size was 1.33; for standardized achievement reading measures, the effect size was 0.35. The overall findings indicate that for older students with reading difficulties (a) adolescence is not too late to intervene, (b) students benefit from both word-level and text-level interventions, (c) instruction in reading comprehension strategies is associated with large effects, (d) students are able to learn the meanings of words they are taught, and (e) both researcher-implemented and teacher-implemented interventions are effective. However, it may take more intensity and a longer period of time to bring older children with reading difficulties to grade level, which is why prevention efforts are receiving greater emphasis (Torgesen et al., 2001).

Graham and Perrin (2007a, 2007b) provided meta-analyses on effective writing practices. They identified several instructional practices that are associated with improved outcomes for students, including (a) writing strategies that involve explicitly teaching students to plan, revise, brainstorm, and edit (0.82); (b) summarizing through writing (0.82); (c) collaborating with other students in small groups to provide feedback and write cooperatives (0.75); (c) assigning students reasonable goals for improving writing (0.70); and (d) other practices such as word processing, sentence combining, and writing process, which all yield small to medium effect sizes.

There is less intervention research in the academic area of mathematics, although recent research implementing RTI-type frameworks is promising (Fuchs et al., 2005). Baker, Gersten, and Lee (2002) completed an empirical synthesis that revealed that effective mathematics instruction provides data or recommendations to teachers and students (0.57), uses peer-pairing to support learning (0.62), provides explicit instruction directed by the teacher including teacher-facilitated approaches (0.58), and provides practices for communicating student successes to parents (0.42).

Coordinated Systems of Service Delivery

Despite the research base supporting the assessment and intervention components of RTI, the most daunting aspects involve schoolwide implementation, where the scaling issues are significant. Intervention services in schools are often funded by separate entitlement programs, especially Title I and IDEA, that tend to have specific eligibility criteria and historically have made it difficult to blend resources to support schoolwide intervention models. These programs are often isolated from general education and the classroom, so that instruction can be fragmented. Because it may take several years to change practice in implementing RTI models, especially given the entrenchment of older ways of thinking about instruction, schools should move slowly and with care (NASDSE, 2006). Resources will be a concern in many districts unless careful appraisals are made of the available resources, which are typically redeployed to support RTI models of service delivery. A negative consequence of the fact that RTI is recommended under the new reauthorized IDEA 2004 is that many educators perceive RTI as simply a special education initiative. In fact, implementation of RTI models requires close collaboration and implementation with general education, special education, Title I, and other entitlement programs.

Scaling issues are also complicated because of incompleteness in the intervention evidence base. The question of how to implement RTI models in secondary schools is daunting, especially given weaknesses in research studies on interventions and progress-monitoring tools for older students. It seems difficult to conceive of RTI models when the prevention component is not strongly implemented. Although there are data on intensive Tier 3 interventions, they have been infrequently applied as part of a multitiered intervention, reflecting in part the sheer cost of research studies based on a multitiered intervention model. Because few studies have been done of children defined as inadequate responders in an RTI model, the efficacy of a layered Tier 3 intervention in this context is not well established. Preliminary evidence suggests that many of these students are difficult to teach, with approximately half showing insufficient progress to read at grade-appropriate levels even after receiving a yearlong intervention followed by additional intense interventions (16 weeks) in grades 1–3 (Denton, Fletcher, Anthony, & Francis, 2006). However, studies of multitiered intervention models yield rates of inadequate responders for early reading as low as 2%–5% (Berninger et al., 2003; Mathes et al., 2005; McMaster, Fuchs, Fuchs, & Compton, 2005; Torgesen, 2000). Because the number of students who need intense interventions may be greatly reduced, schools may be able to devote the resources needed for effective remediation of inadequate responders (Burns, Appleton, & Stehouwer, 2005; VanDerHeyden, Witt, & Gilbertson, 2007).

Despite these issues, there are successful district-wide implementations of RTI models across the country (Jimerson et al., 2007; NASDSE, 2006). Many of these implementations report an increase in overall academic achievement scores and a decrease in special education referrals (e.g., VanDerHeyden et al., 2007). More research focusing on how schools successfully implement (and struggle to implement) RTI models will be needed. This research must look at outcomes in relation to historical data so that it will be clear that RTI models improve outcomes for all students, including those who are at risk and not at risk for academic difficulties. Furthermore, scaling these models nationally will be a significant task.

