Abstract

The large Nuclear Mitotic Apparatus (NuMA) protein is an abundant component of interphase nuclei and an essential player in mitotic spindle assembly and maintenance. With its partner, cytoplasmic dynein, NuMA uses its cross-linking properties to tether microtubules to spindle poles. NuMA and its invertebrate homologues play a similar tethering role at the cell cortex, thereby mediating essential asymmetric divisions during development. Despite its maintenance as a nuclear component for decades after the final mitosis of many cell types (including neurons), an interphase role for NuMA remains to be established, although its structural properties implicate it as a component of a nuclear scaffold, perhaps as a central constituent of the proposed nuclear matrix.

Introduction

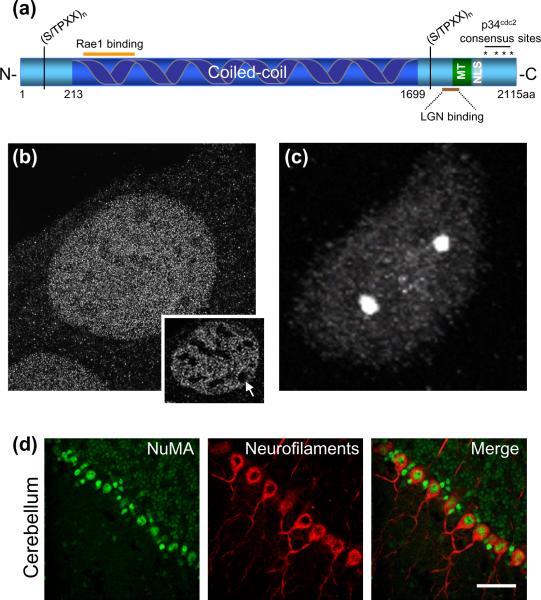

NuMA (Nuclear Mitotic Apparatus) is a high molecular weight (238 kDa) protein, first identified almost 30 years ago and aptly named by Lydersen and Pettijohn for its localization pattern to both the interphase nucleus and the mitotic spindle poles [1]. It was first described to have an exclusively nuclear localization in interphase cells but to associate with the spindle poles during mitosis (Figure 1). In the early years, NuMA was independently discovered and rediscovered by 5 groups (and given multiple names - centrophilin, SPN, and SP-H), before cloning of it provided persuasive evidence that all represented the same NuMA polypeptide [2, 3].

Figure 1.

NuMA is a component of the nucleus and the spindle poles.

(a) Schematic representation of human NuMA protein domains. Dark blue, coiled coil domain; light blue, N- and C- globular termini; gray, nuclear localization signal (NLS), residues 1971–1991 [7]; green (MT), microtubule binding domain, residues 1900–1971 [7]; brown line, LGN binding sequence (1878–1910 [7]); orange line, Rae1 binding domain, residues 325–829 [38]. S/TPXX, a DNA-binding motif found in gene regulatory proteins, occurs six times in the N- and seven times in the C- termini, respectively, of NuMA [8]. Asterisks, four p34cdc2 phosphorylation sites (threonine, 2000, 2040, 2091, serine 2072) [23]. (b) NuMA appears to fill up interphase nuclei of immortalized mouse embryonic fibroblasts. Single sections through the nucleus (inset) reveal exclusion domains (arrow). Images were acquired using structured illumination microscopy, on an OMX microscope (UC, Davis). Unpublished data. (c) NuMA is enriched at the spindle poles of mitotic HeLa cells (image acquired using an Olympus FV1000 spectral deconvolution confocal microscope). Unpublished data. (d) NuMA is expressed in nuclei of post-mitotic neurons. Immunofluorescence staining of frozen cerebellar sections from an adult C57/B6 mouse, with antibodies against NuMA (green) and unphosphorylated neurofilaments (red). Images in (d), courtesy of Dr. Alain Silk, unpublished data. Scale bar, 50μm.

The NuMA molecule is comprised of globular head and tail domains separated by a 1500 amino acid discontinuous coiled-coil [4]. The C-terminus contains a nuclear localization signal (NLS) [5] and a 100 amino acid stretch that directly binds and bundles microtubules [6, 7]. In addition, both globular domains contain several S/TPXX motifs, sequences found in gene regulatory proteins and thought to bind DNA [8] (Figure 1). siRNA-mediated depletion [9] and knockout strategies in mice [10], have implicated NuMA as an essential protein. Taken together, these features make NuMA an excellent candidate for an important structural component both in the nucleus and at spindle poles (Figure 1). We review here NuMA's role in tethering the bulk of spindle microtubules to the spindle poles, the direct role NuMA, along with LGN and Gα plays in spindle positioning and asymmetric cell division, and a possible, still unresolved, role as a nuclear scaffold.

NuMA: tethering spindle microtubules to their poles

Once every cell cycle, the genome is segregated via the mitotic spindle, a dynamic structure that assembles at the onset of mitosis and disassembles at mitotic exit. In its simplest form, the mitotic spindle consists of two complex, proteinaceous poles, coincident with centrosomes, which nucleate the growth and assembly of microtubules. The events that initiate spindle assembly in many eukaryotic cells coincide with nuclear envelope breakdown and include not only centrosome-mediated nucleation of new mitotic microtubules, but also minus end microtubule focusing and anchoring at spindle poles. While the minus ends of spindle microtubules cluster together at the spindle poles, their plus ends grow towards the cell equator in search of capture by kinetochores. Use of immunoelectron microscopy revealed NuMA to reside in a region adjacent to the centrosome, but not directly associated with it [11, 12, 13]. This finding hinted at what is now widely recognized to be true: NuMA plays roles in spindle maintenance by physically tethering microtubules to centrosomes (centrosome-dependent) and by focusing spindle microtubules at the poles (centrosome-independent) (see below).

The significance of NuMA's distribution with the mitotic spindle poles was initially addressed by microinjection of NuMA inhibitory antibodies into mammalian cells at various mitotic stages [14] and expression of amino and carboxy terminal truncation mutants [15]. Both approaches resulted in aberrant spindles. While a series of detailed studies initially concluded that NuMA may be required for completion of mitosis and post-mitotic nuclear reassembly [3, 16], it is now recognized that all of these phenotypes simply reflect NuMA's essential role in tethering spindle microtubules to each pole [17]. Such tethering function was initially characterized [17, 18] by NuMA immunodepletion from Xenopus extracts that can assemble bi-polar spindles and align chromosomes following addition of sperm nuclei, chromosome replication and passage into the subsequent mitosis.

Furthermore, depletion of NuMA from Xenopus extracts resulted in pole fragmentation and/ or dissociation of the centrosome from already assembled spindles, followed by splaying of the remaining spindle microtubules [17, 19]. This defect was rescued (in part) by reconstitution with purified NuMA, indicating a direct role in spindle pole function [17] and suggesting that at least a subset of spindle microtubules requires NuMA for proper affinity to the poles. NuMA antibody addition to preformed bi-polar spindles resulted in the remarkable finding that despite retention of a bi-polar spindle, the centrosomes were dissociated and the polar microtubules were now splayed, rather than focused to a point [20]. With the discovery that DNA-coated beads stimulate microtubule assembly around them independent of centrosomes [21], depletion was used to demonstrate once again that NuMA was essential for zippering those microtubules into a pair of focused poles [20]. Importantly, a recent report [10] extended these findings in a mammalian whole-cell system by construction and analysis of a conditional loss of mitotic function allele of NuMA in mice and cultured primary mouse cells. This study demonstrated that although NuMA functions redundantly with centrosomes in initial mitotic spindle assembly, its tethering function is essential for spindle maintenance [10].

A role for NuMA at the spindle poles reflects one, or both, of two mechanisms for forming stabilizing crossbridges between spindle pole microtubules. First, a putative structural “spindle pole matrix” built by active dynein-mediated transport of NuMA to, and deposition at, poles is responsible for tethering microtubule minus ends via the microtubule binding sites on each NuMA molecule. In this model, dimeric or oligomeric NuMA complexes provide the tethering matrix. The other mechanism for dynamic focusing of microtubules at their minus ends is mediated by a NuMA-dynein (Table 1; Box1) complex that utilizes both NuMA and dynein microtubule binding sites for transient association with microtubule tracks. Both mechanisms are likely to make meaningful contributions to pole stability.

Table 1.

Summary of NuMA interacting proteins

| Stage | Interacting partner | NuMA interacting domain | Comments | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interphase | Importin | NLS in C-terminus | RanGTP/RCC1 dependent | [31] |

| GAS41 (Glioma-Amplified-Sequence 41) | C-terminal coiled-coil | Ubiquitous, essential transcription factor amplified in human gliomas | [78] | |

| MARs (Matrix Associated Regions) | S/TPXX motifs in N- and C-termini | 300–1,000bp DNA regions, 70% A+T rich; transcriptional enhancer activity | [8] | |

| Mitosis | Dynein/dynactin | Minus end directed motor | [17] | |

| Microtubules | Residues 1900–1971 in C-terminus | [7] | ||

| Rae1 | Residues 325–829 in N-terminus of coiled-coil | Binds microtubules; role with NuMA in microtubule bundling | [38] | |

| Emi1 | Binds NuMA/dynein complex | APC inhibitor, part of END (Emi1, NuMA, Dynein) complex | [28] | |

| LGN | Residues 1878–1910 in C-terminus | Negative regulator of NuMA function; competes with microtubules for binding to overlapping domains in NuMA C-terminus | [7, 45] | |

| Asymmetric division | LGNa, GPR1/2b, Pinsc | LGN binds NuMA and Gα; Pins binds Mud and Gαi | [42, 52, 44] | |

| Dynein | Minus end directed motor | [55] |

– human, C. elegans, Drosophila melanogaster homologs, respectively

– human, C. elegans, Drosophila melanogaster homologs, respectively

– human, C. elegans, Drosophila melanogaster homologs, respectively

The sum of these findings established that most spindle microtubules are tethered to a putative spindle pole matrix and not always directly attached to centrosomes. This counterintuitive point has not been widely appreciated, but was implicit in the earlier demonstrations by three dimensional reconstruction of serially sectioned spindles: with each microtubule 25 nm in diameter, considerations of steric hindrance between microtubules revealed that only about a quarter of the microtubule minus ends in a mammalian half spindle can be directly embedded into the (~500 nm) centrosome [22]. Taken together, the findings from cell-free and whole-cell systems suggest a model whereby NuMA, in complex with dynein and dynactin, the dynein activator/ processivity complex (Box 1), provides an essential stabilizing structure for the microtubule-centrosome interaction at the spindle pole. In its absence, centrosomes lose their attachment to kinetochore fibers and spindle poles are unfocused.

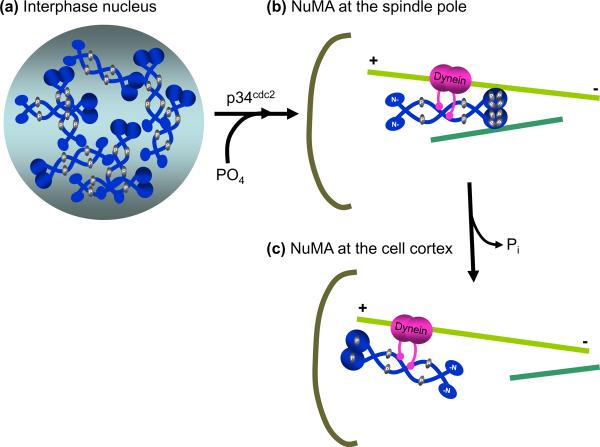

NuMA phosphorylation/ dephosphorylation at mitotic entry/ exit

Concomitant with nuclear envelope breakdown, NuMA is hyperphosphorylated by p34cdc2 [23] and relocalizes via a dynein-mediated mechanism [17] from the former nuclear volume to the spindle poles where it remains until anaphase [24]. NuMA's phosphorylation at four putative p34cdc2 sites has been proposed to regulate its interaction with dynein and therefore its dynein-dependent spindle pole localization [23–26]. Mutation of any of the four phosphorylated residues within this consensus sequence results in failure of NuMA to associate with the spindle poles and its targeting instead to the plasma membrane [23]. NuMA phosphorylation is thought to increase its solubility which may be necessary for relocation to poles [26]. A plausible model is that the mitotically acquired solubility coupled both with the microtubule bundling activity conferred by NuMA's microtubule binding domain [6] and its dimeric nature [27] allow it to provide both structure and flexibility to the spindle pole (Figure 2).