RTI Models and Special Education

The specific provisions in IDEA 2004 for RTI models have been controversial in the area of special education. This controversy focuses primarily on two issues, the first representing the scaling issues reviewed above. The second issue is the use of RTI models in the identification of LDs. In contrast to 30 years of implementation, IDEA 2004 allows school districts to implement RTI models and move away from identification models that have relied on a discrepancy between IQ and achievement. Instead, identification relies on inadequate instructional response and other criteria, minimizing the role of IQ and other assessments attempting to identify discrepancies in cognitive ability for identification. Given how entrenched the latter assessments are in the everyday practice of evaluating students, this controversy is not surprising. However, the changes in IDEA 2004 reflect concerns about (a) the effectiveness of traditional implementations of special education in schools and (b) the use of IQ-achievement discrepancies for identification.

Intervention

There is a major disconnection between what is known about efficacy of instruction for students with academic difficulties and how students are taught in schools, especially for students most at risk for academic and behavioral difficulties. Studies of outcomes for students placed in special education show flat levels of growth and little evidence that typical interventions close the achievement gap (Bentum & Aaron, 2003; Donovan & Cross, 2002; Glass, 1983; Hanushek, Kain, & Rivkin, 1998; Torgesen et al., 2001; Vaughn, Levy, Coleman, & Bos, 2002). The interest in RTI is fueled in part by the focus on instructional outcomes and the attempt to reduce the number of students who need the most intense intervention. As we reviewed above, the most consistent evidence about improving outcomes for students identified with LDs addresses preventing or remediating specific academic skills, where the focus on academic domains is especially important (Fletcher et al., 2007). These children are subjected to a potpourri of interventions involving the eyes, brain, and perceptual processes that do not involve reading, writing, and math. The former interventions show little generalization to academic successes for these students (Mann, 1979; Vellutino, Fletcher, Scanlon, & Snowling, 2004).

Identification

Although deficits in specific cognitive functions are strongly associated with different types of LD, a focus on interindividual differences and discrepancies has not proven to be a reliable practice for identification (Francis et al., 2005; Shepard, 1980; Stuebing et al., 2002; Siegel, 1992) and does not lead to implementation of appropriate interventions resulting in strong outcomes (Mann, 1979; Vaughn & Linan-Thompson, 2003). These concerns are especially significant for the use of IQ-achievement discrepancy models of identification.

Two meta-analyses highlight the concerns about the validity of IQ-discrepancy models (Hoskyn & Swanson, 2000; Stuebing et al., 2002). Across studies, both found negligible to small overall effect size differences between IQ-discrepant and nondiscrepant poor readers, with negligible differences on most measures of reading and phonological processing. Other studies comparing poor readers with and without significant IQ-achievement discrepancies find no difference in prognosis (Francis, Shaywitz, Stuebing, Shaywitz, & Fletcher, 1996; Share, McGee, & Silva, 1989) or response to instruction (Vellutino, Scanlon, & Lyon, 2000). These validity issues do not support the 30-year-old practice instantiated in schools and clinics of identifying LDs on the basis of a discrepancy between IQ and achievement (Donovan & Cross, 2002).