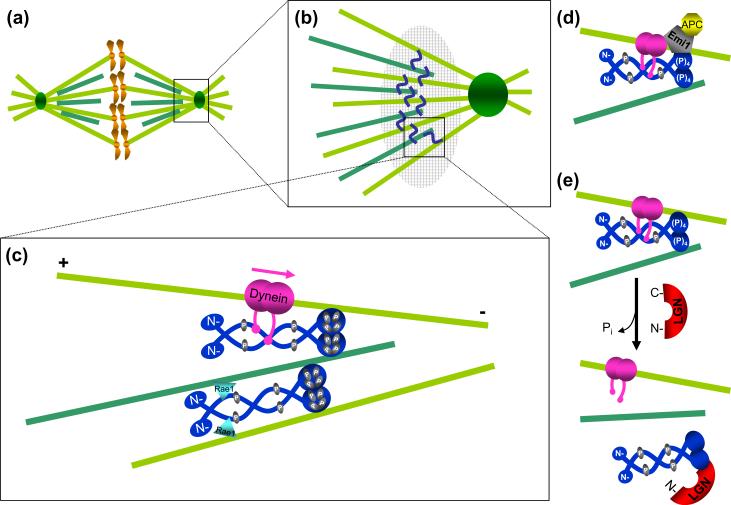

Figure 2.

NuMA functions at spindle poles to bundle and tether microtubules. (a) Schematic of the mitotic spindle, representing kinetochore (light green) and non-kinetochore (dark green) microtubules. The spindle pole (square box) is enlarged in (b). NuMA (blue squiggle) cross-links kinetochore and non-kinetochore microtubules at the spindle pole. NuMA containing complexes involved in microtubule linkage at the spindle poles form a structure equivalent to a “spindle pole matrix” (large hatched oval). (c) Proteins interacting with NuMA at spindle poles (enlarged square box from (b)). During nuclear breakdown, NuMA is phosphorylated (yellow) at four putative p34cdc2 sites (threonine 2000, 2040, 2091, serine 2072) [23, 25]. Mitotically phosphorylated NuMA associates with dynein (pink), which carries it in a minus-end directed fashion (pink arrow) and deposits it at spindle poles where it functions in spindle maintenance via microtubule tethering [20]. A NuMA dimer (dark blue, top) cross-links microtubules through interactions mediated by its C-terminal microtubule binding domain and the associated dynein (pink) [6, 7]. Rae1, a messenger RNA transport protein (blue triangle), may also mediate binding of the NuMA N-termini to microtubules [38], thus transiently generating a higher level of parallel microtubule bundling (bottom microtubules). (d) Emi1 (gray), an inhibitor of Cdc20 dependent activation of the anaphase promoting complex (APC), has been proposed to exist in a complex with dynein and NuMA prior to anaphase [28], as a means of sequestering APCCdc20 (yellow) away from the general cytoplasm. (e) A possible mechanism for NuMA dissociation from microtubules. LGN (red), by competing with microtubules for NuMA binding, acts as a negative regulator of NuMA bundling [7] and may be responsible for the relocalization of a NuMA subset from the spindle pole to the cell cortex.

In normal mitosis, NuMA remains associated with the spindle poles until anaphase, when silencing of the mitotic checkpoint (also known as the spindle assembly checkpoint) and ubiquitination of cyclin B and securin by the anaphase promoting complex (APC) results in their proteasome-mediated degradation. Prior to mitotic exit Emi1 – an APC/C inhibitor – is sequestered at the spindle poles as part of a somewhat controversial complex with NuMA and dynein (named the END complex, for Emi, NuMA, dynein) [28, 29]. If this is correct (Figure 2), in addition to its structural role, NuMA may have a regulatory function in mitotic progression by sequestering mitotic checkpoint components (i.e., Emi1). Finally, Cdk1 inactivation from loss of cyclin B leads to dephosphorylation of NuMA, apparently disrupting its association with dynein [24]. Therefore, NuMA may act as part of a feedback loop that ensures its function as a dynein-associated tether during mitosis as well as its APC-dependent release from the complex at the end of mitosis.

NuMA linked to nuclear transport components in interphase and mitosis

Several early experiments suggested that components of the nuclear transport machinery may be involved in mitotic spindle assembly and structure, and implicated NuMA in these processes. The monomeric GTP binding protein, Ran, functions in protein and RNA transport into and out of the nucleus during interphase [30]. Importins bind the nuclear localization sequences (NLS) of proteins to be imported into the nucleus and RanGTP mediates the dissociation of cargo from importins following import [31]. The GTP exchange factor for Ran is RCC1, which is exclusively bound to chromatin throughout the cell cycle. During mitosis, the RCC1 activity generates a RanGTP concentration gradient extending away from chromosomes that at least in some contexts plays a key role in microtubule polymerization and mitotic spindle assembly [32, 33]. This gradient has been directly visualized by a clever fluorescence resonance energy transfer approach [34, 35].

A key insight was that analogous to their interphase intranuclear function in mitosis, importins would bind to and inactivate microtubule assembly factors with an NLS, except when directly adjacent to a chromosome where these interactions would be abrogated by high concentrations of RanGTP [31, 36, 37]. The liberated factors could now mediate centrosome-independent microtubule polymerization and spindle assembly. Several such microtubule assembly factors have been identified, including TPX2, a microtubule-associated protein that targets the motor protein Xklp2 to microtubules [36], and NuMA [31, 37]. Indeed, depletion, fractionation and complementation experiments in Xenopus egg extracts revealed a functional association between importin-α/β, NuMA and Ran (Table 1) [31, 37]. This finding provided a mechanism in early mitosis whereby importins, by binding to the NuMA NLS, sequester NuMA to prevent its microtubule association except adjacent to chromosomes where the RanGTP concentration is highest.

Another component implicated in nuclear transport and with an additional mitotic role is Rae1, a messenger RNA export factor. When depleted or over-expressed, Rae1 causes spindle multipolarity, which can be rescued by over-expression or depletion of NuMA, respectively [38]. While Rae1 was initially implicated as a component of nuclear export [39] and subsequently as a Bub3-like contributor to the kinetochore-derived mitotic checkpoint [40], it also binds both to microtubules and the N-terminal coiled-coil of NuMA. Like NuMA, Rae1 functions in the importin-β/ RanGTP pathway [41] and may thus provide an added level of microtubule crosslinking so as to result in transient parallel cross-linked microtubule fibers (Figure 2) beginning in the vicinity chromosomes.

Spindle positioning and asymmetric cell division

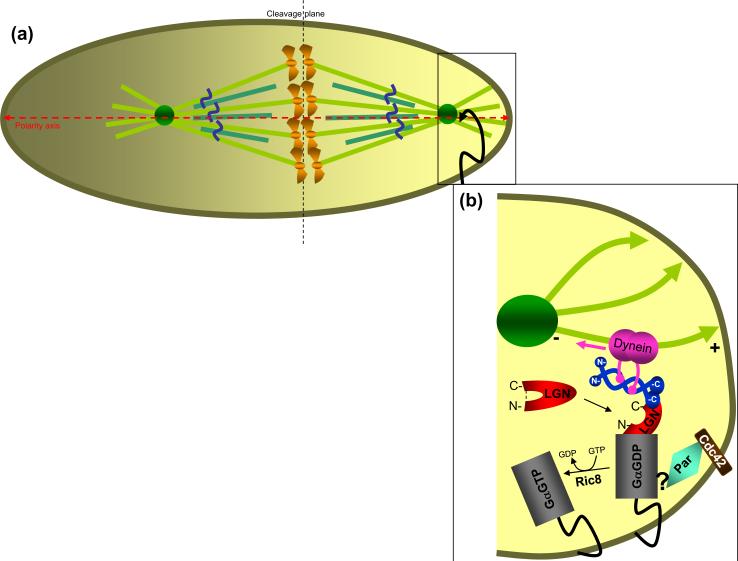

A recent insight for NuMA in spindle pole tethering is its role in asymmetric cell division which is relevant to the determination of cell fate during development and to the specification of stem cell self-renewal versus differentiation. During asymmetric cell division, cleavage must occur such that protein components are distributed unequally to the two daughter cells. The main geometrical prerequisite for asymmetric cleavage plane determination is the alignment of the mitotic spindle toward one pole of the polarity axis (Figure 3). For this, an emerging realization is that NuMA functions not just at the spindle poles but that a subset is preferentially recruited only to one part of the cell cortex, where it mediates spindle anchoring. Preferential deposition of anchoring components (i.e., adherens junctions/ Cdc42) at one end of the mother cell followed by capture of astral microtubules from the closest spindle pole yields asymmetric spindle positioning [42]. Evidence from analysis of NuMA orthologs and their associated protein complexes (Table 1) in humans (NuMA/ LGN/ Gα) [43], the nematode C. elegans (LIN-5/ GPR-1/2/ Gα) [44] and the fruitfly Drosophila melanogaster (Mud/ Pins/ Gα) [45] has revealed an evolutionarily conserved mechanism whereby polarized, LGN/ Gα-dependent NuMA localization at the cell cortex coupled to the dynein-mediated pulling of the spindle results in asymmetric spindle orientation.

Figure 3.

Spindle positioning and asymmetric cell division. (a) During asymmetric cell division the mitotic spindle is positioned along the polarity axis (red dashed horizontal line) and tethered to one pole of the cell (square box), thus establishing an off center cleavage plane (dashed vertical line). (b) Protein complexes involved in spindle orientation (enlarged square box from (a)). External cues, an adherens junctions/ Cdc42 complex (brown) and Par (light blue) determine mother cell polarity [86, 87]. The Par complex recruits the GDP-bound, myristoylated Gα subunit of the trimeric G protein, Gi, and this interaction is mediated by a poorly described protein complex [44]. Normally, LGN exists in the cytoplasm in a closed conformation (red, unbound). Dual binding of NuMA and Gα at its C- and N-termini, respectively, switches LGN to an open conformation (red, bound). These interactions ensure recruitment of NuMA to specific sites at the cell cortex [42]. Ric8 (Resistance to inhibitors of cholinesterase 8) is a guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) for Gαi-GDP [88, 89]. The Ric8-mediated release of Gαi-GTP results in dissociation of the LGN/ NuMA/ Gα complex.

Asymmetric positioning requires Par proteins (Partitioning defective) that dictate the polarized localization of receptor-independent trimeric G-proteins and their regulators (LGN/ GPR-1/2/ Pins) which in turn recruit cortical NuMA to the complex [46] (Figure 3). Disruption of Gα and either GPR-1/2 or Pins by protein depletion or inactivation results in alignment defects in C. elegans [47] and Drosophila [48, 49], respectively, thus implicating Gα and its regulators as key components of the spindle positioning pathway [50, 51]. Initial hints of NuMA involvement in asymmetric cell division came from studies of its Drosophila homolog, Mud (Mushroom body defect). mud mutant flies display abnormal asymmetric neuroblast division due to failure to align the spindle with the polarity axis [52, 53].

The human Gα regulator, LGN, is a member of the LGN/ Pins family (reviewed in 44) and a key regulator of mitotic spindle assembly [7, 54] and spindle movement [42]. In interphase cells LGN is cytoplasmic, while in mitosis it is found both at spindle poles and at the cell cortex [45]. Its spindle pole localization is mediated by an interaction with a domain in the C-terminus of NuMA that overlaps the microtubule binding motif. By virtue of competitive binding between microtubules and LGN for NuMA, LGN acts as a negative regulator of spindle assembly [7, 45]. This scenario is attractive since a balance between stabilizing (i.e., microtubule cross-linking) and destabilizing forces (i.e., competitive binding of LGN to the microtubule binding site in NuMA) may be necessary for the dynamic nature of the mitotic spindle pole. In addition, LGN binding to spindle pole-associated NuMA may be necessary for liberating a subset of NuMA molecules for their role at the cell cortex in spindle positioning. This interaction is likely to be dependent on phosphorylation since treatment of in vitro assembled asters with staurosporin, a global kinase inhibitor, prevented LGN binding to NuMA and its displacement from microtubules [54].