RTI Models and Identification

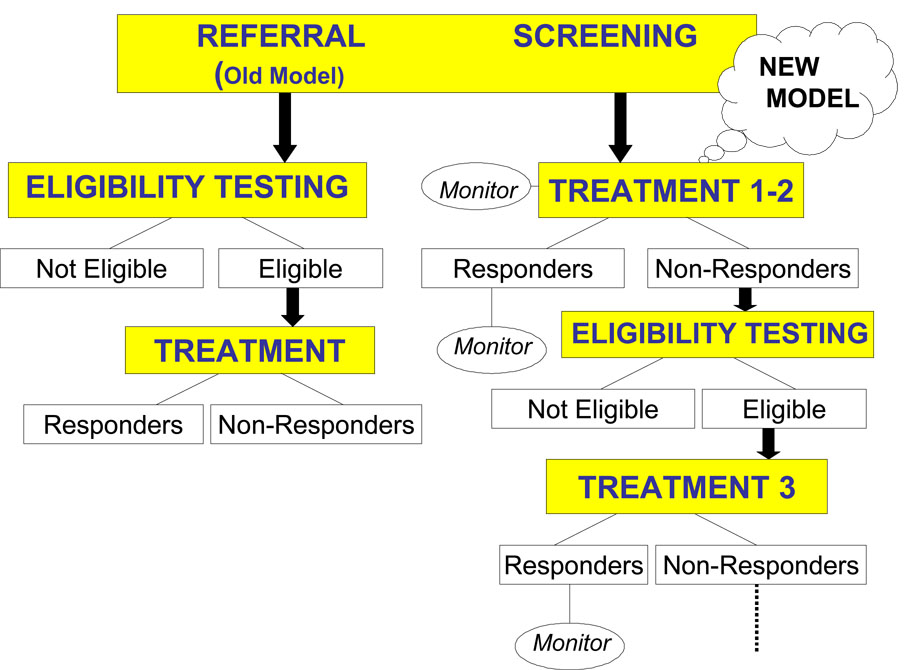

RTI models specifically de-emphasize cognitive discrepancies in the identification process, focusing instead on discrepancies relative to age-based expectations and instruction. Thus, the eligibility process in an RTI model is different from the traditional model (see Figure 2). In an RTI model, children have been screened and monitored early in schooling as opposed to traditional eligibility models that depend on referral, usually in the later grades and after failure. In addition, the data on instructional response lead to evaluations that ask how to best teach the child and that deemphasize the search for cognitive discrepancies.

Figure 2.

A comparison of a traditional eligibility process and a process incorporating response to instruction (RTI) in a three-tier model. On the left side, the student is referred for an eligibility evaluation. The student is either eligible or not eligible; if eligible, the student receives intervention that is evaluated for one to three years. In an RTI model, all students are screened and those at-risk receive progress monitoring and intervention in the general education classroom. If the response to different interventions is not sufficient to meet progress monitoring benchmarks, increasingly intense interventions are provided. If inadequate instructional response continues, the student may be referred for an eligibility evaluation, which would be different because the student was identified as at-risk earlier and the availability of data on instructional response to influence the type of evaluation that is conducted. Note. From Fletcher et al., Learning Disabilities: From Identification to Intervention (p. 161), Guilford Press, New York, 2007. Copyright 2007 by Guilford Press. Reprinted with permission.

The use of instructional response data, however, is unlikely to address all problems related to identifying students with LDs. Within IQ-discrepancy models, one of the persistent problems has been the use of rigid “cut points” for identification of LDs. The use of rigid cut-points for benchmarks and establishing students as high or low responders to instruction could yield the same types of problems with reliability and validity of identification in RTI models. A problem with cognitive discrepancy models is that the attributes (IQ, cognitive processes, achievement) are usually continuous and normally distributed when children with brain injury are excluded from the sample (Lewis, Hitch, & Walker, 1994; Shaywitz, Escobar, Shaywitz, Fletcher, & Makuch, 1992; but see Rutter & Yule, 1975, which did not exclude brain injury). Deciding reliably where on this continuum a disability resides is inherently arbitrary and must rely on criteria other than IQ and achievement scores (Francis et al., 2005). However, instructional response may also exist on a continuum that has no inherent qualitative breaks. Criteria for inadequate response may be as arbitrary as a cut-point on an achievement dimension, and simply creating formulae without testing their validity will be no better than IQ-discrepancy models. The use of confidence intervals and an evaluation of the consequences of different decisions to intervene or not intervene will help with this issue. Validating decisions against other adaptive criteria not directly tied to academic achievement would also help determine the adequacy of decisions. Research is also needed to evaluate the reliability and validity of decisions made by experts and not decisions based solely on statistical criteria.

LD Identification Requires Multiple Criteria

Children cannot be identified with LDs solely on the basis of instructional response. The consensus group of researchers convened for the Learning Disabilities Summit (Bradley, Danielson, & Hallahan, 2002) suggested that three criteria were important: (1) response to instruction, assessed through progress monitoring and evaluations of the integrity of interventions; (2) assessment of low achievement, typically through norm-referenced achievement tests; and (c) application of exclusionary criteria to ensure that low achievement is not due to another disability (e.g., mental retardation, sensory disorder) or to environmental and contextual factors (e.g., limited English proficiency).