LGN's cortical enrichment has been attributed to its interaction with the plasma membrane-anchored Gα subunit [42, 49]. LGN inhibits itself through interaction of its N-and C-termini in a hairpin-like structure, and which can be activated by binding of Gα and NuMA at its N- and C-termini, respectively [42]. This dual interaction results in the LGN-mediated recruitment of NuMA to the plasma membrane. Taking this into consideration, a likely scenario is that specific alterations in NuMA phosphorylation at one or more sites may provide a switch between symmetric and asymmetric division by regulating its LGN-dependent re-localization from the spindle poles to the cell cortex in mitosis.

The mechanism whereby the spindle becomes anchored to the plasma membrane remained unclear until dynein was identified in C. elegans as the factor responsible for providing the cortical pulling force on astral microtubules [55, 56]. Depletion of either the dynein heavy or light chains resulted in spindle orientation defects and abnormal division in one- and two-cell stage embryos, similar to the defects caused by deletion/inactivation of Gα [50, 57]. Since NuMA and its C. elegans homolog, LIN-5, are known to interact with dynein [17, 55, 56] and the G-protein regulators LGN and GPR1/2 [7, 42, 55], respectively, a model soon emerged whereby NuMA was implicated as the link between the cortical polarity determinants and the force generator, dynein [55] (Figure 3). According to this model, in C. elegans the membrane anchored complex of LIN-5, GPR-1/2, and Gα pulls one spindle pole towards the cortex by a dynein-dependent mechanism and thereby asymmetrically positions the spindle [55]. Although not as well established, similar complexes are believed to be at play in humans and Drosophila (reviewed in 44).

An analogous pathway functions in symmetric division to ensure spindle orientation and oscillatory movements. While in multiple nonpolarized cell types the majority of NuMA functions at the spindle pole, a pool can be detected at the cortex in association with LGN [42]. The Gα/ LGN/ NuMA/ dynein complex effects spindle capture and positioning, which in the absence of external cues and Par-dependent polarization, is symmetric.

NuMA as a nuclear structural component

The extensive DNA content of the cell is organized into linear chromosomes (~1 m initial length) that are packaged tightly into the nuclear space (typically ~10 μm in diameter) as chromatin, along with large enzymatic complexes involved in DNA replication, repair and multiple levels of gene expression. Furthermore, nuclear subcompartments such as nucleoli, speckles and PML bodies have been equated to “nuclear organelles” based on the defined set of proteins localized to these structures [58, 59]. A putative “nuclear matrix” may be responsible for maintaining genomic order as well as the functional identity of these structures.

The idea of a “nuclear matrix,” defined as an insoluble, three dimensional network of structural proteins that remains in the nucleus following removal of membrane and chromatin, was initially proposed by Berezney and Coffey [60] and then again by Nickerson and Penman [61, 62], who suggested it to provide a structural framework and compartmentalization inside the nucleus, analogous to the cytoplasmic cytoskeleton.

It should be recognized that despite its attractiveness, even 35 years after the earliest reports, molecular components of such a nuclear matrix have been elusive. Maintained in most differentiated, post-mitotic nuclei (e.g., in motor neurons as illustrated in Figure 1), NuMA is perhaps the most attractive candidate for a structural constituent of a nuclear scaffold [2, 63, 64]. While it is possible that NuMA's nuclear localization in cycling cells is merely a way of sequestering it away from cytoplasmic microtubules, an alternative scenario suggests that NuMA may play an important role in genome reorganization following each mitosis cycle in dividing cells. Furthermore, its maintenance in post-mitotic nuclei, years after the final division suggests an active, non-mitotic role in differentiated cells. Other proposed nuclear structural components include nuclear lamins [65, 66] and membrane-associated lamin interacting proteins [67]. To be sure, the peripherally localized lamins have affinity for DNA, chromatin and histones [68], and these interactions have been implicated in gene silencing by anchoring heterochromatin to the nuclear periphery [69]. However, these interactions seem insufficient to provide the high degree of internal nuclear localization.

Several lines of evidence suggest that NuMA may serve as a structural component of nuclei: 1) it contains a large coiled-coil domain strongly suggestive of assembly into filaments; 2) it forms parallel coiled-coil dimers mediated by two C-termini both in vivo and in vitro that are approximately 200 nm in length as seen by electron microscopy [70] as well as 3) higher order multi-arm structures [70]; 4) endogenous NuMA is highly abundant, at an estimated 106 copies per nucleus [2, 71] and occupies a majority of the nuclear volume; and 5) a relationship between nuclear shape and NuMA levels was proposed, whereby NuMA is undetectable in non-spherical nuclei [64]. Most importantly, immunogold electron microscopy has localized NuMA to a subset of nuclear core filaments in extracted, resinless sections [72]. Although far from being accepted as a component of the putative “nuclear matrix,” these features make NuMA an attractive candidate as an essential structural component of post-mitotic nuclei.

NuMA and genomic organization

In the late 1800s, the great German cytologist Theodore Boveri proposed a non-random chromosome arrangement inside the nucleus [73] and the existence of chromosome territories was confirmed in the 1970s (reviewed in 74). Following from these early ideas, it has been proposed that the organization of DNA in the nucleus has cell and tissue specific determinants and that differential organization contributes to tissue specific gene expression [75]. Consistent with a role in genomic organization, tightly regulated NuMA levels have been proposed to be essential for the creation of chromosome domains either by organizing chromatin [76], by interacting with specific DNA domains called matrix attachment regions (MARs) [77, 8] or by simply providing a substrate for intranuclear processes (Table 1). Yeast two-hybrid studies suggested an interaction between NuMA and GAS41 (glioma-amplified-sequence 41) [78], an ubiquitous, essential transcription factor amplified in human gliomas [9]. GAS41 is a homolog of human myeloid/ lymphoid or mixed lineage leukemia AF9 (a transcription factor) and ENL (a chromatin remodeling complex) and interacts with INI1 (Integrase Initiator 1), the human homolog of the yeast SNF5, a component of the chromatin remodeling complex, SWI/SNF [79]. Furthermore, MARs are 300–1000bp DNA regions, 70% A+T rich and have been described as sequences that “fasten” chromatin to the nuclear matrix. They have been shown to reside near cis-regulatory elements and have transcriptional enhancer activity [8]. The described in vitro interactions between the DNA binding S/TPXX motifs in the N- and C- termini of NuMA and MARs suggests a possible NuMA affinity for genomic regulatory regions. A role for NuMA as a structural substrate for nuclear processes is proposed by the observation that increased expression of the full length NuMA generates a filamentous scaffold that fills nuclei [70], while overexpression of truncated NuMA constructs leads to relocation of nucleoli, DNA and histone H1 to the nuclear rim [80]. These spatial rearrangements are likely to have consequences on multiple levels of gene expression.

Relevant to the link between nuclear structure and genome organization, two models have been proposed for genomic organization: 1) a deterministic model in which structure dictates function and 2) a self-organizing model whereby dynamic interactions among chromosomes, protein complexes and the nuclear periphery result in a specific genomic configuration as a consequence of the sum of all functions [81]. The non-random chromosome distribution within the nucleus is likely to be important to the prevention of physical interaction among chromosomes, since close apposition between them may lead to genomic instability due to fusions and translocations [82]. Conversely, distant DNA sequences have been shown to interact by virtue of chromosome looping to provide an added level of gene regulation [83] and it is likely that their physical interaction is mediated by an underlying structural framework such as a “nuclear matrix.”

Furthermore, a framework such as the nuclear matrix may function to integrate mechanical as well as biochemical signals from the extracellular matrix to effect genomic order and gene activity [84]. Such complex signaling pathways may have roles in development, differentiation, normal cell function, and normal aging and if so, errors in these pathways are likely to contribute to disease. Indeed, even in unicellular eukaryotes (e.g., fission yeast) a set of nuclear membrane proteins apparently interact with centromeric chromatin and a nuclear scaffold to integrate cytoplasmic forces imposed on the nuclear envelope [85]. In the absence of these interactions, nuclear deformation is prominent and may lead to displacement and subsequent deregulation of intranuclear events. Similar mechanisms are highly likely to be at play in higher eukaryotes and may be required to maintain subnuclear order. It is conceivable that a structure like the NuMA-positive nuclear core filaments [72] could provide the strength required to withstand disruptive forces.

It seems likely, at least to us, that an underlying, NuMA-based scaffold may support the dynamic organization of the genome, while at the same time providing structure to the post-mitotic nucleus over the long term. An experimental test for such roles for NuMA in intranuclear structure has not been reported – and is long overdue.

Box 1. Dynein and dynactin.

Cytoplasminc dynein is a microtubule-associated molecular motor that uses energy derived from ATP hydrolysis to move in a minus end-directed fashion, that is, towards the centrosomal area of the cell. Dynein is a large complex of multiple polypetides: two identical large heavy chains which provide ATPase activity and microtubule binding, two non-catalytic intermediate chains thought to be responsible for cargo anchoring and several light intermediate and light chains which bind dynein adaptor proteins. The non-catalytic subunits mediate interaction with various adaptors, one of which, dynactin, is a large, multi-subunit complex that targets dynein to subcellular locations and links it to various cargoes. Intracellular functions of the dynein-dynactin complex include vesicular and organelle transport, positioning of intracellular organelles (i.e., the nucleus, the centrosome, the Golgi apparatus), as well as various aspects of mitotic spindle dynamics (i.e., chromosome alignment, transport of spindle assembly checkpoint components, delivery and deposition of NuMA at the spindle poles) (Reviewed in [90]).

Figure 4.