IDEA 2004 is consistent with this hybrid model of classification. It explicitly indicates that children may be identified for special education only with documentation that low achievement is not the result of inadequate instruction. In addition, IDEA identifies six domains of low academic achievement in which LDs may occur. It requires assessment of the traditional exclusionary criteria, a process that remains inherently vague when the issues are factors such as emotional difficulties, which may co-exist or result from poor achievement, or economic disadvantage, the role of which in relation to low achievement is difficult to separate from LD in the absence of adequate instruction.

Conclusions

The primary goal of RTI models is the prevention and remediation of academic and behavioral difficulties through effective classroom instruction and increasingly intense interventions. A secondary goal of RTI models is the provision of useful data that contributes to referral and decision making about students with LDs. If the scaling issues can be addressed, districts that successfully implement RTI models may improve achievement and behavioral outcomes in all students, especially those most at risk for academic difficulties.

Regardless of the identification model employed by schools, IDEA 2004 requires an assessment of instructional response. Definitions of LD have always relied on the elimination of known causes of low achievement, which include inadequate instruction. Those children who do not show evidence of an exclusionary condition and who have a cognitive discrepancy have been considered “unexpected” underachievers, which is the core construct historically underlying LD (Hammill, 1993). If inadequate response to quality instruction can be formally assessed, it represents an inclusionary criterion indicating the presence of intractability in instruction. A different type of child will emerge with LDs if formal assessment of inadequate instructional response is part of the definition. This subgroup of inadequate responders who show low achievement and who do not have other disabilities or environmental factors that explain low achievement may epitomize what is meant by unexpected underachievement. It is likely that research on cognitive and neurobiological correlates of LD will begin to focus on children identified under this model and move away from what historically have been samples that are a mixture of students with adequate and inadequate instructional histories. The result may be new approaches to instruction and new understandings of the neurobiological and environmental factors that underlie academic difficulties and LD.

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by a grant from the National Institute for Child Health and Human Development, 1 P50 HD052117, Texas Center for Learning Disabilities.

Contributor Information

Jack M. Fletcher, Department of Psychology, University of Houston, Houston TX

Sharon Vaughn, Department of Special Education, College of Education, University of Texas-Austin, Austin TX.

References

- Baker S, Gersten R, Lee D. A synthesis of empirical research on teaching mathematics to low-achieving students. The Elementary School Journal. 2002;103:336–358. [Google Scholar]

- Bentum KE, Aaron PG. Does reading instruction in learning disability resource rooms really work? A longitudinal study. Reading Psychology. 2003;24:361–369. [Google Scholar]

- Berninger VW, Vermeulen K, Abbott RD, McCutchen D, Cotton S, Cude J, et al. Comparison of three approaches to supplementary reading instruction for low-achieving second-grade readers. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools. 2003;34(2):101–116. doi: 10.1044/0161-1461(2003/009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley R, Danielson LE, Hallahan DP. Identification of learning disabilities: Research to practice. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Burns M, Appleton JJ, Stehouwer JD. Meta-analytic review of responsiveness-to-intervention research: Examining field-based and research-implemented models. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment. 2005;23:381–394. [Google Scholar]