References

- 1.Lydersen BK, Pettijohn DE. Human-specific nuclear protein that associates with the polar region of the mitotic apparatus: distribution in a human/hamster hybrid cell. Cell. 1980;22:489–499. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(80)90359-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Compton DA, et al. Primary structure of NuMA, an intranuclear protein that defines a novel pathway for segregation of proteins at mitosis. J Cell Biol. 1992;116:1395–1408. doi: 10.1083/jcb.116.6.1395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kallajoki M, et al. Microinjection of a monoclonal antibody against SPN antigen, now identified by peptide sequences as the NuMA protein, induces micronuclei in PtK2 cells. J Cell Sci. 1993;104(Pt 1):139–150. doi: 10.1242/jcs.104.1.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang CH, et al. NuMA: an unusually long coiled-coil related protein in the mammalian nucleus. J Cell Biol. 1992;116:1303–1317. doi: 10.1083/jcb.116.6.1303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gueth-Hallonet C, et al. NuMA: a bipartite nuclear location signal and other functional properties of the tail domain. Exp Cell Res. 1996;225:207–218. doi: 10.1006/excr.1996.0171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haren L, Merdes A. Direct binding of NuMA to tubulin is mediated by a novel sequence motif in the tail domain that bundles and stabilizes microtubules. J Cell Sci. 2002;115:1815–1824. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.9.1815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Du Q, et al. LGN blocks the ability of NuMA to bind and stabilize microtubules. A mechanism for mitotic spindle assembly regulation. Curr Biol. 2002;12:1928–1933. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)01298-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Luderus ME, et al. Binding of matrix attachment regions to lamin polymers involves single-stranded regions and the minor groove. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:6297–6305. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.9.6297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harborth J, et al. Identification of essential genes in cultured mammalian cells using small interfering RNAs. J Cell Sci. 2001;114:4557–4565. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.24.4557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Silk AD, et al. Requirements for NuMA in maintenance and establishment of mammalian spindle poles. J Cell Biol. 2009;184:677–690. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200810091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tousson A, et al. Centrophilin: a novel mitotic spindle protein involved in microtubule nucleation. J Cell Biol. 1991;112:427–440. doi: 10.1083/jcb.112.3.427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maekawa T, et al. Identification of a minus end-specific microtubule-associated protein located at the mitotic poles in cultured mammalian cells. Eur J Cell Biol. 1991;54:255–267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dionne MA, et al. NuMA is a component of an insoluble matrix at mitotic spindle poles. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 1999;42:189–203. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0169(1999)42:3<189::AID-CM3>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang CH, Snyder M. The nuclear-mitotic apparatus protein is important in the establishment and maintenance of the bipolar mitotic spindle apparatus. Mol Biol Cell. 1992;3:1259–1267. doi: 10.1091/mbc.3.11.1259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Compton DA, Cleveland DW. NuMA is required for the proper completion of mitosis. J Cell Biol. 1993;120:947–957. doi: 10.1083/jcb.120.4.947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cleveland DW. NuMA: a protein involved in nuclear structure, spindle assembly, and nuclear re-formation. Trends Cell Biol. 1995;5:60–64. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(00)88947-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Merdes A, et al. A complex of NuMA and cytoplasmic dynein is essential for mitotic spindle assembly. Cell. 1996;87:447–458. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81365-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gaglio T, et al. NuMA is required for the organization of microtubules into aster-like mitotic arrays. J Cell Biol. 1995;131:693–708. doi: 10.1083/jcb.131.3.693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Merdes A, Cleveland DW. Pathways of spindle pole formation: different mechanisms; conserved components. J Cell Biol. 1997;138:953–956. doi: 10.1083/jcb.138.5.953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Merdes A, et al. Formation of spindle poles by dynein/dynactin-dependent transport of NuMA. J Cell Biol. 2000;149:851–862. doi: 10.1083/jcb.149.4.851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heald R, et al. Self-organization of microtubules into bipolar spindles around artificial chromosomes in Xenopus egg extracts. Nature. 1996;382:420–425. doi: 10.1038/382420a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mastronarde DN, et al. Interpolar spindle microtubules in PTK cells. J Cell Biol. 1993;123:1475–1489. doi: 10.1083/jcb.123.6.1475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Compton DA, Luo C. Mutation of the predicted p34cdc2 phosphorylation sites in NuMA impair the assembly of the mitotic spindle and block mitosis. J Cell Sci. 1995;108(Pt 2):621–633. doi: 10.1242/jcs.108.2.621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gehmlich K, et al. Cyclin B degradation leads to NuMA release from dynein/dynactin and from spindle poles. EMBO Rep. 2004;5:97–103. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sparks CA, et al. Phosphorylation of NUMA occurs during nuclear breakdown and not mitotic spindle assembly. J Cell Sci. 1995;108(Pt 11):3389–3396. doi: 10.1242/jcs.108.11.3389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saredi A, et al. Phosphorylation regulates the assembly of NuMA in a mammalian mitotic extract. J Cell Sci. 1997;110(Pt 11):1287–1297. doi: 10.1242/jcs.110.11.1287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harborth J, et al. Epitope mapping and direct visualization of the parallel, in-register arrangement of the double-stranded coiled-coil in the NuMA protein. Embo J. 1995;14:2447–2460. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07242.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ban KH, et al. The END network couples spindle pole assembly to inhibition of the anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome in early mitosis. Dev Cell. 2007;13:29–42. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reimann JD, et al. Emi1 is a mitotic regulator that interacts with Cdc20 and inhibits the anaphase promoting complex. Cell. 2001;105:645–655. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00361-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moore MS, Blobel G. The GTP-binding protein Ran/TC4 is required for protein import into the nucleus. Nature. 1993;365:661–663. doi: 10.1038/365661a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nachury MV, et al. Importin beta is a mitotic target of the small GTPase Ran in spindle assembly. Cell. 2001;104:95–106. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00194-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wilde A, Zheng Y. Stimulation of microtubule aster formation and spindle assembly by the small GTPase Ran. Science. 1999;284:1359–1362. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5418.1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ohba T, et al. Self-organization of microtubule asters induced in Xenopus egg extracts by GTP-bound Ran. Science. 1999;284:1356–1358. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5418.1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Carazo-Salas RE, et al. Generation of GTP-bound Ran by RCC1 is required for chromatin-induced mitotic spindle formation. Nature. 1999;400:178–181. doi: 10.1038/22133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kalab P, et al. Visualization of a Ran-GTP gradient in interphase and mitotic Xenopus egg extracts. Science. 2002;295:2452–2456. doi: 10.1126/science.1068798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gruss OJ, et al. Ran induces spindle assembly by reversing the inhibitory effect of importin alpha on TPX2 activity. Cell. 2001;104:83–93. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00193-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wiese C, et al. Role of importin-beta in coupling Ran to downstream targets in microtubule assembly. Science. 2001;291:653–656. doi: 10.1126/science.1057661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wong RW, et al. Rae1 interaction with NuMA is required for bipolar spindle formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:19783–19787. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609582104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Murphy R, et al. GLE2, a Saccharomyces cerevisiae homologue of the Schizosaccharomyces pombe export factor RAE1, is required for nuclear pore complex structure and function. Mol Biol Cell. 1996;7:1921–1937. doi: 10.1091/mbc.7.12.1921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Babu JR, et al. Rae1 is an essential mitotic checkpoint regulator that cooperates with Bub3 to prevent chromosome missegregation. J Cell Biol. 2003;160:341–353. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200211048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Blower MD, et al. A Rae1-containing ribonucleoprotein complex is required for mitotic spindle assembly. Cell. 2005;121:223–234. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Du Q, Macara IG. Mammalian Pins is a conformational switch that links NuMA to heterotrimeric G proteins. Cell. 2004;119:503–516. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lechler T, Fuchs E. Asymmetric cell divisions promote stratification and differentiation of mammalian skin. Nature. 2005;437:275–280. doi: 10.1038/nature03922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Siller KH, Doe CQ. Spindle orientation during asymmetric cell division. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:365–374. doi: 10.1038/ncb0409-365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Du Q, et al. A mammalian Partner of inscuteable binds NuMA and regulates mitotic spindle organization. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:1069–1075. doi: 10.1038/ncb1201-1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Izumi Y, et al. Drosophila Pins-binding protein Mud regulates spindle-polarity coupling and centrosome organization. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:586–593. doi: 10.1038/ncb1409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gotta M, et al. Asymmetrically distributed C. elegans homologs of AGS3/PINS control spindle position in the early embryo. Curr Biol. 2003;13:1029–1037. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00371-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Siegrist SE, Doe CQ. Microtubule-induced Pins/Galphai cortical polarity in Drosophila neuroblasts. Cell. 2005;123:1323–1335. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.09.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nipper RW, et al. Galphai generates multiple Pins activation states to link cortical polarity and spindle orientation in Drosophila neuroblasts. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:14306–14311. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701812104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gotta M, Ahringer J. Distinct roles for Galpha and Gbetagamma in regulating spindle position and orientation in Caenorhabditis elegans embryos. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:297–300. doi: 10.1038/35060092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fuse N, et al. Heterotrimeric G proteins regulate daughter cell size asymmetry in Drosophila neuroblast divisions. Curr Biol. 2003;13:947–954. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00334-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Siller KH, et al. The NuMA-related Mud protein binds Pins and regulates spindle orientation in Drosophila neuroblasts. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:594–600. doi: 10.1038/ncb1412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bowman SK, et al. The Drosophila NuMA Homolog Mud regulates spindle orientation in asymmetric cell division. Dev Cell. 2006;10:731–742. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kisurina-Evgenieva O, et al. Multiple mechanisms regulate NuMA dynamics at spindle poles. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:6391–6400. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nguyen-Ngoc T, et al. Coupling of cortical dynein and G alpha proteins mediates spindle positioning in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:1294–1302. doi: 10.1038/ncb1649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Couwenbergs C, et al. Heterotrimeric G protein signaling functions with dynein to promote spindle positioning in C. elegans. J Cell Biol. 2007;179:15–22. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200707085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Colombo K, et al. Translation of polarity cues into asymmetric spindle positioning in Caenorhabditis elegans embryos. Science. 2003;300:1957–1961. doi: 10.1126/science.1084146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dellaire G, Bazett-Jones DP. PML nuclear bodies: dynamic sensors of DNA damage and cellular stress. Bioessays. 2004;26:963–977. doi: 10.1002/bies.20089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lamond AI, Spector DL. Nuclear speckles: a model for nuclear organelles. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:605–612. doi: 10.1038/nrm1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Berezney R, Coffey DS. Identification of a nuclear protein matrix. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1974;60:1410–1417. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(74)90355-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Capco DG, et al. The nuclear matrix: three-dimensional architecture and protein composition. Cell. 1982;29:847–858. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(82)90446-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nickerson JA, et al. The nuclear matrix revealed by eluting chromatin from a cross-linked nucleus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:4446–4450. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.9.4446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Price CM, Pettijohn DE. Redistribution of the nuclear mitotic apparatus protein (NuMA) during mitosis and nuclear assembly. Properties of purified NuMA protein. Exp Cell Res. 1986;166:295–311. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(86)90478-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Merdes A, Cleveland DW. The role of NuMA in the interphase nucleus. J Cell Sci. 1998;111(Pt 1):71–79. doi: 10.1242/jcs.111.1.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gerace L, Blobel G. Nuclear lamina and the structural organization of the nuclear envelope. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1982;46(Pt 2):967–978. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1982.046.01.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gerace L, et al. Organization and modulation of nuclear lamina structure. J Cell Sci Suppl. 1984;1:137–160. doi: 10.1242/jcs.1984.supplement_1.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Schirmer EC, Foisner R. Proteins that associate with lamins: many faces, many functions. Exp Cell Res. 2007;313:2167–2179. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2007.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wilson KL, et al. Lamins and disease: insights into nuclear infrastructure. Cell. 2001;104:647–650. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Dillon N. The impact of gene location in the nucleus on transcriptional regulation. Dev Cell. 2008;15:182–186. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Harborth J, et al. Self assembly of NuMA: multiarm oligomers as structural units of a nuclear lattice. Embo J. 1999;18:1689–1700. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.6.1689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kempf T, et al. Isolation of human NuMA protein. FEBS Lett. 1994;354:307–310. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)01151-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zeng C, et al. Localization of NuMA protein isoforms in the nuclear matrix of mammalian cells. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 1994;29:167–176. doi: 10.1002/cm.970290208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Boveri T. Die Blastomerenkerne von Ascaris megalocephala und die Theorie der Chromosomenindividualität. Arch. Zellforschung. 1909;3:181–268. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Cremer T, Cremer C. Chromosome territories, nuclear architecture and gene regulation in mammalian cells. Nat Rev Genet. 2001;2:292–301. doi: 10.1038/35066075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lelievre SA, et al. Cell nucleus in context. Crit Rev Eukaryot Gene Expr. 2000;10:13–20. doi: 10.1615/critreveukargeneexpr.v10.i1.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Abad PC, et al. NuMA influences higher order chromatin organization in human mammary epithelium. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18:348–361. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-06-0551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Das AT, et al. Identification and analysis of a matrix-attachment region 5' of the rat glutamate-dehydrogenase-encoding gene. Eur J Biochem. 1993;215:777–785. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb18092.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Harborth J, et al. GAS41, a highly conserved protein in eukaryotic nuclei, binds to NuMA. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:31979–31985. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000994200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Debernardi S, et al. The MLL fusion partner AF10 binds GAS41, a protein that interacts with the human SWI/SNF complex. Blood. 2002;99:275–281. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.1.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Gueth-Hallonet C, et al. Induction of a regular nuclear lattice by overexpression of NuMA. Exp Cell Res. 1998;243:434–452. doi: 10.1006/excr.1998.4178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Misteli T. Beyond the sequence: cellular organization of genome function. Cell. 2007;128:787–800. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Soutoglou E, Misteli T. On the contribution of spatial genome organization to cancerous chromosome translocations. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2008:16–19. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgn017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bystricky K, et al. Chromosome looping in yeast: telomere pairing and coordinated movement reflect anchoring efficiency and territorial organization. J CellBiol. 2005;168:375–387. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200409091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Getzenberg RH, et al. Nuclear structure and the three-dimensional organization of DNA. J Cell Biochem. 1991;47:289–299. doi: 10.1002/jcb.240470402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.King MC, et al. A network of nuclear envelope membrane proteins linking centromeres to microtubules. Cell. 2008;134:427–438. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kim SK. Cell polarity: new PARtners for Cdc42 and Rac. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:E143–145. doi: 10.1038/35019620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Lin D, et al. A mammalian PAR-3-PAR-6 complex implicated in Cdc42/Rac1 and aPKC signalling and cell polarity. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:540–547. doi: 10.1038/35019582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Tall GG, Gilman AG. Purification and functional analysis of Ric-8A: a guanine nucleotide exchange factor for G-protein alpha subunits. Methods Enzymol. 2004;390:377–388. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(04)90023-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Tall GG, Gilman AG. Resistance to inhibitors of cholinesterase 8A catalyzes release of Galphai-GTP and nuclear mitotic apparatus protein (NuMA) from NuMA/LGN/Galphai-GDP complexes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:16584–16589. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508306102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kardon JR, Vale RD. Regulators of the cytoplasmic dynein motor. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:854–865. doi: 10.1038/nrm2804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]