- Denton CA, Fletcher JM, Anthony JL, Francis DJ. An evaluation of intensive intervention for students with persistent reading difficulties. Journal of Learning Disabilities. 2006;39(5):447–466. doi: 10.1177/00222194060390050601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donovan MS, Cross CT National Research Council Committee on Minority Representation in Special Education. Minority students in special and gifted education. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher JM, Lyon GR, Fuchs LS, Barnes MA. Learning disabilities: From identification to intervention. New York: Guilford; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Francis DJ, Fletcher JM, Stuebing KK, Lyon GR, Shaywitz BA, Shaywitz SE. Psychometric approaches to the identification of LD: IQ and achievement scores are not sufficient. Journal of Learning Disabilities. 2005;38(2):98–108. doi: 10.1177/00222194050380020101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis DJ, Santi KL, Barr C, Fletcher JM, Varisco A, Foorman BR. Form effects on the estimation of students’ oral reading fluency using DIBELS. Journal of School Psychology. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2007.06.003. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis DJ, Shaywitz SE, Stuebing KK, Shaywitz BA, Fletcher JM. Developmental lag versus deficit models of reading disability: A longitudinal, individual growth curves analysis. Journal of Educational Psychology. 1996;88:3–17. [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs LS, Compton DL, Fuchs D, Paulsen K, Bryant JD, Hamlett CL. The prevention, identification, and cognitive determinants of math difficulty. Journal of Educational Psychology. 2005;97:493–513. [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs LS, Deno SL, Mirkin PK. The effects of frequent curriculum-based measurement and evaluation on student achievement, pedagogy, and student awareness of learning. American Educational Research Journal. 1984;21:449–460. [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs LS, Fuchs D. Treatment validity: A unifying concept for reconceptualizing the identification of learning disabilities. Learning Disabilities Research and Practice. 1998;13:204–219. [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs LS, Fuchs D, Hamlett CL. Effects of alternative goal structures within curriculum-based measurement. Exceptional Children. 1989a;55:429–438. [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs LS, Fuchs D, Hamlett CL. Effects of instrumental use of curriculum-based measurement to enhance instructional programs. Remedial and Special Education. 1989b;102:43–52. [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs LS, Fuchs D, Hamlett CL, Stecker PM. Effects of curriculum-based measurement and consultation on teacher planning and student achievement in mathematics operations. American Educational Research Journal. 1991;28:617–641. [Google Scholar]

- Glass G. Effectiveness of special education. Policy Studies Review. 1983;2:65–78. [Google Scholar]

- Graham S, Perin D. A meta-analysis of writing instruction for adolescent students. Journal of Educational Psychology. 2007a;99(3):445–476. [Google Scholar]

- Graham S, Perin D. Writing next: Effective strategies to improve writing of adolescents in middle and high schools—A report to Carnegie Corporation of New York. Washington, DC: Alliance for Excellent Education; 2007b. [Google Scholar]

- Hammill DD. A brief look at the learning disabilities movement in the United States. Journal of Learning Disabilities. 1993;26(5):295–310. doi: 10.1177/002221949302600502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanushek EA, Kain JF, Rivkin SG. Does special education raise academic achievement for students with disabilities? Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research; 1998. (Working Paper No. 6690) [Google Scholar]

- Hoskyn M, Swanson HL. Cognitive processing of low achievers and children with reading disabilities: A selective meta-analytic review of the published literature. School Psychology Review. 2000;29(1):102–119. [Google Scholar]

- Jimerson SR, Burns MK, VanDerHeyden AM. Handbook of response to intervention: The science and practice of assessment and intervention. Springfield, IL: Charles E. Springer; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis C, Hitch GJ, Walker P. The prevalence of specific arithmetic difficulties and specific reading difficulties in 9- to 10-year-old boys and girls. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1994;35:283–292. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1994.tb01162.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann L. On the trail of process. New York: Grune & Stratton; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Mathes PG, Denton CA, Fletcher JM, Anthony JL, Francis DJ, Schatschneider C. The effects of theoretically different instruction and student characteristics on the skills of struggling readers. Reading Research Quarterly. 2005;40(2):148–182. [Google Scholar]

- McMaster KL, Fuchs D, Fuchs LS, Compton DL. Responding to nonresponders: An experimental field trial of identification and intervention methods. Exceptional Children. 2005;71(4):445–463. [Google Scholar]

- National Association of State Directors of Special Education (NASDSE) Response to intervention: Policy considerations and implementation. Alexandria, VA: Author; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Reschly DJ, Tilly WD. Reform trends and system design alternatives. In: Reschly D, Tilly W, Grimes J, editors. Special education in transition. Sopris West: Longmont, CO; 1999. pp. 19–48. [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M, Yule W. The concept of specific reading retardation. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry & Allied Disciplines. 1975;16(3):181–197. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1975.tb01269.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scammacca N, Roberts G, Vaughn S, Edmonds M, Wexler J, Reutebuch CK, et al. Reading interventions for adolescent struggling readers: A metaanalysis with implications for practice. Portsmouth, NH: RMC Research Corporation, Center on Instruction; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Share DL, McGee R, Silva PA. IQ and reading progress: A test of the capacity notion of IQ. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1989;28(1):97–100. doi: 10.1097/00004583-198901000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepard L. An evaluation of the regression discrepancy method for identifying children with learning disabilities. Journal of Special Education. 1980;14:79–91. [Google Scholar]

- Shaywitz SE, Escobar MD, Shaywitz BA, Fletcher JM, Makuch R. Evidence that dyslexia may represent the lower tail of a normal distribution of reading ability. New England Journal of Medicine. 1992;326(3):145–150. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199201163260301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel LS. An evaluation of the discrepancy definition of dyslexia. Journal of Learning Disabilities. 1992;25(10):618–629. doi: 10.1177/002221949202501001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stecker PM, Fuchs LS, Fuchs D. Using curriculum-based measurement to improve student achievement: Review of research. Psychology in the Schools. 2005;42(8):795–819. [Google Scholar]

- Stuebing KK, Fletcher JM, LeDoux JM, Lyon GR, Shaywitz SE, Shaywitz BA. Validity of IQ-discrepancy classifications of reading disabilities: A meta-analysis. American Educational Research Journal. 2002;39(2):469–518. [Google Scholar]

- Swanson HL, Hoskyn M, Lee C. Interventions for students with learning disabilities: A meta-analysis of treatment outcome. New York: Guilford; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Torgesen JK. Individual differences in response to early interventions in reading: The lingering problem of treatment resisters. Learning Disabilities Research and Practice. 2000;15(1):55–64. [Google Scholar]

- Torgesen JK, Alexander AW, Wagner RK, Rashotte CA, Voeller KKS, Conway T, et al. Intensive remedial instruction for children with severe reading disabilities: Immediate and long-term outcomes from two instructional approaches. Journal of Learning Disabilities. 2001;34(1):33–58. doi: 10.1177/002221940103400104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Education. Individuals with Disabilities Improvement Act of 2004, Pub. L. 108–466. Federal register. 2004;Vol. 70(No. 118):35802–35803. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Education. Washington, DC: Author; 25th annual report to Congress on the implementation of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act. 2007

- VanDerHeyden AM, Witt JC, Gilbertson D. A multi-year evaluation of the effects of a response to intervention (RTI) model on identification of children for special education. Journal of School Psychology. 2007;45:225–256. [Google Scholar]

- Vaughn S, Fuchs LS. Redefining learning disabilities as inadequate response to instruction: The promise and potential problems. Learning Disabilities Research and Practice. 2003;18:137–146. [Google Scholar]

- Vaughn S, Levy S, Coleman M, Bos CS. Reading instruction for students with LD and EBD: A synthesis of observation studies. Journal of Special Education. 2002;36:2–13. [Google Scholar]

- Vaughn S, Linan-Thompson S. What is special about special education for students with learning disabilities? Journal of Special Education. 2003;37:140–147. [Google Scholar]

- Vaughn S, Wanzek J, Fletcher JM. Multiple tiers of intervention: A framework for prevention and identification of students with reading/learning disabilities. In: Taylor BM, Ysseldyke J, editors. Educational interventions for struggling readers. New York: Teacher’s College Press; 2007. pp. 173–196. [Google Scholar]

- Vaughn SR, Wanzek J, Woodruff AL, Linan-Thompson S. A three-tier model for preventing reading difficulties and early identification of students with reading disabilities. In: Haager DH, Vaughn S, Klingner JK, editors. Validated reading practices for three tiers of intervention. Baltimore, MD: Brookes; 2006. pp. 11–28. [Google Scholar]

- Vellutino FR, Fletcher JM, Scanlon DM, Snowling MJ. Specific reading disability (dyslexia): What have we learned in the past four decades? Journal of Child Psychiatry and Psychology. 2004;45:2–40. doi: 10.1046/j.0021-9630.2003.00305.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vellutino FR, Scanlon DM, Lyon GR. Differentiating between difficult-to-remediate and readily remediated poor readers: More evidence against the IQ-achievement discrepancy definition for reading disability. Journal of Learning Disabilities. 2000;33(3):223–238. doi: 10.1177/002221940003300302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker HM, Stiller B, Serverson HH, Feil EG, Golly A. First step to success: Intervening at the point of school entry to prevent antisocial behavior patterns. Psychology in the Schools. 1998;35:259–269. [Google Scholar]

- Wanzek J, Vaughn S. Research-based implications from extensive early reading interventions. School Psychology Review. 2007;36(4):541–561. [Google Scholar]